By Charles W. Keysor, Founding editor of Good News

The Risk of Renewal

By Riley B. Case-

When Charles Keysor wrote his article “Methodism’s Silent Minority” in the Christian Advocate in 1966, an article that basically launched the Good News movement, he spoke about numbers of Methodists who affirmed historic Methodism and were faithful and active in their local churches but were basically unrecognized and unappreciated in the larger councils of the church. Keysor referred to these orthodox believers as a “silent minority.” He suggested their numbers were larger than what church leaders had usually assumed.

Keysor’s analysis at the time was in contrast to liberal observers who insisted that “fundamentalism” (a pejorative label used to refer to all evangelicals) was a dying ideology with no future in the Methodist Church, or anywhere else for that matter. Keysor quoted his own professor at Garrett Seminary, Paul Hessert, who foresaw a continued eclipse of orthodox influence within the seminary-trained Methodist ministry, but who believed that such a perspective might continue among supply pastors and pockets of lay people.

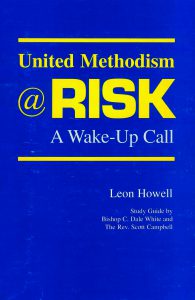

Surprise! Something happened on the way to extinction. According to the 2003 book, United Methodism @ Risk: A Wake-Up Call, produced by a group called Information Project for United Methodists, and introduced with great fanfare to the press and to the Council of Bishops, Methodism is in danger of being “taken over” by this very “silent minority” Keysor spoke about.

In what appears to be a near-state of panic, The Information Project charges that “powerful,” “well-organized and funded” conservative renewal groups (the book refuses to refer to them as “evangelicals”) would take the church to a place where “diversity and tolerance and breadth of spirit are in short supply.” The “progressive” bishops, seminary professors, and board and agency staff people who dominate the Information Project characterize the renewal groups as those who “look backwards to times when knowledge was feared, questioning was suppressed, and imagination was squelched.”

The book is a call to action. It argues that the renewal groups and the point of view they represent are to be unmasked and resisted, presumably so that United Methodism can be kept pure for “diversity and tolerance.” Tolerance, in this case, is translated to mean anything that counters the traditional orthodox vision for Christian theology, marriage, and sexuality.

One reads United Methodism @ Risk with sadness. How is it that evangelicals have been so long in the UM Church and yet are so clearly misrepresented and misunderstood? How did evangelicals go from being people whose faith was criticized at one time for being “privatistic,” and “individualistic,” to persons who are really motivated by a certain social and political agenda? When did evangelicals move from being people who simply wanted to be left alone to do ministry in a United Methodist tradition, to being persons who are power hungry and want to take over the church?

The book is an attack on evangelical renewal groups — but it is more. It is an attack on the Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church and upon many of the most loyal of the church’s members. The alarm is sounded not against people in power who oversaw the monumental decline of membership within the last several decades, but upon the people who believe that the people who are in power (bishops, seminaries, and boards and agencies) are not serving them well.

Consider the typical renewal group supporter: here is a couple in their sixties who have been loyal United Methodist all their lives. They have held most of the church offices; they have taught Sunday school; they have tithed. They have lived through a succession of pastors, some good, and some, while sincere, who didn’t believe much. They have agonized over Sunday school material that they didn’t understand. They have wondered why their local church struggles while the nearby Baptist church thrives.

Our United Methodist couple is finding that a lot of their spiritual nurture is coming not from their church but from a neighborhood Bible study. They struggle on how to answer their friends who show them newspaper clippings of a United Methodist bishop who publicly scorns the church’s affirmation that Christ did truly rise from the dead.

Our couple’s own children, away from home, are not affiliating with a United Methodist church. One daughter, who claims she never heard the gospel in her home church, was converted in college through Inter-Varsity, and is active in an independent church. A son, after marriage, attended a United Methodist church in the city until he and his wife were attracted to a Nazarene church with an active children’s program.

The wife of our couple has been active in United Methodist Women, and enjoys the company of other women in the group, but finds the programs boring. The man has sat through numbers of charge conferences where a district superintendent talks grandly about “the connection” and the importance of paying apportionments. On Mission Emphasis week the “missionary” who speaks at their church is really a person who did a two-week volunteer mission trip to work on a church parsonage in another state. There was no mention of Jesus in the presentation.

Our couple has identified with Good News or the Confessing Movement or Aldersgate Renewal Ministries because they are offer a message of hope. They understand that each ministry is working for change in its own unique way. Our couple may not understand everything implied in the words “doctrinal integrity” but they are aware of the difference between preachers who preach on the necessity of being born again, and those who offer vague homilies on “hope” or “love.” They respond to a Mission Society missionary [now TMS Global] who is working on new church starts in Bolivia.

This couple, however, along with 90 percent of all other United Methodists, would fall in the category of what Bishop Joseph Sprague has labeled “Christo-centric exclusivism that ipso facto prepares the soil of stiff-necked, exclusivistic arrogance.” The people who support the evangelical renewals groups are not “extremists,” nor could they be considered “right-wing,” if one were to understand these words in the context of the whole of Protestantism in America (and around the world, for that matter).

A profile of the supporters of the several evangelical renewal groups shows them to be among the most loyal and faithful United Methodists in their local churches. They pay their apportionments and pray for their bishops. Many claim if it were not for one or several of the renewal groups they would no longer be United Methodist. Neither they, nor the groups they support, wish to “take over” the denomination for a very simple reason. They understand the essence of the denomination to be the local church, not the seminaries, nor the boards and agencies, nor the episcopacy. They also understand that the purpose of the church is to save souls and nurture disciples, not to make public declarations about government public policy.

This is not to say, however, that renewal group supporters, and perhaps the vast majority of United Methodists, are content that their own convictions are often undermined by the seminaries, their own understandings of the Bible’s view on celibacy and faithfulness are continually being challenged, and that their “leaders” claim to represent them while denouncing a fellow United Methodist who is President of the United States.

United Methodism is indeed at risk. It is in the midst of a 100-year decline. According to Roger Finke and Rodney Stark, in their book, Acts  of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion (University of California Press, 2000) the number of Methodist adherents in America has decreased from 84 of every 1,000 Americans in 1890 to 36 in 1990. The years of the decline correspond exactly to the years that liberalism and institutionalism have dominated Methodism.

of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion (University of California Press, 2000) the number of Methodist adherents in America has decreased from 84 of every 1,000 Americans in 1890 to 36 in 1990. The years of the decline correspond exactly to the years that liberalism and institutionalism have dominated Methodism.

From 1970 to 2003, membership of the United Methodist Women has declined by 54 percent. One would think, whether liberal or evangelical, that such statistics would call for some sort of reform, or at least some self-examination. Something clearly in not going well. Yet when the renewal groups call for reform of the Women’s Division it is absurdly interpreted as an attack on women. Women’s ministries are alive and well in numbers of churches, but are criticized as being “unofficial” because they do not have the blessing of the Women’s Division (United Methodist Women).

In their sociological analysis Stark and Finke distinguish between “low tension” and “high tension” churches. Low tension churches, where few demands are made (read “tolerance,” “diversity,” and “breadth of spirit”) are becoming increasingly irrelevant and are dying in America. High tension churches, with an emphasis on moral and doctrinal values, are growing. Stark and Finke argue that it seems impossible that once a group becomes low tension and starts down the road to decline, it can ever be reclaimed. There may be an exception, however, in United Methodism. If there is it will be because of groups like Good News and the Confessing Movement. They have done studies in several conferences to substantiate statistically what many of us already know instinctively, namely, that liberal churches are dying and evangelical churches are growing.

Stark and Finke are doing sociological work in a secular setting. If the Information Project really wants “dialogue” perhaps a discussion of the Stark and Finke book would be a good place to begin.

Riley B. Case is the author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon). He is a retired United Methodist clergy person from the Indiana Annual Conference, the associate director of the Confessing Movement, and a lifetime member of the Good News Board of Directors. This adapted essay originally appeared in the September/ October 2003 issue of Good News.

0 Comments