By Faith McDonnell-

By Faith McDonnell-

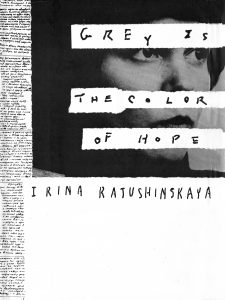

In 1989, People magazine reviewed Ratushinskaya’s prison memoir, Grey is the Color of Hope. The review recounted how the then-exiled-in-the-West poet had been arrested in 1983 at the age of 29 and sentenced to seven years’ hard labor for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, possession of human rights documents, possession of articles about the Polish labor movement, and possession of anti-Soviet literature,” among other things.

A New York Times review of the book describes Ratushinskaya’s companions in the labor camp’s “Small Zone,” a restricted area for “particularly dangerous female political criminals.” According to the Times: “All of them were defiant nonconformists who chose imprisonment rather than renege on their political or religious principles. They included a leading activist of the Helsinki Watch committee, a recent convert to Roman Catholicism who received a 10-year term for helping an underground priest teach a children’s catechism class, a Pentecostal Christian and the editor of an underground, samizdat, journal dedicated to feminist issues such as the horrors of Soviet maternity wards…”

It is quite probable that the beatings, torture, vitamin-deficient diet, and extreme conditions under which Ratushinskaya spent four years contributed to the cancer that brought about her death. In his obituary of Irina Ratushinskaya for The Guardian, the Rev. Michael Bourdeaux puzzles, “precisely why she was singled out for such inhuman treatment remains a mystery.” He continues, “One might have expected that she would have been given an intimidating rebuke by the KGB and dismissed from her job. Instead she found herself confronting the full force of the Soviet law, but poetry in Russia was always dangerous.” Bourdeaux would know. He founded the British-based Keston College that for years provided information on prisoners of faith and conscience in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, including Ratushinskaya.

The People article reveals that 250 poems by this courageous dissident – who graduated in physics from Odessa University in 1976 and became a teacher – were written via a matchstick and a bar of soap. Her poems were smuggled out of the Small Zone by her husband, physicist and human rights activist, Igor Gerashchenko. He risked his own freedom to ensure that Ratushinskaya’s voice was heard by passing the poems on to Western journalists. Because of this initiative two books of her poetry were published in the United States while she was still in prison. And it was obvious from her poems that Ratushinskaya was freer as a labor camp prisoner than her jailers could ever be.

Her poem to which I refer most often when I am writing or speaking about the global persecution of Christians is entitled “Believe Me.” She wrote it the day after she was freed from the labor camp. It is a poem I use to inspire myself and others to pray for those who are persecuted for their faith. The poet’s early release came as part of the negotiations for the summit between Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik, on October 9, 1986. The next day she wrote this:

“Believe me, it was often thus

In solitary cells, on winter nights

A sudden sense of joy and warmth

And a resounding note of love.

And then, unsleeping, I would know

A-huddle by an icy wall:

Someone is thinking of me now,

Petitioning the Lord for me.

My dear ones, thank you all

Who did not falter, who believed in us!

In the most fearful prison hour

We probably would not have passed

Through everything – from end to end,

Our heads held high, unbowed –

Without your valiant hearts

to light our path.”

– “Believe me,” Irina Ratushinskaya, Kiev, October 10, 1986.

It must have seemed strange to write again in freedom, to write from a distance about the freezing cold solitary isolation cell known as SHIZO with which she had been so intimately acquainted. Ratushinskaya had been subjected to this torture on a regular basis for refusing to renounce her Christian faith, refusing to inform on fellow prisoners, and for refusing to say she would never write poetry again. Years later she still suffered from excruciating headaches because of a concussion she received when a brutal guard threw her headfirst against a wooden trestle in the cell.

On her first day waking up in freedom, Ratushinskaya was eager to put pen to paper. And she used the occasion to write a tribute to her intercessors. The former prisoner revealed how she felt tangibly the effect of their prayers: in a “sudden sense of joy and warmth and a resounding note of love” while “a-huddle by an icy wall.” Her words described the experience of many Christian prisoners of faith and the supernatural warmth they felt while in conditions that had no business feeling warm. The result of, as Ratushinskaya put it, “someone thinking of me now, petitioning the Lord for me.” A mystery, certainly, but undeniable when coming from the person who experienced this miracle, and especially from someone who frequently had been in trouble for speaking truth.

Ratushinskaya spoke of the “valiant hearts” that lit the path for those in the “most fearful prison hour.” Members of Congress – such as the human rights heroes Frank Wolf, Chris Smith, and Tom Lantos – did their part as advocates for the poet. People around the world became prayer warriors.

I first stumbled upon one of those valiant hearts, the Rev. Dr. Dick Rodgers, an Anglican priest and orthopedic surgeon, when I was wandering through England’s cathedrals in the summer of 1985. Rodgers was distributing leaflets about the poet. In 1986 Rodgers spent all of Lent inside a cage at St. Martin in the Bull Ring Anglican Church in Birmingham that functioned as a replica of Ratushinskaya’s prison cell.

Rodgers shaved his head the way that her head had been shaved and ate prison-style rations, to call attention to Ratushinskaya’s malnutrition-inducing prison diet of hard bread and rotted-fish broth. For an age in which there was barely any electronic communication, let alone social media, Rodgers brought the cause of this Christian dissident to the global community. Bourdeaux writes in his obituary for Ratushinskaya that “Irina came to believe that the huge publicity [Rodgers] engendered contributed to saving her life.”

Bourdeaux relates how on the morning of October 10, 1986, the news that Irina Ratushinskaya was free “upstaged the event for which the media had been waiting — the opening of the Reykjavik summit between U.S. president Ronald Reagan and the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.” He explains that Gorbachev wanted the world to know that he was serious about improving both international and domestic relations. He wanted to show the improvement in human rights brought about by perestroika (reconstruction).

Two months after Ratushinskaya’s release, she and Gerashchenko were allowed to leave the Soviet Union for medical treatment. While they were away they were stripped of Soviet citizenship and so settled in London. Ratushinskaya was also Poet in Residence at Northwestern University from 1987-1989. But after a few years of celebrity and popularity for Ratushinskaya, the West — not learning anything from the example of the Soviet Union — lost interest in the heroism of dissidents from the Soviet Union. In 1993, she and Gerashchenko had twin sons, Sergei and Oleg, and the family returned to Russia in 1998.

were away they were stripped of Soviet citizenship and so settled in London. Ratushinskaya was also Poet in Residence at Northwestern University from 1987-1989. But after a few years of celebrity and popularity for Ratushinskaya, the West — not learning anything from the example of the Soviet Union — lost interest in the heroism of dissidents from the Soviet Union. In 1993, she and Gerashchenko had twin sons, Sergei and Oleg, and the family returned to Russia in 1998.

In “Believe Me,” Ratushinskaya thanked those who remembered her, “who did not falter, who believed in us.” But it was she who did not falter. To quote her, she “passed through everything — from end to end” with her head “held high, unbowed.” Finally, she passed through suffering the tolls of cancer on a body that had already been tested by the harsh reality of Strict Regime Labor Camp No. 3. She left her beloved Igor once more, as she did when she was wrenched from him in the Kiev Courtroom and he called out, “Hold steady, darling, I love you!” to support her through the long years of separation.

Now Ratushinskaya is gone once more. We often speak glibly of those who have died “receiving their reward in heaven,” but Irina Ratushinskaya has a Hebrews 11 reward. “Some faced jeers and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment … the world was not worthy of them.” Irina and other valiant warriors of the era of Soviet persecution lit the path for me that brought me where I am today. And now, in the true freedom of Eternal Life, the poet is part of the great cloud of witnesses cheering on those of us still running our race.

Faith McDonnell is the Director of Religious Liberty Programs and of the Church Alliance for a New Sudan at the Institute on Religion and Democracy in Washington, D.C. Reprinted by permission. Editor’s note: On March 26, 1987, the Institute on Religion and Democracy presented its third Religious Freedom Award to Irina Ratushinskaya. At the reception, then Secretary of State George P. Shultz said of Irina, “In her dogged determination to live her own life and speak her own mind, regardless of the personal cost, she has taught others the meaning of human freedom.”

0 Comments