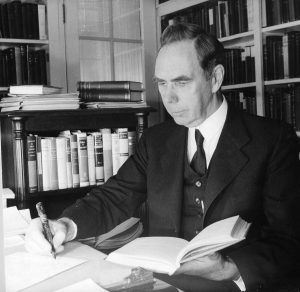

Dr. Edwin Lewis. Photo courtesy of Drew University.

By James V. Heidinger II-

Debate has been renewed in recent months about the role of doctrine for United Methodists. What is the place, for example, of orthodox Christian doctrine in our church? For years we have heard that we are not a creedal church; that Methodists have been more interested in “faith working through love”; that Methodists have always been more experiential than doctrinal; that doctrine should not be the basis for juridical action or for coercion.

There is truth in some of this, no doubt. In 1952, the bishops of The Methodist Church said in addressing that year’s General Conference that “Our theology has never been a closely organized doctrinal system. We have never insisted on uniformity of thought or statement.” However, the bishops went on to say in that address, “There are great Christian doctrines which we most surely hold and firmly believe.” Commenting on this address, Bishop Nolan B. Harmon said, “Methodists have always heatedly rejected the idea that Methodism is simply a ‘movement’ with no formal doctrine” (Understanding the United Methodist Church, Abingdon, 1974).

The oral tradition claiming Methodism to be a non-creedal church has a history that reaches back at least to the early 1900s, the time of the fundamentalist/modernist controversy. Methodism at that time had just experienced the unpleasant controversy about its holiness message. General Conference took action in 1894 to bring holiness evangelists under the church’s strict control. Many left Methodism to form no less than ten different holiness groups. They believed the Methodist Church was not being faithful to Wesley’s understanding of sanctification and perfect love.

In the face of the bitter controversy beginning to brew over the fundamentalist/modernist debate, Methodism was determined to avoid more division. The result was that Methodism moved even further away from careful creedal and doctrinal formulation to a mood of greater openness, tolerance, and emphasis on Christian love in action. There was also the feeling that with so many urgent social ills in America’s growing cities, theological debate might prevent the church from meeting human needs.

This led to a growing antipathy toward creeds, a pattern that can be seen in the periodical literature of 1910-1920. The trend clearly was to shift focus from creeds to human needs. A.H. Goodenough wrote in the Methodist Review in November, 1910: “Creeds have had their day. They are no longer effective. Without doubt, they were well intended. Possibly they have done some good—they certainly have done much harm. The church has been loyal to her creeds, and has spent much good blood and splendid brains in the defense of them. All this was considered the very essence of Christianity. It was child’s play, as we now see it, and in some instances paganism.… The creeds are retired to the museums and labeled ‘Obsolete.’”

Seeing division and strife around them from the fundamentalist/modernist controversy, Methodists were more than ready to relax their attention on creedal and doctrinal formulation. One New York pastor, Philip Frick, wrote with near exhilaration an article entitled, “Why the Methodist Church Is So Little Disturbed by the Fundamentalist Controversy,” (Methodist Review, 1924), in which he gives the reason as being Methodism’s lack of dogmatic creedal assertion.

Further evidence of the growing antipathy to creedal formulation at this time can be seen in the change in requirements for membership. In 1864, the Methodist Episcopal Church required members to subscribe to the Articles of Religion. This requirement was removed in 1916. Belief in the Apostles’ Creed continued to be required after 1924 as it was included in the baptismal ritual, but it, too, was dropped in 1932.

It may well have been in response to General Conference’s dropping of the Apostles’ Creed in 1932, as well as the popular preference for using the new Social Creed rather than theological creeds, that led to Edwin Lewis’ article of alarm over “The Fatal Apostasy of the Modern Church.” Lewis, a professor of systematic theology at Drew Theological Seminary, wrote stinging words in response to these changes: “But what does the modern church believe? The church is becoming creedless as rapidly as the innovators can have their way. The ‘Confession of Faith’ — what is happening to it? Or what about the ‘new’ confessions that one sees and hears — suitable enough, one imagines, for, say, a fraternal order. And as for the Apostles’ Creed — ‘our people will not say it any more’: which means, apparently, that ‘our people, having some difficulties over the Virgin Birth and the resurrection of the body, have elected the easy way of believing in nothing at all — certainly not in “the Holy Catholic Church”.’” (Religion in Life, Autumn, 1933).

So this era saw a transition from doctrinal and theological concerns to a growing new interest in, if not preoccupation with, social ministry.

John Wesley.

The church focused not on the content of belief, for that could be divisive, but rather upon Christian love in action through social ministry. This inattention to theology may have been partially responsible for Methodism’s tragic susceptibility to the influence of liberal theology and German philosophy that were rapidly finding a home in our Methodist seminaries.

The move away from doctrine during this period also provided natural cover for pastors who were being trained in the emerging liberal theology. Many could surrender the supernatural elements of apostolic faith — the Virgin Birth, the deity and miracles of Jesus, and his bodily resurrection — and continue on in ministry without ever having to talk much about those things. Social ministry was in, theological definition was out.

This helps us understand the oral tradition that has come down to us today. It is this: United Methodism is not a creedal church, we live in a changing world, and doctrines we used to teach may not be relevant today. And most recently, folks in one annual conference were warned by letter of a “movement away from an evolving and ever-changing understanding of God guided by the Holy Spirit.” Of course, “an evolving and ever-changing understanding of God” could never be expressed in a creed or traditional formulation, for it would be forever changing. The best folks might get would be a list of “Affirmations of the month,” but not “the faith once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3).

Looking again at our Wesleyan tradition

But is the oral tradition really our Wesleyan theological tradition? One senses we have done violence to both Wesley and American Methodism with such sloppiness and ambiguity.

Charles Yrigoyen, Jr., in his helpful book, Belief Matters (Abingdon, 2001), reminds us that the church’s doctrine helps us understand the biblical message in a “clearer, holistic, more organized way,” and thus we can communicate it more effectively. Unfortunately, many United Methodists today don’t really understand that message. He also reminds us that the official doctrine of the church “protects us from false and subversive teachings.” Pastors have the responsibility to feed their flocks and make sure they are not grazing in toxic pastures.

Belief certainly mattered to John Wesley, despite the claims of the revisionists. Wesley insisted on doctrinal faithfulness. In 1763 Wesley drafted a Model Deed which stipulated that the pulpits of the Methodist chapels were to be used by those persons who preached only those doctrines contained in Wesley’s New Testament notes and his four volumes of sermons. If a preacher didn’t conform, he was out within three months. Wesley would never have shrugged off reports of an errant preacher by saying, as do many today, “Well, we Methodists think and let think.” (He did say that, of course, in “The Character of a Methodist,” but let’s quote his entire sentence: “But as to all opinions which do not strike at the root of Christianity, we think and let think.”)

While Wesley had a refreshing breadth of spirit about him, there were doctrines he viewed as essential to the faith. Robert Chiles, concurring with Methodist theologian Colin Williams, lists the doctrines that Wesley insisted on at various times in his ministry as “original sin, the deity of Christ, the atonement, justification by faith alone, the work of the Holy Spirit (including new birth and holiness) and the Trinity” (Chiles citing Colin Williams, John Wesley’s Theology Today). This is simply apostolic Christianity.

Yes, we United Methodists take doctrine very seriously. Each person seeking to become a clergy member within our denomination is asked, “(8) Have you studied the doctrines of The United Methodist Church? (9) After full examination, do you believe that our doctrines are in harmony with the Holy Scriptures? (10) Will you preach and maintain them?” (Book of Discipline, Par. 327). Candidates are expected to answer in the affirmative.

The church, in fact, takes doctrine seriously enough that a bishop, clergy member, local pastor, or diaconal minister may be charged formally with “dissemination of doctrines contrary to the established standards of doctrine of The United Methodist Church” (Discipline, Par. 2624.1f), which can lead to a trial. Doctrine is not tangential to the people called Methodists.

Alister McGrath, professor at Oxford, has warned that “Inattention to doctrine robs a church of her reason for existence, and opens the way to enslavement and oppression by the world.” Certainly, attention to doctrine will help United Methodists understand that our doctrinal standards are not, have never been, and must never be, “evolving and ever-changing.” That would be a guarantor of continued confusion and further decline.

James V. Heidinger II is the publisher and president emeritus of Good News. A clergy member of the East Ohio Annual Conference, he led Good News for 28 years until his retirement in 2009. Dr. Heidinger is the author of several books, including the recently published The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism (Seedbed). This essay originally appeared in the September/October 2003 issue of Good News.

The church does not take doctrine seriously. If it did, bishop Joseph Sprague would have been tried for heresy, defrocked and excommunicated for his public comments at Iliff denying the virgin birth and the bodily resurrection of Christ. And he is by no means alone in disregarding the basic tenets of orthodox Christian faith. Your description of the modern UMC and the majority of her clergy fits well with what I experienced in the Virginia Annual Conference during my three decades of membership. If I still belonged to a UMC I would emulate NFL players and take a knee in the church aisle the next time the UMC Social Creed was used instead of the Apostles or Nicene (which was distressingly frequent as I remember).

An ever-evolving and changing God might very well change his mind about me or, furthermore, all of humanity. This creedless evolution is a religious belief, but it isn’t Methodist, and it isn’t Christian. It is heresy. Most concerning is the question of authority of a people that hold to almost no unified creed, especially not a scriptural one. If we say and agree we should all love one another and help the poor and suffering, by who’s definition of “love” do we serve? What if “help the suffering” was newly “revealed” to the promoted enlightened ones to mean we should put the suffering out of their misery? Isn’t acceptance of “special, unbiblical revealation” a historically proven recipe and excuse for genocide?

Am I able to make certain claims about God? Yes, because my claims are not just my own, but have stood for nearly two-thousand years; tested, proven, and recorded by the saints that dedicated and, at times, gave their very lives, that we might know the truth. Thier creed is my creed. Our instruction comes from the Lord. I know his His ways because of his Word, all 66 books, of which becomes clearer, and yet remains ever-consistent and unchanging, as I walk in His precepts. This is Methodism—that we hold one another accountable and anchor one another to the Word of God, that we may be The Church, the hands and feet of Christ, and a beacon to a dying world. If we abandon the truth, all our good deeds are for nothing, as we can only feed and clothe the suffering, as we, the dying, lead others also to death.