by Steve | Mar 17, 2021 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Steve Beard –

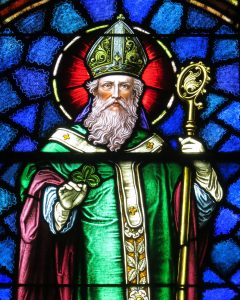

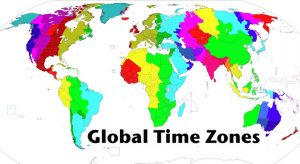

Photo: Saint Patrick Catholic Church (Junction City, Ohio) – stained glass, Saint Patrick

While sifting through obscure Spanish colonial records, it was discovered a few years ago that the very first St. Patrick’s Day parade was not conducted in Boston, Chicago, nor New York City.

Instead, the Irish feast day was celebrated in modern day St. Augustine, Florida, in 1601.

“They processed through the streets of St. Augustine, and the cannon fired from the fort,” said Prof. J. Michael Francis of the University of South Florida at St. Petersburg, who discovered the document. The ancient records named “San Patricio” as “the protector” of the area’s maize fields. “So here you have this Irish saint who becomes the patron protector of a New World crop, corn, in a Spanish garrison settlement,” he said.

This strange twist in the story and celebration of St. Patrick, a fifth century holy man, is really not that surprising. Historians are constantly attempting to set the record straight. After all, Patrick was not Irish (born in Britain of a Romanized family). He was never canonized as a saint by the Catholic Church. Interestingly, there are two St. Patrick’s Cathedrals in Armagh, Ireland – one Catholic and one Protestant. Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin is part of the Church of Ireland – with both Catholic and Protestant clergy.

The legacy of Ireland’s patron saint blurs a lot of lines – but, he is notably worth celebrating.

Patrick was brutally abducted at the age of 16 by pirates and sold as a slave in Ireland. For six agonizing years in a foreign land, he largely lived in abject solitude attending animals. The Christian faith of his family that he found unappealing as a teenager became his spiritual lifeline to sanity and survival while in captivity.

“Tending flocks was my daily work, and I would pray constantly during the daylight hours,” he writes in his Confession – one of only two brief documents authentically from Patrick’s own hand. “The love of God and the fear of him surrounded me more and more – and faith grew and the Spirit was roused, so that in one day I would say as many as a hundred prayers and after dark nearly as many again even while I remained in the woods or on the mountain. I would wake and pray before daybreak – through snow, frost, rain – nor was there any sluggishness in me (such as I experience nowadays) because then the Spirit within me was ardent.”

Through a divine dream, Patrick was inspired to make his escape. His journey as a fugitive was, according to his testimony, a 200 mile trek to the coast. Further miraculous circumstances allowed him to wrangle himself aboard a ship to escape his imprisonment in Ireland. He finally made it back to the loving embrace of his family.

Years later, however, another mystical dream launched his trajectory into the ministry and, ultimately, back to Ireland. “We appeal to you, holy servant boy,” said the voice in the dream, “to come and walk among us.”

For many years, he trained to become a priest. Eventually, in 432 A.D., Patrick returned to the shores of the land where he once was held captive.

“Believe me, I didn’t go to Ireland willingly that first time [when he was taken as a slave] – I almost died there,” he wrote in his Confession. “But it turned out to be good for me in the end, because God used the time to shape and mold me into something better. He made me into what I am now – someone very different from what I once was, someone who can care for others and work to help them. Before I was a slave, I didn’t even care about myself.”

Noted classics scholar Philip Freeman, author of St Patrick of Ireland, points out the distinguished uniqueness of Patrick’s public vulnerability – a trait that was not characteristic of a man of his stature and notoriety. As an elderly and well-known bishop, Patrick begins his Confession with these words: “I am Patrick – a sinner – the most unsophisticated and unworthy among all the faithful of God. Indeed, to many, I am the most despised.”

“The two letters are in fact the earliest surviving documents written in Ireland and provide us with glimpses of a world full of petty kings, pagan gods, quarreling bishops, brutal slavery, beautiful virgins, and ever-threatening violence,” writes Freeman. “But more than anything else, they allow us to look inside the mind and soul of a remarkable man living in a world that was both falling apart and at the dawn of a new age. There are simply no other documents from ancient times that give us such a clear and heartfelt view of a person’s thoughts and feelings. These are, above all else, letters of hope in a trying and uncertain time.”

While there are many beautiful, miraculous, and fantastical stories about St. Patrick, his Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus – the other document authentically written by Patrick – exposes his heart and soul. It portrays the character of a man worthy of emulation and celebration. His humility, empathy, and righteous indignation scorches the letter as he takes up the cause of the voiceless captives and powerless victims of slavery – a common practice in the fifth century.

The fiery correspondence addresses the horrific news that a group of newly baptized converts were killed or taken into slavery on their way home by a petty British king named Coroticus, known to be at least nominally a Christian.

“Blood, blood, blood! Your hands drip with the blood of the innocent Christians you have murdered – the very Christians I nourished and brought to God,” Patrick writes. “My newly baptized converts, still in their white robes, the sweet smell of the anointing oil still on their foreheads – you murdered them, cut them down with your swords!”

Violating cultural and ecclesiastical protocols, the letter was sent broadly and caused a stir. Courageously, Patrick launched a public ruckus – outside his governance – over the “hideous, unspeakable crimes” because he believed that God truly loved the Irish – even if church leaders elsewhere did not. Patrick’s vision for the love of God was expansively generous. “I am a stranger and an exile living among barbarians and pagans, because God cares for them,” he writes (emphasis added).

“Was it my idea to feel God’s love for the Irish and to work for their good?” Patrick writes. “These people enslaved me and devastated my father’s household! I am of noble birth – the son of a Roman decurion – but I sold my nobility. I’m not ashamed of it and I don’t regret it because I did it to help others. Now I am a slave of Christ to a foreign people – but this time for the unspeakable glory of eternal life in Christ Jesus our master.”

Having been captive, he does not write about slavery whimsically. He was an outspoken voice opposing slavery at a time when it was simply considered commonplace. Furthermore, he was a fierce advocate for those who were most vulnerable and abused in captivity.

“But it is the women kept in slavery who suffer the most – and who keep their spirits up despite the menacing and terrorizing they must endure,” he writes in his Confession. “The Lord gives grace to his many handmaids; and though they are forbidden to do so, they follow him with backbone.”

When Patrick heard about the bloody attack and abductions after the baptism service, he sought to reason with Coroticus: “The very next day I sent a message to you with a priest l had taught from childhood and some other clergy asking that you return the surviving captives with at least some of their goods – but you only laughed.”

In response, Patrick derides Coroticus and his men as “dogs and sorcerers and murderers, and liars and false swearers … who distribute baptized girls for a price, and that for the sake of a miserable temporal kingdom which truly passes away in a moment like a cloud or smoke that is scattered by the wind.”

In order to make his point, he prays: “God, I know these horrible actions break your heart – even those dwelling in Hell would blush in shame.”

With pastoral care, Patrick addresses the memory of those killed after their baptism: “And those of my children who were murdered – I weep for you, I weep for you … I can see you now starting on your journey to that place where there is no more sorrow or death. … You will rule with the apostles, prophets, and martyrs in an eternal kingdom.”

Even in an inferno of justifiable rage, Patrick extends an olive branch of redemption: “Perhaps then, even though late, they will repent of all the evil they have done – these murderers of God’s family – and free the Christians they have enslaved. Perhaps then they will deserve to be redeemed and live with God now and forever.”

“The greatness of Patrick is beyond dispute: the first human being in the history of the world to speak out unequivocally against slavery,” writes historian Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization. “Nor will any voice as strong as his be heard again till the seventeenth century.”

All around the globe, March 17 is set aside to honor a great man who overcame fear with faith, overcame hate with love, and overcame prejudice with hope. Although he had every reason in the world to resist the dream to return to “walk among” the Irish, Patrick responded to the God-given impulse of his heart – even when it was most difficult. He knew the dangers and challenges and returned anyway.

Patrick offered himself as a living example of what new life could look like for the Irish. “It is possible to be brave – to expect ‘every day … to be murdered, betrayed, enslaved – whatever may come my way’ – and yet be a man of peace and at peace, a man without sword or desire to harm, a man in whom the sharp fear of death has been smoothed away,” writes Cahill of Patrick. “He was ‘not afraid of any of these things, because of the promises of heaven; for I have put myself in the hands of God Almighty.’ Patrick’s peace was no sham: it issued from his person like a fragrance.”

Happy St. Patrick’s Day.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Steve | Mar 12, 2021 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

The Book of Discipline. A UMNS photo by Mike DuBose.

By Thomas Lambrecht –

There are two proposals that would change United Methodism by creating different regional versions in the various geographical areas of the church: Africa, Europe, the Philippines, and the U.S. One proposal is from the Connectional Table and the other is from a group of delegates from outside the U.S. called the Christmas Covenant.

I have written about the Christmas Covenant before in more detail. At present, the Christmas Covenant seems to be the version of regionalization most preferred by church leaders. It sets up the UM Church in the U.S. as its own regional conference and creates regional conferences in Africa, Europe, and the Philippines. Each regional conference (including in the U.S.) would have the ability to change any part of the denomination’s Book of Discipline that it wants to change, except for items that the church Constitution protects or items that are protected by a two-thirds vote of the General Conference.

There could be different standards for clergy in each regional conference, different requirements to which clergy and bishops would be held accountable, different methods of local church organization, and different criteria for church membership, to give just a few examples. Each regional conference would create a different version of United Methodism for that geographical area. Regional conferences could even give annual conferences the ability to create different standards and requirements, as well.

Proponents of regionalization say that the reason for this proposal is to allow United Methodism to adapt to the different ministry contexts found in each geographical area of the world. They say that a one-size-fits-all version of Methodism does not work. In addition, proponents state that central conference delegates are tired of dealing with reams of petitions at General Conference that pertain only to United Methodists in the U.S. They want to focus on global matters at General Conference and allow each region to work independently on matters germane to that region.

Importantly, some proponents insist that regionalization is not an attempt to resolve the church’s conflict over human sexuality, marriage, and ordination. Some contend that regionalization can be adopted along with the Protocol for Separation to resolve our conflict.

However, some proponents and other church leaders have seized on the idea that, if regionalization is adopted, separation would no longer be necessary, since each region in the church could adopt its own standards regarding sexuality, marriage, and ordination. Such an understanding fails to take into account the real dimensions of our church conflict.

Regionalization for the U.S.

First, it is important to understand that regionalization proposals would primarily benefit United Methodists in the U.S. Those in the central conferences outside the U.S. already have the power to change and adapt the provisions of the Book of Discipline to fit their ministry and legal context. The 2016 General Conference even moved in the direction of expanding that ability to adapt the Discipline. In light of the crisis point in our conflict, that expansion was put on hold but could easily be taken up again in the future.

U.S. United Methodists were not originally given the power to adapt provisions of the Discipline for two reasons. First, U.S. delegates were always in the overwhelming majority and still make up about 55 percent of the delegates. Second, there is no one unified U.S. conference, as the country is divided up into five jurisdictions. Giving each jurisdiction the authority to adapt the Discipline was seen as a bridge too far, creating too much diversity within one country. Besides, U.S. delegates were essentially writing the Discipline for their context, while giving non-U.S. United Methodists the ability to change what did not work in their settings. Giving the U.S. church the ability to adapt was unnecessary.

But things have changed and are changing. The U.S. percentage of the General Conference is at its lowest point ever. As Methodism in the U.S. continues to decline dramatically and Methodism in Africa continues to grow significantly, within eight to twelve years, U.S. delegates could be in the minority.

On top of that, the two-thirds of U.S. delegates that are centrists or progressives are being outvoted by the one-third of U.S. delegates that are traditionalists, along with traditionalists in Africa, Eurasia, and the Philippines. If the U.S. voted separately from the rest of the church, the centrists and progressives would overwhelmingly control the direction of the church in the U.S. But the voices of delegates outside the U.S., along with U.S. traditionalists, are setting the agenda for the global church. U.S. centrists and progressives disagree with that traditionalist agenda and can use regionalization to resist it.

Regionalization’s Impact on Marriage and Ordination

If the U.S. church is given the power to adapt the Discipline that the central conferences currently have, and if that power is expanded to cover more parts of the Discipline (as the Christmas Covenant envisions), the situation would change dramatically. The global definition of marriage as between one man and one woman could be changed to allow for same-sex marriage in the U.S. church. The global requirement that all clergy should be celibate in singleness or faithful in a heterosexual marriage could be changed to delete the word “heterosexual,” or the requirement for celibacy and faithfulness could be struck out altogether in the U.S. (as at least one petition to the 2020 General Conference proposes). The provision barring clergy from performing same-sex weddings could be removed in the U.S. The chargeable offenses holding clergy accountable on these matters could be scrapped in the U.S.

While some proponents of regionalization may see it primarily as a way to free General Conference from having to deal with matters strictly pertaining to the U.S., it would also allow the U.S. church to shift in a much more progressive direction. This progressive shift would affect not only the U.S. church’s teachings and standards on marriage and ordination; it would also affect how the church’s doctrinal standards are interpreted and what social or political statements the U.S. church would make on matters of public interest. One could expect the U.S. church to espouse more progressive politics than it currently does.

Regionalization vs. Separation

Traditionalists would not object to this kind of regionalization for the U.S. church after separation occurs. After all, many traditionalists would not remain in the UM Church after separation and would therefore have no standing to determine how the UM Church is governed after separation. In fact, the Protocol for Separation envisions “The Council of Bishops will call the first session of the General Conference of the post-separation United Methodist Church to organize itself and, if such legislation has not been passed, consider matters pertaining to the Regional Conference plan.”

However, traditionalists would strenuously object to regionalization as a substitute for separation.

The key point to remember is that our church’s conflict is not geographical, and a geographical solution does not resolve the conflict. That was the fatal flaw of the One Church Plan rejected by the 2019 General Conference.

There are traditionalist congregations and clergy in every annual conference in the U.S. and Western Europe, which regions might be expected to go progressive. There are progressive congregations and clergy in the Philippines and parts of Africa, which might be expected to go traditional. Allowing regionalization without a fair and practical exit path for congregations would simply exacerbate the conflict within these regions.

Creating the U.S. as a separate region of the church without allowing for separation would simply trap traditionalists in a centrist/progressive church, with no real recourse to withdraw, other than to leave behind buildings and assets. (The current exit path adopted by the 2019 General Conference is too expensive for most congregations, requiring seven to twelve years’ worth of apportionments as the fee to keep their buildings.) Under such a scenario, traditionalists are afraid that they would eventually be forced out of the church by the centrist/progressive conference leadership, so that the conference could keep the congregation’s building and assets to support the conference’s dwindling finances.

Some proponents of regionalization maintain that, while the U.S. church would change its stance on marriage and ordination, it would continue to welcome traditionalists to remain in the church. However, such hospitality could not be guaranteed. The Episcopal Church in the U.S. started out welcoming traditionalists to remain in that church after it changed its teachings, but now it appears that all parts of the church are expected to allow same-sex marriage and ordination of practicing LGBT persons, and its last traditionalist bishop has just resigned. If affirming same-sex relationships is truly a justice issue, which is how most centrists and progressives see it, they could not allow what they view as “discrimination” to continue indefinitely. Sooner or later, they would have to require same-sex marriage and ordination in all parts of the U.S. church.

Even now, given the way the election of jurisdictional delegates took place in 2019, there is no jurisdiction in the U.S. that is likely to elect a traditionalist bishop in the foreseeable future. Many progressive annual conferences refuse to ordain traditionalists as clergy. The track record of hospitality to traditionalists in progressive areas is not reassuring.

The regionalization plans, whether it is the Christmas Covenant or the Connectional Table Plan, should not be seen as a substitute for separation. Amicable separation is the only pathway that would truly end the church’s conflict and allow freedom of conscience on the part of all clergy and congregations, whether centrist, progressive, or traditionalist. General Conference delegates should defeat any attempt to enact regionalization without also enacting the Protocol for Separation.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Mar 5, 2021 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Thomas Lambrecht –

By Thomas Lambrecht –

Sometimes in life, there is no substitute for a fresh start. That is what the newly announced Global Methodist Church (GMC) offers.

Texas experienced near-record freezing temperatures a couple weeks ago. As a native of Wisconsin, I’m used to the cold, but the plants in our yard were not chosen according to their ability to survive freezing temperatures. Most of them look pretty bedraggled right now. I spent last weekend clearing out and discarding all the dead leaves, stems, and plants so they have room to grow back from their roots. It would do no good to leave all that dead plant material on the ground, since those plants will not reenergize the existing leaves and stems. They will only survive by growing again from the roots.

That is how many traditionalists perceive The United Methodist Church. Parts of the church have lost their ability to function the way they were intended. Rather than fighting to reenergize those dead leaves and stems, it will be more fruitful to clear away the debris and start fresh, allowing Methodism to grow up once again from its historic roots.

The newly announced Global Methodist Church represents an effort to reconstitute Methodism in a new way for the 21st century, while drawing upon our biblical and Wesleyan roots. This project reminds me of the words of Jesus to the church in Sardis: “I know your deeds; you have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead. Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die” (Revelation 3:1-2). The GMC is an attempt to strengthen what remains and reconstruct what is missing from original Methodism in a way that works for this new century.

A Fresh Theological Identity

The greatest error the founders of United Methodism made in 1968 was to create a theological identity around doctrinal pluralism. The concept was that the church could accommodate a variety of theological perspectives and belief systems. Even now, there are some clergy who do not believe in the bodily resurrection of Jesus, the Virgin Birth, the validity of miracles, or the necessity of Christ’s death on the cross for our sins (to name a few).

As a result, United Methodism has no clear theological identity. When one walks into a United Methodist local church, one never knows what theology will be preached from the pulpit that Sunday.

The Global Methodist Church gives us a chance to start fresh with a consistent theological identity. It will be based on the ancient creeds and the Articles of Religion and Confession of Faith. All GMC clergy and congregations will be expected to affirm and teach these doctrines without their fingers crossed behind their backs and without “redefining” what the creeds mean. While there will be room for theological exploration and diversity of perspective on lesser matters, there will be no dispute over the main points of our doctrinal understanding.

Fresh Accountability

The situation that has precipitated the crisis in United Methodism is the lack of accountability. There is currently no way to hold bishops accountable to enforce the provisions and requirements of the Book of Discipline. They can choose not to do so, and many U.S. bishops have chosen not to hold clergy and annual conferences accountable to the requirements regarding same-sex weddings and the ordination of self-avowed practicing gay and lesbian persons as ministers. This results in clergy who are also unaccountable, choosing which parts of the Discipline to honor and which parts to ignore. The UM Church has become, in some sense, ungovernable. Restoring accountability would be a long, painful process with an uncertain prognosis of success.

The Global Methodist Church offers an opportunity to reestablish uniform accountability for bishops and clergy. All will be held to the same global standards. Uniform accountability processes will ensure that bishops in particular abide by the requirements of the new church’s Book of Doctrines and Discipline. That accountability is possible because all will agree to abide by those requirements from the beginning.

But accountability is not just for bishops and clergy. The essence of Wesleyanism is accountable discipleship for all believers. The small group meetings called classes and bands were an essential part of Methodism for at least its first 100 years. And it was the fading vitality of such small groups that led to the cooling of Methodist fervor in its second 100 years.

The GMC hopes to restore small-group discipleship as an essential part of church membership. We all need accountability in our daily transformation toward greater Christlikeness. We were not meant to live the Christian life as “holy solitaries” (in Wesley’s words). Rather, we are called to live in Christian community, strengthening and encouraging one another in our walk with the Lord. We need to know and be known by a small group of brothers or sisters, comrades in arms, who are fighting the spiritual battle of holiness with us.

A Fresh Approach to Ministry

In United Methodism, the denominational hierarchy and general boards and agencies have become disconnected from the local church. Like independent fiefdoms, each has its own identity and mission that are only loosely accountable to the general church. Sometimes, these agencies have constituted their own power center within the church that serves mainly to perpetuate its institutional existence, rather than providing vital services to local churches and annual conferences.

The Global Methodist Church aims to flip this picture upside down, where the hierarchy becomes the “lowerarchy.” The role of bishops, superintendents (to be called presiding elders), staff, and boards and agencies is to serve the local church and facilitate the ministry of the local church. Their effectiveness will be judged, not on power or prestige, but on how well they are able to serve the local church.

Structurally, the emphasis will be on flexibility and lean organization. Essential functions will be mandated, but how those functions are carried out will be up to each local church and each annual conference. Local churches, conferences, and the general church will be encouraged to form only those committees and agencies that are essential, rather than proliferating a bureaucracy that becomes a self-promoting entity.

General church agencies will strive for a unity of mission and cooperation in service to the church. They will be accountable to a Connectional Council that will ensure agencies do not become independent silos or get off-mission. Agencies will share staff, and a connectional operating officer will be responsible to keep agencies and staff centered on their cooperative mission to serve the larger church.

A Fresh Approach to Ordained Ministry

The United Methodist Church has struggled for decades to find a unified and coherent understanding of ordained ministry. Its increasing reliance on licensed local pastors in lieu of ordained clergy has established a “class” system that separates one type of clergy from another, resulting in unfair treatment of those perceived to be in a different “class.” Its long process leading to ordination over six to twelve years discourages many from pursuing that goal and no longer fits a global church with a variety of cultural, educational, and financial circumstances.

The Global Methodist Church proposes restoring a nested understanding of ordination. All laity are called to ministry in the world and in the church. Deacons are called out of the laity to a representative ministry of service and word to lead the church in ministry to the world. Elders are called out of the order of deacons to a ministry of service, word, sacrament, and order to lead the church in ministry to the world. Some will remain permanent deacons, but all elders will be deacons first. (Further in-depth explanation of this understanding is available in three articles HERE, HERE, and HERE.)

Ordination as a deacon will be available after as little as one year of candidacy. There will no longer be licensed local pastors serving churches. Instead, they will be ordained as deacons, while they continue their education toward ordination as elders. The goal is to have an ordained deacon or elder serving as the pastor of nearly every local church. Deacons and elders will have sacramental authority, deacons in their ministry setting and elders in all settings.

A variety of educational routes will be available for those seeking ordination as elders, including the traditional Master of Divinity, Course of Study, or Bachelor or Master of Arts in Ministry. Pastoral training will emphasize practical experience in ministry during training and provide for continued supervision in ministry following the completion of education.

Educational loans will be available to certified candidates for ministry, with such loans being forgivable in exchange for five years of service in the church. The goal is to release all clergy from educational debt.

Any separation of a denomination is tragic. I wish it had not come to this. However, it seems we have two main tasks in light of the evident need for separation:

- To make separation as fair and as amicable as possible, not using this as a final opportunity to exact one more pound of flesh from our opponents. We have a chance to demonstrate to the world that, if we cannot live together, at least we can separate in a way that exhibits the fruit of the Holy Spirit and fulfills Jesus’ wish that we be peacemakers.

- To use this separation as an opportunity for a fresh start, not only for the new Global Methodist Church, but also for the continuing United Methodist Church. Let’s not waste this crisis by trying to hang on to the status quo. Rather, we can think creatively and innovatively about how to best position our churches for the task of ministry ahead in this 21st

A fresh start can help us all. After all, Christianity is the faith of the fresh start, found for each one of us as we become one with Jesus Christ in his resurrection to new life.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Mar 1, 2021 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Thomas Lambrecht –

By Thomas Lambrecht –

On Thursday, the Commission on the General Conference announced that the 2020 General Conference, postponed once until August 29, 2021, has now been postponed again until August 29, 2022. At the same time, the Council of Bishops announced it is calling a special session of the General Conference to meet virtually on May 8, 2021, to address technical issues that would allow the church to continue operating until the full General Conference can meet.

The Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation is not currently on the agenda for the special virtual General Conference.

No Regular General Conference

The Commission made the expected decision that an in-person General Conference could not take place in 2021, due to the travel restrictions in place now and expected to remain in place for the foreseeable future. Travel by delegates from outside the U.S. to attend General Conference will likely still be impossible throughout 2021. Those delegates make up 40 percent of the General Conference, and it would be inappropriate to meet without them.

A Technology Study Team met during January to consider the possibility of a virtual General Conference. After extensive research and conversations with representatives of the church outside the U.S., the team concluded that a virtual General Conference, even with a limited agenda, would not be possible. Some of the reasons for this conclusion are:

- The technology for linking different parts of the world would only accommodate six to ten sites, meaning that delegates would need to gather in central locations in groups of 50 to 100. Due to travel restrictions, both inside and outside the U.S., such travel appears unlikely or impossible.

- Some of the sites for gathering outside the U.S. do not have reliable electricity and Internet service, meaning that particular sites might not be available at the time the General Conference is supposed to meet during the day, and their ability to interact could be severely compromised. Travel restrictions limit the ability of technical teams from the U.S. to travel to the sites to set up the required technology. It would not be ethical for the General Conference to meet if not all delegates have equal ability to contribute their voice and participate in holy conferencing.

- In the wake of problems at the 2019 General Conference with improper voting, there needs to be a way to assure the identity of delegates and reserve delegates in order to assure the integrity of the process. This can only be effectively assured by the presence of trained staff and volunteers from the Commission. Travel restrictions would inhibit the ability of staff and volunteers to attend the sites outside the U.S.

- Concerns have been expressed about undue influence being exerted on delegates to vote certain ways. The only way to mitigate against that is for neutral observers to be present, which is again inhibited by the travel restrictions.

As one who promoted the viability of a virtual General Conference, reading the report of the Technology Study Team convinced me that it is not feasible with current technology during a pandemic. This decision is disappointing, and the situation is frustrating, but I believe it was the right call.

The Special Session

The Council of Bishops proposes that the special session gather on May 8 for an extremely limited agenda. The first task would be to secure a quorum in order for the special session to take action. In light of the above considerations, it is unlikely that more than a scattered few delegates from Africa or the Philippines could attend. It must be acknowledged that, despite the high value on universal participation by all delegates, this special session will mainly include U.S. and European delegates who have access to Internet technology. But this situation is unavoidable in trying to get some of the church’s administrative processes unstuck.

With the knowledge that many delegates could not participate in a deliberative General Conference, the Council of Bishops has limited the proposed agenda to twelve administrative items that it considers non-controversial. These agenda items provide for:

- Correcting the accountability process in response to a Judicial Council ruling invalidating the entire administrative process for dealing with ineffective clergy

- Allowing the General Conference and central conferences in extraordinary circumstances to be held electronically (Note that jurisdictional conferences are not given the same explicit ability to meet electronically, although the bishops’ press release envisions a virtual jurisdictional conference this summer to act on the retirement of bishops and determine new episcopal areas.)

- Allowing the central conferences to meet during the last half of 2021 to determine whether or not to elect bishops this quadrennium to replace those who are retiring (It is unclear whether actual elections would take place then or at an in-person central conference meeting held following the 2022 General Conference. As of now, it appears that the five additional bishops for Africa promised in 2016 are off the table until at least 2022.)

- Providing that bishops who reach age 72 are automatically retired and allowing younger bishops to retire at their request, rather than having to wait until a jurisdictional or central conference meets to vote on their retirement

- Providing that, if the General Conference cannot meet as scheduled, the budget for the previous quadrennium will be extended until such meeting can occur

- Allowing annual conferences to elect quadrennial officers if the General Conference cannot meet as scheduled

The virtual General Conference will also vote to allow the voting on the above items to be done by paper ballots that would be compiled by mail and the results announced on July 13, 2021. The paper ballots would not allow any amendments to the above legislation. Delegates would simply vote yes or no. Although not all delegates could participate in the virtual General Conference, all 862 delegates could cast paper ballots on the proposed legislation.

What about the Protocol?

The agenda for the virtual special session of General Conference does not include the Protocol to allow for separation in the UM Church. Some have said that such a decision is too important to be made when we are not together in the same room. Further, the items on the special session agenda could not be amended, and some have said they want to make amendments to the Protocol.

However, the decision about separation requires urgent resolution. Many of the other decisions, such as the budget and the number of bishops to elect, depend upon how many churches and annual conferences will remain in The United Methodist Church after separation. It would be better to make the decision regarding separation before needing to make all these other decisions.

It is in no one’s best interest to prolong this decision. Deciding now would enable The UM Church and the new traditionalist denomination to begin moving ahead in ministry as we come out of the pandemic. Many are ready to act, and deciding now would open the door for churches that are ready to go in a new direction. The Protocol has been discussed publicly for over a year, so the delegates are well aware of what it contains.

It is in the best interest of centrists and progressives that General Conference make a decision now regarding the Protocol. Once traditionalists start moving to a new denomination, it would allow centrists and progressives free rein to change the church’s position on marriage and sexual ethics, as well as enact new structures of regionalization at the 2022 General Conference. If the decision on separation is postponed to 2022, it is likely that these other changes will have to wait until 2024.

The need to offer amendments to the Protocol is not essential. The mediation team negotiated the major terms of the Protocol based on compromise and give-and-take. Changing any of those major terms could jeopardize the carefully balanced agreement and throw the adoption of the Protocol into question. It would be better to adopt the Protocol as negotiated, with the implementation dates extended by one year, which would be possible under the plan of the special virtual session.

The Council of Bishops could amend the call for the special session to include the Protocol, but they are unlikely to do so. By a two-thirds vote, the delegates could add the Protocol to the agenda of items to be dealt with by the special session. Coming weeks will show if this is a viable option.

Hope for the Future

Meanwhile, we look to the Protocol mediation team to provide leadership in continuing its support and promotion of the Protocol. The Reconciling Ministries Network and the Western Jurisdiction and its progressive bishops have recently reiterated their support for the Protocol, as has the Atlanta group of traditionalists. With support across the spectrum, including from bishops, the Protocol can move forward as a positive way to amicably resolve the decades-long conflict in the UM Church.

Whether the decision is made in May or next year, we believe an amicable separation will release the church to be what its members determine. Freed from conflict, both groups could wholeheartedly pursue ministry according to their mission and identity. They could focus their energy on mission, and no longer be distracted by conflict.

Over the past year, we have been learning to endure and persevere. Yes, it is tiring, hard work. It is discouraging at times to see the goal line shift farther into the future, whether we are thinking about the pandemic or the future of the church. The promise remains that God is with us and will never leave or forsake us.

Be patient, then, brothers and sisters, until the Lord’s coming. See how the farmer waits to see the land yield its valuable crop, patiently waiting for the autumn and spring rains. You too, be patient and stand firm, because the Lord’s coming is near (James 5:7-8).

Patient endurance is our calling in this moment. As we see what God unfolds in our lives and the life of our church, we put our faith and trust in him. With Jeremiah, we are confident that God has “plans to prosper [us] and not to harm [us], plans to give [us] hope and a future” (Jeremiah 29:11). We can stand firm on that promise and the Lord’s matchless presence at all times. “Do not be afraid. Stand firm, and you will see the deliverance the Lord will bring you today” (Exodus 14:13).

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Feb 19, 2021 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Thomas Lambrecht –

I recently expounded the primary reasons I see for separation taking place in The United Methodist Church. That article drew the response of the Rev. Adam Hamilton, who felt that my characterization of centrist and progressive understandings was not an accurate description.

I recently expounded the primary reasons I see for separation taking place in The United Methodist Church. That article drew the response of the Rev. Adam Hamilton, who felt that my characterization of centrist and progressive understandings was not an accurate description.

I respect Adam and the vibrant ministry he has led at Church of the Resurrection. I have used some of his Bible study materials and found them helpful. His views on Scripture have appeared to evolve over time, however, and some statements in his 2014 book Making Sense of the Bible seem to reflect an approach to Scripture at odds with that of most traditional Methodists. In this article, I would like to delve a bit deeper into our differences.

The Primacy of Scripture

I focus on the traditionalist/evangelical understanding of Scripture as the primary authority for what we are to believe and teach as Methodist Christians. In his response to my article, Hamilton writes, “nearly every United Methodist I know believes … that Scripture is primary in determining what we believe, and tradition, reason, and experience are secondary.” He elaborates, “I do not know anyone who sees tradition, experience, and reason as equal to Scripture.”

An interesting survey of United Methodist members in 2018 done by United Methodist Communications asked the question, “What is the most authoritative source of your personal theology?” Scripture was identified as the number one source by 6 percent of self-identified progressives/liberals, 25 percent of moderates/centrists, and 41 percent of conservatives/traditionalists. In fact, Scripture was identified as the number three source of theology, after reason and tradition, by moderates/centrists. And for progressives, Scripture was the least important source of theology.

Granted, the subjects of the study were laity, not clergy. But it appears that there is a distinct difference in approaching Scripture between progressives, centrists, and traditionalists in general. I have to believe that at least some of this difference is due to their pastors, who reflected that difference of approach in their teaching and preaching.

A glaring example of that approach is the clergy delegate at a General Conference years ago who stood up on the floor of conference and said, “We don’t go back to the Bible for the last word on anything.” There may be more people in the church than Hamilton realizes who hold a different view of Scripture, for whom Scripture is not primary in guiding our beliefs and actions.

Hamilton’s statement of his beliefs about the Bible’s inspiration demonstrates the difference between a centrist understanding of Scripture and that of a traditionalist. “Divine influence on the writers [of Scripture] was not qualitatively different from the way God inspires or influences [people] by the Spirit today,” Hamilton writes. “The difference between biblical texts and some contemporary writings also influenced by the Spirit is that the biblical authors lived closer to the events of which they wrote. … This view allows us to value the Bible, to hear God speaking through it, yet … to recognize that some things taught in scripture may not represent God’s character nor his will for us today, and perhaps never accurately captured God’s will” (Making Sense of the Bible, p. 143).

By contrast, most traditionalists believe the Bible is “God-breathed,” which is why we can receive it as “the true rule and guide for faith and practice” (Confession of Faith, Article IV). If all Scripture is not God-breathed, but only some parts of it, how can we view it as our true rule and guide? This morphs over very easily into making ourselves and our own ideas the true rule and guide, since it is we who decide which parts of Scripture to regard as authoritative. If something in Scripture does not make sense to us or does not fit our cultural perspective, we can too easily discard it as one of those “not inspired” parts, rather than allowing Scripture to correct our understanding or cultural myopia.

Scripture and Culture

In my article, it was my contention that many centrists and progressives believe, “when modern knowledge contradicts our understanding of Scripture, we must change our understanding of Scripture. … Human knowledge and understandings are more important than any long-standing perception of what Scripture teaches.” This is seen among those who have changed their understanding of Scripture’s teaching on marriage and sexuality due to recent cultural shifts.

In reply, Adam names a number of illustrations where he claims new knowledge and a changing cultural perspective have altered the church’s interpretation of Scripture.

Hamilton puts forward the narrative that many preachers in the 1800’s promoted slavery as consistent with, if not commanded by, Scripture. It was only as American society came to reject slavery that such an interpretation became untenable. Tragically, however, the legacy of slavery is still with us in Jim Crow attitudes and racist practices among some in our society even today. So, I do not think we can regard the “progress” of society as the source for a changed view of slavery.

Historically, the progression was just the opposite. The early Methodists in England and America were adamantly against slavery. The early Book of Discipline forbade Methodists from owning slaves. However, as the church began to grow after the Revolutionary War, southern Methodists complained that the church’s stance on slavery was hurting their ability to evangelize among the slave-holding population. Because of this cultural influence, the church’s stance on slavery was weakened, and it was eventually not enforced in southern states. It was when the northern annual conferences wanted to enforce the slavery prohibition against a particular slave-owning bishop that the southern Methodists rebelled and forced a schism in the church in 1844. They removed the prohibition against owning slaves from their Discipline and rationalized that slavery (and, in some cases after the Civil War, racism) was God’s will.

Accommodation to a slave-owning and racist culture caused the church’s interpretation to change in a negative way. That is what we see happening today with the changing definition of marriage and affirmation of same-sex relationships.

The same could be said about women in leadership in the church. There are prominent examples of female leaders in the Bible, as well as in early Methodism. Not least among those examples was John and Charles Wesley’s own mother Susannah, who was in many ways a co-pastor with her husband. There were women leaders in early American Methodism, as well. Yet after its explosive growth on the frontier, the church failed to adjust its practice in line with its understanding of Scripture, and instead allowed the desire for social respectability to limit the leadership of women in the church. It was actually a return to its former understanding of the priesthood of all believers that enabled first the Evangelicals and United Brethren, and finally the Methodists to recover the equal role of women in leadership.

Here again, our society is not a stellar example of women’s equality, what with the gender pay gap and the paucity of female business and political leaders. It is just as fair to say that churches like the UM Church are leading society in this regard, rather than being influenced by society in our understanding of Scripture.

Truth and Identity

Adam questions my claim that “most centrists and progressives reject the idea of absolute truth.” However, that is not what I claimed. The actual quote is, “Most centrists and progressives value self-determination as the deciding factor in one’s view of oneself.” I say this is connected to the idea that “truth is defined by each person for themselves.”

I am heartened to hear Hamilton’s assessment that “Most United Methodists … would agree that God is absolute Truth, that Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. That the Holy Spirit leads us into all truth. And that Scripture bears witness to God’s truth.” I would say that Scripture does more than bear witness to God’s truth – it reveals and teaches God’s truth. Aside from that quibble, I can affirm Adam’s quote.

However, I have not found that to be universally true in my interaction with United Methodist clergy. Some of my colleagues do not believe the doctrines we are “required” to believe in our doctrinal standards, particularly the Articles of Religion and the Confession of Faith. Some believe that everyone will go to heaven. Some believe Jesus did not need to die on the cross for our salvation. Some believe Jesus did not physically rise from the dead. There is not the universal agreement on the outworking of Adam’s quote above that he might think there is.

There are no better illustrations of people operating by their own “truth” than the One Church Plan, the Connectional Conference Plan, and the Christmas Covenant. Each of these plans envisions part of the church living by one truth, that the practice of homosexuality is contrary to God’s will. Another part of the same church would be living by another truth, that God affirms the practice of homosexuality. It is the ultimate example of self-defining truth attempting to coexist in one church body. The result is confusion and the loss of identity as to what it means to be a United Methodist Christian.

A Social Justice Agenda

Of course, Hamilton is right that we should “be unapologetic in pursuit of [social] justice.” The question is a matter of priorities.

The survey I cited earlier asked the question, “Which should be the primary focus of The United Methodist Church?” 68 percent of self-identified progressives/liberals said, “Advocating for social justice to transform this world.” Meanwhile, 68 percent of moderates/centrists and 88 percent of evangelicals/traditionalists said “saving souls for Jesus Christ.” Here, the demarcation is between progressives on the one hand and centrists and traditionalists on the other.

Most traditionalists perceive the denomination’s agenda as driven by the progressive “social justice” priority. Most of the general boards and agencies and most of the Council of Bishop statements have to do with issues of social justice. Aside from some good communication materials produced by UM Communications, most of the programs and resources produced by the general church have to do with social justice, with very little related to evangelism or discipleship.

More troubling to many conservative United Methodists is that often the positions promoted by the general church are in line with partisan policies advocated by one political party in the U.S. Politically conservative positions are not considered, and thus politically conservative United Methodists feel marginalized and even chastised by their church.

I agree with Adam that, “we are to live the gospel, doing justice, practicing kindness, being the hands and feet of Christ in addressing the brokenness in our world.” But we cannot live the gospel if we never hear the gospel, if we are never called to respond to the gospel call of Christ, or if we are never ushered into the lifelong discipleship of Jesus. I know these things are present in Hamilton’s ministry at Church of the Resurrection, but they are often missing from many congregations across our church and from the leadership of the general church.

Breakdown of the Church’s Governance

In my original post, I state, “When significant portions of the church refuse to abide by that church’s governance processes, the church’s unity is no longer viable. Ordained clergy vow to abide by the church’s tenets, even when we disagree, but many now are renouncing that vow by their actions and words.” Adam acknowledges this point, but has no answer for it.

Many traditionalists are outraged that the consistent and continual will of the General Conference quadrennium after quadrennium can be summarily ignored and set aside by some bishops, clergy, and annual conference boards of ordained ministry who disagree with the outcome.

My colleague, the Rev. Forbes Matonga of Zimbabwe, put it well when he said, “Africans expected to see their American counterparts who are generally perceived as champions of constitutionalism and democracy to show them by example how democratic institutions and systems work. This was a massive let down. We began to be taught new lessons, that minority voices override majority vote. That when you don’t have it your way then you make the institution ungovernable. That you only follow the law when it is in sync with your cultural beliefs.”

For traditionalists, this last straw breaks the camel’s back. We could and did abide differences of opinion and belief for 40 years in the UM Church. But when widespread schism through disobedience to the order and discipline of the church began, it became apparent that we could not all go on together as part of one church body.

I appreciate the opportunity to exchange views with Adam Hamilton. It clarifies our understanding of each other. As we approach the possibility of separation within The United Methodist Church, clarity of communication and understanding will be important. It is our contention that after 50 years of conflict over the issues above, it is time to go our separate ways. Each person and each congregation will have an opportunity to decide what their beliefs and direction will be. As we prayerfully make these decisions, our goal is that we separate amicably, blessing one another, and allow each group to pursue its ministry in the way it feels led by God to do so. There is no benefit to continuing a conflict that only detracts from our church’s focus on mission and ministry.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Feb 15, 2021 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Thomas Lambrecht –

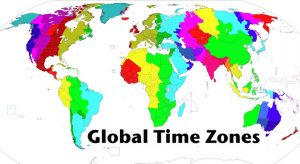

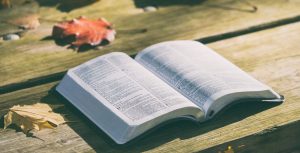

Global Time Zones.

In last week’s Perspective, I outlined why an in-person General Conference in 2021 is unlikely to occur as scheduled. The virulence of the Coronavirus pandemic and the slow rollout of vaccines to the global population make a return of international travel unlikely before mid-2022.

I also made the case that some type of General Conference must occur in order to deal with the budget, set the apportionment formula, and elect members to the Judicial Council and other bodies. I also suggested the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation needs to be enacted this year to avoid the splintering of the denomination and potentially expensive litigation by congregations and annual conferences.

Moving forward with separation is a prerequisite for making other decisions about the post-separation United Methodist Church, including the Christmas Covenant idea that regionalizes church governance. Individuals with a long-term commitment to The United Methodist Church need to make those decisions.

The most likely scenario for General Conference is that it will be held virtually with a limited agenda. This is how almost all annual conferences met in 2020, particularly in the U.S. and Europe. With a limited agenda, it could operate like the 2019 General Conference, as a committee of the whole without breaking up into legislative committees. Petitions not included in the limited agenda could be tabled or referred to the next in-person General Conference.

In this article, I examine how a virtual meeting could happen and some of the obstacles we would need to overcome.

A Distributed General Conference

The most realistic way a virtual General Conference could take place is through what missiologist David Scott called a distributed General Conference. This would involve delegates gathering in regional groups to participate together in a global virtual General Conference. Regional gatherings are the only practical way for delegates in Africa, the Philippines, and parts of Europe to have sufficient Internet access in order to participate. If these delegates need to gather regionally in order to participate, all the other delegates should do so as well, so everyone is treated equally and fairly.

Depending upon the travel situation with the pandemic and the availability of Internet access, delegates outside the U.S. could gather in episcopal areas (which sometimes include several annual conferences) or even in central conference groupings. In the U.S., delegates might gather by annual conference or several annual conferences could gather in one place.

Bishops could preside over these regional gatherings of delegates for the purpose of engaging the delegates in discussion, questions, and debate about particular business items. There would be shorter plenary sessions via the Internet that would bring all the regional groups of delegates together to take action on proposals.

What Time Is It?

Perhaps the biggest logistical obstacle is the different time zones. When it is 8 am in Chicago, it is 3 pm in West Africa and Western Europe, it is 5 pm in East Africa and Moscow, it is 6 am in California, and it is 10 pm in the Philippines. No matter what time is chosen for plenary meetings, someone will be inconvenienced.

The starting times proposed above might inconvenience the smallest number of delegates for a three- or four-hour plenary. Another alternative would be for the Western Jurisdiction delegates to meet in a mid-America city and create a “bubble” for meeting together there. The Filipino delegates could do the same by flying to the Middle East (where there are major Filipino populations) and meeting in a hotel there. (Travel, hotel, and meals for all delegates would be paid by the general church.) This minimal travel outside their home area would reduce the inconvenience for Western Jurisdiction and Filipino delegates. (As a side benefit, most delegates would not have to travel long distances and would not have to cope with drastic time changes in their internal clocks.)

Since the length of each day’s plenary would be so short, the regional gatherings of delegates could use the time either before or after the plenary to hear presentations, ask questions, and enter into discussion and debate. They would then be ready to take action during the plenary sessions. Such an approach would maximize the use of time, while keeping the plenary manageable in length and complexity.

Can You Hear Me Now?

The other major logistical obstacle is assuring adequate Internet access for the regional delegate gatherings, particularly in Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Philippines. With a limited agenda, and even with shortened plenary sessions, a four-day General Conference should be enough time to accomplish the essential business. With travel being more localized and much lower hotel and food costs, the General Conference budget could provide extra funds to set up Internet nodes where needed for the regional gatherings. In some cases, we could set up the nodes in annual conference office buildings, which would yield a lasting benefit for the annual conference to use beyond just the General Conference meeting. With a six-month lead time, surely we could overcome the technological barriers.

The Need for Integrity

The fact that a handful of voters at the 2019 General Conference were not authorized delegates points to the need to ensure the integrity of the participating delegates. Trained observers functioning on behalf of the Commission on the General Conference could attend each regional site and authenticate the credentials of delegates. The observers could also monitor the proceedings at each site to ensure that there is no manipulation or undue influence upon delegates, and that they have the freedom to discuss all the relevant issues.

How to Handle Amendments and Questions

For those of us who have participated in virtual annual conference sessions, the most difficult aspect is fairly allowing questions to be asked and answered, as well as considering amendments to any proposal. The time lag between the presider and any person asking for the floor made the process go very slowly.

One way to address this would be to use the time either before or after the plenary session each day to surface questions and potential amendments. Questions posed in the regional groups could be forwarded to the General Conference secretary. A time could be built into the agenda of the next plenary session to hear those questions and the answers. That way, all the delegates would have the benefit of hearing the questions raised and answered.

The rules could stipulate that proposed amendments would first have to be adopted by the regional gathering of delegates in order to be considered by the plenary. If adopted by the regional gathering, the amendment could be forwarded to the General Conference secretary and prepared to be introduced at the appropriate plenary. This process would cut down on multiple amendments and provide an orderly way to get them before the body. Speeches could be rotated among the regional gatherings, so that all parts of the church can fairly participate in the discussion. The fact that delegates could speak in their regional gathering might also cut down on the number of speeches needed during the plenary sessions.

Can You Understand Me?

Translators would need to be present at the regional gatherings that needed them. Delegates who need translation could request it, enabling the most efficient assignment of translators to the venues where needed. The use of local translators could reduce cost. To further maximize the use of time, presentations could be recorded ahead of time and translation could be dubbed in. The presentations could be shown at the regional gatherings before or after the plenary in the language that works for the delegates in that regional gathering. One set of translators could be available during each plenary session to translate on a separate channel for all the delegates who need that translation.

Is This Legal?

Concerns have been raised that the Book of Discipline does not provide for a virtual General Conference, or that the Judicial Council would rule the process adopted unconstitutional. However, the Discipline gives the General Conference the power to set its own rules. The 2019 General Conference operated by a different set of rules from a normal, in-person General Conference. Virtual annual conference meetings in 2020 operated by different sets of rules from the normal annual conference. Of course, virtual annual conferences are not provided for in the Discipline, either, but they were held in 2020 and may be held again in 2021.

If the rules are carefully drafted, using the experience of many annual conferences last year, they can be drawn within the boundaries established by the Discipline. The first order of business would be for the delegates to adopt those rules authorizing a virtual/distributed General Conference. Once that is done, there is little chance that the Judicial Council would rule such a process unconstitutional.

The bottom line is that a virtual/distributed General Conference is doable. There may be issues I have not considered that might rule it out, but it would be best to try it. We would all prefer to meet in person, but in the absence of that possibility, a virtual General Conference can take care of the necessary business to enable the denomination to move forward into the future.

Given the uncertainty and the long-lasting nature of the pandemic, the earliest we could reasonably hold an in-person General Conference might be fall of 2022. Even then, it might need to be postponed until spring of 2023. The church simply cannot remain stuck in the current situation for another year or two. With some cooperation and goodwill on the part of groups across the theological spectrum, we can adopt the plan of separation and congregations and annual conferences can freely choose the kind of church of which they want to be part. The fellowship of the committed in each church can then move forward with alignment in mission, vision, and belief. That is the only recipe that allows for a faithful and positive future for all United Methodists.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

By Thomas Lambrecht –

By Thomas Lambrecht – By Thomas Lambrecht –

By Thomas Lambrecht – I recently expounded the primary

I recently expounded the primary