By Beth Felker Jones –

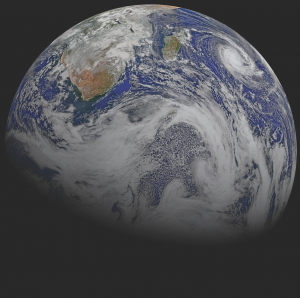

Composite image of southern Africa and the surrounding oceans captured by six orbits of the NASA/NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership spacecraft.

“And he showed me more, a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, on the palm of my hand, round like a ball. I looked at it thoughtfully and wondered, ‘What is this?’ And the answer came, ‘It is all that is made.’ I marveled that it continued to exist and did not suddenly disintegrate; it was so small. And again my mind supplied the answer, ‘It exists, both now and forever, because God loves it.’ In short, everything owes its existence to the love of God.”

These words are from Julian of Norwich, a medieval Christian who recorded a number of revelations of God’s love. The vision above, in which God shows “all that is made” to Julian in the form of “a little thing, the size of a hazelnut,” is one of the most well-known of Julian’s revelations. In light of this vision of creation’s fragility, of its utter dependence on God, Julian marvels that it exists at all, and she draws three truths from it.

The first is that God made it; the second is that God loves it; and the third is that God sustains it.

In these elegant points, Julian sums up the Christian doctrine of creation, and she does so in a way that gets at both head and heart. The doctrine of creation is not first about the obvious trigger points in the contemporary North American conversation, and this means that we may require some retraining in order to practice the doctrine well. When we hear the word creation, we have been primed to expect either a tribute to nature or a scientific account of the origins of the universe.

We think of majestic wilderness and towering pines, or we think of evolution or dinosaurs or carbon dating. Christians may well have something to say about those things, but if we get hung up there, we miss the sweetness at the heart of the doctrine. Philosopher Janet Martin Soskice notes that “the biblical discussions of creation” are “concerned not so much with where the world came from as with who it came from, not so much with what kind of creation it was in the first place as with what kind of creation it was and is now.” The doctrine of creation is about the dependence of all things on God the Creator and, as Julian saw, the love the Creator bears for all that he has made.

This means that the doctrine of creation cannot begin with appreciation for natural beauty. Nor can it begin as a conversation with science. It must begin with the character of the God who is Creator, who made and loves and sustains all that is.

In relationship to creation, Christians tend to notice two things about the Triune God. First, God is not one of the things in this world, and so our doctrine about this world will have to take account of the unfathomable difference between it and God. God is utterly distinct from creation; that distinctiveness is behind the psalmist’s cry, “Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever you had formed the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God” (Ps. 90:2).

Second, the same God who is not of this world is nonetheless intimately involved in it. Indeed, creation depends on God for its ongoing existence at every moment. The doctrine of creation is about God, and so our education about it should begin not with creation itself but with God’s revealing Word. It is not by studying butterflies or stars but “by faith [that] we understand that the worlds were prepared by the word of God” (Heb. 11:3). The Triune God is not some generic god, and our doctrine of creation will have to be about the relationship between creation and this Creator, the Creator who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. “All things came into being through” the Word made flesh, Jesus Christ, “and without him not one thing came into being” (John 1:3).

This is the personal God who lives in personal relationship with creation. The doctrine of creation points us to faithful practice as creatures of a creator God, creatures who live in a world that exists for God’s loving purposes: “For we are what he has made us, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life” (Eph. 2:10). We are created in Christ Jesus, and we are created for Christ Jesus: “For in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers – all things have been created through him and for him” (Col. 1:16). Jesus is both the source and the purpose of creation. We live in a world that has a point, a world that matters. The good news that “all things” are “for him” has enormous implications for the Christian life.

God Made It: Creatio ex nihilo and the Power of God

Julian’s categories show that talk about the doctrine of creation is not limited to the beginning of all things – God’s original creative action in bringing all things into being – but Christian conversation certainly tends to start there. Scripture starts there too, as the familiar first line of Genesis invokes “the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1). The first chapters of Genesis show us a world in which God has made all things. Those first chapters set up a way of thinking about the God who created all that is and about God’s relationship with creation. Old Testament scholar Sandra Richter sums up the theological vision of the creation story, highlighting its distinction from ancient Israel’s neighbors.

“Yahweh was a god unlike the others of the ancient Near East, one who stood outside and above his creation, a god for whom there were no rivals and who had created humanity as his children as opposed to his slaves,” she writes. “Thus I think Genesis 1 was intended as a rehearsal of the creation event (where else would you start the story?) with the all-controlling theological agenda of explaining who God is and what his relationship to creation (and specifically humanity) looked like.”

Not just the first chapter of Genesis but also the whole of Scripture points to this creator God. The testimony of Genesis is that of the end of the Bible as well, of the book of Revelation, which praises God with the words, “You are worthy, our Lord and God, to receive glory and honor and power, for you created all things, and by your will they existed and were created” (Rev. 4:11). God the Creator has no rivals, yet all that is was made to be in loving relationship with the same sovereign God.

In the Christian tradition, the phrase “creation out of nothing” (in Latin, creatio ex nihilo) synthesizes and affirms the biblical testimony pointing to the kind of act with which God first created everything. God created all that is, the summary phrase announces, out of nothing. The phrase invokes the unchallenged majesty of the creator God, without whom nothing exists or ever has existed. The phrase also points, then, to the truth that all that exists, the totality of creation, is God’s work and belongs to God. There are no exceptions. In the words of the Nicene Creed, “all that is, seen and unseen,” is God’s. The implications of the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo can be better understood when we compare the doctrine to the false options that it excludes. If God created out of nothing, then God did not create out of something. Nor, if God created out of nothing, did God create out of his own divine being.

It is easy enough for us to think about acts of creation out of something. The sculptor creates from stone or clay, and the gods of Israel’s ancient Near Eastern neighbors were understood to create out of preexisting chaos or even out of the bodies of their slain enemies. Or, on certain understandings, a god might be understood to create from preexisting matter, from stuff that was already there alongside the god, primordial ooze or a hot, dense core of material that would later explode with a bang. The claim that God created, not out of something, but ex nihilo is a claim that nothing has status alongside God. The repeated testimony of Scripture is that only God is eternal; only God has no beginning; there is none like God.

To deny that God created out of preexisting stuff is to deny that anything, in all creation, has godlike status. In some ways, the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo is simply an implication of monotheism; it is one more way of affirming that “the LORD is our God, the LORD alone” (Deut. 6:4).

And because the doctrine of the Trinity is a deeper understanding of this core Old Testament reality, creatio ex nihilo is an implication of trinitarian theology as well. There is none like the Lord, none alongside him. The doctrine of creation denies that God created out of something – be it chaos or a sea dragon, primordial ooze or a hot, dense core – but it does not deny that God, having already created, then works in and with all sorts of created things. God’s initial act of creation is ex nihilo, but this does not preclude God’s working with and through that which he has created already. Christian thought has no problem with scientific theories about how creation works, but it cannot bear the idolatry of scientism, which would reduce creation to what can be seen and measured. A world that God created from nothing cannot be a world of bare materialism, bereft of divine reality. A world that God created from nothing cannot be the world of deism, in which God holds back, distant and standoffish, from what he has made. A world ex nihilo is, instead, a world full of God’s presence and power.

To deny that God creates out of his own divine being is to recognize the difference between God and creation. This difference is fundamental to Christian thought, and being reminded of it is the ongoing stuff of Christian life. We can imagine acts of creation out of one’s own being. Reproduction works as an analogy. An infant is formed from the stuff of her parents, hydras reproduce new hydras by budding, and both human babies and newly budded hydras are of the same species as their “creators.”

We could envision a god who fashioned creation out of his own being, making a creation that would itself be divine. The whole world as we see it in Scripture, though, which shows us the God who is more than we can conceive and beyond the things of this world, teaches us something else. So, Christian thought consistently rejects all forms of pantheism, the belief that the world is itself divine, and panentheism, the belief that God and the world are so bound together that God could not exist without the world. Christians see, instead, a measureless and qualitative distinction between Creator and creature, between God and all that has been created.

God is God, and we are not. This is another way in which affirmation of God as Creator ex nihilo is a reaffirmation of the biblical proscription against idolatry. Sinful human beings repeatedly confuse creature and Creator, treating the world as divine, exchanging “the truth about God for a lie” and worshiping and serving “the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom. 1:25), but the doctrine of creation trains us in another direction, reminding us that there is no god but God. The doctrine of creation affirms the goodness of what God has made, but it makes no allowance for nature cults and zero room for worshiping human beings and pursuing selfish human ends. The doctrine of creation puts Creator and created in their proper places, insisting that created good things are always dependent, always finite, and always subordinate to the Creator.

God does not need creation in order to be who God is; God is not lacking in love or goodness or relationship in any way that makes creation necessary. Theologian Stephen Long explicates, “God does not create because God is lonely. God does not create because God needs friends. God is not the lone patriarch, the strong silent type who secretly desires to ‘open up’ to us but cannot do so without our help. God does not create because God has to.” In this, we can appreciate a great gift. God creates, not because God needs us, but because God wants us. So, Rowan Williams asks us “to bend our minds around the admittedly tough notion that we exist because of an utterly unconditional generosity: The love that God shows in making the world, like the love he shows towards the world once it is created, has no shadow or shred of self-directed purpose in it; it is entirely and unreservedly given for our sake. It is not a concealed way for God to get something out of it for himself, because that would make nonsense of what we believe is God’s eternal nature.”

Creation is the overflowing of God’s goodness and love outside of God’s own life. Creation is excessive. Creation has all the characteristics of a good gift: it is freely given, without constraint; it is given in love for the other, without selfishness; it is not a grasping, grudging thing, with so many strings attached. Creation is the free work of an all-sufficient God of abundance, the God whose love and mercy is always more than we can imagine. Athanasius (c. 296-373) rejoices: “For God is good – or rather, of all goodness He is Fountainhead, and it is impossible for one who is good to be mean or grudging about anything. Grudging existence to none therefore, He made all things out of nothing through his own Word, our Lord Jesus Christ.” Creation is made for relationship with this gift-giving God, and “its basis,” says theologian Kathryn Tanner, is “in nothing but God’s free love for us. The proper starting point for considering our created nature is therefore grace.”

The doctrine of creation out of nothing is thus the Christian alternative to other possible ways of understanding the origins of all things. Christian faith is not pantheistic, nor does it subscribe to bare materialism or cold deism. Rather, Christians worship the God who is truly other than the world but, far from disdaining that world, inhabits it powerfully and personally. The God who creates ex nihilo is Lord over and lover of creation. The same God who made the light and the darkness, the waters and the sky, is the one who raised Jesus from the dead, who “gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Rom. 4:17).

Beth Felker Jones is associate professor of theology at Wheaton College. This essay is adapted from her book, Practicing Christian Doctrine: An Introduction to Thinking and Living Theologically (Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2014, www.bakerpublishinggroup.com). Used by permission.

0 Comments