by Steve | Jan 10, 2023 | In the News, Jan-Feb 2023

By Thomas Lambrecht —

With the recent election of 13 new bishops, the active Council of Bishops will be made up of one-third new members on January 1, 2023. As such, they will play a powerful role in setting the direction of The United Methodist Church into the future. What do their election and the other actions of the jurisdictional conferences tell us about what that direction might be?

More Diversity. According to news reports, this group of elected bishops represents several “firsts,” recognizing the expanding ethnic diversity of the Council of Bishops. David Wilson is the first Native American bishop in the UM Church. Carlo A. Rapanut is the first Filipino American bishop. Hector A. Burgos-Nuñez is the first Hispanic/Latino bishop in the Northeastern Jurisdiction. Delores “Dee” Williamston is the first Black woman bishop in the South Central Jurisdiction. Cedrick D. Bridgeforth is the first openly gay Black male bishop. (Karen Oliveto was the first openly gay female bishop, elected in 2016.)

The diversity, however, did not extend to including one single theological traditionalist or conservative.

Expanding the “Big Tent” Leftward. Furthermore, the theological diversity of the newly elected bishops seems to run only in a more progressive direction. For example, all 13 bishops favor changing the language of the Book of Discipline defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman. They would endorse the ordination of practicing gay and lesbian pastors and support the ability of pastors to perform same-sex weddings.

In other words, the entire slate of new bishops made it clear that they all reject the United Methodist consensus on marriage and sexuality for the past 40 years of Christian “conferencing” at General Conference – including the 2019 gathering in St. Louis that was supposed to resolve our dispute.

However, the most eye-opening theological expansion was the statement by Kennetha Bigham-Tsai, from the North Central Jurisdiction, who was the first of the 13 elected. In a mystifying answer to a question, she stated, “It is not important that we agree on who Christ is. … God became flesh, but not particular flesh. There’s no particularity around that. God became incarnate in a culture, but not one culture. There is mystery and wideness and openness and diversity in who Christ is and who God is, so that every living human being has a way to touch God, to connect with God, to have a relationship with God in Christ.”

This picture brings to mind the parable of the blind men and the elephant, which originated in India centuries before Christ. In the parable, seven blind men who have never seen an elephant touch different parts of the elephant’s body (leg, tail, side, tusk) and come away with very different understandings of what an elephant is like. It seems like Bigham-Tsai is saying that Jesus Christ is different things to different people, so that each person has a way of connecting with Jesus.

It is true that Jesus meets each of us where we are in a way that opens our ability to receive him as our Savior and Lord. That is the essence of prevenient grace. However, the radical pessimism about our inability to have a unified understanding of Jesus’ basic identity is unwarranted and contrary to an orthodox understanding of Christianity.

When Jesus asked his disciples, “Who do you say I am?” Peter responded, “You are the Christ (Messiah), the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:15-16). Jesus blessed Peter for his understanding that had been revealed to him by the Father, thus affirming Peter’s statement. We ought to be able to at least have a common understanding that Jesus is the Messiah, God’s Son.

Our United Methodist doctrinal standards go into much greater detail about who Jesus is.

“The Son, who is the Word of the Father, the very and eternal God, of one substance with the Father, took man’s nature in the womb of the blessed Virgin; so that two whole and perfect natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one person, never to be divided; whereof is one Christ, very God and very Man, who truly suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, to reconcile his Father to us, and to be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for actual sins of men” (Articles of Religion, Article II)

Is Bigham-Tsai really saying that it is not important for United Methodists to agree with our doctrinal standards’ shared understanding of who Jesus is?

Given Article II’s statements, it is difficult to understand how a United Methodist bishop could state that God was not incarnate in “particular flesh.” How can it be said that “God became incarnate in a culture, but not one culture?” God was born of a virgin Jewish mother in Bethlehem at a known historical time. He lived and died as a practicing, devout Jew. His message and his life were in continuity with the Jewish Old Testament and in fulfillment of it. All of this took place within one person in one particular culture.

Yes, Jesus has relevance to every person and every culture, but God’s presence was made manifest in the particularity of one person and one culture. Without that bedrock understanding, we have no historical basis for interpreting the “Christ event” or its application to our own lives and culture.

Bigham-Tsai’s statements illustrate very well what is meant by the “big tent” approach to United Methodism. It gives the impression that United Methodist leaders do not view the doctrinal standards as actual standards, but suggestions or guidelines, to be disregarded whenever they do not “make sense” or are judged to be not helpful.

The Book of Discipline is very specific about the role of a bishop: “To lead and oversee the spiritual and temporal affairs of The United Methodist Church which confesses Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, and particularly to lead the Church in its mission of witness and service in the world. … To guard, transmit, teach, and proclaim, corporately and individually, the apostolic faith as it is expressed in Scripture and tradition, and, as they are led and endowed by the Spirit, to interpret that faith evangelically and prophetically.”

By its very nature, this “big tent” excludes traditionalists who believe there are certain doctrinal propositions that are essential to Christianity. We believe the faith defined in the Articles of Religion and Confession of Faith. Without these doctrinal understandings, we do not have Christianity, but some other religion loosely based on Christianity.

Delegates at the North Central Jurisdictional Conference were aware of these doctrinal questions regarding Bigham-Tsai, yet elected her the first bishop in this year’s class. That can be viewed either as an indifference to doctrine or the adoption of a doctrine-less United Methodism. In any case, it speaks volumes about the theological direction of the future United Methodism.

Expanded Disobedience. To great fanfare, the Western Jurisdiction elected a gay man who recently married his male partner. This election carries on the precedent the same jurisdiction set by electing Karen Oliveto as bishop in 2016, who is married to another woman. Cedric Bridgeforth was elected even though the Judicial Council ruled that Oliveto’s consecration was contrary to church law and that her standing as a clergyperson must be brought up for judicial review (it never was).

Additionally, the Northeastern Jurisdiction came close to electing as bishop another gay man married to his male partner, Jay Williams. At one point, Williams was within 20 votes of having enough to be elected.

It appears that, for many delegates, the requirements of the Discipline are to be disregarded when they do not line up with one’s ideological commitments. One episcopal candidate made the comment that change comes from the bottom up, and that rules are often disregarded by the grass roots before they are changed formally by the legislative body.

The expanded disobedience is also seen in the fact that all five jurisdictions passed a resolution that affirms a moratorium on complaints surrounding sexual orientation, asks not to pursue complaints against clergy around their sexual orientation or against pastors who officiate LGBTQIA+ weddings, and supports the election of bishops who uphold these aspirations. Questions of law were asked in at least two of the jurisdictions hoping the Judicial Council will declare the resolution null and void because it encourages disobedience to the Discipline. No matter what the Judicial Council rules, the resolution indicates the overwhelming sentiment of U.S. delegates, as well as their disregard for what the General Conference has enacted in the Discipline.

Traditionalists in the Post-Separation UM Church. Some traditionalists will unquestionably remain in the UM Church following the current spate of separations. A 2019 survey found that 44 percent of United Methodist grassroots members identified as theologically conservative or traditional. Twenty-eight percent identified as theologically centrist or moderate. Twenty percent identified as theologically liberal or progressive. Even if half of the traditionalist members leave the UM Church, those remaining would be more than one-fourth of the church’s members. Their share would still be larger than those identifying as progressive.

The question is whether traditionalists will be represented in leadership of the denomination after separation. In 2016, seven of the 15 bishops elected in the U.S. (nearly half) could be considered theologically traditionalist. (Some of those might be classified more as institutionalists than by their theological perspective, but they at least come from a traditionalist viewpoint.) In contrast, none of the 13 bishops elected now in 2022 could be considered theologically traditionalist.

Due to bishops’ retirements, seven of the 39 U.S. bishops going forward could be considered traditionalist, and even some of them would again be more institutional than traditional in their approach to leadership. At best, that means around 18 percent of the active bishops are traditionalist. If current trends continue and no new traditionalist bishops are elected, that percentage will shrink further, and traditionalists will be grossly underrepresented on the Council of Bishops.

Even more stark is the realization that nearly all the general secretaries of the general boards and agencies of the UM Church reflect a centrist or progressive theology. Traditionalists are underrepresented on the agency staffs and among the agency board members – and have been for decades. The same is true in many annual conferences when it comes to district superintendents and conference agency heads and staff.

For the foreseeable future, the traditionalist voice in the UM Church will be a minority voice and not well represented among the denominational leadership. Traditionalist members are not likely to hear their perspective communicated from bishops or general church or annual conference leaders.

Voting Strength. When the jurisdictional delegates were elected in the aftermath of the 2019 General Conference, there was a notable swing toward more progressive delegates being elected, particularly among the clergy. Since then, some of the traditionalist delegates have resigned due to their disaffiliation from the UM Church, further reducing traditionalist voting strength.

The projections made in 2019 were borne out by the vote counts at the various jurisdictions. The three resolutions passed by every jurisdiction obtained over 80 percent support in most cases. The most conservative jurisdiction is the Southeastern Jurisdiction. There, centrists and progressives made up two-thirds of the delegates.

Based on these vote counts, it is likely that the U.S. delegates to the 2024 General Conference will be at least 75 percent centrists and progressives. This would give centrists and progressives a solid majority of the conference if this year’s delegates continue to serve for General Conference.

If new delegates are elected for the 2024 General Conference, there will be a reduction in U.S. delegates and an increase in African delegates due to changing membership numbers. Unless traditionalists are completely shut out in the U.S., this shift will result in a much narrower margin for centrists and progressives. The wild card here is what would happen in annual conferences that experience high rates of disaffiliation. If those conferences, like Texas, South Georgia, and Alabama-West Florida, shift markedly toward centrist and progressive delegates, that would increase the margin and give centrists and progressives a solid majority at General Conference.

Future Directions of the UM Church. It is abundantly clear from the three resolutions passed by the five jurisdictions that the affirmation of LGBTQ+ persons and lifestyles will be a primary agenda item for the denomination. The Queer Delegates’ Resolution (the official title) affirms that each jurisdiction:

“Commits to a future of The United Methodist Church where LGBTQIA+ people will be protected, affirmed, and empowered in the life and ministry of the church in our Jurisdiction, including as laity, ordained clergy, in the episcopacy, and on boards and agencies.”

One jurisdiction held a two-hour presentation for all delegates on combatting heterosexism, which affirmed all sexual orientations and gender identities, as well as promoting the acceptance of same-gender relationships and transgender reassignment.

Another priority for the UM Church going forward will be to continue addressing the challenge of racism. Two of the jurisdictions encountered difficult circumstances around bishop elections and nomination of candidates that contributed to a perception that racism had entered into the process. One jurisdiction adjourned into executive closed session to address issues of racism connected to the conference.

The United Methodist Church is the second most white mainline Protestant denomination in the U.S. (94 percent white), following the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. Unfortunately, even a decades-long focus on representation and gender and ethnic diversity in the church’s leadership has not translated into a growing diversity at the grass roots of the church. Nevertheless, the emphasis on diversity continues. This strategy deserves rethinking.

A third priority for the UM Church will be instituting a regionalized system of governance. The Christmas Covenant proposal was overwhelmingly endorsed by all five jurisdictions. This proposal would create the U.S. part of the church as its own regional conference, along with three conferences in Africa, three in Europe, and one in the Philippines. Each regional conference would have broad powers to create its own rules and standards and adapt the Book of Discipline to fit the context and opinions of that region. The driving force behind this proposal is to allow the U.S. and Western European parts of the church to affirm LGBTQ+ relationships and lifestyles, while allowing Africa and perhaps the Philippines to maintain their more traditional understandings of marriage and sexuality. Although there may be a majority of delegates supporting this proposal, it will not have the two-thirds vote needed to pass General Conference unless the African delegates can be persuaded to support it. African leaders have previously said they could not remain in a church that endorsed same-sex relationships, even if they themselves were not forced to join in that endorsement. African delegates and members have the numbers to single-handedly block regionalization if they do not support it.

A fourth priority for the UM Church going forward will be a realignment of conference boundaries. Due to the disaffiliation of 10-20 percent of United Methodist members and churches, some annual conferences will become too small to be sustainable. There will likely be mergers and consolidation of some annual conferences. The jurisdictions recognized this reality by not filling all the vacant bishop positions. There will be seven episcopal areas with no resident bishop, with those areas being covered by nearby bishops (three in Northeast and two each in Southeast and South Central; additional vacancies will occur in North Central in 2024 due to episcopal retirements). Some annual conferences may remain intact but share a bishop with an adjacent annual conference.

There is also a working group studying the possibility of revising or eliminating the jurisdictional system altogether, which came up during floor debate in some of the jurisdictional conferences. The jurisdictions are a holdover from a racist past, having been formed in the 1939 Methodist Church merger of North and South, which also created a separate jurisdiction for Black Methodist congregations and clergy. That separate jurisdiction was eliminated in the 1968 United Methodist merger, but the regional jurisdictions remain and have fostered regional differences in the church that led to disunity. Changes to the jurisdictional system will require a two-thirds vote to amend the church’s Constitution.

Given these four priorities, two of which would entail major structural changes, it is questionable whether denominational leaders will have the bandwidth or energy to pursue essential components like evangelism, church revitalization, caring for the poor, church planting, and cross-cultural ministry. Local churches will be expected to assume primary responsibility for these areas, and they may or may not be equipped to do so.

The 2022 jurisdictional conferences provided an illuminating look at the current reality of the UM Church in the U.S., as well as some of the potential directions the denomination might take into the future. In the words of Jesus, “Anyone with ears to hear should listen and understand!” (Matthew 11:15).

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. This essay first appeared in Firebrand (firebrandmag.com) and is republished by permission. Photo: Shutterstock.

by Steve | Jan 10, 2023 | In the News, Jan-Feb 2023

By B.J. Funk —

“I don’t go to church because I know too much about those who do! They’re a bunch of hypocrites!”

How often have you heard that statement from someone who never goes to church? This seems to be the number one complaint of those who desire to remain outside. Sometimes, they even give examples of individual hypocrisy, labeling the particular sin(s) associated with a name.

What made those outside the church think that we try to get on the front row of the sanctuary, just to be seen, then afterward we sit down on ivory benches, holding our noses in the air because we think nobody is as good as us? Where did that silly nonsensical idea come from anyway?

What you are thinking is right. It comes from us. It comes from those inside the church who have never caught on to what sin and redemption is all about. It comes from the redeemed among us, as well as the smug among us. Unfortunately, we are giving the wrong image of the churched, and the unchurched are listening. And watching. And forming opinions.

So, what’s the truth about those of us inside the church?

We live inside of Revelation 3:15-16. We are neither hot nor cold. We are lukewarm and rather like it this way. That way we can stay out of arguments, away from announcing our beliefs, and remain in our comfortable pews.

We are the prodigal son from Luke, demanding our inheritance and running away from our Father’s protection.

We are Jacob cheating Esau out of his birthright and scheming with his mother to trick his father, Isaac.

We are David, wanting Bathsheba so much that he arranged for her husband to be killed in the line of duty.

We are one of the disciples, running away on that dreadful night when Jesus was betrayed. Are we Judas? Oh, surely not! Are we Thomas, doubting the reality of the resurrection?

We are just like the sinners mentioned in the Bible. We have the tendency to fall into temptation just as those outside of church. We cry when we spill our milk, we get angry when someone hurts us, we fuss with the idea of forgiveness and sometime, we gossip and – oh help us, Lord – we act like we are better than anyone else.

No wonder then. No wonder. How can we change our image? Where do we even start?

An ancient hymn, written in the 1800s by William Featherstone is a good place to start; it begins with loving Jesus and welcoming the intimate relationship he offers. It moves in the second verse to acknowledging that Jesus died for us. The third verse confesses our love for Jesus, stating I will love him in life and in death. The last verse says that I will love Jesus in the mansions in heaven and that I will continue to adore him.

“My Jesus, I love thee, I know thou art mine; For thee all the follies of sin I resign. My gracious Redeemer, my Savior art thou; If ever I loved thee, my Jesus, tis now.”

Those words make me feel safe, wanted, loved, saved. Redeemed. And completely knowing that I am his and he is mine.

In the second verse I feel I am where I belong. I am with the Master of my soul who makes arrangements to be with me. The third verse proclaims: “I’ll love thee in life, I will love thee in death.” The last verse speaks of a “glittering crown” on our brow, while the writer is exclaiming “I still love you!”

This hymn is a love song from beginning to end. And therein lies the secret to a Christian’s authentic life, the answer to our every question and the antidote for hypocrisy. LOVE. Be the love song.

B.J. Funk is Good News’ long-time devotional columnist and author of It’s A Good Day for Grace, available on Amazon.

by Steve | Jan 10, 2023 | In the News, Jan-Feb 2023

United Methodist News Service

After electing 13 new bishops during their November 2-5 meetings, the United Methodism’s five U.S. jurisdictional conferences announced episcopal assignments effective January 1.

Jurisdictional leaders recommended electing 14 new bishops; however, the Northeastern Jurisdictional Conference voted to suspend its rules and delay the election of a second bishop until the 2024 jurisdictional conference.

North Central Jurisdiction

Dakotas-Minnesota: Bishop Lanette Plambeck

Ohio East: Bishop Tracy S. Malone

Illinois Great Rivers: Bishop Frank J. Beard

Indiana: Bishop Julius C. Trimble

Iowa Area: Bishop Kennetha Bigham-Tsai

Michigan Area: Bishop David A. Bard

Northern Illinois: Bishop Dan Schwerin

Ohio West: Bishop Gregory V. Palmer

Wisconsin: Bishop Hee-Soo Jung

The North Central Jurisdiction includes the states of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin.

Northeastern Jurisdiction

Baltimore-Washington and Peninsula-Delaware: Bishop LaTrelle Easterling

Eastern Pennsylvania and Greater New Jersey: Bishop John R. Schol

New York: Bishop Thomas J. Bickerton

Susquehanna: Bishops Sandra L. Steiner Ball and Cynthia Moore-Koikoi

Upper New York: Bishop Héctor A. Burgos-Núñez

West Virginia: Bishop Sandra L. Steiner Ball

Western Pennsylvania: Bishop Cynthia Moore-Koikoi

New England: Bishop Peggy Johnson (retired)

The Northeastern Jurisdiction includes the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont and West Virginia, as well as the District of Columbia.

Western Jurisdiction

California-Nevada: Bishop Minerva Carcaño

California-Pacific: Bishop Dottie Escobedo-Frank

Desert Southwest: Bishop Carlo A. Rapanut

Greater Northwest: Bishop Cedrick Bridgeforth

Mountain Sky: Bishop Karen Oliveto

The Western Jurisdiction includes the states of Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

Southeastern Jurisdiction

Alabama-West Florida and South Georgia: Bishop David Graves

Florida: Bishop Thomas M. “Tom” Berlin

Holston and North Alabama: Bishop Debra Wallace-Padgett

Kentucky and Central Appalachian Missionary: Bishop Leonard Fairley

Mississippi: Bishop Sharma Lewis

North Carolina: Bishop Connie Mitchell Shelton

North Georgia: Bishop Robin Dease

South Carolina: Bishop L. Jonathan Holston

Tennessee-Western Kentucky: Bishop William “Bill” McAlilly

Virginia: Bishop Sue Haupert-Johnson

Western North Carolina: Bishop Kenneth Carter

The Southeastern Jurisdiction includes the states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia.

South Central Jurisdiction

Arkansas: Bishop Laura Merrill

Areas of North Texas and Central Texas: Bishop Ruben Saenz Jr.

Great Plains: Bishop David Wilson

Louisiana: Bishop Delores “Dee” Williamston

Missouri: Bishop Robert “Bob” Farr

Oklahoma, Oklahoma Indian Missionary: Bishop James G. “Jimmy” Nunn

Rio Texas: Bishop Robert C. Schnase

Texas: Bishop Cynthia Fierro Harvey

*Schnase will provide coverage for the New Mexico Conference and Nunn for the Northwest Texas Conference, as they have been doing.

The South Central Jurisdiction includes the states of Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas.

Charlotte in 2024

In November, the Commission on the General Conference announced that the 2024 United Methodist General Conference will be held April 23 – May 3, 2024, at the Charlotte Convention Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. The 2020 General Conference was set to happen in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It never took place. Instead, it was delayed for two straight years because of concerns related to the pandemic.

“The Commission selected Charlotte as the site that best met our varied needs,” said Kim Simpson, Chair of the Commission on the General Conference. The 600,000-square-foot convention center recently completed a $126.9 million expansion and is only 7 miles from the Charlotte International Airport and within walking distance of 200 restaurants.

Delegates from Africa, Europe, Asia and the U.S. will attend the 11-day gathering, which is expected to attract about 5,500-7,500 people.

PHOTO: Newly elected bishops, the Rev. Delores Williamston (left), the Rev. Laura Merrill, and the Rev. David Wilson stand during their consecration service at the South Central Jurisdiction. UM New photo courtesy of the Louisiana Conference via Facebook.

by Steve | Jan 10, 2023 | In the News, Jan-Feb 2023

By Terry Teykl —

Paul wrote in I Thessalonians 5:17 “pray without ceasing” or “pray continually.” This verse has inspired so many over the years to set a goal of unceasing prayer – individually and as a team, like tag-team prayer. It has head waters in the upper room in Acts 1: 14: “They all joined together constantly in prayer, along with the women and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with his brothers.” Thus began the 24-7 movement of praying the price, and Pentecost followed. Ever since, this audacious and powerful prayer practice has been in place and thriving.

The Early Monastic Tradition of Continuous Prayer. The 24-7 prayer was most evident in the Monastic tradition. For over one thousand years, monasticism (the practice of taking vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to one’s spiritual superior) has held a key role in developing theology and training on prayer. From the fourth and fifth centuries, monks and nuns were an accepted part of society. Monasticism was the cradle in which continuous prayer spread. Some of the key figures from this tradition are Alexander Akimetes and The Sleepless Ones.

Educated in Constantinople, Alexander was an officer in the Roman army. Motivated by Jesus’ words to the rich young ruler from Matthew 19:21, Alexander sold his possessions and retreated to the desert. Tradition states that he set fire to a pagan temple after seven years of solitude. Upon arrest and imprisonment, Alexander converted the prison governor and his household and promptly returned to his abode in the desert.

Shortly after that, he had the misfortune to fall in with a group of robbers. His evangelistic zeal could not be contained, and he converted these outcasts into devoted followers of Jesus. This group became the core of his band of monks. The monks were watching with God because he watches over us 24 hours a day (Psalm 121) and calls us to watch and pray with him. Revelation 4-5 states that the angels and the 24 elders worship God literally night-and-day. The Bible teaches us to pray that God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven, and in heaven there is only praise, worship, and intercession, 24 hours a day. This is why it is believed then and now that praise, worship, and intercession should also take place on earth. The only way in which this can be realized is by establishing 24-hour prayer watches. For example, Alexander’s followers – The Sleepless Ones – were divided into six choirs rotating throughout the day, each new choir relieving the one before to create uninterrupted prayer and worship 24 hours a day.

Legacy of prayer. “The Moravian Community in Herrnhut in Saxony, in 1727, commenced around-the-clock ‘prayer watch’ that continued nonstop for over a hundred years,” wrote the Rev. Leslie K. Tarr in Decision. “By 1791, 65 years after commencement of that prayer vigil, the small Moravian community had sent 300 missionaries to the ends of the earth.”

Professor Tarr went on to ask: “Could it be that there is some relationship between those two facts? Is fervent intercession a basic component in world evangelism? The answer to both questions is surely an unqualified ‘yes.’”

Early in his life, John Wesley visited the Moravian prayer revival and was deeply influenced. The DNA of our Methodist movement has roots in the Moravian 100-year 24-7 prayer movement.

Continuous Prayer in the 20th Century. On September 19, 1999, the International House of Prayer in Kansas City, Missouri, started a prayer and worship meeting that has continued around-the-clock ever since. With a similar vision to the Moravians – the fire on the altar should never go out – there has never been a time when worship and prayer have not ascended to heaven since that date. The founder of this prayer-worship movement is Mike Bickle.

The IHOP-KC prayer room is a sanctuary of corporate worship and intercession, staffed by prayer leaders, singers, musicians, and worship leaders who serve as missionaries. They offer a 24-7 web stream into their prayer room so that people can connect long distances at any time, no matter where they find themselves. Stream on whatever device you wish free of charge. In addition to English, it is now also streamed in nine different languages via their All Nations Prayer Meeting.

At the same time, in many other places around the world, God has placed desires and plans for 24-7 prayer in the fabric of diverse ministries and in the hearts of leaders. Their effects have resulted in 24-7 houses of prayer and prayer mountains being established in every continent of the earth.

Boiler Room. Also in 1999, Pete Greig founded the Boiler Room Prayer Movement. It is an international, interdenominational movement of prayer, mission, and justice that has been praying night-and-day for more than 20 years and has reached more than half the nations on earth. It is an attempt to create modern urban monasticism. He’s written a book about the history of the 24-7 prayer called Red Moon Rising. The original Boiler Room was in Reading, just west of London. The name Boiler Room came from Charles Spurgeon, who called his prayer room by that name. When he preached, 200 people were praying under the sanctuary in the boiler room.

A well-known “Boiler Room” in Canada is found in Calgary. It was the first 24-7 model that launched outside of the U.K. They have intentionally called it Urban Monastery Calgary. It is a constant site for strategic prayer information for Canada and the world. The ultimate goal of the Boiler Room ministry is to replicate the communal life found in the monasteries. A 24-7 Boiler Room is a simple Christian community that practices a daily rhythm of prayer, study, and celebration while caring actively for the poor and the lost. Boiler Rooms exist to love God in prayer and to love its neighbors in practice.

Across the globe, there are thousands of places hosting 24-7 prayer and worship. For example, there are more than 250 different Houses of Prayer (all 24-7) in Indonesia. In Java, there is a three-story house of prayer with 45 rooms set aside for prayer, in addition to 20 bamboo huts in the Prayer Garden surrounding the main house.

The Korean Prayer Stronghold. The Korean church leads the way in marinating prayer. I did some research in Korea while working on my doctorate. I was stunned and impressed by their commitment to pray early in the morning, the amount of time they dedicate to prayer in their worship services, prayer in cell groups, and the 100 or more well-used prayer mountains scattered across the country. I think there are four reasons for such a passion for prayer.

First, their love and reverence for the Lord Jesus. Their prayer is a love exchange with God. They take seriously the biblical mandate to pray without ceasing. Plus, they are a dependent culture. To ask them to depend on God is like asking a teenager to eat, whereas in America we are an independent culture. We do not want to depend on anyone – much less God for anything.

Second, the impetus as a regular spiritual discipline came in part from the time when Japan colonized the Korean peninsula, and the Korean people had no recourse except prayer for the freedom of their people. They experienced a lot of pain and suffering during this time. Prayer was a powerful response.

Third, they had a spiritual awakening in 1907 in Pyongyang, Korea. Dawn prayer meetings now are a response to this major spiritual awakening. Every church has early morning prayer seven days a week.

Fourth, they pray out of desperation. All the guns on the border of North Korea are pointed at South Korea. North Korea poses an ongoing threat to their way of life. They could be attacked at any time. They depend on God to protect them. I personally saw this when I went to Osanri Choi Jasil Memorial Fasting Prayer Mountain in Korea. There is a hotel there for people who go there for a week to pray. During my time in Korea, I was struck by the naturalness and normalcy of continual, constant prayer.

The Prayer Room Movement. In 1985, I wrote a book called Making Room to Pray about building a prayer room in a local church. Hundreds of churches signed their members up to pray around the clock. These prayer rooms provide a “warm center” like a centrifuge to spin off so many fruitful ministries. A pastor can sleep well knowing that there is someone praying at the church all during the night.

The Benefits of Continuous Prayer. One, a 24-7 prayer watch will be one way a church can fulfill God’s command to be a house of prayer for the nations (Isaiah 56:7). By implementing 24-7 prayer watches, churches can take responsibility and stand as watchmen on the walls for the church worldwide, for their own communities, their country, and for other nations.

Two, around-the-clock praise, worship, and intercession bring about a new and deeper dimension with regard to an intercessor’s relationship with God.

Three, a continuous prayer watch focuses on bringing in the harvest. Prayer is not an end in itself. Prayer brings us into fellowship with God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit. When we start to fellowship with Jesus, he will reveal his heart to us and take us to people in need. The purpose of prayer is to strengthen us to live the Great Commandment (to love…) and the Great Commission (to go…). We do not pray for the sake of praying. Real prayer will always lead to action: touching people’s lives with the love and compassion of Christ.

Four, through prayer watches we can pray night-and-day for our own needs and the needs of the community. Night-and-day prayer helps us to persevere in prayer, to continue in prayer, and to pray continually as the Word commands us to do.

Five, a 24-hour prayer watch promotes unity among believers because they focus on the same issues and pray together for them. It also binds churches and denominations together. In Katy, Texas, more than 25 churches take turns by taking an hour of prayer and worship at the Southwest Prayer Center.

Six, it helps every intercessor and prayer group to understand that they have a Kingdom responsibility, and it strengthens them to know they are not praying alone, which is for most people a huge encouragement.

Seven, history shows that night-and-day prayer had a huge impact on communities and on the world.

Jesus says that the Father rewards the prayers of those who seek him. We should seek his heart, have a relationship with him, and pray for him to move in our lives and church. Scripture says, “Yet he [Jesus] often withdrew to deserted places and prayed” (Luke 5:16). If we desire to follow in Jesus’ footsteps, this is a good place to begin.

Terry Teykl is a United Methodist clergyperson who has devoted his life and ministry to prayer. He is also the author of numerous books, including Pray the Price, Blueprint for the House of Prayer, and Making Room to Pray. This essay is adapted from his new book Chronicles of Prayer: Praying in Jesus name for 21 centuries (PrayerPointPress.com).

by Steve | Jan 6, 2023 | In the News, Jan-Feb 2023, Uncategorized

By Steve Beard —

Dublin was still rubbing sleep from its eyes. It was the crack of dawn. Well, not literally – it just seemed that way. The sidewalks along historic statue-lined O’Connell Street were largely empty as I paced toward Trinity College on the south side of the Liffey River. In just hours, tourists would once again be shoulder to shoulder up and down the popular thoroughfare.

But for the moment, it was a crisp and peaceful morning. For a city known for its literary superstars such as James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, and Seamus Heaney, the most celebrated and valuable book in town is a Latin text created around 800 A.D. by a team of obscure monks on a tiny wind-whipped island 200 miles north of the Irish capital. This was my opportunity to see the mysterious and captivating book.

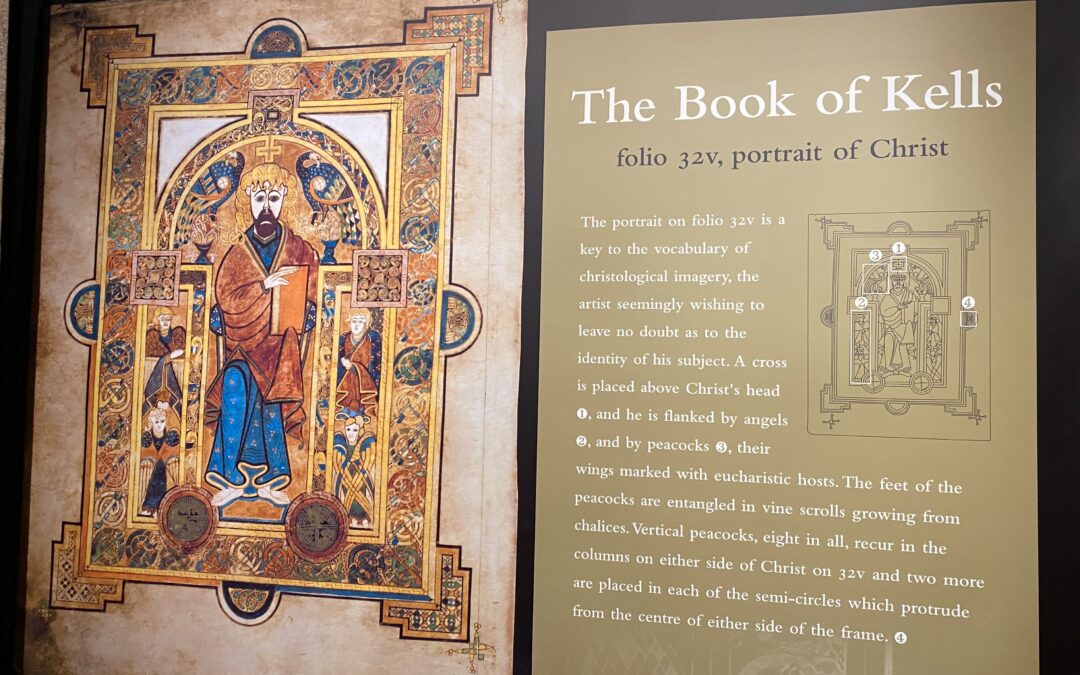

Believed to have been developed in a monastery on the island of Iona off the coast of Scotland, the Book of Kells is a 1,200 year old “illuminated manuscript” of the Four Gospels of the New Testament. “You can imagine the monks inside their beehive-shaped stone huts, battered by sea winds with squawking gulls outside, bent over their painstaking work,” observed Martha Kearney, a British-Irish journalist, for the BBC.

Within historical context, Johannes Gutenberg would not create the printing press for another six centuries. The mere existence of the Book of Kells is remarkable.

Surviving an assortment of vicious Viking raids on Iona, the sacred text was moved to the monastery of Kells in County Meath, northwest of Dublin. The magnificent volume measures 13 x 10 inches and contains 340 folios (thus 680 pages) made of calfskin vellum. The collected manuscript – created by a team of scribes and artists – was eventually sent to Dublin for safe keeping at Trinity College in 1661.

There is kind of a bittersweet irony that the elegant scribes of the world-famous Book of Kells are known simply as Hand A, Hand B, Hand C, and Hand D. The artistic collaborators – probably three – produce portraits and scenes that are simply otherworldly. Some of the mind-boggling precision can only be fully appreciated with a magnifying glass.

Weeks prior, I had signed up with a private early morning lecture group to learn more about the treasured medieval book. It was also a crass move on my part to skip the legendarily lengthy lines to see the masterpiece. One couple in my group was from Hawaii, another from Texas, still yet another family was from Italy. We joined millions of previous tourists that have filed past the heavily-secured manuscript in order to be within close proximity of such an utterly unique combination of sacred text and enigmatic art.

More than a thousand years ago, it was described in The Annals of Ulster as the “chief relic of the western world.” It was also reported that it had been stolen from Kells in 1006 and later discovered – without its richly bejeweled cover – and possibly buried under ground.

Today, the same engineers who designed the protective cases for the Crown Jewels and the Mona Lisa were assigned to the Book of Kells. In his book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, Christopher de Hamel reports that the security surrounding the Book of Kells is “as complex as presidential protection undertaken by the secret services of a great nation.” In order for him to view the manuscript personally, he sat at a “circular green-topped table, prepared in advance with foam pads, a digital thermometer, and white gloves.”

He was granted truly privileged access. Nevertheless, to those without the white gloves, the luster of the treasure still shines through as a testimonial to faith, devotion, and imagination. The sacred and exotic art includes the first full-page portrait of the virgin Mary and Jesus in western manuscripts, intertwining snakes, eucharistic chalices, intricate knotwork, a stunning Chi-Rho (Greek monogram for the name of Christ), vivacious peacocks, tightly coiled spirals, knotted ribbons, Christ tempted by the devil, and a portrayal of the gospel evangelists as the “four living creatures” (a tetramorph): Matthew as the man, Mark as the lion, Luke as the ox, and John as the eagle.

The colorful palette includes black, red, lilac, pink, purple, and yellow ink.

The 12th century historian Gerald of Wales is assumed to have been describing the Book of Kells when he wrote: “Fine craftsmanship is all about you, but you might not notice it. Look more keenly at it and you will penetrate to the very shrine of art. You will make out intricacies – so delicate and subtle, so exact and compact, so full of knots and links, with colours so fresh and vivid – that you might say that all this was the work of an angel, and not of a man.”

Even modern day scholars have a hard time hiding their astonishment. “The writing, in huge insular majuscule script, is flawless in its regularity and utter control,” writes de Hamel, an expert on medieval manuscripts. “One can only marvel at the penmanship. It is calligraphic and as exact as printing, and yet it flows and shapes itself into the space available. It sometimes swells and seems to take breath at the ends of lines. The decoration is more extensive and more overwhelming than one could possibly imagine. Virtually every line is embellished with color or ornament.”

We will never know the names of these saints of quill and ink with a mindfulness for bewildering detail, righteous pizzazz, and fantastical beasts. The ancient Scripture teaches that we are “surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses.” In that number are the artists and scribes who painstakingly stretched their imaginations and devotion to create the Book of Kells. To those saints, with all gratitude, thank you.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Steve | Jan 4, 2023 | Home Page Hero Slider, In the News, Jan-Feb 2023

By Kimberly Constant —

Ezekiel stood, looking out across a valley filled with bones that stretched as far as he could see. Bones that were brittle. Bleached by the relentless sun and worn down by the ravages of time. Bones which represented the once proud nation of Israel, now seemingly without hope. Devastating reminders of what had been a community of God’s own formation, tasked to make his glory known. Now bearing silent witness to the devastating reality of the downfall of God’s covenant people because of their sin. As Ezekiel surveyed the wreckage, with God at his side, God posed a weighty question, “Son of man, can these bones live?”

Can these bones live? Perhaps it’s a question that we find ourselves pondering. As a new year dawns, it is natural for many of us to think about fresh starts. New beginnings. To look with expectant hope to a future in which we long to find better days. But sometimes, we face more of the same seemingly endless challenges of the past. Illness, debt, broken relationships, dwindling faith, all of which have us staring into our own valley of bones. Perhaps, mourning the loss of what once was, we look into a new year filled with terrifying unknowns and wonder if there are some situations which might be beyond hope. Maybe in this season of fresh starts and new beginnings some of us wonder if revival is possible. Can God really breathe new life into something that seems as far beyond the point of resuscitation as a valley filled with bones?

In reading Ezekiel’s vision, recounted to us in chapter 37 of the biblical book that bears his name, we might ask why Ezekiel himself didn’t pose this question to God, instead of the other way around. Didn’t Ezekiel wonder? Surely, as one of God’s prophets he knew the words of those who preceded him, which spoke to the promise of rebirth. That the exile of God’s people, both a physical separation from the land of promise and a spiritual separation from the God of promises, would not last forever. At least for a remnant. Could it be that the thought did not enter his mind? Maybe as Ezekiel looked out across that valley of death, what lay before him seemed like a heartbreaking indication that indeed all hope was lost for the majority of Israel. That if a remnant would arise, certainly it would not be from this pile of death.

So, in the silence of the moment, as God and Ezekiel took in the sorrow and despair of that valley of bones, God asked the question that Ezekiel either couldn’t or wouldn’t ask. A question for which only God could supply the answer. Ezekiel said as much, “My Lord God, you know.” Some translations insert a word of emphasis, “My Lord God, you alone know.” Can these bones live? You tell me, God. For any answer in the affirmative would require a miracle that only you can provide.

But the truth is that God had been asking and answering that question since the formation of our world. Marshalling out of nothing a universe of such brilliance and complexity that scientists and poets through the ages have found no shortage of material for exploration and invocation. Forming and fashioning that universe through the power of his voice; his words constructing light and space and time. Creatures and environments and the pinnacle of it all, us.

God had asked and answered this question over and over again. In his provision of coverings for the shame and sin of Adam and Eve in the garden. In the olive branch delivered by the dove to Noah as he waited for the waters to recede. In the words of Joseph to his brothers upon their discovery that he had not just survived their cruel actions but had become their means of salvation from a vicious famine, “What you meant for evil, God meant for good.” God asked and answered this question when he brought the people out from slavery in Egypt. When he assembled them at the foot of Mt. Sinai and formed them into a nation bound to him by a covenant of holiness. And later when they complained. When they worshipped the golden calf. When they bought into the fear in the eyes of ten of the spies returning from their scouting mission in Canaan. God asked and answered this question when he brought down the walls of Jericho yet brought out from the destruction the Canaanite prostitute Rahab and her family as a reward for her courageous faith.

God asked and answered this question for Ruth and Naomi when they had lost everything. For David in the wilderness as he fled from Saul. For Elijah as he prayed for death to relieve his loneliness and pain. For Mordecai and Esther as they faced the eradication of their people. God asked and answered this question for the nation of Israel each time it assembled itself to renew the covenant, repentant for the sin of the past and expectant for a future of obedient faithfulness. God asked and answered this question through the promises of his prophets. That indeed restoration would follow judgement. Indeed, hope need not die even in the face of terrible suffering. For not only would a remnant return to rebuild a devastated Jerusalem, but God would also send a righteous ruler. A king, a prophet, a priest to usher in a new beginning. To restore what had been lost. Not just for Israel. But for all. And although Ezekiel could not see nor understand the implications of some of these prophecies, we know that God asked and answered this question once and for all from a cross and an empty tomb and a throne seated at his right hand.

Can these bones live? The answer is always yes for those who cry out to God. God’s grace and mercy remain an ever-present gift for us, ready to be received at any moment, not just at the turn of a new year. Ours for the taking if we will repent. If we will turn from pursuing our own will and desires and turn towards the path of God. God asked Ezekiel the question not because God needed him to supply the answer. God wanted Ezekiel to be part of the solution. To serve as God’s mouthpiece once more and to prophesy to those dead people. Ezekiel had a part to play in reviving what seemed forever lost.

So, God said, “Prophesy. Tell these bones to hear my word. They will live. And they will know that I am the Lord.” Ezekiel, to his credit, didn’t run away in terror or laugh in utter incredulity. He didn’t question his abilities or ask God to send someone else. Ezekiel spoke to that pile of death and God breathed life into the broken remnants of his people. What arose was something truly magnificent, an exceedingly great army. Warriors strengthened and brought to life by God. The hope of Israel renewed and restored from the grave of its demise.

Many of us might feel as if we, too, are staring into an abyss of bones. The remnants of our own hopes and dreams. The remains of marriages, friendships, jobs, even of our churches, many of which have experienced something akin to divorce in this last year. Many of us might feel as if we’ve lost our moorings. As the secular world increasingly dismantles any notion of fundamental morality, we might feel as if our way of life is becoming more and more of a fringe movement. Perhaps we’ve endured scorn and ridicule, even cancellation, for the beliefs that define us as Christians. As the people of God perhaps we wonder where do we go now? Can God still breathe new life when and where it seems impossible?

God stands beside us and poses the very same question he asked of Ezekiel, “People of God, can these bones live?” Even as we ask ourselves, can we find our way forward through a world filled with so much anger and pain? Can we find our way forward through the disdain of society that wants nothing to do with God, let alone an understanding of moral and ethical absolutes? Can we find our way forward in new or changing denominations? Can we as God’s people find our way forward through the valley of bones that lay before us?

To that God says, prophesy. Speak to the bones. Prophesy to the breath. Proclaim the truth. The hope and the life available through Jesus Christ. The peace and comfort to be found in the Gospel. Speak of the love of God so great that there is nothing that can separate us from that love. Not even death. And then, and then my friends, we will live.

The story of the Bible is a story book-ended by beginnings. From the beginning of our universe and our creation as human beings, born from the dust of the earth, imprinted with the image of God, and imbued with his life-giving and sustaining breath. To the beginning of a new creation, at the end of days, when we will live in the very presence of God in resurrection bodies that testify to God’s ability to revive and restore. In fact, the story of the Bible is one of continual beginnings arising from what looked like endings. It’s a story of hundreds of fresh starts. Made possible because we are loved by a God whose power is limitless.

But it is a story that needs telling. God calls each of us to play a part in spreading the hope of new beginnings. We as God’s people must be willing to speak God’s word into the darkest corners of the world. Into places where it looks as if there is no one to hear; no one who cares. Even if they laugh. Even if they scream. Even if they threaten. Even if they do their worst. Prophesy. Speak to the breath of the one who can do the impossible. For from the disasters of the present, God can and will call forth his people into a time of greater unity, a time of resolute purpose. Not just a people, but an army of spiritual warriors. Where we might see nothing but old bones, a hopeless wasteland, painful endings, God envisions a fresh explosion of life.

As we march into 2023 let us remember that sometimes what comes from brokenness is even more beautiful than that which came before. From Jesus’s birth came his ministry, from his ministry came the cross, from the cross came the empty tomb, from the empty tomb a throne. Indeed, because of Jesus’ victory, we can endure. Indeed, we will live.

Kimberly Constant is a Bible teacher, author, and ordained elder in the United Methodist Church. You can find out more about Rev. Constant at kimberlyconstantministries.com.

Art: Francisco Collantes (1599-1656). Vision of Ezekiel. Public domain.