by Steve | Oct 5, 2020 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Thomas Lambrecht –

Ecce homo by Antonio Ciseri.

“What is truth?” Pontius Pilate asked that compelling question during his interrogation of Jesus prior to condemning him to the cross (John 18:38). For Pilate, that question was a cry of despair — he had given up on ever finding the answer.

It appears that many Americans, including many American Christians, also despair of ever finding truth. A recent survey conducted by the Cultural Research Center at Arizona Christian University under the direction of Dr. George Barna found that a majority of Americans no longer subscribe to a historic understanding of what “truth” is.

The survey found that 58 percent of Americans agreed that “Identifying moral truth is up to each individual; there are no moral absolutes that apply to every person, all the time.”

Let that sink in a moment. Nearly six out of ten Americans think they can make up their own moral truth. That means the Ten Commandments (honor your father and mother, do not lie, do not steal, do not murder, do not commit adultery) are merely suggestions. That means that some people might be perfectly entitled to believe that theft, murder, rape, or racism is acceptable, according to their own personal truth.

According to the survey, the only group in society that did not have a majority holding this opinion was evangelical, born-again Christians. Yet a strong minority (46-48 percent) of these Christians agreed with the “personal truth” idea. Somewhat encouragingly, only 33 percent of committed Christian leaders agreed that there is no absolute moral truth.

Basis of Truth

When asked, “What is the basis of truth,” the most common answer was God. Yet only 42 percent of Americans referenced God as the basis of truth. Another 16 percent found truth in “inner certainty,” while 15 percent look to “scientific proof.” (One wonders how science could ever be a determining factor for moral truth. What scientific study could prove that lying or adultery or racism is morally wrong?) Smaller percentages rely on tradition (5 percent) or public consensus (4 percent) to determine moral truth.

Among Christians, seven out of ten evangelicals, Pentecostals, and born-again Christians picked God as the basis of truth. Again, 87 percent of committed Christian leaders chose God. But among Catholics, only 43 percent saw God as the basis of truth, and only 37 percent of Mainline Protestants did so.

Adults under age 30 were less likely to select God as the basis of truth – 31 percent, compared to 45 percent among older adults. Southern states gave God slightly more recognition (48 percent), compared to an average of 38 percent for other regions of the country.

Implications

The idea that there is no absolute truth is part of the philosophy known as post-modernism. Based on the survey results, it appears that a strong majority of Americans operate out of a post-modern mindset.

This highly individual approach makes agreement about anything much more difficult. Since there is no one agreed-upon standard for moral truth, we hold nothing in common, to which we can all appeal to settle disputes. I might point to a biblical teaching or to a particular secular law, but you could come back with, “That is your truth, but I don’t accept it as my truth.” The argument is at a stalemate. There is no way to resolve it. This is a contributing factor to the gridlock and endless conflict in our society and government today.

Just from a rational perspective, post-modernism gives us no basis upon which to critique another person’s moral beliefs or actions, since everyone has their own, self-made moral framework. It all boils down to self-interest. Something is wrong if it hurts me. But there is no objective standard by which society can judge what you did to be wrong. What a mess!

A Christian Understanding of Truth

Fortunately, Christians do have a moral framework that applies in all times and places, based on the reality of God and his teachings found in Scripture.

Jesus said, “I am the way and the truth and the life” (John 14:6). “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth” and “the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ” (John 1:14, 17). Jesus said, “If you hold to my teaching, you are really my disciples. Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (John 8:31-32). The Holy Spirit is called the “Spirit of truth” (John 16:13).

We are not only called to know the truth, but to live by the truth. “But whoever lives by the truth comes into the light, so that it may be seen plainly that what he has done has been done through God” (John 3:21). “Yet a time is coming and has now come when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for they are the kind of worshipers the Father seeks. God is spirit, and his worshipers must worship in spirit and truth” (John 4:23-24). Jesus prayed for us, “Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth” (John 17:17).

The psalmist prays, “Show me your ways, O Lord, teach me your paths; guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are God my Savior, and my hope is in you all day long” (Psalm 25:4-5). “Test me, O Lord, and try me, examine my heart and my mind; for your love is ever before me, and I walk continually in your truth” (Psalm 26:2-3). “‘These are the things you are to do: Speak the truth to each other and render true and sound judgement in your courts; do not plot evil against your neighbor, and do not love to swear falsely. I hate all this,’ declares the Lord” (Zechariah 8:16-17).

One of the signs of Israel’s downfall was its abandonment of truth. “So justice is driven back, and righteousness stands at a distance; truth has stumbled in the streets, honesty cannot enter. Truth is nowhere to be found, and whoever shuns evil becomes a prey” (Isaiah 59:14-15). “Go up and down the streets of Jerusalem, look around and consider, search through her squares. If you can find but one person who deals honestly and seeks the truth, I will forgive this city'” (Jeremiah 5:1).

God promises truth as one of the blessings of his presence. “This is what the Lord says: ‘I will return to Zion and dwell in Jerusalem. Then Jerusalem will be called the City of Truth'” (Zechariah 8:3).

We can try to ignore the truth, but that is like ignoring gravity — gravity (and truth) wins every time! We can pretend to make up our own moral truth, but that puts us in the place of God. Are we really prepared and equipped to be God, even just for our own lives? Trying to be our own god is the height of human hubris. When God sees us try to usurp his place, he laughs (sarcastically). It must be incredibly sad for God to see us puny creatures attempt the impossible and in the process ruin our lives and our world.

That is why God spoke the truth through his Word and sent Jesus, the living truth, into his world to teach us the truth. It is only through God’s truth being actualized in our lives that we can be the person God created us to be. Surrendering to his truth is the only way out of the darkness and into the light, the only way to true freedom.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Sep 28, 2020 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

Making Moral Choices

By Thomas Lambrecht –

Over the last two weeks, we have looked at results from a recent survey conducted by the Cultural Research Center at Arizona Christian University under the direction of Dr. George Barna. We saw that many Americans are confused about who God is and what God is like. We also found that many Americans and even Christians believe in salvation through being or doing good.

But what does it mean to be good or to do the right thing? This enters the realm of making moral choices. These choices begin with a basic concept of what is a human being, and what is the value of human life.

The Value of Human Life

According to the survey report, 56 percent of Americans believes that human beings are created by God and made in his image, but are fallen and in need of redemption. At the same time, 69 percent believe that “people are basically good.” This is another example of confusion on the part of presumably 13 percent who believe that human beings are at the same time “fallen and in need of redemption” and “basically good.” (This is actually a decline from the 83 percent who thought “people are basically good” in 1990 — a testament to our more pessimistic current time.) I wish the survey report had separated the question of whether human beings are created by God and made in his image from the question of whether they are fallen and in need of redemption. That would give us a better understanding of how people value human life. Some may believe that humans are created by God in his image but are not fallen and in need of redemption.

That question of the value of human life is answered rather starkly in another question, where only 39 percent of Americans said “human life is sacred.” Even for evangelical Christians and political conservatives, only 57 to 60 percent agreed with the sacred value of human life. Other views on life included the 37 percent who believe “life is what you make it, but it has no absolute value” and the 11 percent who believe “life does not attain its full value until we reach our highest point of evolution and expression.” This contingent view on the value of human life could help explain the travesty of more than two-thirds of Down syndrome babies being aborted before birth. If human life has no absolute value or is not valuable until it has reached some developmental maturity point, then such abortions can be morally justified, as can many other actions that demean or threaten human life and dignity.

Moving more specifically to the question of abortion, 37 percent of Americans say the Bible is ambiguous on abortion and an additional 22 percent say they do not know. This means only 41 percent believe the Bible is clear in teaching the sacred value of human life in the womb.

One’s concept of the value of human life is the grounding point from which many other ethical decisions flow. Hatred, the culture of insult, discrimination, violence, racism, and many other harmful attitudes stem from our unwillingness to value the other person as created in the image of God and of sacred worth. One of the greatest contributions of Christianity to Western civilization over the centuries has been the concept that even the most disregarded or poorest human being was of infinite value to God. While not always practiced, this understanding of human life has led to many advances, compared to the brutality evident in many pre-Christian civilizations. Yet today we are in danger of losing this foundational understanding.

Source of Moral Guidance

Where do we turn for guidance in making moral decisions? The survey reported that only one-third of Americans turn to a religious source for moral guidance. Twenty-three percent turn to the Bible, six percent look to direct divine intervention, and three percent rely on the input of religious leaders. Encouragingly, about two-thirds of evangelical Christians turn to these religious sources.

Another third (31 percent) of Americans looks to themselves when making moral decisions. A third group (27 percent) relies on trusted people for help, mainly family, friends, and peers.

This heavy reliance on self and other people to guide moral decision-making may account for why so often Christians act just like the society in which they live. It is the Bible and the historic teachings of our church that help us live by a value system that often contradicts that of our society. Our most valuable testimony is that we live differently from those who do not follow Jesus. That testimony is lost when we fail to use the resources of our faith in making moral decisions. At the same time, the Christian veneer that has generally sustained Christian values in secular American society in the past is swiftly eroding.

Practical Morality

The survey set forth several scenarios and asked respondents to register their moral opinion. Six out of ten Americans (and 83 percent of committed Christians) stated that the intentional failure to repay a loan to a relative is morally unacceptable.

Less than half of Americans (47 percent), and in contrast, 75 percent of committed Christians, thought that telling a minor lie to protect one’s personal best interests or reputation is morally unacceptable.

As might be expected, abortion was the most divisive issue in the survey. Forty-four percent of all Americans thought that having an abortion because the woman’s partner has left and the woman cannot reasonably take care of the child is morally unacceptable. Twenty-two percent believe it is morally acceptable and eleven percent think it is not a moral issue. (One-quarter do not have an opinion.) As expected, 83 percent of committed Christians believe such an abortion is morally unacceptable.

Only one-fourth (27 percent) of all Americans think having sexual relations with someone that they love and expect to marry in the future is morally unacceptable. In contrast, 71 percent of committed Christians believe it is morally unacceptable. This result was the widest gap between Christian moral decisions and those of the general population.

Implications

The practical questions actually give mildly encouraging results, in that they showed committed Christians maintained a dramatically more traditionally Christian value system. (The survey defined committed Christians as those who were spiritually active and involved in church leadership.) Regular members were often less affirming of traditional Christian values in their decisions.

This survey shows that it will be important for Christian pastors and leaders to teach the foundations of Christian moral reasoning, starting with a solid understanding of the sacredness of human life and its implications for how we are to treat one another. This understanding can transform the way our society functions, especially in such a time of polarization and division.

It will also be important to teach our people how to look to the teachings of Scripture and the historic teachings of the church to find moral guidance for everyday life. We need to make these teachings understandable and accessible to all Christians in a way that will influence their everyday lives. Teaching on particular moral issues helps, but it is more important to teach our people how to think Christianly about moral issues and enable them to make good decisions without necessarily being told what to do in every situation. While teaching on abortion and human sexuality is important, we need to broaden our teaching to other moral arenas, such as human relationships and financial integrity.

The old song says, “They will know we are Christians by our love.” When people observe how Christians live, they should see a distinctive difference from the self-centered values of the world. The survey results show we have room for improvement in learning how to live as Christians in an alien world.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Sep 21, 2020 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

Michelangelo (God creating Adam)

By Thomas Lambrecht –

What is God like? That seems to be the most fundamental question any religion has to answer. Each religion has their own answer to that question, which in turn makes each religion distinctive.

Christianity has a particular answer to that question that has been taught and believed for over 3,000 years of Judeo-Christian faith. We believe in a personal God who is the “all-powerful, all-knowing, perfect and just creator of the universe who still rules the world today.” That description is from the recent survey conducted by the Cultural Research Center at Arizona Christian University under the direction of Dr. George Barna.

Strikingly, the survey found that only 51 percent of Americans believe the Christian definition of God. This is down from 73 percent in 1991. The result points to the steady erosion of the Christian worldview from American society over the past 30 years.

Twenty-six percent are either agnostic (“a higher power may exist, but nobody knows for certain”) or simply don’t know what to think about the notion of God. Ten percent hold a “New Age” view, claiming that “God refers to the total realization of personal, human potential or a state of higher consciousness that a person may reach.” Seven percent hold a polytheistic (“there are many gods”) or pantheistic (“everyone is god”) view. Amazingly, only six percent claim to be atheists (“there is no such thing as God”).

The good news is that 94 percent of Americans believe in some sort of god, or at least the possibility that God exists. The downside is that opinions about God are all over the map and quite confused. Even as many as 20-30 percent of those claiming to be Christians are either not sure whether God exists or have a non-Christian view of God.

The survey found that 71 percent of Americans say they “have no doubt that God loves you unconditionally.” That means that 20 percent who are either unsure about God’s existence or have a non-Christian understanding of God nevertheless believe God loves them.

Only one-third of the public believe that it is possible to be certain about the existence of God, while 57 percent feel “it is impossible to be certain about the existence of God; it is solely a matter of faith.” In a further example of inconsistency, 66 percent believe “God has a reason for everything that happens” to them. And of the 51 percent who hold a Christian view of God, only one-third believe that God is involved in their lives.

Combining a number of questions about God, only ten percent of the American public have a robustly Christian view of God. They believe he is all-powerful, all-knowing, perfect, the just creator of the universe, that he still rules it today, that he loves the person unconditionally, that he has a reason for everything that happens in a person’s life, and that he is involved in the person’s life. Yet that is what the Bible teaches us about God. Apparently, most do not completely accept those teachings.

Who Is Jesus? Satan? The Holy Spirit?

Christians believe that Jesus is God, the second person of the Trinity, while at the same time human. Fully 85 percent of Americans get that Jesus is fully divine and at the same time fully human. However, 44 percent believe that Jesus “committed sins, like other people.” Only 41 percent accept the biblical testimony that Jesus was without sin. Hebrews reminds us, “Therefore, since we have a great high priest who has gone through the heavens, Jesus the Son of God, let us hold firmly to the faith we profess. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are — yet was without sin. Let us then approach the throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help us in our time of need” (4:14-16). Paul affirms, “God made him [Jesus] who had no sin to be sin [or a sin offering] for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21). It was Jesus’ very sinlessness that qualified him to be the “lamb without blemish,” the perfect offering for the forgiveness of our sins.

Meanwhile, Americans appear more confident in the existence of Satan than they are in the existence of God. While only 51 percent believe in the existence of a God who is at work in the world today, 56 percent believe that “Satan is not merely a symbol of evil but is a real spiritual being and influences human lives.”

Christians believe that the Holy Spirit is a spiritual being who is God, the third person of the Trinity. Only one-third of Americans agree. Over half (52 percent) contend that “the Holy Spirit is not a living entity but is a symbol of God’s power, presence, or purity.” Yet, on the night before he died, Jesus promised his disciples, “It is for your good that I am going away. Unless I go away, the Counselor [Holy Spirit] will not come to you; but if I go, I will send him to you. … But when he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you into all truth. … All that belongs to the Father is mine. That is why I said the Spirit will take from what is mine and make it known to you” (John 16: 7, 13, 15). It certainly sounds like the Holy Spirit is a real, personal being. And that has been the verdict of Christian theology for 2,000 years.

Implications

As I mentioned in last week’s blog, “Losing the Gospel,” we cannot assume that Americans in general or even the people sitting in our pews (or watching on Zoom) understand the very basics of the Christian faith. As a lifelong Christian who has read the Bible and studied in seminary, these basics often seem like they are “old hat” to me. But for many people, the basics are “new news” that they are unfamiliar with.

The most pressing need is to address those who are uncertain about God. The fastest-growing group in the survey is those who say “a higher power may exist, but nobody really knows for certain.” That group “has exploded from 1 percent of the public thirty years ago to 20 percent today.”

We are on our way back to ancient Athens. Paul addressed the Athenians this way, “I see that in every way you are very religious. For as I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: TO AN UNKNOWN GOD. Now what you worship as something unknown, I am going to proclaim to you” (Acts 17:22-23). Paul then proceeded to teach them a biblical view of God. That is precisely what we need to do for the increasingly many who have no real idea who God is or what he is like. We have a great opportunity here for evangelism to people who are confused, but who are open to the idea of God.

An emphasis of our Wesleyan understanding of the faith is that we can have certainty about God. We call this the doctrine of assurance. We can be certain that God exists. We can be certain that he loves us and has sent his Son Jesus to die for us. We can be certain that we have been saved by his grace from sin and death to receive eternal life, if we have put our faith and trust in him.

Our faith is not a “hope so” kind of faith. We do not just hope that we have it right about God, we are certain, because he has revealed himself to us through his Son Jesus Christ, through the words of Scripture, and through the presence and power of the Holy Spirit. “Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see. … And without faith it is impossible to please God, because anyone who comes to him must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who earnestly seek him” (Hebrews 11:1, 6).

We do not need to buy into the uncertainty of our time. Instead, “we have this hope as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure. It enters the inner sanctuary behind the curtain, where Jesus, who went before us, has entered on our behalf” (Hebrews 6:19-20). As the old hymn puts it, “the anchor holds.” We have a firm and secure hope in a “God who is there, and who is not silent” (in the words of Francis Schaeffer). He has revealed himself to us and invites us to earnestly seek him.

In a time when the world seems to be falling apart, we can find security and hope in the God who made us, who loves us, and who gave himself for us. “Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; the one who seeks finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened” (Matthew 7:7-8).

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.

Those who worked at the plants and attended our church were executives and managers and engineers. Many of them had come from all over the country. He worked at one of the plants but he wasn’t like them. He was what we in Texas call “a good ol’ boy.” A laborer who drove a beat-up truck with a camper on the back, he didn’t wear the same clothes that my friends’ dads wore, wasn’t as cultured, wasn’t as successful, not in the way success is often measured.

I met him shortly after I had accepted Christ as a sixteen-year-old. A young man had been hired by our church for that summer and he led most of us to real faith in Jesus and our lives were changed. This was at the tail end of a revival that took place in the 1970s known as “The Jesus Movement.” It started with some hippies in California “getting saved” and then spread across the country. And in 1972 it reached my hometown and got me and my brother and the kids in my youth group.

But the summer ended, and the young man went back to school, and we were left with a bunch of parents and a pastor who loved us but who didn’t really understand what had happened to us. Some parents even wondered if maybe we were taking things too far. All we wanted to do was pray and worship and study the Bible. One father, the head of one of the plants and probably the wealthiest man in the church, bought us a new pool table and a new ping pong table, thinking that would get us back to being more of a traditional youth group – what we called MYF (Methodist Youth Fellowship) back then.

But he understood. The guy in the truck who didn’t go to our church. He knew what it was like to be completely captured by Jesus. He knew what it was like to be so enthusiastic that others misunderstood you and maybe even worried about you a little bit. And he knew that we needed someone who understood and who blessed what God was doing in our lives.

We lived fifty miles from Houston where there were some great churches where the Spirit of God was moving. And he wanted us to see it, to be a part of it, to know what was possible. So, we’d climb into his truck and he’d take us on a Friday night to a Christian coffee house or on a Sunday morning to a church with great praise music and powerful preaching. And we figured out that even if our parents didn’t quite get it or our pastor was a little concerned, what we had experienced of God and his Holy Spirit was real. It was how a relationship with Jesus was meant to be.

When we started the school year, we began to hold meetings on Tuesday evenings in our homes and invite other kids to come. We’d sing and pray, and one of us would get up and share the Gospel. We’d ask someone’s mom if we could come over and if she would bake some cookies. We would never tell her that some nights two hundred teenagers would show up. But they did and we’d have to meet outside, spread out over three front yards. At the end, we’d give an invitation and ten or twenty young people would give their lives to Jesus.

He was there. At every Tuesday night meeting we had. Not because he was a part of our church but because he loved us and he believed in us. He was there praying for us, watching us, watching over us. At the end he’d come up and say, “Boys, God really used you tonight.” “I could see God’s Spirit on you as you were preaching tonight.” “There’s a call on your life; you feel it, right?” “Oh, this is so good, what God is doing through you. No telling what he’s going to do with you in the future.”

The time he spent with us, the words he spoke to us, the encouragement he gave us, the vision he lifted up before us – the way he made us feel important and understood – the contribution he made to my life and the lives of others, I don’t know if I have ever been given a greater gift by anyone. I don’t know who I’d be or if I would have believed God was calling me into the ministry, if it hadn’t been for him.

We have such huge problems we’re facing. The pandemic. The economy. Race relations. Finding a way for the UM Church to separate and go in different directions. We need to work on those things. We must.

But I’ve come to believe it’s often the little things that make the biggest difference. A small act of kindness. A simple word of encouragement. Believing in someone and letting him or her know that we do. Throwing some kids in the back of your truck and taking them to where God is at work. And telling them when you see God using them.

You don’t have to be educated to do that. You don’t have to be wealthy to do that – or successful or cultured. You just have to have a heart for God and a heart for others. And someday, fifty year from now some guy may think back and wonder who he would have been without you. And with love in his heart and tears in his eyes will say, “Dear Jesus, thank you for him.”

![The Stumble of Grace]()

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

By Carolyn Moore –

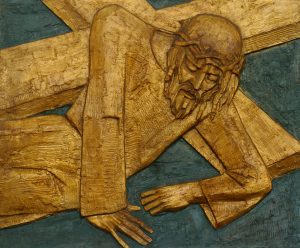

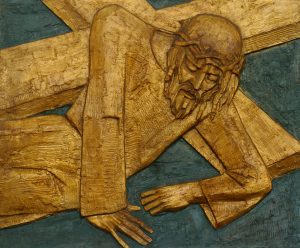

Ninth Station of the Cross. Photo by Zvonimir Atletic.

Like so many people, I’ve given chunks of time every day for months to pray against the virus, and against racism, and against all the crazy things that have cropped up as our collective nerves have gotten frayed. One of the best things I discovered during this season of prayer is the stations of the cross. I’d never had much use for them before. I think I just didn’t get them, but they’ve come alive for me in this season. I found out that you can pray the stations of the cross over just about anything and get clarity.

The stations of the cross are probably more familiar if you grew up Catholic or Orthodox. There are fourteen visual stations. The first one begins with Jesus being condemned to die and the last one is Jesus being laid in the tomb. The collection of them help us meditate from condemnation to death on the sacrifice of Jesus.

This is what I didn’t know about the stations of the cross before I first prayed them early on during our shut-down. I didn’t realize I could pray them over specific issues — that by meditating on the suffering of Jesus from condemnation to death as I prayed about the virus or about the sin of racism, I could see in a different light how Jesus suffered and died for those very things in order to overcome death and sin. I discovered the stations were a profound and rich way to bring the suffering of Jesus into our suffering. When we pray the stations contemplatively, we experience the truth that Jesus gets us. He loves us. He is in it with us.

The first time I prayed the stations with the virus in mind, I discovered a treasure embedded in this powerful, devotional visualization of Jesus’ journey toward his own crucifixion. At the third station, Jesus falls. He’d been condemned and handed a huge, heavy cross to carry, the same one he’d be nailed to. He was told to carry it to the place of his death, but eventually it became too much to carry. Too heavy. Jesus had already been beaten half to death and under that weight and in that weakened state, the Bible story tells us someone had to help him. It doesn’t specifically say he fell but it must have been obvious he needed help.

It is at the third station we think about Jesus falling for the first time under the weight of his cross.

But he gets up again and carries his cross a ways further down the road. Then at the seventh station we’re told to consider that Jesus might have fallen a second time. The fall itself isn’t in the scripture but the point of the station is to feel it, to feel the weight of this cross and all it holds and represents. This weight is more than just wood. It is us. It is everything we’ve done to make that cross a necessary burden to bear.

At the second fall, that weight seems unbearable. But Jesus keeps going. Somehow, he finds strength and purpose to get up again, to pick up this cross and keep carrying it with all that it holds. And now, if we are contemplating well, we are with him in this weight. We feel the pain. We taste the sweat and blood. We hear the people weeping and also the ones who are jeering, most of whom have no clue why.

Let’s be clear on this point. There is no Rocky Balboa moment among these stations of the cross, where Jesus catches his second wind. The scripture never says he one-hands the cross and trots up that hill. No. In fact, in the traditional stations of the cross there is a third stumble at the ninth station. It represents the struggle of this cross. It asks us to feel the full weight of the sin that piles on as we keep demanding our own way, the chronic impatience that is the default setting of humanity, the inability to see life from any other vantage point than our own.

That ninth station? It was the one that broke me the first time I prayed these stations with a group as we prayed against the virus. I know the Word well enough to know the backstory but still, I could feel the spirit behind this station. I became overwhelmed by the thought of stumbling people all around us — people who came into this crisis, into this year, already bearing the unbearable burdens of broken marriages and bad finances and addictions and illness. I could sense the pain of people who were already carrying more than they could bear, who had already stumbled more than once before they ever arrived at this pandemic.

That third stumble is also where we feel the cost of our own defects, of the things we so stubbornly hang onto because we can’t take one more change, or because we just don’t want to change. That is the weight he bore. And it wasn’t a game. It wasn’t easy. Yes, Jesus was all God, but he was also all human. He clearly felt the humanity of that walk up a hill with a cross on his back. Talk about courageous love! There is no power greater than the love of Jesus that compelled him to stand up from that stumble — not his, but yours — and to keep walking, to stay in it for the sake of all our stumbles. That ninth station asks us to see our part in this journey.

The tenth station of the cross represents the height of vulnerability as we contemplate them stripping Jesus of his garments so he would be left totally exposed. Do you think Jesus doesn’t feel your fear? Your horror at the thought of everyone finding out you’re a fraud? You think he doesn’t get what it feels like to be left hanging, literally hanging with no idea how all this is going to end, or when? My friend, Jesus gets you. He so gets you. That tenth station — Jesus brutalized, stripped, hanging — is the very image of truth and courage. Sheer strength.

Brene Brown’s definition of vulnerability is “having the courage to show up when you can’t control the outcome.” She says, “Vulnerability sounds like truth and feels like courage. Truth and courage aren’t always comfortable, but they’re never weakness.” When the Bible tells us that love always rejoices in the truth, we ought always to finish the sentence with, “… and truth takes courage.” Because it takes courage to stand, and then stand up again even when we stumble. It takes courage to be vulnerable and to admit when we are wrong and to stand up again and keep going. It takes courage to stay in the hard conversations, and to stay in community, and to stay in the fight but when we do, it is always in the spirit of Jesus. We surrender and we keep surrendering because Jesus keeps getting up again, keeps carrying that grace of a cross that bears what we can’t.

Jesus keeps finishing the work.

And we keep surrendering our heart because today, we may be carrying something we thought we could somehow bear on our own. And today, we may be adding to the weight of Christ’s sacrifice. Try as we might, at some point today we are going to demand our own way or get angry or impatient. At some point today, we’re going to stumble and what stands us up again is humility enough to surrender our weakness to the power of God. As Andrew Murray says, “Humility is the nothingness that makes room for God to prove his power.”

In recovery circles they say that daily surrenders are not how we keep from stumbling, but how we keep getting up again. We surrender as much of ourselves to as much of God as we understand and we keep surrendering, keep showing up even when we don’t get to control the outcome, because we trust the power of the cross to finish the work well.

Maybe the most courageous thing of all that we can do today is to fully own our selves — the good, the hard, the defects, the questions, the inadequacies and feelings of inadequacy, all of it. Maybe the most courageous thing we can do today is allow our hearts to be softened again by the love of a Messiah who knows what it feels like to stumble and who never gave up.

He never gave up on you then, and isn’t giving up on you now.

Carolyn Moore is the founding pastor of Mosaic United Methodist Church in Augusta, Georgia. She has written numerous books, including Supernatural: Experiencing the Power of God’s Kingdom (Seedbed). Dr. Moore serves as the Vice-Chair of the Council of the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.