by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.

Those who worked at the plants and attended our church were executives and managers and engineers. Many of them had come from all over the country. He worked at one of the plants but he wasn’t like them. He was what we in Texas call “a good ol’ boy.” A laborer who drove a beat-up truck with a camper on the back, he didn’t wear the same clothes that my friends’ dads wore, wasn’t as cultured, wasn’t as successful, not in the way success is often measured.

I met him shortly after I had accepted Christ as a sixteen-year-old. A young man had been hired by our church for that summer and he led most of us to real faith in Jesus and our lives were changed. This was at the tail end of a revival that took place in the 1970s known as “The Jesus Movement.” It started with some hippies in California “getting saved” and then spread across the country. And in 1972 it reached my hometown and got me and my brother and the kids in my youth group.

But the summer ended, and the young man went back to school, and we were left with a bunch of parents and a pastor who loved us but who didn’t really understand what had happened to us. Some parents even wondered if maybe we were taking things too far. All we wanted to do was pray and worship and study the Bible. One father, the head of one of the plants and probably the wealthiest man in the church, bought us a new pool table and a new ping pong table, thinking that would get us back to being more of a traditional youth group – what we called MYF (Methodist Youth Fellowship) back then.

But he understood. The guy in the truck who didn’t go to our church. He knew what it was like to be completely captured by Jesus. He knew what it was like to be so enthusiastic that others misunderstood you and maybe even worried about you a little bit. And he knew that we needed someone who understood and who blessed what God was doing in our lives.

We lived fifty miles from Houston where there were some great churches where the Spirit of God was moving. And he wanted us to see it, to be a part of it, to know what was possible. So, we’d climb into his truck and he’d take us on a Friday night to a Christian coffee house or on a Sunday morning to a church with great praise music and powerful preaching. And we figured out that even if our parents didn’t quite get it or our pastor was a little concerned, what we had experienced of God and his Holy Spirit was real. It was how a relationship with Jesus was meant to be.

When we started the school year, we began to hold meetings on Tuesday evenings in our homes and invite other kids to come. We’d sing and pray, and one of us would get up and share the Gospel. We’d ask someone’s mom if we could come over and if she would bake some cookies. We would never tell her that some nights two hundred teenagers would show up. But they did and we’d have to meet outside, spread out over three front yards. At the end, we’d give an invitation and ten or twenty young people would give their lives to Jesus.

He was there. At every Tuesday night meeting we had. Not because he was a part of our church but because he loved us and he believed in us. He was there praying for us, watching us, watching over us. At the end he’d come up and say, “Boys, God really used you tonight.” “I could see God’s Spirit on you as you were preaching tonight.” “There’s a call on your life; you feel it, right?” “Oh, this is so good, what God is doing through you. No telling what he’s going to do with you in the future.”

The time he spent with us, the words he spoke to us, the encouragement he gave us, the vision he lifted up before us – the way he made us feel important and understood – the contribution he made to my life and the lives of others, I don’t know if I have ever been given a greater gift by anyone. I don’t know who I’d be or if I would have believed God was calling me into the ministry, if it hadn’t been for him.

We have such huge problems we’re facing. The pandemic. The economy. Race relations. Finding a way for the UM Church to separate and go in different directions. We need to work on those things. We must.

But I’ve come to believe it’s often the little things that make the biggest difference. A small act of kindness. A simple word of encouragement. Believing in someone and letting him or her know that we do. Throwing some kids in the back of your truck and taking them to where God is at work. And telling them when you see God using them.

You don’t have to be educated to do that. You don’t have to be wealthy to do that – or successful or cultured. You just have to have a heart for God and a heart for others. And someday, fifty year from now some guy may think back and wonder who he would have been without you. And with love in his heart and tears in his eyes will say, “Dear Jesus, thank you for him.”

![The Stumble of Grace]()

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

By Carolyn Moore –

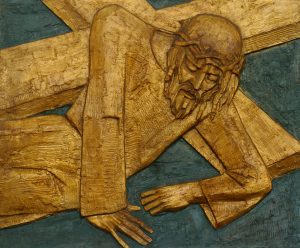

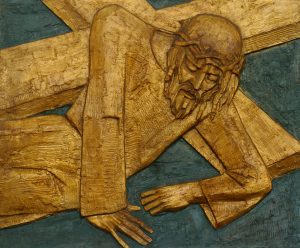

Ninth Station of the Cross. Photo by Zvonimir Atletic.

Like so many people, I’ve given chunks of time every day for months to pray against the virus, and against racism, and against all the crazy things that have cropped up as our collective nerves have gotten frayed. One of the best things I discovered during this season of prayer is the stations of the cross. I’d never had much use for them before. I think I just didn’t get them, but they’ve come alive for me in this season. I found out that you can pray the stations of the cross over just about anything and get clarity.

The stations of the cross are probably more familiar if you grew up Catholic or Orthodox. There are fourteen visual stations. The first one begins with Jesus being condemned to die and the last one is Jesus being laid in the tomb. The collection of them help us meditate from condemnation to death on the sacrifice of Jesus.

This is what I didn’t know about the stations of the cross before I first prayed them early on during our shut-down. I didn’t realize I could pray them over specific issues — that by meditating on the suffering of Jesus from condemnation to death as I prayed about the virus or about the sin of racism, I could see in a different light how Jesus suffered and died for those very things in order to overcome death and sin. I discovered the stations were a profound and rich way to bring the suffering of Jesus into our suffering. When we pray the stations contemplatively, we experience the truth that Jesus gets us. He loves us. He is in it with us.

The first time I prayed the stations with the virus in mind, I discovered a treasure embedded in this powerful, devotional visualization of Jesus’ journey toward his own crucifixion. At the third station, Jesus falls. He’d been condemned and handed a huge, heavy cross to carry, the same one he’d be nailed to. He was told to carry it to the place of his death, but eventually it became too much to carry. Too heavy. Jesus had already been beaten half to death and under that weight and in that weakened state, the Bible story tells us someone had to help him. It doesn’t specifically say he fell but it must have been obvious he needed help.

It is at the third station we think about Jesus falling for the first time under the weight of his cross.

But he gets up again and carries his cross a ways further down the road. Then at the seventh station we’re told to consider that Jesus might have fallen a second time. The fall itself isn’t in the scripture but the point of the station is to feel it, to feel the weight of this cross and all it holds and represents. This weight is more than just wood. It is us. It is everything we’ve done to make that cross a necessary burden to bear.

At the second fall, that weight seems unbearable. But Jesus keeps going. Somehow, he finds strength and purpose to get up again, to pick up this cross and keep carrying it with all that it holds. And now, if we are contemplating well, we are with him in this weight. We feel the pain. We taste the sweat and blood. We hear the people weeping and also the ones who are jeering, most of whom have no clue why.

Let’s be clear on this point. There is no Rocky Balboa moment among these stations of the cross, where Jesus catches his second wind. The scripture never says he one-hands the cross and trots up that hill. No. In fact, in the traditional stations of the cross there is a third stumble at the ninth station. It represents the struggle of this cross. It asks us to feel the full weight of the sin that piles on as we keep demanding our own way, the chronic impatience that is the default setting of humanity, the inability to see life from any other vantage point than our own.

That ninth station? It was the one that broke me the first time I prayed these stations with a group as we prayed against the virus. I know the Word well enough to know the backstory but still, I could feel the spirit behind this station. I became overwhelmed by the thought of stumbling people all around us — people who came into this crisis, into this year, already bearing the unbearable burdens of broken marriages and bad finances and addictions and illness. I could sense the pain of people who were already carrying more than they could bear, who had already stumbled more than once before they ever arrived at this pandemic.

That third stumble is also where we feel the cost of our own defects, of the things we so stubbornly hang onto because we can’t take one more change, or because we just don’t want to change. That is the weight he bore. And it wasn’t a game. It wasn’t easy. Yes, Jesus was all God, but he was also all human. He clearly felt the humanity of that walk up a hill with a cross on his back. Talk about courageous love! There is no power greater than the love of Jesus that compelled him to stand up from that stumble — not his, but yours — and to keep walking, to stay in it for the sake of all our stumbles. That ninth station asks us to see our part in this journey.

The tenth station of the cross represents the height of vulnerability as we contemplate them stripping Jesus of his garments so he would be left totally exposed. Do you think Jesus doesn’t feel your fear? Your horror at the thought of everyone finding out you’re a fraud? You think he doesn’t get what it feels like to be left hanging, literally hanging with no idea how all this is going to end, or when? My friend, Jesus gets you. He so gets you. That tenth station — Jesus brutalized, stripped, hanging — is the very image of truth and courage. Sheer strength.

Brene Brown’s definition of vulnerability is “having the courage to show up when you can’t control the outcome.” She says, “Vulnerability sounds like truth and feels like courage. Truth and courage aren’t always comfortable, but they’re never weakness.” When the Bible tells us that love always rejoices in the truth, we ought always to finish the sentence with, “… and truth takes courage.” Because it takes courage to stand, and then stand up again even when we stumble. It takes courage to be vulnerable and to admit when we are wrong and to stand up again and keep going. It takes courage to stay in the hard conversations, and to stay in community, and to stay in the fight but when we do, it is always in the spirit of Jesus. We surrender and we keep surrendering because Jesus keeps getting up again, keeps carrying that grace of a cross that bears what we can’t.

Jesus keeps finishing the work.

And we keep surrendering our heart because today, we may be carrying something we thought we could somehow bear on our own. And today, we may be adding to the weight of Christ’s sacrifice. Try as we might, at some point today we are going to demand our own way or get angry or impatient. At some point today, we’re going to stumble and what stands us up again is humility enough to surrender our weakness to the power of God. As Andrew Murray says, “Humility is the nothingness that makes room for God to prove his power.”

In recovery circles they say that daily surrenders are not how we keep from stumbling, but how we keep getting up again. We surrender as much of ourselves to as much of God as we understand and we keep surrendering, keep showing up even when we don’t get to control the outcome, because we trust the power of the cross to finish the work well.

Maybe the most courageous thing of all that we can do today is to fully own our selves — the good, the hard, the defects, the questions, the inadequacies and feelings of inadequacy, all of it. Maybe the most courageous thing we can do today is allow our hearts to be softened again by the love of a Messiah who knows what it feels like to stumble and who never gave up.

He never gave up on you then, and isn’t giving up on you now.

Carolyn Moore is the founding pastor of Mosaic United Methodist Church in Augusta, Georgia. She has written numerous books, including Supernatural: Experiencing the Power of God’s Kingdom (Seedbed). Dr. Moore serves as the Vice-Chair of the Council of the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

![The Stumble of Grace]()

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

Dr. William J. Abraham. Photo credit: Perkins School of Theology.

Dr. William J. Abraham is an irreplaceable Irish import to United Methodism. He is an ordained elder of the Rio Texas Conference and the Albert Cook Outler Professor of Wesley Studies at Perkins School of Theology in Dallas. He is the author of numerous books such as Divine Revelation and the Limits of Historical Criticism (Oxford), Crossing the Threshold of Divine Revelation (Eerdmans), Canon and Criterion in Christian Theology (Clarendon), The Logic of Evangelism (Eerdmans), and Wesley for Armchair Theologians (Westminster John Knox).

Several years ago, Abraham and Dr. David F. Watson teamed up to write Key United Methodist Beliefs (Abingdon). Watson, professor of New Testament and academic dean at United Theological Seminary, is a frequent contributor to Good News. We asked Dr. Watson to interview his colleague and mentor about a future transition into a new project. What follows is their exchange.

Dr. David F. Watson: You’ll soon retire from the Albert Cook Outler Chair in Wesley Studies at Perkins School of Theology, having taught at Perkins for 36 years. When you look back over your time at Perkins, what brings you the greatest sense of accomplishment? Do you wish you’d done anything differently?

Dr. William J. Abraham: Perkins has been a perfect setting for my work across the years. I have always seen myself as working in internal exile where I need the stimulus of radically different positions to drive me to think things all the way to the bottom. At Perkins I have had a front-seat in the articulation of two competing visions of theology: a neo-liberal position brilliantly worked out by Schubert Ogden and then a liberationist vision shared across much of the faculty. Albert Outler’s unrevised vision of Methodism was also in the picture; as was the work of more conservative scholars like Bruce Marshall, one of the sharpest Catholic minds in contemporary theology.

The resources for study and travel have been terrific. Bridwell library is magnificent. I am proud to have been honored with the top awards in both teaching and scholarship as well as the Lifetime Achievement Award in the university given two years ago.

So, I have been a happy warrior in the academy. It was a great decision to come and stay here for thirty-six years of labor as teacher and scholar. One of my greatest accomplishments has been the training of a cadre of scholars in the Graduate Program in Religious Studies who are now my teachers. I have no regrets.

It was recently announced that you’ve taken a position as Director of the Wesley House of Studies at Baylor University’s Truett Seminary. No doubt you’ve received many offers to work with and for other institutions over the years. What prompted you to accept Baylor’s offer, and what are your hopes for the House of Studies?

The decision to retire took six months to make and was formalized in December last year; it was far from easy. Several factors weighed with me. The clock is ticking, and I have several academic projects to finish. I want to spend more time in the former Soviet Union and in Romania where I have worked for the last ten years, helping establish a new church. I felt my time at Perkins was complete and it was time to move on.

Above all I wanted to reorient my work and ministry and felt that it was time to do something different. The Baylor offer came totally out of the blue after I had already formally signed my contract to retire.

It rekindled my love for working on Wesley and Methodism; I have a new edition of the canonical sermons that reads them as a handbook of spiritual direction in the works. More importantly, we need to find new spaces to pursue work in the Wesleyan tradition; Baylor as a top-flight university is a perfect setting. My dream is that the Wesley House at Truett becomes a first-rate, global center for Wesley Studies and for training for ministry.

How do you respond to people who might say that Methodist students should not be educated at a Baptist institution?

Baylor is a delight because it takes the Christian faith, broadly conceived, seriously as a university. This will be change from the more secular orientation that I currently occupy. Truett is a young school and full of energy with top-notch leadership in place. The Baptist heritage will provide friendly competition to provoke us to love and good works, including good intellectual work for the sake of the Wesleyan tradition. Sociologically, United Methodists tend to look up to the bigger battalions in church history while looking down on those beneath it; so, I know the game that is being played. Time will tell, but I bet in years to come the fruits in ministry will speak for themselves.

Dr. Abraham speaks at a gathering of the Wesleyan Covenent Association. Photo by Steve Beard.

It’s almost certain that a new, traditional Methodist denomination will form next year after the 2021 General Conference. What are your thoughts about how theological education should look for this new denomination? What should we do differently than we have in the past?

We face a cataclysmic future in theological education in United Methodism. Let’s be frank, even our best schools have not been hospitable to conservative students and faculty for years. This is going to get worse, so the challenge for the new church is enormous. We certainly have enough schools to be a platform on which to build. However, we will need to be creative as we move forward.

We need to have as much person-to-person teaching as possible; the crisis with Covid-19 makes this clear. If we could get a degree-granting institution to cooperate, we could look at the German Model where students can take intensive courses with the best of the best in various sites across the nation. Think of an itinerating tabernacle of scholars and students brought together to study and learn. In the worst-case scenario, we can always fall back on the online option; but we have to recognize the limitations of this option. We will find a way forward, but it will take time.

Over the years we’ve had many conversations about international theological education. In the United Methodist Church we’ve sometimes done well in this regard, and sometimes we haven’t. What challenges and opportunities do you see in the days ahead for the new denomination as it attempts to implement international programs for theological education?

This is way above my paygrade! My preference, as happens in my current work in Russia, is to do on-site teaching. Cliff College in England is the epicenter of innovation in this area and their work is very impressive. So, we will find a way forward. We need input from global Methodism; this requires supporting schools outside the United States so that they will have their own voice and integrity.

At present you’re finishing up a four-volume work on divine action. What do you mean by “divine action,” and why is it so important that you would devote four volumes to it?

Divine action is simply short hand for particular claims about what God has done, say, in history, or is doing now, say, in our lives and in particular providence. Once we look under the surface there are a host of issues to pursue. I have been working on them for fifty years and am now completing volume four. The first volume unpacks and resolves objections to divine action; the second is an immersion in the premodern tradition which identified various worries about specific divine actions; the third is devoted to systematic theology; and the fourth lays out an on-going agenda for the future.

I first got interested in the topic because of my dissatisfaction with Calvinism; I was smitten with issues related to human action in my undergraduate work in analytic philosophy and experimental psychology; and over time I was convinced that I could solve certain long-standing debates, such as the relation between grace and freedom.

That said, I have deliberately pursued serious detours into other terrain, notably, evangelism, the epistemology of theology, and Wesley Studies. I am currently pursuing long-standing interests in the relation between theology and politics. All these have provided invaluable insights on issues related to divine action. At heart I remain an Irish Methodist doing what I can for the fresh articulation of our heritage.

Your influence on at least two generations of orthodox, Wesleyan scholars has been considerable. For many of us, you’ve been a model, even a spiritual father. What advice do you have for those who have come after you in this work of preserving the faith once and for all entrusted to the saints?

I appreciate the kind words! On advice, let me try telegrams. Be anchored in a discipline that requires rigorous standards of excellence; for me that has been analytic philosophy. Stand by the truth and work on it until it becomes essential to your identity. Never, ever be up for sale, as far as the revelation of God mediated in Scripture is concerned. Stay grounded in regular ministry in the church. Take the politics of institutions seriously; be street-smart. Know your critics better than they know themselves. Always keep political commitments penultimate. Fast and pray as best you can!

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

By Kudzai Chingwe –

Rudo Sarah Mazamani, a United Methodist farmer in Headlands, Zimbabwe, washes her hands using a “tippy-tap” foot-pedal device, which is more hygienic than a traditional water tap. Photo by Kudzai Chingwe, UM News.

The founder of Methodism died on March 2, 1791, but his teachings remain relevant today amid a global pandemic. In his ministry, John Wesley established the concepts of class meetings for fellowship and the development of a disciplined spiritual life. During the weekly classes, small groups discussed how souls were prospering and provided opportunities for counsel and comfort. They also offered an avenue for collecting alms to aid the poor.

Wesley’s class concept has become especially relevant during and after lockdowns to stop the spread of the coronavirus as churches in Zimbabwe embrace small sessions to keep church attendance lower and encourage spiritual growth at home. The United Methodists in Zimbabwe join United Methodist seminary students in Russia who also have used Wesley’s small-group approach amid quarantine.

Zimbabwe President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangangwa gave the green light for the reopening of places of worship on June 11, but with strict rules on attendance and safety.

The Rev. Gift Kudakwashe Machinga, Zimbabwe East Conference board of discipleship chairperson and pastor-in-charge at Cranborne United Methodist Church in the Harare East District, said most United Methodist churches in Zimbabwe have turned to the use of class meetings, often called sections.

“Many churches within the Zimbabwe Episcopal Area have rekindled the Wesleyan class meeting type of worship services as the return to in-person worship came to play. The concept has varied advantages applicable now,” Machinga said. “In most circuits, including Cranborne, the use of sections is meant to maintain the required number of 50 (worshippers) and it is easy to adhere to the strict health prescribed preventative measures since the figure is small,” he added. He said the classes allow for easy contact tracing if a member tests positive for the coronavirus.

The Rev. James Matsungo, Chitungwiza-Marondera District connectional ministries director and pastor-in-charge of Hunyani United Methodist Church, said his circuit has 1,261 members divided into 32 sections. “During the reopening, we divided our congregants into seven services based on sections as a criterion,” Matsungo said. “Each service comprises four to five sections, depending on size,” he said, but the goal is to keep attendance at 50 or less. He said church leaders originally allocated 40 minutes for each service but have adjusted that to one hour to avoid overlap between groups and allow time to disinfect. “So far so good,” Matsungo said, “Hunyani church is alive and stable.”

Machinga said Wesley also was concerned about the health and wellness of a person. “John Wesley wrote a book titled ‘Primitive Physic,’ teaching people to use natural things to treat their ailments, including herbs,” he said, adding that he also established clinics in Britain – Bristol, Newcastle, and London – to distribute free medication to the poor.

“(He) was concerned about health issues and wanted people to worship God while healthy. He treated the soul and the body as one,” Machinga said. “If he was alive today, he would have encouraged people to take preventative measures during worship, give awareness, and be very careful with people not to contract the coronavirus as the churches return to a new normal.”

The Rev. Stanley Hwindingwi, pastor-in-charge at Mundenda United Methodist Church in the Mutasa Nyanga District, said rural areas have their own approach to reopening because they cannot afford many of the preventative protocols. “My church has adopted the section approach, but we are doing it in the open space to allow for ample space to maintain social distance, with plenty of fresh air circulation, and to avoid the need for sanitizing the sanctuary,” Hwindingwi said. He said he also travels to church members’ homes to hold services for small classes.

“We do not have adequate resources to buy the sanitizers and to meet the health requirements when using a sanctuary,” said Hwindingwi. “The use of sections helps us in the event that there is a suspected case — the risk is localized to the concerned section and easy to trace.” He said all congregants wash their hands with soap and water before and after the services.

“This method is sustainable for us. We also ensure that there are no handshakes allowed and we give awareness about Covid-19 every time before the service,” Hwindingwi said. “The (use of sections) has given me the opportunity to strengthen the church and have a close assessment of the state of the souls and assess any challenges which members are facing in their personal pursuit of holiness. Surprisingly, there is a positive increase in church remittances now,” he added.

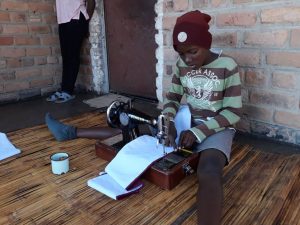

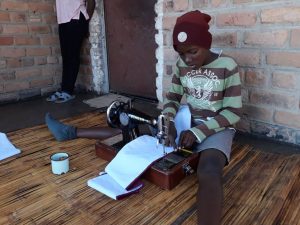

Fortune Muchatuki, a grade seven student at The United Methodist Church’s Hanwa Mission Center primary school in Macheke, Zimbabwe, sews a face mask. A recent $3,000 donation from the Baltimore-Washington Conference’s Zimbabwe Volunteers in Mission team provided material for face masks, food and other necessities. Photo by Kudzai Chingwe, UM News.

Chenayi Rushwaya, Chisipiti United Methodist Church health committee vice-chairperson, said that like Wesley, the church’s main concern upon reopening was the wellness of parishioners. “It took us four weeks to reopen after the president has given the churches the green light. We wanted to make sure that everyone would be safe,” Rushwaya said.

The Rev. Munyaradzi Timire, Zimbabwe East Conference education secretary, said lessons also could be learned from Wesley’s mother, Susanna, during the pandemic. “She used to teach her children (10 of her 19 children who survived) school work, moral, and religion (instruction). She would reserve an hour per day for each child. Today, some parents have adopted that (amid the pandemic),” she said.

Timire said permission to start e-learning has not been approved by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education in Zimbabwe, but the church is lobbying for distance learning to keep children safe. “Some parents have turned (into) teachers to bridge the gap … during this Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, the same way Susanna Wesley used to do,” Timire said.

Norah Mutanga, a nurse and wife of the Rev. Nyasha Mutanga of Chisipiti United Methodist Church, said after work, she conducts some lessons for her children. “This helps them to keep focused on education. When they go to school, they will catch up with other children and will be in a better position to write their examinations,” she said.

Machinga said John Wesley’s approach to ministry led to spiritual and numerical growth that is especially important today. “He left a legacy, which we must guard jealously. It is our heritage to preserve. His upbringing set him on the path of a lifelong quest for personal spiritual holiness that has created a ripple effect that is felt throughout the world, even today.”

Kudzai Chingwe is a communicator for the Zimbabwe East Conference. Distributed by United Methodist Communications.

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

By Justus Hunter –

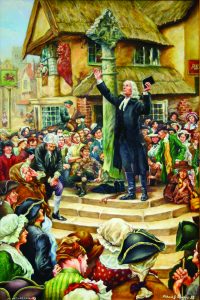

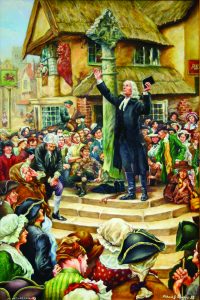

“Wesley Preaching at the Market Cross” by Richard Douglas, used with permission from Asbury Theological Seminary.

Demand for high quality and spiritually nourishing biblical commentary has been steady in the Wesleyan tradition. John Wesley’s Explanatory Notes on the Old and New Testaments were among his best-selling titles. Adam Clarke’s commentary on the Bible, despite Clarke’s controversial view of Christ, has been reprinted time and again over the past two centuries. And now, Kenneth Collins and Robert Wall have brought together an impressive team of Wesleyan scholars to produce the Wesley One Volume Commentary.

Not that there is any shortage of commentary on Scripture these days. Myriad commentaries populate the market. Some are one volume editions like this one, others are multivolume works. Some are written for academics, others for pastors. Most have hefty price tags, especially if they occupy multiple volumes. Thus, buying a commentary can feel a bit like choosing a mate. You better figure out what they’re really about before you commit.

What is the Wesley One Volume Commentary really about? Robert Wall puts it two ways: one precise yet dense, the other clear but slim. Here’s the former: “we seek … to produce a useful resource that will help initiate interested readers into a particular way of interpreting scripture’s metanarrative of God’s way of salvation for those who seek to live holy lives before a God who is light and love” (xxiii). And here’s the latter: “our intention is to encourage an approach to Bible study as God’s saving word for God’s people” (xxviii).

This pair of assertions carry several notable features. First and foremost, the aim of this text is initiatory – it hopes to guide its reader into a particular way of reading Scripture. Just as we enter the church through the waters of baptism, baptized Wesleyans, the editors hope, will find this text salutary for entering into a distinctly Wesleyan way of reading. And what is that way of reading? Whatever the methods and mechanics are, Wall insists that it has a single aim: salvation. The Bible is a saving word, and so its readers should find fitting study of this text leads them to work out their salvation, as James wrote and Wesley recited. As Wall puts it in the denser form, the Bible teaches the way of salvation, not as something to know, but that it might be put to use by those who seek to live holy, sanctified lives.

The Wesley One Volume Commentary is oriented toward this aim in tone, structure, and content. The intended audience stretches from educated laypeople to academics. It is organized according to the books of the Bible, and each individual book is clearly organized according to the fundamental structures of the biblical texts. Along with general biblical topics, the contributors emphasize the spiritual, theological, and especially Wesleyan themes of Scripture.

The volume opens with a pair of exceptional essays by the volume editors. Kenneth Collins, Professor of Historical Theology and Wesley Studies at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, gives an elegant and useful summary of Wesleyan doctrinal distinctives. The themes he recites recur throughout the volume, and prove adequate to the task of demarcating peculiarly Wesleyan interpretations of Scripture. He also nicely orients us to the relationship between “those doctrines of the Wesleyan faith that are shared with the broader Christian community,” and “emphases of the Wesleyan theological tradition, ongoing elements of its interpretive posture, that issue in a distinct vocabulary, conversation, and life” (xiv). This interplay, between that which constitutes what Thomas C. Oden called “consensual Christianity” and what William Burt Pope called Wesleyan “peculiarities” proves fruitful throughout the text.

Robert Wall, the Paul T. Walls Professor of Scripture and Wesleyan Studies at Seattle Pacific University and Seminary in Seattle, Washington, provides a probing and theologically sophisticated account of biblical interpretation from a Wesleyan perspective. His reading of Wesley’s own interpretive practice is concise and fecund, and his proposal for reading Scripture in the Wesleyan heritage is both faithful and generous. It is, quite honestly, one of the finest short essays on Wesleyan biblical interpretation I’ve encountered.

The book is well-structured in light of its aims. Each book of the Old and New Testaments receives a chapter, and each chapter supplies an overview, outline, and paragraph-by-paragraph summary of the text, followed by a brief bibliography. Readers will find the volume easy to navigate, the length suitable to enhance their understanding of the texts of Scriptures, yet, generally, without bogging them down in academic arcana. This is not to say the commentary is unlearned. The contributing authors are experts, but they are also, generally, effective communicators to inexpert audiences.

Contributors to the Wesley One Volume Commentary are well-selected. A nice variety of theological traditions are represented, all of which are Wesleyan or Wesleyan-adjacent. One finds numerous United Methodist, Free Methodist, Wesleyan Church, and Nazarene commentators. There are also contributors from both the Anglican Church of North America and The Episcopal Church. Pentecostal traditions, such as the Church of God (Cleveland), are represented. In short, the breadth of the Wesleyan heritage is included here, and so one finds several models, distinct in method yet unified in aim, for reading the Scripture as a Wesleyan.

Some of the contributions are simply spectacular. Brent Strawn’s commentary on Leviticus is, in itself, worth the expense of the entire volume. His commentary is informed and profoundly Wesleyan. For instance, Strawn rightly observes that Leviticus 19:18, “you shall love your neighbor as yourself,” was among John Wesley’s favorite verses (as, of course, it was for Christ). But Strawn also demonstrates, through a studied and elegant reading of Leviticus, the integral place of Leviticus 19:17 to the theology of Leviticus in general, and Leviticus 19:18 in particular. “You shall not hate in your heart anyone of your kin; you shall reprove your neighbour, or you will incur guilt yourself.” This union of reproof and love, Strawn shows, constitutes the heart of Leviticus’ holiness code, holiness in general, and the Wesleyan way of life. Wesley saw this, and argued as much in his sermon on Leviticus 19:17, “The Duty of Reproving our Neighbour.” And Wesley’s societies, especially in the confessional practices of the Wesleyan bands, enacted this principle. Thus the Wesleyan concept of holiness is grounded in Leviticus, and, as Strawn demonstrates, draws life from continued engagement with the text of Leviticus today.

Another exemplarily Wesleyan approach to the biblical text is found in Ruth Ann Reese’s commentary on the Book of Hebrews. Rather than isolating critical junctures for thick analysis of Wesleyan theology and practice, Reese takes Wesley along as a companion in her reading of the book of Hebrews. She helpfully shows, for instance, that Hebrews’ repeated appeals to its readers to pay attention (ch. 2), remain faithful (ch. 3), grow mature (chs. 5-6), choose endurance (ch. 10), and listen to God (ch. 12) contribute to the Wesleyan doctrine of sanctification, holiness, and perfection.

Of course, not every commentary is of the same quality. While the judicious reader will find much value in each commentary, judicious reading is sometimes necessary. The problems do not stem from the fundamental principles of the text or its stated aims. They stem from those moments when individual interpreters fail to live up to them.

Consider, for instance, a moment in an otherwise valuable commentary on the book of Proverbs by James Howell. Reflecting on the mundane concerns of the book of Proverbs, Howell insists that, “Wisdom understands that nothing is merely secular; everything is sacred. God made and cares about everything” (340). Well, sort of. Indeed, Christians, Wesleyan or otherwise, hold to the doctrine of creation from nothing. But they also insist that some things have gone wrong, so wrong that Paul speaks of waging war with the principalities and powers of this world (themes ably detailed by Suzanne Nicholson in her commentary on Ephesians later in the Wesley One Volume Commentary). This means that no Christian, and so no Wesleyan, can flat-footedly assert that “everything is sacred.” Some things are not. So, while it is true that activities which Howell defends are potentially enlivened by grace (the washing of dishes and the writing of checks), they are also potentially disordered by sin. This is the underlying presupposition of the book of Proverbs itself; there are both wise and unwise habits and practices to teach and share.

This is a minor criticism, but it is not a lone incident. Other imprecisions need similar refinement. When, for instance, L. Daniel Hawk speaks of Wesleyan theology as “relational” and therefore “against the doctrine of predestination” (190), we should again demur. Wesley did not object to any doctrine of predestination. To do so is to cease to be a Christian, or at least a biblical one. When the church canonized Paul’s words in Romans 8:29, “those whom [God] foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son,” she committed herself to some doctrine of predestination. Wesleyans simply disagree with one particular view of predestination, and offer their own as an alternative.

Overall, the volume fulfills its aims “to encourage an approach to Bible study as God’s saving word for God’s people” (xxviii) for those on the Wesleyan way to salvation with marked success. In those occasional places where particular commentators are imprecise, it is a departure from these noble aims. Most importantly, the volume corrects itself as all good theologians do, by an emphasis upon sacred Scripture itself. The path to thinking properly about wisdom and the holy should be pursued by reading Proverbs and Ephesians. The path to thinking properly about God’s predestination of our conformity to the image of the Son, which can only ever be the work of the Triune God, should be pursued by reading 1 & 2 Samuel and Romans.

The time is ripe for the Wesley One Volume Commentary. As the United Methodist Church, the largest body of North American Wesleyans, reaps the whirlwind for founding itself upon doctrinal indifferentism, we must be committed to sustained and devout reflection upon peculiarly Wesleyan ways of thinking and acting. We must learn again how to read the Scriptures in a Wesleyan way. Insofar as this volume supports that larger aim, it should be well-received. Hopefully, however, this is only a beginning. As Billy Abraham continues to remind us, the work of reinvigorating the Wesleyan way will be joyful, but substantial. It’s good work, but it’s still work.

I highly encourage the faithful on the Wesleyan way to purchase and study the Wesley One Volume Commentary. It invites, and indeed rewards, careful reading, much like the Scriptures around which the volume orbits. I am grateful for the contributing commentators, and above all the editors, for so robust a demonstration of the continuing power and prospect of the Wesleyan way of reading the Scriptures. And I pray that their aims will be fulfilled – that we might find that our study of the Bible is a reliable means for our transformation into the image of the Son, Jesus Christ.

Justus Hunter is assistant professor of church history at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of If Adam Had Not Sinned: The Reason for the Incarnation from Anselm to Scotus. (The Catholic University of America Press).

by Steve | Sep 14, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Sept-Oct 2020

By Scott Kisker

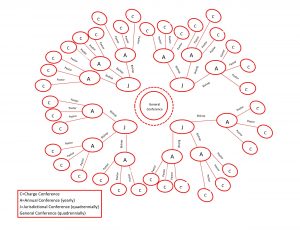

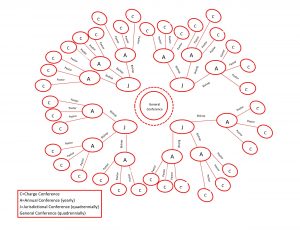

The Uniting Conference of 1939 called for a more “Methodistically informed” church. Photo: United Methodist Communications.

I officially joined the United Methodist Church in 1980 when I was confirmed. I was 12 years old. It was not a major event in my life, secular or spiritual. I had been through confirmation, but the only thing I remember was John Wesley being saved from a fire and thinking he was called by God. At the end of the course I had only one question. “If I say ‘yes,’ to this, does that mean that I have to be part of this church forever?” And by church I meant my congregation. I clearly didn’t get what confirmation was supposed to be about.

The answer I got back was, “No, you don’t even have to stay in the denomination.” While that was true enough, what I remember thinking in my adolescent brain was, “Well, I guess this doesn’t really matter.” So I got confirmed. No real faith. No real understanding of the Church. No concept of salvation. No conviction of sin. No encounter with the risen Lord of heaven and earth. But I was a member. I was a Methodist.

Discipline, Doctrine, Spirit. I tell that story to say that the problems of our United Methodist Church are not of recent making, nor are they related, except tangentially, to human sexuality. What we see today, a laxity in doctrine and discipline and a concurrent breakdown of the connection, didn’t happen overnight.

I remind you of that famous quote by John Wesley: “I am not afraid that the people called Methodists should ever cease to exist in either Europe or America. But I am afraid lest they should only exist as a dead sect, having the form of religion without the power. And this undoubtedly will be the case unless they hold fast to both the doctrine, spirit, and discipline with which they first set out” (“Thoughts Upon Methodism” in Wesley Works, 9:527, emphasis added).

The United Methodism I grew up in in the 1970s and 1980s had at best the “form of religion without the power.” It was no longer doctrinally clear, Spirit-led, or disciplined. We didn’t assume the goal for a Methodist was a radical encounter with the new creation and its Lord. We didn’t speak of a mission to “spread scriptural holiness across the lands.” No one ever accused us of Holy Spirit “enthusiasm.”

And this was not new to the late 20th century. I don’t think my mid-century parents knew any different form of Methodism. Methodists had been fudging what it meant to be Methodist, for the sake of popularity and cultural accommodation, for well over 80 years when I confirmed my baptism.

Historic Methodist Polity. I was asked recently whether United Methodism was a hierarchical or congregational polity. My answer, “Neither. We are connectional.” And while Methodists parrot platitudes about connectionalism all the time, most of us have no idea what actually constitutes the connection.

The Methodist connection was a series of connected accountable gatherings. This governance structure through gatherings is called conciliarism historically, or church government by council. We Methodists call these councils “conferences,” where we confer with each other to discern the leading of God.

Historically, the primary gathering, the base unit of “church” in Methodism, was the class meeting. These house groups of no more than 12 gathered weekly under the oversight of a lay class leader to watch over one another in love. Your membership was held in your class.

Those in good standing in a class gathered quarterly in a charge conference, what today we might call a church conference. These gatherings called and approved lay leadership and were overseen by an Elder – someone ordained, set apart, and sent for the oversight of word, sacrament, and order.

Representatives from charge conferences gathered yearly in annual conferences. Annual Conferences chose, ordained, and sent the elders to oversee charge conferences, and were likewise overseen by another Elder, a general overseer, whom we called a general superintendent or bishop.

The most authoritative and inclusive of these gatherings (including representatives from all other gatherings) was the General Conference. This catholic (or universal) gathering chose and sent the bishops to oversee the annual conferences. At General Conference, Methodists believed, God’s Spirit oversaw the general church as we conferred with one another, to ensure that catholic doctrine (universal across time and geography) and catholic discipline (universal across geography) were maintained for the sake of unity and witness in the world.

Class meetings gathered weekly to deal with personal matters. Class members gathered quarterly in a charge conference to deal with local matters. Charge conferences sent delegates yearly to annual conferences to deal with regional matters. Annual conferences sent delegates quadrennially to the General Conference to deal with general matters.

No conference could act in a way that violated the policies of the more inclusive conference of which it was a part, and to whom it was accountable. This was ensured by each gathering being watched over in love by someone chosen and sent from the more inclusive conference to which it belonged.

General Conference sent apostolic (or itinerant) bishops as officers of accountability to oversee annual conferences. Annual conferences sent apostolic (or itinerant) pastors as officers of accountability to oversee charges. Charge conferences approved class leaders.

General Conference sent apostolic (or itinerant) bishops as officers of accountability to oversee annual conferences. Annual conferences sent apostolic (or itinerant) pastors as officers of accountability to oversee charges. Charge conferences approved class leaders. Overseers were sent by and accountable to the conference who chose and sent them, class leaders to their charge conference, pastors to their annual conference, bishops to the general conference. Graphics: Firebrand.

Overseers were sent by and accountable to the conference who chose and sent them, class leaders to their charge conference, pastors to their annual conference, bishops to the general conference. This Apostolic oversight was at the heart of Methodist polity. “Watching over one another in love” and the “ministry of oversight” appeared at every gathering of Methodist people. This was “the connection.”

The Breakdown of Methodist Connection. This basic structure of Methodist gatherings with oversight remained in place until the early twentieth century, even as it came under increasing pressure from some Methodists who wanted a structure more like those of other more established churches or more congenial to early twentieth-century American culture.

The 1939 merger that formed The Methodist Church from the Methodist Episcopal Church, The Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and the Methodist Protestant Church, however, made the sweeping changes that altered this structure. These changes were done under the banners of unity, contextuality, and cultural influence. Sound familiar?

The requirement for class membership was removed from the discipline, eliminating the primary sphere for individual discipleship. Membership was now to the church or charge (though that language was falling out of favor).

The Judicial Council was introduced. Suddenly bishops seemed like an executive branch and the General Conference a legislative branch, giving us three branches of governance, in line with the assumptions of American secular government. We were THE American Church, after all.

Finally, we established a new gathering, a new conference, between General and annual conferences. This was the jurisdictional conference. These jurisdictional conferences were instituted ostensibly for the sake of unity, and greater ability to contextualize the gospel.

The southern church had put out all black members after the Civil War and did not want them back in their annual conferences. Nor did they want a northern bishop (unfamiliar with or unsympathetic to their context) sent to hold them accountable. Thus, to form a large, more contextual Methodist Church, black Methodists were segregated into a separate Central Jurisdiction. The whole church was then divided into jurisdictions.

Most significantly, there was no officer of accountability tying the new jurisdictional conferences to the General Conference and the general church’s decisions on doctrine and discipline. Bishops would no longer be chosen and sent forth from General conference to hold annual conferences accountable. Rather, they would be sent from contextualized jurisdictional conferences.

Methodist bishops were no longer “general superintendents” whose job was to watch over annual conferences for the General Conference. Methodist bishops were no longer catholic, in the sense of serving the whole church. Jurisdictional conferences were islands unto themselves, protected from interference from the General Conference, and so were bishops. They policed themselves within the isolated jurisdictions that elected them.

To accommodate American segregationism, Methodists severed the connection. What could go wrong?

30 Years Later. Skip forward to 1968 and 1972. With the merger of the Evangelical United Brethren and The Methodist Church, United Methodists decided not only to compromise discipline (as we had in 1939), but doctrine as well. Both churches’ doctrinal statements were included in the discipline in 1968. This was well and good. Both were sound. However, in the 1972 Discipline, both the Articles of Religion and Confession of Faith came to be referred to as “Landmark Documents,” whatever that meant. The statement titled “Doctrinal Guidelines in The United Methodist Church,” under “Our Theological Task” clarified this status (or lack of status):

“Since ‘our present existing and established standards of doctrine’ cited in the first two Restrictive Rules of the Constitution of The United Methodist Church are not to be construed literally and juridically, then by what methods can our doctrinal reflection and construction be most fruitful and fulfilling? The answer comes in terms of our free inquiry within the boundaries defined by four main sources and guidelines for Christian theology: Scripture, tradition, experience, reason. These four are interdependent; none can be defined unambiguously. They allow for, indeed, they positively encourage, variety in United Methodist theologizing. Jointly, they have provided a broad and stable context for reflection and formulation. Interpreted with appropriate flexibility and self-discipline, they may instruct us as we carry forward our never-ending tasks of theologizing in The United Methodist Church” (¶70, p. 75, emphasis added).

Doctrinal standards were “not to be construed literally and juridically.” The words needed not mean what they said, nor could anyone be held accountable to them. Although the doctrinal standards were still technically protected by the first Restrictive Rule, they were rendered impotent. Thus, the new UM Church subverted the purpose of the first Restrictive Rule, while technically leaving it intact.

Methodists were to engage in “free inquiry within the boundaries defined by … Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience.” Yet those “boundaries” could not be “defined unambiguously” and were to be interpreted with appropriate “flexibility.” As my colleague Dr. David F. Watson has written, with those caveats, why use the word “boundaries” at all?

Four years from the birth of our denomination, along with the invention of the “Quadrilateral,” United Methodism adopted a vague unstable doctrinal position that drained the Articles of Religion and the Confession of Faith of any real meaning or authority.

Attempts at Reform. Attempts were made to address this at General Conference. In 1988, the section on “Our Theological Task” was changed, to read, “Wesley believed that the living core of the Christian faith was revealed in Scripture, illumined by tradition, vivified in personal experience, and confirmed by reason.” It went on to state, “Scripture is primary, revealing the Word of God ‘so far as it is necessary for our salvation’” (¶ 69, p. 80).

But none of it mattered. The genie of undisciplined, unaccountable, “flexible” “theologizing” was out of the bottle. And thanks to the 1939 accommodation to segregation, there was no mechanism of accountability connecting bishops, annual conferences, or charge conferences to anything General Conference said or did.

Overseers no longer worked for the only body charged with discerning the Spirit for the whole Church. Bishops were only really accountable to the jurisdictions who chose and sent them. And jurisdictions were free to drift into sectarianism.

Episcopal oversight could be exercised according to a bishop’s conscience or the idiosyncrasies of his or her jurisdiction, with no fear of being called to heel by General Conference. And here we are.

Current Conditions. The week before the 2018 celebration of Trinity Sunday, a pastor who graduated from one of United Methodism’s more orthodox seminaries, posted a blog on the website UM Insight. In it he denied the nature of God, as preserved by the restrictive rule in our Discipline:

“We’ve made up elaborate theologies to help us describe how we think God relates to God’s self. The truth is this: our most complex Trinitarian theology and ideas are guesses. … The means in which we’re describing God’s relationships are not real. … Current Trinitarian explanations are just another box, limiting how [we] encounter God. Is it impossible for us to be honest: We really have no idea how any of this works.”

While he may be correct that none of us knows how the inner life of the Trinity “works,” that cannot excuse repudiation of ordination vows to uphold the doctrine and discipline of The United Methodist Church.

And just to clarify, Christians did not “make up” the Trinity. God spoke to his people through the incarnation of his Word and outpouring of his Holy Spirit – both divine, both worshipped, both in relationship with the Father, and both not the Father. Believers experience separate relationships with all three, and yet with one God. To deny the Trinity is to deny the full divinity of Jesus, the logos of God, the incarnation, or all of the above. This UM pastor seems not only to have given up on tradition, and Scripture, and experience, but reason as well. As far I know no overseer has disciplined him for misleading the sheep.

More shocking (not because it directly violated the Discipline, but because I had never imagined one would need such a proscription) was an ad sent to me about a church fundraiser. I know the church. It is in a community that started out as a Methodist camp meeting ground. The ad read:

“Last call for tickets!! This Saturday, June 4, 7 pm, in the historic Tabernacle … Spiritual Medium Gina Marie DeLuca. (You know, ‘I see dead people’ stuff). $40. Majority of proceeds going toward the United Methodist Church’s … capital campaign (building refurbishment & improvements).”

The pastor concluded with these words: “Yes, this is a church-sponsored event. And for those of you who believe mediumship is not compatible with Christianity, please remember Jesus spoke to the dead during his transfiguration (see Matt 17; Mark 9, Luke 9). Besides, if a loved one of yours had a message for you, wouldn’t you want to hear it? Feel free to share and hope to see you there!”

This pastor was raised in the United Methodist Church, attended a United Methodist undergraduate college, and got her MDiv from one of the official thirteen United Methodist seminaries. So far as I know, again, no oversight was exercised.

Serious issues. The issues around sexuality are serious. They are serious because no reasonable reading of the prophetic material in canonical Scripture can successfully tease out God’s demands for sexuality from God’s demands for economic justice, treatment of the alien, or idolatry. They are of a piece. But even bracketing sex for the moment, order has become chaos. And the question that hangs is whether, without order (as without word or sacrament) there is even a church.

When I was fifteen, a confirmed United Methodist wrestling with whether God was even real, I came to a sense of conviction about my desires and actions. Through the testimony of a youth leader and a couple of older boys I respected, Christians who witnessed to plain truth, I recognized an inflexible standard outside myself, a rule, against which I knew my flesh rebelled. Then, at sixteen, four years after I was confirmed, I came to real saving faith.

One positive thing about realizing just how messed up our accommodated unaccountable 20th century structure has been, is that people rarely repent until they find ourselves, like the prodigal son, at the end of their attempts to achieve what they think they want. The 2019 General Conference certainly made pig slop look tasty.

If we as a people called Methodist can indeed “come to ourselves” as the prodigal did, we might attempt a return home. If we repent, through the discipline with which we “first set out,” including genuine accountable oversight at each gathering for discernment, we might recover the doctrine and spirit (which was the anointing of the Holy Spirit) with which we “first set out.” We might become a church again.

Scott Kisker is Professor of the History of Christianity at United Theological Seminary. This article first appeared at Firebrand, a new online magazine (www.firebrandmag.com) and is reprinted here by permission.

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.

He didn’t go to our church. The truth is, he probably wouldn’t have fit in very well. I went to “First Church” where most of the members were professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, successful business owners. And many in my hometown worked at the oil and gas plants that it was known for – that and the distinct, distasteful smell they generated.