By Justus Hunter –

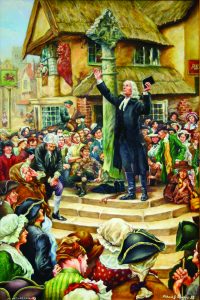

“Wesley Preaching at the Market Cross” by Richard Douglas, used with permission from Asbury Theological Seminary.

Demand for high quality and spiritually nourishing biblical commentary has been steady in the Wesleyan tradition. John Wesley’s Explanatory Notes on the Old and New Testaments were among his best-selling titles. Adam Clarke’s commentary on the Bible, despite Clarke’s controversial view of Christ, has been reprinted time and again over the past two centuries. And now, Kenneth Collins and Robert Wall have brought together an impressive team of Wesleyan scholars to produce the Wesley One Volume Commentary.

Not that there is any shortage of commentary on Scripture these days. Myriad commentaries populate the market. Some are one volume editions like this one, others are multivolume works. Some are written for academics, others for pastors. Most have hefty price tags, especially if they occupy multiple volumes. Thus, buying a commentary can feel a bit like choosing a mate. You better figure out what they’re really about before you commit.

What is the Wesley One Volume Commentary really about? Robert Wall puts it two ways: one precise yet dense, the other clear but slim. Here’s the former: “we seek … to produce a useful resource that will help initiate interested readers into a particular way of interpreting scripture’s metanarrative of God’s way of salvation for those who seek to live holy lives before a God who is light and love” (xxiii). And here’s the latter: “our intention is to encourage an approach to Bible study as God’s saving word for God’s people” (xxviii).

This pair of assertions carry several notable features. First and foremost, the aim of this text is initiatory – it hopes to guide its reader into a particular way of reading Scripture. Just as we enter the church through the waters of baptism, baptized Wesleyans, the editors hope, will find this text salutary for entering into a distinctly Wesleyan way of reading. And what is that way of reading? Whatever the methods and mechanics are, Wall insists that it has a single aim: salvation. The Bible is a saving word, and so its readers should find fitting study of this text leads them to work out their salvation, as James wrote and Wesley recited. As Wall puts it in the denser form, the Bible teaches the way of salvation, not as something to know, but that it might be put to use by those who seek to live holy, sanctified lives.

The Wesley One Volume Commentary is oriented toward this aim in tone, structure, and content. The intended audience stretches from educated laypeople to academics. It is organized according to the books of the Bible, and each individual book is clearly organized according to the fundamental structures of the biblical texts. Along with general biblical topics, the contributors emphasize the spiritual, theological, and especially Wesleyan themes of Scripture.

The volume opens with a pair of exceptional essays by the volume editors. Kenneth Collins, Professor of Historical Theology and Wesley Studies at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, gives an elegant and useful summary of Wesleyan doctrinal distinctives. The themes he recites recur throughout the volume, and prove adequate to the task of demarcating peculiarly Wesleyan interpretations of Scripture. He also nicely orients us to the relationship between “those doctrines of the Wesleyan faith that are shared with the broader Christian community,” and “emphases of the Wesleyan theological tradition, ongoing elements of its interpretive posture, that issue in a distinct vocabulary, conversation, and life” (xiv). This interplay, between that which constitutes what Thomas C. Oden called “consensual Christianity” and what William Burt Pope called Wesleyan “peculiarities” proves fruitful throughout the text.

Robert Wall, the Paul T. Walls Professor of Scripture and Wesleyan Studies at Seattle Pacific University and Seminary in Seattle, Washington, provides a probing and theologically sophisticated account of biblical interpretation from a Wesleyan perspective. His reading of Wesley’s own interpretive practice is concise and fecund, and his proposal for reading Scripture in the Wesleyan heritage is both faithful and generous. It is, quite honestly, one of the finest short essays on Wesleyan biblical interpretation I’ve encountered.

The book is well-structured in light of its aims. Each book of the Old and New Testaments receives a chapter, and each chapter supplies an overview, outline, and paragraph-by-paragraph summary of the text, followed by a brief bibliography. Readers will find the volume easy to navigate, the length suitable to enhance their understanding of the texts of Scriptures, yet, generally, without bogging them down in academic arcana. This is not to say the commentary is unlearned. The contributing authors are experts, but they are also, generally, effective communicators to inexpert audiences.

Contributors to the Wesley One Volume Commentary are well-selected. A nice variety of theological traditions are represented, all of which are Wesleyan or Wesleyan-adjacent. One finds numerous United Methodist, Free Methodist, Wesleyan Church, and Nazarene commentators. There are also contributors from both the Anglican Church of North America and The Episcopal Church. Pentecostal traditions, such as the Church of God (Cleveland), are represented. In short, the breadth of the Wesleyan heritage is included here, and so one finds several models, distinct in method yet unified in aim, for reading the Scripture as a Wesleyan.

Some of the contributions are simply spectacular. Brent Strawn’s commentary on Leviticus is, in itself, worth the expense of the entire volume. His commentary is informed and profoundly Wesleyan. For instance, Strawn rightly observes that Leviticus 19:18, “you shall love your neighbor as yourself,” was among John Wesley’s favorite verses (as, of course, it was for Christ). But Strawn also demonstrates, through a studied and elegant reading of Leviticus, the integral place of Leviticus 19:17 to the theology of Leviticus in general, and Leviticus 19:18 in particular. “You shall not hate in your heart anyone of your kin; you shall reprove your neighbour, or you will incur guilt yourself.” This union of reproof and love, Strawn shows, constitutes the heart of Leviticus’ holiness code, holiness in general, and the Wesleyan way of life. Wesley saw this, and argued as much in his sermon on Leviticus 19:17, “The Duty of Reproving our Neighbour.” And Wesley’s societies, especially in the confessional practices of the Wesleyan bands, enacted this principle. Thus the Wesleyan concept of holiness is grounded in Leviticus, and, as Strawn demonstrates, draws life from continued engagement with the text of Leviticus today.

Another exemplarily Wesleyan approach to the biblical text is found in Ruth Ann Reese’s commentary on the Book of Hebrews. Rather than isolating critical junctures for thick analysis of Wesleyan theology and practice, Reese takes Wesley along as a companion in her reading of the book of Hebrews. She helpfully shows, for instance, that Hebrews’ repeated appeals to its readers to pay attention (ch. 2), remain faithful (ch. 3), grow mature (chs. 5-6), choose endurance (ch. 10), and listen to God (ch. 12) contribute to the Wesleyan doctrine of sanctification, holiness, and perfection.

Of course, not every commentary is of the same quality. While the judicious reader will find much value in each commentary, judicious reading is sometimes necessary. The problems do not stem from the fundamental principles of the text or its stated aims. They stem from those moments when individual interpreters fail to live up to them.

Consider, for instance, a moment in an otherwise valuable commentary on the book of Proverbs by James Howell. Reflecting on the mundane concerns of the book of Proverbs, Howell insists that, “Wisdom understands that nothing is merely secular; everything is sacred. God made and cares about everything” (340). Well, sort of. Indeed, Christians, Wesleyan or otherwise, hold to the doctrine of creation from nothing. But they also insist that some things have gone wrong, so wrong that Paul speaks of waging war with the principalities and powers of this world (themes ably detailed by Suzanne Nicholson in her commentary on Ephesians later in the Wesley One Volume Commentary). This means that no Christian, and so no Wesleyan, can flat-footedly assert that “everything is sacred.” Some things are not. So, while it is true that activities which Howell defends are potentially enlivened by grace (the washing of dishes and the writing of checks), they are also potentially disordered by sin. This is the underlying presupposition of the book of Proverbs itself; there are both wise and unwise habits and practices to teach and share.

This is a minor criticism, but it is not a lone incident. Other imprecisions need similar refinement. When, for instance, L. Daniel Hawk speaks of Wesleyan theology as “relational” and therefore “against the doctrine of predestination” (190), we should again demur. Wesley did not object to any doctrine of predestination. To do so is to cease to be a Christian, or at least a biblical one. When the church canonized Paul’s words in Romans 8:29, “those whom [God] foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son,” she committed herself to some doctrine of predestination. Wesleyans simply disagree with one particular view of predestination, and offer their own as an alternative.

Overall, the volume fulfills its aims “to encourage an approach to Bible study as God’s saving word for God’s people” (xxviii) for those on the Wesleyan way to salvation with marked success. In those occasional places where particular commentators are imprecise, it is a departure from these noble aims. Most importantly, the volume corrects itself as all good theologians do, by an emphasis upon sacred Scripture itself. The path to thinking properly about wisdom and the holy should be pursued by reading Proverbs and Ephesians. The path to thinking properly about God’s predestination of our conformity to the image of the Son, which can only ever be the work of the Triune God, should be pursued by reading 1 & 2 Samuel and Romans.

The time is ripe for the Wesley One Volume Commentary. As the United Methodist Church, the largest body of North American Wesleyans, reaps the whirlwind for founding itself upon doctrinal indifferentism, we must be committed to sustained and devout reflection upon peculiarly Wesleyan ways of thinking and acting. We must learn again how to read the Scriptures in a Wesleyan way. Insofar as this volume supports that larger aim, it should be well-received. Hopefully, however, this is only a beginning. As Billy Abraham continues to remind us, the work of reinvigorating the Wesleyan way will be joyful, but substantial. It’s good work, but it’s still work.

I highly encourage the faithful on the Wesleyan way to purchase and study the Wesley One Volume Commentary. It invites, and indeed rewards, careful reading, much like the Scriptures around which the volume orbits. I am grateful for the contributing commentators, and above all the editors, for so robust a demonstration of the continuing power and prospect of the Wesleyan way of reading the Scriptures. And I pray that their aims will be fulfilled – that we might find that our study of the Bible is a reliable means for our transformation into the image of the Son, Jesus Christ.

Justus Hunter is assistant professor of church history at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of If Adam Had Not Sinned: The Reason for the Incarnation from Anselm to Scotus. (The Catholic University of America Press).

Thanks for this review and I look forward to having my own copy soon. But, I have a question: do any of us “reprove our neighbor?” Outside of the contentious General Conferences, I don’t see it happening. The only time I see reproof of neighbor is in editorial pages, or media commentaries. That’s not exactly what Leviticus 19:17 is talking about. I am thinking that there needs to be an established relationship of deep trust between me and my neighbor before such reproof will be effective. I pray I will be wise enough to establish such relationships with my neighbors – it takes time!