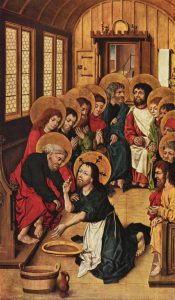

Christ Washing the Feet of the Apostles by Meister des Hausbuches, 1475

By Philip Yancy –

It began with a gathering at Denver’s snazzy Convention Center. I had agreed to host a forum with sixty business leaders before the Colorado Prayer Luncheon, but as a freelancer with precious little business experience, I had to search for something worth discussing. Fortunately, I had just read the new book by New York Times columnist David Brooks, The Second Mountain.

Brooks describes the journey on which successful people embark: enrolling in prestigious schools, climbing the corporate ladder, accumulating tokens of wealth and success. Then one day, some of these achievers wake up with a hollow feeling, wondering, “Is that all there is?” Others are gobsmacked by some event – the death of a loved one, a fractured marriage, bankruptcy – and find themselves in free fall. Now what?

I had listened to Brooks describe his own fall in an interview on Good Morning America. As a famous columnist and best-selling author, he reached an enviable summit. Yet when his 27-year marriage ended in divorce and depression set in, he realized he needed to climb another mountain, one that offered community and meaning. A friend told him, “I’ve never seen a program turn around lives. Only relationships turn around lives.” Hearing about a family who welcomed neighbors for a weekly dinner, Brooks showed up in his business suit one evening and rang the doorbell.

One of the neighbor kids opened the door, and Brooks stiffly extended his hand for a formal handshake. The kid looked him over, said, “We don’t do that here. We hug here,” and gave him a bear hug. Inside, Brooks found a household led by a warm, loving couple who hosted an average of 26 visitors from the neighborhood for dinner. For five years Brooks joined them on most Thursday evenings, and in time that diverse, lively community helped heal the loneliness in his soul.

To the business leaders, I read aloud Brooks’ conclusion: “The natural impulse in life is to move upward, to grow in wealth, power, success, standing. And yet all around the world you see people going downward. We don’t often use the word ‘humbling’ as a verb, but we should. All around the world there are people out there humbling for God. They are making themselves servants. They are on their knees, washing the feet of the needy, so to speak, putting themselves in situations where they are not the center; the invisible and the marginalized are at the center. They are offering forgiveness when it makes no sense, practicing a radical kindness that takes your breath away.”

David Brooks began exploring a second mountain, one in which ascent begins with apparent descent.

After the meeting with business leaders, we all moved to a huge ballroom. More than a thousand guests had assembled for the annual prayer luncheon, where Christian groups and individuals are encouraged to invite their nonreligious friends. As the speaker, I sat at the head table with the governor and mayor and several dignitaries from the city council. The elite of Denver, many of whom were busily checking their cell phones for last-minute messages, filled 140 tables around us.

The tone was somber for, just two days before, a suburban school had experienced a fatal shooting, a few weeks after the twentieth anniversary of the Columbine tragedy. The mayor, an African-American man who rose from homelessness to head a major city, practically preached a sermon, quoting Isaiah and urging us to care for the poor and the suffering. Meanwhile the governor, the first openly gay and the first Jewish person to hold that office, probably wondered who had scheduled him for an event among so many Christians. He responded with thoughtful remarks about the power of prayer in times of crisis. I tried to address both audiences: the Christian core, and their skeptical friends and colleagues who may have attended out of curiosity or civic obligation.

Three hours later I entered a federal prison. I had agreed to speak there as well, to honor ten men who had completed a rigorous four-year seminary program. The contrast in settings could not have been starker. Whereas the prayer luncheon was a fancy, dress-up affair, the prisoners all wore drab uniforms, with their names and numbers stenciled on the front. They lived behind bars and razor wire, ate institutional food each day, and were defined by their failures, not their successes. In David Brooks’ image, they had fallen off the first mountain, spectacularly.

I learned details of some of the graduates’ lives. One inmate started reading the Bible while in solitary confinement, and spent the next four years in the seminary course while also translating a German novel by Gerhart Haupmann called The Fool in Christ. Another had earned degrees in Biblical Studies and Theology and was working on a Masters in Divinity. Another said, “It was not until I came to prison that the Lord found me. I was the one that was lost and could not see. I was not only found but was able to see just how much the Lord loves me.”

One of the graduates wiped away tears as the recorded strains of “Pomp and Circumstances” filled the room. He later told me that his mother, who traveled from Nebraska to visit him every chance she got, had died that week. She would be buried back in Nebraska on Mother’s Day, and officials had denied his request to attend the funeral.

Although we were celebrating graduation from the seminary program, mostly the men spoke of another “graduation,” the day in 2021 or 2024 or whenever they would be released to resume life outside the prison walls. One inmate admitted addiction to some form of drug or alcohol from the age of nine. He had five drug-related felonies on his record, and was serving a 15-year sentence for distribution of meth resulting in a person’s death. He was using the time in prison to lose weight (75 pounds so far!) and hoped someday to work with kids in Teen Challenge, guiding them away from the path he had taken.

Another confessed that, after no more than seven years in school, he was barely literate and never read books. In prison he was working on his education and trying to “grow as a child of God.” He hoped in the future – “when I get out, God willing” – to return to prison as a teacher, training others. The seminary program, he said, “has helped me so much I must tell everyone about it.”

At the Colorado Prayer Luncheon we had enjoyed a full meal at tables set with cloth napkins and china. The prison served slices of carrot cake on paper plates with plastic forks. Though delicious, the cake had an unusual flavor of spices I couldn’t identify (“We have to improvise in this kitchen,” the chef admitted with a grin).

I left the prayer luncheon with a stack of business cards. I left the prison with empty pockets – we had to lock all belongings in our cars before entering – yet inspired by the stories of redemption I had heard. A late-spring snow was falling as the electric gate clanged shut and I walked out with a group of volunteers who have been coming for years, without pay or fanfare, to bring hope and renewal to the inmates locked inside.

The prisoners, volunteers and, yes, David Brooks have all learned the same lesson, that to climb the second mountain, ascent begins with apparent descent.

Philip Yancey is the author of innumerable books, including best-sellers such as Disappointment with God, Where is God When it Hurts?, The Jesus I Never Knew, What’s So Amazing About Grace? and Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference? This article first appeared on his website (philipyancey.com) and is reprinted here by permission.

Great article. Proves that there is grace at the end of the road for all who will receive it.