The Both/And Solution

By Thomas Lambrecht

A recent article by Jefferson Knight, a Liberia General Conference delegate, crystalizes the “critical decision” (in his words) facing United Methodists in Africa. He sees disaffiliation in Africa as a threat to “disintegrate the UMC in Africa and erase [it’s] rich history and heritage.” He sees regionalization as “a viable alternative … that promises to uphold the unity and continuity of the church while honoring its legacy.” The title of his editorial speaks of “Embracing Regionalization Over Disaffiliation.”

I will engage with some of his arguments in a moment, but first I want to call attention to his framing of disaffiliation and regionalization as stark alternatives that demand one to choose between them. What if General Conference delegates chose both?

There is no question that regionalization would mark a radical readjustment in the way the UM Church is governed. Many important decisions that used to be made at the global level would now be made at the regional level, potentially leading to significant differences in practices and governance between regions.

Regionalization is a legitimate path for the UM Church to take, although I personally disagree with it. It is a choice to go in a different direction from the way our denomination has functioned for over 230 years.

The question is: What accommodation will the UM Church be willing to make for those who disagree with taking this new direction? The church may be radically changing, but not everyone is on board with the trajectory of those proposed changes.

This is where disaffiliation comes in. It provides a way to accommodate those who strongly disagree with the new direction proposed by regionalization. For some who disagree, the new direction is not a big enough concern that they would want to depart from the denomination over it. For others, however, it represents a fundamental reworking of the church’s governance that they cannot in good conscience accept.

Much of the African UM Church has grown up over the past 20 years. New annual conferences have been added to the denomination. Existing annual conferences have seen tremendous growth in some areas. All of this growth has taken place under the current covenant of global governance.

Now, the terms of the membership covenant are proposed to change to regional governance. Would it not be fair to allow those who cannot embrace this change to exit from the denomination? They should not be forced to accept such a fundamental change just because they are in the minority.

It would be like a baseball league deciding that it wanted to change to adopt the rules of cricket. Some of the league’s teams might be willing to make such a change. But other teams might say, “We joined the league to play baseball, not cricket. If you are going to play cricket, we don’t want to play anymore.” Given the fundamental nature of that change, it would be fair to allow such teams to depart from the league and keep all their equipment, so they could continue to play baseball in a new league.

The same is true of United Methodism. Not only is there proposed a fundamental change from global to regional governance, it is also likely that the denomination will change its definition of marriage, allow pastors to perform same-sex weddings, and ordain partnered gays and lesbians as clergy. This level of change would in some ways transform the nature of the denomination. Those “teams” (annual conferences and local churches) that do not want to go along with such a fundamental transformation of the “rules” should have the opportunity to depart and keep their “equipment” (buildings and property), so they can continue to do church in the way they have done it in the past and according to their deeply-held beliefs.

Allowing annual conferences outside the U.S. and local churches to disaffiliate also helps the cause of regionalization. Those who remain would be those committed to implementing the new way of doing church. Those who oppose the new direction would not be around to resist its implementation.

Regionalization would require amendments to the constitution, for which it is necessary to have a two-thirds vote of approval both at the General Conference and in the cumulative voting of annual conferences. More than half the members of the UM denomination are located in Africa. If even a significant portion of participants in African annual conferences vote against regionalization, it would be defeated, even if it passed at the General Conference, since it would only take one-third of the total votes to block it.

Would it not be better for regionalization to allow those opposed to disaffiliate, rather than risk losing this new direction in order to hang on to the dissenters? Opponents of regionalization may or may not choose to disaffiliate. That is their choice to make – or it should be. But those opponents who choose to remain in the UM Church would be agreeing to go along with the new direction, even if they disagreed with it previously. The important point is that it would be their choice, not forced upon them due to the lack of an opportunity to disaffiliate.

If a disaffiliation pathway is provided at the General Conference, it is entirely possible that the regionalization proposal would pass the two-thirds vote, both there and in the annual conference vote. If there is a way for churches to disaffiliate, they would no longer feel bound to block regionalization, since they would not be forced to live under that new system.

Rather than choose one side or the other of a false dichotomy, General Conference delegates could choose a both/and solution, providing both disaffiliation and regionalization.

Arguments Against Disaffiliation

Knight makes a number of arguments against disaffiliation. These are valid points to consider by those discerning whether or not to disaffiliate. After all, there are pros and cons to disaffiliation, just as there are pros and cons to remaining United Methodist. The point is that Africans should have the opportunity to do that discernment and make their own choice, just as Americans did.

Knight believes that by disaffiliating, Africans would “risk isolating themselves from a broader network of support and resources … Moreover, disaffiliation could result in the loss of vital connections with sister churches worldwide, hindering opportunities for collaboration and mutual growth.”

Such isolation and loss of connection is certainly possible if those who disaffiliate remain independent or autonomous. However, if those who disaffiliate from the UM Church also affiliate with a new denomination, they can maintain some of their existing support and connections, while having an opportunity to build new ones. For example, the Global Methodist Church emphasizes missional partnerships that link grass-roots churches in the U.S. with churches in other areas for mutual ministry and support. These partnerships hold the potential for increased connection, not the loss of connection. Other denominations have similar missional approaches.

Knight further states, “the dissolution of the UMC in Africa through disaffiliation would represent a profound loss of heritage and history for the church.” Disaffiliation would probably not result in the “dissolution of the UMC in Africa.” Some would want to remain UM, and the UM Church would continue to have a presence at least in some parts of Africa. And the heritage and history of Methodism would remain, even if expressed through a different denomination. Parts of Africa were evangelized under the Methodist Church, prior to the 1968 founding of United Methodism. Their heritage and history continued in the new denomination. If those who disaffiliate remain Methodist in their beliefs, practices, and associations, the “wealth of knowledge and experience accumulated over centuries” would be maintained and strengthened, not “forgotten and diluted,” as Knight worries.

Depending upon how it is carried out, disaffiliation could “lead to fragmentation and discord within the church” as Knight contends, or it could be the beginning of a new chapter of growth in discipleship as a continuation of Methodism in a new vessel. African United Methodists tend to operate on a consensus model, meaning that they tend to act in unison, for the most part. There is hope that those who choose to disaffiliate would be able to do so as a united block, bringing the vast majority of their annual conference together in the direction chosen.

Arguments for Regionalization

Knight maintains that “regionalization offers a path forward that preserves the unity and continuity of The United Methodist Church in Africa and elsewhere while honoring its heritage and legacy.” He envisions the African church able to form “a cohesive network within the global denomination,” thus “maintain[ing] their connection to the broader church body while fostering a sense of solidarity and shared purpose.”

Without the opportunity for disaffiliation, regionalization alone will not “preserve the unity and continuity” of the church in Africa. Advocates for same-sex marriage and the affirmation of homosexuality continue to visit churches in Africa in order to promote their views. Division over these issues will come to Africa, just as it has come to America.

We have seen some more progressive churches in the U.S. draw back from their partnerships with churches in Africa and elsewhere because of differences over sexuality. As the U.S. church becomes more openly and officially affirming of same-sex relationships, the pressure will grow on African churches to change their views. That pressure might include conditions attached to missional support from U.S. churches that would force African churches into awkward choices between remaining faithful to their long-held traditionalist views or adapting their views in order to receive more support.

As we have made the case before, regionalization is more likely to lead to differentiation between regions and increased regional autonomy, rather than the unity and cohesion that Knight envisions. As regions feel empowered to adapt the Discipline to their liking, different regions are likely to function in different ways, have different standards, and even evolve different teachings on some issues. This is hardly a recipe for cohesion and unity.

The points Knight raises are valid points to consider, and they are ones where people of goodwill can disagree. The discussion is important to have in the context of whether to disaffiliate or to remain in a regionalized UM Church. African churches can and should make their own choices, and Americans should honor those choices. Adopting disaffiliation pathways at General Conference in addition to any regionalization proposals would enable there to be real choices for African churches. Out of respect for the dignity of our brothers and sisters in Christ, we can do no less.

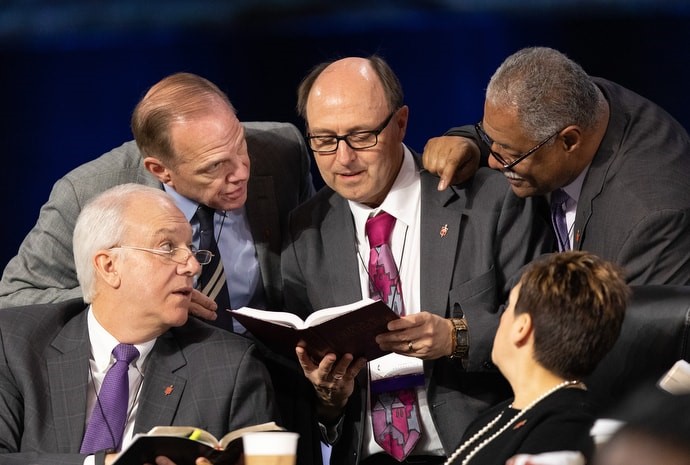

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News. Bishop David Bard (center) confers with fellow bishops on an issue during the 2019 United Methodist General Conference in St. Louis. File photo by Mike DuBose, UM News.

Those who want to change the rules in defiance of scripture should be the ones to leave.

However, perhaps the church should not be abandoned, but rather upheld steadfast, so those chasing error might be persuaded back to truth within the fold.