by Steve | Nov 10, 2022 | In the News

Methodist Heritage: Spirit May Join Many Protestants

By Louis Cassels, United Press International

April 6, 1967

Published in The Ledger & Times (Murray, Kentucky)

The ecumenical spirit has persuaded Protestants and Catholics to accent one another as brothers in Christ.

Perhaps it can now achieve a similar miracle within the Protestant family by overcoming the antagonism and mutual contempt which have so long characterized relations between liberals and fundamentalists.

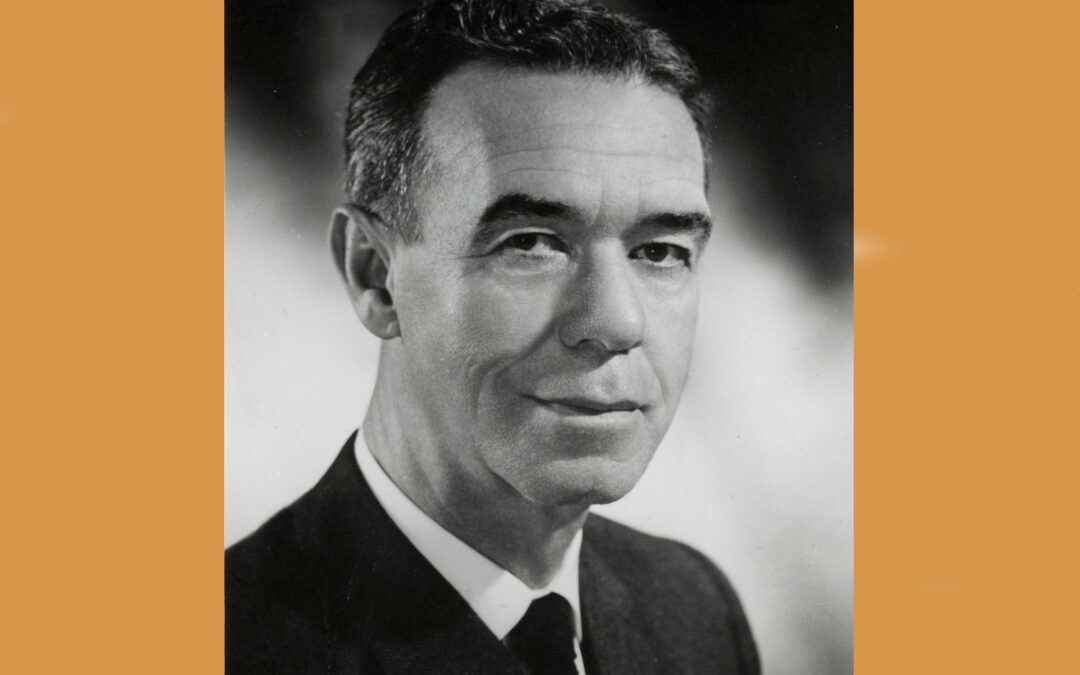

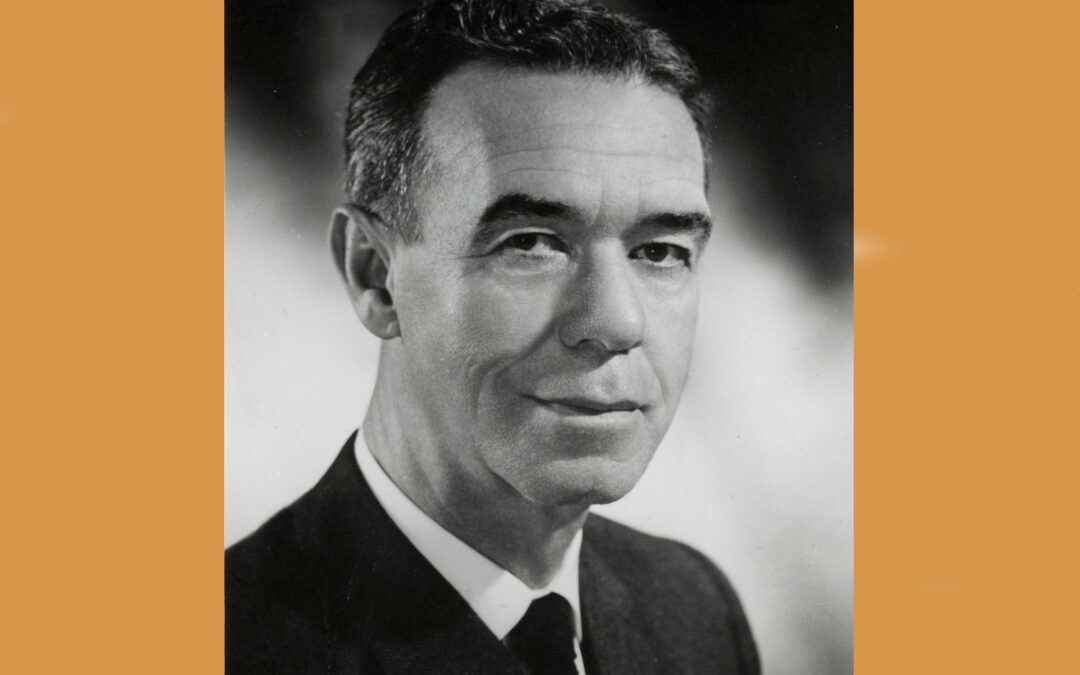

That hope was voiced this week by a prominent Protestant liberal Methodist bishop Gerald Kennedy of Los Angeles.

He contributed the lead article to a new magazine called “Good News” which was launched to provide a forum for evangelical or fundamentalist views in the Methodist Church.

“I am convinced that the main obstacle which faces us is not our differences, but the spirit in which we hold them,” said Bishop Kennedy.

“I have known some fundamentalists so narrow and bitter that it was impossible to talk to them … I have also known liberals who were so dogmatic and unbending that they could put the fundamentalists to shame.”

Bishop Kennedy acknowledged that “it is hard for a man with a great conviction to believe that a man who differs with him is honest.

“But this is one of the miracles which Christ works for us, and we ought to pray that he will touch us with his grace….

“We need each other Instead of merely putting up with somebody who is different than we are, let us thank God that he gives us an authentic witness from the other side of the hill.”

Is Grateful

As a liberal, he said, he is grateful to fundamentalists for their “emphasis is on the unchanging and eternal verities of our faith.”

He asked fundamentalists in turn to respect the Christian motivation of liberals who “feel so strongly about the relevancy of the church that they want to find ways to make it speak to the modern world.”

######

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | May/June 2018

Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Into the Arms of Eternity: Remembering Billy Graham

By Steve Beard –

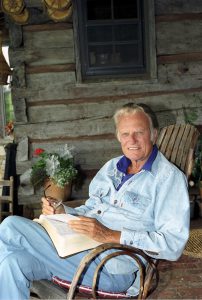

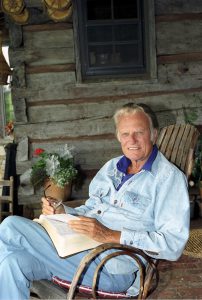

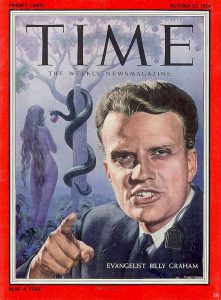

Wherever he landed around the globe, Billy Graham spent his life preaching a simple and sincere message of God’s love for all people, the urgent need for conversion, and the assurance that Jesus Christ walks with believers in the brightest and darkest of times. Throughout his illustrious ministry, Graham preached to nearly 215 million people in more than 185 countries and territories via his simulcasts and rallies. His audience exposure leaps exponentially when television, newspaper columns, videos, magazine stories, webcasts, and best-selling books are factored in.

Illustrative of his technological wizardry, Graham once spearheaded an event more than two decades ago that astonishingly utilized 30 satellites broadcasting taped evangelistic messages from Graham in 116 languages to 185 countries.

The news of his death on February 21 at his home in Montreat, North Carolina, at the age of 99, was observed with both joy and sorrow. The lanky world-renowned evangelist was buried in a rudimentary pine plywood coffin made by men convicted of murder from the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

For Christians, Graham was a role model in holding firm to both evangelism and integrated social action, orthodoxy and generous ecumenism, grace and truth, love and repentance. In addition to preaching his life-transforming message, he was pivotal in helping form numerous evangelical institutions that will be remembered as part of his fruitful legacy.

“Billy Graham was a man with beautiful integrity, clothed with humility, and combined with a sterling message of the gospel,” Dr. Robert Coleman, author of The Master Plan of Evangelism, told Good News. Coleman was a close friend and associate of Graham for 60 years, leading the Institute of Evangelism in the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College and serving as Dean of the Billy Graham International Schools of Evangelism. Coleman was one of a handful of United Methodists who attended Graham’s funeral along with Drs. Eddie Fox, Maxie Dunnam, and Timothy Tennent.

“Wherever we traveled around the world, Billy was a master of making a nobody feel like a somebody,” Coleman recalled. “You always felt lifted up in his presence. Whether you were a street sweeper or a king, Billy saw you as someone deeply loved and treasured by God.”

Although most well known as a Baptist, Graham had a special relationship with Methodists dating back to his early friendship with lay evangelist Harry Denman, a man Graham described as “one of the great mentors for evangelism in my own life and ministry – and for countless others in evangelism as well.” Denman, who died in 1976, was the leader of the Commission on Evangelism of the Methodist Church. In the forward to the book Prophetic Evangelist, Graham wrote: “I never knew a man who encouraged more people in the field of evangelism than Harry Denman.”

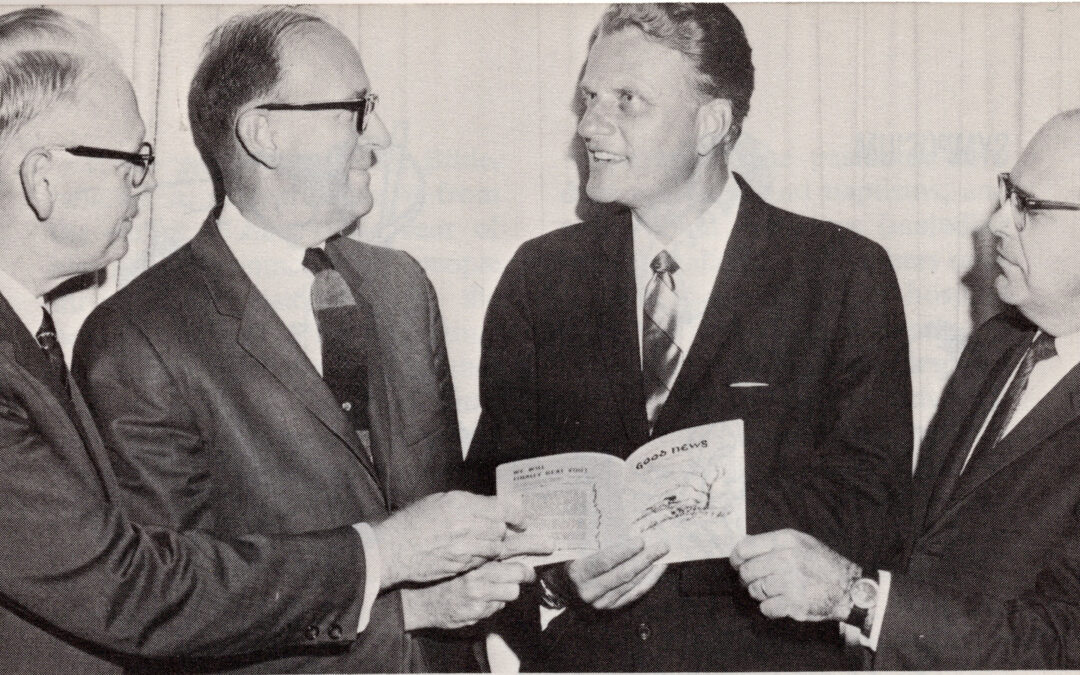

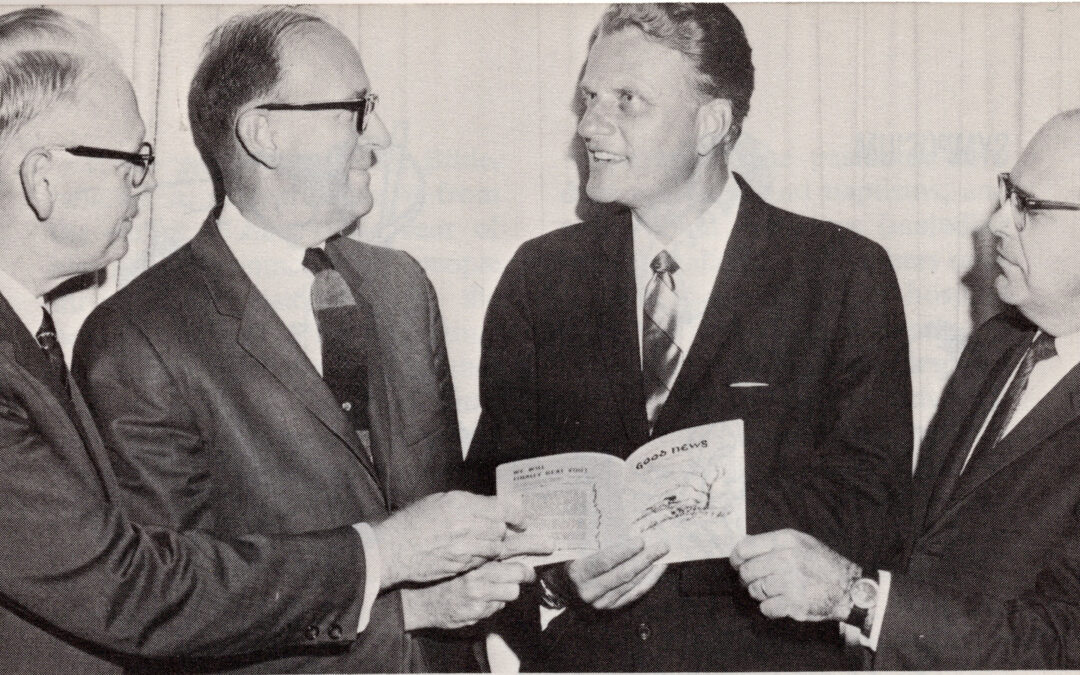

Methodist Bishop Gerald Kennedy’s position as chairman of the Billy Graham rally in Los Angeles in 1963 caused a controversial stir among fundamentalists and others who did not see a place for mainline denominations in Graham’s evangelistic efforts. In the premier issue of Good News in 1967, Kennedy wrote that he had hoped his position would be an opportunity to bring conservative evangelicals and mainline churches closer together. “We never succeeded at eliminating all our differences,” he wrote, “but we did make progress in talking to one another and trying to listen to each other with some appreciation.”

Over the decades, United Methodists were inspired by Graham’s message, temperament, and integrity. “No voice in the past half-century has been more powerful and faithful in pointing clearly to Jesus Christ than the message of Billy Graham,” Dr. Eddie Fox, former World Director of World Methodist Evangelism, said. “His message always led persons to Jesus Christ.” Fox was a speaker at several of the Billy Graham Schools of Evangelism.

According to United Methodist News Service, the late Bishop Leontine Kelly, who headed the evangelism unit of the denomination’s Board of Discipleship before her election to the episcopacy in 1984, characterized Graham’s preaching as “electric.” “His purposes were clear and his commitment to Jesus Christ was unwavering,” said Kelly, who died in 2012. “We will always be grateful for television, which enabled his communication of the gospel of Jesus Christ to millions.”

Graham had unparalleled reach. A 2005 Gallup poll revealed that 16 percent of Americans had heard Graham in person, 52 percent had heard him on radio, and 85 percent had seen him on television.

“Only the large expressive hands seem suited to a titan,” biographer William Martin, author of A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story, observed. “But crowning this spindly frame is that most distinctive of heads, with the profile for which God created granite, the perpetual glowing tan, the flowing hair, the towering forehead, the square jaw, the eagle’s brow and eyes, and the warm smile that has melted hearts, tamed opposition, and subdued skeptics on six continents.”

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

In hindsight, Graham registered his regret for not participating in civil rights demonstrations. “I think I made a mistake when I didn’t go to Selma, [Alabama in 1965],” Graham confessed to the Associated Press in 2005. “I would like to have done more.” It has been properly noted that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. considered Graham an ally. “Had it not been for the ministry of my good friend Dr. Billy Graham, my work in the Civil Rights Movement would not have been as successful as it has been,” said King. Other African American leaders, however, regret that Graham was not more front-and-center in the struggle.

“Graham clearly felt an obligation to speak against segregation, but he also believed his first duty was to appeal to as many people as possible. Sometimes he found these two convictions difficult to reconcile,” Martin wrote in A Prophet with Honor.

Close proximity to the corridors of political power – especially the Nixon White House – occasionally blindsided Graham. When asked in 2011 by Christianity Today, a magazine he helped launch, if there was anything he would have done differently, Graham responded: “I would have steered clear of politics. I’m grateful for the opportunities God gave me to minister to people in high places; people in power have spiritual and personal needs like everyone else, and often they have no one to talk to. But looking back I know I sometimes crossed the line, and I wouldn’t do that now.”

Of his regrets, those closest to home were the most sensitive. “Ruth says those of us who were off traveling missed the best part of our lives – enjoying the children as they grew. She is probably right. I was too busy preaching all over the world.” Ruth Bell married Graham in 1945 and the couple had five children. “I came through those years much the poorer psychologically and emotionally,” he reflected. “I missed so much by not being home to see the children grow and develop.”

Graham questioned some of the aspects of his jet-setting ministry. “Sometimes we flitted from one part of the country to another, even from one continent to another, in the course of only a few days,” he recalled. “Were all those engagements necessary? Was I as discerning as I might have been about which ones to take and which to turn down? I doubt it. Every day I was absent from my family is gone forever.”

Johnny Cash and Billy Graham. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Although Graham never had regrets about committing his life to preaching a Christian message, he wished he would have spent more time in nurturing his own personal spiritual life. “I would spend more time in prayer, not just for myself but for others,” he said. “I would spend more time studying the Bible and meditating on its truth, not only for sermon preparation but to apply its message to my life. It is far too easy for someone in my position to read the Bible only with an eye on a future sermon, overlooking the message God has for me through its pages.”

Boxing champion Muhammad Ali meets with Ruth and Billy Graham at their North Carolina home. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

“He brought down the storm.” Three years ago, Bob Dylan called Graham the “greatest preacher and evangelist of my time — that guy could save souls and did.” The music icon testified in AARP The Magazine to having attended some Graham rallies in the 1950s and ‘60s and described them in a distinctly Dylanesque way: “This guy was like rock ’n’ roll personified – volatile, explosive. He had the hair, the tone, the elocution – when he spoke, he brought the storm down. Clouds parted. Souls got saved … If you ever went to a Billy Graham rally back then, you were changed forever. There’s never been a preacher like him. … I saw Billy Graham in the flesh and heard him loud and clear.”

U2 lead singer Bono wrote a poem for the Grahams. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Although he is most well-known for his relationships with politicians, straight-and-narrow Graham was best of friends with Johnny Cash, the blue-collar troubadour who, when they met in 1969, was making headlines for recording live albums in Folsom State and San Quentin prisons. The Grahams and Cashs grew to be very close. Not only did Johnny and June Cash perform at Graham rallies, but Billy and Ruth joined the Cash family on numerous vacation outings.

“I’ve always been able to share my secrets and problems with Billy, and I’ve benefited greatly from his support and advice,” Cash wrote in his autobiography. “Even during my worst times, when I’ve fallen back into using pills of one sort or another, he’s maintained his friendship with me and given me his ear and advice, always based solidly on the Bible. He’s never pressed me when I’ve been in trouble; he’s waited for me to reveal myself, and then he’s helped me as much as he can.”

Despite what some perceived as a squeaky-clean piety that gravitated to the halls of power, Graham had a deep and abiding love for the outsiders and the spiritual searchers. “It was eleven o’clock on a Sunday morning, but I was most definitely not in church,” Graham wrote in his autobiography Just As I Am. “Instead, to the horror of some, I was attending the 1969 Miami Rock Music Festival.” Preaching from the same concert stage as Canned Heat, the Grateful Dead, and Santana, Graham wrote about his delight to speak to “young people who probably would have felt uncomfortable in the average church, and yet whose searching questions about life and sharp protests against society’s values echoed from almost every song.”

Graham actually donned a disguise to get a feel for the festival the night before he would preach. “My heart went out to them,” he wrote. “Though I was thankful for their youthful exuberance, I was burdened by their spiritual searching and emptiness.”

Although Graham was prepared to be “shouted down,” he was “greeted with scattered applause. Most listened politely as I spoke.” He told them that he had been listening carefully to their music: “We reject your materialism, it seemed to proclaim, and we want something of the soul.” Graham proclaimed that “Jesus was a nonconformist” and the he could “fill their souls and give them meaning and purpose in life.” As they waited for the upcoming bands, Graham’s message was, “Tune in to God today, and let Him give you faith. Turn on to His power.”

Graham’s well-known message also did not hinder his ability to reach beyond evangelical boundaries. He longed for improved relationships between Roman Catholics and Protestants and was a trusted friend of Catholic television pioneer Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. “We are brothers,” Pope John Paul II told Graham during a visit to the Vatican.

In 1979, the late Muhammad Ali, three-time world heavyweight boxing champion, spent several hours with Graham in the evangelist’s home in North Carolina. “When I arrived at the airport, Mr. Graham himself was waiting for me. I expected to be chauffeured in a Rolls Royce or at least a Mercedes, but we got in his Oldsmobile and he drove it himself,” Ali recalled. “I couldn’t believe he came to the airport driving his own car. When we approached his home I thought he would live on a thousand acre farm and we drove up to his house made of logs. No mansion with crystal chandeliers and gold carpets, it was the kind of house a man of God would live in. I look up to him.”

Ali told the press, “I’ve always admired Mr. Graham, I’m a Muslim and he’s a Christian, but there is so much truth in the message he gives, Americanism, repentance, things about government and country – and truth. I always said if I was a Christian, I’d want to be a Christian like him.”

Generations later, Graham’s magnetism never weakened. One month after the Irish band U2 played an unforgettably emotional halftime show at the Super Bowl in 2002 memorializing the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Bono responded to an invitation to visit the Grahams at their home. Inside a collection of the work of Irish poet Seamus Heaney given to Ruth and Billy, Bono had written a poem that refers to “the voice of a preacher/loudly soft on my tears” which was the “lyric voice that gave my life/A Rhyme/a meaning that wasn’t there before.” The poem is on display at the Billy Graham Library in North Carolina.

In a touching tribute to Graham three years later, Bono said: “At a time when religion seems so often to get in the way of God’s work with its shopping mall sales pitch and its bumper sticker reductionism, I give thanks just for the sanity of Billy Graham – for that clear empathetic voice of his in that southern accent, part poet, part preacher – a singer of the human spirit, I’d say. Ah, yeah I give thanks for Billy Graham.”

Billy Graham preaches in the 1950s. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Evangelistic energy. In addition to calling men, women, and children – rich and poor, black and white, powerful and humble – all over the globe to a commitment to Christ, Graham was also reminding the institutional church of the foundational need to share the faith. In 1976, his efforts were recognized by the United Methodist Association of Evangelists as one of the earliest recipients of the Philip Award. Four years later, he preached at the denomination’s Congress on Evangelism on the campus of Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“Many have moved from a belief in man’s personal responsibility before God to an entirely new concept that assumes all men and women are already saved,” said Graham in 1980. “There’s a spreading universalism, which has deadened our urgency that was had by John and Charles Wesley, Francis Asbury, E. Stanley Jones, and others like them.

“This new evangelism leads many to reject the idea of conversion in its historical Biblical meaning and the meaning historically held and preached and taught by the Methodist Church.”

Graham concluded his remarks by quoting Methodist leader John Wesley in 1784: “You have nothing to do but to save souls, therefore spend and be spent in this work.” He continued to quote Wesley, “It is not your business to preach so many times and to take care of this or that society; but to save as many souls as you can; to bring as many sinners as you possibly can to repentance and with all your power to build them up in that holiness, without which they will never see the Lord.”

Graham reminded the participants of their heritage. “Let it be remembered that the Methodist church began in the white peak of conversion and intense evangelistic energy,” he said. “Let it be recalled that the Methodist church is an evangelistic movement.”

Good News connection. More than a decade before his address at the Congress on Evangelism, Graham’s preaching played a key role in the conversion of Good News’ founding editor Charles Keysor. The evangelist’s encouragement was also an important inspiration during the ministry’s formative years.

“I have always believed that The United Methodist Church offers tremendous potential as a starting place for a great revival of Biblical Christian faith,” Graham wrote in a personal note of encouragement to the staff and board of directors on the occasion of the 10-year anniversary of Good News. “Around the world, millions of people do not know Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord, and I believe that The United Methodist Church, with its great size and its honorable evangelistic tradition, can be mightily used by God for reaching these lost millions,” wrote Graham in 1977.

“I have been acquainted with the Good News movement and some of its leaders since 1967. To me it represents one of the encouraging signs for the church fulfilling its evangelistic mission, under the Bible’s authority and the leadership of the Holy Spirit. At the forefront of the Good News movement has been Good News magazine. For 10 years it has spoken clearly and prophetically for Scriptural Christianity and renewal in the church. It should be read by every United Methodist.”

Everyone associated with Good News in that era – and subsequent generations – found great inspiration in Graham’s words.

The message and the man. “Billy Graham’s ministry taught me to step out in faith and trust God in all things in my life,” Dr. Timothy C. Tennent, president of Asbury Theological Seminary, said in a statement after attending Graham’s funeral in North Carolina.

“After preaching in Red Square in what was then the Soviet Union, Billy Graham stopped at Gordon Conwell, where I was a student. Someone asked Mr. Graham if he had been used as part of Soviet propaganda. He replied that he had preached the same Gospel in Red Square as he did around the world. This taught me not to worry about the discouraging naysayers and critics in my ministry. Even Billy Graham’s funeral continued to teach us about the grace and glory of God.”

There was one testimony of poignant grace at Graham’s funeral that caught the attention of the Rev. Dr. Maxie Dunnam, former World Editor of The Upper Room and evangelical United Methodist leader. “The most meaningful for me was the sharing of one daughter who had a painful marriage that ended in divorce,” he recalled. “She spoke about her shame and how dreadful it was to think of how this was affecting her Mom and Dad, but how redemptive it was when she was welcomed home by Billy with open arms.”

“It was a powerful prodigal daughter story. There was no pretension of perfection,” Dunnam said. “The feeling was that we were at a large family funeral, friends gathered to remember, to share their grief and celebrate the life of a loved one. Again, the emphasis was not on the man but the message.”

When speaking about the end of his own life, Graham used to like to paraphrase the words of one of his heroes, D. L. Moody, an evangelist of a different era: “Someday you will read or hear that Billy Graham is dead. Don’t you believe a word of it. I shall be more alive than I am now. I will just have changed my address. I will have gone into the presence of God.”

Graham’s admirers note the change of address with deep respect and love.

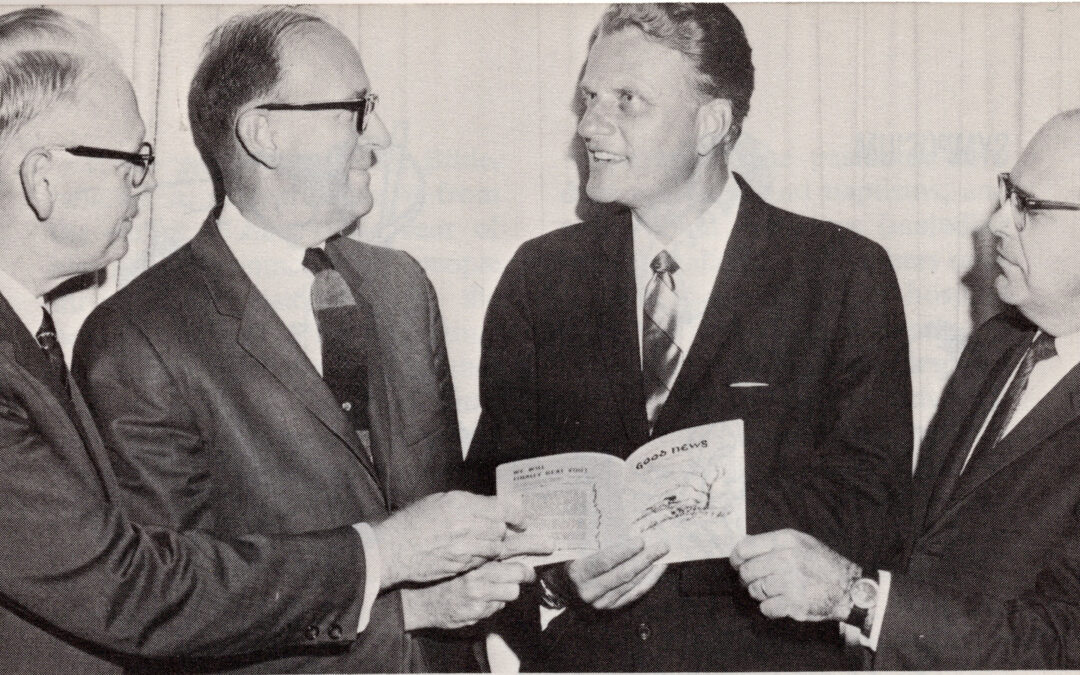

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Opening photo: Billy Graham discusses the second issue of Good News with (left to right) Dr. Frank Stanger, president of Asbury Theological Seminary; the Rev. Philip Worth, United Methodist pastor and chairman of the Good News board of directors; and Dr. Charles Keysor, founder of Good News.

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Witness to Hope

By Steve Beard –

January/February 2017

Looking back upon the 1960s, Good News was launched in an era bookended by the smoking barrels of assassin rifles, the fleeting banter of “God is dead” dogma, a Cuban missile crisis, attack dogs lunging at civil rights protesters, flower children, Cassius Clay becoming Muhammed Ali, the Bible read from space, a six day war, and The Who destroying their instruments on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour television show.

The decade was anything but uneventful.

President John F. Kennedy, a Roman Catholic, was assassinated in 1963 on the same day as the death of Anglican layman C.S. Lewis, author of Mere Christianity and The Chronicles of Narnia. Strangely enough, it was also the day of the passing of Aldous Huxley, author of a Brave New World.

In 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Two months later Senator Robert Kennedy died in the Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles after being shot. The homicidal brutality and steely calculation of humanity’s original sin bared it fangs once again. It was a bloody decade – and not just for the famous and prophetic.

There was a reason that Timothy Leary simply said, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” With more meaningful contrition, however, the weathered bluesman would simply say, “Lord, have mercy.” The cultural mavens of that decade were trying to juggle the adrenaline of the counterculture, civil rights and race relations, budding feminism and women’s liberation, new immigration standards, the influx of alternative religions, and American young men dying in Vietnam.

The world was a chaotic place at the time. It probably always has been, but it seemed to be especially strung out and anxious. No wonder Andy Warhol turned a familiar and comforting symbol like a Campbell’s tomato soup can into a pop culture icon.

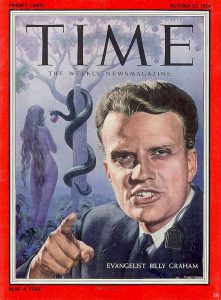

Modern, secular man. Charles Keysor was a journalist who had his life flipped upside down at a Billy Graham crusade. Although he was a church-going Methodist, Keysor was a modern, secular man – self-described as “self-sufficient, agnostic, ambitious, materialistic, and seen in church mostly at his wife’s urging.” Nevertheless, he would lay awake at night wondering if there was more to life than a good paycheck, a nice house in the country, and professional success. “I had heard about Jesus,” Keysor would admit. “But as I reached my mid-30s I could see no connection between His perfect life and my struggles; between His death on the cross and my growing inner confusion.” Where was a man supposed to find hope?

On business trips, he would dip into the Gideon Bible in his hotel room. “Jesus seemed to know me better than I knew myself,” Keysor said. “I desperately wanted a new and better life.” He responded to the invitation at a Graham crusade, “believing that Jesus could work a miracle if I gave myself to him.” Surrender. Forgiveness. Conversion. New life.

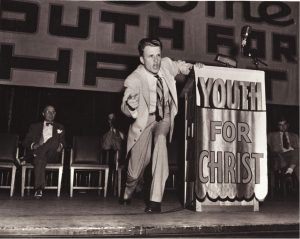

Graham represented a different spiritual and cultural strand during the 1960s – one that included preachers on television such Rex Humbard, Kathyrn Kuhlman, Oral Roberts, gospel singers such as Jake Hess and the Statesmen Quartet, The Staples Singers, The Dixie Hummingbirds, and ministries such as Teen Challenge, Campus Crusade for Christ, Youth With A Mission (YWAM), and InterVarsity.

For Keysor, it was the commitment made at a revival that opened his heart – with all the fear and trepidation of making a counterintuitive career shift – to going to seminary and becoming a clergyman. He graduated from Garrett Theological Seminary in 1965, was ordained, and appointed to Grace Methodist Church in Elgin, Illinois – his home church, northwest of Chicago.

While he was working his way through seminary, theologians and philosophers were attempting to find ways to eradicate what they perceived as outmoded and traditionalist concepts of God and cobble together a new secular theology for up-to-date sensibilities. In 1961, Protestant theologian Gabriel Vanhanian made a splash with his provocatively titled The Death of God: The Culture of our Post-Christian Era. Five years later, William Hamilton and Thomas Altizer published Radical Theology and the Death of God. There were other writers of this era spinning a similar yarn. Like students dissecting a formaldehyde-drenched frog in high school biology class, theologians were pretending to slice open the chest of God to see if the heart was still beating.

As a journalist and seminarian, Keysor had been fully exposed to all the varieties of eclectic, faddish theologies and alternative religions. None of those academic contrivances, however, had changed Keysor’s heart or given him the answers to the questions surrounding his purpose in life. The experience of turning his soul, mind, and career path over to Jesus Christ rang truer to him than did the trendy notions of theologians who had become bored or exasperated with orthodoxy.

In 1966, Keysor was invited by Dr. Jim Wall, editor of the Christian Advocate, to publish an affirmation of the beliefs of Methodist evangelicals. Entitled “Methodism’s Silent Minority,” Keysor made a spirited defense of the elementary Christian basics: the inspiration of Scripture, the virgin birth, the substitutionary atonement of Christ, the physical resurrection of Christ, and the return of Christ. Of course, there was nothing revolutionary in what Keysor had affirmed. It was all found in our Articles of Religion. The stir that was created is that Keysor affirmed it sober – without a wink, without his fingers crossed.

The “Silent Minority” article hit the streets only a few months after Time religion editor John Elson wrote a lengthy cover story with the sucker-punch title “Is God Dead?” In addition to the 3,421 letters from Time readers, the title stirred up a tsunami of a national debate about God, faith, and culture.

In response to his own article, Keysor was also flooded with letters and long distance phone calls (a big deal back then) from Methodist preachers. Almost all told him the same thing: “Thanks for speaking up! I didn’t think anybody else believed the way I do.” A few of the writers and callers asked Keysor about starting a magazine to reflect their point of view.

Demonstrate a way. Two years before Keysor’s article, Bishop Gerald Kennedy of Los Angeles presented the Episcopal Address at the 1964 General Conference of the Methodist Church. “Kennedy is unquestionably among the four or five most dazzling preachers in the U.S. today — an oratorical genius with a commanding baritone, and the pace and timing of a Broadway pro,” wrote Time magazine in a cover story on Methodism’s identity crisis a week after the General Conference.

“This year many of the 858 Methodist delegates arrived at their conference with the deep conviction that their church had reached a turning point in history,” reported Time, “and with a scarcely concealed fear that the vitality that once burned in Methodism was lost when fiery evangelism gave way to today’s organized, institutional church.”

In his address, Kennedy told the delegates that the Christian task is “to pursue our ancient course of attacking our own imperfections, keeping our life open to God, and perfecting our society. We are not trying to sell a system, but to demonstrate a Way which is incomparably better than all others, and shines with the promise of a more abundant life for all men.”

Kennedy was surefooted; appreciated by conservatives and liberals alike. Although not narrowly categorized as an evangelical, he was the high-profile chair of Billy Graham’s three week crusade in Los Angeles in 1963 (final evening attendance of more than 134,000).

At that time, Kennedy was spearheading the fastest-growing area of the Methodist Church. It was a golden era of buying property, building churches, and extending the tent pegs of Wesleyan Christianity on the West Coast.

Cornering Kennedy. Shortly after a speaking engagement in Chicago, Bishop Kennedy got cornered by Keysor. The persistent journalist spelled out the plan for Good News magazine. “That sounds great,” said Kennedy, “Let me know if I can help.” The next day Keysor asked him to write an article for the launch issue about the place of evangelicals in The Methodist Church.

Landing Kennedy in the first issue of Good News in 1967 illustrated Keysor’s tenacity as much as it revealed Kennedy’s authentic inclusivity and respect for evangelicals.

“It must be said that there is no question in my mind as to their [evangelicals] being a legitimate part of the Methodist heritage,” wrote Kennedy. “They are Wesleyan in their basic propositions. Their emphasis on conversion finds an echo on nearly every page of John Wesley’s Journal. The truth seems to me to be that The Methodist Church has been, broadly speaking, evangelical in its understanding and interpretation from the beginning.”

Kennedy had had run-ins with both closed-minded liberals and irascible fundamentalists. Although the power structure of the Methodist Church was unapologetically reflective of the liberalism of the era, Kennedy believed in a beefy pluralism that included orthodox believers, especially the “brethren whose emphasis is on the unchanging and eternal verities of our faith.” At a time when evangelicals felt like unwanted third-cousins, Kennedy’s affirmation went a long way when he wrote that they “are just as legitimately Methodists as are these brethren who look down their noses at them and consider them outmoded.”

Of course, we live in a different era. A lot has changed in 50 years. There may be a temptation to view some of Kennedy’s words as less dramatic than they appeared in that first issue of Good News in 1967. Although Methodism appeared rich and strong, we had deep and painful fissures – not only with race, but also with theology, spirituality, and ideology. Kennedy’s words of inclusion were important.

Along these lines, there were two major events that took place in between Keysor’s “Silent Minority” article and the first issue of Good News that made Kennedy’s olive branch extension all the more significant.

• British believers gathered on October 18, 1966, for the National Assembly of Evangelicals in London to discuss theology, ecumenism, and unity. Before 1000 delegates, the two most well-known evangelical leaders – the Rev. Dr. Martyn Lloyd-Jones of Westminster Chapel and the Rev. Dr. John Stott of All Souls Church – had a major public rift about whether evangelicals should remain or withdraw from the Church of England. Lloyd-Jones argued that evangelicals are “scattered about in the various major denominations … weak and ineffective.” Stott, an Anglican, took umbrage and used his position as the chair of the event to fire back with animated rhetoric at Lloyd-Jones, his ministerial colleague and friend.

• One week later, The World Congress on Evangelism was sponsored in Berlin by Billy Graham and Dr. Carl F. H. Henry, founding editor of Christianity Today. The conference drew leaders from 60 denominations. “We discovered that we were all needy sinners – all alike before God in both our inadequacy and our unrealized potential,” said the Rev. Mike Walker, a Methodist pastor from Texas and Good News board member, in his report from Berlin in the first issue of Good News.

According to the New York Times reporting, there was discussion among the international delegates to starting a “new denomination or withdrawing from the central bodies of existing ones.” Henry is quoted as saying that evangelicals should “stay where they are and resummon their denominational brethren to the major task of the church, preaching the Gospel.”

This was, quite simply, part of the Good News vision.

God is not dead. For fifty years, Good News has faithfully worked within The United Methodist Church because people like Chuck Keysor believed God could offer renewed spiritual life to men, women, and children. “Orthodox Methodists come in theologically assorted shapes, sizes, and colors,” wrote Keysor in his “Silent Minority” article. “But, unfortunately, the richness and subtlety of orthodox thought are often overlooked and/or misunderstood. There lurks in many a Methodist mind a deep intolerance toward the silent minority who are orthodox. This is something of a paradox, because this unbrotherly spirit abounds at a time when Methodism is talking much about ecumenicity — which means openness toward those whose beliefs and traditions may differ.”

Good News has always believed evangelicals, conservatives, moderates, and traditionalists have an essential role within The United Methodist Church – and we wanted to make it a more faithful denomination by supporting missions and publishing trustworthy confirmation materials and Sunday school curriculum.

More importantly than anything else, we wanted Good News magazine to reflect our witness for the life-changing message of Christ with grace and truth. Jesus is the Good News – we are merely a movement and a magazine.

In the height of the “God is dead” hype, the Rev. Dr. James Cleveland, known as the King of Gospel Music, recorded a two-album set in Cincinnati featuring a pew-jumping rendition of “God Is Not Dead.” In the same year, Tennessee Ernie Ford released his album “God Lives!,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe played her sanctified blues at the Newport Folk Festival, Mahalia Jackson recorded “There is a Balm in Gilead” on an Easter Sunday album, and Elvis released his album “How Great Thou Art.”

“One reason for the persistence of gospel music is the people’s persistent interest in the Gospel,” observed Keysor in his “Silent Minority” article. In other words, listen to the singers and gospel choirs. Let their light shine. Let them play their part.

That is what Good News has wanted to do for the last 50 years – play our part. Keysor called it our “journalistic ‘mission’ to Methodism’s ‘silent minority.’” We remain grateful to God for this opportunity and to the men and women who sacrifice, contribute, and pray for us to press forward in our mission to see a renewed United Methodist Church.

In his Good News article, Bishop Kennedy wrote, “A great deal of this modern spirit is a passing thing, and after we have changed our minds a hundred times in the future, the great and fundamental truths of our religion will shine forth with continuing brilliance. With all the modern talk about Church having to keep up to date, it is great to have clear voices proclaiming that over against all the novelties there is the unchanging truth of what God has done for us through the Incarnation.”

It remains our vision to be a witness to hope for a life-transforming United Methodism and a clear voice that allows the continuing brilliance of our Lord and Savior to shine through the pages of Good News.

Marking his 25th year, Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Photo: Dr. Frank Stanger, president of Asbury Theological Seminary; the Rev. Philip Worth, United Methodist pastor and chairman of the Good News Board of Directors; Billy Graham, and Dr. Charles Keysor, founder of Good News, discuss the second issue.

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Archive: The Making of a Movement

The Rev. Dr. Charles Keysor at the offices of Good News.

By James V. Heidinger II-

The Rev. Charles W. Keysor, a Methodist pastor in Elgin, Illinois, published the first issue of a digest-size magazine for Methodist evangelicals out of the basement of his parsonage in 1967. At the suggestion of his wife, Marge, he called it Good News.

It had all begun a year earlier when James Wall, then editor of the Methodist minister’s magazine Christian Advocate, asked Chuck, “Why don’t you write an article for us describing the central beliefs and convictions of this part [evangelical wing] of our church?”

Chuck’s article, “Methodism’s Silent Minority” was published in the July 14, 1966 issue of the Christian Advocate, where he identified the major evangelical convictions (see original article on p. 12).

To his amazement Keysor received over 200 letters and phone calls in response to his article, most of them coming from Methodist pastors! Two themes surfaced in the responses: first, “I thought I was the only one left in the church who believes these things,” and second, “I feel so alone — so cut off from the leadership of my church.”

As he prayed about the letters and phone calls, Chuck felt he must do something. Having been a journalist prior to entering the ministry, he decided to launch a magazine which affirmed the evangelical message of the Wesleys and Francis Asbury. Good News magazine was born.

Responses to the first issue were much like today. One disgruntled Methodist in Alabama wrote, “Your magazine is JUNK!” But Dr. Carl F. H. Henry, founding editor of the evangelical journal Christianity Today, wrote, “A mighty fine beginning — congratulations!”

Rallying renewal groups: Seeing the immediate surge of interest in his magazine, Keysor chose 12 Methodists to serve as board members, and the Good News effort became incorporated as “A Forum for Scriptural Christianity.” The board’s first meeting was in May of 1967, only two months after the appearance of the first issue of the magazine.

Good News was a breath of fresh air for Methodists seeking spiritual renewal, quickly becoming their rallying point. Pastors and laity began organizing clusters of like-minded Methodists who came out of a felt need for fellowship, support, encouragement, and prayer. Soon, they began to map strategies for increasing evangelicalism within their annual conferences. Today, renewal groups exist in many United Methodist annual conferences, forming an extensive grassroots network for evangelical advocacy, fellowship, and prayer support.

Convo fellowship: The Good News board soon felt a need to sponsor a national gathering to help unify Methodist evangelicals. The Rev. Mike Walker, a pastor from Texas and the youngest member of the fledgling board, headed up plans for the first national convocation held in Dallas in August 1970. To everyone’s amazement, a whopping 1,600 United Methodists registered, coming from coast to coast! The Holy Spirit drew people together in a remarkable way.

Emotion and excitement filled the air as participants discovered other like-minded Methodists. Tears streamed down the faces of worshippers as they saw the evening crowds swell to nearly 3,000 persons jammed into the Adolphus Hotel ballroom. Folks heard luminaries such as author and missionary statesman Dr. E. Stanley Jones (Christian Ashram), Bishop Gerald Kennedy (Southern California), Dr. Frank B. Stanger (Asbury Theological Seminary), Dr. Dennis F. Kinlaw (Asbury College), Dr. K. Morgan Edwards (Claremont School of Theology), Dr. Claude Thompson (Candler School of Theology), the Rev. Tom Skinner (author and evangelist from Harlem), the Rev. Howard Ball (Campus Crusade for Christ), the Rev. Dr. Akbar Abdul-Haqq (evangelist with the Billy Graham Association), the Rev. Dr. Ira Gallaway (district superintendent of Fort Worth), the Rev. C. Philip Hinerman (Park Avenue United Methodist Church in Minneapolis), and the Rev. Dr. Les Woodson (Elizabethtown, Kentucky).

In bringing greetings to the assembly, a message from evangelist Billy Graham stated: “Wish I could be with you for this momentous and historic conference. Methodism was born and it grew through revival and evangelism. It is my prayer that the United Methodist Church will have a spiritual renewal and help lead our nation in the spiritual revival that we so desperately need. May God bless you all.”

Twentieth century United Methodism was marked for renewal. Discouraged United Methodists received hope that they weren’t alone in their evangelical concerns. And most importantly, they began to dream of a new day of revival and renewal in their church. For 30 years following the Dallas Convocation, Good News sponsored a national convocation nearly every summer. United Methodists came for fellowship, inspiration, and instruction.

Improving Sunday school literature: One of the earliest concerns of the fledgling Good News movement was the need to improve dismal denominational Sunday school literature. Evangelicals were frustrated, but hardly knew where to begin to bring about change.

In 1968 Good News carried a stinging evaluation of Methodism’s new adult curriculum. One reviewer wrote, “What is missing here … is a particular and sustained biblical theology.” This reviewer looked in vain for any word about “salvation, any good news about the atonement of Jesus Christ, or any hint about the possibility of spiritual new birth….”

The next year a Good News team met for the first of many dialogues with the church’s curriculum editors and officials. The denominational leaders responded with obvious impatience and condescension toward evangelical concerns. One bishop informed the Good News delegation that they must realize that all contemporary scholars supported the Bultmannian notion that much of the Bible is myth. That was indicative of the gulf that existed between grassroots members and many in positions of national leadership.

Nevertheless, dialogue had begun. The United Methodist Publishing House gradually became more aware of its responsibility to serve the whole church, including the evangelicals. In 1975, Good News published its first edition of We Believe, a confirmation series for junior high youth. Pastors dissatisfied with United Methodist materials received it enthusiastically. It remains a widely-used confirmation curriculum yet today.

A 1985 evaluation of denominational curriculum revealed improvement in our church school literature. In addition, the Disciple Bible Study program has found a warm welcome in the church, as has more recently Christian Believer, a similarly-packaged in-depth study of Christian doctrine, a resource from the United Methodist Publishing House (UMPH) which is doctrinally sound.

The problem evangelicals had with church school curriculum was its lack of consistency. For adults especially, one quarter’s materials might be sound while the

Dr. E. Stanley Jones

next were disappointingly weak, which is the problem with materials that are published for a broad sweep of theological positions. This inconsistency, among other things, was the impetus that led Good News to begin publishing its Wesleyan and evangelical Bristol Bible Curriculum for many years, as well as Trinity Bible Studies and We Believe confirmation material.

Through its book and curriculum publishing endeavor, Good News exercised its heartfelt desire to provide theologically orthodox and biblically-based resources to United Methodists. In addition to the Wesleyan curriculum, the initial book titles included Basic United Methodist Beliefs written by a team of evangelical scholars and theologians and The Problem with Pluralism: Recovering United Methodist Identity written by Dr. Jerry Walls, noted philosopher and theologian.

Until most recently, both the We Believe confirmation materials and the Bristol Bible Curriculum were published by the independent, for-profit publisher, Bristol House, Ltd., headquartered in Georgia. (Good News sold its publishing ministry in 1991 to a small group of Good News supporters – that included Dr. John and Helen Rhea Stumbo, a lifetime Good News board member and current chairperson of our board of directors – who formed Bristol House, Ltd. in order to continue the publishing endeavor.)

Doctrinal doldrums: From the start, Good News’ primary concern has been theological. Born in an era when church radicals were demanding “Let the world set the agenda for the church,” we were convinced that the biblical agenda was languishing from both neglect and from theological revisionism.

Adding to United Methodism’s already-existing theological malaise, the 1972 General Conference adopted a new doctrinal statement of “theological pluralism.” While pluralism may have been included to express some of the legitimate diversity found within the parameters of historic Christianity, it was interpreted by many to mean United Methodism offered members a proliferation of theological views, many of which far exceeded the boundaries of sound biblical doctrine.

A young pastor friend of mine was distressed because a United Methodist seminary professor had denied the bodily resurrection of our Lord. He expressed his concern about the matter in his church newsletter. His district superintendent admonished him, saying, “Ed, you must remember that you are in a church that embraces theological pluralism.” For that superintendent, theological pluralism meant that some may affirm the bodily resurrection of Christ and some may not.

In 1974, Good News authorized a “Theology and Doctrine Task Force,” headed by Paul Mickey, who at that time was associate professor of pastoral theology at Duke University’s Divinity School. The task force was charged with preparing a fresh, new statement of “Scriptural Christianity” which would remain faithful to both the Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren traditions. In addition to Mickey, the committee included myself, Charles Keysor, Frank B. Stanger, Dennis F. Kinlaw, Robert Stamps, and Lawrence Souder.

In 1975, the Task Force presented its statement to the Good News board and it was adopted at its summer meeting at Lake Junaluska. It thus became known as “The Junaluska Affirmation.” To its credit, The United Methodist Reporter published the affirmation in full and provided commentary. Dr. Albert Outler, United Methodism’s eminent theologian, praised Good News at the time for being perhaps the only group within the church to respond to his challenge for United Methodists to “do theology.”

Theological issues were always top drawer for Good News. Our questions and frequent criticism of theological pluralism played a major role in the 1984 General Conference decision to develop a new doctrinal statement for the church. The theological commission, authorized by that General Conference and chaired by Bishop Earl G. Hunt Jr., brought a new and much improved theological statement which was adopted overwhelmingly by the 1988 General Conference. It cited “the primacy of Scripture” as the new guiding principle for doing theology.

The term “theological pluralism” was purposefully and conspicuously omitted from the new statement. Some today still try to resuscitate “theological pluralism” under the guise of diversity. However, United Methodism has its clearly articulated doctrinal standards which are protected by Restrictive Rule in the Book of Discipline (Par. 17. Article I).

The seminary challenge: Good News has long been troubled over the liberal domination of theological education. Across the years, evangelicals at our United Methodist seminaries have consistently reported unfair caricaturing, ridicule, and intolerance toward their orthodox, biblical beliefs. They also have cited a troubling dearth of evangelical faculty at our seminaries.

In 1975, United Methodist evangelist Ed Robb Jr., in a fiery address at Good News’ summer convocation, called upon the church to restore Wesleyan doctrine to our United Methodist seminaries. Institutional leaders fumed and seminary professors fussed about his challenge. One could hear the murmurs echoing from their hallowed halls: “How dare he be so critical!”

However, Robb’s hard-hitting address led to a new friendship with Dr. Outler who taught at Perkins School of Theology in Dallas. Together, with help from others, they formed A Foundation for Theological Education (AFTE). To date, more than 160 evangelical scholars, called John Wesley Fellows, have participated in the scholarship program, receiving grants to seek their PhDs with plans to return to teach at our United Methodist colleges and seminaries.

In 1976, Good News also began publishing Catalyst, the free newsletter sent to all United Methodist seminarians, with the goal of making them aware of evangelical scholarly resources which they did not always have in their liberal seminary setting. The Rev. Mike Walker, the board member who organized the first Good News convocation, has coordinated the editing and mailing of Catalyst from its inception. (It continues today under the auspices of AFTE.)

In 1977, Good News sent teams to nearly all United Methodist-related seminaries, engaging them in dialogue and urging them toward greater openness to evangelical faculty, course materials, and library resources.

Evangelist Ed Robb Jr.

Missions derailed: In 1974, United Methodist evangelicals from 23 states gathered in Dallas to discuss their concerns with the church’s world missions program. Those gathered criticized the declining number of overseas missionaries, the mission board’s preoccupation with social and political matters, and its lack of concern for matters of faith — including conversion and the planting of new churches.

The group formed the Evangelical Missions Council (EMC) which several years later would become an arm of Good News. Dr. David A. Seamands, Good News board member and former missionary to India, was named EMC’s first chairman. Conversations with the General Board of Global Ministries (GBGM) continued. However, after no less than 22 “dialogues” over an 11-year period between Good News and GBGM, Seamands, and others learned that “the unfortunate gulf separating us from the GBGM policymakers was wide and deep.”

For eight years, the Rev. Virgil Maybray, a highly-respected clergy member of the Western Pennsylvania Annual Conference, served as full-time executive secretary of Good News’ EMC effort, spending most of his time speaking in, and consulting with, local churches about expanding their missions programs. During that time, Virgil ministered in more than 350 UM churches in 35 states, raising millions of dollars for missions, with more than $1 million channeled directly through GBGM’s Advance Special Programs.

In 1983, when evangelical discontent peaked upon learning about the proposed new leadership of the World Division of GBGM, 29 large-church pastors and 4 missions professors (all United Methodist) met in St. Louis to form a “supplemental” missions sending agency. It was to be called The Mission Society for United Methodists. It opened its doors for ministry in February of 1984 and began helping United Methodists get to the mission field. Today, with headquarters in Norcross, Georgia, and now known as simply TMS Global, the sending agency now has 180 persons in ministry (full-time, standard support) in 35 countries.

Legislative landmarks: United Methodist evangelicals and traditionalists have struggled with how to respond to the church’s liberal theologies and programs. They could ignore them, find another church, or use their influence for positive change. Good News opted for the latter.

At the 1972 General Conference in Atlanta, Good News launched its first involvement in the legislative process. Board members Bob Sprinkle and Helen Rhea Stumbo prepared and distributed ten petitions and four resolutions. They also cranked out occasional newsletters. Although the 1972 conference was a disaster, approving abortion and adopting the statement on theological pluralism, Good News had thrown its hat in the ring.

The 1976 General Conference brought a stronger Good News showing with the additional help of the Revs. Robert Snyder and John Grenfell. By 1980, Good

Rev Virgil Maybray

News had launched its first full-orbed effort, led by Don and Virginia Shell. They continued leading Good News’ legislative strategy program until 1992, when they turned the leadership over to Lynda and Scott Field, a former Good News board chair and United Methodist clergy person in the Northern Illinois Annual Conference. They gave extraordinary leadership to the Good News General Conference effort from 1996 through 2004. The legistlative baton for General Conference has been handed over to the Rev. Thomas Lambrecht, the vice president of Good News, and to his capable leadership of the Reform and Renewal Coalition.

The Good News effort has worked behind the scenes in annual conferences to get evangelical and traditional delegates elected as General Conference and Jurisdictional delegates, well-crafted petitions channeled properly, and a series of position papers published which articulate our stand on major issues.

The nearly two weeks Good News spends on site at General Conference with our 40-person team is the culmination of more than two years of careful preparation. As a result of Good News’ field work and legislative training efforts, many more United Methodist evangelicals became involved in the legislative process.

Traditionalist believers were encouraged by the efforts of concerned denominational leaders to formulate pre-General Conference activity such as the 1988 “Houston Declaration” and the 1992 “Memphis Declaration.” Both of these initiatives were spearheaded by the leadership of what is now known as the Confessing Movement within the United Methodist Church — which included Bishop William Cannon and prominent pastoral leaders such as James B. Buskirk, Maxie D. Dunnam, Ira Gallaway, John Ed Mathison, Thomas C. Oden, William Bouknight, and William H. Hinson. The grassroots efforts noted above reflected the growing conviction that evangelicals must engage in the legislative process to make their voices heard if the church is ever to experience renewal and reform.

Proliferation of evangelical voices: It is amazing that at one time – 50 years ago – there were no groups or publications that spoke on behalf of United Methodism’s evangelical or conservative constituency. That, no doubt, helps explain the immediate flood of responses to Chuck Keysor’s inaugural article, “Methodism’s Silent Minority.”

It’s a different world today and The United Methodist Church is not the same church. Think of the organizations that didn’t exist in 1966: Good News; United Methodist Action, a division of The Institute on Religion and Democracy; The Confessing Movement, A Foundation for Theological Education, The Mission Society, Transforming Congregations, Lifewatch (the Taskforce of United Methodists on Abortion and Sexuality), the Renew Network, Seedbed, and Concerned Methodists.

We should also note the important contribution of several groups affiliated with the General Board of Discipleship, including the Council on Evangelism, the Foundation for Evangelism, the National Association of UM Evangelists, and Aldersgate Renewal Ministries. The above groups have been faithful voices on behalf of our Wesleyan theological heritage.

All of these groups, of course, have their own histories and purposes. They do not walk in lockstep, to be sure. But let’s not miss the significance of their existence. The voices of United Methodist evangelicals and traditionalists are finally being heard. Thousands of United Methodists have found avenues for evangelical ministry as well as ways to effectively address the spiritual, moral, theological, and social issues that exist in our church.

Emerging new spirit: The various evangelical groups noted above are a part of something new that is emerging within the United Methodist Church. I would call this new surge a growing expectation that the church be faithful to its historic message. More and more United Methodists have grown weary of theological revisionism and doctrinal fads; weary of those who would use the church in order to advance an ideological agenda. It is time for all of our United Methodist leaders to embrace, believe, and teach the historic doctrines of our Wesleyan tradition.

We are especially excited about the proposal for starting new congregations all across the country. Evangelism has always been a passion for the Good News constituency. For many years, Good News magazine was a promotional partner with The Alpha Course. By their account, our involvement was a major factor in Alpha being used in more United Methodist churches than any other denomination in America.

Cry for leadership: When United Methodists feel compelled to form alternative groups within the church and gather at their own expense to issue declarations to the church – as they did at Houston and Memphis and, most recently in, Chicago – what you have is a plea for godly leadership. We look hopefully to our bishops who are charged with the teaching and overseeing function in the church. Our bishops, according to Paul, “must hold firmly to the trustworthy message as it has been taught,” so they can “encourage others by sound doctrine and refute those who oppose it” (Titus 1:9).

It is easy for evangelicals to grow weary in the struggle for renewal. Some who do will often say, “The struggle is a distraction from the real ministry of the church.” But Presbyterian clergywoman, the Rev. Sue Cyre, former editor of the journal Theology Matters, has written an apt reply: “The battle over truth and falsehood is the real ministry of the church,” writes Cyre. “Everywhere the church goes, it is to proclaim the truth of the Gospel, but it is always against a backdrop of some false beliefs.”

New day for United Methodism? So perhaps a new atmosphere is emerging within the church. Granted, we still face serious problems, but there is much reason for hope.

As I have stated during my time as the president of Good News, evangelicals believe the church has been entrusted with a divinely-revealed plan of redemption. This message is set forth clearly in the Word of God. This fact automatically establishes the relevance of the Christian message. We must resist attempts to impose other standards of relevance upon it. The biblical message, proclaimed in the power of the Holy Spirit, will still bear fruit today. This trustworthy message will revitalize and renew United Methodism and enable us to share in the evangelical awakening that already is moving across our land and world. When our pulpits are alive again with the faithful proclamation of the Word of God, we can be sure the Lord will once again add daily to the United Methodist Church “those who are being saved.”

James V. Heidinger II is the publisher and president emeritus of Good News. Dr. Heidinger, a clergy member of the East Ohio Annual Conference, led Good News for 28 years until his retirement in 2009. He is the author of several books, including the forthcoming The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism (Seedbed).

by Steve | Jan 24, 2017 | Jan-Feb 2017, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Archive: Coming Out of Exile

Photo courtesy of Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. All rights reserved. www.billygraham.org.

By Riley Case-

The 1960s were not a good time for evangelicals. For one thing, the Methodist liberal establishment did not even want to admit evangelicals were evangelicals. When I went to the head of the chapel committee at my Methodist seminary and asked if we might be able to include some evangelicals among the chapel speakers, he informed me everyone at the seminary was evangelical, and just who did I have in mind. When I explained he replied, “I believe you are talking about fundamentalists and we’re not going to share our pulpit with any of them.”

When Billy Graham came to Chicago and some of us wanted to ask Graham to visit our campus, the president of the school said, “No, because we do not wish to be identified with that kind of Christianity.”

The prevailing seminary and liberal institutional view was that “fundamentalism” was an approach to Christianity of a former day and was not appropriate for Methodists, neither in the present day nor for the future. Methodism was set in its direction. In a survey of seminaries conducted in 1926, every single Methodist seminary had declared its orientation as “modernist.” As early as June 1926, the Christian Century had declared that the modernist-fundamentalist war was over and fundamentalism had lost. It announced its obituary in these words: “It is henceforth to be a disappearing quantity in American religious life, while our churches go on to larger issues.”

Other larger issues in the 1960s included war, race, COCU, economic disparity, Death of God, the Secular City, liberation theology, rising feminism, process theology, and existentialism.

Institutional liberalism was out of touch – and I was frequently bemused in those seminary days by how out of touch it was. When someone mentioned revivals in seminary, the professor indicated that revivals were a thing of the past and he had not heard of a Methodist church that had held a revival for years.

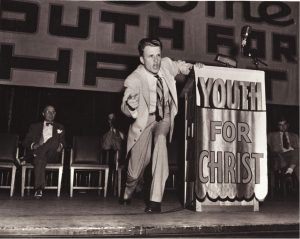

It so happened that a friend of mine from Taylor University days, Jay Kesler, was at that very moment holding a revival and would preach at 152 revivals during his years at college, most of them in Methodist churches. Youth for Christ was on the scene, as was Campus Crusade and Billy Graham’s ministry. Evangelical schools were flourishing.

That was the situation when Chuck Keysor, a pastor from Elgin, Illinois, wrote an article for the July 19, 1966 issue of the denomination-wide Christian Advocate entitled, “Methodism’s Silent Minority.”

“Within the Methodist church in the United States is a silent minority group,” Keysor wrote. “It is not represented in the higher councils of the church. Its members seem to have little influence in Nashville, Evanston, or on Riverside Drive. Its concepts are often abhorrent to Methodist officialdom at annual conference and national levels.

“I speak of those Methodists who are variously called ‘evangelicals’ or ‘conservatives’ or ‘fundamentalists.’ A more accurate description is ‘orthodox,’ for these brethren hold a traditional understanding of Christian faith.”

Keysor explained in the article that this minority was often accused of being narrow-minded, naïve, contentious, and potentially schismatic. This was unfortunate because these people loved the church and had been faithful Methodists all their lives.

In making his case Keysor mentioned that there were many more of them than official Methodism was counting. At least 10,000 churches, for example, were using Bible-based Sunday school material instead of the official Methodist material. The 10,000 figures brought strong reaction and led to charges of irresponsibility and plain out lying. But Keysor knew whereof he spoke.

Trained as a journalist he had served as managing editor of Together magazine, Methodism’s popular family magazine. He had then been converted in a Billy Graham crusade and spent some years as an editor at David C. Cook, an evangelical publisher. The 10,000 churches figure had come from his years at Cook. He knew more about what churches were not using Methodist materials than did the Nashville editors at the time. At Cook, he also became aware of the evangelical world.

Riley B. Case

Keysor’s article drew more responses than any other article Christian Advocate had ever published. The responses followed a common theme: “You have spoken our mind. We didn’t know there were others who believed like we did. What can we do?” Keysor called together some of the most enthusiastic responders. Hardly any of those early responders would be recognized today. Nor were they recognized then. They, after all, were the “silent minority.” They were the little people, the populists — rural church pastors, long-suffering lay persons, conference evangelists.

The obvious step forward for Keysor, a trained journalist, was for a magazine. A notable voice of encouragment was from Spurgeon Dunnam of Texas Methodist (eventually becoming The United Methodist Reporter). In the September 6, 1968, issue Dunnam editorialized that the church needed a conservative voice. The liberal voice was presented by the official Methodist press with Christian Advocate and Concern (Dunnam was one who believed that an official “press” was too often public relations-oriented and thus reflected the views of the leadership) but there was no conservative voice and Good News could fill the void.

“The Texas Methodist is pleased to make known to its readers that within the past year a responsible ‘conservative’ journal of opinion has been born within the United Methodist Church. It is called simply Good News, and we think it is just that.”

Coming out of exile. Would it be possible for evangelicals to get together? On August 26, 1970, the first national convocation was held. Sixteen hundred registered and crowds on some evenings swelled to over 3,000. The speakers included luminaries such as evangelist Tom Skinner, Bishop Gerald Kennedy, Harold Ball of Campus Crusade, and E. Stanley Jones. Dr. K. Morgan Edwards of Claremont School of Theology gave the keynote address. People who came to the convocation prayed and hugged and worshipped and wept and said “Amen” and “Hallelujah” without fear of disapproving stares around them. Twenty percent of the attendees were between 20 and 35 years old. Keysor wrote of the event, “We are coming out of exile.”

The critics cried, “divisive.” Again Spurgeon Dunnam responded. In an editorial titled “Constructive Divisiveness” Dunnam commented:

“The question which remains is: are the evangelicals a divisive force within the church? Yes, they are divisive. Divisive in the same way Jesus was in first century Judaism. Divisive in the same way Martin Luther was to sixteenth century Catholicism. Divisive in the same way that John Wesley was to eighteen century Anglicanism. And, strangely enough, divisive in the same way that many liberal ‘church renewalists’ are to Methodism in our own day.

“A survey of Methodism in America today reveals these basic thrusts. One is devoted primarily to the status quo. To these, the institution called Methodism is given first priority. It must be protected at all costs from any threat of major change in direction….

“The other two forces do question the theological soundness of institutional loyalty for its own sake. The progressive, renewalist force has properly prodded the Church to take seriously the social implications of the Christian gospel…. The more conservative, evangelical force is prodding the church to take with renewed seriousness its commitment to the basic tenets of our faith…”

When Dunnam was writing those words, the Reporter was reaching a million persons per week and was the largest-circulation religious paper in the world. Under Dunnam’s leadership, it investigated both liberal and conservative activities. Even when Dunnam disagreed with Good News, he always treated us with integrity.

In the midst of all this activity, Good News was not on solid ground financially and staff-wise. Then a providential person and offer came on the scene. Dr. Dennis Kinlaw, president of Asbury College in Wilmore, Kentucky, was cheering Good News on from the sidelines, but he came up with an idea to help Good News as well as Asbury College. He offered Keysor a job of teaching journalism part-time at Asbury with the understanding that the rest of his time could be used to edit the magazine. For the fledgling Good News board it was an answer to prayer. The move was made in the summer of 1972.

At the time Good News was not even recognized as an advocacy group in the church. Engage magazine listed the special interest groups at the 1972 General Conference: Black Methodists for Church Renewal, the Women’s Caucus, the Young Adult Caucus, the Youth Caucus, the Gay Caucus. There was no evangelical caucus. By 1976 things had changed. Good News was able to generate 11,000 petitions, most having to do with maintaining the Discipline’s stand on marriage and sexuality in response to an aggressive progressive agenda.

Keysor knew that these controversial cultural and theological issues would divide the church. The institutionalists responded with the kind of language that would be used frequently of evangelicals of the Good News-type in the years to come: “reactionary,” “out-of-step,” “fundamentalist,” “highly subsidized,” “hateful,” “seeking to undermine the church’s social witness,” “not serving the interests of the church.”

One critic, Marcuis E. Taber, summed up the accusations in an article that appeared in the Christian Advocate (May 13, 1971) entitled, “An Ex-Fundamentlist Looks at the Silent Minority.” According to Tabor, Good News was an “ultrafundamentalist” movement with an emphasis on literalism and minute rules which was opposed to the spirit of Jesus. It had no future in a thinking world.

The Christian Advocate gave Keysor a chance to respond and so he did in the fall of 1971. The response, classic Keysor, was perceptive, straightforward and prophetic. It said basically that Tabor and others were reading the church situation wrongly. Storms were battering the UM Church and soon it will be forced to jettison more of its proud “liberal” superstructure. Meanwhile evangelical renewal was taking place: the charismatic movement, the Jesus People, Campus Crusade, stirrings in the church overseas. If there was a right side of history, it was with evangelical renewal. This is what it meant to be “a new church for a new world.”

Was Keysor right? Looking back on our history, this is worth a discussion.

Riley B. Case is the author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon). He is a retired United Methodist clergy person from the Indiana Annual Conference, the associate director of the Confessing Movement, and a lifetime member of the Good News Board of Directors.