by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

By Rob Renfroe –

By Rob Renfroe –

I don’t have a crystal ball. I’m not a prophet. And I’m not claiming to have “a word from God.” But I think I can see how the called General Conference may end next February.

The bishops have spoken predominantly about two options which they are likely to put forth. The first proposal is called “The One Church” Plan. Previously it was referred to as “the local option.” Each pastor would determine whether to marry gay couples and each annual conference would decide whether to ordain practicing homosexuals. We would be one church with two different sexual ethics, some of us teaching that marriage is between a man and a woman and others proclaiming that marriage is the sacred union of two persons. Some of us would teach that loving homosexual relations are a gift from God to be celebrated; others of us would refer to such relations as contrary to God’s will, even sinful.

This “one church” plan has been around for a good while. It was proposed at General Conference in 2016 and fared so poorly in committee that its rejection was a certainty and it was not even brought to the floor for a vote. This plan would require evangelicals and traditionalists to belong to a church that allows and promotes what they believe to be contrary to the clear teaching of God’s word. It’s hard to understand why the bishops think the same plan might pass when practically all of 2016’s delegates are returning to vote in 2019.

The “one church” model will be opposed in St. Louis by the same coalition that defeated it in the past – traditionalists in the U.S., delegates from Africa (almost unanimously), and most delegates from The Philippines and Eastern Europe. This coalition, or some form of it, has been the majority opinion on every significant sexual ethics vote that has come before General Conference for four decades. In fact, this alliance even defeated a less progressive proposal that United Methodists simply admit that we have differing opinions regarding homosexuality. I’m not a prophet but I don’t need to be to predict that “The One Church” Plan will fail again when it is proposed in St. Louis.

The second proposal has been referred to as “the Multi-Branch plan.” This proposal divides the church into three jurisdictions. One jurisdiction would be fully progressive with pastors required to marry gay couples. A second jurisdiction would be traditional in its beliefs and would not allow its pastor to marry same-gendered persons. A third jurisdiction would permit pastors to determine their own policies. Ordination of gay persons would likewise be required, forbidden, or allowed (but not required) of annual conferences, depending on the jurisdiction they joined.

For some evangelicals this plan is more palatable. The distance between the three branches is sufficient for some traditionalists to “live with” this model even if it’s not their first choice.

But can it pass? Probably not, because it requires constitutional amendments, meaning it must pass by a two-thirds margin at the called General Conference and by the same margin when it is considered later by annual and central conferences. Some progressives will not vote for this plan because they see it as an institutionalizing of injustice. Many evangelicals, both in the U.S and around the globe, will reject this plan because it also requires them to remain in a church that allows and promotes what the Scriptures forbid. Even if all of the progressives and one-third of the traditional delegates accept this plan, it will still fail to gain the two-thirds approval that it requires.

I’m not a prophet and I don’t have a crystal ball. But I can see a very unhappy ending for the special Conference that was called for the bishops to resolve our division over sexuality. If the only two options considered are the ones the bishops have been promoting in their press releases, chaos will be the result when they are defeated. The church will be demoralized. The bishops will have failed. Progressives will rampantly break the Book of Discipline. Conservatives will stop paying apportionments. Churches will leave the denomination. Members in huge numbers will depart to find non-Methodist churches to join. And there will be no one to look to for leadership. The bishops will have failed their trust and will have no moral authority to guide the church. The “centrist” leaders again will have lost their attempt to liberalize the church. Progressives will be seen for the true minority they are.

We will be in disarray and we will be leaderless.

In the meantime, the situation in the church is only getting worse. The decline in attendance is increasing. Bishops and annual conferences continue to disregard the Discipline by appointing self-avowed practicing homosexuals to leadership positions and by passing policies allowing the ordination of practicing LGBT persons (see page 6). More local churches are leaving the denomination. Mistrust and cynicism are growing. The morale of clergy in much of the U.S. is in the depths. Many are worried and anxious about the future of the church and its implications for their own personal situation. It is past time for the pain to end and this conflict to be resolved.

What’s our hope? That some other group will bring forth a plan that might resolve our dysfunction and our division. After all the time and expense that has been consumed in creating two plans that cannot pass, our hope is that a dissenting group of bishops, a global coalition, or some other group will create a plan that can pass. It will not be a plan that pleases everyone. It may not be a plan that “keeps us together” if that means having two or more positions regarding sexuality in one church. But it is time to resolve our differences and be done with the constant acrimony and fighting. That’s why the Conference was called. That’s what the bishops were asked to do. But if they won’t, then someone else must. Or I see a very unhappy ending for United Methodists.

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

Live nativity pageant at MCC. Photo by Caroline Chadwell, Penguin Photography International.

By Courtney Lott –

When my mom first considered the prospect of moving to Egypt, anxiety shouldered out excitement pretty fast. “Everything about your mindset changes if you want to go unnoticed,” she said. “Two Christians who had been there for awhile told me about clothing – making sure my arms were covered, pants are better, and keep your purse close to you.”

The effort to not stick out is an art for the ex-pats who live in Egypt. With a 90 percent Muslim population, it’s even harder if these ex-pats are Christians, like my parents. It is vitally important, then, to find a community of other believers.

When my parents discovered Maadi Community Church (MCC) not far from Cairo, it felt like stepping into an oasis. “The people in the church made us feel welcome immediately when they introduced new people and asked which country you came from,” my mom said. “Naturally, Dad said Texas and that got a pretty good laugh.”

With people from every tribe, tongue, and denomination in attendance, their influence spreads worldwide. Though the Muslim community shows disinterest in the church, they provide jobs for boabs (guards) and maids, and invite their children to the camps they host during the summer.

A multicultural haven, MCC strives to be an oasis for people like my parents. “[This] is an idea that has been around for a very long time,” says Rev. Steve Flora. “We’re using this whole metaphor of oasis as a place to come get refreshed. Not to stay and live and try to be safe gathered around the oasis like it’s a little fortress, but to be refreshed, recharged, refilled, and then you go out into the world.”

MCC impacts the world in a big way. From a refugee school that serves displaced people throughout Cairo, to training African pastors, to a prison ministry, the diverse congregation actively reaches out to the people in their community with the love of Jesus.

Through God’s goodness, MCC has outgrown the property they share with St. John’s Episcopal Church. Sharing a property with over eleven other churches limits their time and as well as their resources. Moreover, there is a unique, if small, window of opportunity for the church to gain coveted official governmental permission to find their own place of worship.

Since the time President Gamal Abdel Nasser created the modern state of Egypt in the mid-1950’s, the government has refused to grant new church licenses. Now, however, the government has begun granting new licenses for reasons unknown. Because of this, MCC is now seeking to raise funds to buy a building in Maadi.

“[A new building] offers, not only for us, but for other people, other churches, other organizations, another place that they can come and have church on a legally sanctioned church property,” says Flora. “For me and our family it’s an investment in the future, not my future so much, as the future of Egypt and the church.”

Please pray for Maadi Community Church as they seek their own property and continue to work to be the hands, feet, and mouthpiece of the Lord in a community that is not open to Jesus Christ. For more information on the work God is doing there, visit http://maadichurch.com.

Courtney Lott is editorial assistant at Good News.

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

By Steve Beard –

By Steve Beard –

The holy-rolling and guitar-swinging hymn singer who arguably gave birth to rock and roll and was buried in an unmarked grave for more than 35 years is finally getting the respect she deserves. For the fans of Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915-1973), the posthumous adulation is bittersweet.

Ignored and neglected for decades, she was finally inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame on April 14. “She is the founding mother who gave rock’s founding fathers the idea,” the Hall of Fame acknowledged. Sister Rosetta’s obscurity is both regrettable and pitiable. Her music and talents were gender-eclipsing, genre-defying, and ground-breaking. She was a finger-picking, gospel-rocking trailblazer on the guitar long before Jimi Hendrix, Chuck Berry, or Eric Clapton.

“Sister Rosetta Tharpe holds an important role in the evolution of American music; a great innovator, she not only unapologetically bridged the seemingly enormous chasm between secular and church music, she also helped pioneer the unique sound of rock and roll guitar,” Rhiannon Giddens, lead singer of the Grammy Award-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops, has observed. “Her infectious spirit, impeccable musicality, and sheer joy in her faith are obvious in every recording and are a source of great inspiration.”

Tharpe grew up in a conservative church setting that was simultaneously progressive about women in ministry, loud musical instruments, and an expressive worship style that encouraged hand clapping and dancing. In some quarters, this lively expression was looked down upon and dismissed as undignified holy rollin’, but this was the high-octane incubator for Rosetta that gave her permission and a platform to express her gifts as a young woman.

Tharpe’s mother was a mandolin player and a traveling evangelist with the Church of God in Christ, the African-American Pentecostal-Holiness denomination founded in 1897. Accompanying her mother, Rosetta began playing “Jesus on the Mainline” on the guitar at age four. After years of playing in revival meetings and church services, Rosetta moved to New York City in 1938 and became the first gospel artist to be signed to Decca Records. She performed with Cab Calloway at Harlem’s segregated Cotton Club and was featured at John Hammond’s “From Spirituals to Swing” sold-out event at Carnegie Hall.

“She sang some gospel songs that brought the house down,” Count Baise recalled. “She sang down-home church numbers and had those old cool New Yorkers almost shouting in the aisles. There were lots of people out there who had never heard that kind of singing, but she went over big.”

Sister Rosetta’s star was on the rise. She was, after all, the first solo gospel artist to play at the famous Apollo Theater in Harlem. While the white audiences were thrilled to hear African American gospel music for the first time, many of her church supporters were aghast that she was taking what was known as “sanctified” music into nightclubs. Walking the tightrope between the tabernacle and the spotlight – and making a living as a musician – would prove to be both a burden and challenge for her entire life.

Sister Rosetta was famous for her raucous and rollicking music and mega-watt smile. But it was her guitar work that mesmerized audiences – saints, sinners, black, white, men and women. “Rapidly finger-picked notes press up against full-on power chords that linger languidly in the air,” Dr. Gayle Wald writes in her Tharpe biography Shout, Sister, Shout. “She squeezes notes from the high end of the pitch, relishing the gentle fuzz of distortion, then cajoles the instrument, commanding, ‘Let’s do that again.’”

In 1942, Billboard magazine called her music “rock-and-roll spiritual singing” – a decade before the phrase was commonplace. Tharpe attempted to “inhabit an in-between place where the worlds of religious and popular music intersected and overlapped,” Wald writes. “Even when limiting herself to a church repertoire, she stuck out as a loud woman: loud in her playing, loud in her personality. In concert, she combined the spontaneous fervor of religious revivals with the practiced production values of Broadway variety shows.”

The revolutionary nature of what she was doing didn’t go unnoticed by up-and-coming superstars. “Sister Rosetta Tharpe was anything but ordinary and plain,” said Bob Dylan. “She was a powerful force of nature.” She influenced Tina Turner, Aretha Franklin, and Karen Carpenter. “Say, man, there’s a woman who can sing some rock and roll,” Jerry Lee Lewis once said. “I mean, she’s singing religious music, but she is singing rock and roll. She’s … shakin’ man … She jumps it.” She was also Johnny Cash’s favorite artist.

“Elvis loved Rosetta Tharpe,” proclaimed Gordon Stoker of The Jordanaires, the back up vocal quartet for Presley. “Not only did he dig her guitar playing but he dug her singing too.” Before backing Elvis, The Jordanaires toured with Tharpe – flipping the cultural picture inside out as a white quartet sang back up for an African American performer.

In a belligerently segregated era, she was a striking figure with high heels and ornate sequined dresses accessorized by a Gibson SG guitar strapped over her shoulder. “As a black woman with few outlets for public speaking, Rosetta fashioned a distinct means to speak through her guitar,” Wald writes. “As a woman who could outplay her male counterparts, she managed the ‘threat’ of her virtuosity to men by undercutting it with disarming humor and a dose of feminine decorum.” Thankfully, modern day fans can watch a handful of grainy YouTube videos, including scenes where she was guest host of TV Gospel Time on NBC.

Tharpe’s recording of “Strange Things Happening Every Day” with boogie-woogie pianist Sammy Price in 1944 was the first gospel song to make Billboard’s “race records” Top Ten. A smart case has been made that it might be the first rock and roll record. That’s why her fans find sweet comfort in the Hall of Fame nod. “All this new stuff they call rock ’n’ roll, why, I’ve been playing that for years now,” Sister Rosetta told London’s Daily Mirror back in the 1950s. “Ninety percent of rock-and-roll artists came out of the church, their foundation is the church.”

The historic relationship between the church and rock has fluctuated between resentment to hostility – sometimes justifiably. Rosetta fought hard to stay in the good graces of the church that nurtured her. That didn’t always work out but she would be the first to remind the church that there must be some way for the amped-up joyful noise of ecstatic worship to be shared with those who will never enter a sanctuary. To those who would tell her “come out from among them and be ye separate” (2 Corinthians 6:17), she might respond, “let your light shine before men, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:15-16).

During one spat with detractors, she responded: “God has said, ‘If I am for you, I am more than the world against you.’ He has also said, ‘Hold your peace, I will fight your battles,’ and that is what I am going to do and carry on for the Lord.”

Sister Rosetta suffered a stroke in 1970 and died three years later at the age of 58. Her widespread popularity had waned in comparison to previous decades. Her funeral was far more modest than her larger-than-life personality. Sadly, she was buried in an unmarked grave. As word of this travesty was discovered by fans more than 30 years later, money was raised for a proper tombstone. “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy,” it now properly states. “She helped to keep the church alive and the saints rejoicing.”

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | May/June 2018

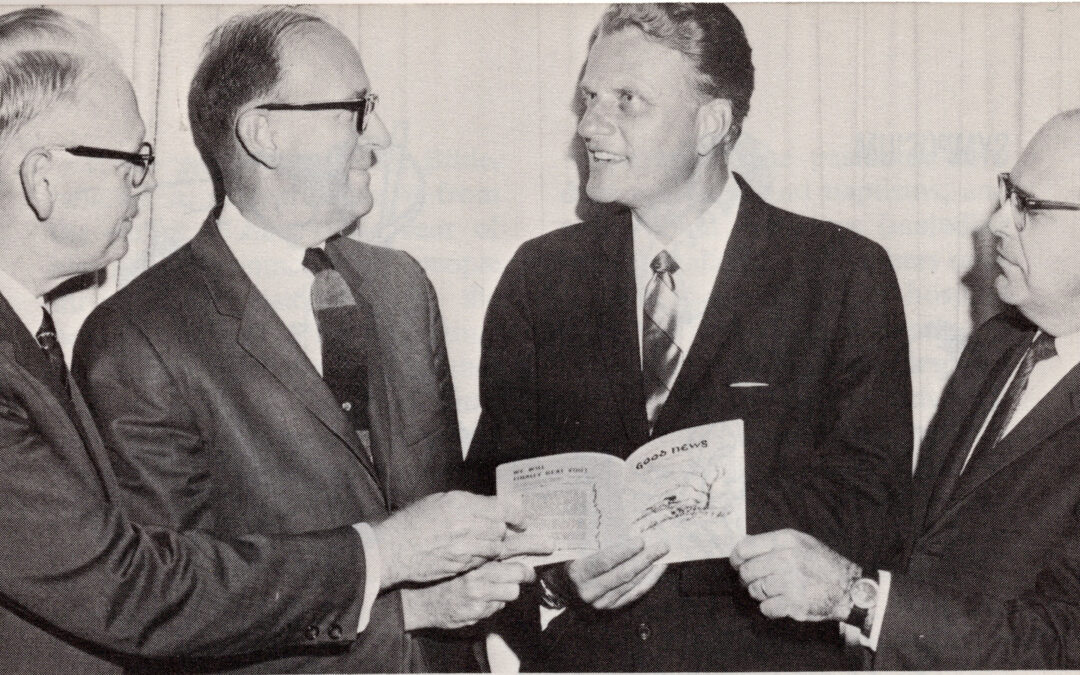

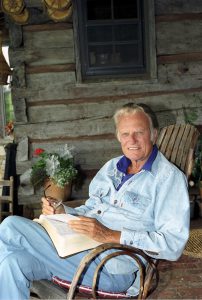

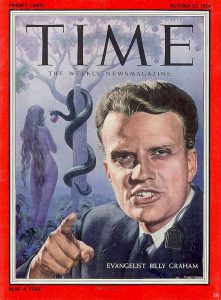

Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Into the Arms of Eternity: Remembering Billy Graham

By Steve Beard –

Wherever he landed around the globe, Billy Graham spent his life preaching a simple and sincere message of God’s love for all people, the urgent need for conversion, and the assurance that Jesus Christ walks with believers in the brightest and darkest of times. Throughout his illustrious ministry, Graham preached to nearly 215 million people in more than 185 countries and territories via his simulcasts and rallies. His audience exposure leaps exponentially when television, newspaper columns, videos, magazine stories, webcasts, and best-selling books are factored in.

Illustrative of his technological wizardry, Graham once spearheaded an event more than two decades ago that astonishingly utilized 30 satellites broadcasting taped evangelistic messages from Graham in 116 languages to 185 countries.

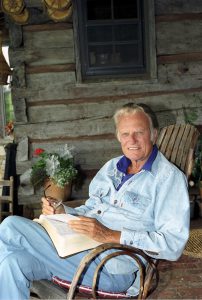

The news of his death on February 21 at his home in Montreat, North Carolina, at the age of 99, was observed with both joy and sorrow. The lanky world-renowned evangelist was buried in a rudimentary pine plywood coffin made by men convicted of murder from the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

For Christians, Graham was a role model in holding firm to both evangelism and integrated social action, orthodoxy and generous ecumenism, grace and truth, love and repentance. In addition to preaching his life-transforming message, he was pivotal in helping form numerous evangelical institutions that will be remembered as part of his fruitful legacy.

“Billy Graham was a man with beautiful integrity, clothed with humility, and combined with a sterling message of the gospel,” Dr. Robert Coleman, author of The Master Plan of Evangelism, told Good News. Coleman was a close friend and associate of Graham for 60 years, leading the Institute of Evangelism in the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College and serving as Dean of the Billy Graham International Schools of Evangelism. Coleman was one of a handful of United Methodists who attended Graham’s funeral along with Drs. Eddie Fox, Maxie Dunnam, and Timothy Tennent.

“Wherever we traveled around the world, Billy was a master of making a nobody feel like a somebody,” Coleman recalled. “You always felt lifted up in his presence. Whether you were a street sweeper or a king, Billy saw you as someone deeply loved and treasured by God.”

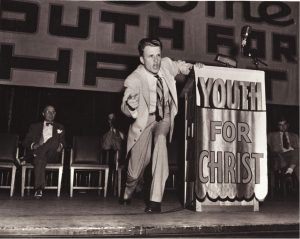

Although most well known as a Baptist, Graham had a special relationship with Methodists dating back to his early friendship with lay evangelist Harry Denman, a man Graham described as “one of the great mentors for evangelism in my own life and ministry – and for countless others in evangelism as well.” Denman, who died in 1976, was the leader of the Commission on Evangelism of the Methodist Church. In the forward to the book Prophetic Evangelist, Graham wrote: “I never knew a man who encouraged more people in the field of evangelism than Harry Denman.”

Methodist Bishop Gerald Kennedy’s position as chairman of the Billy Graham rally in Los Angeles in 1963 caused a controversial stir among fundamentalists and others who did not see a place for mainline denominations in Graham’s evangelistic efforts. In the premier issue of Good News in 1967, Kennedy wrote that he had hoped his position would be an opportunity to bring conservative evangelicals and mainline churches closer together. “We never succeeded at eliminating all our differences,” he wrote, “but we did make progress in talking to one another and trying to listen to each other with some appreciation.”

Over the decades, United Methodists were inspired by Graham’s message, temperament, and integrity. “No voice in the past half-century has been more powerful and faithful in pointing clearly to Jesus Christ than the message of Billy Graham,” Dr. Eddie Fox, former World Director of World Methodist Evangelism, said. “His message always led persons to Jesus Christ.” Fox was a speaker at several of the Billy Graham Schools of Evangelism.

According to United Methodist News Service, the late Bishop Leontine Kelly, who headed the evangelism unit of the denomination’s Board of Discipleship before her election to the episcopacy in 1984, characterized Graham’s preaching as “electric.” “His purposes were clear and his commitment to Jesus Christ was unwavering,” said Kelly, who died in 2012. “We will always be grateful for television, which enabled his communication of the gospel of Jesus Christ to millions.”

Graham had unparalleled reach. A 2005 Gallup poll revealed that 16 percent of Americans had heard Graham in person, 52 percent had heard him on radio, and 85 percent had seen him on television.

“Only the large expressive hands seem suited to a titan,” biographer William Martin, author of A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story, observed. “But crowning this spindly frame is that most distinctive of heads, with the profile for which God created granite, the perpetual glowing tan, the flowing hair, the towering forehead, the square jaw, the eagle’s brow and eyes, and the warm smile that has melted hearts, tamed opposition, and subdued skeptics on six continents.”

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

In hindsight, Graham registered his regret for not participating in civil rights demonstrations. “I think I made a mistake when I didn’t go to Selma, [Alabama in 1965],” Graham confessed to the Associated Press in 2005. “I would like to have done more.” It has been properly noted that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. considered Graham an ally. “Had it not been for the ministry of my good friend Dr. Billy Graham, my work in the Civil Rights Movement would not have been as successful as it has been,” said King. Other African American leaders, however, regret that Graham was not more front-and-center in the struggle.

“Graham clearly felt an obligation to speak against segregation, but he also believed his first duty was to appeal to as many people as possible. Sometimes he found these two convictions difficult to reconcile,” Martin wrote in A Prophet with Honor.

Close proximity to the corridors of political power – especially the Nixon White House – occasionally blindsided Graham. When asked in 2011 by Christianity Today, a magazine he helped launch, if there was anything he would have done differently, Graham responded: “I would have steered clear of politics. I’m grateful for the opportunities God gave me to minister to people in high places; people in power have spiritual and personal needs like everyone else, and often they have no one to talk to. But looking back I know I sometimes crossed the line, and I wouldn’t do that now.”

Of his regrets, those closest to home were the most sensitive. “Ruth says those of us who were off traveling missed the best part of our lives – enjoying the children as they grew. She is probably right. I was too busy preaching all over the world.” Ruth Bell married Graham in 1945 and the couple had five children. “I came through those years much the poorer psychologically and emotionally,” he reflected. “I missed so much by not being home to see the children grow and develop.”

Graham questioned some of the aspects of his jet-setting ministry. “Sometimes we flitted from one part of the country to another, even from one continent to another, in the course of only a few days,” he recalled. “Were all those engagements necessary? Was I as discerning as I might have been about which ones to take and which to turn down? I doubt it. Every day I was absent from my family is gone forever.”

Johnny Cash and Billy Graham. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Although Graham never had regrets about committing his life to preaching a Christian message, he wished he would have spent more time in nurturing his own personal spiritual life. “I would spend more time in prayer, not just for myself but for others,” he said. “I would spend more time studying the Bible and meditating on its truth, not only for sermon preparation but to apply its message to my life. It is far too easy for someone in my position to read the Bible only with an eye on a future sermon, overlooking the message God has for me through its pages.”

Boxing champion Muhammad Ali meets with Ruth and Billy Graham at their North Carolina home. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

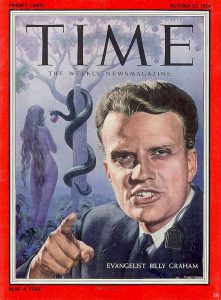

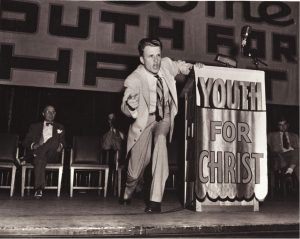

“He brought down the storm.” Three years ago, Bob Dylan called Graham the “greatest preacher and evangelist of my time — that guy could save souls and did.” The music icon testified in AARP The Magazine to having attended some Graham rallies in the 1950s and ‘60s and described them in a distinctly Dylanesque way: “This guy was like rock ’n’ roll personified – volatile, explosive. He had the hair, the tone, the elocution – when he spoke, he brought the storm down. Clouds parted. Souls got saved … If you ever went to a Billy Graham rally back then, you were changed forever. There’s never been a preacher like him. … I saw Billy Graham in the flesh and heard him loud and clear.”

U2 lead singer Bono wrote a poem for the Grahams. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Although he is most well-known for his relationships with politicians, straight-and-narrow Graham was best of friends with Johnny Cash, the blue-collar troubadour who, when they met in 1969, was making headlines for recording live albums in Folsom State and San Quentin prisons. The Grahams and Cashs grew to be very close. Not only did Johnny and June Cash perform at Graham rallies, but Billy and Ruth joined the Cash family on numerous vacation outings.

“I’ve always been able to share my secrets and problems with Billy, and I’ve benefited greatly from his support and advice,” Cash wrote in his autobiography. “Even during my worst times, when I’ve fallen back into using pills of one sort or another, he’s maintained his friendship with me and given me his ear and advice, always based solidly on the Bible. He’s never pressed me when I’ve been in trouble; he’s waited for me to reveal myself, and then he’s helped me as much as he can.”

Despite what some perceived as a squeaky-clean piety that gravitated to the halls of power, Graham had a deep and abiding love for the outsiders and the spiritual searchers. “It was eleven o’clock on a Sunday morning, but I was most definitely not in church,” Graham wrote in his autobiography Just As I Am. “Instead, to the horror of some, I was attending the 1969 Miami Rock Music Festival.” Preaching from the same concert stage as Canned Heat, the Grateful Dead, and Santana, Graham wrote about his delight to speak to “young people who probably would have felt uncomfortable in the average church, and yet whose searching questions about life and sharp protests against society’s values echoed from almost every song.”

Graham actually donned a disguise to get a feel for the festival the night before he would preach. “My heart went out to them,” he wrote. “Though I was thankful for their youthful exuberance, I was burdened by their spiritual searching and emptiness.”

Although Graham was prepared to be “shouted down,” he was “greeted with scattered applause. Most listened politely as I spoke.” He told them that he had been listening carefully to their music: “We reject your materialism, it seemed to proclaim, and we want something of the soul.” Graham proclaimed that “Jesus was a nonconformist” and the he could “fill their souls and give them meaning and purpose in life.” As they waited for the upcoming bands, Graham’s message was, “Tune in to God today, and let Him give you faith. Turn on to His power.”

Graham’s well-known message also did not hinder his ability to reach beyond evangelical boundaries. He longed for improved relationships between Roman Catholics and Protestants and was a trusted friend of Catholic television pioneer Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. “We are brothers,” Pope John Paul II told Graham during a visit to the Vatican.

In 1979, the late Muhammad Ali, three-time world heavyweight boxing champion, spent several hours with Graham in the evangelist’s home in North Carolina. “When I arrived at the airport, Mr. Graham himself was waiting for me. I expected to be chauffeured in a Rolls Royce or at least a Mercedes, but we got in his Oldsmobile and he drove it himself,” Ali recalled. “I couldn’t believe he came to the airport driving his own car. When we approached his home I thought he would live on a thousand acre farm and we drove up to his house made of logs. No mansion with crystal chandeliers and gold carpets, it was the kind of house a man of God would live in. I look up to him.”

Ali told the press, “I’ve always admired Mr. Graham, I’m a Muslim and he’s a Christian, but there is so much truth in the message he gives, Americanism, repentance, things about government and country – and truth. I always said if I was a Christian, I’d want to be a Christian like him.”

Generations later, Graham’s magnetism never weakened. One month after the Irish band U2 played an unforgettably emotional halftime show at the Super Bowl in 2002 memorializing the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Bono responded to an invitation to visit the Grahams at their home. Inside a collection of the work of Irish poet Seamus Heaney given to Ruth and Billy, Bono had written a poem that refers to “the voice of a preacher/loudly soft on my tears” which was the “lyric voice that gave my life/A Rhyme/a meaning that wasn’t there before.” The poem is on display at the Billy Graham Library in North Carolina.

In a touching tribute to Graham three years later, Bono said: “At a time when religion seems so often to get in the way of God’s work with its shopping mall sales pitch and its bumper sticker reductionism, I give thanks just for the sanity of Billy Graham – for that clear empathetic voice of his in that southern accent, part poet, part preacher – a singer of the human spirit, I’d say. Ah, yeah I give thanks for Billy Graham.”

Billy Graham preaches in the 1950s. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Evangelistic energy. In addition to calling men, women, and children – rich and poor, black and white, powerful and humble – all over the globe to a commitment to Christ, Graham was also reminding the institutional church of the foundational need to share the faith. In 1976, his efforts were recognized by the United Methodist Association of Evangelists as one of the earliest recipients of the Philip Award. Four years later, he preached at the denomination’s Congress on Evangelism on the campus of Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“Many have moved from a belief in man’s personal responsibility before God to an entirely new concept that assumes all men and women are already saved,” said Graham in 1980. “There’s a spreading universalism, which has deadened our urgency that was had by John and Charles Wesley, Francis Asbury, E. Stanley Jones, and others like them.

“This new evangelism leads many to reject the idea of conversion in its historical Biblical meaning and the meaning historically held and preached and taught by the Methodist Church.”

Graham concluded his remarks by quoting Methodist leader John Wesley in 1784: “You have nothing to do but to save souls, therefore spend and be spent in this work.” He continued to quote Wesley, “It is not your business to preach so many times and to take care of this or that society; but to save as many souls as you can; to bring as many sinners as you possibly can to repentance and with all your power to build them up in that holiness, without which they will never see the Lord.”

Graham reminded the participants of their heritage. “Let it be remembered that the Methodist church began in the white peak of conversion and intense evangelistic energy,” he said. “Let it be recalled that the Methodist church is an evangelistic movement.”

Good News connection. More than a decade before his address at the Congress on Evangelism, Graham’s preaching played a key role in the conversion of Good News’ founding editor Charles Keysor. The evangelist’s encouragement was also an important inspiration during the ministry’s formative years.

“I have always believed that The United Methodist Church offers tremendous potential as a starting place for a great revival of Biblical Christian faith,” Graham wrote in a personal note of encouragement to the staff and board of directors on the occasion of the 10-year anniversary of Good News. “Around the world, millions of people do not know Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord, and I believe that The United Methodist Church, with its great size and its honorable evangelistic tradition, can be mightily used by God for reaching these lost millions,” wrote Graham in 1977.

“I have been acquainted with the Good News movement and some of its leaders since 1967. To me it represents one of the encouraging signs for the church fulfilling its evangelistic mission, under the Bible’s authority and the leadership of the Holy Spirit. At the forefront of the Good News movement has been Good News magazine. For 10 years it has spoken clearly and prophetically for Scriptural Christianity and renewal in the church. It should be read by every United Methodist.”

Everyone associated with Good News in that era – and subsequent generations – found great inspiration in Graham’s words.

The message and the man. “Billy Graham’s ministry taught me to step out in faith and trust God in all things in my life,” Dr. Timothy C. Tennent, president of Asbury Theological Seminary, said in a statement after attending Graham’s funeral in North Carolina.

“After preaching in Red Square in what was then the Soviet Union, Billy Graham stopped at Gordon Conwell, where I was a student. Someone asked Mr. Graham if he had been used as part of Soviet propaganda. He replied that he had preached the same Gospel in Red Square as he did around the world. This taught me not to worry about the discouraging naysayers and critics in my ministry. Even Billy Graham’s funeral continued to teach us about the grace and glory of God.”

There was one testimony of poignant grace at Graham’s funeral that caught the attention of the Rev. Dr. Maxie Dunnam, former World Editor of The Upper Room and evangelical United Methodist leader. “The most meaningful for me was the sharing of one daughter who had a painful marriage that ended in divorce,” he recalled. “She spoke about her shame and how dreadful it was to think of how this was affecting her Mom and Dad, but how redemptive it was when she was welcomed home by Billy with open arms.”

“It was a powerful prodigal daughter story. There was no pretension of perfection,” Dunnam said. “The feeling was that we were at a large family funeral, friends gathered to remember, to share their grief and celebrate the life of a loved one. Again, the emphasis was not on the man but the message.”

When speaking about the end of his own life, Graham used to like to paraphrase the words of one of his heroes, D. L. Moody, an evangelist of a different era: “Someday you will read or hear that Billy Graham is dead. Don’t you believe a word of it. I shall be more alive than I am now. I will just have changed my address. I will have gone into the presence of God.”

Graham’s admirers note the change of address with deep respect and love.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Opening photo: Billy Graham discusses the second issue of Good News with (left to right) Dr. Frank Stanger, president of Asbury Theological Seminary; the Rev. Philip Worth, United Methodist pastor and chairman of the Good News board of directors; and Dr. Charles Keysor, founder of Good News.

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

Delegates study legislation at the 2012 United Methodist General Conference in Tampa, Florida. A UMNS photo by Mike DuBose.

By Scott Kisker –

With the 2019 called General Conference looming, it is time to address the risks posed to our United Methodist polity as a peculiar articulation and preserver of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church.

The United Methodist Church is set up as a conciliar catholic church – the only one I know of. This means that, in our polity, the highest earthly authority is not bishops. While the bishops gather in what they call a council, that council is not our highest authority. Rather, the highest authority in The United Methodist Church is a particular regular lay and clergy council, which we call General Conference.

This General Conference is catholic (I use “catholic” here in the sense of representing the whole of The United Methodist Church). General Conference includes proportional participation from global United Methodism. This catholic council has allowed United Methodism to avoid captivity to peculiar cultural contexts better than most mainline Protestants — resisting some of the pressure to capitulate to culture and turn the worship of Yahweh, the Creator, into that of a tribal deity.

Our catholic council, General Conference, is the instrument of unity in our polity. It is instituted to preserve unity of teaching and practice among the people called Methodists. It is where we decide “what to teach, how to teach and what to do.” This is not a faux unity that in practice allows people to conform what they believe and how they behave to the forces within their particular time, place, and ethnicity. And every culture and era has its principalities and powers.

We hear a lot about contextuality, as though it were an unquestionable good. This rhetoric tickles contemporary ears, but it has a mixed track record in history. There are legions of examples in the modern era alone where churches have accommodated to the evils of their times and cultures, deforming the gospel. “Contextualization” of the Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church allowed for slave holding in the American South beginning in 1808, as well as the acceptance of racist segregation in the name of “unity” for the formation of The Methodist Church in 1939.

Resistance to the pressures of time and context is hard. But resistance is essential if a 2,000-year-old revelation of the Word in flesh is to be passed on to our children for their salvation. The good news is that our instrument of unity, a catholic, global General Conference, disciplines us to contend with one another cross-culturally for the truth of the One God, and to preserve the faith “believed at all times, in all places, by all peoples,” as Vincent of Lerins wrote.

Bishops in our polity hold an itinerant office. They are responsible for Word, sacrament, and order in the church as elders, but not as a separate order from other elders. Their office is an extension of, and attached to, the office of elder. They are not Lords of the Church or princes of a diocese. They cannot speak for the church, even ex cathedra. Their authority comes from the General Conference to do a particular job. They are sent forth as officers to hold members and congregations and annual conferences accountable to the doctrine and discipline established by our catholic council, the General Conference. In their apostolicity, their duly sent-ness, (apostello means “to send”), they visibly connect Methodists across space and culture to the General Conference, not to themselves.

Through an extraordinary procedural move at our 2016 General Conference, a group of bishops, aided by some influential pastors, managed to prevent the will of General Conference for corporate discipline from being articulated. By an appeal to “unity,” they were able to get a plan passed to transfer the power to mediate conflict in our church from our instrument of unity (the General Conference) to themselves, a less catholic, less accountable (thanks to jurisdictional divisions) group with no intrinsic authority to resolve such issues.

Given what the bishops have indicated, they are likely to propose in 2019, the temporary authority they managed to acquire in 2016 seems to have encouraged more presumption of authority. Anything like what could have passed General Conference in 2016 (the avoidance of which was the reason for their maneuvers) looks unlikely to come from the council of bishops. That alone should give the church pause. Should General Conference accept any proposal from the bishops other than, perhaps, a proposal that bishops uphold their vows to enforce the doctrine and discipline discerned through general conferencing, the General Conference will have demoted themselves and elevated the council of bishops to a position in our polity it was never intended to have.

Though many bishops do not realize it, if they are successful in pushing through either of the plans they have said they are seriously considering, they will undermine the conciliar and catholic nature of our church, thereby unraveling the very logic of Methodist ecclesiology. The catholic council for United Methodists, General Conference, will be impotent for anything that matters. “What to teach, how to teach, and what to do” will become a regional, local, even individual concern.

The irony is that this is all being done in the name of “unity.” In practice we will have divided the church into congregations or regions or ideologies, while crying “unity, unity,” where there is no unity. Definitive for being “United Methodist” will be where you live and who is your bishop. That is not unity. That will only accelerate the forces of tribalism and atomization. Our connection will, at most, be to our bishops, who, despite the rise of their council’s status, will de facto be subject to the whims of culturally captive conferences or congregations.

We will not be a catholic church. The global nature of our discernment of the Spirit will, for practical purposes, be at an end. We will not be a conciliar church. Our council, the General Conference, will be a pageant. General Conference will no longer be where we do the difficult work of cross-culture discernment, will no longer have authority for the global church, and will no longer bind us together. We will have rendered useless the instrument of United Methodist unity.

Should the bishops succeed, there will be little of historic Methodism left in a reconfigured United Methodist Church. The council of bishops will have made unrecognizable the historic Methodist understanding of the unity of the church, the catholicity of the church, the apostolicity of the church (and their own apostolic office), not to mention the sanctity of the church and 4,000 years of sexual ethics by communities who worship the one creator God.

Our name will be rhetoric with no content. We will be neither United nor Methodist. More crucial though, we will have surrendered our claim to be “Church.” All Nicene marks (one, holy, catholic and apostolic), as historically interpreted by Methodists, will have been obliterated in a new United Methodism.

Scott Kisker is Professor of Church History and Associate Dean  of Masters Programs at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of Mainline or Methodist? Recovering Our Evangelistic Mission (Discipleship Resources) and is one of the contributors featured in Holy Contridictions: What’s Next for the People Called United Methodists (Abingdon).

of Masters Programs at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of Mainline or Methodist? Recovering Our Evangelistic Mission (Discipleship Resources) and is one of the contributors featured in Holy Contridictions: What’s Next for the People Called United Methodists (Abingdon).

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

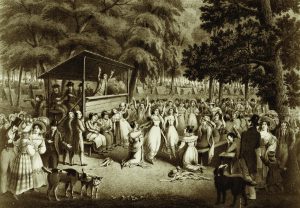

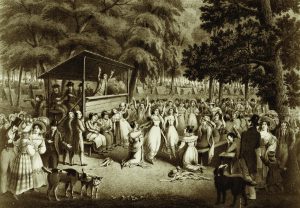

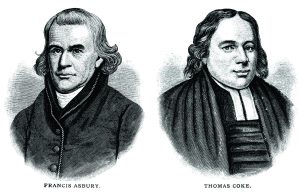

Camp meetings and other types of religious services were conducted regularly by Methodists. (Lithograph of 1829 camp meeting, Library of Congress).

By William Payne –

As The United Methodist Church prepares to meet in St. Louis next year for the special-called General Conference to decide its future, now is a good time to take a sober assessment of the state of our current denomination.

• Over the last forty-eight years, it has lost over four million members. The numerical decrease equals the combined memberships of the United Church of Christ, the Episcopal Church, and the Presbyterian Church USA.

• American Methodism has declined from 6.5 percent to 2.15 percent of the American population.

• Today, one-third of the UMC’s membership is over sixty-five. Another 30 percent is between 50 and 64. Only 9 percent is under thirty.

• The Western Jurisdiction membership has plunged by 10 percent since 2013.

Sociology of religion theories explain that when churches try to lower the barrier between biblical faith and secular practices by embracing secular values, traditional members become alienated and secular people aren’t evangelized. Moreover, spiritually hungry people who could be evangelized are more likely to go to traditional churches. In short, contextualizing Christianity to accommodate secularism is not a proven approach for reaching unchurched secular people. To put it bluntly, large percentages of people are still going to church. However, the UM share of the pie has grown exceedingly small.

The marriage and sexuality debate illustrates this issue. Every U.S. denomination that has embraced gay marriage and the ordination of gay clergy has experienced drastic numerical declines. Most of those denominations rightly anticipated that traditional members would flee to other churches. However, they wrongly believed that large numbers of unchurched gay and gay-friendly people would fill the void by joining their churches. The common notion that LGBT people will become practicing Christians if the church endorses homosexuality hasn’t proven true. In reality, churches that hope to win the secular masses must challenge secular identity by presenting an alternative identity, one that appeals to some unrealized felt need and feeds a spiritual hunger that can only be satisfied through a transformational relationship with Jesus.

Fortunately, American Methodist history offers a point of reference from which the current malaise can be analyzed. Early American Methodism was evangelistically potent and fully counter-cultural. From its founding to the mid-1800s, it experienced exponential growth. In 1812, it became the largest denomination in America. This is the great miracle of Methodism. In a mere twenty-seven years from its founding in 1784, Methodism fully upended the established churches with its message of holiness, exuberant worship, and experiential faith.

The relentless emphasis on holiness and spiritual growth necessitated a corresponding stress on keeping the discipline. For example, Methodist preachers didn’t give altar calls to invite people to join the church. Instead, they pleaded with the people to flee from the wrath to come. When a hearer felt deep conviction, the awakened person would be invited to join a Methodist class. Through participation in the class, the seeker would experience guided spiritual growth. After six months to a year, the new class member could be given a class ticket and be enrolled in the society. Only those who were enrolled in society were counted as members.

Because of the need to keep the discipline, the circuit riders tested the members on a regular basis. Those who didn’t follow the rules were purged from the society or returned to probationary membership. Wesley defended the need for purging members who didn’t evidence growth in grace because half-hearted members destroyed the spiritual vitality of the church and hindered others from going forward in grace.

Early American Methodism was so intent on maintaining its stringent membership standards that the relationship of members to participants was 1:12. One arrives at that number from the correspondence of the bishops. In 1791, Bishop Coke bragged that the adults which made up the Methodist congregations equaled 750,000. If Coke would have included children, the number would have swelled to over one million! In that year, the membership was 61,082. In 1797, Bishop Asbury said that one million people were their regular hearers. No one knew Methodism better than Asbury.

Based on the bishops’ estimations, approximately 18.5 percent of the US population participated in Methodism during the 1790s even though the membership only equaled about 1.5 percent of the US population.

Furthermore, if one counted participants instead of members, American Methodism would have become the largest church in America a mere decade after it was founded! As appealing as that might have been, the bishops knew that they could not lower the membership standards to allow attendees to join until they accepted the discipline. Yes, in early America, being a Methodist meant that a person was a disciple of Jesus Christ.

Today, from their exalted places in heaven, Bishops Coke and Asbury are pleading with the current bishops to keep to the discipline. Will the UM bishops remember our heritage and the reason why God raised up the people called Methodist? Placating the progressive wing won’t grow the church, gain social influence, stave off massive membership decline, evangelize the secular masses, or advance the reign of God.

In addition to its disciple-making apparatus, early American Methodism grew because stalwart circuit riders bravely endured great privation to preach the gospel to the burgeoning population. Circuit riders didn’t live in parsonages or drive comfortable cars when they did their work. They didn’t even preach in many church buildings. Rather, they traveled the country by horse. Since they didn’t earn enough money to sleep in taverns, they had to get lodging wherever they could find it.

The total dedication of the circuit riders to the evangelistic mission entailed extreme poverty. Since they lived on the road and only earned $64 a year, marriage was not an option. Plus, many didn’t receive their full salary. All of this led to malnutrition, disease, and premature death. Most died at a young age. This gives new meaning to why the assembled preachers began every conference by singing the Wesleyan hymn, “And Are We Yet Alive?”

History shows that God worked through the sacrificial efforts of the small army of Methodist preachers. They covered America in a loose web of circuits and corresponding preaching points. In time, that network led to the founding of an evangelical church in every city, hamlet, and outpost in America. Rapid membership growth and social transformation followed. In short, early American Methodists didn’t accommodate the culture. They changed it!

Yes, God raised up American Methodism to evangelize the land and spread the message of holiness. In fact, the work of early Methodists was so successful that it did more to shape the Christian ethos of the emerging American Republic than any other social force. Furthermore, the spiritual foundation that it helped to lay is a primary reason why America has not gone the way of Western Europe and Canada.

As United Methodists look forward to the specially called General Conference, the delegates must consider the unfinished business of the last General Conference. Before the UM Church can look forward and see with clarity where God wants it to go, it should look backward and rediscover why God raised up this church. A denomination that separates itself from its heritage and its ethos will never find spiritual vitality, social influence, or numerical success.

The future of American Methodism is in the balance. Thankfully, a new report from Harvard University gives cause for great optimism. “Recent research argues that the United States is secularizing, that this religious change is consistent with the secularization thesis, and that American religion is not exceptional,” reports sociologists Sean Bock and Landon Schnabel in Sociological Science. “But we show that rather than religion fading into irrelevance as the secularization thesis would suggest, intense religion—strong affiliation, very frequent practice, literalism, and evangelicalism—is persistent and, in fact, only moderate [secular] religion is on the decline in the United States…. The intensity of American religion is actually becoming more exceptional over time.”

In truth, God has left an open door in the American landscape. Secular and moderate religion won’t succeed. Evangelical churches have an opening to discover a secular field that is ripe unto harvest. Will United Methodism remain true to its heritage and mobilize an army of dedicated preachers to evangelize the secular masses? If the UM Church doesn’t go through the open door and reap the ripening harvest, God will give American Methodism’s torch to another church. The choice is ours.

William P. Payne is the Harlan and Wilma Hollewell Professor of Evangelism and World Missions at Ashland Theological Seminary. He is an ordained United Methodist elder in the Florida Annual Conference and the author of American Methodism: Past and Future Growth (Emeth, 2013) and Adventures in Spiritual Warfare (Wipf and Stock, 2018).