Archive: Shaping our Theological Core

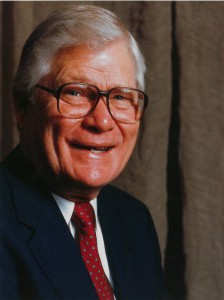

It was the fiery speech about seminary education given by Dr. Ed Robb Jr., an outspoken evangelist from Texas, that caught the attention and ire of Dr. Albert Outler, preeminent Wesleyan scholar at Perkins School of Theology. Through the eventual friendship of these two unique and legendary figures within United Methodism, nearly 150 Wesleyan scholars committed to the historic faith have since earned PhDs or ThDs through A Foundation for Theological Education (AFTE).

The foundation affirms the divine inspiration and ultimate authority of the Scriptures in matters of faith and practice; incarnation of Jesus Christ as fully God and fully human; necessity of conversion as a result of repentance from sin and faith in the Lord Jesus Christ; the church is of God and is the body of Christ in the world; and the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper are means of grace.

During the 1970s, Good News focused upon seminary education, launching Catalyst (now published by AFTE), funding worldwide missions, and engaging “theological pluralism” with the “Junaluska Affirmation,” an orthodox statement on Wesleyan theology. Good News requested time before the Association of Deans and Presidents of United Methodist Seminaries to present its concerns in more detail. This request was denied. However, the association did indicate receptivity to visits by seminary students, faculty, and administration.

As a result, representatives from Good News were able to have on-campus discussions with representatives of ten official United Methodist seminaries. Two seminaries turned down the request for dialogue.

As Good News celebrates 50 years of ministry within The United Methodist Church, we share the following report of Ed Robb’s speech and the creation of the Junaluska Affirmation by Dr. Riley B. Case, author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History, as a testimony to the faithfulness of men and women who sacrificially prayed for and contributed to the cause of renewing United Methodism.

–Good News

By Riley B. Case

The spirit at the 1975 Good News Convocation at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina, was exhilarating, but it was intended to be more than just an evangelical family reunion. Good News was in the business of renewal, and The United Methodist Church was experiencing very little renewal. The reports were discouraging:

• In the church’s new structure, power was concentrated in the General Board of Global Ministries, which, under domination of the Women’s Division, had declared itself on behalf of liberation theology. The Commission on Social Concerns in the former Methodist structure, controlled by persons many considered social extremists, had been elevated to the status of a board, while evangelism and education had been diminished by being subsumed as divisions under the Board of Discipleship. Youth ministry was disintegrating; curriculum sales were plummeting.

• The Church’s new doctrinal statement was serving further to undermine the Church’s historic doctrinal heritage. The seminaries were still not open to evangelical presence.

• The former Evangelical United Brethren were finding that the merger was not a marriage of equals, but a corporate takeover. EUB practices and beliefs, such as freedom of conscience in matters of baptism and infant dedication, contrary to reassurances given before merger, were being scuttled by the new Church.

These discouraging developments were being reflected in dramatic reversals in membership, worship attendance, and Sunday school enrollment.

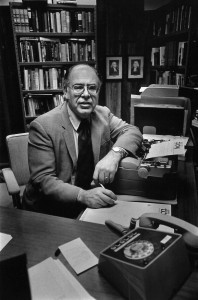

Dr. Ed Robb’s keynote address at the 1975 convocation spoke to the evangelical discontent with the seminaries. The presentation, entitled “The Crisis of Theological Education in The United Methodist Church,” linked the problems of the Church to leadership and the problem of leadership to the seminaries: “The question is, who or what is responsible for this weak leadership. I am convinced that our seminaries bear a major portion of the responsibility. If we have a sick church it is largely because we have sick seminaries.”

Among the litany of failings and shortcomings linked to the seminaries, Robb further charged: “I know of no UM seminary where the historic Wesleyan Biblical perspective is presented seriously, even as an option.”

Robb asked (1) that two seminaries be entrusted to evangelical boards of trustees and continue as United Methodist seminaries; (2) that in the spirit of inclusiveness, every United Methodist seminary invite competent evangelicals to join the faculties; and (3) that greater support be given to established evangelical seminaries, especially those in the Wesleyan-Arminian tradition.

The seminaries, and the Church’s Board of Higher Education and Ministry, if they even were aware of the Good News critique, were not inclined to treat the Robb challenge with any seriousness. No established “leaders” in the Church would ever even consider allowing evangelicals to operate a United Methodist-related seminary, and no seminary would allow such a radical shift in focus. And, these “leaders” would argue, the seminaries were already inclusive and diverse. Furthermore, there was absolutely no interest in supporting non-United Methodist schools, especially evangelical schools.

From the perspective of the institutional church and the seminaries, Good News was a reactionary throwback to a dead past. Though the convocation and Robb’s address were well reported, especially by The United Methodist Reporter, there was little denominational response to the events of the convocation – with the exception of Albert Outler, professor of Historical Theology at Perkins School of Theology. Dr. Outler did note the address and was offended by the Robb charges, especially the accusation that there was no seminary where the Wesleyan biblical perspective was treated seriously, even as an option.

Outler, too, was longing for United Methodist renewal. In many respects, Outler was “Mr. United Methodist” of the 1970s. He had chaired the Study Commission on Doctrine and Doctrinal Standards for The United Methodist Church. He had lectured bishops and represented the Church in ecumenical councils. In his lectures at the Congress on Evangelism in New Orleans in 1971, Outler recognized a growing evangelical renaissance, the sterility of liberalism, and sought to call the Church to an authentic Wesleyan theology.

In the lectures, however, Outler was not pleased with much of evangelicalism, especially with that offered by Good News: “[T]hese fine old words [‘evangelical,’ ‘evangel’] have … generated many a distorted image in many modern minds – abrasive zealots flinging their Bibles about like missiles, men (and sometimes women!) with a flat-earth theology, a monophysite Christology, a montanist ecclesiology and a psychological profile suggestive of hysteria.”

It is no wonder Outler reacted strongly to Robb’s address. In a letter to The United Methodist Reporter, Outler expressed his unhappiness: “I was … downright shocked by one of the quotations. It is sad that a well-meaning man should lodge a blanket indictment against the entire lot of United Methodist theological schools in terms so unjust that they are bound to wreck incalculable damage to the cause of theological education in the UMC – which is, as we all know, in grave enough peril already ….

“What shocked me, though, was Dr. Robb’s reported declaration: ‘I know of no United Methodist seminary where the historic Wesleyan biblical perspective is presented seriously, even as an option.’ The point, of course, is that, since Dr. Robb knows of Perkins, he has said, by strict logical entail, that the historic Wesleyan biblical perspective is not presented seriously at Perkins, ‘even as an option.’

“Now, either the phrase ‘historic Wesleyan biblical perspective’ means something that neither I nor other Wesley scholars – here and elsewhere – understand or else this accusation is simply false …. I can think of many ways in which a much needed, candid debate about Methodist theological education could have been stimulated and helped ahead; Mr. Robb’s way resembles none of them.”

Even Spurgeon Dunnam, editor of The United Methodist Reporter, was taken aback by the forcefulness of the Outler letter and contacted Robb for a response. Robb wrote a response but believed more was needed. Robb called Outler and asked if he might come to see him. Outler, according to Robb, had to think about that request for awhile before he gave grudging consent. And so it was that Ed Robb and Paul Morrell, Good News board member and pastor of Tyler Street Church in Dallas, made their call on Outler at Perkins School of Theology.

Outler gave his version of the visit in an article printed in The Christian Century: “It was … downright disconcerting to have Dr. Robb and some of his friends show up in my study one day with an openhearted challenge to help them do something more constructive than cry havoc. Needless to say, I’ve always believed in the surprises of the Spirit; it’s just that they continue to surprise me whenever they occur!

“Here, obviously, was a heaven-sent opportunity not only for a reconciliation but also for a productive alliance in place of what had been an unproductive joust. Moreover, as we explored our problems, some unexpected items of agreement began to emerge.”

Thus began an unlikely friendship and alliance that would eventually lead to the establishment of A Foundation for Theological Education (AFTE). Outler’s friends in the academic world were willing to trust Robb because of Outler. Robb’s friends in the evangelical world were willing to trust Outler because of Robb.

Outler would later comment that AFTE was the most satisfying achievement of his life. In his own affirmation of Outler, Robb and the AFTE board, and not Perkins or Southern Methodist University, initiated the campaign to raise $1 million to endow the Albert Outler Chair of Wesley Studies at the seminary. The money was raised and the chair established.

Outler’s pluralism

Albert Outler, however, was not universally appreciated by Good News, primarily because of the 1972 doctrinal statement affirming “theological pluralism.” In some circles it was also known as the “Outler Statement.”

Good News had, from its inception, believed that the recovery of classical Wesleyan doctrine was the key to denominational renewal. Charles Keysor charged that the feature of “doctrinal pluralism” meant that “anybody was free to believe anything – with no negative limits.”

The great Methodist middle, however, was at best ambivalent, and in some cases downright hostile, to the suggestion that renewal in the Church was directly linked with a recommitment to historic doctrine. The arguments depreciating doctrine took several forms:

• Methodism was never a confessional church;

• Wesley had said, “If your heart is as my heart, give me your hand,” suggesting that Methodism was primarily a religion of experience;

• the way a Christian lives is more important than what a Christian believes;

• doctrine divides; and

• the emphasis on correct belief is judgmental and unloving.

A time of turmoil in politics, moral traditions, and social customs, the 1960s also brought with it a time of theological confusion: existentialism, personalism, fundamentalism, Death of God theology, process theology, and liberation theologies.

With the merger of The Evangelical United Brethren Church and The Methodist Church in 1968, the matter of stated doctrine had to be faced. Whether or not anybody believed in them – or even knew they existed – doctrinal statements had been carried in every Discipline of all the predecessor denominations from the first Methodist conference in 1784. What was now to be done with these statements, specifically the Articles of Religion of The Methodist Church and the Confession of Faith of the EUB Church?

The task was handed to a commission headed by Outler and board and agency representatives, several prominent pastors and laypersons, and a heavy preponderance of seminary professors, including outspoken liberals.

Good News, though still a fledgling movement when the commission was established, asked to participate in the discussions. There was not even a response to the letters that asked for Good News involvement. For his part, Outler was devoted to the commission and its task. He was also, perhaps more than any other person, aware of the problems the commission faced:

• Both churches, the Methodist and the EUB, had stated doctrinal standards, even though there was some discussion as to what precisely the standards were. For Methodists, the standards started with the Articles of Religion. But did they include Wesley’s sermons and his Notes Upon the New Testament?

• The doctrinal standards had been widely ignored, and even scorned, for a number of years. They were almost never referred to in Methodist seminaries.

• The scuttling of the EUB and Methodist statements, or the combining of the two, even if desirable, would probably not be possible, because of the restrictive clause in the constitution of the Methodist Discipline that stated: “The General Conference shall not revoke, alter, or change our Articles of Religion or establish any new standards or rules of doctrine contrary to our present existing and established standards of doctrine.”

The Outler solution was ingenious. Do not tamper with the restrictive clause (this would be a long, complicated, unproductive, and probably unsuccessful constitutional engagement), but write an additional statement that would interpret the doctrinal standards, placing them in historical perspective, and letting them inform the present task of theologizing even as they did not inhibit that task. Then call the Church to a new challenge to theologize and, in the process, to restate the doctrinal tradition while all the time making doctrine relevant for the present time.

The emphasis of the new statement would not be on content, that is, on the actual teachings of Methodism and Christian faith, but on process, that is, how the Church went about determining what it believed: “In this task of reappraising and applying the gospel, theological pluralism should be recognized as a principle.”

The 1972 General Conference approved the report of the Doctrinal Commission 925-17 without amendment and without discussion. No Good News voice, nor any evangelical voice for that matter, nor any voice from any perspective, even raised a question about the report or the ideas therein. After accepting the report that asserted that The United Methodist Church was not a creedal or confessional church and that pluralism was the guiding principle that would inform future doctrinal discussions, the conference moved immediately to “the social creed,” and social principles in an extended floor debate that lasted six hours. During that time, the thought that diversity or pluralism might also apply to the Church’s social stances was not expressed even once.

The Good News board was devastated by the lopsided approval of the doctrinal commission’s report and the fact that it was received so nonchalantly.

The summer 1972 issue of Good News carried a twelve-page report on General Conference written by Chuck Keysor. Five of the pages were devoted to the doctrinal statement. Quoting reports in Engage magazine and the Texas Methodist, he also argued that the statement was a revocation and alteration of the present doctrinal standards and was thus in violation of the restrictive rule in the Discipline.

Dr. Outler was scandalized by the Good News evaluation. In true Outler-style, he wrote Keysor: “Your surprisingly harsh and reckless comments on the new UMC Doctrinal Statement … have left me utterly appalled. I had not, of course, ever hoped for your positive approval, but I really had thought you might have been willing to recognize our positive efforts to make room for both conservative and liberal theological perspectives in the United Methodist Church. … There is, therefore, something tragic in your reckless and total rejection of us, since it forecloses any possibility of further meaningful dialogue. This, in turn, can only result in mutual loss, to all of us and to the church as well.”

Keysor responded in true Keysor style: “We find it ironic to hear you saying that our editorial shuts the door to dialogue. As I have already named, there was no dialogue from you until after the editorial, so it seems that publishing more editorials is the way to increase dialogue.”

Good News was not opposed to pluralism or diversity as such, but insisted that pluralism needed to operate within carefully defined limits, or an essential core of truth. Otherwise, nothing would be unacceptable as United Methodist teaching. Outler and the commission insisted that there was an essential core but never defined what it was. To Good News and others, this was like the proverbial emperor’s new clothes; one might claim to see them, but they weren’t really there.

Outside observers as diverse as Christianity Today and Time magazine understood this quite well. The Time magazine report of the General Conference noted: “The Outler commission’s solution qualifies the traditional creeds – Wesley’s Articles and the E.U.B. Confession of Faith – with explanatory statements warning that they should be interpreted within their historical context. The statements maintain that Wesley and the E.U.B. patriarchs made “doctrinal pluralism” a major tenet and held to only a basic core of Christian truth – but the statements stop short of specifying what that core was.”

With its stand clearly taken, Good News was willing to stay the battle. As Keysor editorialized in the summer issue of Good News in 1972: “What are evangelicals to do, in the aftermath of Atlanta? Many are quitting, feeling that the United Methodist Church has abandoned and betrayed Christ, the Gospel and its members.

“Good News feels deep sorrow and pain at the exodus of these brothers and sisters in Christ. We do not condemn any person for following God’s leading, but we feel strongly that God calls us to remain. This has been our motive from the start…. To separate or not to separate, that is the basic issue. And so we feel it desirable to share with readers why we believe the most important place for evangelicals is inside the United Methodist Church.”

Keysor’s reasons for staying reflected a remnant kind of thinking: “In the past (God) has worked miracles through tiny remnant groups which fear only displeasing the One who has called them – the One whom they know as Father. Who cares if we are a small minority? Numbers and success are pagan preoccupations. To gain control of the denominations means nothing; to be faithful to Jesus Christ means everything.”

Junaluska Affirmation

Chuck Keysor and Albert Outler had an intensive two-hour conversation when Outler came to Asbury Seminary in March 1974 to deliver a series of lectures on Wesleyan theology. In a detailed account of the conversation shared with a few members of the board, Keysor offered his impressions of Outler reacting to Good News concerns: Though Outler strongly believed in a core of irreducible doctrinal truth, he also believed that attempts at doctrinal definition “always result in inadequate conceptions of ultimate realities” (propositional statements demanding allegiance smacked of fundamentalism). He admitted, basically, that he was not interested in a specific of “core” essential doctrine, even though he believed the Church could refer to such a core.

Outler, however, was at least pleased that someone was willing to discuss doctrine and offered his own suggestions as to the sorts of actions Good News might pursue.

l. Good News could test the seminaries’ resistance to pluralism by underwriting the education of several outstanding young scholars who would take degrees at such institutions as Yale, Chicago, or Oxford in such areas as patristics, historical theology, and New Testament and, then backed by impeccable credentials, go to the Board of Higher Education and ask if there is any discrimination because of their conservatism (this would soon become the strategy of A Fund for Theological Education [AFTE]).

2. If the Church really wanted a descriptive statement of the “core” of essential United Methodist doctrine, it could do so by amending or altering the present statement with a 51 percent vote of the General Conference (this, in fact, would soon become the Good News legislative strategy in coming General Conferences).

3. Outler’s intent in the 1972 statement was to sketch broad theological generalities and encourage “theologizing,” in which identifiable groups in the Church would delineate their own essential core – what they would be willing to die for.

It was this third suggestion that gave additional impetus to a Good News effort, already being discussed and planned, to offer a contemporary evangelical statement of the essential core of Wesleyan doctrine for United Methodism. To do this, Good News called upon Paul Mickey, Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology at the divinity school at Duke, to lead a committee to draft a statement. Good News leaders such as Chuck Keysor, James V. Heidinger II, myself, and Lawrence Souder were joined by Dr. Dennis Kinlaw, president of Asbury College and Dr. Frank Stanger, president of Asbury Seminary, to draw up the statement.

The Junaluska Affirmation would be an evangelical response to the 1972 doctrinal statement’s invitation for groups to engage in theological discussion and affirmation, seek to identify the “core of doctrine” that the 1972 statement alluded to but never defined, and serve as a rallying point for evangelicals in the Church.

Before the final draft, the statement was shared with Albert Outler. He was obviously pleased that at least one group was taking the 1972 statement seriously enough to draw up a doctrinal statement. In response, Outler wrote: “Thanks for that copy of the ‘draft statement’ of ‘Scriptural Christianity for United Methodists.’ I’ve read it with care and real appreciation. This is an important response to that invitation … I welcome the venture, even as I have found it interesting and edifying. Power to the project – especially in its tone and temper!”

Outler continued with an eight-page critique of the statement. His critique perhaps said more about his own theology than the work of the committee. Outler argued that the approach of the statement, that is, the organizing of essential doctrines around themes of systematic theology (sin, God, atonement, Jesus Christ) was not Wesley’s approach, who rather located the “essentials” in the proclaiming of the holy story.

The statement was made available at the 1975 Good News Convocation at Lake Junaluska, where it was discussed in small groups, adopted by the assembly gathered, and became known as the Junaluska Affirmation.

The United Methodist Reporter editorialized positively on the Junaluska Affirmation and printed it in full. UMCom, the official United Methodist news service, commented briefly that the “affirmation” had been adopted and added remarks from Paul Mickey about the need for ‘theological clarity in a time of theological confusion” and from Good News referring to the doctrinal standards and the ancient creeds as the “foundation for historic faith.”

There was some disappointment on the part of Good News that the affirmation failed to stir up either reaction or critique or comment from the larger Church. It was pointed out, however, that except for the bishops – given the charge in the Discipline “to guard … the apostolic faith” – no board or agency or group in the Church felt ownership or responsibility for doctrine. It was not so much that the general Church agreed or disagreed or affirmed or denied the Good News doctrinal effort. It was rather that it just did not care that much.

Later, the September 1975 issue of Interpreter magazine carried an editorial by Roger Burgess entitled “Has Good News Become Bad News?” Burgess did not critique the Junaluska Affirmation but was uneasy that Good News should draw up a statement in the first place. He concluded: “I find it hard to discover much that is constructive or loyal in these actions and proposals.”

As far as Good News was concerned, the Burgess comments were a misreading of the intent of the Junaluska Affirmation and of the purpose of Good News. But for once, Good News was secure enough it did not need to be defensive about the accusations of the editorial. It would direct its energies from this time forth not needing to define who it was, but in understanding and seeking to bring renewal to The United Methodist Church.

And the task, at least as it related to doctrine, was formidable. The general Church, already in a state of doctrinal confusion, seemed to be able to make no sense out of the 1972 statement. The attempts to clarify seemed only further to obfuscate. In 1976, the General Board of Discipleship published the pamphlet “Essential Beliefs for United Methodists.” It was to be an attempt to interpret to local churches and individuals the 1972 doctrinal statement.

The pamphlet managed to feature “essential beliefs” without the first mention of doctrinal standards or of the Articles of Religion or the Confession of Faith or of the sermons of Wesley. The one belief that seemed more essential than all others was the belief that “our strength comes through unity in diversity rather than through rigid uniformity.”

If there were “essential beliefs,” they were what we were to formulate for ourselves (the opening sentence was, “Our beliefs grow out of our experiences”), based on the quadrilateral: Scripture, Tradition, Experience, and Reason. These core beliefs evidently had nothing to do with Christ’s death on the cross for our sin or, for that matter, Christ’s death on the cross for any reason. Nor did it refer to the Resurrection, to salvation, justification, sanctification, heaven or hell, or to the New Birth. At least none of these were even mentioned.

The pamphlet was obsessed with the importance of the quadrilateral, and that discussion took twelve of the sixteen pages. It spent time with sacraments and mentioned creeds, but only with the discounting qualification that “the living God cannot be reduced to or contained in any creed.”

But, according to the pamphlet, the Church was not without stated beliefs. United Methodists did have agreement, if not about doctrinal beliefs, then on the social principles. “Essential Beliefs for United Methodists” closed with the Social Creed prefaced with the words: “Our Social Creed provides a summary of our beliefs as United Methodists.”

Good News had a long and laborious task ahead of it.

Riley B. Case is the author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon). He is a retired United Methodist clergy person from the Indiana Annual Conference, the associate director of the Confessing Movement, and a lifetime member of the Good News Board of Directors. This essay is adapted with permission from Evangelical & Methodist.

0 Comments