On Contemporary Wesleyan Essentials –

By David F, Watson –

“In essentials unity; in non-essentials liberty; in all things charity.”

Christians have recited this maxim at least since the seventeenth century. There is real wisdom here. It does, however, compel us to ask the question, “Which of our faith claims are essentials?” As Methodists, we can divide this question into two parts.

First, we can ask which claims are essential for Christians broadly speaking – essential for the Church universal. Second, we can ask which claims define us particularly as Methodists. These are matters we Methodists have wrestled with publicly for at least the last century, and it will help us to gain clarity on them as we proclaim the Good News in the post-Christian West.

Getting at the “Essentials.” Like most other Western Christians, Methodists experienced the pressures of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy in the early years of the twentieth century. Fundamentalism, with its insistence upon both biblical inerrancy and premillennialism, wasn’t always a good fit for Methodists, even conservative ones (see Matthew’ Sichel’s article, “Methodist Fundamentalists and Modernists: A New Look at an Unfinished Controversy,” in Firebrand, Nov. 22, 2022).

In 1922, Harold Paul Sloan (1881-1961), a leading member of the New Jersey Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, published a work called Historic Christianity and the New Theology (The Pentecostal Publishing Company, 1922). In this work, Sloan proposed six affirmations he deemed essential for Christian faith:

• The Bible: A divine supernatural revelation brought to its climax in Christ through his apostles, which abides as the only and sufficient rule of faith and practice.

• Depravity: That at the beginning of history man sinned and fell, and that as a result he is universally abnormal in his moral and spiritual life, capable of being restored only by a supernatural work of God.

• The Incarnation: That the Eternal Son of God took on himself human nature in the womb of the Virgin.

• The Atonement: That by his death on the cross Jesus achieved forgiveness of sin for all who will believe.

• Justification by faith alone: That by a personal and ethical trust in the grace of God at the point of Christ’s redeeming work man receives complete salvation; and that salvation is conditioned by such a faith and by nothing else. Good works thus become the fruit, and not the condition of salvation.

• Regeneration: a supernatural work of God whereby we are spiritually renewed and made to feel the reality and glory of the moral and spiritual universe, and of God and of our Savior.

• The Second Coming of Christ, the resurrection and the final judgment.

Rather than identifying with the fundamentalist movement, Sloan called his position “essentialism.” His affirmations regarding biblical inspiration and atonement allowed for more latitude than those of the fundamentalists. In good Methodist form he added belief in the depravity of humankind, justification by faith, and regeneration.

The six essentials Sloan listed constituted a proper rendering of Methodist doctrine. Yet while he did have some success in his lifetime leading the essentialist movement, even publishing a journal called The Essentialist, Methodist essentialism does not seem to have outlasted him. Hence we see the Rev. Charles Keysor (1925-1985) making a similar proposal forty-four years later.

The Good News renewal ministry was born out of Keysor’s 1966 article, “Methodism’s Silent Minority” (Christian Advocate 10.14 [1966], 9-10; for more on this history, see James V. Heidinger II, The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism, Seedbed, 2017). In this article, Keysor writes that this minority is “not represented in the higher councils of the church…. Its concepts are often abhorrent to Methodist officialdom at annual conference and national levels.” It consists of “those Methodists who are variously called ‘evangelicals’ or ‘conservatives’ or ‘fundamentalists.’ A more accurate description is ‘orthodox,’ for these brethren hold a traditional understanding of the Christian faith.” He describes “a deep intolerance toward the silent minority who are orthodox” and notes the great irony of such intolerance within a denomination so focused on ecumenism.

To define the most basic claims of orthodoxy, Keysor referred to the “five fundamentals,” a term coined at the Niagara Bible Conference of 1895 and utilized by fundamentalist groups over the next century. The five fundamentals Keysor lists are: (1) inspiration of Scripture, (2) the virgin birth of Christ, (3) the substitutionary atonement of Christ, (4) the physical resurrection of Christ, and (5) the return of Christ. He thus draws upon common evangelical affirmations, though unlike most renderings of the “five fundamentals” he affirms the inspiration of Scripture, but not its inerrancy. Keysor was not truly a fundamentalist, but, like Sloan, an essentialist.

Do We Need Essentialism? Some might suggest that Methodist essentialism was unnecessary. After all, we already have the Articles of Religion and, beginning in 1968, the Confession of Faith. Since we have these statements of doctrine, why would we need to identify a list of “essentials”? Others will insist that essentialism was too rigid. Methodism, they will say, is a faith in which we “think and let think.”

As for the first of these objections, we do indeed have doctrinal standards. Why, then, would we need a list of “essentials”? One reason is that the Articles and Confession sometimes use rather technical theological language and offer more detailed descriptions of our beliefs than can be easily memorized. Put differently, they aren’t the most user-friendly documents in the world. It can thus be helpful to supplement them with a short, accessible account of our basic truth claims. As for the second objection, the idea that Methodism is non-creedal is simply a convenient fiction. It is not true, nor has it ever been. The Articles of Religion, the Confession of Faith, Wesley’s sermons, and his Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament presuppose the creedal faith of the Great Tradition.

Methodism has long been in an identity crisis, and both Sloan and Keysor recognized this. While the fundamentalist-modernist controversy doesn’t map neatly onto Methodism, we Methodists have been divided between those who wish to revise the long-held teachings of the faith and those who wish to preserve them.

The crisis has not been one of simply defining Methodist belief, but Christian belief. Who is the God we worship? What is this God like? Who is Jesus? What is his significance? In what kind of actions does God engage? Is God capable of, and willing to, act directly and powerfully in our lives? These kinds of questions characterize the debate between theological liberalism and theological orthodoxy that began in the eighteenth century. Sloan and Keysor stood up for the apostolic faith handed on to us across the centuries, and we owe them a debt of gratitude.

Christian Essentials and Methodist Essentials. While I appreciate the efforts of Sloan, Keysor, and other like-minded Christians, I don’t think there is a need to create a new list of Christian essentials. It is nothing new to create short statements summarizing the essential truth claims of Christian faith. The early church did this with the Rule of Faith, and later with creeds. The Apostles’ Creed, a baptismal creed, is the best example of this. It affirms God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and then affirms belief in the church, the communion of saints, forgiveness, the resurrection of the body (Jesus’ and ours), and eternal life. This creed has served the church across the centuries, and it suffices as a statement of basic Christian truth claims. If we want to identify the basic contours of Christian orthodoxy, the Apostles’ Creed is a time-honored guide.

But what about Methodism? Methodism is more than mere orthodoxy. It involves (or should involve) assent to the Great Tradition of Christian faith embodied in her creedal tradition, but it also has its own particular emphases. In other words, Methodists, Calvinists, Lutherans, and Roman Catholics can all recite the Apostles’ Creed, but we also hold certain beliefs that mark us out as distinct communities of faith. Sometimes we hold beliefs clearly different from one another.

Calvinists hold that individuals are predestined for heaven or hell. Methodists do not believe this. Roman Catholics believe that the bread and wine of the Eucharist become the actual body and blood of Christ. Methodists do not believe this, though we do affirm the real presence of Christ in communion. Often, however, we simply differ in what beliefs we emphasize. For example, most Christian traditions affirm some form of sanctification, but for Methodists this belief is particularly important.

What, then, are those beliefs and emphases that mark us off as a community of faith? In the spirit of Sloan and Keysor, I suggest the following list of Methodist essentials. Please note, though, that I’m only dealing with doctrinal issues here. There are other issues of organization and church governance, such as connectionalism and bishops, that are also important, but not strictly matters of doctrine. (On bishops, for example, I addressed the issue in, “‘A Spirit of Governance’: On Bishops in the Global Methodist Church,” for Firebrand, January 10, 2023.)

1. Depravity – All human beings labor inescapably under the power of sin, and only by the grace of God can we repent and turn to Christ.

2. The Freed Will – Through preventing (or prevenient) grace, God makes it possible for us to turn from sin and accept Jesus Christ.

3. Justification by faith – We are made right with God by faith in Jesus Christ.

4. Sanctification – By the power of the Holy Spirit, we can experience the new birth. God will begin to restore the divine image within us that has been tarnished by sin. We should expect even to experience the gift of perfect love (Christian perfection, or entire sanctification).

5. Sacramentalism – Baptism and the Lord’s Supper are means of grace, whereby the Holy Spirit empowers us and leads us into salvation.

6. Scripture – Scripture is inspired by God to lead us into salvation. It is the true rule of Christian faith and practice, infallible in all matters related to salvation and the attendant life.

Moving Forward. No group, and particularly no faith community, can thrive without a clear sense of its identity and purpose. For a time, Methodists in America could count on the momentum generated by the rapid growth of the movement during the Second Great Awakening. We could rely as well on a culture that was friendly to Christian belief and where being a Christian was broadly seen as a good thing. Times have changed. The church of yesterday isn’t coming back. We’re going to have to be as clear about who we are, what we believe, and what our goals are as those first Methodists who gathered around John Wesley in the mid-eighteenth century.

The fields are white and ready to harvest, but are we ready to harvest them? If we’re going to preach the good news, we’re going to have to know and understand the good news ourselves. .

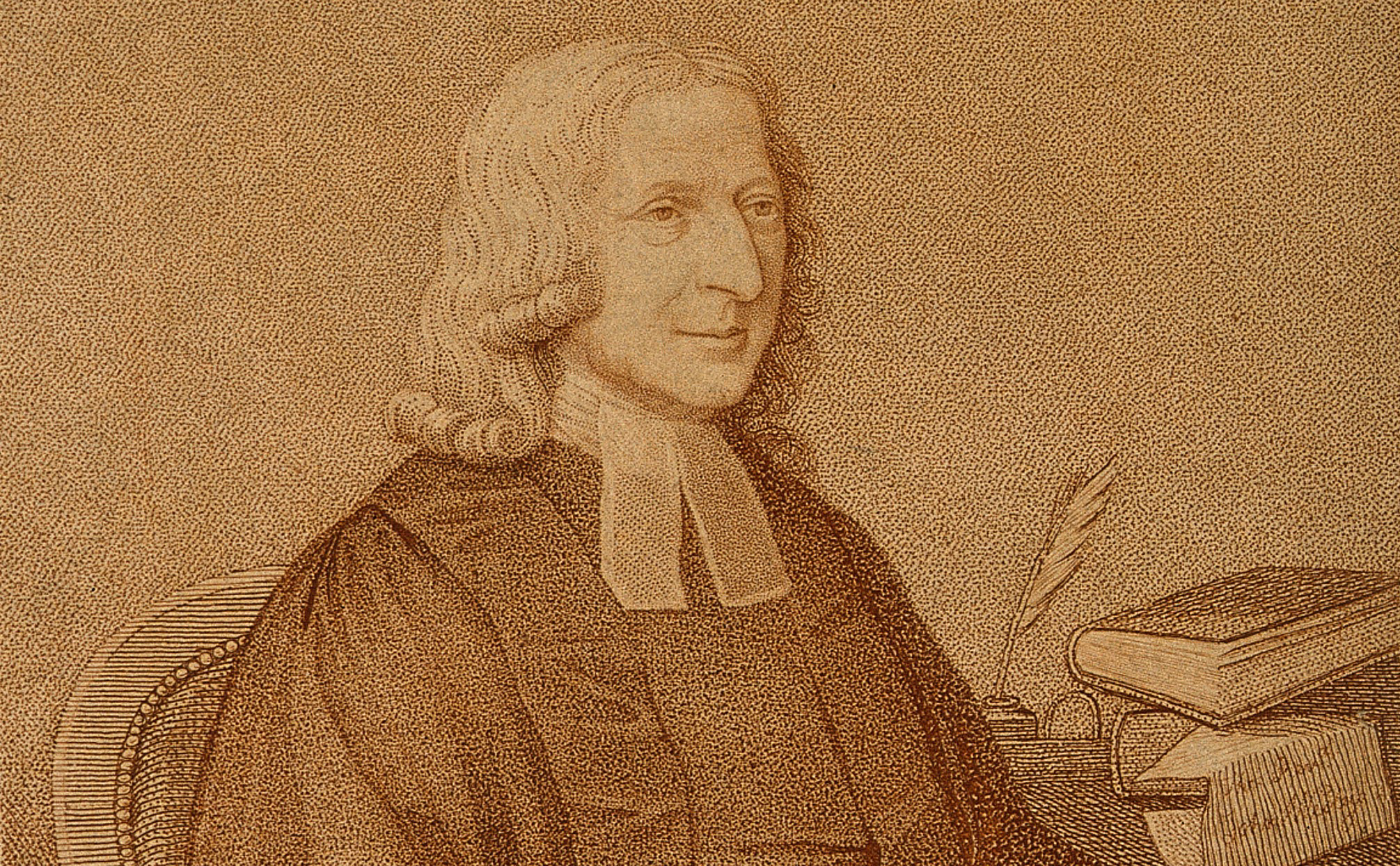

David F. Watson is Academic Dean and Professor of New Testament at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the lead editor of Firebrandmag.com and an elder in the Global Methodist Church. Art: Stipple engraving of John Wesley by Francesco Bartolozzi after Johann Zoffany, 1760.

Excellent article. You have correctly identified the primary issues which have divided our movement since 1968 as well as well before. One question: can you elaborate on your statement on infallibility? I am unclear as to your meaning. Thank you for your work. You are helping to lay a firm theological and doctrinal foundation for this new movement in Methodism.

In evangelistic or missionary point of view to save the souls it was essentially soteriological understanding of the 3 Wesleyan essential doctrines, because soteriology was never separated from christology or eschatology or trinity or discipleship (Mat.28,19-20).

For example the doctrine of Original sin is the first Wesleyan essential doctrine and it is the revelation that all the time only God the Father is good, holy and full of grace and we are by nature born without God in this world and need new birth from above from God to live a holy life as his family (his chosen people) and his church (ecclesiology).

The second essential doctrine is personal justification by faith in Christ Jesus the Lord of all due to the most expensive personal but not private reconciliation grace that He loved me and gave his life and died to save me even to the uttermost and forevermore to be with me, as he is coming, was and will be Emmanuel (God with us). Without him and this eschatology we can’t, but together with him (faithfully to him) we can do every will of God.

And the last Wesleyan essential doctrine is sanctification that begins with the new birth from above and is the initial realisation of the things hoped for (resurrection, new creation, eternal life), it is the witnessing of the holy Spirit with our Spirit that we are children of God and it is the blessed assurance in his providential guidance and eternal predestination. This I would say soteriological predestination is best revealed in John 3,16 that God so much loved the world, not less nor more then that, that this love is revealed in Christ Jesus only through faithful belief only in his most expensive grace only.

Therefore soli deo gloria as well for John and Charles Wesley means as in Psalm 115,1 glory or praise not to the name methodists or christians or to our own names, but glory only to God (further see please as well John 5,44 and John Wesleys Note upon this vers).

What I appreciate about Sloan and Keysor’s efforts is that they don’t conflate Methodism with Wesleyanism. While the Wesleyan branch of the movement certainly constitutes the majority, there have always been—are are still today—Methodists who don’t hold to Wesley’s personal distinctives, nor should holding Wesley’s distinctives be requisite to claiming the name “Methodist,” in my view. This is an unpopular position for which I’ve received much flak in the conservative Methodist social media groups, but it simply seems historically inaccurate and dishonest to use “Methodist” as a mere synonym for “Wesleyan.” Wesleyanism is a vital expression of Methodism—indeed, the major expression, numerically—but it isn’t the whole of Methodism. Methodism is something bigger. “Methodism” must include the descendants of Whitefield, Harris, Rowland, Grimshaw, Venn, Madan, Romaine, Haweis, Lady Huntingdon, and the many other leaders of the Great Awakening who didn’t see eye-to-eye with Wesley on his distinctive points. Sloan and Keysor’s frameworks fit both branches of the historic Methodist family tree. The more early Methodist literature I read, the more clear is seems to me that Methodism at its root is a fervent, highly spiritual form of orthodox Protestantism that emphasizes the sinfulness of unregenerate humanity, salvation by faith alone, the necessity of the New Both, the centrality of the Bible in Christian thought and activity, and the importance of holy living. I think Sloan and Keysor’s summaries cover that well enough. While I appreciate the desire to spell out Wesleyan essentials, it seems to me that Wesleyan essentials are Wesleyan essentials, not definitive for Methodism more broadly and historically conceived. I (an ordained Methodist elder) consider myself a variety of Wesleyan, but I don’t expect every orthodox Protestant who claims the name “Methodist” to agree on all the points on which the earliest Methodists themselves didn’t have unity.