![Taking Theological Liberalism Seriously]()

by Steve | Nov 28, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2017

By David Watson-

By David Watson-

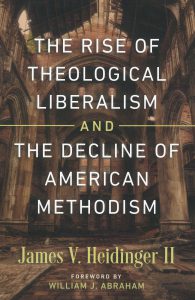

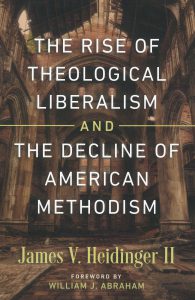

“The more things change, the more they stay the same.” That was the refrain that echoed through my mind again and again as I read through James Heidinger’s new work, The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism (Seedbed). The theological disagreements — some would say crises — that we face in The United Methodist Church today are nothing new. They did not begin twenty or thirty years ago. They did not begin with the introduction of the so-called “Wesleyan Quadrilateral” into the United Methodist Book of Discipline in 1972, or even with the formation of The United Methodist Church in 1968. Rather, Heidinger argues, they stretch back to the late nineteenth century, when the influence of German philosophy and theological liberalism began to make its mark on the Methodist theological landscape in the United States.

The premise of this book is straightforward: “the era of the early 1900’s in American Methodism was the critical period in which Methodism experienced major doctrinal transition, revision, defection, and even denial of her Wesleyan doctrinal heritage.” This era saw the rise of both theological liberalism and the social gospel, two distinct but related movements. Since this early period of revision, the disproportionately large influence of liberalism upon American Methodism has continued to erode its doctrinal foundations. Such doctrinal erosion lies at the root of our decline.

Heidinger distinguishes between two uses of the term “liberalism.” In one sense, liberalism can mean, “a spirit of openness, graciousness, or liberal-mindedness.” The liberalism he takes up in his book, however, is different from this. It is “a movement during the early 1900’s that challenged and soon displaced the very substance of the church’s classical doctrine and teaching.” This theological movement replaced traditional teachings of the church with ideas more palatable to the “modern” mind. It dispensed with miracles and the supernatural, made Jesus primarily a moral exemplar, replaced the pervasive sinfulness of humanity with a notion of innate human goodness, and therefore rejected traditional understandings of Christian atonement.

The book consists of an introduction and thirteen chapters, preceded by a very helpful foreword by Professor William J. Abraham. The opening chapter sets the table: sound, scriptural doctrine is essential for our identity as the body of Christ. There will be no true spiritual renewal without theological renewal.

The next two chapters begin the critique of the liberal tradition. Here Heidinger describes the intellectual climate of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and some of the effects it had upon Methodist doctrine and theology. As more and more Methodist academics went to study in Germany, they brought back to the United States a brand of modernist theology popular in Germany at the time. Particularly influential were theologians Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) and Albrecht Ritschl (1822-1889). Their teachings would find a firm foothold in the Methodist academy of the early twentieth century.

As one would expect, the introduction of these theological innovations would create controversy. In Chapter 4, Heidinger describes the resistance that began to emerge among Methodists who objected to the revision of orthodox Christian doctrine by Methodist theologians. This resistance included the formation of the Methodist League for Faith and Life under the leadership of Harold Paul Sloan of the New Jersey Conference. Heidinger draws a striking parallel to our situation today: “The Board of Bishops continued to present a united front in its relationship to the Modernist/Liberalism controversy within the church, even though some bishops were aware of, and distressed by, the church’s doctrinal unfaithfulness…. [W]hen challenged and urged to act on behalf of doctrinal faithfulness and confront the matter head-on, they opted instead for a facade of unity as a Board of Bishops rather than choosing to contend for the faith that was under attack.”

Methodist leaders of this period chose by and large to avoid controversy and conflict. They were “determined to avoid the ugliness and bitter controversy of heresy-hunting that they saw taking place in other major denominations.” Instead, they attempted to develop an ethic of openness and tolerance, and therefore relaxed membership standards and baptismal vows. They also devalued creedal formulations. Heidinger takes up these trends in the next chapter. During this period there was a strong push to cast Methodism as a “non-creedal” tradition, and to affirm faith lived out through acts of love, deemphasizing any doctrinal confessions of faith. Boston University’s Borden Parker Bowne (1847-1910), a key figure in the development of the deeply individualistic philosophy of “personalism,” exerted far-reaching influence on Methodist theology in the United States.

In Chapter 6, Heidinger describes more specifically the contours of the theological liberalism that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was, he maintains, a new form of Christianity characterized by a rejection of all of the supernatural elements of our faith, a negation of most traditional Christian doctrines, and an emphasis upon the moral teachings of Jesus. This leads to a discussion in the seventh chapter of the social gospel, a theological and ecclesiological movement meant to address problems of rapid urbanization in the early twentieth century. In the absence of clear doctrinal teaching, many Methodists began to see the formation of a just society as the basic goal of Christian faith.

Chapter 8 recounts the internal tensions and divisions one might expect from such theological upheaval, including tensions between clergy and laity, the rise of the Holiness Movement, and the battle fatigue created by these disagreements. A sort of classism developed among Methodist clergy in the early twentieth century. Drawing upon a 1926 article in the Christian Century, Heidinger refers to three “grades” of Methodists. The upper grade consisted of “seminary professors, agency heads, bishops, [and] denominational leaders,” most of whom were seminary graduates and theologically liberal. The second grade was made up of clergy who “aspired to be part of the upper grade, but who had probably come into the ministry through the Conference Course of Study.” In other words, they were not seminary graduates, and therefore had not received the same intellectual and theological formation as those who had been to seminary. The third grade consisted of “pastors with limited formal education who served the smaller and more rural churches with the smallest membership and least amount of financial resources.” Among the second and third grades, which were much more traditional in their beliefs, there arose strong opposition to the theology and leadership of the upper grade. Despite these dangerous tensions, however, the denominational leadership was reluctant to take any definitive action, opting in most cases to try to “keep the peace.”

The following two chapters describe the evangelical presence within Methodism that remained despite the liberal proclivities of denominational leaders, as well as evangelical responses in the form of various protest and reform movements. In this chapter, Heidinger introduces the “great deep” of Methodism, a term he will use many more times throughout the book. By this, he means to refer to the vast majority of Methodists (now United Methodists) who profess the historic Christian faith. While many “higher-ups” in the denomination have coalesced to the theological trends of the day, the great deep maintains the faith once for all delivered to the saints.

In Chapter 11 Heidinger begins to move into more recent decades. He describes the broad dominance of liberal perspectives in our seminaries (though there have been exceptions) and discusses theologian Thomas Oden’s critique of United Methodist theological education. He also recounts the beginnings of AFTE and the John Wesley Fellows, an initiative intended to identify and support promising evangelical graduate students who could go on to teach in United Methodist institutions. This is followed by a chapter describing the “trivialization of doctrine,” in which Heidinger focuses primarily on the 1993 Reimagining Conference and the controversy surrounding the dissenting statements of Bishop Joseph Sprague.

The final chapter discusses the importance of “getting the gospel right,” emphasizing the traditional Christian faith as a key element of both vibrancy and unity. Seven appendices include the texts of statements issued by conservative/evangelical constituencies of The United Methodist Church in response to the ongoing challenge of the erosion of doctrine in our tradition.

For those who are versed in the denominational struggles besetting The United Methodist Church, many of the themes of Heidinger’s analysis should sound familiar. The disconnect between the seminary-educated and the laity, the reticence of the bishops to address the theological conflict that exists in our denomination, the ongoing attempts to “keep the peace” at the expense of theological coherence and integrity, and deflationary notions of both doctrine and Scripture are very much part of the warp and woof of Methodism today.

Heidinger zeroes in on a key factor in the erosion of Christian doctrine within Methodism: the influence of modernist thought on Methodist academics, particularly those who had studied in Germany. Many of the presuppositions of German liberal theology struck at the very root of Christian orthodoxy. Particularly significant was the rejection of what we often call “miracles” or the “supernatural” – God’s direct intervention into the nexus of human history. Once Methodist theologians began to devalue such beliefs as the Incarnation, the pervasiveness of human sinfulness, Christ’s atoning work on the cross, his bodily resurrection from the dead, and the divine inspiration of Scripture, it was only a matter of time before our tradition would begin to lose its bearings. We no longer had the compass of the historic faith of the Church catholic to guide us.

Heidinger’s discussion of the influence of German liberal theology on American Methodism is both pointed and insightful. We cannot, however, lay theological liberalism entirely at the feet of the Germans. The skepticism of French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) had a profound effect upon subsequent philosophy and theology. Likewise we should not underestimate the influence of both British Deism and the English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), who developed the philosophical basis for the liberal tradition of process theology. Theologians of the twentieth century were forced to reckon with the evolutionary theory born of the writings of English scientist Charles Darwin (1809-1882), and this was no small matter. The liberal theology of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century emerged from the insatiable intellectual hunger of the European Enlightenment, and its influence upon both philosophy and theology in the United States was simply unavoidable.

Understanding the pervasive influence of Enlightenment thought upon American academics, however, makes clearer one of Heidinger’s more salient points: when we were faced with theological challenges, the responses of our denominational leaders was time and again inadequate. Rather than providing intellectual responses to theological claims that struck at the root of our faith, many leaders simply capitulated, even hailing these beliefs as liberators from a benighted past. These leaders did not recognize that the modern world in which they lived was itself a particular historical moment. It was no less culturally conditioned than the ancient world in which the biblical texts were written or the period of late antiquity in which so much classical Christian theology emerged. Modernist Christianity gave its own philosophical presuppositions a place of privilege, and thereby substituted a modern quest for self-actualization for the ancient story of sin and salvation that has sustained the church through the centuries. Put more simply, the problem with Methodists over the last century-and-a-half has not been that theological challenges have emerged, but that we have not faced them with sufficient theological mettle and intellectual rigor.

Another important contribution of this work is in the array of historical resources that Heidinger marshals in service to the narrative he crafts. Magazine articles, spoken addresses, meeting minutes, and other such resources make up an impressive body of historical evidence shaping and substantiating Heidinger’s claims. Many names of those who played important roles in the story of Methodism over the last century will be unfamiliar to most readers, and Heidinger helps us to recover their contributions and witness. This work helps us to understand not just how we got where we are today, but the contributions of so many who labored in service to the historic faith of the Church.

When reading this book, it is important to keep in mind that it is indeed about the rise of theological liberalism. It is not a comprehensive overview of liberalism, nor does it claim to be. It is, moreover, specifically about the rise of theological liberalism in the United States. The book wisely stays with its stated focus, and this focus itself suggests several topics in need of further investigation and elucidation. The influence of Paul Tillich and the Niebuhrs on American Methodism is surely ripe for further exploration. While Heidinger does spend some time talking about the influence of Rudolf Bultmann, the colossal influence of this figure on American liberal theology cannot be overstated, and surely bears more investigation. It would be fascinating to explore the influence of process theology, or its evangelical twin, open theism, on United Methodist theological education. Currents of liberation theology and various forms of identity-based theology also run strongly through our seminaries. To trace their influence would be a useful and interesting project.

Dr. David Watson

Many believe that our current denominational battles are about human sexuality, but that is only the presenting issue. In fact, our disagreements are much deeper. They are about theology – about the identity of God, about sin, redemption and sanctification. They are about the nature and goal of human life, the purpose of Christ’s atoning work on the cross, and what we mean when we speak of “salvation.” Heidinger is one who has taken a stand for the historic faith of the Church. He stood in the gap when many others would not. It is because of such courage, determination, and commitment to the faith of the saints and martyrs that this ancient and venerable tradition has subsisted into the present day in The United Methodist Church. I am grateful for Jim Heidinger, grateful for his witness, and grateful for this work.

David Watson is the academic dean of United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is a United Methodist clergyperson and the author most recently of Scripture and the Life of God (Seedbed).

by Steve | Nov 28, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2017

Dr. Sandra Richter, professor in biblical studies at Westmont College, teaches at Seedbed event. Photo courtesy of Seedbed.

By Heather Hahn-

Great periods of Christian revival in the U.S. need not be consigned to the church’s circuit-rider past. Even without the saddle sores and sawdust trail of yesteryear, a new generation of Christians can be just as fired up with the Holy Spirit. That’s the basic idea behind the New Room Conference, an annual event that draws together United Methodists and other Christians in the Wesleyan family to “sow for a Great Awakening.”

The phrase “is so much more than a tagline to us,” said the Rev. David Thomas, a United Methodist elder and one of the event’s organizers. “We really believe that’s the only honest expression of our need.”

Throughout the conference on September 20-22, some 1,500 Christians worshipped and heard presentations about the ways they could help wake up the world to God’s saving work. Speakers expounded on the importance of praying, relying on the Holy Spirit, engaging in Wesleyan-style small groups, and multiplying churches. Conference participants also could choose to delve deeper at a breakout session on one of these topics or a session on the Bible called “One Book to Rule Them All.”

That wasn’t the event’s only Lord of the Rings reference. Thomas called the gathering “the fellowship of the frustrated.” “We believe this restlessness is a sign of the Spirit,” he quickly added. “We are frustrated in a holy kind of way. It’s an early indicator of awakening.” The New Room Conference — named for the Methodist movement’s first meeting house in Bristol, England — is an outgrowth of Seedbed, the publishing arm of Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. Since starting in 2014, the event has grown from an initial 250 participants, and has changed venues to accommodate the bigger crowds. This year’s conference was at Church of the City, a nondenominational church in the Nashville suburb of Franklin. Next year, the event will be in a neighboring suburb at Brentwood Baptist Church, which has a bigger auditorium.

The conference focuses on matters of discipleship, not internal church debate. There are no resolutions, no speeches from the floor, and no discussions about church law and human sexuality. J.D. Walt, Seedbed’s founder and “Sower-in-Chief,” told United Methodist News Service, “This is a no-United Methodist angst zone.”

This was the Rev. Beth Ann Cook’s third year to attend. “New Room is the one conference I go to every year that fills me up, that gives me the Holy Spirit overflowing,” said Cook, pastor of First United Methodist Church in Logansport, Indiana. “This is the best drink of cold water I can imagine for someone who’s parched, and that’s why I’m here.”

The Rev. J.D. Walt, “sower-in-chief” at Seedbed. Photo courtesy of Seedbed.

The Rev. Adam Weber, lead pastor of Embrace Church in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, said he was eager to attend after watching the conference streamed online last year. “I grieved and grieved that I wasn’t there myself,” he said. This year, he not only attended but also preached about the “insane privilege to speak with God” in prayer. He is the author of Talking with God: What to Say When You Don’t Know How to Pray. “On my own, I can do so little,” Weber prayed. “But thankfully, you are God who can do so much.”

One main message repeated throughout the event: If you want to be a better disciple, join a band. By that, speakers did not mean the guitar-playing kind. Instead, New Room organizers invited people to join or form the sort of band meetings John Wesley instituted in the early days of the Methodist movement. It was an idea he got from the Moravians. Band meetings — groups of three to six people of the same gender and marital status — focus on confession. The first of five questions at a band get-together is: “What known sins have you committed since our last meeting?”

“The premise is very simple, actually,” the Rev. Scott Kisker told those gathered. “You are going to risk being known in order to risk knowing that you are loved.” Kisker and the Rev. Kevin M. Watson are co-authors of The Band Meeting, and they both spoke about the importance of such groups in their own faith development. Both men are United Methodist elders and professors at United Methodist seminaries — Watson at Candler and Kisker at United.

They explained how the meetings offer an avenue to both repent and experience God’s transforming grace in community. “The band meeting was the engine of holiness in early Methodism,” Watson said. He argued it could serve that purpose again. “When we commit that we are going to show up and do the best that we can to tell the truth,” he said, “there is a way God uses that to bring about deeper and deeper holiness, deeper and deeper healing in people’s lives.”

Throughout the New Room Conference, people who desired to be part of a band could sign up on a net hanging near the front of the auditorium. The net imagery is deliberate, organizers said. The conference is trying to form a network of bands, with at least one such group in every U.S. county.

The conference also announced a new network to support church planters. The goal is not to create a new denomination, the Rev. Timothy Tennent, president of Asbury Theological Seminary, told UMNS. “We are setting up training to help all the traditions in church planting,” he said.

For the Rev. Susan Kent, the whole event was a chance to be spiritually refreshed and see what other churches are doing. “We at our church have been doing awakening,” said Kent, pastor of women’s ministry and worship at The Woodlands United Methodist Church near Houston. “To come and see all the other churches that are being stirred by the Holy Spirit is so beautiful.”

Heather Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service.

by Steve | Nov 28, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2017

By Scott Jones-

By Scott Jones-

The recent proposal by the group “Uniting Methodists” is a welcome addition to the conversation in our church because it proposes a new form of unity that should be considered. They have put forward brief proposals in preparation for a meeting this November. Under the heading “Ordination” they say: “We call for disciplinary changes so that annual conferences are neither compelled to ordain LGBTQ persons, nor prohibited from doing so.” (Call this the AC Option). Under the heading “Officiation” they say: “We call for disciplinary changes so that clergy are neither compelled to officiate at same-sex weddings, nor prohibited from doing so.” (Call this the Clergy Option).

I have argued previously that our current crisis stems from the principled disobedience of clergy, bishops, annual conferences, and a jurisdictional conference and that we must now craft a new form of unity for Wesleyan Christians. There are several possibilities, including this one.

The “Uniting Methodists” group includes some seasoned and trusted leaders of our denomination. Unfortunately, they have chosen not to give the details of their proposals and to address how they would actually work. Perhaps their group is too diverse to agree on these at this time. That is unfortunate because we are only nine months away from the deadline for petitions to the special session of General Conference. At this stage of the discussion, proposals should be more fully developed. We are running out of time for deep analysis of serious proposals.

Another possibility is that leaders don’t want to disclose the ramifications. Some leaders in the moderately progressive part of our church believe that we need small steps like these because in the next 10 years the UM Church will become fully inclusive of LGBTQIA persons. They privately see these proposals as gently leading the church toward a conclusion they regard as both inevitable and correct. Thus, these are not stable plans for unity but transitions toward a progressive church.

Because our conversation is so important, I think two ramifications of these proposals should be named, whether or not members of the group are aware of them. Combined, they mean that their proposed new form of unity is diocesan Methodism.

The AC Option proposal would mean the end of itinerant general superintendency. Bishops right now are able to serve any episcopal area in their jurisdiction because all make sacred promises to uphold our discipline and to maintain our doctrine. Under the AC Option plan, there would be wide differences between bishops and their practices regarding homosexuality. Each bishop would have to declare his or her willingness to ordain and appoint LGBTQIA persons or not do so before an assignment to an area could be made. The most likely way to handle this is to copy the Episcopal church where each diocese elects their own bishop who serves them until retirement. Each diocese would then set its own bishops’s salary and pay its own episcopal office expenses. We would then need a general church Episcopal Fund only for Central Conferences unless the diocesan model applies there as well.

The Clergy Option would end itinerancy. Currently, all pastors are committed to preaching and maintaining United Methodist doctrine and obeying its discipline. We welcome a spectrum of interpretations but there are clear limits. For example, no United Methodist pastor can in principle refuse to baptize infants. No United Methodist pastor can in principle reject the ordination of women. We are committed to open itinerancy without regard to race or gender. Allowing an option about performing same-gender marriages means every local church would have to clarify whether they wanted a progressive or traditionalist clergy (on the issues of homosexual practice) appointed as their pastor. Coupled with the AC Option, each local church would have to specify if they were open to someone without regard to sexual orientation and gender identity. The best solution to this also comes from the Episcopal Church where each congregation chooses its own rector and the bishop has much more limited influence in the process.

Assuming the constitutional issues can be solved, (see para. 19) I welcome a debate about whether a diocesan polity is the best new form of unity we can devise. Thanks to the Uniting Methodists for putting such a bold idea on the table.

Scott Jones currently serves as the resident bishop of the Texas Conference of the United Methodist Church with his office in Houston. This editorial originally appeared at extremecenter.com and is reprinted by permission. Bishop Jones’ most recent book is The Once and Future Wesleyan Movement (2016).

by Steve | Nov 28, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2017

By Thomas Lambrecht-

By Thomas Lambrecht-

The new group “Uniting Methodists” is in the process of forming to (in their words) give voice to the “broad center” of The United Methodist Church. A recent information session about the group was held at Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kansas, led by the Revs. Adam Hamilton, Tom Berlin, and Olu Brown. “We can’t keep doing what we’re doing,” Hamilton is reported to have said. “Who’s going to speak up for that broad, middle in the center?”

It’s a good question. For the last 40 years, the “broad, middle” of global United Methodism was, of course, expressed by the General Conference. The Uniting Methodists position is that there is a “middle ground” that would allow same-sex marriage and ordination in the church, but not require it. This would effectively allow individual pastors to make their own decision about doing weddings and individual annual conferences to decide whether or not to ordain practicing homosexuals. Their hope is to keep much of the church united around this “Third Way” or “local option” approach.

There can be no discussion about the broad center of the church without actively engaging our brothers and sisters in Africa, and other locations outside North America. We are an unmistakably global church connected by a common covenant with 45 percent of United Methodists living outside the U.S. Those members are by and large conservative, and many would not be able to live in a denomination that allows same-sex marriage and ordination. When a caucus groups says it wants to construct a solution for the “80 percent of United Methodists in the middle,” they are excluding the voices of nearly half of the church.

Uniting Methodists portrays itself as a “centrist” group that welcomes people of both progressive and conservative theological perspectives and would allow the practices of both perspectives to coincide without hindrance. There is a group within The UM Church that would respond to such a voice. Given the heavily progressive leanings of the group’s leaders and interested persons, however, that may not be a fully accurate portrayal. The attempt to hold together mutually contradictory theologies may only result in an uneasy truce that invites a return to conflict in the not-too-distant future.

In the final analysis, the church will need to decide: do we perform same-sex weddings or not? Do we ordain practicing homosexuals or not? Will we welcome gay bishops or not? There is not a lot of middle ground in those decisions.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Nov 28, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2017

Founders of Knit-A-Prayer from left to right: Karen Wentzel, Sharon Wainwright, Rev. Dr. Richard Thompson, and Joyce Spetz. Photo courtesy of First United Methodist Church in Bakersfield, California.

By Katy Kiser-

Thousands of American service men and women have lost their lives in the on-going battle against terrorism. Since 2009, bodies of fallen soldiers, mostly from the war-torn areas of Afghanistan and Iraq, have been flown into Dover Air Force Base. At Dover, these heroes are given a dignified transfer as they are received by their grieving loved ones. And it is here that those loved ones are comforted by the ministry of the women of the First United Methodist Church in Bakersfield, California. The women call their ministry, Knit-A-Prayer.

The Dignified Transfer program at Dover has become a vital tradition of honor, respect, and a way of acknowledging the sacrifice of the fallen. Early in the Repatriation and Dignified Transfer program, chaplains at Dover asked for prayer shawls and lap blankets. They wanted grieving families to have something tangible to show that they were surrounded by the love of God and the prayers of fellow citizens. They also wanted them to know our country does not take their loved one’s loss of life for granted nor is it unaware of the deep grief the family experiences.

When families receive their fallen soldier at Dover Air Force Base, they are ushered onto the tarmac to witness a solemn ceremony as the casket is brought off a plane. Often the walk from the base to the plane is cold and windy. The shawls the family receives provide comfort both spiritually and physically. Many notes of appreciation have been sent to the Bakersfield women. For example:

“I’m writing to thank you on behalf of my sister. She and her family live in Arkansas. On November 20, her grandson, my great nephew, was killed in Afghanistan. When his dad flew to Dover AFB to receive his body, he was presented with a prayer shawl made by your group. Their hearts were touched by the shawl, the note you included, the words of comfort and the prayers that had gone up in the making of the shawl. I’m amazed at our God and how He works. Words cannot express our appreciation. God is good all the time. Blessings to you.”

Although the number of fatalities has fallen in recent years, the Methodist women in Bakersfield continue to pray and send the love of God to those who grieve.

In May, just before Mother’s Day 2017, Knit-A-Prayer celebrated its 10-year anniversary. It was founded by Sharon Wainwright, Joyce Spetz, and Karen Wetzel. When Sharon closed a needlework store she had operated for 22 years, she knew she must find something productive to do with her creativity and love of knitting. She mentioned this desire to her friends Joyce and Karen. Joyce knew about the prayer shawl ministry and ordered the book, Knitting Into Mystery: A Guide to the Prayer Shawl Ministry, which taught creating shawls as a way of nurturing one’s own and others’ souls through prayer. The three women met several times to pray and seek the Lord’s guidance before going to their pastor, the Rev. Richard Thompson, and receiving his blessing to start a ministry.

The three women were amazed at the interest in their proposed endeavor. Within a short period of time, 25 women signed up and committed to bi-monthly meetings. These women were intergenerational ranging from college-aged to mature women in their nineties. Over the last ten years, these women have sent 2,700 shawls and lap robes to people all over the world.

Sharon and her friends began by contacting another prayer ministry in their church known as Prayers and Squares, whose chapter #317 was started in 2005. This ministry, launched by Isabel Carrera, promotes prayer through the use of quilts. The quilters were happy to see their prayer ministry expand to a group who knitted and crocheted.

The quilting ministry originally began in San Diego at another United Methodist church, that sponsored an informal quilting group. A member’s two-year-old grandson, Kody, ended up in a coma following heart surgery; he had little chance for recovery. As the women worked quickly to make a quilt to cover this critically-ill child, they prayed earnestly for him. Against the odds, Kody came out of the coma. As he recovered, his little hands touched and fingered the knots on his quilt. His doctors wrote into his medical chart that the quilt was not to leave his side! The quilt remained with the child through several surgeries, tests, and treatments. It provided comfort and strength for many years. Other patients began to ask about the ministry and soon it had spread to other churches including Bakersfield First UM Church.

The process of making these quilts is saturated in prayer. When a quilt is requested, it is personalized to the recipient on a label and dated. As the women of the quilting ministry piece their quilts and tie in square knots the thread that holds the layers together, they pray for each recipient. After they finish a quilt, it is displayed so that the congregation may come and say a prayer while tying a knot on the quilt.

The same process is true for knitting and crocheting shawls. From the beginning of the project to its completion, the women bathe their work in prayer. Each shawl begins with a prayer for the recipient and their needs even when those needs are unknown. When they knit at home, they pray over their work. Some use a knitting pattern, a simple knit three, purl three that represents the Trinity.

One knitter shared, “In a sense this ministry is a ‘blind ministry.’ When knitting or crocheting a shawl one doesn’t know where it is going, what will be the effect, who will receive it, but God knows.” Another remarked, “There is joy in selecting the colors of yarn for the next shawl as well as the pattern. One can meditate while knitting. It is peaceful in God’s presence.”

Each shawl and blanket is bathed in prayer. Photo courtesy of First United Methodist Church in Bakersfield, California.

Opportunities to witness and share the love of Christ occur when a knitter has taken her project outside her home and works as she waits for an appointment or meeting. As one knitter explained, “Often an individual will strike up a conversation when they see someone knitting. That opens the door to talk about the prayer shawl ministry and our faith.” When the women gather together at the church, they take time to lay hands on their work and pray out loud in a ritual of prayer. At the completion of each shawl, a card is attached that includes a space for a hand-written prayer.

In their own city of Bakersfield, shawls are sent to several hospice groups and shelters for battered women, abused children, and the homeless. The women provide shawls and support for the Dream Center, a ministry to young adults in foster care who are required to transfer out of the program when they turn eighteen. At the center they are given help finding a permanent place to live, help with writing resumes, and learning how to interview for a job as well as other life skills.

The Knit-A-Prayer ministry steps into action when disasters of all kinds occur. In 2011, a 9.1 magnitude earthquake struck northeast of Tokyo; it was the largest ever to hit Japan. The resulting tsunami compounded the damage. Serving at the time were eight missionaries from the United Methodist General Board of Global Missions. The Bakersfield women sent their prayers and shawls to Japan, which were distributed by the missionaries along with other efforts by the United Methodist Committee On Relief (UMCOR).

GBGM contact, Claudia Genung-Yamamoto wrote, “These shawls have special meaning and we would like to distribute them through partner groups, especially through the Japanese church women with a message of God’s love shared with both Christian and non-Christians in the Tokyo area.”

Each package is a blessing to those who receive. Photo courtesy of First United Methodist Church in Bakersfield, California.

Closer to home, last summer these women sent shawls when one of California’s largest fires, the Erskine Fire, killed two people, destroyed 309 homes, and damaged hundreds more. People who lived in the path of the fire were in evacuation centers for weeks. These evacuees were not alone, for the Bakersfield women actively prayed and sent shawls through a long-time member of their church. He just happened to be serving as a local pastor for two of the communities hard hit by the fire.

The women share many stories where they have seen God’s hand on their ministry. One afternoon they received a request for a shawl from a lady in Missouri. She had found Knit-A-Prayer listed on a shawl ministry web site. She requested a shawl for a young adult man, seriously ill in San Diego. The shawl needed to be delivered quickly. Ironically, the daughter of the church’s administrative assistant was returning to San Diego that very afternoon. She took the shawl to the hospital and personally gave it to family members.

Another incident occurred when the women learned of a young girl who had attended VBS at the Bakersfield church. She was seriously ill with cancer. The mother was contacted and said she would appreciate a shawl for her daughter. When it was delivered, the little girl responded by saying, “How did you know that pink was my most favorite color?” She kept the shawl with her constantly through all her treatments until she passed.

Early in the spring of 2017, an adult nephew of a member of the Bakersfield congregation was seriously injured in an automobile accident. He was barely removed from the vehicle before it went up in flames. Doctors were unable to assure the family of his recovery. He was in ICU for a month and had many surgeries. Although he was not a believer in Christ, he kept the prayer lap robe with him constantly. All the prayers that were prayed for his recovery were eventually answered when he walked out of the hospital.

Prayers and Squares and Knit-A-Prayer are not ordinary clubs; they are not an excuse for women to get together for fellowship, although meaningful fellowship occurs; they are not just a creative outlet, although they are that as well. Prayers and Squares and Knit-A-Prayer are two groups of creative, praying Christian women, who like Jesus, are full of compassion; they are women who use their talent to make visible the love of God in the material blessing of a quilt or a shawl. Most of all, they are women who know the power of prayer to love, encourage, honor, heal, and comfort infinitely more than all they ask or imagine.

As Sharon Wainwright attests to the power of God working through the Knit-A-Prayer ministry, “God continues to open doors where we can offer a shawl and prayer. Our original hopes and dreams for this ministry were so small in comparison to where God has directed us. The ‘God winks’ have been many and the blessings numerous beyond measure.”

Katy Kiser is the team leader for the Renew Women’s Network. To learn more about these ministries, contact Isabel Carerra at thimble65@att.net, Sharon Wainwright at sew6439@aol.com or Renew Network at renew@goodnewsmag.org.

by Steve | Nov 28, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2017

The Rev. Kenneth Levingston of Jones Memorial United Methodist Church in Houston addressed the WCA event. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Sam Hodges-

The Rev. Kenneth Levingston used his pulpit time before the Wesleyan Covenant Association to compare The United Methodist Church to the valley of the dry bones, as described in Ezekiel. Tough talk, but Levingston held out hope.

“If God can move by his spirit, and make dead bones dance, then God can move by the same spirit and call a dead denomination to dance again!” thundered Levingston, pastor of Houston’s Jones Memorial United Methodist Church. “He can make it shake, rattle, and roll again!”

The Wesleyan Covenant Association’s third public gathering, held October 14 at The Woodlands United Methodist Church near Houston, offered lots of stirring preaching and no indication of what the evangelical group’s next move might be in trying to shape the denomination’s future. The Commission on a Way Forward is to issue an interim report to the Council of Bishops in November, suggesting possible structural changes that might allow the denomination to hold together despite deep divisions over how accepting to be of homosexuality.

So, Wesleyan Covenant Association leaders — who issued no statement at this gathering, though they did during their first — admit that in some ways they’re on hold. “We’re like the rest of the church right now,” said the Rev. Jeff Greenway, chair of the association leadership council. “We’re in a place of waiting to see what the commission is going to bring forward.”

The association’s leadership council met at length on October 13, but the association’s president said even that session was void of detailed strategizing. “Depending on what comes out, we will be ready for what unfolds, but we don’t have any specific plans that have been worked on and that are mapped out,” said the Rev. Keith Boyette, the association’s president.

The association formed last year as an organization of United Methodist clergy, laity, and churches committed to what it describes as an orthodox understanding of Wesleyan Christian faith. Unlike some other advocacy groups within the church, it charges membership dues.

The group also holds that marriage should be for “the uniting of one man and one woman in a single, exclusive union,” and has complained that Bishop Karen Oliveto, who is married to another woman, continues to serve despite church law restrictions against gay clergy.

Since its organization after the 2016 General Conference, the association has grown to 2,500 individual, dues-paying members, and about 200 membership churches, representing some 100,000 United Methodists around the world, Boyette said. The meeting at The Woodlands United Methodist attracted a few hundred people, but Boyette said simulcasts to 64 U.S. sites brought total attendance to about 2,300. He added that the association would continue to use technology to reach local churches.

At the October 14 gathering, association leaders introduced a book, A Firm Foundation: Hope and Vision for a New Methodist Future, and an app as resources for small groups. “We want to empower people at the local church level,” Boyette said. “We want (the association) to grow from the bottom up.”

The association also welcomed to its leadership council the first international members, from Africa and the Philippines. One of them, the Rev. Forbes Matonga of Zimbabwe, preached at the gathering.

The Rev. Jerry Kulah of Liberia, another new council member, praised the theological focus of the association and leaders’ embrace of global perspectives. “Africans do not want to be accommodated,” Kulah said in an interview. “Africans want to be part of the solution.”

Among the gathering’s preachers was retired Bishop Robert Hayes Jr., now bishop-in-residence at The Woodlands church. Texas Conference Bishop Scott Jones attended, but did not speak. “My role as bishop is to remain connected to as many different groups as possible, to help improve the quality of conversation about the future of our denomination,” Jones said.

Jennifer Cowart addresses the WCA event in Houston. Photo by Steve Beard.

The day was dominated by preaching, with speaker after speaker calling for a return to an evangelistic focus. “People need to take an unapologetic stand for Christ, for biblical standards, always erring on the side of grace and love,” said Jennifer Cowart, executive pastor of Harvest Church, a United Methodist congregation in Warner Robins, Georgia.

The Rev. Shane Bishop, pastor of Christ (United Methodist) Church in Fairview Heights, Illinois, noted the long decline of membership and attendance in The United Methodist Church in the United States, as well as internal divisions. “I know there’s a lot of denominational uncertainty right now,” he said. “But there’s not one thing happening in The United Methodist Church that can keep you and me from telling people about Jesus Christ.”

Without specific reference to the status of LGBTQ people in the church, speakers emphasized the authority of the Bible over the values of contemporary culture.

The Rev. Rob Renfroe, pastor of discipleship at The Woodlands United Methodist and president of the unofficial evangelical advocacy group Good News, said United Methodists should worry about being “on the right side of eternity” rather than the right side of history.

Greenway described the gathering as “a family reunion for folks who are like-minded and warm-hearted by Jesus in the orthodox Wesleyan tradition.” But the question about how or whether The United Methodist Church can avoid splitting was always in the background, and sometimes came to the fore.

Boyette noted in his remarks the recent formation of two more groups, the “Uniting Methodists” and the “United Methodist Association of Retired Clergy.” Both seek to influence the debate leading up to a special General Conference in 2019. And that’s fine, Boyette asserted. “These are people of good will that have different visions for the church,” he said in an interview. “It helps the church to really have clarity in what we’re facing.”

Sam Hodges, a United Methodist News Service writer, lives in Dallas.

By David Watson-

By David Watson-

By Scott Jones-

By Scott Jones- By Thomas Lambrecht-

By Thomas Lambrecht-