by Steve | May 27, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May-June 2021

Thomas Lambrecht

By Thomas Lambrecht –

The dust is clearing after an eventful last few months for The United Methodist Church. General Conference is postponed in-person to August 2022. A special virtual General Conference was scheduled for May 8, 2021, and then canceled.

The new Global Methodist Church has been unveiled as denomination information – to be formally inaugurated following the anticipated enactment of the Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace through Separation at an upcoming General Conference.

The desire to hold a virtual General Conference in May demonstrated how “stuck” the church currently is. The Commission on the General Conference concluded it could not hold a General Conference virtually because it would rule out equitable participation by all delegates around the world, particularly in Africa and the Philippines. Yet, the Council of Bishops felt the need to call a virtual General Conference despite that anticipated inequity.

The Judicial Council had to formulate church law (not their responsibility) in order to save the administrative process allowing the church to deal with ineffective clergy and clergy unable to fulfill their duties, after the Council had ruled that process unconstitutional. Bishops that are required to retire under the Book of Discipline cannot retire because their jurisdictional or central conference cannot meet. General, jurisdictional, and central conferences are not empowered to meet virtually in extraordinary circumstances. There is no way to change the quadrennial budget if the General Conference cannot meet to do so.

Therefore, the church continues to operate under the 2017-2020 budget, which is obsolete. Certain annual conference officers cannot be elected until after the General Conference meets. These and other decisions await the opportunity for General Conference to meet, and they show how the church is “stuck” in the meantime.

What about the Protocol for Separation? The Council of Bishops’ agenda for the special virtual General Conference did not include the Protocol. Yet the biggest obstacle to getting the church “unstuck” is the decision about moving forward with separation. If the General Conference approves of separation, then conferences and churches can move forward with their decision about how they want to align themselves. If the General Conference does not approve of separation, then the church would return to the state of elevated conflict seen during and after General Conference 2019.

Acting on administrative matters, but not the Protocol, might get the church “unstuck” administratively, but it would not get the church “unstuck” in the larger sense. We would continue to live in uncertainty, unable to effectively invest in expanded ministry and unsure of our future identity. This is not healthy.

It would be far better to deal with the big decision on separation early, so that all the other decisions to be made in the future could flow from that one.

- What should the budget be for the current quadrennium and into the years beyond? That depends upon whether separation occurs and how many churches and members align with a new denomination.

- How many bishops should we elect in 2022 (or whenever episcopal elections become possible)? That depends upon how many annual conferences remain in The United Methodist Church and what their financial capacity is.

- Should we elect five new bishops in Africa, as promised in 2016? That depends on how many African annual conferences remain in the UM Church or go with the Global Methodist Church, and what is the financial capacity of the UM Church after separation.

- What will be the annual conference boundaries? That depends upon how many local churches remain in each region. Annual conference boundaries will likely need to be redrawn in some cases by the jurisdictional or central conferences when they are able to meet.

- How many general church boards and agencies do we need and how should they be structured? That depends upon how many people remain in the UM Church and the financial capacity of the remaining denomination.

- How many seminaries can the UM Church sustain? That depends upon how many students are likely to go into ministry in the church and how many churches remain as potential places to serve.

These and many other decisions flow from the one big decision about separation. The Council of Bishops envisioned at least some of these decisions taking place in virtual jurisdictional and central conference meetings later in 2021, which now may not be possible. But those decisions would be shots in the dark if we have not decided about separation.

As the Council of Bishops engages in “deep listening” – their phrase – and attempts to discern “a new timeline” leading up to the next General Conference, they should formulate a way for the General Conference delegates to consider and act upon the Protocol at the earliest possible time.

An Emerging Concern. I have concerns about the viability of an August 2022 in-person General Conference. Current vaccination information coming out of Africa is that some parts of the continent will be less than half vaccinated by the middle of 2023! Unless the pace of supply and distribution of vaccines picks up dramatically, it will not be possible for African delegates to travel to the U.S. for a 2022 General Conference. Under that scenario, an in-person General Conference may not be possible until the scheduled conference in May 2024.

For the church to remain “stuck” for the next three years would present an untenable situation that would contribute to the further precipitous decline of the church in the U.S. and other areas. The longer the delay in acting on the Protocol, the more opportunities for bishops and cabinets to marginalize evangelical and traditionalist clergy and congregations in their annual conferences. We have had several reports that local pastors were discontinued by their district committee on ordained ministry because those local pastors were honest about their intention to align with the Global Methodist Church when such alignment is possible. We have had reports of local churches being closed when they inquired of their district superintendent how much they would have to pay if they decided to withdraw from the church prior to the Protocol passing.

The tenuous truce that currently exists, where no complaints are filed against partnered gay clergy or clergy who perform same-sex weddings, may be jeopardized by zealous progressive proponents victimizing traditionalist clergy and congregations. The longer we put off separating, the more likely the truce will unravel. The original moratorium proposed in the Protocol against the processing of complaints regarding LGBT clergy and weddings was only supposed to last five months until the Protocol was enacted. (Once it is enacted, there is no reason for traditionalists to file complaints, since they will be embarking to a new denomination.) But a five-month truce that turns into four years becomes a much more unstable situation that could jeopardize the spirit of calm that has characterized the past year of the church conflict.

It is up to the Council of Bishops and the Commission on the General Conference to begin planning now for the potential further postponement of General Conference beyond 2022 and setting in place the means for having a virtual General Conference that could address the Protocol.

What about Amendments to the Protocol? With a virtual General Conference, it is possible that there could be limited or no amendments to the Protocol and limited debate on the floor of General Conference. Given that the Protocol has been published and discussed publicly for over a year, it seems that the delegates ought to be familiar with its provisions. Additional communications could be prepared by the Protocol mediation group to further inform delegates of its provisions. A website has been available for over a year, with the Protocol agreement, the proposed legislation, frequently asked questions, and a PowerPoint presentation. They are available in all the official church languages. The resources are there to communicate the provisions of the plan.

There are some who would like to make changes to the provisions of the Protocol. If enough delegates want to entertain amendments, the Commission on General Conference could work out a way to do so. Alternatively, the delegates could decide to postpone action on the Protocol until an in-person General Conference becomes possible, even if it has to wait until 2024. However, the advantages of making the big decision on separation now in order to set the table for all the other following decisions outweighs any advantage that might be gained by the uncertainty of adopting amendments at a future date. Those proposed changes might not pass, and then we would have waited months or years for nothing. The grassroots laity in our church already believes this decision has been postponed far too long. Waiting will only reinforce that perception, no matter the good motives of those who want to postpone it.

Furthermore, the terms of the Protocol were negotiated in very rigorous and conflictual discussions. Each term was the result of a careful compromise between various viewpoints. For a majority of the delegates to change even one of the terms of the Protocol could jeopardize support for the whole package. While no one at the table thought the Protocol was perfect according to their perspective, all agreed that it is the best way to resolve our conflict and allow the church to get “unstuck.”

What about the Money? Some are concerned that the church might not be able to afford the provision that shares $25 million with a new traditionalist denomination and $2 million with other denominations that might form. While the apportionment income to the general church understandably fell in 2020, the financial provision was negotiated based on the church’s unrestricted reserve funds, not annual apportionments. While we do not yet know what amount remained in the church’s reserve at the end of 2020, the reserve was actually higher at the end of 2019 than when the Protocol was negotiated. We know that many of the boards and agencies received hundreds of thousands of dollars in PPP grants from the U.S. government in 2020. We also know that many of the boards and agencies have cut their staffs in order to adjust to lower expected apportionments in the years ahead.

The $27 million allocated to new denominations is not a “gift” from the UM Church to the new churches, but represents a proportional sharing of accumulated resources that were given by faithful United Methodists over the decades who will now serve the Lord in a different Methodist denomination. The money would be paid over four years, lessening the burden in any particular year. Its primary purpose would be to extend the church’s mission of making disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world in new Methodist expressions.

There are no compelling reasons at this time to change the financial provisions of the Protocol. And the ability to get the church “unstuck” and moving forward outweighs any potential benefit from having a fight about money on the General Conference floor.

Advantages for Centrists and Progressives. Many centrists and progressives have expressed frustration at their inability to move forward with their agenda for the church. Making the big decision on separation now would enable them to have a majority of the delegates to enact their program at the next in-person General Conference. If the Protocol is not enacted until 2022 or later, they may not be able to make the changes they desire until the 2024 General Conference or potentially even in 2028 (if the Protocol is not enacted until 2024).

Due to the moratorium requested in the Protocol, some annual conferences are currently ordaining practicing gays and lesbians to ministry and allowing same-sex weddings in local churches. However, other annual conferences are not doing so. Passing the Protocol now and subsequently removing restrictions from the Discipline would allow such ordination and weddings in all annual conferences that remain in The United Methodist Church.

Proponents of the Christmas Covenant and the Connectional Table regionalization plan hope to pass changes that would enable each geographic region of the church to govern its affairs in a more semi-autonomous fashion. Because those proposals need a two-thirds vote to pass, it is unlikely they would pass while traditionalists remain in the church. Passing the Protocol now would enable the next in-person General Conference to pass the regionalization plans and secure ratification, so they could be implemented more expeditiously.

Passing the Protocol would allow the centrist and progressive agendas for the church to move forward much more quickly than waiting until the next in-person General Conference. It would also allow the new denominations to form immediately and move forward in the new directions they envision. Most importantly, it would definitively end the theological conflict that is causing the UM Church to be “stuck.” The resulting churches would be truly “unstuck” and empowered to pursue ministry as they feel called by God.

Passing the Protocol is the only way to avoid protracted and expensive litigation, ensure that unfunded pension liabilities will be addressed, and enable the church to move beyond decades of conflict. Our church would be an example to a conflicted world that it is possible to settle disputes amicably and without winners and losers. Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers.” The Protocol is the way to peace in The United Methodist Church.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | May 26, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May-June 2021

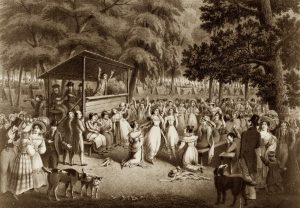

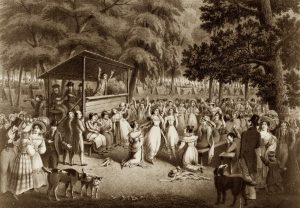

A lithograph, of unknown origin or date, illustrates a camp meeting popular in the early 1800s.

By Windfield Bevins –

Methodism swept across the American frontier like an uncontrollable prairie fire. That is hardly how we would describe it today. There are great benefits in considering some of the things that led the decline of Methodism.

What lessons can we learn from the past so we don’t repeat them tomorrow?The first warning we can take from the Wesleyan revival is to observe what can happen to any movement over time. Sadly, some movements, as they become institutionalized, also grow more secular, losing the “evangelical” focus that gave them life in the first place. Many denominations that began as transformative movements eventually became institutionalized, leaving behind their original roots. If the cultural values and beliefs that initially helped the movement grow are not passed down to succeeding generations, this institutionalization will lead to the loss of the gospel focus and of disciple-making.

C.S. Lewis warned against this, saying, “There exists in every church something that sooner or later works against the very purpose for which it came into existence. So we must strive very hard, by the grace of God to keep the church focused on the mission that Christ originally gave it.” The cure for this secularization of the revival spirit, as Lewis suggests, is to develop habits and practices that keep us faithful to the original mission of the church: the call to preach the gospel and make disciples.

We see this pattern repeated throughout history. Many of the great revivals of the past began as Spirit-inspired disciple-making movements, yet over time they became secular institutions. For example, consider the history of the modern university.

Many colleges, including state universities in the United States, started out as Christian institutions to train young people for ministry and Christian service. Schools like Harvard (Puritan), William and Mary (Anglican), Yale (Congregational), and Princeton (Presbyterian) were created for Christian higher education. The Great Awakening led to the founding of Princeton, Brown, Rutgers, and Dartmouth in the mid-eighteenth century, and to the single most prolific period of college founding in American history. Over time, however, the revival spirit that founded these institutions was lost, and most of these former Christian colleges and universities became secular universities with little or no religious affiliation.

Institutionalization. Methodism was one of the greatest and longest-lasting discipleship movements in the history of the church. Yet as Methodism continued to grow, Wesley noticed that the movement was following the patterns of institutionalization. He lamented that this was happening, and he felt that a grim fate might befall the Methodists if they ever lost their zeal.

“I am not afraid that the people called Methodists should ever cease to exist either in Europe or America,” Wesley wrote. “But I am afraid, lest they should only exist as a dead sect, having the form of religion without the power. And this undoubtedly will be the case, unless they hold fast the doctrine, spirit, and discipline with which they first set out.”

Sadly, this is exactly what happened to Methodism in the United States. Just one hundred years after the miraculous growth of the movement, there were warning signs of secularization. Today, the United Methodist Church, the descendant of the American Methodist movement, is in rapid decline and on the verge of splitting into factions. What caused this shift, making a large and growing denomination one of the fastest declining?

History teaches us that the church is susceptible to the secularizing tendencies of institutionalization whenever it loses focus on the message and mission of Christ. In The Convergent Church: Missional Worshipers in an Emerging Culture, Alvin Reid and Mark Liederbach observe, “When the church loses, forgets, or fails to emphasize the missional thrust of its purpose … it is a move away from a movement mentality toward what we would describe as institutionalism.”

Whenever movements are transformed into institutional churches, they will begin to reduce the tension they feel with respect to the surrounding culture. There is less emphasis placed on growth and multiplication, and this leads to a loss of growth and the start of a slow decline. This pattern has repeated over and over again throughout the history of the church. And while there are many sociological factors to consider, there are three primary reasons this secularization occurred in the Methodist movement, leading to its decline in North America.

Shift in Preaching. As Methodism became an established church in North America, there was a strong impulse to “keep up” with the more established churches and to become a respectable part of society. Though the movement had grown and multiplied through lay preachers and circuit riders, the days of the traveling preacher on horseback were now replaced by fancy pulpits and robes. According to Methodist historian William Warren Sweet,

“Clergy culture and learning were no longer a monopoly of the Congregationalists, the Presbyterians, and the Episcopalians. Education, refinement, and dignity now characterized the ministry and service of the Methodists.”

This resulted in a shift in the preaching. Clergy moved away from simple messages on sin and salvation to speak about science and politics. Gone were the days of the Methodist camp meeting. Early Methodist preachers had arisen from among the common people, speaking the language of the ordinary man. A generation later, pulpits were filled with clergy who geared their message to a more educated, socially conscious audience.

Over time the pioneering, counter-cultural spirit of the Methodist movement was domesticated. With the rise of educated clergy and increased social status came a further shift away from the original emphasis on holiness and the “methods” of the class meeting. As sociologists Roger Finke and Rodney Stark note, “Their clergy were increasingly willing to condone the pleasures of this world and to de-emphasize sin, hellfire, and damnation; this lenience struck highly responsive cords in an increasingly affluent, influential, and privileged membership. This is, of course, the fundamental dynamic by which sects are transformed into churches, thereby losing the vigor and the high-octane faith that caused them to succeed in the first place.”

Focus on Buildings. One hundred years from its humble beginnings, Methodism in North America had finally arrived. Not only had the Methodists become the largest denomination in the land, they had moved up the social ladder of society and were beginning to attract people of wealth and privilege. They had shifted from meeting in simple, unadorned buildings to constructing large, expensive facilities that rivaled the nicest established church buildings in town. In 1911, a new building for a Methodist congregation in Illinois even began charging $200 for good seats at the church.

These new, fancy buildings were a visible sign that Methodism had moved away from the vision of its founder. Once an upstart sect, it had become one of the established religions of the young nation. Yet while some would see these as positive signs, they were the beginning of the end of the Methodist movement in North America.

Today, you can look at almost any town in North America and find an impressive Methodist church building from this era, yet sadly, most of these have closed or are in the process of closing their doors due to declining membership.

Cutting the Class Meeting. The final nail in the coffin was the demise of the class meeting. From the time of the founding of Methodism, to be called a Methodist meant that you were a member of a class meeting. Yet over time this requirement was lost, and many began to see it as a sign that the movement had begun to falter. In 1856, at the age of seventy-two and in the fifty-third year of his ministry, the famous Methodist circuit rider preacher Peter Cartwright was already lamenting the loss of the class meeting:

“Class meetings have been owned and blessed of God in the Methodist Episcopal Church … For many years we kept them with closed doors, and suffered none to remain in class meeting more than twice or thrice unless they signified a desire to join the Church … Here the hard heart has been tendered, the cold heart warmed with the holy fire; But how sadly are the class meetings neglected in the Methodist Episcopal Church! … Is it any wonder that so many of our members grow cold and careless in religion, and finally backslide? … And now, before God, are not many of our preachers at fault in this matter?”

Reading Cartwright’s words, one can sense the grief of a man who had experienced the exciting energy of the Methodist revival and was now seeing that movement sliding toward institutionalization and into decline.

On my desk is a framed class meeting ticket from 1842 that belonged to a woman named Maria Snyder. Looking at it today, I can’t help but wonder, “What would Maria think of contemporary Methodism?” or “What would John Wesley or Francis Asbury think about the current state of the movement they started?”

Across the Western world, thousands of churches are closing every year. When will we feel grief over the state of our churches? Will a new generation once again heed the call to recover Scriptural Christianity? Might we see another disciple-making revolution spread across our country and around the world?

Winfield Bevins is the director of church planting at Asbury Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. Over the years he has served as a pastor, professor, and church planter. Some of this content is from WinfieldBevins.com, Marks of a Movement: What the Church Today can Learn from the Wesleyan Revival (Zondervan, 2019).

by Steve | May 26, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May-June 2021

Terry Mattingly

By Terry Mattingly –

While working on the 1985 book Habits of the Heart, the late sociologist Robert N. Bellah met “Sheila,” who described her faith in words that researchers have quoted ever since.

“I can’t remember the last time I went to church,” she said. “My faith has carried me a long way. It’s Sheilaism. Just my own little voice.” The goal was to “love yourself and be gentle with yourself. … I think God would want us to take care of each other.”

A decade later, during the so-called “New Age” era, researchers described a similar faith approach with this mantra – “spiritual but not religious.” Then in the 21st Century’s first decade, the Pew Research Center began charting a surge of religiously unaffiliated Americans, describing this cohort in a 2012 report with this newsy label – “nones.”

Do the math. “Nones” were 10 percent of America’s population in 1996, 15 percent in 2006, 20 percent in 2014, and 26 percent in 2019. Obviously, these evolving labels described a growing phenomenon in public and private life, said political scientist Ryan Burge of Eastern Illinois University, author of the new book, The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are going. But hidden under that “nones” umbrella are divisions that deserve attention. For example, the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study found that 5.7 percent of the American population is atheist, 5.7 percent agnostic, and 19.9 percent “nothing in particular.”

“When you say ‘nones’ and all you think about is atheists and agnostics, then you’re not seeing the big picture,” said Burge. “Atheists have a community. Atheists have a belief system. They are highly active when it comes to politics and public institutions. But these ‘nothing in particular’ Americans don’t have any of that. They’re struggling. They’re disconnected from American life in so many ways.”

In his book, Burge stressed that “nothing in particulars are one of the most educationally and economically disadvantaged groups in the United States today.” This is also a growing slice of the population, with one in 20 Americans becoming “NIPs” during the past decade. While Protestants, at 40 percent, are the largest flock in American religion, the “nothing in particular” crowd is the second largest, at nearly 20 percent. Catholics are close behind at 18 percent.

Several other trends have affected the “nones” phenomenon, noted Burge. For example: Christians who say they never go to church increased from 10 percent in 1993 to above 15 percent in 2018. Meanwhile, America’s liberal “mainline” Protestant churches were 30.8 percent of the population in 1976 – but crashed to 19 percent in 1988 and down to 9.9 percent in 2016. Evangelical Protestants have remained relatively stable at about 21 percent, declining from a peak from 1983-2000. Catholics have varied between 27 and 23 percent, with mass attendance declining.

Most academics, politicos, journalists and even Christian apologists have, when addressing “nones” issues, focused on the most visible forms of this phenomenon, said Burge. It’s easy to find and quote articulate, highly motivated atheists and agnostics in online forums or “woke” secular activists on college and university campuses.

But “nothing in particular” Americans have remained in the shadows and it’s hard to find clear patterns that might explain their beliefs and behaviors. For example, not all “nothing in particular” Americans are unbelievers, strictly defined. One in 10 “NIPs” attend worship services yearly and another 10 percent attend monthly or more. And 25 percent of these Americans say that religion is “somewhat” or “very” important, with only 38.8 percent insisting that religion is “not at all important” in their lives.

“Nothing in particular Americans seem to be stuck. They’re left out. They’re cut off and trapped by globalization and economic forces that are totally beyond their control,” said Burge. “Many are angry, and they have nothing to lose. That’s why this NIP phenomenon is kind of scary to me.”

Terry Mattingly (tmatt.net) leads GetReligion.org and lives in Oak Ridge, Tenn. He is a senior fellow at the Overby Center at the University of Mississippi.

by Steve | May 26, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May-June 2021, May/June MJ 2021

Jenifer Jones

By Jennifer Jones –

I almost didn’t go on the “GreenLight” mission trip. I had already participated in a fair number of short-term mission trips and had already visited the country where the team would be going. I was concerned whether the experience would bring me closer to solving the puzzle of what to do with my life – where God was leading me.

At 10 years old, I felt a call to missions after hearing missionaries speak at my church. I felt certain that I would go to college to become a teacher, marry a pastor, and head overseas. This was what I thought you had to do to become a missionary.

Then, just before graduating high school, I felt God saying “no” to missions. I was confused and angry. Had I not heard God’s voice after all? Why would he give me a desire to serve him overseas and not let me go?

I’ve always loved to write, so instead of going to school to become a teacher, I studied to become a journalist. After graduation, I got a job at a fantastic radio station. When it looked like there might be cuts at my workplace, I began looking for other options.

I felt God calling me to a year-long mission trip. “This is it!” I thought. “God is finally letting me go!” I figured I would fall in love with a country, feel the call to move there full-time, and I would be all set. That didn’t happen. But I realized I loved writing about what God was doing and my time as a journalist hadn’t been for nothing after all.

Once back in the United States, I began looking into organizations hiring missionary writers. Nothing felt quite right. A friend suggested I look into Asbury Theological Seminary, and I felt like it was what God wanted me to do. That’s where I was introduced to TMS Global and learned about its “GreenLight” missions trip – a short-term mentorship experience. My teammates and I spent three weeks learning from four cross-cultural

Workers (missionaries) and their children as they interacted with their community, their friends, their employees, and their family.

For parts of the experience, I questioned whether I was called to missions. For example, the needs of the people around us felt very overwhelming. I also questioned my skills. It didn’t always feel like I had much to contribute.

But on one of our last days, our hosts spent time noting positive things they had seen in myself and the other participants. These cross-cultural workers reminded me that just spending time with others could be a powerful contribution. They also affirmed my calling as a missions writer. Ultimately, I realized I did not feel a sense that I was meant to live full-time overseas, at least not right now.

Over the next couple of years, as I finished seminary, a mobilizer with TMS Global continued to work with me to further discern whether it was the right mission organization for me, and if so, what that might look like. She listened as I shared my hopes, goals, dreams, and desires. I could tell that she really cared about me, and not just about filling a spot in the organization. I wanted to tell missions stories. But I also wanted to live closer to my family. My new work at TMS Global incorporates multiple dreams that God had laid on my heart. It is a perfect fit for me.

The road to get where I am now has been long and winding, but I’m able to see how God has worked the various parts of my life and experiences together to prepare me for my current place. So much of my discernment process has been gradual. It has involved paying attention to my passions and talents, circumstances, life experiences, and wisdom from trusted sources. I’m grateful for the people who have guided me. I’m also thankful for experiences like the GreenLight trip that have helped me discern a place in God’s mission just right for me.

Jenifer Jones is a writer who focuses on telling stories about the work God is doing in the world. She’s also a poet. Find her writing at www.jeniferjones.com. If you are interested in someone walking alongside you in your discernment experience, reach out to TMS Global today at go@tms-global.org.