by Steve | Sep 15, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Perspective E-Newsletter

Bishop Sharma Lewis

By Bishop Sharma Lewis-

Brothers & Sisters:

As we continue to process the disturbing events from Charlottesville, Virginia, we need to turn to God for understanding, guidance, and strength in our next steps.

As Christians and United Methodists, we are to act. Hatred of any kind, including racism, is intolerable. As faithful people, we are commanded to address it by being witnesses and advocates for the marginalized.

Racism remains in the world. While progress has been made, particularly since the days of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., we must eliminate racism and not stop until it is fully and irrevocably gone. As such, I ask that you do the following.

Pray. Let us pray for the families of Heather Heyer, Lt. H. Jay Cullen, and Trooper Berke M.M. Bates. Let us pray for the injured, especially those still hospitalized. Whether we come together for prayer vigils or rallies, for Charlottesville, the Commonwealth, and even our country, let the foundation of these be rooted in love and concern.

Witness. We need to stand together as the people of God and have our voices heard. Our witness is lost when we as Christians do not stand up and advocate, especially in times like this.

We need to denounce white supremacy, neo-Nazis, and the KKK. No race is superior to any other; as Christians we know that all persons are created equal in the image of God.

Our baptismal vows remind us “to renounce the spiritual forces of wickedness, reject the evil powers of this world, and repent of your sin. Do you accept the freedom and power God gives you to resist evil, injustice, and oppression in whatever forms they present themselves?”

Preach. Many pastors have already been addressing the events in Charlottesville. We must continue to prophetically speak the truth and address the sin of racism. In our teaching and preaching, we must not browbeat, but rather show the light of Christ.

Combating Racism. While our physical presence is important to our roles as witnesses and advocates at rallies, we have work to do beyond these rallies in our Conference and in our local churches.

I have found in my ministry that racism is rooted in ignorance. In addressing racism, we must be intentional in getting to know our brothers and sisters and address the sin of racism, hate, and violence. This is important work for our local churches.

In the days ahead, we know that God, love, peace, and prayer will overcome all of this hatred and fear. We must be vigilant in our witness and peaceful in our advocacy.

I pray for you and our nation as we seek to do this hard work ahead. Peace and Blessings,

Sharma Lewis is the United Methodist episcopal leader of the Virginia Annual Conference. Reprinted by permission.

by Steve | Sep 15, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2017

Baroness Caroline Cox

By Jeff Walton-

More than 250 million Christians are suffering persecution of some kind around the world today, according to Baroness Caroline Cox, founder of the U.K.-based Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust (HART). Many live under the oppression of Communism, fundamentalist Hinduism, political Buddhism, and, above all, militant Islam.

Cox, a member of the British House of Lords and former Deputy Speaker, spoke June 30 before 1,400 clergy, bishops, and lay delegates at the Provincial Assembly of the Anglican Church in North America held on the campus of Wheaton College in Illinois. Quoting Saint Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians, Cox said, “When one part of the Body of Christ suffers, we all suffer.” She continued, “We do have a mandate to be alongside those brothers and sisters… If not necessarily in person, then certainly in spirit and prayer.”

Cox relayed the words of a woman whose child was dying of starvation in Sudan: “I could go to a government-held area, get some food and medicine, and save my little boy, but I am a Christian. I’m not going to convert to Islam. We will live and die as Christians.” Cox assessed: “To sacrifice yourself must be tough. To sacrifice your child – I am blessed with 10 grandchildren – I can hardly imagine sacrificing a child for my faith. That is the price of faith for so many of our brothers and sisters.”

Speaking of Nigeria, Cox reported that over recent decades, thousands of Christians have been killed and hundreds of churches burnt. Many Muslims have also died at the hands of Boko Haram. “The escalation of Boko Haram’s brazenness is creating a reign of terror and intimidation in northern Nigeria,” Cox explained. Showing footage of devastated church buildings, she described the Boko Haram tactic of suicide bombers driving explosive-laden vehicles into the middle of church services. “But even there, in the middle of that destitution – of that horrendous destruction – people still praise God,” Cox reported, showing the words “To God be the Glory” etched on the wall of a destroyed church building. “The very stones cry out under persecution, but they cry out with worship,” Cox said. “We never hear a message of revenge, hate, or bitterness.”

Quoting Archbishop Benjamin Kwashi of Jos, Nigeria, Cox read: “If we have a faith worth living for, it is a faith worth dying for. Don’t you compromise the faith that we are living and dying for.”

In another presentation at the event, Bishop Grant LeMarquand of the Horn of Africa spoke alongside his wife Wendy about their ministry among refugees in Gambella, Ethiopia, near the border of South Sudan. Addressing the “global crisis” of 65 million refugees, the LeMarquands told of 350,000 refugees from South Sudan in their own area and the losses they had experienced.

“Bullets came, we ran, we carried only our children,” Dr. Wendy LeMarquand relayed of a story from one group of refugees that arrived from South Sudan. While they had no food or clothes, the refugees were most sad about losing their elderly. “The blood of Abel cries for vengeance, the blood of Jesus cries for forgiveness,” Bishop LeMarquand explained of the unique message the Gospel brought to people hurting amidst ethnic strife.

Jeff Walton is Communications Manager for the Institute on Religion & Democracy and staffer on the Anglican Action program. Reprinted by permission.

![Is There a Way Forward?]()

by Steve | Sep 15, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2017

By Walter Fenton-

By Walter Fenton-

For nearly nine months now the Commission on a Way Forward has been meeting behind closed doors in an attempt to fulfill two almost impossible tasks: producing a plan to definitively resolve the deep disagreement over The United Methodist Church’s sexual ethics and maintain some semblance of church unity.

The idea of a commission was proposed and approved at the May 2016 General Conference in an effort to avoid chaos. The church’s highest administrative body, the Connectional Table, had come to the quadrennial gathering with a plan to liberalize the church’s teachings on marriage and to allow annual conferences to decide whether to ordain openly gay clergy. However, it quickly became apparent that even though the plan had significant support it would still be defeated, just as all previous attempts to change the church’s teachings had been rejected at previous General Conferences.

The Council of Bishops (COB) knew another vote rebuffing efforts to liberalize the church’s teachings would ignite waves of protest by allies of the LGBTQ+ movement. Some feared the conference would spin out of control and prove to be a public relations disaster for the UM Church. The Commission on the General Conference had contracted for heightened security and police presence at the Portland, Oregon Convention Center. All delegates and visitors had to pass through security checkpoints, and for the first several days of the conference the Portland Police Department maintained a pronounced presence in and around the convention center.

Given the dynamics of the situation, the COB seized on a proposal to table all legislation having to do with the church’s sexual ethics and teachings on marriage, and in turn create a commission to study the controversy and propose a definitive plan for resolving the long debate. The proposal narrowly passed 428 to 405. It gave the COB the authority to select the commission members and to convene an unprecedented called General Conference to consider a forthcoming proposal.

While the maneuver averted chaos at the General Conference, it did not cool passions at the annual and jurisdictional conference levels in the U.S. Within weeks of General Conference, several annual conferences voted to defy church law when it came to examining clergy candidates for commissioning and ordaining. Bishop Jane Middleton, on the recommendation of the New York Annual Conference’s Board of Ordained Ministry, ordained and commissioned openly gay candidates.

Matters took a turn for the worse when the five U.S. jurisdictional conferences convened in July. Delegates at the Northeastern Jurisdictional Conference in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, passed several measures calling for ecclesial disobedience regarding the church’s sexual ethics and ordination standards. And then, on July 15, 2016, in Scottsdale, Arizona, the Western Jurisdiction elected as a bishop of the whole church, the Rev. Karen Oliveto, an openly lesbian pastor. It was widely known at the time of her election, consecration, and assignment that Oliveto had presided at dozens of same-sex marriages, and was herself married to Ms. Robin Ridenour, a United Methodist deaconess. The votes for defiance of church law and Oliveto’s election jolted the denomination.

Initially, many United Methodists, bishops included, believed these developments plunged the church into a crisis and warranted standing-up the commission as quickly as possible. However, it took the COB five months to announce the names of the 32 commission members and its three episcopal moderators. Before the year was over, the commission had met just once for an introductory conference call, and original plans for a called General Conference in 2018 were eventually pushed back to February 23-26, 2019, to be held in St. Louis.

In the meantime the church continues to confront growing challenges. Acts of ecclesial defiance have continued. Two large and growing conservative churches in Mississippi have left the denomination with all their property and assets, and other local churches are exploring their options. Several annual conferences are experiencing severe financial strains, with one characterizing its situation as a “crisis.” Some rank-and-file United Methodists have curtailed their giving, or requested that no portion of their tithes and gifts be forwarded to the annual conference or general church. And some local churches have decided to withhold their apportionments entirely.

Since the beginning of 2017, the commission has met four times, twice in Atlanta, once in Washington D.C., and recently in Chicago. The church is slated to spend $1.5 million on the commission, and another $4 million for the called 2019 General Conference. It is no exaggeration to say the fate of the denomination hinges on the plan the commission submits to the COB, and that it in turn presents to the delegates in St. Louis.

My Good News colleague, the Rev. Thomas Lambrecht, serves on the commission that has been meeting behind closed doors and has pledged itself to not divulging information of their proceedings. This article is based on several plans that had been floated prior to the creation of the Commission as well as the public comments made by Commission members and others that characterize their discussion of “simpler” and “looser” connections, as well as “new forms and structures.”

What follows is a portrayal of the groups involved in the debate, and descriptions and critiques of some potential plans the commission may propose.

Reconcilers, Liberalizers, Conservatives

One group might best be called reconcilers. For the sake of church unity reconcilers can live in a church where others think and act differently about the church’s sexual ethics, same-sex marriage, and ordination standards.

They could make room for pastors who could not, in good conscience, preside at same-sex weddings and for pastors who would joyfully preside at them. And if an annual conference voted to ordain openly gay clergy, reconcilers would welcome them just as long as other annual conferences were free to maintain the UM Church’s current position forbidding such ordinations.

Even more fundamentally, reconcilers would make room for people who believe “the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching,” and for those United Methodists who believe such a statement is unbiblical, harmful, and an incitement to violence against LGBTQ+ people.

In their defense, reconcilers are not without convictions regarding these matters. They have them, and, when necessary, will act upon them. However, they believe the church is big enough and that unity is precious enough to accommodate people with diametrically opposing views.

A second group might be called liberalizers. Their ultimate goal is to dramatically liberalize the church’s sexual ethics, its understanding of gender, and its teachings on marriage. Liberalizers, leaning into the Bible’s demand for justice, particularly for those who have been marginalized and persecuted, maintain the church’s present teachings are, at best, based on outdated biblical scholarship, and at worst, grounded in homophobia. They are committed to creating a church where LGBTQ+ people are fully included in every facet of the church’s structure, and where their relationships are blessed and celebrated by the church.

They could tolerate people who think differently than they do, but not at the price of limiting in any way the full rights and responsibilities of church membership to their LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters. Local UM congregations must be prepared to receive an openly gay pastor, and UM pastors must not refuse to preside at same-sex weddings solely on their belief that such weddings are contrary to Scripture and the traditions of the church catholic.

The third group can justifiably be called conservatives. They want to conserve the church’s present standards because they believe they are rooted in Scripture, confirmed by centuries of church teaching, and are widely held by the majority of Christians around the world. They are happy to live in a church where all people are welcome to attend, but conservatives cannot endorse practices they deem incompatible with Christian teaching.

Hope for Unity

The COB’s fondest hope for the commission is for it to propose a plan that definitively resolves the acrimonious debate over the church’s sexual ethics and keeps the church united. Many United Methodists across the theological spectrum share the COB’s hope. However, most acknowledge it is a very tall charge, some think it an impossible one.

Prior to the 2016 General Conference most reconcilers believed the “Third Way Plan,” proposed by the Connectional Table, fit the bill. It seemed to them practical and fair, requiring compromise from both liberalizers and conservatives. For liberalizers, it made room, where possible, for same-sex marriage and the ordination of openly LGBTQ+ people. And for conservative clergy and annual conferences it did not force them to violate their principles when it came to same-sex marriage and the ordination of openly gay candidates.

Now, many reconcilers have reached the conclusion the plan is no longer viable. Most recognize that liberalizers regarded it as an insult to the LGBTQ+ community. The plan, according to them, essentially said LGBTQ+ people would only be tolerated where others in the church are willing to accept them. For LGBTQ+ advocates, the Connectional Table’s plan simply replaced one discriminatory regimen with another. At best, liberalizers regarded “A Third Way” as a step toward, but certainly not a plan that would solve their fight for full inclusion.

Conservatives, too, regarded the plan as a non-starter. It called for redefining marriage in a way that undercut Scriptural authority (the plan called for inserting the phrase “marriage is between two people” into the church’s Book of Discipline), and required them to be part of a church that allowed for practices the vast majority of global Christianity has and continues to proscribe.

Some chastened proponents of the Connectional Table’s “A Third Way” plan now acknowledge some kind of separation is necessary, but perhaps a kind of separation that would still allow for some form of overarching unity covering those with irreconcilable differences. Therefore, it is not uncommon now to hear talk of a “big tent,” an “umbrella,” or a “structural solution” as a possible way forward.

A potential plan, under such a scenario, would call for the creation of two or three autonomous entities, one each for reconcilers, liberalizers, and conservatives. In practice, the three entities would be required to choose new names and they would function as three separate denominations, but they would all exist under something that might be called The United Methodist Communion of Churches.

Under this proposal, the entities would work together in areas where there was clear and broad agreement – for example, on certain mission

Bishop Karen Oliveto. Photo by Patrick Scriven, Pacific Northwest Conference.

initiatives and in response to natural disasters. And, where willing, they would share and contribute to critical agencies like Wespath (the UM Church’s pension and health benefits service). From time-to-time, perhaps once every four or five years, the leadership of the various entities would, in a way similar to the present World Methodist Council, meet together to make decisions regarding those ministries and agencies they shared in common.

Such a plan would, at least in some sense, accomplish the COB’s two major goals: it would definitively resolve the debate over the church’s sexual ethics, and also maintain unity. The subsidiary entities would be autonomous, each with their own names, and the right to make their own decisions regarding doctrine, polity, and social issues, but all would operate under and partake in a United Methodist “communion.”

The plan would have the added benefit of liberating three distinct bodies to engage in creative forms of ministry without the constraints of a current institutional structure that people across the connection believe is too costly and bureaucratic for the severe demographic challenges the church will be forced to confront in the 2020s.

However, such a plan faces serious, and perhaps even insurmountable problems. First, the very aspects that make the plan commendable could lead to its undoing. To create such a communion would almost certainly require constitutional amendments for its creation. That means over two-thirds of the delegates at the 2019 General Conference would need to approve of it, and then it would need to garner two thirds of all the votes in all the annual conferences for ratification. Not only would that process be time consuming, delaying any implementation for one to two years, it would give opponents ample opportunity to rally just thirty-four percent of United Methodist annual conference delegates to defeat it.

Second, people would justifiably question the utility of creating an umbrella organization like a United Methodist Communion if, in fact, such a communion would not be substantially different from the existing World Methodist Council. Would it not be easier, critics might ask, to simply spin off organizations like UMCOR, GBGM, and Wespath, and just allow the three new entities or denominations to use or participate as they wish? A United Methodist Communion would provide only a patina of unity, seem superfluous to many, and so, in time, it would be short lived.

Third, many reconcilers affirm the UM Church’s doctrines, polity, and its stands on various social issues, they just don’t want to fight over them. They are inclined to give people wide latitude to believe and do as they please as long as they do not embarrass the church in the public square or the wider culture. In fact, they are so contented with the name United Methodist that they would be reluctant to yield it up to a supra-organization as the price for a semblance of unity.

Where the debate over the church’s sexual ethics is not raging – in places like Africa and The Philippines – the United Methodist name is widely respected. Many members in these regions would chafe at being asked to align with one of the three entities and thereby accept a new name when they are happy with the present one. They believe U.S. liberalizers are largely responsible for driving the battle over the church’s sexual ethics. They would prefer the liberalizers simply exit the church if they cannot live by its standards.

Liberalizers, however, have no interest in creating their own entity or denomination. Their stated goal has always been to redeem the one they are presently a part of. They too would resist giving up the name United Methodist. To be sure, they wouldn’t be satisfied with a church still short of fully including LGBTQ+ people, but they have fought long and hard for full inclusion, and would feel confident reconcilers would eventually see the light. So for a time, the liberalizers and reconcilers would remain united and continue to debate the church’s sexual ethics and teachings on marriage. Liberalizers would constantly be pushing for full inclusion and full participation. Left leaning reconcilers would show signs of yielding. And right leaning reconcilers would grow frustrated, discovering that the unity and peace they thought they had won was only fleeting, forcing them once again to make a definitive decision they hoped to avoid.

Conservatives too would likely have serious reservations. So much water has gone over the dam since the 2016 General Conference that they have little appetite for remaining yoked to liberalizers. The heightened acts of ecclesial defiance and Oliveto’s election have soured conservatives on the idea that unity can be preserved. Many would balk at finding themselves under an umbrella or big tent with the liberalizers who defied the church’s teachings or even the reconcilers who countenanced the defiance. And they would certainly be opposed to any configuration that forced them to acknowledge an openly gay person as their bishop.

Furthermore, a growing number of conservatives find no great benefit in the name “United Methodist,” indeed, some consider it a hindrance. Many of the denomination’s largest and fastest growing congregations do not feature the name on their signs or other forms of publicity. For instance, the two large congregations who exited from the Mississippi Annual Conference were simply known as Getwell Road Church and The Orchard. At this juncture some conservatives would regard a United Methodist Communion as a fiction at best, and at worst, a supra-organization that would continue to entangle them in unwanted alliances and continued fighting with liberalizers and reconcilers.

So, if a “big tent” or “umbrella” faces such daunting challenges what are other viable options?

Liberalizers Should Leave

A significant number of global conservatives believe they know the best way forward: liberalizers should simply leave the church. After all, the denomination has repeatedly rebuffed their attempts to liberalize its teachings, and it is likely to do so for the foreseeable future. Conservatives in this camp think this way forward can be implemented in one or two ways – amicably or legislatively and litigiously.

Under the much preferred amicable plan, the UM Church would graciously allow all liberalizer congregations and even annual and jurisdictional conferences to exit the denomination with all their property and assets, and they would apply no penalty for unpaid apportionments.

Under the more onerous legislative and litigious plan, the UM Church would close the legislative loopholes liberalizers have exploited in the past, and begin strictly enforcing church law with stiff sentences for all those who defied it. In short, the litigious plan calls for forcing liberalizers out of the denomination and any reconcilers who would abet or countenance their defiance.

These plans are siren songs for conservatives across the global connection. They are, by far and away, their preferred way forward. However, neither is likely to come to pass.

First, the idea that liberalizers will amicably leave the church is naïve at best, and delusional at worst. The plan fails to take liberalizers seriously. As stated above, they are not interested in creating a new denomination; they want to redeem the one they are a part of. They find offers to leave, even offers to leave with all their property and assets, to be insulting, as if they are fighting for their “piece of the pie.” Some conservatives like to tell themselves liberalizers do not want to leave because they know they do not have the financial resources to create their own church. This may or may not be true, but it’s beside the point. When you believe you are fighting for justice, you don’t surrender for property and assets. People who do that are called “sell-outs,” and that term is anathema to social justice advocates.

Second, the idea that liberalizers can be forced from the church is almost as far fetched as them voluntarily leaving. If the events of the past two or three years have definitively demonstrated anything, it is the truism that all the right laws in the church are of little avail if bishops and annual conferences are unwilling to enforce them. That is surely the case in the United States, and it will continue to be the case for years to come. The vast majority of U.S. bishops simply have no stomach for all the bad press that would surround church trials and the eviction of clergy and their colleagues from the denomination.

Second, the idea that liberalizers can be forced from the church is almost as far fetched as them voluntarily leaving. If the events of the past two or three years have definitively demonstrated anything, it is the truism that all the right laws in the church are of little avail if bishops and annual conferences are unwilling to enforce them. That is surely the case in the United States, and it will continue to be the case for years to come. The vast majority of U.S. bishops simply have no stomach for all the bad press that would surround church trials and the eviction of clergy and their colleagues from the denomination.

Given the structural shape of the church in the U.S., these dynamics are unlikely to change any time soon. Conservatives have to work mightily just to defend the church’s current sexual ethics and ordination standards. Closing loopholes and passing more robust legislation is possible, but it will take time and it is by no means inevitable. To be sure, conservative U.S. jurisdictional conferences will elect some conservative bishops who might strictly enforce the Discipline. However, reconcilers and liberalizers will elect far more of their own kind. Just as their predecessors found ways to thwart the will of General Conference, they will do the same, and they will do so even if future General Conferences manage to tighten church law and close loopholes.

Finally, it would seem reasonable for the Commission to reject these plans; they are simply non-starters. In that event, conservatives invested in them would need to acknowledge that they are on their own, and are likely in for a fight that will last for at least another decade or two.

Conservatives Should Leave

Another option would be for conservatives to leave the church. In the U.S., this is unfortunately happening every day, individual by individual, family by family, and in some cases, whole congregations. Many conservatives are as frustrated as reconcilers and liberalizers with the current state of affairs. They believe the church has reached an impasse, the differences are irreconcilable, and therefore further debate is only destructive. Some are clearly ready to leave the denomination – if the terms are acceptable.

But only some conservatives think this way. It is now likely that the majority of U.S. conservatives are in this camp, but the majority of conservatives in Africa, Europe, and The Philippines are not.

Furthermore, for many U.S. conservatives general church matters are not a high priority. They see little benefit in supporting several of the denomination’s general boards and agencies, particularly those they regard as hostile to the church’s sexual ethics, its teachings on marriage, and its ordination standards. In truth, many conservative pastors do what they can to shelter their people from the doings of U.S. bishops and many of the UM Church’s general boards and agencies. As the 2010 Call to Action Report revealed, United Methodists, not just conservatives, have little confidence in U.S. bishops, and believe the church’s bureaucracy is a drag on the denomination.

Therefore, at least some conservative pastors and congregations would leave under the following conditions: they are given title to all their property and assets, and they are immediately free of sending apportionment dollars to their annual conference and the general church.

But there are problems with this way forward too.

First, the majority of conservatives are not invested in this option. Indeed, where conservatives are at their strongest – in Africa and The Philippines – there is little or no interest in this plan.

Second, even in the U.S., a determined minority would reject, out of hand, any offer to leave. Why, they would justifiably ask, should we leave when we represent the majority of the global church, and when the church continues, at least on paper, to support sexual ethics, teachings on marriage, and ordination standards rooted in Scripture and the traditions of the church catholic? They would continue to ally with their global brothers and sisters to fight for what they think is right.

To be sure, a generous exit offer would bleed off some conservatives, but not all of them. Reconcilers and liberalizers would likely find themselves still locked in a church with no interest in reconciliation or liberalization when it came to the presenting issues. In short, there would be no definitive resolution to the matters that exercise us, and therefore precious little unity.

The Messy and Realistic Way Forward

Given this appraisal, it is no wonder the Council of Bishops seized on the creation of a commission. It allowed them to pass along the task of resolving the greatest challenge the UM Church has confronted in its nearly 50 year history. A task many believe they could have resolved by fulfilling their duty to promote the church’s teachings and seeing that its teachings and standards were followed.

Obviously, the commission needs our prayers, patience, and perhaps most importantly, our pragmatism. United Methodists need to disabuse themselves of the idea that the Commission on a Way Forward is going to produce a plan that definitively solves the debate over our sexual ethics and keeps the church united; it’s not. Given all that has happened in just the past year, the divisions are now too deep, and therefore, some are bound to find any plan of unity to be a fiction at best.

Realistically speaking, for those who support unity at any price, they will have to accept, at least in the short term, further battles over the church’s sexual ethics, teachings on marriage, and its ordination standards. Reconcilers, most liberalizers, and many conservatives all say they want unity, but they all still want it on their own terms. That’s undoubtedly a recipe for more church skirmishes.

And for conservatives who just want to be free of the fractious debate, they will have to accept that the way out could come at a steep price. It is possible the Council of Bishops will balk at any proposal allowing conservatives to leave with all their property and assets and the immediate cessation of apportionment payments. Such a stiff response would force those conservative congregations that wanted to leave into potentially protracted, costly, and uncertain legal battles over their property and assets. Other mainline denominations, particularly the Episcopal Church, have demonstrated how costly and bitter that path can be. And even if they were able to break free of the UM Church, they would face the challenge of either going independent or joining a new connection of like minded local churches. Either option would come with its own set of challenges.

It is likely, indeed probable, a mix of much of the above will come to pass no matter what the commission recommends, the COB proposes, and the called General Conference approves come February 2019. There are no good options, only less bad ones. And whatever option is proposed, some will not like it. Still, the number one priority should be ending the conflict definitively, so the church can focus on the mission of incarnating the ministry of Christ and making disciples.

The Commission on a Way Forward is likely to submit its recommendation no later than the COB’s April 2018 meeting. And the COB must publicly release a final proposal 230 days before the called 2019 General Conference, which means the proposal will be available for all to review no later than July 4, 2018.

For now, wise and faithful pastors and lay leaders will spend the interim providing their local churches with as much information as possible, and carefully preparing their local congregations to respond accordingly.

Walter Fenton is a United Methodist clergyperson and an analyst for Good News.

by Steve | Sep 15, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2017

By Faith McDonnell-

By Faith McDonnell-

In 1989, People magazine reviewed Ratushinskaya’s prison memoir, Grey is the Color of Hope. The review recounted how the then-exiled-in-the-West poet had been arrested in 1983 at the age of 29 and sentenced to seven years’ hard labor for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, possession of human rights documents, possession of articles about the Polish labor movement, and possession of anti-Soviet literature,” among other things.

A New York Times review of the book describes Ratushinskaya’s companions in the labor camp’s “Small Zone,” a restricted area for “particularly dangerous female political criminals.” According to the Times: “All of them were defiant nonconformists who chose imprisonment rather than renege on their political or religious principles. They included a leading activist of the Helsinki Watch committee, a recent convert to Roman Catholicism who received a 10-year term for helping an underground priest teach a children’s catechism class, a Pentecostal Christian and the editor of an underground, samizdat, journal dedicated to feminist issues such as the horrors of Soviet maternity wards…”

It is quite probable that the beatings, torture, vitamin-deficient diet, and extreme conditions under which Ratushinskaya spent four years contributed to the cancer that brought about her death. In his obituary of Irina Ratushinskaya for The Guardian, the Rev. Michael Bourdeaux puzzles, “precisely why she was singled out for such inhuman treatment remains a mystery.” He continues, “One might have expected that she would have been given an intimidating rebuke by the KGB and dismissed from her job. Instead she found herself confronting the full force of the Soviet law, but poetry in Russia was always dangerous.” Bourdeaux would know. He founded the British-based Keston College that for years provided information on prisoners of faith and conscience in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, including Ratushinskaya.

The People article reveals that 250 poems by this courageous dissident – who graduated in physics from Odessa University in 1976 and became a teacher – were written via a matchstick and a bar of soap. Her poems were smuggled out of the Small Zone by her husband, physicist and human rights activist, Igor Gerashchenko. He risked his own freedom to ensure that Ratushinskaya’s voice was heard by passing the poems on to Western journalists. Because of this initiative two books of her poetry were published in the United States while she was still in prison. And it was obvious from her poems that Ratushinskaya was freer as a labor camp prisoner than her jailers could ever be.

Her poem to which I refer most often when I am writing or speaking about the global persecution of Christians is entitled “Believe Me.” She wrote it the day after she was freed from the labor camp. It is a poem I use to inspire myself and others to pray for those who are persecuted for their faith. The poet’s early release came as part of the negotiations for the summit between Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik, on October 9, 1986. The next day she wrote this:

“Believe me, it was often thus

In solitary cells, on winter nights

A sudden sense of joy and warmth

And a resounding note of love.

And then, unsleeping, I would know

A-huddle by an icy wall:

Someone is thinking of me now,

Petitioning the Lord for me.

My dear ones, thank you all

Who did not falter, who believed in us!

In the most fearful prison hour

We probably would not have passed

Through everything – from end to end,

Our heads held high, unbowed –

Without your valiant hearts

to light our path.”

– “Believe me,” Irina Ratushinskaya, Kiev, October 10, 1986.

It must have seemed strange to write again in freedom, to write from a distance about the freezing cold solitary isolation cell known as SHIZO with which she had been so intimately acquainted. Ratushinskaya had been subjected to this torture on a regular basis for refusing to renounce her Christian faith, refusing to inform on fellow prisoners, and for refusing to say she would never write poetry again. Years later she still suffered from excruciating headaches because of a concussion she received when a brutal guard threw her headfirst against a wooden trestle in the cell.

On her first day waking up in freedom, Ratushinskaya was eager to put pen to paper. And she used the occasion to write a tribute to her intercessors. The former prisoner revealed how she felt tangibly the effect of their prayers: in a “sudden sense of joy and warmth and a resounding note of love” while “a-huddle by an icy wall.” Her words described the experience of many Christian prisoners of faith and the supernatural warmth they felt while in conditions that had no business feeling warm. The result of, as Ratushinskaya put it, “someone thinking of me now, petitioning the Lord for me.” A mystery, certainly, but undeniable when coming from the person who experienced this miracle, and especially from someone who frequently had been in trouble for speaking truth.

Ratushinskaya spoke of the “valiant hearts” that lit the path for those in the “most fearful prison hour.” Members of Congress – such as the human rights heroes Frank Wolf, Chris Smith, and Tom Lantos – did their part as advocates for the poet. People around the world became prayer warriors.

I first stumbled upon one of those valiant hearts, the Rev. Dr. Dick Rodgers, an Anglican priest and orthopedic surgeon, when I was wandering through England’s cathedrals in the summer of 1985. Rodgers was distributing leaflets about the poet. In 1986 Rodgers spent all of Lent inside a cage at St. Martin in the Bull Ring Anglican Church in Birmingham that functioned as a replica of Ratushinskaya’s prison cell.

Rodgers shaved his head the way that her head had been shaved and ate prison-style rations, to call attention to Ratushinskaya’s malnutrition-inducing prison diet of hard bread and rotted-fish broth. For an age in which there was barely any electronic communication, let alone social media, Rodgers brought the cause of this Christian dissident to the global community. Bourdeaux writes in his obituary for Ratushinskaya that “Irina came to believe that the huge publicity [Rodgers] engendered contributed to saving her life.”

Bourdeaux relates how on the morning of October 10, 1986, the news that Irina Ratushinskaya was free “upstaged the event for which the media had been waiting — the opening of the Reykjavik summit between U.S. president Ronald Reagan and the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.” He explains that Gorbachev wanted the world to know that he was serious about improving both international and domestic relations. He wanted to show the improvement in human rights brought about by perestroika (reconstruction).

Two months after Ratushinskaya’s release, she and Gerashchenko were allowed to leave the Soviet Union for medical treatment. While they were away they were stripped of Soviet citizenship and so settled in London. Ratushinskaya was also Poet in Residence at Northwestern University from 1987-1989. But after a few years of celebrity and popularity for Ratushinskaya, the West — not learning anything from the example of the Soviet Union — lost interest in the heroism of dissidents from the Soviet Union. In 1993, she and Gerashchenko had twin sons, Sergei and Oleg, and the family returned to Russia in 1998.

were away they were stripped of Soviet citizenship and so settled in London. Ratushinskaya was also Poet in Residence at Northwestern University from 1987-1989. But after a few years of celebrity and popularity for Ratushinskaya, the West — not learning anything from the example of the Soviet Union — lost interest in the heroism of dissidents from the Soviet Union. In 1993, she and Gerashchenko had twin sons, Sergei and Oleg, and the family returned to Russia in 1998.

In “Believe Me,” Ratushinskaya thanked those who remembered her, “who did not falter, who believed in us.” But it was she who did not falter. To quote her, she “passed through everything — from end to end” with her head “held high, unbowed.” Finally, she passed through suffering the tolls of cancer on a body that had already been tested by the harsh reality of Strict Regime Labor Camp No. 3. She left her beloved Igor once more, as she did when she was wrenched from him in the Kiev Courtroom and he called out, “Hold steady, darling, I love you!” to support her through the long years of separation.

Now Ratushinskaya is gone once more. We often speak glibly of those who have died “receiving their reward in heaven,” but Irina Ratushinskaya has a Hebrews 11 reward. “Some faced jeers and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment … the world was not worthy of them.” Irina and other valiant warriors of the era of Soviet persecution lit the path for me that brought me where I am today. And now, in the true freedom of Eternal Life, the poet is part of the great cloud of witnesses cheering on those of us still running our race.

Faith McDonnell is the Director of Religious Liberty Programs and of the Church Alliance for a New Sudan at the Institute on Religion and Democracy in Washington, D.C. Reprinted by permission. Editor’s note: On March 26, 1987, the Institute on Religion and Democracy presented its third Religious Freedom Award to Irina Ratushinskaya. At the reception, then Secretary of State George P. Shultz said of Irina, “In her dogged determination to live her own life and speak her own mind, regardless of the personal cost, she has taught others the meaning of human freedom.”

by Steve | Sep 15, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Perspective E-Newsletter

By Charles W. Keysor, Founding editor of Good News

The Risk of Renewal

By Riley B. Case-

When Charles Keysor wrote his article “Methodism’s Silent Minority” in the Christian Advocate in 1966, an article that basically launched the Good News movement, he spoke about numbers of Methodists who affirmed historic Methodism and were faithful and active in their local churches but were basically unrecognized and unappreciated in the larger councils of the church. Keysor referred to these orthodox believers as a “silent minority.” He suggested their numbers were larger than what church leaders had usually assumed.

Keysor’s analysis at the time was in contrast to liberal observers who insisted that “fundamentalism” (a pejorative label used to refer to all evangelicals) was a dying ideology with no future in the Methodist Church, or anywhere else for that matter. Keysor quoted his own professor at Garrett Seminary, Paul Hessert, who foresaw a continued eclipse of orthodox influence within the seminary-trained Methodist ministry, but who believed that such a perspective might continue among supply pastors and pockets of lay people.

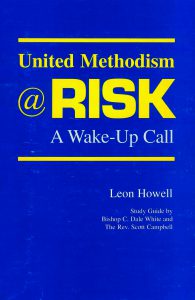

Surprise! Something happened on the way to extinction. According to the 2003 book, United Methodism @ Risk: A Wake-Up Call, produced by a group called Information Project for United Methodists, and introduced with great fanfare to the press and to the Council of Bishops, Methodism is in danger of being “taken over” by this very “silent minority” Keysor spoke about.

In what appears to be a near-state of panic, The Information Project charges that “powerful,” “well-organized and funded” conservative renewal groups (the book refuses to refer to them as “evangelicals”) would take the church to a place where “diversity and tolerance and breadth of spirit are in short supply.” The “progressive” bishops, seminary professors, and board and agency staff people who dominate the Information Project characterize the renewal groups as those who “look backwards to times when knowledge was feared, questioning was suppressed, and imagination was squelched.”

The book is a call to action. It argues that the renewal groups and the point of view they represent are to be unmasked and resisted, presumably so that United Methodism can be kept pure for “diversity and tolerance.” Tolerance, in this case, is translated to mean anything that counters the traditional orthodox vision for Christian theology, marriage, and sexuality.

One reads United Methodism @ Risk with sadness. How is it that evangelicals have been so long in the UM Church and yet are so clearly misrepresented and misunderstood? How did evangelicals go from being people whose faith was criticized at one time for being “privatistic,” and “individualistic,” to persons who are really motivated by a certain social and political agenda? When did evangelicals move from being people who simply wanted to be left alone to do ministry in a United Methodist tradition, to being persons who are power hungry and want to take over the church?

The book is an attack on evangelical renewal groups — but it is more. It is an attack on the Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church and upon many of the most loyal of the church’s members. The alarm is sounded not against people in power who oversaw the monumental decline of membership within the last several decades, but upon the people who believe that the people who are in power (bishops, seminaries, and boards and agencies) are not serving them well.

Consider the typical renewal group supporter: here is a couple in their sixties who have been loyal United Methodist all their lives. They have held most of the church offices; they have taught Sunday school; they have tithed. They have lived through a succession of pastors, some good, and some, while sincere, who didn’t believe much. They have agonized over Sunday school material that they didn’t understand. They have wondered why their local church struggles while the nearby Baptist church thrives.

Our United Methodist couple is finding that a lot of their spiritual nurture is coming not from their church but from a neighborhood Bible study. They struggle on how to answer their friends who show them newspaper clippings of a United Methodist bishop who publicly scorns the church’s affirmation that Christ did truly rise from the dead.

Our couple’s own children, away from home, are not affiliating with a United Methodist church. One daughter, who claims she never heard the gospel in her home church, was converted in college through Inter-Varsity, and is active in an independent church. A son, after marriage, attended a United Methodist church in the city until he and his wife were attracted to a Nazarene church with an active children’s program.

The wife of our couple has been active in United Methodist Women, and enjoys the company of other women in the group, but finds the programs boring. The man has sat through numbers of charge conferences where a district superintendent talks grandly about “the connection” and the importance of paying apportionments. On Mission Emphasis week the “missionary” who speaks at their church is really a person who did a two-week volunteer mission trip to work on a church parsonage in another state. There was no mention of Jesus in the presentation.

Our couple has identified with Good News or the Confessing Movement or Aldersgate Renewal Ministries because they are offer a message of hope. They understand that each ministry is working for change in its own unique way. Our couple may not understand everything implied in the words “doctrinal integrity” but they are aware of the difference between preachers who preach on the necessity of being born again, and those who offer vague homilies on “hope” or “love.” They respond to a Mission Society missionary [now TMS Global] who is working on new church starts in Bolivia.

This couple, however, along with 90 percent of all other United Methodists, would fall in the category of what Bishop Joseph Sprague has labeled “Christo-centric exclusivism that ipso facto prepares the soil of stiff-necked, exclusivistic arrogance.” The people who support the evangelical renewals groups are not “extremists,” nor could they be considered “right-wing,” if one were to understand these words in the context of the whole of Protestantism in America (and around the world, for that matter).

A profile of the supporters of the several evangelical renewal groups shows them to be among the most loyal and faithful United Methodists in their local churches. They pay their apportionments and pray for their bishops. Many claim if it were not for one or several of the renewal groups they would no longer be United Methodist. Neither they, nor the groups they support, wish to “take over” the denomination for a very simple reason. They understand the essence of the denomination to be the local church, not the seminaries, nor the boards and agencies, nor the episcopacy. They also understand that the purpose of the church is to save souls and nurture disciples, not to make public declarations about government public policy.

This is not to say, however, that renewal group supporters, and perhaps the vast majority of United Methodists, are content that their own convictions are often undermined by the seminaries, their own understandings of the Bible’s view on celibacy and faithfulness are continually being challenged, and that their “leaders” claim to represent them while denouncing a fellow United Methodist who is President of the United States.

United Methodism is indeed at risk. It is in the midst of a 100-year decline. According to Roger Finke and Rodney Stark, in their book, Acts  of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion (University of California Press, 2000) the number of Methodist adherents in America has decreased from 84 of every 1,000 Americans in 1890 to 36 in 1990. The years of the decline correspond exactly to the years that liberalism and institutionalism have dominated Methodism.

of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion (University of California Press, 2000) the number of Methodist adherents in America has decreased from 84 of every 1,000 Americans in 1890 to 36 in 1990. The years of the decline correspond exactly to the years that liberalism and institutionalism have dominated Methodism.

From 1970 to 2003, membership of the United Methodist Women has declined by 54 percent. One would think, whether liberal or evangelical, that such statistics would call for some sort of reform, or at least some self-examination. Something clearly in not going well. Yet when the renewal groups call for reform of the Women’s Division it is absurdly interpreted as an attack on women. Women’s ministries are alive and well in numbers of churches, but are criticized as being “unofficial” because they do not have the blessing of the Women’s Division (United Methodist Women).

In their sociological analysis Stark and Finke distinguish between “low tension” and “high tension” churches. Low tension churches, where few demands are made (read “tolerance,” “diversity,” and “breadth of spirit”) are becoming increasingly irrelevant and are dying in America. High tension churches, with an emphasis on moral and doctrinal values, are growing. Stark and Finke argue that it seems impossible that once a group becomes low tension and starts down the road to decline, it can ever be reclaimed. There may be an exception, however, in United Methodism. If there is it will be because of groups like Good News and the Confessing Movement. They have done studies in several conferences to substantiate statistically what many of us already know instinctively, namely, that liberal churches are dying and evangelical churches are growing.

Stark and Finke are doing sociological work in a secular setting. If the Information Project really wants “dialogue” perhaps a discussion of the Stark and Finke book would be a good place to begin.

Riley B. Case is the author of Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon). He is a retired United Methodist clergy person from the Indiana Annual Conference, the associate director of the Confessing Movement, and a lifetime member of the Good News Board of Directors. This adapted essay originally appeared in the September/ October 2003 issue of Good News.

by Steve | Sep 15, 2017 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2017

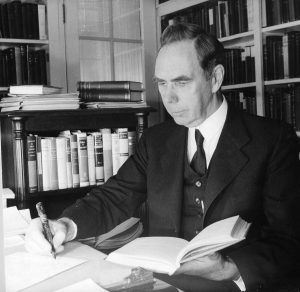

Dr. Edwin Lewis. Photo courtesy of Drew University.

By James V. Heidinger II-

Debate has been renewed in recent months about the role of doctrine for United Methodists. What is the place, for example, of orthodox Christian doctrine in our church? For years we have heard that we are not a creedal church; that Methodists have been more interested in “faith working through love”; that Methodists have always been more experiential than doctrinal; that doctrine should not be the basis for juridical action or for coercion.

There is truth in some of this, no doubt. In 1952, the bishops of The Methodist Church said in addressing that year’s General Conference that “Our theology has never been a closely organized doctrinal system. We have never insisted on uniformity of thought or statement.” However, the bishops went on to say in that address, “There are great Christian doctrines which we most surely hold and firmly believe.” Commenting on this address, Bishop Nolan B. Harmon said, “Methodists have always heatedly rejected the idea that Methodism is simply a ‘movement’ with no formal doctrine” (Understanding the United Methodist Church, Abingdon, 1974).

The oral tradition claiming Methodism to be a non-creedal church has a history that reaches back at least to the early 1900s, the time of the fundamentalist/modernist controversy. Methodism at that time had just experienced the unpleasant controversy about its holiness message. General Conference took action in 1894 to bring holiness evangelists under the church’s strict control. Many left Methodism to form no less than ten different holiness groups. They believed the Methodist Church was not being faithful to Wesley’s understanding of sanctification and perfect love.

In the face of the bitter controversy beginning to brew over the fundamentalist/modernist debate, Methodism was determined to avoid more division. The result was that Methodism moved even further away from careful creedal and doctrinal formulation to a mood of greater openness, tolerance, and emphasis on Christian love in action. There was also the feeling that with so many urgent social ills in America’s growing cities, theological debate might prevent the church from meeting human needs.

This led to a growing antipathy toward creeds, a pattern that can be seen in the periodical literature of 1910-1920. The trend clearly was to shift focus from creeds to human needs. A.H. Goodenough wrote in the Methodist Review in November, 1910: “Creeds have had their day. They are no longer effective. Without doubt, they were well intended. Possibly they have done some good—they certainly have done much harm. The church has been loyal to her creeds, and has spent much good blood and splendid brains in the defense of them. All this was considered the very essence of Christianity. It was child’s play, as we now see it, and in some instances paganism.… The creeds are retired to the museums and labeled ‘Obsolete.’”

Seeing division and strife around them from the fundamentalist/modernist controversy, Methodists were more than ready to relax their attention on creedal and doctrinal formulation. One New York pastor, Philip Frick, wrote with near exhilaration an article entitled, “Why the Methodist Church Is So Little Disturbed by the Fundamentalist Controversy,” (Methodist Review, 1924), in which he gives the reason as being Methodism’s lack of dogmatic creedal assertion.

Further evidence of the growing antipathy to creedal formulation at this time can be seen in the change in requirements for membership. In 1864, the Methodist Episcopal Church required members to subscribe to the Articles of Religion. This requirement was removed in 1916. Belief in the Apostles’ Creed continued to be required after 1924 as it was included in the baptismal ritual, but it, too, was dropped in 1932.

It may well have been in response to General Conference’s dropping of the Apostles’ Creed in 1932, as well as the popular preference for using the new Social Creed rather than theological creeds, that led to Edwin Lewis’ article of alarm over “The Fatal Apostasy of the Modern Church.” Lewis, a professor of systematic theology at Drew Theological Seminary, wrote stinging words in response to these changes: “But what does the modern church believe? The church is becoming creedless as rapidly as the innovators can have their way. The ‘Confession of Faith’ — what is happening to it? Or what about the ‘new’ confessions that one sees and hears — suitable enough, one imagines, for, say, a fraternal order. And as for the Apostles’ Creed — ‘our people will not say it any more’: which means, apparently, that ‘our people, having some difficulties over the Virgin Birth and the resurrection of the body, have elected the easy way of believing in nothing at all — certainly not in “the Holy Catholic Church”.’” (Religion in Life, Autumn, 1933).

So this era saw a transition from doctrinal and theological concerns to a growing new interest in, if not preoccupation with, social ministry.

John Wesley.

The church focused not on the content of belief, for that could be divisive, but rather upon Christian love in action through social ministry. This inattention to theology may have been partially responsible for Methodism’s tragic susceptibility to the influence of liberal theology and German philosophy that were rapidly finding a home in our Methodist seminaries.

The move away from doctrine during this period also provided natural cover for pastors who were being trained in the emerging liberal theology. Many could surrender the supernatural elements of apostolic faith — the Virgin Birth, the deity and miracles of Jesus, and his bodily resurrection — and continue on in ministry without ever having to talk much about those things. Social ministry was in, theological definition was out.

This helps us understand the oral tradition that has come down to us today. It is this: United Methodism is not a creedal church, we live in a changing world, and doctrines we used to teach may not be relevant today. And most recently, folks in one annual conference were warned by letter of a “movement away from an evolving and ever-changing understanding of God guided by the Holy Spirit.” Of course, “an evolving and ever-changing understanding of God” could never be expressed in a creed or traditional formulation, for it would be forever changing. The best folks might get would be a list of “Affirmations of the month,” but not “the faith once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3).

Looking again at our Wesleyan tradition

But is the oral tradition really our Wesleyan theological tradition? One senses we have done violence to both Wesley and American Methodism with such sloppiness and ambiguity.

Charles Yrigoyen, Jr., in his helpful book, Belief Matters (Abingdon, 2001), reminds us that the church’s doctrine helps us understand the biblical message in a “clearer, holistic, more organized way,” and thus we can communicate it more effectively. Unfortunately, many United Methodists today don’t really understand that message. He also reminds us that the official doctrine of the church “protects us from false and subversive teachings.” Pastors have the responsibility to feed their flocks and make sure they are not grazing in toxic pastures.

Belief certainly mattered to John Wesley, despite the claims of the revisionists. Wesley insisted on doctrinal faithfulness. In 1763 Wesley drafted a Model Deed which stipulated that the pulpits of the Methodist chapels were to be used by those persons who preached only those doctrines contained in Wesley’s New Testament notes and his four volumes of sermons. If a preacher didn’t conform, he was out within three months. Wesley would never have shrugged off reports of an errant preacher by saying, as do many today, “Well, we Methodists think and let think.” (He did say that, of course, in “The Character of a Methodist,” but let’s quote his entire sentence: “But as to all opinions which do not strike at the root of Christianity, we think and let think.”)

While Wesley had a refreshing breadth of spirit about him, there were doctrines he viewed as essential to the faith. Robert Chiles, concurring with Methodist theologian Colin Williams, lists the doctrines that Wesley insisted on at various times in his ministry as “original sin, the deity of Christ, the atonement, justification by faith alone, the work of the Holy Spirit (including new birth and holiness) and the Trinity” (Chiles citing Colin Williams, John Wesley’s Theology Today). This is simply apostolic Christianity.

Yes, we United Methodists take doctrine very seriously. Each person seeking to become a clergy member within our denomination is asked, “(8) Have you studied the doctrines of The United Methodist Church? (9) After full examination, do you believe that our doctrines are in harmony with the Holy Scriptures? (10) Will you preach and maintain them?” (Book of Discipline, Par. 327). Candidates are expected to answer in the affirmative.

The church, in fact, takes doctrine seriously enough that a bishop, clergy member, local pastor, or diaconal minister may be charged formally with “dissemination of doctrines contrary to the established standards of doctrine of The United Methodist Church” (Discipline, Par. 2624.1f), which can lead to a trial. Doctrine is not tangential to the people called Methodists.

Alister McGrath, professor at Oxford, has warned that “Inattention to doctrine robs a church of her reason for existence, and opens the way to enslavement and oppression by the world.” Certainly, attention to doctrine will help United Methodists understand that our doctrinal standards are not, have never been, and must never be, “evolving and ever-changing.” That would be a guarantor of continued confusion and further decline.

James V. Heidinger II is the publisher and president emeritus of Good News. A clergy member of the East Ohio Annual Conference, he led Good News for 28 years until his retirement in 2009. Dr. Heidinger is the author of several books, including the recently published The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism (Seedbed). This essay originally appeared in the September/October 2003 issue of Good News.

By Walter Fenton-

By Walter Fenton-

Second, the idea that liberalizers can be forced from the church is almost as far fetched as them voluntarily leaving. If the events of the past two or three years have definitively demonstrated anything, it is the truism that all the right laws in the church are of little avail if bishops and annual conferences are unwilling to enforce them. That is surely the case in the United States, and it will continue to be the case for years to come. The vast majority of U.S. bishops simply have no stomach for all the bad press that would surround church trials and the eviction of clergy and their colleagues from the denomination.

Second, the idea that liberalizers can be forced from the church is almost as far fetched as them voluntarily leaving. If the events of the past two or three years have definitively demonstrated anything, it is the truism that all the right laws in the church are of little avail if bishops and annual conferences are unwilling to enforce them. That is surely the case in the United States, and it will continue to be the case for years to come. The vast majority of U.S. bishops simply have no stomach for all the bad press that would surround church trials and the eviction of clergy and their colleagues from the denomination.  By Faith McDonnell-

By Faith McDonnell- were away they were stripped of Soviet citizenship and so settled in London. Ratushinskaya was also Poet in Residence at Northwestern University from 1987-1989. But after a few years of celebrity and popularity for Ratushinskaya, the West — not learning anything from the example of the Soviet Union — lost interest in the heroism of dissidents from the Soviet Union. In 1993, she and Gerashchenko had twin sons, Sergei and Oleg, and the family returned to Russia in 1998.

were away they were stripped of Soviet citizenship and so settled in London. Ratushinskaya was also Poet in Residence at Northwestern University from 1987-1989. But after a few years of celebrity and popularity for Ratushinskaya, the West — not learning anything from the example of the Soviet Union — lost interest in the heroism of dissidents from the Soviet Union. In 1993, she and Gerashchenko had twin sons, Sergei and Oleg, and the family returned to Russia in 1998.

of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion (University of California Press, 2000) the number of Methodist adherents in America has decreased from 84 of every 1,000 Americans in 1890 to 36 in 1990. The years of the decline correspond exactly to the years that liberalism and institutionalism have dominated Methodism.

of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion (University of California Press, 2000) the number of Methodist adherents in America has decreased from 84 of every 1,000 Americans in 1890 to 36 in 1990. The years of the decline correspond exactly to the years that liberalism and institutionalism have dominated Methodism.