by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Photos by David Parks –

Jonathan Tremaine (JT) Thomas of Civil Righteousness, a ministry out of Ferguson, Missouri.

In the midst of waves of protests around the globe in response to the death of George Floyd, there were also worship services in communities that brought Christians of different ethnicities together to sing and pray, mourn and lament.

In the week after Floyd’s death, open-air services were conducted at the street corner of 38th and Chicago in South Minneapolis – the site of Floyd’s death – featuring gospel music, evangelistic preaching, calls for racial justice, Christian reconciliation, and the infilling of the Holy Spirit.

The services were launched by Pastor Curtis Farrar of the Worldwide Outreach for Christ, a congregation located at the street corner for 38 years. As protesters and mourners flocked to the memorial site, Farrar’s congregation offered free water, food, and antiseptic spray. From a street corner platform, he preached and members of his congregation led worship and prayer. Farrar was also joined by young evangelists such as Christophe Ulysse of Youth With a Mission (YWAM); Yasmin Pierce with Circuit Riders, a ministry from Southern

California; and Jonathan Tremaine (JT) Thomas of Civil Righteousness in Ferguson, Missouri.

“I’m seeing that people are responding in a positive way,” Farrar told a television station in Minneapolis. “I’ve never seen so many people come together on this corner. I’ve been here 38 years and I can see the peace and camaraderie and everyone’s helping one another.”

“This is a wakeup call to the world that we’re all morally bankrupt apart from God,” Ulysse told the Brantford Expositor. “There are so many narratives that are trying to hijack what’s going on. But this racism is a deep thing that we need a higher power to address.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”

Working with Farrar, Ulysse said that, during his time at the Floyd memorial, he saw hearts “turn from hatred, resentment, bitterness, and hopelessness,” as people of different races wept and hugged each other. He hoped that his message to the protesters and mourners would ultimately empower them to be “carriers of hope.”

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Courtney Lott –

Original art by Sam Wedelich (www.samwedelich.com).

“Greet all God’s people in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 4:21)

It’s the simplest phrase tacked on to the end of a letter. One we possibly pass by quickly, viewing it as a nice sentiment, and little else. We may even believe it’s a command easily and painlessly applied to our lives. Definitely not one that needs a closer look.

Sure. I’ll say hello to the people at my church. Box checked. Dust off hands. Done. Here in Texas, we pride ourselves on welcome, after all. It’s deeply ingrained in our culture. Even in the big cities and traffic jams, strangers wave to each other, smile (which has been a lot more difficult while wearing masks during COVID!)

But is it really so simple?

A box easily ticked off? A bland sentiment? Or does it dig deep into what it means to be part of the bride of Christ? Considering the fact that Paul uses it in the closing of multiple letters to multiple churches, chances are, it’s not a simple admonishment we ought to skim over.

Beyond the literal meaning of the Greek word for “greet” — “welcome” — the heart of the concept strikes deep to a desire ingrained in all of us: to not only be acknowledged by others, but to be welcomed in, to be seen without filters and still accepted. For a moment of eye-contact, a genuine question after one’s well-being, true interest in what makes you a unique image bearer.

Throughout my childhood, I often felt brushed aside. I was weird. I’m still weird. My overactive imagination — and sensitive spirit — categorized me as an oddball most of my peers either avoided or teased. I usually didn’t feel welcome at school, and at one point, begged my mom to teach me at home so I could avoid these painful interactions.

This lack of greeting left me with a deep sense that I didn’t belong, that no one wanted me around, and that there was something innately wrong with who I was. I hid myself away in books and stories, seeking out an imaginary community where I was accepted fully, weirdness and all.

I prayed nightly for a friend. For one who loved me as David loved Jonathan. Someone whose soul knit itself to mine. I have distinct memories of asking God to send me a peer who would not only share in my similar interests, laugh with me, cry with me, but who would call me out on things, make me better.

Then, in junior high of all places, the youth of my church opened their arms to me. In our mutual awkwardness of puberty, pimples, and prepubescent pensiveness, we found community with each other as we played stupid messy games and — still sticky with random food items — delved into the pages of scripture.

For the first time in my entire life — inside and out of the four walls of a church building — I found a sense of home, belonging, purpose. This simple act of kindness didn’t heal all of my insecurities, most of which still live in my heart as ugly weeds, but it healed much within me, strengthened me to do the same for others.

Thus empowered, making others feel welcome became a large part of my mission in life. It hasn’t always been easy. My own insecurities sometimes still tempt me to sidestep “weirdos” lest my association with them make me unwelcome again. When this temptation comes, I have to remind myself of what has been done for me, of my own little story of social salvation.

My experience hardly reflects the intense sense of misery others have experienced when it comes to rejection. Those who have experienced racism or discrimination due to their sexuality have suffered deeply and in ways I can’t even begin to imagine. The path they walk is a unique kind of pain I’m not familiar with.

The solution to our problems, however, looks very similar, and it’s found in this beautiful verse. Greet all God’s people in Christ Jesus. Greeting someone affirms the dignity already present in our fellow image bearers. It acknowledges that we are all messed up, but that if Jesus can love us that way, we can love each other that way as well.

Sometimes, like the religious leaders in Jesus’ parable about the good Samaritan, we sidestep those we view as “unclean.” As if their unique brand of sin will rub off on us if we get too close. When we are tempted to fall into this, we are called to remember how Jesus dealt with the “unclean.”

He touched lepers, curing them of their disease. He gripped the hands of those long dead, filling them again with life. He cleaned his disciples’ nasty feet. Jesus drew near to those everyone else would have avoided, in a sense, welcoming those no one else would. He did what the rest of us couldn’t do.

If anyone else embraced one of these, they wouldn’t be able to enter the temple, to step foot near the presence of YAHWEH. But Jesus’ simple touch cleansed, healed. Ultimately, he became unclean for us, making a way for us to approach the Holy God of the universe.

By his wounds we are healed.

By his uncleanness, we are made clean.

By his welcome, we are welcomed.

May we go and do likewise.

Courtney Lott is the editorial assitant at Good News.

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Jim Patterson

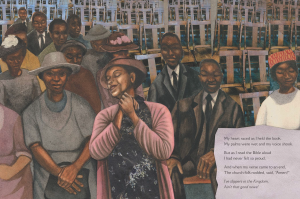

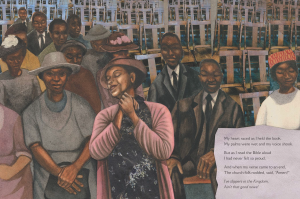

Art from the book By and By: Charles Albert Tindley, The Father of Gospel Music, written by Carole Boston Weatherford and illustrated by Bryan Collier. Image: Simon & Shuster.

Disbelief is the most satisfying response Carole Boston Weatherford gets from children about her books featuring notable African Americans.

“Kids just can’t believe that our nation allowed those kinds of injustices to visit upon so many people,” said Weatherford, a poet who has written children’s books on Fannie Lou Hamer, Harriet Tubman, Lena Horne, and others.

“I want them to be appalled,” she said. “I want them to be shocked that (slavery and racial discrimination) happened, but I also want them to be inspired that my subjects overcame those injustices … and persisted in reaching their potential and in making contributions to their communities and to larger society.”

Weatherford, who grew up as a United Methodist and was married for 20-some years to a United Methodist minister, considers it a mission to help correct the dearth of books about African Americans she experienced growing up.

“There were hardly any,” she said. “But when I became a mother, I noticed that there were more books that featured children of color for them.”

Her latest subject is Charles A. Tindley, a Methodist Episcopal clergyman sometimes called “The Prince of Preachers” and one of the founding fathers of gospel music. He was pastor of East Calvary Methodist Church in Philadelphia — now named Tindley Temple United Methodist Church — from 1902 to 1933.

His hymn, “I’ll Overcome Someday,” was one of the roots of the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” He wrote other gospel music standards, such as “(Take Your Burden to the Lord and) Leave It There,” “Stand by Me” and “What Are They Doing in Heaven?”

Tindley, born in 1851 the child of a slave father and a free mother who died young, received no formal schooling as a child — instead being hired out as a field hand. He taught himself to read from newspaper clippings lit by glowing pine knots.

Pursuing whatever education he could afford — night schools and correspondence courses, mostly — while working to support himself, he relocated to Philadelphia with his wife, Daisy, and worked as a church custodian. From there, he progressed to being the pastor of the very same church and writing many memorable gospel songs.

In By and By: Charles Albert Tindley, The Father of Gospel Music, illustrated by Bryan Collier, Tindley’s rather incredible rise is told in lilting verse by Weatherford.

“My life is a sermon inside a song/I’ll sing it for you/Won’t take long,” the book opens.

The illustrations by Collier are vivid and striking, mixing collage and watercolor painting. He has illustrated many children’s books about African Americans including Rosa Parks, Langston Hughes, Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, and contemporary musician Trombone Shorty.

“I think Tindley is a testimony to endurance and aspiration,” Collier said. “His insatiable need to learn and read, you can see that theme through a lot of different people like Frederick Douglass and many others growing up in the era of America that he grew up in, when the odds were totally against them to do what he did.”

Collier said his illustration style is influenced by his grandmother, who made quilts when he was a kid. “That’s the collage aspect of it. I try to use earth tones and bright colors for juxtaposition to make it pop. I use family members and friends to pose for the book, so we see ourselves and they can see themselves in books.”

Collier used to play as a child in an abandoned Pocomoke City, Maryland, church named for Tindley. It has since been torn down. Tindley was born in Berlin, Maryland, about 30 miles north of Pocomoke City.

“Every year, they do Tindley Day in Maryland as well as in Philadelphia,” he said. “So I had known about it and had been at the celebration picnics on Tindley Day.”

Collier has projects coming up about a mother’s writing directed to her unborn son and a reinterpretation of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.”

Weatherford is working on a book about Henry Box Brown, who in 1849 mailed himself in a wooden box from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia to escape slavery.

No matter how much historical context Weatherford shares when addressing children about her books, she says many are “confused” and ask the same questions:

“Did it really happen?”

“Who made those stupid rules?”

“Why did white people treat black people so badly?”

“They’re constantly trying to figure out how they should respond to history and also to injustices they see in their own lives,” she said. “Bullying in school, how do I respond to that? So kids are learning to navigate situations and they are forming their own values.

“I do hope that my books play some role in shaping their values and helps them form their own system of justice.”

Jim Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee.

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By David Watson –

Photo by Emre Can, Pexels.com.

Here is a simple truth about the human condition: we cannot save ourselves. This assertion flies in the faith of so much Western individualism. We think of ourselves as agents who shape the world around us. We prize self-determination and self-sufficiency, and to some extent we do have power over our lives. There are two areas, however, over which we have no control: sin and death. We are helpless before these. We all sin, and we will all die. We cannot save ourselves, but there is one who can save us, who in fact died to save us.

In his sermon “The Scripture Way of Salvation,” John Wesley, Methodism’s founder, addresses the question, “What is salvation?”

“The salvation which is here spoken of is not what is frequently understood by that word, the going to heaven, eternal happiness. It is not the soul’s going to paradise, termed by our Lord, ‘Abraham’s bosom.’ It is not a blessing which lies on the other side of death; or, as we usually speak, in the other world. The very words of the text itself put this beyond all question: ‘Ye are saved.’ It is not something at a distance: it is a present thing; a blessing which, through the free mercy of God, ye are now in possession of. Nay, the words may be rendered, and that with equal propriety, ‘Ye have been saved’: so that the salvation which is here spoken of might be extended to the entire work of God, from the first dawning of grace in the soul, till it is consummated in glory.”

Wesley most certainly believed in eternal life. His point, though, is to guard against the reduction of salvation to “going to heaven.” We are saved in the present, he insisted. Salvation includes all the work that God does in our lives, from that very first moment in which we feel that our lives may not be right just as they are. Perhaps we begin to believe that we aren’t living in the right way. Perhaps we start to feel the emptiness of a life focused on material pursuits. These moments are the beginning of salvation. God is leading us out of sin into holiness, and thus out of death into life. Indeed God must lead us if we are to make this journey at all. We cannot save ourselves. We have to be saved.

Salvation From Sin. “Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death?” (Romans 7:24). Paul has spent the previous ten verses talking about the conflict that occurs within a person who at some level knows what is right, but is simply unable to do it. “For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do” (7:19). Sin, as Paul describes it, is not just an action we commit. It is a force in the cosmos exerting itself upon human will. Sin is all the “gone-wrongness” of creation, and one of its chief manifestations is the human rebellion against God. Yes, Paul says, God gave us the law, and the law can tell us what is right. This doesn’t mean, however, that we can do what is right. Left to our own devices, we will inevitably succumb to the influence of sin upon our lives. Thus at the end of the chapter, it’s as if Paul throws up his hands in frustration. He cries out in self-condemnation: “Wretched man that I am!” thus giving voice to the pathos of the human condition. “Who will rescue me from this body of death?” He has tried to rescue himself, but he cannot. He needs a Savior.

This section of Romans (7:14-24), can be a bit puzzling, since Paul is writing this after he has been saved through Christ. How can Paul say of himself, after his encounter with Christ, “I am of the flesh, sold into slavery under sin” (7:14)? A constitutive feature of the Christian life is that we are no longer in slavery to sin. The answer is that Paul is not speaking of his current condition, but rather about what he used to be. In so doing, he gives voice to the human condition. He speaks on behalf of unredeemed humanity. We try to save ourselves, but we cannot. We need a Savior, and, thanks be to God, we have one.

Chapter 8 of Romans is the answer to chapter 7. By “sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and to deal with sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, so that the just requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit” (8:3-4). Through Christ, God has broken the vise-grip of sin on our lives. Because Christ assumed our human nature in its fallenness, we can be free. We’re no longer addicted to sin. In 2 Corinthians 5:21 Paul puts it this way: “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” Christ has made it possible for us to become righteous. Yes, we can still sin. We can most certainly reject God’s gracious and undeserved offer, but unlike before, we can both know what’s right and do what’s right. We no longer live according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit.

Paul’s language can be confusing sometimes. His opposition of “flesh” and “spirit” may lead us to believe that he felt the material world (particularly our physical bodies) to be bad, and only our souls to be good. The worldview of Judaism, however, affirms the goodness of creation. In Genesis 1, God saw what he had made and pronounced it “very good.” “Flesh” and “spirit” for Paul are shorthand terms, referring to our redeemed selves and our unredeemed selves. We once lived “according to the flesh” (in other words, as unredeemed people), but now we live life in the Spirit (as redeemed people).

Can we still sin? Indeed we can, but we don’t have to do so. Christ has saved us. He has done what we could not.

Salvation from Death. Followers of Jesus are saved from sin, and thus we are saved from death. Genesis 2:15-17 is the first biblical passage to connect sin and death: “The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, ‘You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die.’” We know how the rest of this story goes.

It is an uncomfortable truth of human existence that we are all going to die. These mortal bodies will fail. But then what? Do we simply vanish into nonexistence, or is there something more? Paul is clear that we can choose death. We can choose eternal separation from God, if that is what we really wish. Christ died, however, so that we can have life, and not just new life in the present, but eternal life with God. Paul describes Jesus as “the first fruits of those who have died” (1 Corinthians 15:20). This is an agricultural metaphor. The first fruits were gathered before the general harvest. Jesus was raised, and we will be raised as well. And if we receive the salvation that Christ offers us, we will be raised to eternal life in a renewed heaven and earth.

God is the source of all life, the ground of all being. As we draw near to God, we draw near to life. As we rebel against God, we embrace death. Righteousness is life-giving. Sin is life-denying. Paul writes in Romans 6:20-23:

“When you were slaves of sin, you were free in regard to righteousness. So what advantage did you then get from the things of which you now are ashamed? The end of those things is death. But now that you have been freed from sin and enslaved to God, the advantage you get is sanctification. The end is eternal life. For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

To break this down a bit, Paul is saying that sin once had such a hold on our lives that God’s righteous will held no sway over us. We were “free in regard to righteousness,” which is not a good thing. Such “freedom” from God is actually enslavement to sin, and the pathway of sin is a death march. Yet now, Paul says, we no longer serve sin, but God. Rather than death, we receive sanctification. This means we get to share in God’s holiness. We are set apart from the world by being freed from sin and empowered to live in a new way. If sin creates a rift between people and God, holiness is the healing of that rift. We are drawn to God, and the result is life, not just now, but forever.

Death is painful. It is often painful for those who die, and it is certainly painful for those who are left behind. Our grief at the loss of a loved one can be overwhelming. Grief is both natural and appropriate in such times. Christians, however, grieve differently from others. We grieve, but not as those without hope (1 Thessalonians 4:13). “Listen,” Paul writes, “I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. For this perishable body must put on imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality” (1 Corinthians 15:51-53). The hope that we have in Jesus Christ tempers our grief, and we give thanks to God that we might once again be with those whom we love in eternal life.

Making all things new. For each of us who follow him, Jesus is a personal Savior. Indeed, this was one of Wesley’s great insights during his famous Aldersgate experience: Jesus died not just for all, but for him – personally. While we affirm the personal nature of salvation, however, we should also recognize that salvation is more than this. Jesus is the Savior of the whole universe. As noted above, sin is not just a personal matter, but a cosmic one. It is a rupture in the moral fabric of creation, and we see its effects in manifold ways. It comes to bear on our friendships, our families, our churches, and the many institutions in which we participate. Our marriages, companies, schools, and even nations can be marred by sin and turned toward death.

The personal salvation each of us experiences is part of God’s redeeming work throughout all of creation. In Revelation 21:5, God declares from his throne, “See, I am making all things new.” Paul speaks about a “new creation” in which those of us who are “in Christ” participate (2 Corinthians 5:17). “Everything old has passed away,” he writes. “See, everything has become new!” God’s will is to redeem and renew what has been corrupted by sin and death. To be saved is to be drawn into God’s work of renewal.

As I write this, the United States is boiling over with pain, anger, and fear. The very fabric that binds us as a nation is strained to the point of breaking. We look for someone or something to save us. The contenders are numerous: the President, his electoral challenger, the press, some grassroots movement…. Make no mistake, the choices we make as responsible citizens do matter. Yet they cannot save us. Only Christ can do that. Laws can change behavior, but they cannot change hearts. If we want peace and justice in our land, we must work and pray for God to change hearts of stone to hearts of flesh. We all need to be saved, as individuals and as a society. We need not only a personal Savior, but the Savior of the universe. Sin and death are on the rampage, and like the early Christians we ask, “Who is like the beast, and who can fight against it?” (Revelation 13:4). But even as we utter the question, we know the answer. We have a Savior.

Come, Lord Jesus. Come and save us.

David F. Watson is professor of New Testament and the academic dean at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of Scripture and the Life of God (Seedbed).

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Photo by Ruvim (www.pexels.com).

By W. David O. Taylor

In February 1995, I confessed my sins publicly in front of five hundred fellow students at the University of Texas in Austin. This took place at a concert of prayer sponsored by a parachurch campus ministry. Standing on the auditorium stage of a large classroom, I confessed the sins of lust, pride, impatience, anger, and others I have now forgotten. While I had previously confessed my sins to a pastor or a group of friends, I had never confessed my sins publicly. (It is rather terrifying.) As part of a worship and prayer service, the invitation to confess our sins had offered us a chance to be free from the secrets that distort and oppress us.

Everyone, of course, has a secret of one sort or another. Every family and every community and every country has its secrets too. For some it is an addictive behavior. For others it is an abusive or traumatic experience that may only intensify feelings of shame. For still others it is the fear of being rejected, the lust for power, an uncontrollable temper, emotional infidelity, a vicious prejudice, a program of terror, an insatiable jealousy of others, repeated acts of self-indulgence, or something else.

Whatever they may be, with our secrets we hide. We hide from others and we hide from ourselves. Ultimately, we hide from God. In our hiding, we choose darkness over light; we embrace death instead of life; we elect to be lonely rather than to be relationally at home with others. And the certain result of all our hiding is that we become cut off from our Source of life, strangers to ourselves, and alienated from creation, which, in the end, is pathetic, disfiguring, and an utterly tragic loss of life.

The Psalms understand the human condition. In it we see a mirror of humanity at its best and at its worst. We see our very selves reflected back, “be he a faithful soul or be he a sinner” as Athanasius once described the experience of looking at the psalms, as if in a mirror of the soul. Walter Brueggemann writes that the Psalter “is an articulation of all the secrets of the human heart and the human community, all voiced out loud in speech and in song to God amidst the community.”

If we are to be free, Brueggemann argues, our secrets must be told. If we wish to flourish in our God-given calling, our secrets must be brought into the light so we are no longer governed by their corrosive and destructive power. And if we desire to be truly human, we must abandon all our efforts not just to hide our secrets but also to justify them. This is what the psalms help us to do: to tell our secrets faithfully.

To share our secrets with another person naturally requires a great deal of courage. It requires an ability to trust others in ways that few of us feel safe to do. And to tell our secrets to the community requires an extraordinary ability to believe that it will not take advantage of our vulnerable disclosure – by judging us unfairly, by rejecting us, or by gossiping about us – and that we will not be undone by our confession. To be this brave and to trust this readily is a gift that God would willingly give us, if we but asked.

To be open and unafraid with God in the manner that is modeled for us in the psalms is to counter the devastating effects of our primordial sin. When Adam and Eve sinned, their first impulse was to hide. In making clothes for themselves, they hid their bodies. When they heard the sound of their Maker’s voice, they hid from God. In their telltale lies, they hid from the truth, and in their mutual accusations, they hid from each other. All the ways in which Adam and Eve hid resulted in one thing: their dehumanization.

Like Adam and Eve, when we hide from God, we become alienated from God and thus spend our strength trying to transcend life’s limits: death, dependence, moral laws, God-given boundaries. When we hide from others, we cut ourselves off from the life-giving gift of community. When we hide from creation, we deny our God-ordained creaturely nature and often seek to exploit rather than to care for creation. And when we hide from ourselves, we become strangers to ourselves through selfish, self-indulgent behavior that ultimately does violence to our nature as humans made in God’s image.

What the psalms offer us is a powerful aid to un-hide: to stand honestly before God without fear, to face one another vulnerably without shame, and to encounter life in the world without any of the secrets that would demean and distort our humanity.

The psalms invite us, thus, to stand in the light, to see ourselves truly and to receive the reformative work of God through the formative words of the psalmist, so that we might be rehumanized in Christ.

The honesty of the Psalms. Psalm 139 is the paradigmatic psalm of the honest person. There is nothing the psalmist hides from God. He invites God to see it all. “You have looked deep into my heart, LORD, and you know all about me” (v. 1 CEV). It is a cleansing and healing self-disclosure. To be known by God in this way, through and through, nothing hidden (v. 15), nothing excused (v. 23), is beyond the psalmist’s capacity to fully grasp. “It is more than I can understand,” he says (v. 6 NCV).

It is only in standing open before God in this way, naked like a baby and unashamed as the beloved of God (vv. 13- 16), that the psalmist discovers his truest identity. “I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made” (v. 14). In the psalmist’s waking hours and asleep at night, the Lord is there (vv. 2-3). No height, no depth, not the darkest night, not a secret thought, neither heaven nor hell, can hide the psalmist from the Lord’s searching gaze (vv. 8- 12). He cannot escape the Lord’s presence (v. 7).

Nor does he wish to. The psalmist feels as precious as all the Lord’s thoughts toward him (v. 17). He is secure in the Lord’s sovereign care (v. 16). All the days of his life are seen by God. It is for that reason that the psalmist welcomes the (often terrifying) searching gaze of God. “Investigate my life, O God, find out everything about me; cross-examine and test me, get a clear picture of what I’m about” (v. 23 The Message). This is similar to the language we find in Psalm 17:1-3:

Listen while I build my case, God,

the most honest prayer you’ll ever hear.

Show the world I’m innocent –

in your heart you know I am.

Go ahead, examine me from inside out,

surprise me in the middle of the night –

You’ll find I’m just what I say I am.

My words don’t run loose.

(The Message)

To what end does the psalmist pray in this manner? It is so he might walk in the life-giving “way,” echoing the words of Psalm 1.

To walk in this “way everlasting” is to walk in the way that leads to wholeness. We become whole by praying our honest joys and our honest sorrows. We pray our honest praise of God and our honest anger at God; we pray also for honest speech in our words to God. With the psalmist we pray that God will protect our tongues from deceit (Ps. 34:13). We pray that we not sin with our words (Ps. 39: 1). We pray that we resist the urge to gossip and flatter (Ps. 12:3), and that we choose to live with integrity (Ps. 41:12), rejecting words that both inflate and deflate us before God (Ps. 32).

To pray in this way is to keep ourselves open to others and to God. In refusing the temptation to hide from others and from God, we refuse the temptation to use words as a cover-up. We speak instead plainly, trustingly. When we do this, we find ourselves praying freely to God, in a way that frees us. The Psalter understands that we do not often succeed at this kind of speech and prayer, and so it repeatedly welcomes the penitent to confess to God, in the hearing of God’s people:

Happy are those whose transgression is forgiven,

whose sin is covered.

Happy are those to whom the LORD imputes no iniquity,

and in whose spirit there is no deceit.

(Ps. 32:1-2)

The psalmist describes the experience of “keeping silent” about sin as a kind of disintegration. His bones turn to powder (Ps. 32:3). He risks returning to the dust (Ps. 22:15). But when he honestly confesses his sin, the Lord forgives him. Instead of “covering up” his sin, God covers his sin (Ps. 32:1, 5), and instead of hiding from God, God becomes his “hiding place.”

If honesty is the capacity to speak truthfully to God, sincerely to others, and without any lie about the world in its real condition, then the psalms invite us to honest prayer about all things, not just the things we suffer or regret. We pray honestly about our shame and bouts of depression (Ps. 88). We pray honestly about our hate (Ps.137). And we pray honestly about our experiences of trust and thanksgiving and joy (Pss. 23; 46; 27; 91).

We pray honestly about God’s trustworthy character, the wonder of creation (Ps. 104), the beauty of torah (Ps. 119), and the virtue of wisdom (Pss. 37; 49; 112).

“It is easy to be honest before God with our hallelujahs; it is somewhat more difficult to be honest in our hurts; it is nearly impossible to be honest before God in the dark emotions of our hate,” writes Eugene Peterson in Answering God. “So we commonly suppress our negative emotions (unless, neurotically, we advertise them). Or, when we do express them, we do it far from the presence, or what we think is the presence, of God, ashamed or embarrassed to be seen in these curse-stained bib overalls. But when we pray the psalms, these classic prayers of God’s people, we find that will not do. We must pray who we actually are, not who we think we should be.”

When we pray the psalms by the empowering and transforming presence of the Holy Spirit, we pray not just who we actually are but also who we can be and shall be by grace. As Athanasius sees it, the psalms not only enable us to be wholly ourselves before God, they also enable us to be wholly our true selves. This is only possible, he argues, because Christ himself makes it possible. Before coming among us, Athanasius writes, Christ sketched the likeness of true humanity for us in the psalms. In praying them, then, we experience the healing and reformation of our humanity.

The good news for the follower of Jesus is that the decision to be honest to God, which the psalms require of us, does not result in self absorption because we have become obsessed with the cross examination of our heart and mind. Nor does it result in self-hatred because we feel that our sin has the last and most definitive word on our life. Grace has the last word, not sin, as the German theologian Karl Barth rightly reminds us. No matter how great our fault or failure, we cannot sin apart from the grace of God.

“We are forbidden,” Barth writes, “to take sin more seriously than grace, or even as seriously as grace.” Why? Because God in Christ does not take sin more seriously than grace, even if it remains true that God takes sin with deadly seriousness. We can be honest to God about the best and worst parts of our human condition, because we know that the grace of God precedes our honest confessions, the grace of God undergirds our honest thanksgivings, and the grace of God follows our honest laments.

What happens when we pray the psalms under the light of God’s grace? We become free to pray with abandonment because we have abandoned ourselves to this gracious God. We have no need to hide from this God, because we are so confident in his grace. And because Jesus comes to us “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14), we can be confident that we shall be found and filled with grace. We, too, can pray daring prayers because we trust that Jesus himself prays them with us and in us by the power of his Holy Spirit.

Expressing all the emotions. To this day I regret that I failed to keep the piece of paper on which I had written the eleven sins I had originally confessed to both friends and strangers at the University of Texas. I also regret the failure of courage that I experience repeatedly in my resistance to honestly confess my faults. It is for that reason that I return again and again to the psalms. The psalms show me how to be honest to God. They retrain me to be honest with God’s people, and they remind me how deeply good it feels to be this open, unafraid, and free.

“The Psalms are inexhaustible, and deserve to be read, said, sung, chanted, whispered, learned by heart, and even shouted from the rooftops,” observes N.T. Wright. “They express all the emotions we are ever likely to feel (including some we hope we may not), and they lay them, raw and open, in the presence of God.”

The psalms welcome all such honest speech in order that we might encounter the “life that really is life” (1 Timothy 6:19). If the common saying within recovery ministries is true, that we are only as sick as the secrets we keep, then the secrets we keep result in the deterioration of our humanity. Kept hidden, our secrets rob us of vitality. But when they are brought into the gracious light of God, they no longer hold a destructive power over us, and a space is made for God, who “knows the secrets of the heart,” to rehumanize us (Ps. 44:21).

One of the great benefits of the psalms, Athanasius believed, is that in reading them “you learn about yourself.” You see all your failures and recoveries, all your ups and downs. You see yourself as both a saint and a sinner. But the psalms are not only interested in helping us to be open and unafraid before God; they also help us to be open and unafraid with the people of God: vulnerable, porous, freed, fully alive. And in seeing ourselves in this way, honestly, with others, we find ourselves being reformed by the love of God.

W. David O. Taylor is assistant professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary and director of Brehm Texas, an intuitive in worship, theology, and the arts. Taken from Open and Unafraid: The Psalms as a Guide to Life by W. David O. Taylor. Copyright © 2020 by David Taylor. Used by permission of Thomas Nelson. (www.openandunafraid.com).

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

In December of 1784, Thomas Coke, Richard Whatcoat, and Thomas Vasey met with preachers of the American “connexion” for a constitutional convention at Lovely Lane Chapel in Baltimore. Dubbed the “Christmas Conference,” Francis Asbury was ordained as co-superintendent. Painting by Thomas Coke Ruckle, The Ordination of Bishop Asbury, engraved by A. Gilchrist Campbell (1882).

By Thomas Lambrecht –

“Conferencing” is at the heart of Methodist history and tradition. In 1744, only a few years after starting the Methodist movement, John Wesley called together the small group of preachers who formed the core of the movement for a “conference” meeting. They gathered to discern “how we should proceed to save our own souls and those that heard us.” Their agenda was simple, but comprehensive: “1. What to teach, 2. How to teach, and 3. What to do, that is, how to regulate our doctrine, discipline, and practice.”

Ever since, the “conference” has been part and parcel of how Methodists do church. The 1744 conference became an annual affair, a gathering of all the preachers (lay and clergy) who were “in connexion” with John Wesley. Thus, the “annual conference” became the center of Methodist organization. As the church was formed in America and grew, the number of annual conferences multiplied, covering different geographical parts of the country, and later, of the world. Each annual conference formed a geographical section of the general church. To maintain unity, a General Conference consisted of representatives from all the various annual conferences, making decisions on behalf of the whole church. When the church was broken up into regions in 1939, those bodies were called jurisdictional conferences and later central conferences (i.e., jurisdictions outside the U.S.), for the purpose of electing and assigning bishops. Within each annual conference, there are sub-regions called districts that have a “district conference.” And of course the basic building block of the denomination is the local “church conference” or “charge conference.”

Conferences are far more than geographical organizational units. They represent the intuitive genius of Wesley’s organizational mind that identified collective decision-making as an essential component of church structure. Many Protestant denominations in Wesley’s time were governed by irregularly meeting synods or councils that would gather only when necessary. Wesley saw the strength to be gained by collective decision-making by a body of people that is held in constant relationship and mutual accountability.

The idea of collective decision-making was instituted early in the Church’s history, at the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15), which was called to decide whether Gentile converts must be circumcised and required to follow the Law of Moses. Such collective decision-making allows the Holy Spirit to speak through the diversity of voices who are part of the collective. Reaching agreement among a broad group of leaders often results in a more faithful decision and one that is able to consider more of the ramifications of that decision. It has the added benefit of gaining “buy-in” from the same group of leaders that will have to implement the decisions that are made.

The Wesleyan Covenant Association (WCA) has just released Part Seven of its draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline, addressing the role of annual, regional, and general conferences in a new global traditional Methodist denomination. Additional provisions about conferences may be found in the proposed Constitution, ¶203, Articles VI-VIII, that can be found on the WCA website (www.wesleyancovenant.org).

As the WCA considered the wisdom of retaining our conferencing system of decision-making and organization, we also realized the current United Methodist system had strayed off the path in a number of ways that need to be corrected if Methodism is to recover its vitality.

First, the UM system has reversed the hierarchy in an unhelpful way. The annual conference and General Conference were instituted as means to support and empower the work of the local church, which is (we say) “the most significant arena through which disciple-making occurs.” Instead, in recent years, it seems like the local church has existed to support the work of the annual and General Conference. In its reformation of the conference system, the WCA strives to make crystal clear that conferences exist to support the local church, not the other way around.

Second, and relatedly, the annual and General Conferences have grown too large in structure and demand too many resources. The “needs” of ministry at the regional and global levels siphon off too much time and financial resources from local churches, which then weakens the local ministry rather than strengthens it. This is seen in the amount of time pastors spend on annual conference business outside their parish and bishops spend on global church business outside their annual conferences. Many local churches do not see the value to them of the work that annual conference and general church agencies do “on their behalf.”

Accordingly, the WCA’s proposal calls for a lean annual conference structure demanding lower apportionments and less time investment in bureaucracy and meetings, with more time and financial investment in work that explicitly supports the ministry of local churches, including the aggressive planting of new congregations. Bishops and district superintendents are relieved of many of their administrative responsibilities and expected to focus their time and energy within their districts and annual conferences, while still building connections to the worldwide church based on mutual ministry, rather than meetings (see Part Six of the draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline on the WCA website.)

The general church would have only five agencies (called “commissions”) to handle the coordinating and facilitating work of the denomination. (More details on these commissions are found in Part Eight of the WCA’s draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline which has just been released.) The annual conference would have only four required boards or committees to facilitate its work. (It could form more as needed.) The emphasis is really on reducing the amount of structure and reorienting the work of the annual conference and general church to support the local church’s ministry.

Third, as the church has grown over the last 100 years, its Book of Discipline has gotten too prescriptive and controlling, with all kinds of mandates and requirements that often hamper the work of the local church. The current Discipline is 819 pages (not including the index). I have a 1926 Discipline that is only half that size and includes worship rituals, judicial decisions, a description of the course of study, and a directory!

Accordingly, the WCA proposal allows annual conferences to structure themselves in a way that makes sense for them, aside from the minimal requirements for four agencies. This will allow conferences to stay lean in structure, yet nimble enough to adapt to changing circumstances. It will also allow for cultural differences in various parts of the world to be reflected in variations of structure and process. At the same time, nearly all the provisions in the draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline would meet the needs and requirements in conferences around the world. The WCA has worked to craft a book that would apply equally well in Bulgaria, the Philippines, the U.S., or Zimbabwe. This will allow for greater uniformity on the essential matters, while allowing flexibility in many other matters.

Finally, in an effort to take the focus of the church off of the (sometimes contentious) General Conference, the WCA proposal in ¶ 203 (Article VI) of the draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline, envisions General Conference meeting only once every six years, instead of quadrennially. For the first six years, it would meet every two years in order to fine tune the general church’s core teachings and governance structure as we live into a new reality. But thereafter, General Conference will be reserved for making the larger policy decisions and letting annual conferences and local churches focus on their ministry.

The WCA’s proposals are just that – proposals. They will be presented as legislation to the convening conference of a new global traditional Methodist church. We hope you will consider them and give constructive feedback as we compile ideas to guide the formation of a new Methodist denomination that focuses both on biblical faithfulness and on ministry effectiveness and fruitfulness.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”