by Steve | May 15, 2018 | May/June 2018

Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

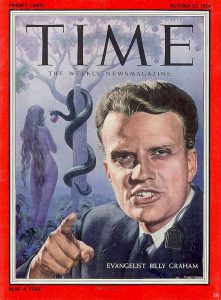

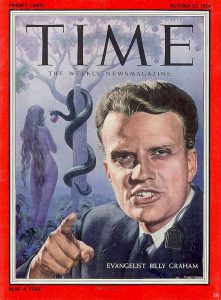

Into the Arms of Eternity: Remembering Billy Graham

By Steve Beard –

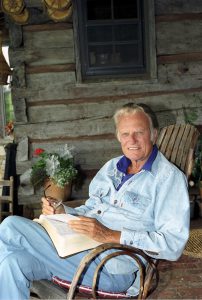

Wherever he landed around the globe, Billy Graham spent his life preaching a simple and sincere message of God’s love for all people, the urgent need for conversion, and the assurance that Jesus Christ walks with believers in the brightest and darkest of times. Throughout his illustrious ministry, Graham preached to nearly 215 million people in more than 185 countries and territories via his simulcasts and rallies. His audience exposure leaps exponentially when television, newspaper columns, videos, magazine stories, webcasts, and best-selling books are factored in.

Illustrative of his technological wizardry, Graham once spearheaded an event more than two decades ago that astonishingly utilized 30 satellites broadcasting taped evangelistic messages from Graham in 116 languages to 185 countries.

The news of his death on February 21 at his home in Montreat, North Carolina, at the age of 99, was observed with both joy and sorrow. The lanky world-renowned evangelist was buried in a rudimentary pine plywood coffin made by men convicted of murder from the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

For Christians, Graham was a role model in holding firm to both evangelism and integrated social action, orthodoxy and generous ecumenism, grace and truth, love and repentance. In addition to preaching his life-transforming message, he was pivotal in helping form numerous evangelical institutions that will be remembered as part of his fruitful legacy.

“Billy Graham was a man with beautiful integrity, clothed with humility, and combined with a sterling message of the gospel,” Dr. Robert Coleman, author of The Master Plan of Evangelism, told Good News. Coleman was a close friend and associate of Graham for 60 years, leading the Institute of Evangelism in the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College and serving as Dean of the Billy Graham International Schools of Evangelism. Coleman was one of a handful of United Methodists who attended Graham’s funeral along with Drs. Eddie Fox, Maxie Dunnam, and Timothy Tennent.

“Wherever we traveled around the world, Billy was a master of making a nobody feel like a somebody,” Coleman recalled. “You always felt lifted up in his presence. Whether you were a street sweeper or a king, Billy saw you as someone deeply loved and treasured by God.”

Although most well known as a Baptist, Graham had a special relationship with Methodists dating back to his early friendship with lay evangelist Harry Denman, a man Graham described as “one of the great mentors for evangelism in my own life and ministry – and for countless others in evangelism as well.” Denman, who died in 1976, was the leader of the Commission on Evangelism of the Methodist Church. In the forward to the book Prophetic Evangelist, Graham wrote: “I never knew a man who encouraged more people in the field of evangelism than Harry Denman.”

Methodist Bishop Gerald Kennedy’s position as chairman of the Billy Graham rally in Los Angeles in 1963 caused a controversial stir among fundamentalists and others who did not see a place for mainline denominations in Graham’s evangelistic efforts. In the premier issue of Good News in 1967, Kennedy wrote that he had hoped his position would be an opportunity to bring conservative evangelicals and mainline churches closer together. “We never succeeded at eliminating all our differences,” he wrote, “but we did make progress in talking to one another and trying to listen to each other with some appreciation.”

Over the decades, United Methodists were inspired by Graham’s message, temperament, and integrity. “No voice in the past half-century has been more powerful and faithful in pointing clearly to Jesus Christ than the message of Billy Graham,” Dr. Eddie Fox, former World Director of World Methodist Evangelism, said. “His message always led persons to Jesus Christ.” Fox was a speaker at several of the Billy Graham Schools of Evangelism.

According to United Methodist News Service, the late Bishop Leontine Kelly, who headed the evangelism unit of the denomination’s Board of Discipleship before her election to the episcopacy in 1984, characterized Graham’s preaching as “electric.” “His purposes were clear and his commitment to Jesus Christ was unwavering,” said Kelly, who died in 2012. “We will always be grateful for television, which enabled his communication of the gospel of Jesus Christ to millions.”

Graham had unparalleled reach. A 2005 Gallup poll revealed that 16 percent of Americans had heard Graham in person, 52 percent had heard him on radio, and 85 percent had seen him on television.

“Only the large expressive hands seem suited to a titan,” biographer William Martin, author of A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story, observed. “But crowning this spindly frame is that most distinctive of heads, with the profile for which God created granite, the perpetual glowing tan, the flowing hair, the towering forehead, the square jaw, the eagle’s brow and eyes, and the warm smile that has melted hearts, tamed opposition, and subdued skeptics on six continents.”

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

In hindsight, Graham registered his regret for not participating in civil rights demonstrations. “I think I made a mistake when I didn’t go to Selma, [Alabama in 1965],” Graham confessed to the Associated Press in 2005. “I would like to have done more.” It has been properly noted that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. considered Graham an ally. “Had it not been for the ministry of my good friend Dr. Billy Graham, my work in the Civil Rights Movement would not have been as successful as it has been,” said King. Other African American leaders, however, regret that Graham was not more front-and-center in the struggle.

“Graham clearly felt an obligation to speak against segregation, but he also believed his first duty was to appeal to as many people as possible. Sometimes he found these two convictions difficult to reconcile,” Martin wrote in A Prophet with Honor.

Close proximity to the corridors of political power – especially the Nixon White House – occasionally blindsided Graham. When asked in 2011 by Christianity Today, a magazine he helped launch, if there was anything he would have done differently, Graham responded: “I would have steered clear of politics. I’m grateful for the opportunities God gave me to minister to people in high places; people in power have spiritual and personal needs like everyone else, and often they have no one to talk to. But looking back I know I sometimes crossed the line, and I wouldn’t do that now.”

Of his regrets, those closest to home were the most sensitive. “Ruth says those of us who were off traveling missed the best part of our lives – enjoying the children as they grew. She is probably right. I was too busy preaching all over the world.” Ruth Bell married Graham in 1945 and the couple had five children. “I came through those years much the poorer psychologically and emotionally,” he reflected. “I missed so much by not being home to see the children grow and develop.”

Graham questioned some of the aspects of his jet-setting ministry. “Sometimes we flitted from one part of the country to another, even from one continent to another, in the course of only a few days,” he recalled. “Were all those engagements necessary? Was I as discerning as I might have been about which ones to take and which to turn down? I doubt it. Every day I was absent from my family is gone forever.”

Johnny Cash and Billy Graham. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Although Graham never had regrets about committing his life to preaching a Christian message, he wished he would have spent more time in nurturing his own personal spiritual life. “I would spend more time in prayer, not just for myself but for others,” he said. “I would spend more time studying the Bible and meditating on its truth, not only for sermon preparation but to apply its message to my life. It is far too easy for someone in my position to read the Bible only with an eye on a future sermon, overlooking the message God has for me through its pages.”

Boxing champion Muhammad Ali meets with Ruth and Billy Graham at their North Carolina home. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

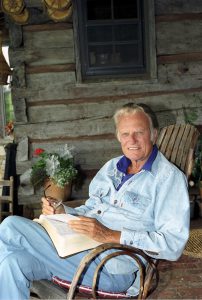

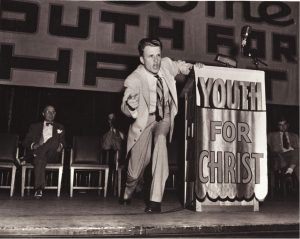

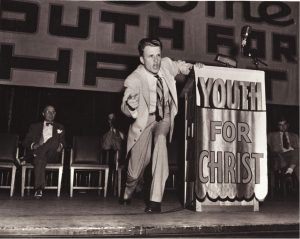

“He brought down the storm.” Three years ago, Bob Dylan called Graham the “greatest preacher and evangelist of my time — that guy could save souls and did.” The music icon testified in AARP The Magazine to having attended some Graham rallies in the 1950s and ‘60s and described them in a distinctly Dylanesque way: “This guy was like rock ’n’ roll personified – volatile, explosive. He had the hair, the tone, the elocution – when he spoke, he brought the storm down. Clouds parted. Souls got saved … If you ever went to a Billy Graham rally back then, you were changed forever. There’s never been a preacher like him. … I saw Billy Graham in the flesh and heard him loud and clear.”

U2 lead singer Bono wrote a poem for the Grahams. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Although he is most well-known for his relationships with politicians, straight-and-narrow Graham was best of friends with Johnny Cash, the blue-collar troubadour who, when they met in 1969, was making headlines for recording live albums in Folsom State and San Quentin prisons. The Grahams and Cashs grew to be very close. Not only did Johnny and June Cash perform at Graham rallies, but Billy and Ruth joined the Cash family on numerous vacation outings.

“I’ve always been able to share my secrets and problems with Billy, and I’ve benefited greatly from his support and advice,” Cash wrote in his autobiography. “Even during my worst times, when I’ve fallen back into using pills of one sort or another, he’s maintained his friendship with me and given me his ear and advice, always based solidly on the Bible. He’s never pressed me when I’ve been in trouble; he’s waited for me to reveal myself, and then he’s helped me as much as he can.”

Despite what some perceived as a squeaky-clean piety that gravitated to the halls of power, Graham had a deep and abiding love for the outsiders and the spiritual searchers. “It was eleven o’clock on a Sunday morning, but I was most definitely not in church,” Graham wrote in his autobiography Just As I Am. “Instead, to the horror of some, I was attending the 1969 Miami Rock Music Festival.” Preaching from the same concert stage as Canned Heat, the Grateful Dead, and Santana, Graham wrote about his delight to speak to “young people who probably would have felt uncomfortable in the average church, and yet whose searching questions about life and sharp protests against society’s values echoed from almost every song.”

Graham actually donned a disguise to get a feel for the festival the night before he would preach. “My heart went out to them,” he wrote. “Though I was thankful for their youthful exuberance, I was burdened by their spiritual searching and emptiness.”

Although Graham was prepared to be “shouted down,” he was “greeted with scattered applause. Most listened politely as I spoke.” He told them that he had been listening carefully to their music: “We reject your materialism, it seemed to proclaim, and we want something of the soul.” Graham proclaimed that “Jesus was a nonconformist” and the he could “fill their souls and give them meaning and purpose in life.” As they waited for the upcoming bands, Graham’s message was, “Tune in to God today, and let Him give you faith. Turn on to His power.”

Graham’s well-known message also did not hinder his ability to reach beyond evangelical boundaries. He longed for improved relationships between Roman Catholics and Protestants and was a trusted friend of Catholic television pioneer Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. “We are brothers,” Pope John Paul II told Graham during a visit to the Vatican.

In 1979, the late Muhammad Ali, three-time world heavyweight boxing champion, spent several hours with Graham in the evangelist’s home in North Carolina. “When I arrived at the airport, Mr. Graham himself was waiting for me. I expected to be chauffeured in a Rolls Royce or at least a Mercedes, but we got in his Oldsmobile and he drove it himself,” Ali recalled. “I couldn’t believe he came to the airport driving his own car. When we approached his home I thought he would live on a thousand acre farm and we drove up to his house made of logs. No mansion with crystal chandeliers and gold carpets, it was the kind of house a man of God would live in. I look up to him.”

Ali told the press, “I’ve always admired Mr. Graham, I’m a Muslim and he’s a Christian, but there is so much truth in the message he gives, Americanism, repentance, things about government and country – and truth. I always said if I was a Christian, I’d want to be a Christian like him.”

Generations later, Graham’s magnetism never weakened. One month after the Irish band U2 played an unforgettably emotional halftime show at the Super Bowl in 2002 memorializing the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Bono responded to an invitation to visit the Grahams at their home. Inside a collection of the work of Irish poet Seamus Heaney given to Ruth and Billy, Bono had written a poem that refers to “the voice of a preacher/loudly soft on my tears” which was the “lyric voice that gave my life/A Rhyme/a meaning that wasn’t there before.” The poem is on display at the Billy Graham Library in North Carolina.

In a touching tribute to Graham three years later, Bono said: “At a time when religion seems so often to get in the way of God’s work with its shopping mall sales pitch and its bumper sticker reductionism, I give thanks just for the sanity of Billy Graham – for that clear empathetic voice of his in that southern accent, part poet, part preacher – a singer of the human spirit, I’d say. Ah, yeah I give thanks for Billy Graham.”

Billy Graham preaches in the 1950s. Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Evangelistic energy. In addition to calling men, women, and children – rich and poor, black and white, powerful and humble – all over the globe to a commitment to Christ, Graham was also reminding the institutional church of the foundational need to share the faith. In 1976, his efforts were recognized by the United Methodist Association of Evangelists as one of the earliest recipients of the Philip Award. Four years later, he preached at the denomination’s Congress on Evangelism on the campus of Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“Many have moved from a belief in man’s personal responsibility before God to an entirely new concept that assumes all men and women are already saved,” said Graham in 1980. “There’s a spreading universalism, which has deadened our urgency that was had by John and Charles Wesley, Francis Asbury, E. Stanley Jones, and others like them.

“This new evangelism leads many to reject the idea of conversion in its historical Biblical meaning and the meaning historically held and preached and taught by the Methodist Church.”

Graham concluded his remarks by quoting Methodist leader John Wesley in 1784: “You have nothing to do but to save souls, therefore spend and be spent in this work.” He continued to quote Wesley, “It is not your business to preach so many times and to take care of this or that society; but to save as many souls as you can; to bring as many sinners as you possibly can to repentance and with all your power to build them up in that holiness, without which they will never see the Lord.”

Graham reminded the participants of their heritage. “Let it be remembered that the Methodist church began in the white peak of conversion and intense evangelistic energy,” he said. “Let it be recalled that the Methodist church is an evangelistic movement.”

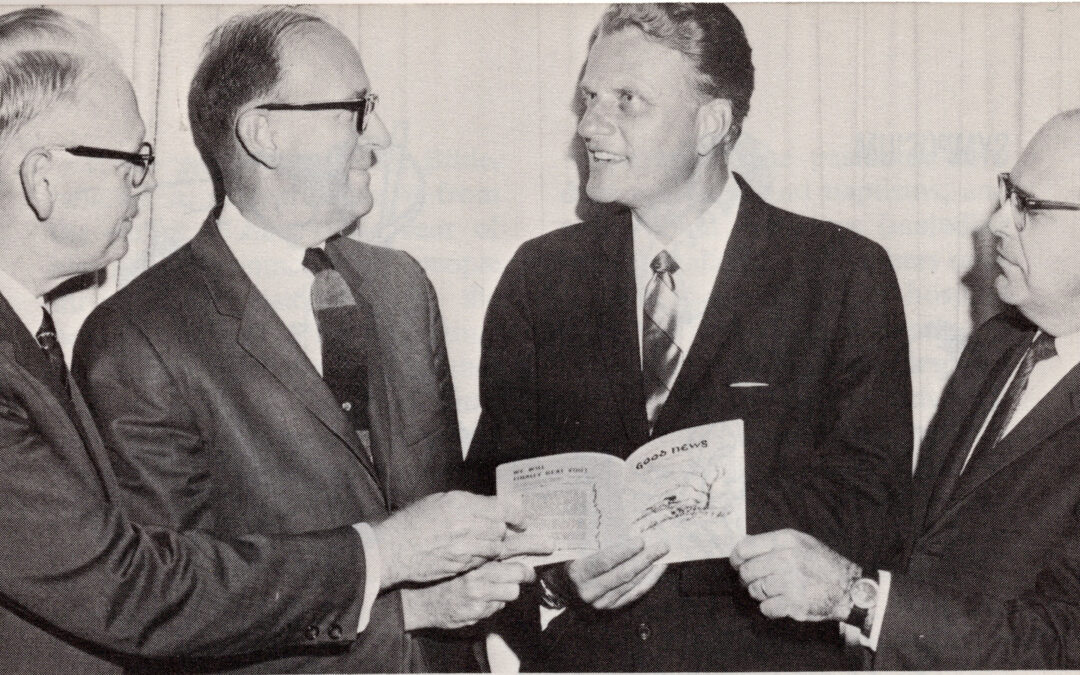

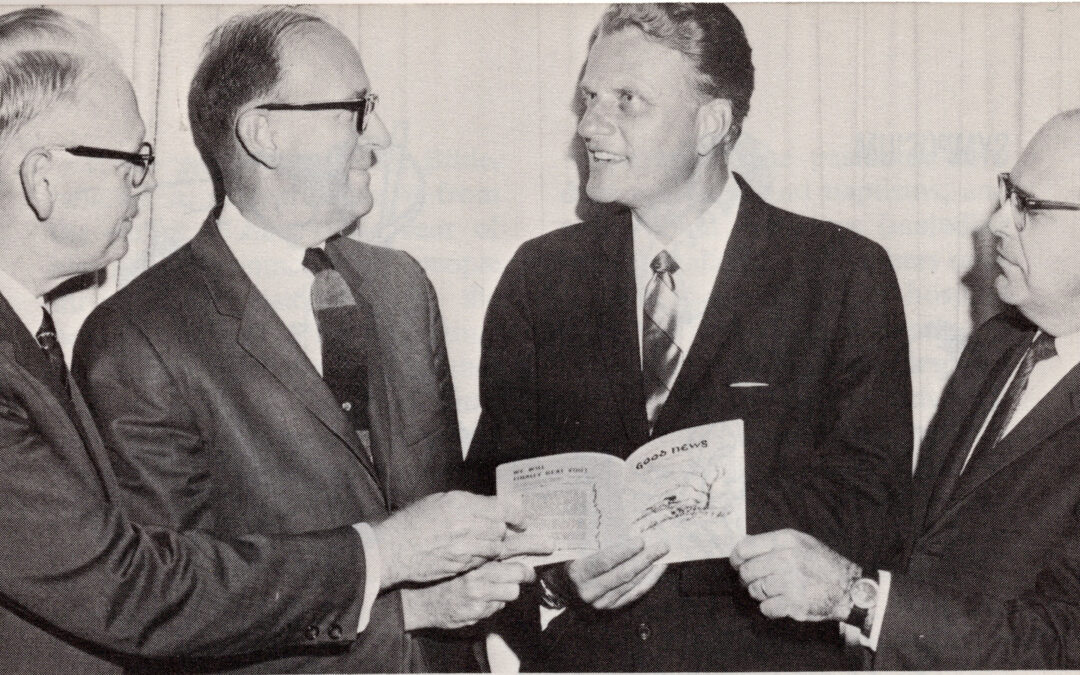

Good News connection. More than a decade before his address at the Congress on Evangelism, Graham’s preaching played a key role in the conversion of Good News’ founding editor Charles Keysor. The evangelist’s encouragement was also an important inspiration during the ministry’s formative years.

“I have always believed that The United Methodist Church offers tremendous potential as a starting place for a great revival of Biblical Christian faith,” Graham wrote in a personal note of encouragement to the staff and board of directors on the occasion of the 10-year anniversary of Good News. “Around the world, millions of people do not know Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord, and I believe that The United Methodist Church, with its great size and its honorable evangelistic tradition, can be mightily used by God for reaching these lost millions,” wrote Graham in 1977.

“I have been acquainted with the Good News movement and some of its leaders since 1967. To me it represents one of the encouraging signs for the church fulfilling its evangelistic mission, under the Bible’s authority and the leadership of the Holy Spirit. At the forefront of the Good News movement has been Good News magazine. For 10 years it has spoken clearly and prophetically for Scriptural Christianity and renewal in the church. It should be read by every United Methodist.”

Everyone associated with Good News in that era – and subsequent generations – found great inspiration in Graham’s words.

The message and the man. “Billy Graham’s ministry taught me to step out in faith and trust God in all things in my life,” Dr. Timothy C. Tennent, president of Asbury Theological Seminary, said in a statement after attending Graham’s funeral in North Carolina.

“After preaching in Red Square in what was then the Soviet Union, Billy Graham stopped at Gordon Conwell, where I was a student. Someone asked Mr. Graham if he had been used as part of Soviet propaganda. He replied that he had preached the same Gospel in Red Square as he did around the world. This taught me not to worry about the discouraging naysayers and critics in my ministry. Even Billy Graham’s funeral continued to teach us about the grace and glory of God.”

There was one testimony of poignant grace at Graham’s funeral that caught the attention of the Rev. Dr. Maxie Dunnam, former World Editor of The Upper Room and evangelical United Methodist leader. “The most meaningful for me was the sharing of one daughter who had a painful marriage that ended in divorce,” he recalled. “She spoke about her shame and how dreadful it was to think of how this was affecting her Mom and Dad, but how redemptive it was when she was welcomed home by Billy with open arms.”

“It was a powerful prodigal daughter story. There was no pretension of perfection,” Dunnam said. “The feeling was that we were at a large family funeral, friends gathered to remember, to share their grief and celebrate the life of a loved one. Again, the emphasis was not on the man but the message.”

When speaking about the end of his own life, Graham used to like to paraphrase the words of one of his heroes, D. L. Moody, an evangelist of a different era: “Someday you will read or hear that Billy Graham is dead. Don’t you believe a word of it. I shall be more alive than I am now. I will just have changed my address. I will have gone into the presence of God.”

Graham’s admirers note the change of address with deep respect and love.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Opening photo: Billy Graham discusses the second issue of Good News with (left to right) Dr. Frank Stanger, president of Asbury Theological Seminary; the Rev. Philip Worth, United Methodist pastor and chairman of the Good News board of directors; and Dr. Charles Keysor, founder of Good News.

by Good News | Jul 23, 2010 | Magazine Articles

Elliot Wright

Can Methodists learn anything about effective Christian evangelism from their denomination’s founding period 250 years ago?

“Yes,” says a Duke University professor, who told 600 church developers how the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, gave rise to a movement that swept the young United States of America.

“Early Methodism was evangelistic,” the Rev. Laceye Warner (pictured right) explained to the 2009 United Methodist School of Congregational Development in July. “When the Wesleys talked about spreading ‘Scriptural holiness,’ they meant evangelism.” She defined evangelism as preaching the gospel of salvation in Jesus Christ and “living it out.”

One of the recurring themes at successive annual Schools of Congregational Development, which are sponsored by the United Methodist Boards of Discipleship and Global Ministries, is the decline in Methodist membership in the United States (and also in Britain, where it originated). Mission-founded expressions of the denomination found elsewhere are growing.

Reclaiming strengths. Numbers alone are not all that matters, said Warner, who holds a chair of evangelism at Duke Divinity School in Durham, North Carolina.

Among the qualities of early Methodism that could help the contemporary church reclaim its earlier strengths is the idea that growth in grace is as important as growth in numbers. Other relevant qualities are the beliefs that theological reflection is essential, sustained Christian practices maintain the community of faith, and wealth and material goods are meant to be shared.

The building blocks for the early Methodist movement included “classes” and “bands” that developed after people responded to Methodist preaching, often set in open fields and other public spaces, rather than in church buildings.

Classes were groups of 10 to 12 people organized by geographic location—neighborhoods—while bands were 6 to 8 people who voluntarily came together for spiritual nurture. There were two kinds of bands: “select” and “penitential” or “over-achievers” and “backsliders.” But, when the lists of band members are examined, those who show up on the “select” list were once themselves among the “penitential,” Warner said.

“The experience of sanctification was expected to take place in small groups,” she continued, “but it didn’t happen for all at the same pace. We have one record of it taking someone 48 years to experience sanctification.” Growth in grace, Warner said, was as important to the Wesleys as expanding membership rolls. The growth was steady but gradual.

People fed one another spiritually in the early Methodist movement; they kept personal journals that were shared. Not everyone stayed with the spiritual and social “discipline” that the Wesleys taught and practiced. Scriptural and “social holiness” were partners in the Wesleyan movement. Warner indicated that membership loss started at the very beginning among those who did not share the vision.

By Elliot Wright, information officer of the United Methodist Board of Global Ministries. This article was distributed by United Methodist News Service.

by Good News | Jul 23, 2010 | Magazine Articles

By Kenneth C. Kinghorn

John Wesley invented no new theological doctrines. “Whatever doctrine is new must be wrong,” he wrote, “and no doctrine can be right, unless it is the very same ‘which was from the beginning.’” Mr. Wesley said, “If Methodism…be a new discovery in religion…this [notion] is a grievous mistake; we pretend no such thing.” Far from being narrowly sectarian, John Wesley was a catholic Christian. He stood firmly in the mainstream of historic Christianity, and drew from many of the tributaries that fed into it.

1. Early Church Writers. John Wesley often referred to “Primitive Christianity,” that is, the Church from the end of the apostolic age to the early fourth century. Christian writers in this era helped confirm the biblical canon, the doctrine of the Trinity, and the mystery of the Incarnation, through which the eternal Christ entered time and space as fully human and fully God. Mr. Wesley said of those early, “primitive” Christians, “I reverence their writings, because they describe true, genuine Christianity….They never relinquish this: ‘What the Scripture promises, I enjoy. That the God of power and love may make you, and me, such Christians as those Fathers were, is [my] earnest prayer.’”

2. The Protestant Reformation. John Wesley was a Protestant, who believed the Medieval Church had allowed layers of nonbiblical tradition to cloud the gospel of grace. Accumulated ecclesiastical inventions compelled the sixteenth-century Reformation. The Wesleyan message harmonizes with the fundamental themes of the Protestant Reformers, who recovered the supremacy of Scripture above human conventions. The essence of Protestantism is that salvation comes through grace alone, faith alone, and Christ alone. Wesley wrote, “We have all reason to expect…that [Christ] should come unto us quickly, and remove our candlestick out of its place, except we repent and…unless we return to the principles of the Reformation, the truth and simplicity of the gospel.”

3. Pietism. The Wesleyan tradition also borrows from the seventeenth-century German Pietists. Those earnest Christians championed the individual’s personal knowledge of Christ, serious discipleship, Christian witness, missions, and social ministries. Wesley referred to the Pietist August Francke as one “whose name is indeed as precious ointment. O may I follow him, as he did Christ!” From the Moravian Pietists, the early Wesleyan movement appropriated such means of grace as class meetings, conferences, vigils, and Love-feasts.

4. The Mystics. The influence of certain aspects of mysticism further reveals the catholicity of the Wesleyan message. John Wesley’s reading of Thomas à Kempis led him first to see that “true religion was seated in the heart, and that God’s law extended to all our thoughts as well as our words and actions.” Jeremy Taylor’s Rule and Exercises of Holy Living (1650) and Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying (1651) and William Law’s Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728) convinced Wesley of “the exceeding height and depth and breadth of…God.” The mystics also helped Wesley understand the Christian’s privilege of knowing the inner witness of the Holy Spirit. He wrote, “The light flowed in so mightily upon my soul, that everything appeared in a new view….I was persuaded that I should be accepted of Him, and that I was even then in a state of salvation.”

5. The Puritans. The Wesleyan message also bears the influence of the Puritan divines, such as John Owen, Thomas Goodwin, and Richard Baxter. These prodigious writers highlighted the profound depths of grace, God’s call to purity, and living daily in the light of eternity. “Their judgment is generally deep and strong,” said John Wesley, “their sentiments just and clear, and their tracts on every head full and comprehensive, exhausting the subjects on which they write…. They are men mighty in the Scriptures, equal to any of those who went before them, and far superior to most that have followed them.”

The power of the Wesleyan witness. All valid Christian traditions preach that justification and adoption give repentant sinners a new standing, in which God imputes Christ’s righteousness to us and frees us from the guilt of sin. The Wesleyan message also emphasizes that regeneration and sanctification give us a new state, in which God imparts Christ’s righteousness to us and frees us from the power of sin.

The sources and treasures of the Wesleyan message have never been more relevant than today.

Kenneth C. Kinghorn has taught Methodist history for more than 43 years at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. He is the author of many books including The Heritage of American Methodism and the three volume set of John Wesley’s Standard Sermons in Modern English.

by Good News | Jul 23, 2010 | Magazine Articles

By James V. Heidinger II

In my retirement, there has been a welcome change of pace. In the midst of several major family projects, it has been refreshing to have time to do a lot of reading.

One of the big serendipities this fall has been working through Basic United Methodist Beliefs: An Evangelical View with the Sunday school class that I teach at First United Methodist Church in Lexington, Kentucky. First published by Good News in 1986, it is now published by Bristol House, Ltd.—the original Good News fledgling publishing venture that we sold to a small group of supporters/board members in 1991. Since then, it has become a strong and impressive for-profit organization in offering excellent ministry resources for United Methodists and beyond.

Basic United Methodist Beliefs actually came from a series of articles on Wesleyan theological distinctives that began in the March/April 1983 issue of Good News magazine. Our goal was to help clarify what United Methodists believe. It was our hope that readers would rediscover John Wesley in a fresh and contemporary way. The magazine series also coincided with the approaching bicentennial celebration of Methodism in America (1984), which we felt would bring a resurgence of interest in Methodist theology.

Early this fall, I received the shipment of books for my class and was looking through the volume once again, seeing familiar names of contributors I hadn’t thought about for some time—UM leaders and teachers including Bishop Mack B. Stokes, Frank Baker, Dennis Kinlaw, Steve Harper, Riley Case, Frank Stanger, Robert Tuttle, Joel Green, Paul Mickey, and others.

21st printing.

Then came the serendipity: as my eyes moved from the table of contents page to the copyright page, I was astonished to see that the volume I was holding represented the 21st printing of the book! I was stunned and a bit overwhelmed. This small volume, with 13 chapters summarizing our basic Wesleyan doctrinal beliefs, was in its 21st printing and sported an attractive new cover design. After 23 years, it is obviously alive and well and still enjoying a robust readership. Praise God!

As I was leafing through this new edition, I discovered something else I had forgotten. As an appendix, we had included the full text of “The Junaluska Affirmation,” a sound and well-crafted statement of scriptural Christianity adopted by the Good News Board of Directors in 1975. It was a response to the new doctrinal statement adopted by the 1972 General Conference—one that challenged all members “to accept the challenge of responsible theological reflection.”

In a day of theological confusion, the Junaluska Affirmation brought a refreshing clarity to the church’s theological discussion. In 1980, Paul Mickey, who had chaired the Task Force that produced the Affirmation, wrote Essentials of Wesleyan Theology, a rich, in-depth commentary on the Affirmation.

The mood of the era. As I looked at the first chapter of the book, Dennis Kinlaw’s “Let’s Rediscover Wesley for Our Time,” I found myself reflecting on the mood of the United Methodist Church back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Kinlaw recalled a United Methodist pastor who had surprised him with the comment that “he could envision few prospects more dismal to him than a return by the church to the theology of its founder.”

Such a sentiment may sound strange today. However, for many of us associated with Good News back then, we longed for a rediscovery of Wesley’s scriptural Christianity and a return to the rich Wesleyan doctrinal distinctives.

The sad fact is that during those years, Wesley’s theology and evangelical passion were less than popular and often negatively caricatured. Rather than hearing much about Wesleyan doctrine, United Methodists were subjected to vacuous fad theologies that would come and go like seasonal colors, often accompanied by the admonition we must remember we’re a church that embraces “theological pluralism.” This left many mainline observers concluding in those days that one could be a United Methodist and believe about anything you wanted to believe. It also left us evangelicals deeply dissatisfied.

“It may well be that the current stagnant state of the church is not due to the fact that the old truths are no longer relevant,” wrote Kinlaw. “In my own travels I have observed that the old truths are unknown.”

Could it be that the denomination that boasts of Wesley as its founder reared a generation uninstructed in what he taught and believed? Sadly, during this era of turbulence and secularization, the rich and tested Wesleyan theologies of William Cannon, Colin Williams, Philip Watson, Albert Outler, and others were neglected or put aside for newer but less biblical—and certainly less Wesleyan—theologies.

Are we rediscovering Wesley? As I reflected on Kinlaw’s essay on rediscovering Wesley, I found myself thinking that this might well be what we have been experiencing these past two decades in United Methodism. While I have challenged my own assumption to guard against mere wishful thinking, I have to conclude that there is plausible evidence to support the claim that we may be today, indeed, in the midst of a significant rediscovery of Wesley for our time. Consider these few items.

First, the 1988 General Conference adopted a new theological statement in which the confusing, undefined, and misleading phrase “theological pluralism” was purposefully omitted. The key phrase characterizing the new statement was “the primacy of Scripture.” It clarified for the church that Scripture does indeed take precedence over tradition, reason, and experience—helping clear up the misunderstanding of many about the oft-cited Wesleyan Quadrilateral. With this change, we are more faithful to our Wesleyan heritage.

The 1988 statement also clarified for the denomination that we do indeed have recognized “doctrinal standards”—an important action expounded helpfully by William J. Abraham in his important work Waking From Doctrinal Amnesia.

A major chunk of Good News’ energy between 1972 and 1984 was invested in critiquing and working for change in the theological statement that espoused “theological pluralism.” Good News published The Problem with Puralism: Recovering United Methodist Identity by Dr. Jerry L. Walls.

More than 13,000 petitions were sent to the 1984 General Conference, many generated by Good News. A significant number sought to amend the Discipline’s problematic theological statement. The surprising result was that delegates named a new theological task force to prepare a new theological statement for the church, which was approved at the 1988 Conference.

At the 1988 General Conference, delegates approved a new hymnal for the church, which included scores of Charles Wesley’s hymns not found in the 1964 hymnal. For two decades now, this treasure trove of Wesley’s hymns have enriched our worship and helped deepen our understanding of our Wesleyan theological heritage.

Second, one can’t help but be impressed with the resurgence of books focused on all aspects of Wesley’s theology. Credit needs to be given where due. A Foundation for Theological Education (AFTE), launched back in 1976 by Ed Robb, Albert Outler, and others, has had a major impact on the current renewal of interest in Wesley studies, with more than 120 scholars having become John Wesley Fellows.

One thinks of Kenneth Collins’ The Theology of John Wesley and The Scripture Way of Salvation, Bishop Scott Jones’ United Methodist Doctrine and John Wesley’s Conception and Use of Scripture, Thomas C. Oden’s John Wesley’s Scriptural Christianity and his invaluable Doctrinal Standards in the Wesleyan Tradition, a 2008 revision of his 1988 work by the same title. One might add Randy Maddox’s Responsible Grace: John Wesley’s Practical Theology and Henry H. (Hal) Knight’s The Presence of God in the Christian Life: John Wesley and the Means of Grace. Additional works by Steve Harper, Geoffrey Wainright, Robert Tuttle, Ted Campbell, Richard Heitzenrater, and others would be a part of this rediscovery of Wesley.

Several years ago, Bristol published The Albert Outler Library, an impressive nine-volume work of the papers and works of the late Albert C. Outler, one of United Methodism’s most eminent Wesleyan scholars. The series includes Albert C. Outler: The Gifted Dilettante, a delightful biography by Bob Parrott, who also served as general editor of the Outler Library project.

In reflecting on this resurgence, I would also include the important three-volume work by my friend Kenneth Kinghorn, long time professor at Asbury Theological Seminary, on The Standard Sermons in Modern English (Abingdon Press). The goal of the work was to render John Wesley’s eighteenth-century language into a form more suitable and understandable for today’s reader, but with no dumbing down. Ken told me recently that his more contemporary translation is helping Wesley’s sermons get translated into Japanese, Swedish, and Russian and most certainly will be helpful as the complete works of Wesley are currently being translated into Korean.

Two other works I must mention. The first is Riley Case’s Evangelical & Methodist: A Popular History (Abingdon, 2004). This superb volume is by a former district superintendent in the North Indiana Conference who has been a long-time Good News board member and part-time writer for The Confessing Movement. He documents evangelical renewal within Methodism as the church evolved into two strands—one of established respectability in a more liberal theological tradition and the other strand being more populist, orthodox, and evangelical.

The other work is Faye Short and Kathryn Kiser’s Reclaiming the Wesleyan Social Witness: Offering Christ (Providence House Publishers, 2008). As a project of Good News’ Renew Network, this volume gave the church an important work with a balanced focus on vital personal faith and the resulting necessary expression that Wesley called “faith working by love.”

Third and last, it is highly significant that the 2008 General Conference launched a major quadrennial thrust for the denomination urging us all—churches and program boards and agencies—to focus on “Living the Wesleyan Way.” Our bishops are challenging us to give serious thought again about what it means to believe and live as Wesley did when God used him and his brother so mightily. The United Methodist Publishing House has done its part in giving the church The Wesley Study Bible, a modestly-priced and impressive resource worth getting and using until you wear it out.

Well, what shall we say to all this? Might the United Methodist Church be in the process of rediscovering Wesley? It just could be that we are. Many have been praying earnestly for years for that to happen. Perhaps we are seeing answers to those prayers. There is certainly an openness to our Wesleyan/EUB evangelical heritage that we have not seen in more than a generation.

In the last chapter of Basic United Methodist Beliefs, Robert E. Coleman writes on “How Revival Comes.” Coleman is an author, evangelism professor, and former director of the Billy Graham Institute in Wheaton who has translations of his books published in 82 languages. He reminds us that “Methodism at heart is a revival movement. When the Spirit of revival does not pervade the church, the body may survive as an institution but it is lifeless.” The basic concept behind revival, says Coleman, is “the return of something to its true nature and purpose.”

Wesley’s question to his followers remains timely for us today: “What can be done in order to revive the work of God where it is decayed?” It may well be that rediscovering Wesley will help us better understand just what the “work of God” is that we should be about, and remind us as well that it must be done with a continued fresh anointing of the Holy Spirit.

Friends, Wesleyan revitalization and doctrinal renewal are concerns that have been right at the heart of Good News’ ministry from the very beginning. As I watch the strong and able new leadership, I know the ministry remains true.

In numerous ways, Good News continues to make a very significant contribution to renewal in the United Methodist Church. In these days of profound moral and spiritual challenge, I remain grateful for your faithful support of Good News. Our nation and world need a vital, dynamic Wesleyan witness.

James V. Heidinger II is president and publisher emeritus of Good News. He retired in July 2009.

by Good News | Jul 23, 2010 | Magazine Articles

By George Mitrovich

Barbara Brown Taylor, a priest of the Episcopal Church and a gifted preacher and writer, sent me an email saying she had gone on a walk one afternoon near her Georgia home when I came to mind. She said she wondered, “How’s my Arminian friend?” I was pleased to receive her note. It’s nice to be thought of, especially by someone I admire as greatly as Barbara.

A few years back she was in San Diego to speak to a national convention of Puritans, more than 2,000 of them (no, really, Puritans). I had the privilege of having lunch with Barbara and during our time together I brought up James Arminius, the Dutch theologian and ultimate contra- Calvinist. I have a habit of doing that, of asking others if they know Arminius.

For 400 years Arminius has been overlooked in Western history. Am I alone in thinking that? No, but the number of those who share that view, weighed against Martin Luther and John Calvin, is small. But, in this context, numbers do not impress me. I am confident of the debt owed by the West to Arminius, who dared to declare, despite the fierceness of his Calvinist foes, that God loves every man, not an elect few. That belief would shake the foundations of both church and state in the Netherlands and, in time, would impact the life of John Wesley, who in turn as a priest in the Church of England would begin a spiritual and social revolution resulting in sweeping changes in English society. As Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli said, “The Wesleyan Revival saved England from the blood bath that engulfed the French.”

John Wesley’s remarkable leadership would also bring about the Methodist Church in America, whose origins in 1784 at Lovely Lane Chapel in Baltimore, would give rise to the nation’s most important Protestant denomination—and in all of this the influence of James Arminius cannot be overstated (although understated it remains).

There are 11 million websites about John Calvin on Google, 98,000 for Arminius. When the 400th anniversary of Arminius’ birth took place (1559) it was barely noted, but during the 500th anniversary of Calvin’s birth (July 10, 1509), he was remembered worldwide. In America, for good or ill, you cannot escape Calvin—and his influence has been hugely consequential.

As the historian Richard Hooker put it: “Perhaps even more so than Martin Luther, Calvin created the patterns and thought that would dominate Western culture throughout the modern period. American culture, in particular, is thoroughly Calvinist in some form or another; at the heart of the way Americans think and act, you’ll find this fierce and imposing reformer.”

Magisterial study

All of which I note to report I finally read Dr. Carl Bangs’ magisterial study, Arminius: A Study in the Dutch Reformation (Abingdon, 1971), an engrossing read of 380 pages (bibliography and index included). It’s embarrassing to think how long the book sat on my shelf. Occasionally I would take it down and read chapters here or there, but never the whole of it, until now. True, I’ve read many articles about Arminius, but never the definitive study of his life—as Dr. Bangs’ book assuredly is.

It is not an easy read, but how could it be? The time Dr. Bangs was writing about differs dramatically from ours, as much as horse-drawn carriages differ from Stealth bombers. (If you read it, forget about trying to pronounce Dutch names, it will only slow you down. Unless, of course, Cornelis Cornelisz Heemskerck, rolls easily off your tongue.)

During Arminius’ life, the people of the Netherlands were focused on the war against Spain and the establishment of trade with the East Indies, but a theological conflict between the followers of Calvin and those of Arminius also drew their attention, for it threatened the nation’s stability. The States General repeatedly sought to broker peace between the disputants, but to no avail. It beggars the mind of modernity that a nation’s well-being might depend upon resolving theological differences, that such matters were referred to the civil authorities and not the church, but it did—and by such a clash the distinction between past and present is measured. (In this I may err, since theology drives the abortion/gay marriage debate, but for me it doesn’t rise to the same level.)

Dr. Bangs introduced me to a Latin phrase, Libertas Voluntatia, which means the liberty of the will. It is a phrase that shall mark my days, as it marked Arminius’.

Being Arminian

From the time I became a Christian in my mid-teens under the preaching and influence of Nicholas A. Hull at University Avenue Church of the Nazarene in San Diego, Arminius has loomed large in my life. Reverend Hull, an FDR Democrat from Arkansas, would say to the men in his congregation that to be a “Christian you should vote Democrat and carry a pocketknife.” (I think he was teasing about the pocketknife.) The Nazarenes, unlike most Methodists of my experience, were seriously Arminian/Wesleyan in their theology, and members were expected to know what it meant to be an “Arminian.” (That judgment is a reflection on the fact that I am a United Methodist in the Western Jurisdiction of our church, one overwhelmingly liberal in theology.)

Whether that emphasis among Nazarenes remains true I can’t say, because I’ve been a Methodist for 48 years, but in terms of the theological influences in my life the Nazarenes, by virtue of their fidelity to Arminius, win out.

The great theological divide between denominations today is not over free will and predestination, but between liberal and conservative theology. People join churches for many reasons, but despite a renewed interest in Calvinism, it is unlikely either Calvin of Geneva or Arminius of Leiden factor in their decision. The church world some of us knew growing up is largely over (thanks be to God).

To cite but one example of how Protestantism is different today, I referenced Mt. Pleasant Christian Church in Indianapolis, Indiana, a large independent evangelical church. I’ve read their “What we believe” statement. It consists of seven faith affirmations consisting of 174 words, including Scripture references. By contrast the writings of Arminius alone fill three volumes, and it was not uncommon for him to write 200-page letters in Latin to affirm a theological point. Which is why Bruce Gordon, professor of Reformation history at Yale Divinity School, tells us in his new biography of Calvin, that to understand a time 500 or 400 years distant calls for the suspension of “modern sensibilities.” No doubt.

Studying Calvin

I gave a talk recently on John Calvin to the Koinonia adult Bible class at San Diego’s First United Methodist Church, where I am a member. I did my due diligence, as I wanted to be fair to Calvin.

I read part of Dr. Gordon’s biography, which has been critically acclaimed. I read critiques of the Institutes of the Christian Religion, Calvin’s magnum opus. I read The Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England (adopted in 1563), which in Article 17 endorses predestination (reflecting Calvin’s curious hold on the Anglicans). I read again about the Synod of Dort, which occurred in 1618-19, and whose delegates, from church and state, ruled for Calvin and against Arminius, resulting in a pogrom against Arminius’ followers, including clergy and citizens who were banned by the States General—from both church and civil employment. But it didn’t end there, as some were executed for their heresy for sharing Arminius’ belief that when Christ died on the cross he died for all.

Most notable among those tried for the crime of “heresy” was van Oldenbarnevelt, who for 33 years had faithfully served Holland as the state’s Grand Pensionary, but was beheaded at The Hague for his Arminian sympathies. Still others were hounded from the Netherlands and found refuge across the English Channel in Lincolnshire County—where on June 28, 1703,

John Wesley was born (the juxtaposition of which is critical).

If the responsibility of someone “teaching” an adult Sunday school class is to enlighten his or her hearers, to broaden their knowledge, I’m afraid in this instance I failed. I simply got too caught up in too many synods and confessions and controversies. I sought fairness in outlining Calvin’s life, but this whole history is complicated, and some have given their lives in study to unravel its complexities, as Dr. Bangs did with Arminius.

The greater man

Nothing that I read, either from John Calvin or about John Calvin, including Dr. Gordon’s mostly sympathetic biography, changed my mind on the merits of Arminius vs. Calvin. To the contrary, I came away more certain than ever that James Arminius was by far the greater man—and, because one’s humanity toward one’s fellow humans matters greatly to me, that Arminius was by far a better person than Calvin. There was about Calvin an arrogance that found its greatest manifestation in his theological certainty (you decide which preceded which, arrogance before certainty or certainty before arrogance?). His habits of life demanded of others conformity of thought and contrasted dramatically with Arminius’ gentleness of spirit and acceptance of others.

I concede in advance that it may be unfair to say that Calvin’s only display of humanity and tolerance was allowing his congregants in Geneva to sing during night services (Calvin believed music had no place in the church). But, in a spirit of Christian charity, I should allow that his arrogance and certainties were God’s doing and therefore we should hold God accountable for Calvin being Calvin not Calvin for being Calvin. Why? By Calvin’s own reasoning God predestined all things and thus Calvin was in consequence innocent of his actions and helpless to do otherwise (so he gets a pass on his role in the burning of Michael Servetus at the stake).

If Calvin was right, then all that’s transpired since Adam’s transgression is God’s doing. Think of all the terrible acts committed by humans against humans, from Auschwitz to Afghanistan; of all the terrible acts of nature, from Pompey to Katrina, and tell me how God gets a pass if Calvin is right? This goes to the fundamentals of Calvin’s theology, which places God as first cause and thereby the causation of all things—both good and ill.

Arminius believed Calvin was wrong and that God’s love is all encompassing. You may deconstruct John 3:16 any way you choose, but in the end it either affirms what it says or it doesn’t; either Jesus died on the cross for all or he didn’t; either he came to save the world or Calvary was a hoax. Even Jacques Derrida, the late great French deconstructionist, could not have interpreted John 3:16 otherwise. (It should be noted, however, that one of the major disputes between Arminius and the Calvinists, was over Romans 7, not John 3:16.)

Sovereignty of God

Am I saying then that those who embrace Calvin, who hold tightly to his doctrine of predestination, who count themselves eternally saved and others eternally dammed, have believed a lie? No. They believe and believe sincerely, as did Calvin, but they like him believe in error. I do not judge them harshly for their beliefs. Their state of grace is wholly God’s and they are by Arminius’ reckoning no less worthy of God’s love in Christ than we. The contrary edicts of Calvin are not true, but ultimately they are inconsequential because our one shared certainty, whether Arminian or Calvinist, is the sovereignty of God, and by his decree all else is secondary, including the most overly wrought and expansive of theological disputations—and such disputations were dominant in the world of ideas for 1,000 years and more (there was a reason why theology is known as the “Queen of the sciences”).

But to concede the last point is not to overlook what I deem, in the context of history, the damning consequences of Calvinism. It goes to the very core of why Arminius’ belief in free will (Libertas Voluntatia) and Calvin’s denial of it reverberates down the years. The former affirms liberty and God’s free grace and the latter rejects such sentiments—not in part but the whole thereof.

If those anxious as to their state of grace under Calvin’s teachings wondered if they fit in God’s plan, those in places of authority had the benefit of knowing they ruled by God’s will. How reassuring to kings and queens, to princes and magistrates, to lords and ladies of the realm, to bishops and vicars, that they had God’s favor. And if that was true, so too then was the opposite equally true. If you were numbered among the masses whose sole reason for existence was to bow your knee before your betters and serve their needs while denying your own, then that too was God’s will.

How comforting to believe that while you dined in splendor and others fought for scraps from your table, that it was all God’s doing. How liberating to know whatever the fate of others it is not your fate. How reassuring to believe God had worked it out before the foundation of the world—and you were the beneficiary of his favor.

The gifted preacher

James Arminius (the Latinized name of Jakob Harmenszoon) was born in 1569 in Oudewater, the Netherlands. In his early life, he experienced more than his share of hardship, beginning with his father’s death, when James was but an infant. His mother struggled mightily to raise and care for her children. While a student in Germany, Arminius lost his mother and siblings, who were murdered in 1575, when the Spaniards overran Oudewater, massacred its inhabitants, and destroyed the town.

Even as a child, many saw Arminius as possessing extraordinary intelligence. After completing his studies, he entered the ministry and would later become Amsterdam’s favorite and most gifted preacher. He would close out his life a highly respected and affectionately revered member of the theological faculty at Leiden, where his academic colleagues elected him Rector Magnificus in 1605.

He was highly respected and revered, that is, save for his fierce Calvinist critics, who were unrelenting in their attacks and continued to savage his reputation beyond the grave. They said he was a papist and in league with the Jesuits. They said he did not believe in the Trinity. But those were merely attacks upon his theology and church sentiments. The attacks upon his person and character were infinitely more outrageous and no less baseless in their lies. Why? For one reason and one alone—because Arminius believed contrary to Calvin.

It should be here noted that Arminius himself held a very high view of John Calvin. Of the Genevan, Arminius would write: “For I affirm that in the interpretation of Scriptures Calvin is incomparable, and that his commentaries are more to be valued than anything handed down to us in the writings of the Fathers—so much so that I concede to him a certain spirit of prophecy in which he stands distinguished above others, above most, indeed, above all.”

In this instance, as in many others, we see Arminius’ soul and character at work, the ability to rise above even the most profound theological differences and to otherwise “concede” to Calvin his due. This entry by Dr. Bangs speaks to Arminius’ deeply admirable traits of character, of his transcendent decency and caring for others.

Remembering a giant

James Arminius died on October 19, 1609 in the university town of Leiden. His funeral took place three days later in the Pieterskerk across the way from his home and near the university. At the service were his grieving admirers, friends, and family (Lijsbet Reael Arminius bore her husband many children, nine of whom survived childbirth and were living when their father passed).

Later that day in the Great Auditorium of the university, Petrus Bertius delivered the principal eulogy before faculty, students, curators, and burgomasters from The Hague, as well as friends and relatives from Amsterdam and Oudewater, who had journeyed to pay tribute to their greatest son. Of Arminius, Bertius would say near the end of his eulogy:

“There lived in Holland a man / whom they who did not know / could not sufficiently esteem / whom they who did not esteem / had never sufficiently known.”

Bertius then closed with the words from John’s Gospel, “Beloved, let us love one another.”

As I endeavor to understand my life, to account for my views, both as a person of faith and as a person who believes in a citizen’s duty to practice the ethic of civic engagement and to recognize the equality of every person, I do with gratitude allow that James Arminius, a man who lived more than 400 years ago, has immensely influenced my life and thinking—in ways beyond my accounting.

As a Christian and a Methodist, I cannot forget that absent Arminius the life and great deeds done by John Wesley would never have evolved as they did—and England and America would surely have been the lesser for it. This is an incontrovertible fact of our shared histories and the ignorance of it by secularists and non-believers in both Britain and America neither alters, changes, nor diminishes its undeniable truth.

George Mitrovich, a member of First United Methodist Church in San Diego and active in Wesleyan renewal efforts, is president of The City Club of San Diego and The Denver Forum, two leading American public forums.

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.

Lived with regrets. With such a high-profile ministry for such a lengthy duration of time, Graham was often under intense scrutiny. Was his version of Christian conversion too simplistic? Was he merely a government mouthpiece when he preached in totalitarian nations? Did he do enough with his platform for the civil rights of African Americans? Was he too comfortable in the White House? Despite the enormous audiences of curious onlookers and spiritual searchers, there were long lists of theological and social critics – both conservative and liberal – who were more than happy to offer a critique of Graham’s ministry. While some of the concerns were superficial, there were others of a more serious nature that had to be addressed.