by Steve | Jul 13, 2021 | In the News, Uncategorized

In an extremely rare move, the North Georgia Conference of the United Methodist Church has seized the assets of Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church in Marietta amid a fight over who should be its senior pastor.

In an extremely rare move, the North Georgia Conference of the United Methodist Church has seized the assets of Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church in Marietta amid a fight over who should be its senior pastor.

The conference announced its stunning decision in a statement released Monday and said it was “acting out of love for the church and its mission” and to “preserve the legacy of the Mt. Bethel church and its longstanding history of mission and ministry.”

The conference’s board of trustees will assume management of the church. Mt. Bethel, located at 4385 Lower Roswell Road in Marietta, has one of the largest congregations in the conference.

Bishop Sue Haupert-Johnson and the eight district superintendents “have unanimously determined that ‘exigent circumstances’ have threatened the continued vitality and mission of Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church,” according to the statement. “Given this determination, all assets of the local church have transferred immediately to the conference’s board of trustees of the North Georgia Conference.”

To read entire Atlanta Journal-Constitution story, click HERE.

by Steve | Apr 30, 2021 | Magazine Articles, Uncategorized

Mt. Bethel

By Rob Renfroe —

A number of our larger, most healthy churches have recently been told that their senior pastor is being moved to another appointment, without consultation with the pastor or the congregation. One is Mt. Bethel in the North Georgia Annual Conference. It’s one of the ten largest churches in the denomination. The others are in the Greater New Jersey and the California-Pacific Annual Conferences.

Thus, they are in different regions of the country. One, Mt. Bethel, is predominantly white. The other four, one in New Jersey and three in California, are Korean. What do they have in common? They are all strongly traditional in their beliefs. They are all under the authority of a centrist to progressive bishop.

Something else they have in common is that none of these churches appreciate how they have been treated in the removal of their senior pastor. All United Methodist pastors serve at the pleasure of their bishop. All United Methodists churches know their bishop has the right to appoint whoever he or she believes is best for their church. But every church and every pastor, unless there is some moral failure, expects to be treated with common courtesy and respect in the process.

Some have condemned Mt. Bethel’s unwillingness to receive a new pastor. The expected liberal critics have blasted the church for wanting to be treated differently than other churches because of its size. But these critics are missing the point. Neither the pastor nor the church’s SPRC were consulted before the appointment was announced as required in The Book of Discipline. And though larger churches are not special or above the rules because of their size, replacing their senior pastor in a way that screams, “I am the bishop and I know what’s best for you,” is not smart, respectful, or helpful to the person who is taking over the removed pastor’s position.

The senior pastor at the church I serve announced his retirement this January. The Woodlands United Methodist Church, just north of Houston, is also one of the denomination’s largest. The process of appointing his successor began three years ago. The bishop and our SPRC worked closely and amicably together with the same goals – finding the right person for the position and conducting the process in a way that guaranteed the new pastor would be well-received by the congregation and begin his or her ministry with the greatest chance of success. Replacing the pastor of a large church does not require three years. But to be effective and healthy for the church, the process – well, first it must be a process, not a pronouncement from on high – needs to be open and collaborative.

A church does not need to be the size of The Woodlands or Mt. Bethel to know when its lay leadership and its congregation are being disrespected. And it is wise to be aware that if you appoint someone to be the senior pastor of a church without proper consultation, you are likely doing harm to that congregation.

Why three different bishops would show such little regard for thriving churches and their ministries is indeed puzzling. The five churches involved have either stated or have given reason to believe they will leave the Post-Separation United Methodist Church when the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation is passed. It is easy to believe, possibly wrongly, that these disruptive appointments are punitive in nature – a way of insuring that these churches will not leave as whole and as healthy as they might have.

It’s also natural to wonder if removing beloved senior pastors is a strategic play for financial gain. If a bishop can make things so difficult for a traditional church that it decides to leave before the Protocol is passed, it will need to pay a high financial price for disaffiliation. In the case of Mt. Bethel it could be several millions of dollars. It makes sense. If a church leaves after the Protocol, it takes its property and its assets without any payment to the Post-Separation UM Church.

So, what does a bishop have to lose if she or he so offends a traditional congregation that it decides to leave early? It was departing anyway. Why not fill dwindling annual conference coffers with a costly disaffiliation exit fee? In fact, it might be considered a shrewd play. Turn up the heat until the church feels it must depart – either leaving its buildings and property behind or paying dearly for the privilege of taking what it has sacrificed to build over the decades.

Another possibility is that a bishop, by disrespecting a congregation, could hope to run off all of its strongly traditional members. Make them so upset that they decide to leave and form a new church. Those remaining would have decided they could live with such a bishop and the UM denomination he or she represents. They would also retain the rights to the property. Perhaps those who stay would vote to remain in the post-separation UM Church, the denomination that bishop represents, and bring their buildings and their assets with them.

It’s hard to believe that any representative of Christ, particularly bishops of The United Methodist Church, would be cynical and Machiavellian enough to play these games. Especially one who told the Washington Post after the 2019 General Conference, “If the Methodist church has to get leaner and nicer, I’m all for it. I’m tired of the meanness. I’m tired of the pettiness. I’m tired of the fighting to win at all costs.”

And one would think that, in this time when we have all become aware of how Asian Americans are often the victims of prejudice and mistreatment, bishops would be sensitive to the optics of how they treat predominantly Asian congregations and clergy.

But three different Annual Conferences. Three different centrist to progressive bishops. Five different traditional churches. One has to wonder what’s behind it. And where it will go next.

Rob Renfroe is a United Methodist clergyperson and the president and publisher of Good News.

by Steve | Jul 1, 2019 | Uncategorized

By Kenneth Tanner

The hands that crafted humanity from the dust are the hands that grasp Mary’s finger as she looks on her infant God with awe.

The divine finger that etched the commandment concerning adultery into the stone on Sinai is the human finger that drew in the sand as the frenzied crowd picked up stones to slay the adulteress.

The hand that wrote on the palace wall that Belshazzar, the pagan king, had been weighed in the balance and found wanting is the hand that was nailed to the tree and bled for the failures and imbalances of every human tribe.

The fingers that set the moons and stars in the cosmos like a master jeweler, smear mud on the eyes of the blind so that they might once again behold the light of heaven.

And even as the cosmos is held in his hands – suspended on his charity, all things set in motion by his energies – his sacred hands are contained and constrained for nine months within the womb of the virgin.

The hands that deliver Israel from slavery in Egypt are the hands that offer the paschal cup that promises and will in time deliver the renewal of all things.

He opens his sovereign hands and feeds all the woodland, pasture, and desert creatures and his calloused carpenter’s hands take, and bless, and break the bread that grants life without end, the bread of Christ.

As the right hand of the Father Jesus touches lepers, dines with tax collectors, offers living water to the woman whose people are the enemy of his people, and washes the feet of his followers – cleansing everyone he meets, because the Son only ever does what he sees his Father doing – and is the risen, transfigured right hand that rests on the shoulder of John in the apostle’s great vision of the world that is coming to this world, and says to his beloved friend in a still small voice: “Don’t be afraid! I am the First and the Last. I am the living one. I died, but look – I am alive forever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and the grave.”

Kenneth Tanner is pastor of Church of the Holy Redeemer in Rochester Hills, Michigan. His writing has appeared in Books & Culture, The Huffington Post, Sojourners, National Review, and Christianity Today. This article appeared in the July/August 2019 issue of Good News. Artwork is a segment of Michelangelo’s “Hand of God: The Creation of Adam” found in the Sistine Chapel. Public Domain.

by Steve | May 29, 2019 | Uncategorized

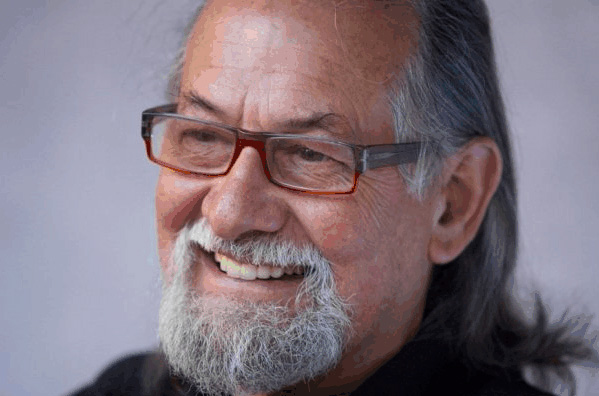

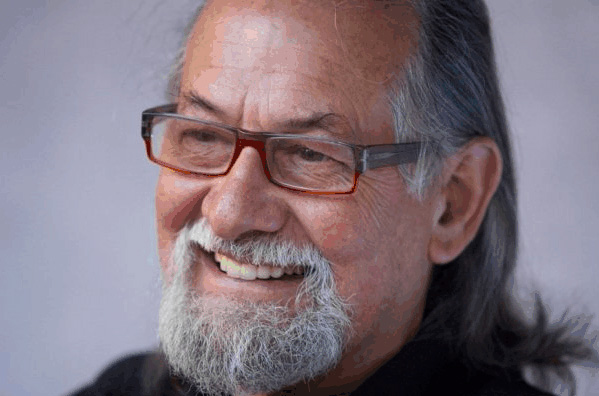

Shepherd to the fringes: John “Bullfrog” Smith (1942-2019)

By Steve Beard

March/April 2019

“Jesus was not crucified in a cathedral between two candles, but on a cross between two thieves; on the town’s garbage heap; at a crossroad so cosmopolitan that they had to write His title in Hebrew and Latin and Greek … at the kind of place where cynics talk smut, and thieves curse, and soldiers gamble. Because that is where He died. And that is what He died for. And that is what He died about. That is where churchmen ought to be and what churchmen ought to be about.”– The Rev. George Macleod, Church of Scotland clergyman and one of the founders of the Iona Community (1895-1991).

More than 20 years ago, I was sitting across the table in a Chinese restaurant in Nicholasville, Kentucky, when John Smith recited Macleod’s sentiments with righteous authority and a piercing gaze to describe part of the inspiration of the calling on his life. At that time, Smith, a well-known media commentator and evangelist to those on the cultural fringe in Australia, was doing doctoral work in missiology at Asbury Theological Seminary.

As a well-scrubbed son of a Methodist minister and a brand new Bible school graduate in the late 1960s, Smith recalls driving past a “bunch of menacing-looking outlaw bikers parked by the side of the road. Oddly, I felt a surge of compassion for these guys who no one really wanted to know. I couldn’t see the local minister making much headway with people like that,” he wrote in his autobiography, On the Side of the Angels.

Smith began to pray that “God would raise up someone able to get alongside such outsiders and show them something of the love of Christ.” At that moment, he sensed the corresponding answer: “Why don’t you answer your own prayer.” Initially, he doubted the call – but eventually he became the president of God’s Squad Motorcycle Club and an authentic ambassador of Christ to the marginalized, rejected, and forsaken.

John Smith died on March 6, 2019, after a long battle with cancer. He was 76 years old. Hundreds of bikers were in attendance at Smith’s funeral in Ocean Grove, a coastal community in the southeast of Australia, to pay their respects – including those from the Hell’s Angels, Gypsy Jokers, Bandidos, Coffin Cheaters, and Immortals.

Sean Stillman, president of God’s Squad UK chapter and author of God’s Biker: Motorcycles and Misfits,described Smith at the funeral as an “academic, a pastor, a preacher, a prophetic voice, an irritant to a comfortable church, an advocate for justice, the poor, the marginalized, and the arts.” More significantly, Stillman said, was his role as husband to Glena, Smith’s wife, and father to his three children and 17 grandchildren.

With a gregarious personality and an encyclopedic knowledge of poetry, pop culture, ecology, philosophy, and theology, Smith garnered attention and stirred controversy through his Christian message, advocacy for social justice, and roaring motorcycles. His appeal was infectious. Currently, there are God’s Squad members in 16 nations around the globe.

Stillman reported on Smith’s ability to connect with men and women “whether it be in a smoky clubhouse bar, backstage at a rock ‘n roll gig, or in the corridors of political power, a chapel pulpit, a street corner talking to a complete stranger, sitting amid Indigenous communities, engaging in academic dialogue, or crying in the pouring rain at a graveside with a grieving family.”

Smith spoke at rock festivals, biker rallies, government hearings, secondary schools, and before the United Nations Human Rights Commission. But his real love was talking one on one with someone who felt alienated from God and the church.

“For Smithy, the road was the place of discipleship and mission, and like John Wesley, one of his mission inspirations, the world very much became his parish,” said Stillman. “It was where you worked out what it meant to be a follower of his hero, Jesus of Nazareth. The road would take you to the marginalized. He taught us that the Gospel still ought to be good news for the poor and uncomfortable news for the powerful.”

Smith was a tireless advocate for human rights and indigenous peoples. Aunty Jean Phillips, an Aboriginal Christian leader from Queensland, testified at the funeral to Smith’s friendship with the Aboriginal community and recalled his “real heart for justice.”

An email from U2 frontman Bono was even read at the funeral. “To John the Bible was an incendiary tract – not some handbook on religion,” wrote Bono. “It was not a sop for mankind’s fear of death – it was an epic poem about life. It spoke about culture, about politics, about justice.” U2 first became acquainted with Smith while touring through Australia in 1984 during the “Unforgettable Fire” tour.

Interestingly enough, the last time I saw John and his wife Glena was after a U2 concert many years ago in Chicago on Bono’s birthday during the Vertigo tour. John asked if my friend, Father Kenneth Tanner, and I could give them a lift across town after the show. They sat in the back and talked about loving the concert but being too tired to attend the after-gig birthday bash for Bono. We dutifully drove them up Lake Shore Drive to the Jesus People commune – silently wishing they had given us their passes to the after party.

Bono’s message at the funeral was spot-on: “When Bob Dylan sang ‘always on the other side of whatever side there was,’ he might have been singing about John, an outsider in an outsider community, an outlaw of a different kind preparing the way for the coming of a different kind of world, speaking truth to power.

“In our last meeting he spoke truth to me, gave me a hell of a hard time, thought I had gone soft and become too comfortable around the powerful. Thought I was living too well,” Bono recalled. “He was probably right. I still think about it.”

That was John Smith. He had the arched brow of an Old Testament prophet but the tenderness of Jesus welcoming the little children into his presence. He was pastoral and irritating. Not everyone can pull that off. It just seemed authentic with John Smith.

“For 35 years, I have been discovering that the world isn’t nearly as hostile to the gospel as I thought it would be. It is not nearly as frightening as we have been told it will be,” he wrote in the pages of Good News two decades ago. “Outside the walls of the church there are many people who want to be loved and would love to have a connection with someone that didn’t treat them like a prize to be won, but persons to be loved….

“I have spent most of my life rubbing shoulders with hippies, outlaw bikers, high school students, secular non-churched folk, artists, and just ordinary people,” Smith continued. “Sure, there are murderers and dangerous people out in the real world. But I have discovered that most people who look a bit scary are actually quite ordinary. At the same time, a lot of people who look very suave are actually very dangerous. The mafia doesn’t go around looking like hippies. They wear the best Italian suits. So if you are going to judge from appearances, you’ll fail from the start. As Jesus said, man looks on the outward appearance but God looks on the heart.”

That was the heartbeat of his message to the church.

John Smith “remained passionate about the need for the message of Jesus to be faithfully proclaimed in the public sphere, but he also taught us that it should be something that should be lived,” concluded Stillman. “Putting it into practice was not an optional extra.”

Ride on, Brother John. Thanks for the arched brow and the grin. RIP.

by Steve | May 1, 2019 | Uncategorized

By Kenneth Tanner

I find it amusing, this great befuddlement that befalls some intelligent Christians when it comes to the definition of resurrection. On Holy Saturday the New York Times published an interview with the president of Union Theological Seminary in which she mentioned Christian “obsession” with the physicality of our Lord’s resurrection.

Count me among the obsessed.

There are so many witnesses in the New Testament but John’s testimony that Jesus Christ ate with his disciples, and his words to his disciples in Luke that “a ghost does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have,” takes the guess work out of it. This is someone who remains flesh of our flesh and bone of our bone “beyond” death, the grave, and hell.

Yes, the body of Jesus Christ walks through walls and vanishes and – before resurrection – walks on water. There is great mystery here, no doubt, but we are talking about embodied mystery.

One does not have to be a skeptic or a confused cleric – this is not only about a class of over thinkers – misunderstanding of the resurrection is ubiquitous among a wide variety of believing American Christians, who have a tendency to make a ghost of Jesus, who tend to think of Jesus as disembodied in eternity, a state many American Christians consider superior to embodiment.

Americans in general have a fundamental philosophical misapprehension of human nature that assumes we are mere ghosts in machines, spirits in a material prison. Whereas Christian anthropology trusts – insists – that our created earthiness is essential to our humanity, now and for eternity; that one does not have resurrection without a body, even if that body has a transfigured physics.

As Cyril of Alexandria reminds us, echoing Paul, if Jesus does not rise again in a body of flesh – not only for a moment but forever – then death is not defeated, neither is the sin that bound in the grave and in hell everyone who shares human nature.

Jesus Christ ascends in the flesh, transformed somehow, yes, but still bearing the scars of his torment on the body Mary gave him. This is what makes the Son’s ongoing intercession for humanity so intimate and real.

As a fellow human in eternity Jesus Christ is our mediator and advocate, made like his brothers and sisters in every way so that he might be One who rules and judges those whose existence he understands from the inside, because he lived our human story with us in the most vulnerable, authentic, and beautiful way.

In Jesus Christ, God has a mother and a betrayer. In Jesus Christ, God has scars and God has memories of meals and laughter with his friends, and cold nights huddled in cloaks against the desert air; he recalls storms at sea and a grinding emptiness in his guts, dried tears on his face, at the tomb of his friend. In Jesus Christ, God knows hunger and thirst and loneliness and pain. In Jesus Christ, God knows the human devastation of disease and poverty.

And the first Christians are clear about this: the one human nature we all share has been rescued from death by the death and bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ, not only for a moment but forever. This is not a small matter where different opinions and perspectives are allowed.

You can struggle with its enormity and not comprehend it (who does), and doubting is part of being human – the “ants in the pants” of faith, as Frederick Buechner reminds us – and talking about and debating the mystery of it all is part of having faith in community with other persons, but that resurrection – Christ’s and ours – involves cells and skin and eyes and tongues and hearts and lungs (“he breathed on them”) and empty tombs – because transfigured material bodies have somehow escaped them – is a settled matter for Christians.

Yes, it is spiritual and mysterious and beyond science and nature, yes, he hides the fullness of his resurrected glory from his disciples (who could yet bear it?), and, yes, the physical resurrection of Jesus Christ is an apt metaphor now for existence and nature and our personal struggles – yes, now death is the not the end of anything or anyone, resurrection is – but resurrection as a word has that “power” because death is defeated when this one human is raised bodily and brings all our bodies with him.

Kenneth Tanner is pastor of Church of the Holy Redeemer in Rochester Hills, Michigan. His writing has appeared in Books & Culture, The Huffington Post, Sojourners, National Review, and Christianity Today. This article appeared in the May/June 2019 issue of Good News. Artwork: Jesus and the two disciples On the Road to Emmaus, by Duccio, 1308–1311, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena. Public domain.

by Steve | Mar 12, 2019 | Uncategorized

Doing General Conference Math

By Thomas Lambrecht

Supporters of the One Church Plan are considering a number of options in the wake of the decision by the 2019 General Conference to adopt the Traditional Plan. One of those options is to come back in 2020 to the General Conference in Minneapolis and attempt to reverse the result, adopting the One Church Plan in place of the Traditional Plan.

One commonly hears the statement that there were “only” 54 votes separating the two sides in 2019, which means that 28 delegates would need to change their minds and vote for the One Church Plan in order for it to pass. Those 28 delegates would most likely come from the U.S., since it is unlikely that OCP supporters will gain more adherents among the central conferences than what they already received in 2019.

But the task in 2020 for OCP supporters gets more daunting. For starters, there were 31 delegates from Africa who did not obtain a visa to attend the General Conference. If all of them are able to gain visas in 2020 (or there are replacement delegates who can), that will likely add at least 28 votes for the Traditional Plan. OCP supporters would then need to gain 42 new votes in the U.S. (half of 54 plus half of 28).

But the delegate totals will not remain the same in 2020 as they were in 2019. Due to changes in membership, Africa will gain an additional 18 delegates in 2020. That will most likely add at least 16 votes for the Traditional Plan. OCP supporters would then be up to 50 new votes required (half of 54 plus half of 28 plus half of 16).

That is not all. The U.S. delegation will lose 22 delegates. If two-thirds of U.S. delegates generally support the OCP, then the OCP would lose a net total of 8 votes. (7 votes lost would be offset by the 7 votes that the Traditional Plan would also lose in the U.S.) That means OCP supporters would then be up to 54 new votes required (half of 54 plus half of 28 plus half of 16 plus half of 8). This would be offset by potentially 5 new votes from African delegates, bringing the total new votes needed for the OCP from U.S. delegates to 49.

This means that OCP supporters would need to either convince nearly one-third of U.S. Traditional Plan supporters to change their mind, or elect OCP supporting delegates in place of TP supporting delegates. That would be a tremendous swing in votes and highly unlikely to happen.

Another way of doing the math is to look at the various constituencies and estimate what percentage of them would vote for the Traditional Plan. The totals could look something like this:

33 percent of U.S. delegates (482) equals 159.

80 percent of Filipino delegates (52) equals 42.

90 percent of African delegates (278) equals 250.

50 percent of European and Eurasian delegates (40) equals 20.

The Total for the Traditional Plan would then be 471, which would leave 391 delegates supporting the OCP, a difference of 80 votes.

Based on this second method, OCP supporters would need to “flip” 41 delegates in order to gain a bare majority. This represents one-fourth of U.S. Traditional Plan supporters who would have to change their vote. Again, this would be a very significant shift.

There are of course some variables in all these math “problems.” But the bottom line is that a lot of circumstances would have to break one way in order for the OCP to gain the votes needed to reverse the results of the 2019 General Conference.

Of course, the OCP supporters could still try to delay and obstruct the will of the General Conference, as they did in St. Louis. But why? As Africa continues to grow in membership and the U.S. continues to decline, the numbers will only get more daunting for OCP supporters.

And the prospect of another public legislative battle, with all the vitriolic rhetoric that came from the progressive side, would only continue to damage the church. I have read numerous remarks by people on social media saying their relationships with persons on the “other side of the aisle” had been damaged by the process at St. Louis. At least one newspaper described what is happening in The United Methodist Church as a “civil war.” Is that what we want to perpetuate?

Based on the public responses from many on the moderate to progressive side, they cannot continue to serve in a church that does not allow them to perform same-sex weddings and ordain self-avowed practicing homosexuals as clergy. They desired unity in the church, as long as it meant that they could engage in ministry the way they wanted to do so. But faced with a choice between unity and denying their principles, they are choosing to adhere to their principles, even if it means disunity.

So would it not be more productive for persons across the theological spectrum to agree on a way to separate from each other, freeing everyone to engage in ministry the way they believe God is leading them? An equitable way could be found to divide assets and provide for the continuation of vital ministries such as UMCOR, Wespath, GBGM, Communications, and Archives and History.

Freed from the need to continue fighting one another, the resulting new denominations could devote their whole energies to evangelism, church planting, discipleship, missions, and social action – all according to each group’s theological perspective. In areas where there is agreement, the new groups could continue to cooperate on joint projects and mission endeavors.

In the end, The United Methodist Church does not face a math problem, but a spiritual problem. Is it now possible to choose a different path, one that leads to a constructive future, rather than a destructive one for the church? Can we not work toward a different form of unity that allows for both the separation needed and the possibility of cooperation where warranted? The former United Methodist Church is already dead. We are in the birth process of something new. Can we work together to create that new reality in as painless and Christ-like a way as possible?

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. He is a member of the Commission on a Way Forward.

In an extremely rare move, the North Georgia Conference of the United Methodist Church has seized the assets of Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church in Marietta amid a fight over who should be its senior pastor.

In an extremely rare move, the North Georgia Conference of the United Methodist Church has seized the assets of Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church in Marietta amid a fight over who should be its senior pastor.