by Good News | Sep 1, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

This community well in the Republic of the Congo is one of the more than 100 wells that the Woodworth Foundation has drilled in Africa to provide safe water for residents. Photo by the Rev. Kyungu Bertie, courtesy of the Oklahoma United Methodist Foundation.

By Boyce A. Bowdon –

It was Wednesday, May 27, 1981. The session of the Oklahoma Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church was underway at Boston Avenue Church in Tulsa. Next on the agenda was a presentation of the largest gift for missions the Oklahoma Conference had ever received: a multi-million-dollar-bequest from the estates of Wynne Wayland “W.W.” Woodworth and Rose Woodworth, a Methodist couple from southcentral Oklahoma who died during the 1950s.

Winston Acree – the Woodworths’ long-time friend and business associate who had administered their estates – began his presentation by telling why they settled in Oklahoma (still Indian Territory) back in 1903. W.W. was 24 and Rose was 27. Married less than a year, the couple had been living in Jennings, Louisiana, a town near Lake Charles. They had been getting by on what W.W. earned as a barber, but they wanted to do more than get by. One of W.W.’s brothers, Lyle, had settled in Edenvale, California. In his letters to W.W. and Rose, Lyle had assured them if they moved to Edenvale they would prosper. They decided to follow his suggestion.

California was about 2,000 miles from Jennings. Acree explained that most Americans with that far to go went on stagecoaches or trains; they didn’t drive their cars because they believed cars were a passing fancy. Not the Woodworths. They decided to drive. After several days, they travelled across Louisiana and Texas and into the Chickasaw Nation of Indian Territory. They had noticed steam spewing from the radiator. It had happened before. Just as they were coming into a town called Cornish, Oklahoma, the motor died and the car coasted to a stop.

W.W. waited until the radiator cooled, then filled it with water. Then he tried to start the car, but it wouldn’t start. After several failed attempts, he realized that the engine was damaged beyond repair. They were stranded. Acree said the Woodworths gave up their dreams of California and settled down in Cornish.

Acree told the session of the instructions Rose and W.W. designated in their wills for the distribution of their estates. Rose died of cancer in August 1951 at age 74, and W.W. died in December 1958 at age 79. They did not have children of their own. Both of them left three-fourths of their estates to what soon became the Oklahoma Conference of the United Methodist Church to be used only for mission causes.

The Oklahoma Conference share of Rose’s estate was $312,506 and the portion from W.W.’s was $1,300,000, totaling more than $1.6 million. Hoping to increase the value of their estates, they arranged with Acree to manage their estates for 21 years after the death of the one of them who died last, and to add the earnings to their estates. They also instructed Acree to distribute a percentage of the earnings periodically to ministries so they would have money for mission work.

Acree said during the 21 years that he administered the two estates, he distributed $10 million to various ministries. The money provided scholarships that helped educate doctors, nurses, teachers, missionaries, and other caregivers in mission ministries; relief funds for places devastated by natural disasters; grants to help start ministries for emerging mission projects, and funds for various other mission work all over the world. While Acree spoke, people paraded through the sanctuary carrying banners with the names of ministries that were recipients from the Woodworth funds.

Acree then a handed a check to Howard Plowman, chair of the Oklahoma Conference Board of Global Ministries, for the balance in the two Woodworth Estates. The check was for $4,123,000. Added to the $10 million Acree had already distributed, that meant the Woodworth estates as of May 27, 1981, had provided more than $14 million for missions. Since 1981, Woodworth Estate has provided an additional $20 million.

Acree closed his presentation with a personal statement: “My father died when I was 13, and from then on the Woodworths were like parents to me … When they asked me to administer their estates, I was determined to do everything within my power to be faithful to the trust they placed in me.” He paused. “I am grateful God enabled me to do what I had been entrusted to do. Today is the happiest day of my life!”

As director of communications for the conference, I wanted to know more about the Woodworths. I called Winston Acree, the man who knew them best and loved them most. He said he would be at the conference headquarters in Oklahoma City the next Wednesday and would be glad to drop by my office.

When asked about their attempted cross-country journey, he wasn’t surprised the Woodworths decided to drive their car instead of taking a stagecoach or train like most people did. “They didn’t always do what most people did,” he explained. “Mr. Woodworth and Rose could see potential most people didn’t see. I think they saw cars had tremendous potential and they sensed the day was coming when most people would drive cars to get across town or across the country.”

Asked about how the Woodworths reacted when their car left them stranded, Acree (pictured right) said he had been with them during or immediately following two bank robberies, numerous booms and busts in the oil business, and the devastating Oklahoma Dust Bowl and the Great Depression that depleted Oklahoma’s population. “I never saw them panic,” Acree said. “They were always looking for the best way to fix a problem, not for somebody to blame it on.”

In response to my question about how the Woodworths prospered in a place with limited opportunity, Acree said their industriousness was a big factor. Referring back to when the car left them stranded, he said as soon as they decided to settle where they were, W.W. started looking for a job, found one at the sawmill, and took it.

W. W. Woodworth (pictured here) and his wife Rose settled in Oklahoma after their car broke down. They prospered and left

millions to Methodist missions. Photo courtesy of David Acree.

“The owner of the sawmill was impressed by how diligently W.W. worked and how well he got along with everybody. In a couple years, he offered to sell the sawmill to the Woodworths. Using money they had saved to get started in California, and some they had saved from sawmill earnings, the Woodworths bought the business.” In 1907, soon after Oklahoma become a state, construction began on the Cornish Orphans Home, which was to house 1,500 children. Stimulated by the construction, Cornish grew and so did the Woodworths’ lumber business.

In 1912, a railroad came into the area, bypassing Cornish by a mile. The Woodworths and most residents of Cornish moved to be near it and starting a new town: Ringling. The Woodworths kept the sawmill in Cornish and started a new one in Ringling. A few years later, they sold both sawmills, and used what they got for them to buy the controlling interest in the bank at Ringling. W.W. soon became bank president.

In 1913, a major oil boom began in Healdton, about 25 miles from Ringling. The Woodworths owned land in the area, drilled on it and struck oil. They used the money from the oil to buy more land, drilled on it, struck more oil, and made more money.

Winston Acree

“I’ll never forget what Mr. Woodworth told me made the biggest difference in their lives,” Acree said. “He said what helped them most was a lesson he learned from his father. It was John Wesley’s formula for making money a blessing instead of a curse: ‘Gain all you can, save all you can, and give all you can.’” W.W.’s father made a living for his family by farming and was also a local preacher in the Methodist Church and had studied the teachings of John Wesley while preparing for the ministry.

While he was still in his teens, W.W. committed himself to follow Wesley’s formula, and years later, when he told Rose about it, she made the same commitment. “Mr. Woodworth told me that he and Rose tried their best to gain all they could, save all they could, and give all they could,” Acree said. “He believed their commitment influenced everything they did that helped them prosper – not just financially, but in all ways.”

Why did the Woodworths give most of their estate to Oklahoma Methodists to use for missions? Acree said Rose answered this question in her Last Will and Testament, which she signed in November 1950. “Rose had been fighting cancer a couple of years,” he said. “Her doctors had done everything medical science of the day could do. She knew she didn’t have long to live.”

The Woodworth Estate recently gave the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference a $1 million grant. Bishop Jimmy Nunn ordains Eli McHenry during a recent recent service for the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference. Photo by the Rev. David Wilson.

Rose spelled out in her own words the two reasons she was giving most of her estate for missions. First, she believed “the very preservation of civilization itself depended upon the acceptance of Christianity by people throughout the world.” Second, she wanted “to make some contribution to enable this to happen.” When Rose told W.W. what she had decided to do with her estate, he immediately replied that he would do same with his.

Acree was not surprised when Rose and W.W. decided to give most of their wealth to Oklahoma Conference for mission ministries. “As long as I had known them, they had used their money to help support worthy causes, and obviously they thought there was no more worthy cause. I believed the greatest satisfaction they ever received from their money came from sharing it.”

Sharing what God entrusted into their care was a way for W.W. and Rose to be faithful to what Jesus called the greatest of all God’s commandments. It was what motivated, sustained, and empowered them. Sharing was a way to love the Lord – to express their gratitude for God’s blessings, to demonstrate their trust in God, and to continue carrying out their commitment to let God work through them. It was a way to express their love for their neighbors: to show compassion, to ease pain, to open opportunities, and to stimulate hope. Above all: to help others experience God’s empowering love. Finally, sharing with what God had entrusted into their care was a way to love themselves. Nothing gave them greater satisfaction.

Boyce Bowdon, a retired United Methodist communicator and former communications director for the Oklahoma Conference, has been a frequent contributor to Good News.

An artistic rendering of Rose Woodworth.

Dr. Alan McDonald, director of dentistry, at the Neighborhood Services Organization (NSO) in Oklahoma City. The Woodworth estate has been a substantial financial supporter of the NSO. Photo by Boyce Bowdon.

by Good News | Sep 1, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

Statue of John Wesley in front of Wesley’s Chapel, City Road. Photo: Chris Lawrence (Shutterstock).

By David F. Watson –

In his influential tract “The Character of a Methodist,” John Wesley describes the kind of person he hopes God will produce through the Methodist movement. True Christianity, according to Wesley, consists not simply in belief or good works, though both proper belief and good works are important. Neither does he equate true Christianity with religious practice, though religious practices may draw us closer to God. No, he insists, there is more to our faith than believing and doing. These together give us what Wesley calls the “religion of a Pharisee.” To be clear, the religion of a Pharisee isn’t entirely a bad thing. It simply isn’t enough. Hence his essay is not called “The Beliefs of a Methodist,” “The Obligations of a Methodist,” or “The Religion of a Methodist,” but “The Character of a Methodist.”

The founder of our movement taught that true faith is not just a matter of believing or doing, but of becoming. God is making us new through the blood of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit. We are becoming what God always meant us to be.

Character Development. Today what we often call “character development” involves the cultivation of traits that will help us succeed in life. To offer one example, when I was a teenager, I went to Philmont Scout Ranch for a two-week trek through the mountains of New Mexico. Mile after mile, with a heavy pack on my back, I dragged my fourteen-year-old frame along, even when I was tired, hungry, and wanting nothing more than to watch MTV and eat potato chips. At times those hikes were rapturous experiences. I was immersed in the beauty of nature and the simplicity of life without all the “stuff” I had at home. At other times, they were difficult and tiring. They tested me and forced me to push beyond what I thought I could do at that point in my young life. Through these experiences I learned and grew. Some would say that I developed “character.” In one sense they would be exactly right. I developed traits such as perseverance, fortitude, maturity, and self-awareness.

This is not, however, what Wesley means when he refers to character. Traits like perseverance and self-awareness, for example, could be used for evil ends. Terrorists might show perseverance in pursuing catastrophic outcomes. Con artists might show self-awareness to the extent that they are cognizant of the ways in which other people perceive them. “Character development” must also take place through the sanctifying grace of God. The key is not simply the growth of one’s personal capacities, but growth in holiness.

What is holiness? It is the Spirit’s work in forming us in the likeness of Christ. It is love, as God shows us love in Scripture. It is a life that is ever more liberated from the corrupting power of sin and ever more shaped by sanctifying grace. This is more than character development. It is the development of a particularly Christian character.

It is important to emphasize that the formation of Christian character is God’s work. While we might develop traits within ourselves such as self-discipline or knowledge of some subject, we cannot make ourselves holy by our own effort. Sin is too powerful. Its gravitational pull is too strong. We cannot save ourselves from sin. Rather, we must be saved, and only God can do this.

There are practices we can engage in to invite the work of God in our lives (such as prayer, worship, fasting, and the Lord’s Supper), but apart from the work of God, none of these practices has any real power. We rely utterly on God the Father, who sent his Son Jesus Christ, and who abides with us through the Holy Spirit. Put differently, we cannot evoke Christian character from within ourselves. It comes to us by God’s sanctifying grace.

For a person to pray without ceasing means that “his heart is ever lifted up to God, and at all times and in all places.” Photo: Caleb Oquendo (Pexels).

The Love of God Shed Abroad. In response to the question, “Who is a Methodist?” then, Wesley offers this summary, which he spells out in more detail through the rest of the tract:

“A Methodist is one who has ‘the love of God shed abroad in his heart, by the Holy Ghost given unto him;’ one who ‘loves the Lord his God with all his heart, and with all his soul, and with all his mind, and with all his strength.’ God is the joy of his heart, and the desire of his soul; which is constantly crying out – ‘Whom have I in Heaven but thee, and there is none upon Earth that I desire beside thee! My God and my all! Thou art the strength of my heart and my portion for ever!’”

To have the character of a Methodist, according to Wesley, is to be changed from people who were captive to sin into people who demonstrate an overflow of love. First and foremost, we love God with a strength that can only come from God himself. God is our hope today and forever. To know and serve him is our one true and passionate desire.

God’s transforming work in our lives would be visible in a number of other ways as well. In light of the great sacrifice that Christ has made on our behalf and the salvation we have through him, we will have happiness, peace, and hope. This is not to say we will never experience other kinds of emotions, such as sadness and anger, but ultimately the joy of the Lord will prevail. We can look back on our past lives with joy when we consider the ways in which God has delivered us from sin. Likewise we can look forward with confidence to the eternal life that is our inheritance as God’s children.

In the same vein, the life of a Methodist should also be characterized by gratitude and contentment. Even though we may go through difficult circumstances, we can learn by God’s grace to give thanks in all circumstances. Wesley wrote: “He knoweth ‘both how to be abased and how to abound. Everywhere and in all things he is instructed, both to be full and to be hungry, both to abound and suffer need.’ Whether in ease or pain, whether in sickness or health, whether in life or death, he giveth thanks from the ground of the heart to him who orders it for good: knowing that as ‘every good gift cometh from above,’ so none but good can come from the Father of Lights, into whose hands he has wholly committed his body and soul, as into the hands of a faithful creator.”

Further, he instructed, a Methodist is one who prays without ceasing. This doesn’t mean we must always be in church or on our knees in prayer, nor does it mean we are always crying out to God or forming our thoughts into some conscious communication. Rather, for a person to pray without ceasing means that “his heart is ever lifted up to God, and at all times and in all places…. In retirement, or company, in leisure, business, or conversation his heart is ever with the Lord.” To pray without ceasing, then, is a way of life. It is to live with a singular focus on loving and serving God.

The change that God works in our hearts will also result in love of neighbor. We are to love every person as our own soul, whether we know that person or not. This involves not only caring for their physical needs by “feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, [and] visiting those that are sick or in prison,” but caring for their souls as well. We should aim to “awaken those that sleep in death; to bring those who are awakened to the atoning blood, that being ‘justified by faith,’ they may have ‘peace with God,’ and to provoke those who have peace with God, to abound more in love and in good works.”

Whether we approve of another person’s actions or way of living is irrelevant. We are to love all people, even our enemies, actively seeking their good. “For he ‘loves his enemies,’ yea, and the enemies of God, ‘the evil and the unthankful.’” And “if it be not in his power to do good to them that hate him, yet he ceases not to pray for them, though they continue to spurn his love, and still despitefully use him and persecute him.”

The transforming love of God will evoke certain virtues in our hearts. God will replace envy, malice, wrath, and pride with mercy, kindness, humility, meekness, and long-suffering. The fruit of the Spirit will abound. Christians will forgive those who have wronged them. They will look not to their own interests but to the interests of others. Their greatest desire will be to please God, and they will seek to live in obedience to his commandments. All their lives will be oriented toward the glory of God. For the true Christian, the unwavering rule of life is this: “Whatsoever ye do in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father by him.”

We must not allow the customs of this world to draw us away from life in God, wrote Wesley. What the world values and what God values are not the same. “[V]ice does not lose its nature, though it becomes ever so fashionable.” Gluttony, greed, and evil speaking have no place in the life of Jesus’ followers. Rather, we should focus our thoughts upon what is good and true, and we should think, speak, and act in ways that honor Christ.

To be a Methodist, for Wesley, was to be peculiar. He wrote, “By these marks, by these fruits of a living faith do we labour to distinguish ourselves from the unbelieving world, from all those whose minds or lives are not according to the gospel of Christ.” For Wesley, Methodists were not the only real Christians, but to fall into the nominal Christianity so common in his day was to cease to be either Methodist or Christian in a true sense. The Christian life is one in which God so changes our character that we cannot help but seem different to those around us. Perhaps this will once again become an expectation among the people called Methodists.

David F. Watson is a professor of New Testament and the Academic Dean at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of several books, including Scripture and the Life of God (Seedbed), and lead editor of Firebrand (firebrandmag.com).

by Good News | Aug 31, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

“Whoever welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me does not welcome me but the one who sent me” – Jesus (Mark 9:37). Photo: Shutterstock.

By Shannon Vowell –

Jesus is crazy about kids.

He talks the talk: “See that you do not despise one of these little ones, for I tell you that their angels in heaven always see the face of my Father in heaven” (Matthew 18:10).

“Whoever welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me does not welcome me but the one who sent me” (Mark 9:37).

Jesus walks the walk, too – resuscitating the dead daughters and sons of bereft parents (see Mark 5:21-43, Luke 7:11-17), pushing his disciples to see past the anti-child prejudices of their day, and demonstrating physical affection for little ones, time and time again.

Jesus’s high esteem for his personal pleasure in children motivated his most famous statement on the topic (a statement made, not coincidentally, when children were interrupting Jesus’s teaching of the adults): “But Jesus called the children to him and said, ‘Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these’” (Mark 9:37).

Based on the consistent gospel witness, being confident that Jesus is crazy about kids is a no-brainer.

If the next expression of Wesleyan Christianity is to accurately reflect Jesus’s character and priorities, we better make sure that we are crazy about kids, too – in the same way that Jesus is crazy: lavish with our love, clear in our teaching, and compassionate in our care.

That’s a tall order in 2021 – and clearly a counter-cultural calling, as well. The global Covid-19 pandemic put on stark display the troubled nature of American public schools, revealing the extent to which teaching children in this country has been superseded by other agendas. Educational disparities between economic classes are increasing. The social fabric of communities, so long woven into relationships forged in local schools, is fraying. The damage of divisiveness has been writ large in headlines but lived large in families. And that’s just in the U.S.A. – the Global Methodist Church (in formation) will need a vision for educating children in the faith that is appropriately global.

Acknowledging our starting point. Too often in recent years, as the UM Church has declined, children’s education and programming in our churches has been driven by desperation: How to attract young families? How to retain young families? How to compete with other churches who have glitzier programs and bigger budgets in the attraction/retention marketplace?

In our fog of desperation, we too often mistook entertainment-value for evangelism, and mirrored the culture around us. We pushed the “fun” aspect of time in church for children, and all but gave up on catechesis.

We unwittingly communicated to our congregations that Christian formation was an afterthought, an optional extra – that our real goal was the energetic amusement of their children. We communicated: “We are here to offer you a great option in the cafeteria of choices! Please choose us – we are just as fun as anything else you could do!”

In doing so, we set ourselves up for failure on several levels. First, casting church as a place for “fun activities” makes church one of many legitimate contenders for a family’s leisure time. “Shall we go bowling? Watch a game? Or go to church – I think there’s a bounce house this weekend?”

Second, by devaluing church to the level of entertainment, we cemented the place of club sports as “more important” than church. How to effectively argue that Johnny should be at his Confirmation Retreat instead of his baseball tournament, when the latter has been so much more consistent in messaging purpose and accountability?

And third, by making children’s programs self-contained entertainment operations – as opposed to integrating with adult education and teaching discipleship as family agenda – we have failed to engage parents in their irreplaceably vital role as disciple-makers in the home.

Kids aren’t stupid. They got the message, and became adept at holding us accountable to our own marketing schema: “It’s your job to make me want to be here. You need me more than I need you, and we both know it.”

Parents aren’t stupid, either. Since the church jumped onto the carousel of consumer choice, parents brought the same evaluative criteria to bear at church as they do everywhere else. “Am I getting my money’s worth?” and “Is my child having a good time?” replaced the far more relevant questions of “Is my child learning about God?” and “Am I participating in the process of discipling my child?”

Ultimately, what we’ve been doing for the last several decades in Methodist children’s programming qualifies as the ultimate bait and switch. We have marketed entertainment when what we are hoping to offer is relationship; we have emphasized fun when our Lord promises us joy – as the fruit of hard choices (choosing the narrow road, taking up our cross daily, dying to ourselves, etc.). No wonder United Methodism has failed its children on an EPIC scale!

How can the Global Methodist Church do better? We must move beyond talking the talk of kid-crazy Jesus love to walking the walk as Jesus did. To do so, we will need a clear purpose, a plan, and a proven pedagogy – all bathed in Holy Spirit power and undergirded with humble prayer. Further, we must prioritize the work as the urgent, central mission it is.

Why? Because the GMC’s approach to Christian education and attitude toward its youngest disciples is literally a matter of life and death for a new denomination – as we have seen, so clearly, in the old one.

Clarity of Purpose: Making Disciples. As the GMC launches, let’s first resolve to set aside the distracted, time-wasting futility of marketing church as an entertainment venue for our children. Instead, let’s articulate a clear purpose, and then evaluate ALL programming based on fulfilling that purpose. Something like this: “Christian education exists to make disciples of Jesus Christ.”

I’m not in any way advocating an anti-fun agenda, I’m simply pointing out that the fun should be a consequence of a successful mission, not the mission itself.

A few not-so-radical ideas to get us started:

• Reclaim the singular, sacred place of sabbath. A commandment to “honor God” does not have to compete with anything else. Children’s Christian education and programming begins with God-honoring.

• Invite families to grow up in Christ, together. Offer studies with components for parents and children.

• Offer mission projects that connect to these studies. Create opportunities for families to serve as families.

• Foster a church culture that assumes families pray and read scripture, as families, throughout the week. Model this, pastors and leaders. Preach and teach this.

• Keep refocusing and insisting on basic purpose: Christian education exists to form Christians. Period. Anything “extra” needs to contribute to that mission.

• Accept that there will be fewer “activities,” and much more action.

A Plan to Make Disciples. Benjamin Franklin’s famous axiom applies to Christian education as to so much else: “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” But what would a sound plan for educating the youngest disciples in a new Methodist denomination look like?

Again, we can use the failures of United Methodism’s Christian education to clarify our options and leverage insights from the debacle of public schools, too. Based on the wealth of information we have at our disposal about what does not work, it’s clear that several key components will need to feature in our planning.

1. We need a catechesis for Confirmation that applies denomination-wide. A GMC set of standards for all confirmands, toward which early years in Sunday school point, could be something as simple as questions and answers based on the Creed and the 10 Commandments. But there must be something concrete, it must contain the substance of the faith, and it must be used by all GMC churches. Why? Because in the absence of specificity, nonsense and pablum (and outright heresy) creep quietly in.

2. We need a set of age-specific goals for Christian formation that applies denomination-wide. If seven-year-olds in Mali are learning the names of the books of the Old Testament and the geography of Ancient Babylon, then seven-year-olds in Milwaukee and Malaysia are, too. This is a both/and goal: both the introduction of denominational goals for each age of child, and a commitment to forming a “common culture” of education across all the diverse regions and cultures of the new denomination. Why? Because in the absence of concrete goals, motivation fizzles. In the absence of across-the-board standards for those goals, a Tower of Babel of too many possibilities foments chaos.

3. We need parent-and-guardian complements to all catechesis, available to all adults denomination-wide. The vision for family-centered disciple-making – with the church as equipping, encouraging partner – must anchor Christian education in the GMC if we are going to be a Scripture-centered people.

4. We need curriculum that is content-rich and unequivocal about truth, curriculum that instructs. Too often, we have shied away from giving children straightforward instruction and erred on the side of therapeutic investigation: “How do you feel about this? What do you think you would have done?” etc. A child-centered lesson plan is very different from a Christ-centered lesson plan – and much less effective. We need excellent curriculum – excellently composed, excellently packaged, in service of excellence – that unabashedly invites the child learner to learn.

A Proven Pedagogy for Training Children. As the GMC builds for the future on classical Wesleyan orthodoxy, it seems appropriate that Christian education within the GMC should be based on the classical trivium by which John Wesley himself was educated. This system of education remains as effective today as several millennia ago, when Plato proposed the trivium in his Republic.

The classical trivium is a chronologically sequenced series of learning types linked to phases of human development. The earliest phase – the “grammar” years – emphasizes song, chanting, and memorization because young children love rhymes, songs, and they have a unique memory capacity. Committing scriptures to memory at an early age sets the stage for a lifetime love affair with God’s Word.

The middle phase – the “logic” years – emphasizes reasoning and logic. Tweens are famously argumentative and beginning to push against authority. This tendency can be leveraged to help build analytical skills and logical thinking (critical for apologetics).

The concluding phase – the “rhetoric” years – builds on the knowledge and skills learned in the preceding phases to help teenagers become effective communicators.

Training up children so that they not only know the truth of the gospel but can also persuasively transmit that truth to others fulfills our commitment to Christ to make disciples, even as it fulfills our commitment to our children to teach them the faith. That qualifies as a win/win proposition with eternal benefits.

Just like Jesus. There are only two episodes from Christ’s childhood extant in scripture: his presentation at the Temple as an infant, and his interaction with Temple elders as a precocious 12-year-old unwittingly left behind in Jerusalem by his parents. The Lord’s childhood as we know it is literally set in the Temple. If Jesus is our template, then we should be envisioning Church as the setting for the childhoods of Jesus-followers.

As we move toward the launch of the Global Methodist Church, I pray that we will envision our future sanctuaries, our gathering areas, and our classrooms – full of kids. And I pray that we will be totally crazy about them. Just like Jesus.

Shannon Vowell writes and teaches about making disciples of Jesus Christ. She blogs at shannonvowell.com.

by Good News | Aug 31, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church. On July 28, 2021, the Board of Trustees of the North Georgia Conference and Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church issued the following joint statement: Mt. Bethel UM Church and the North Georgia Conference of The United Methodist Church have jointly agreed to use their best efforts to resolve an ongoing dispute through a mediation process and will refrain from public comment on this matter until the mediation process has concluded. Mt. Bethel Christian Academy will also be included in the mediation process. Photo courtesy of Mt. Bethel.

By Thomas Lambrecht –

This is a time fraught with anxiety and frustration for many United Methodists. Some progressives are exasperated that they are unable to fully affirm LGBTQ ordination, same-sex marriage, and various gender identities.

Some traditionalists are upset at some of the ways traditionalist pastors and churches appear to have been targeted by unsympathetic bishops. Some on both sides are afraid there will not be a General Conference in 2022 or that the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation will not pass.

This has led a number of local churches to disaffiliate from the denomination. In New England and Texas, it has been primarily liberal congregations exiting. In other parts of the country, traditionalist churches have left. Someone recently counted over 100 congregations that had departed over the past year – both progressive and traditionalist.

Other churches are considering whether or not to use the recently enacted exit path (Para. 2553 adopted at the 2019 General Conference) to leave the denomination. A few have requested to do so, but have been turned down by their bishop or their annual conference. We frequently get calls or emails from pastors or lay leaders asking what is involved in leaving the denomination. Tragically, in a few annual conferences, even asking that question can lead to the annual conference closing the church and dismissing the pastor.

The Cost of Departure. A major obstacle to churches wanting to depart from the denomination is cost. The minimum costs involve payment of two years’ apportionments plus the local church’s pension withdrawal liability.

Let’s take a concrete example of a fairly typical 170-member congregation. Its annual budget is around $290,000, including annual apportionments of $33,000. We have been told that a local church’s pension withdrawal liability can range from 4 – 8 times their annual apportionment. (That figure changes from year to year depending on the performance of the stock market.) That means the pension figure could run from $132,000 to $264,000. Add to that two years’ apportionments of $66,000. That means the cost for this church to leave the denomination now could be anywhere from $198,000 to $330,000. This church could spend from 68 to 115 percent of one year’s budget to leave the denomination now.

Some annual conferences are adding payments to what the General Conference enacted. One conference is requiring churches to pay 30 percent of the assessed value of the property on top of the above listed payments. (This is being challenged before the Judicial Council.) In the example of the congregation above, their property is valued at $8 million. That means an extra $2.4 million, bringing the total to $2.6 to $2.7 million in order to depart.

The numbers for a smaller, 70-member congregation are similar. Their annual budget is $52,800, with apportionments of $7,180. The departure cost for apportionments and pension liabilities could total between $43,080 and $71,800. This congregation could have to pay 81 to 136 percent of its total budget to depart. The property value of $1.5 million could add another 450,000 to that figure. (Please note that apportionment and budget numbers vary in different annual conferences and different congregations. Readers are encouraged to run the numbers for their own local church to get an idea of cost.)

All payments to the annual conference would have to be made prior to the local church’s departure. For most churches, this payout would be impossible. At best, it would strain the church’s financial resources and subtract from money being available for ongoing mission and ministry. Even if the church had no apportionment payments following departure, it would take 6-10 years to break even.

Of course, the compensation for paying all this liability now is that it would release the congregation from any future pension liability. Even if it joins the proposed Global Methodist Church or another Methodist body, it would carry with it no future liability. At the same time, it is uncertain whether any or all of that future liability would ever have to be paid. As long as the stock market does reasonably well, the church (or the new denomination) may never have to pay it.

Under the Protocol, this same congregation would owe zero dollars in order to separate and align with the new Global Methodist Church. They would not have to pay back any loans or grants given them by the annual conference. They would not have to pay any prior unpaid apportionments. Their pension liability would be transferred to the new denomination, so would not have to be paid up front. They would not have to pay a percentage of the property value.

Just from a stewardship perspective, it does not make sense for a congregation to depart from the UM Church now, when waiting a year could save that church tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The Timing of Departure. Another obstacle to the departure of local churches is the timing and how long the process would take. Departure requires a two-thirds vote in favor by a church conference (a meeting of all church members). Para. 2553 calls for the district superintendent to convene a church conference within 120 days of when the superintendent calls for such a conference. That means, the superintendent could delay calling for a conference at the superintendent’s discretion, as long as the conference is scheduled within 120 days of the superintendent’s issuing the call. (This is one of several unfortunate loopholes in Para. 2553.)

More importantly, departure requires a majority vote in favor by the annual conference. A local church could go through all the steps to disaffiliate and then have the annual conference vote no or vote to postpone, as one congregation in Wisconsin just experienced in June.

It is unlikely that an annual conference will convene a special session just to vote on whether one or more local churches can disaffiliate. The next annual conference session would be held in May or June 2022. That is just three months before the scheduled meeting of General Conference at which the Protocol would be considered.

The timing of departure means that a church could spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to disaffiliate only three months before they could make the same decision to separate without charge. Acting to disaffiliate now at most gains a local church three months of an early exit.

By contrast, once the Protocol passes, a district superintendent would have to schedule a church conference within 60 days of the request by the local church. No discretionary delays would be allowed. Further, the annual conference would not need to vote to approve the decision to separate. So actual separation could become effective within 60-90 days (at most) following the adjournment of General Conference.

Vote Required for Separation. Another obstacle may be the two-thirds vote by the church conference required for separation now under Para. 2553. The Protocol allows the church council or equivalent body to decide whether it would take a majority vote or a two-thirds vote to separate under the Protocol. A church that might not reach the two-thirds vote for separation now could wait for the Protocol and separate under a simple majority vote of the church conference.

Reasons to Separate Now. Even given the above disadvantages, some local churches might have a legitimate reason to move into disaffiliation now. They could be in the middle of a crisis, like the Mt. Bethel Church in North Georgia, that forces them to take drastic action now. In some churches, substantial numbers of members might be threatening to leave the church unless it acts now to disaffiliate. Local leaders would have to weigh carefully the urgency of starting the disaffiliation process now, compared with the costs involved.

Another reason to disaffiliate now is if the local church wants to go independent, rather than align with the Global Methodist Church or another new Methodist expression. Churches wanting to be independent could not avail themselves of the terms of the Protocol and would have to follow Para. 2553 anyway, so there would be no point in waiting.

One reason NOT to initiate disaffiliation now is concern that General Conference will not be able to meet in 2022. Some are pessimistic that General Conference will be able to meet due to pandemic travel restrictions. While this is certainly possible, at this point it seems less likely. The Board of Global Ministries and other church leaders are working on ways to ensure that delegates are able to receive their vaccinations, which should enable them to travel to the U.S. and avoid the need for a quarantine. Members of Congress and Senate have been contacted about helping to secure visas for delegates in the event that normal visa processes are not functioning in time. U.S. citizens can now travel to Europe and at least parts of Africa without quarantine. One hopes that vaccinations will increasingly become available in Africa and the Philippines over the next six to nine months, leading to further easing in any travel restrictions.

One needs to be careful about some who are spreading false rumors about whether General Conference can be held as scheduled. One rumor is that the United Methodist General Conference is not even on the Minneapolis Convention Center website, which shows that it probably will not happen. But no events further than six months out are posted on the Convention Center website, so our meeting not being listed means absolutely nothing. Contracts have been signed and preparations for the meeting continue on schedule.

If in the spring of 2022 it becomes apparent that not all overseas delegates would be able to attend General Conference, there would still be time to set up alternatives. Many annual conferences have met virtually. The Wesleyan Covenant Association had a hybrid in-person and virtual meeting. The African Methodist Episcopal Church had a General Conference in two sites. Delegates met simultaneously in South Africa and in the U.S. There are options that would allow General Conference to meet despite some travel restrictions.

Another rumor is that the bishops will not allow the General Conference to meet or will not allow the General Conference to consider the Protocol. United Methodist bishops do not have the power to cancel General Conference. The Commission on the General Conference, of which bishops make up a small minority, makes that decision. United Methodist bishops do not set the agenda of a regular General Conference. The Agenda Committee sets the agenda and the delegates themselves approve it. All petitions legally submitted to the General Conference (including the Protocol) must be voted on at General Conference, according to the Discipline. Bishops cannot prevent General Conference from meeting, nor can they prevent the General Conference from considering the Protocol.

A further worry is, “What if the Protocol does not pass?” At this point, there is still no organized opposition to the Protocol. In fact, several annual conferences (including North Georgia, the largest U.S. conference, and California-Pacific, a very liberal conference) passed resolutions this spring favoring adoption of the Protocol. The Renewal and Reform Coalition (RRC), which includes U.S. evangelical delegates, as well as many delegates from Eastern Europe, the Philippines, and Africa, remains solidly supportive. Many progressives favor the Protocol as the best way for them to pursue their agenda of moving the church to affirm LGBT ordination and same sex marriage. In addition, many centrists are tired of the fighting and just want to resolve the conflict so the church can focus on its mission and ministry. I would not be surprised if the Protocol were to pass by a two-thirds margin at General Conference.

There are bishops who make statements like, “The Protocol will never see the light of day,” and “The Protocol will never pass.” It must be remembered that these same bishops were sure that the One Church Plan would pass the 2019 General Conference in St. Louis. (Of course, it did not.) Some bishops, like most human beings, hear what they want to hear and consider only the “evidence” that agrees with their perspective. So far, the available evidence seems to favor the passing of the Protocol, despite what some bishops think or say.

A Spiritual Perspective. In Matthew 4:1-11, we read how Jesus was tempted by the devil. The interesting thing is that all of the outcomes the devil offered to Jesus – daily provision, protection, even rule over all the kingdoms of the world – were legitimately Jesus’s to claim. God had promised all these outcomes to the Messiah, which is who Jesus was. But the devil was tempting Jesus to claim these legitimate promises in illegitimate ways before the appropriate time had come. The challenge was for Jesus to trust the will of his heavenly Father, instead of making those things happen by himself. And because Jesus had trust in a divine plan, all those promises – provision, protection, and rule – came to Jesus in a supernatural way and with perfect timing.

While there are legitimate and understandable circumstances when local churches may move toward disaffiliation now, we have to be careful we do not preempt God. We can trust God to keep his promises to us, as we remain faithful to him. And his promises to us will come to us in God’s way and in God’s time, as he leads by his Holy Spirit. Sometimes he wants us to be patient while he works things out in his way and time.

The bottom line is that, in the absence of exigent circumstances unique to a particular local church, there may be no compelling reason for local churches to leave the UM Church at this time. In fact, there are strong reasons financially and in terms of timing why waiting for the Protocol may make the best sense. And whether a church exits now through the Para. 2553 process or waits for the Protocol, there is normally no need to hire a law firm to guide the church through the process of separation.

The new Global Methodist Church, when it is formed, will benefit most from all those local churches and annual conferences that desire to align with it to act together and stay together. Working in concert, we can build a new church that is faithful to Scripture and Wesleyan doctrine, as well as effectively structured for ministry in the 21st century. What we wind up with will be worth the wait.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Good News | Aug 30, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Steve Beard –

The sun was bright and unforgiving as I paid my respects at the gravesite of Hank Williams on a bluff in Montgomery, Alabama. A cowboy hat would have helped. The heat was a far cry from the dreary night of January 1, 1953, when much of the South was covered in snow and ice at the time of the country music star’s untimely death in the back seat of his 1952 Cadillac on the way to a concert up north. He was 29 years old.

“Praise the Lord – I Saw the Light” is etched into the massive marble gravestone with rays of light descending from the heavens, splicing right through his legendary name. The column is crowned with musical notes. Below, the base of the monument is adorned by a dozen titles of his boxcar worth of hits such as “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Lovesick Blues,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and “I’ll Never Get Out of this World Alive.” Hank didn’t just tug at your heartstrings, he yanked them. Yanked hard. Dejection, cheating, and loneliness.

He also wrote loads of gospel songs. “I Saw the Light” was his most famous. No one mistook Hank for a saint, but his fans could relate to his message about one glad morning – someday in the future – when the old will be made new and there will be no more tears or toil. Situated above his first name, there is a relatively understated bronze portrait of Hank playing the guitar with his leg propped up on a bar stool. The lyrics echoed through my mind.

I wandered so aimless, life filled with sin

I wouldn’t let my dear savior in

Then Jesus came like a stranger in the night

Praise the Lord, I saw the light.

“I Saw the Light” was a hymn to remind Saturday night backsliders that Sunday morning was right around the bend. The biographies of Williams are gut-punch reading. There was a lifetime of chronic pain from spina bifida, dejection, morphine, and a distillery worth of liquor involved. There’s no need to try to paint the picture prettier than it was. Like so many of us, he was brutally conflicted between the shiny trappings of this world and the salt-of-the-earth gospel truth that he knew in his heart. Hank could have made a country hit out of St. Paul’s declaration: “I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do – this I keep on doing” (Romans 7:18-19).

In downtown Montgomery, there’s a stately statue of Hank only a stone’s throw from the storefront museum that houses his pristine Cadillac convertible. Despite its oversized and audacious curves, the backseat seemed disproportionately cramped for Hank’s lanky 6’2 frame. It was difficult to avoid mournfully staring. The museum was well-stocked with irreplaceable memorabilia, video footage, stylized stage outfits, customized cowboy boots, and photos of the heartbroken throng of all races who filled the streets when he died.

Addressing the 20,000 gathered at the Municipal Auditorium in Montgomery for Hank’s funeral, Dr. Henry L. Lyons told the mourners: “Deep down in the citadel of his inner being, there was desire, burden, fear, ambition, reverse after reverse, bitter disappointment, joy, success, and above all love for people.” He said his songs were about the “things everyone feels. Life itself.” Hank was a crooner for the every man.

Only three blocks away, Chris’ Hot Dogs was Hank’s favorite place to eat lunch. Locals told me that he wrote “Hey Good Lookin’” from one of the stools at the counter. For more than 100 years, Chris’ has been a refuge for people of all walks of life. Despite angry threats from the Ku Klux Klan, both black and white customers were served even during the segregation era. Christopher Anastasios “Mr. Chris” Katechis, a Greek immigrant, opened the diner in 1917. Over the years, he fed other notable customers such as Elvis, Oprah, a handful of U.S. Presidents, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Clark Gable.

Only three blocks away, Chris’ Hot Dogs was Hank’s favorite place to eat lunch. Locals told me that he wrote “Hey Good Lookin’” from one of the stools at the counter. For more than 100 years, Chris’ has been a refuge for people of all walks of life. Despite angry threats from the Ku Klux Klan, both black and white customers were served even during the segregation era. Christopher Anastasios “Mr. Chris” Katechis, a Greek immigrant, opened the diner in 1917. Over the years, he fed other notable customers such as Elvis, Oprah, a handful of U.S. Presidents, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Clark Gable.

It’s a bit like walking into a time warp. “We haven’t changed this place in over 70 years,” Theo, the founder’s son, told me. The stools and booths are “beginning to show their age.” After I ordered my lunch, I looked up in my booth and saw an 8×10 autographed portrait of the late Gov. George Wallace.

Chris’ Hot Dogs in Montgomery, Alabama. Photos by Steve Beard.

Vintage news footage of his infamous 1963 inauguration speech played through my mind. “Idraw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny,” Wallace declared, “and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” As I look up at his face, the image in my vision was superimposed by him defiantly standing on the steps of the University of Alabama to block two Black students from attending.

As I would come to discover, I only knew part of his story.

Long before he became nationally known as a segregationist governor, George Wallace (1919-1998) was simply a struggling lawyer who used to go to Chris’ to buy hot dogs and cigars. In an ironic twist of history, Mr. Chris also served civil rights leaders such as Rosa Parks while she waited for the bus and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. when he was the young pastor in the 1950s of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, a sanctuary in the shadow of the Alabama state capitol.

The portrait of the man peering down at me in my booth was also a perennial candidate for U.S. President. In 1972, there were a dozen Democratic candidates running in the primaries for a race that would eventually pit Richard Nixon against George McGovern. During a campaign stop in Maryland, Wallace was shot five times by an assassin. The attack would leave him permanently paralyzed.

Shortly after his brush with death, convalescing at the Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Wallace received a most unlikely visitor.

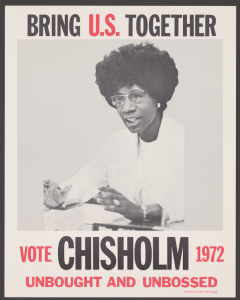

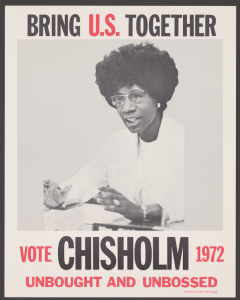

1972 campaign poster for presidential candidate and U.S. Representative Shirley Chisholm. Photo: Library of Congress.

“Shirley Chisholm! What are you doing here?” Wallace asked from his bed. Chisholm was refined, dignified, and decent. She was the first black woman elected to the U.S. Congress and in 1972 became the first African American to run for U.S. President, as well as the first woman to run for the office.

No one was more surprised than Wallace – and her staff – that she suspended her campaign and immediately went to visit her rival. “What will your people say?” Wallace asked. Chisholm responded, “I know what they are going to say. But I wouldn’t want what happened to you to happen to anyone.”

In so many ways, they represented polar opposites fifty years ago. While Wallace was the standard bearer for the Old South and segregation, Chisholm (1924-2005) was a champion of integration, women’s rights, refugees, Native Americans, and the working poor. There were few things they had in common, other than their humanity – and they were both United Methodists. They held hands and prayed together.

Wallace wept.

The medical staff asked her to end their visit because Wallace was very weak. “He held on to my hand so tightly,” Chisholm recalled, “he didn’t want me to go.”

Congresswoman Barbara Lee was a young and idealistic campaign worker for Chisholm in 1972. She was confused and upset about the Wallace visit. In a recent interview with the Washington Post she recollected how Chisholm told her, “Sometimes we have to remember we’re all human beings, and I may be able to teach him something, to help him regain his humanity, to maybe make him open his eyes to make him see something that he has not seen.”

Chisholm also said, “You always have to be optimistic that people can change, and that you can change, and that one act of kindness may make all the difference in the world.”

Chisholm understood that people were angry – very angry – but she believed “you have to rise to the occasion if you’re a leader, and you have to try to break through and you have to try and open and enlighten other people who may hate you.”

In a speech a year after the hospital visit, Chisholm, a member of Janes United Methodist Church in Brooklyn, asked, “Are we ready to learn to deal with others as God has dealt with us? God gave us life at the risk of our rebellion and paid for reconciliation at the price of the cross.”

Back in Montgomery, Wallace arrived at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on a Sunday morning in 1979 unannounced and unexpected. Without fanfare, an attendant rolled his wheelchair to the front of the sanctuary. “I’ve learned what suffering means in a way that was impossible,” he told the African American congregation. “I think I can understand something of the pain that black people have come to endure. I know I contributed to that pain and I can only ask for your forgiveness.” As he left the sanctuary, the congregation sang “Amazing Grace.”

More than twenty years before Wallace found himself before the Dexter Avenue congregation, it was the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. who said in 1957: “Forgiveness does not mean ignoring what has been done or putting a false label on an evil act. It means, rather, that the evil act no longer remains as a barrier to the relationship. … While abhorring segregation, we shall love the segregationist. This is the only way to create the beloved community.”

Shirley Chisholm did not have to approve of George Wallace’s politics in order for her to refuse to allow a barrier or a bullet to stand between them. Her faith would not allow it. A whirlwind of change took place in the man whose portrait I saw in the booth at Chris’ Hot Dogs. The news reel footage and the bitter words would never paint the whole story. Wallace was a four-term governor who sought forgiveness and ended up winning 90 percent of the African American vote during his last campaign.

The Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Steve Beard.

Upon Wallace’s death, civil rights legend John Lewis wrote a moving essay in the New York Times. “With all his failings, Mr. Wallace deserves recognition for seeking redemption for his mistakes,” he wrote, “for his willingness to change and to set things right with those he harmed and with his God.” Perhaps one of the most poignant of illustrations of Wallace’s transformed life was the attendance of Vivian Malone and James Hood, the two black students Wallace tried to bar from the University of Alabama in 1963, at his funeral.

My mind often returns to the bright sunshine on the bluff in Montgomery. A verse from “I Saw the Light” comes into clearer focus.

Just like a blind man, I wandered along

Worries and fears I claimed for my own

Then like the blind man that God gave back his sight

Praise the Lord, I saw the light.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Good News | Aug 30, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

“Jesus himself is called a light in the darkness. He is the light that darkness cannot overcome,” writes Tish Harrison Warren. (Shutterstock).

By Tish Harrison Warren –

It was a dark year in every sense. It began with the move from my sunny hometown, Austin, Texas, to Pittsburgh in early January. One week later, my dad, back in Texas, died in the middle of the night. Always towering and certain as a mountain on the horizon, he was suddenly gone.A month later, I miscarried and hemorrhaged. We made it to the hospital. I was going to be okay, but I needed surgery. They put in a line for a blood transfusion, and told me to lie still. Then, I yelled to Jonathan, lost amidst the nurses, “Compline! I want to pray Compline.” It isn’t normal – even for me – to loudly demand liturgical prayers in a crowded room in the midst of crisis. But in that moment, I needed it, as much as I needed the IV.

Relieved to have a direct command, Jonathan pulled up the Book of Common Prayer on his phone and warned the nurses, “We are both priests, and we’re going to pray now.” And then he launched in: “The Lord grant us a peaceful night and a perfect end.”

Over the metronome beat of my heart monitor, we prayed the entire nighttime prayer service. “Defend us, Lord, from the perils and dangers of this night.” We finished: “The almighty and merciful Lord, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, bless us and keep us. Amen.”

“That’s beautiful,” one of the nurses said. “I’ve never heard that before.”

Bleak season. Grief had compounded. I was homesick. The pain of losing my dad was seismic, still rattling like aftershocks. The next month we found out we were pregnant again. It felt like a miracle. In the end, however, early in my second trimester, we lost another baby, a son.

During that long year, as autumn brought darkening days and frost settled in, I was a priest who couldn’t pray.

I didn’t know how to approach God anymore. There were too many things to say, too many questions without answers. My depth of pain overshadowed my ability with words. And, more painfully, I couldn’t pray because I wasn’t sure how to trust God. Martin Luther wrote about seasons of devastation of faith, when any naïve confidence in the goodness of God withers. It’s then that we meet what Luther calls “the left hand of God.” God becomes foreign to us, perplexing, perhaps even terrifying. Adrift in the current of my own doubt and grief, I was flailing.

If you ask my husband about 2017, he says simply, ”What kept us alive was Compline.” An Anglicization of completorium, or “completion,” Compline is the last prayer office of the day in the Book of Common Prayer. It’s a prayer service designed for nighttime.

Imagine a world without electric light, a world lit dimly by torch or candle, a world full of shadows lurking with unseen terrors, a world in which no one could be summoned when a thief broke in and no ambulance could be called, a world where wild animals hid in the darkness, where demons and ghosts and other creatures of the night were living possibilities for everyone. This is the context in which the Christian practice of nighttime prayers arose, and it shapes the emotional tenor of these prayers.

Nighttime is also a pregnant symbol in the Christian tradition. God made the night. In wisdom, God made things such that every day we face a time of darkness. Yet in Revelation we’re told that at the end of all things, “night will be no more” (Revelation 22:5; cf. Isaiah 60:19). And Jesus himself is called a light in the darkness. He is the light that darkness cannot overcome.

The sixteenth-century Saint John of the Cross coined the phrase “the dark night of the soul” to refer to a time of grief, doubt, and spiritual crisis, when God seems shadowy and distant.

And in a darkness so complete that it’s hard for us to now imagine, Christians rose from their beds and prayed vigils in the night. Long after night vigils ceased to be a regular practice among families, monks continued to pray through the small hours, rising in the middle of the night to sing Psalms together, staving off the threat of darkness. Centuries of Christians have faced their fears of unknown dangers and confessed their own vulnerability each night, using the dependable words the church gave them to pray.

Of course, not all of us feel afraid at night. I have friends who relish nighttime – its stark beauty, its contemplative quiet, its space to think and pray. Yet each of us begins to feel vulnerable if the darkness is too deep or lasts too long. It is in large part due to the presence of light that we can walk around without fear at night. With the flick of a switch, we can see as well as if we were in daylight. But go out into the woods or far from civilization, and we still feel the almost primordial sense of danger and helplessness that nighttime brings.

Compline. I don’t remember when I began praying Compline. It didn’t begin dramatically. I’d heard Compline sung many times in darkened sanctuaries where I’d sneak in late and sit in silence, listening to prayers sung in perfect harmony.

In a home with two priests, copies of the Book of Common Prayer are everywhere, lying around like spare coasters. So one night, lost in the annals of forgotten nights, I picked it up and prayed Compline.

And then I kept doing it. I began praying Compline more often, barely registering it as any kind of new practice. It was just something I did, not every day, but a few nights a week, because I liked it. I found it beautiful and comforting.

For most of my life, I didn’t know there were different kinds of prayer. Prayer meant one thing only: talking to God with words I came up with. Prayer was wordy, unscripted, self-expressive, spontaneous, and original. And I still pray this way, every day. ”Free form” prayer is a good and indispensable way to pray.

But I’ve come to believe that in order to sustain faith over a lifetime, we need to learn different ways of praying. Prayer is a vast territory, with room for silence and shouting, for creativity and repetition, for original and received prayers, for imagination and reason.

I brought a friend to my Anglican church and she objected to how our liturgy contained (in her words) ”other people’s prayers.” She felt that prayer should be an original expression of one’s own thoughts, feelings, and needs. But over a lifetime the ardor of our belief will wax and wane. This is a normal part of the Christian life. Inherited prayers and practices of the church tether us to belief, far more securely than our own vacillating perspective or self-expression.

Prayer forms us. And different ways of prayer aid us just as different types of paint, canvas, color, and light aid a painter.

When I was a priest who could not pray, the prayer offices of the church were the ancient tool God used to teach me to pray again. … When we pray the prayers we’ve been given by the church – the prayers of the psalmist and the saints, the Lord’s Prayer, the Daily Office – we pray beyond what we can know, believe, or drum up in ourselves. ”Other people’s prayers” discipled me; they taught me how to believe again. The sweep of church history exclaims lex orandi, lex credendi, that the law of prayer is the law of belief. We come to God with our little belief, however fleeting and feeble, and in prayer we are taught to walk more deeply into truth.

When I was a priest who could not pray, the prayer offices of the church were the ancient tool God used to teach me to pray again. … When we pray the prayers we’ve been given by the church – the prayers of the psalmist and the saints, the Lord’s Prayer, the Daily Office – we pray beyond what we can know, believe, or drum up in ourselves. ”Other people’s prayers” discipled me; they taught me how to believe again. The sweep of church history exclaims lex orandi, lex credendi, that the law of prayer is the law of belief. We come to God with our little belief, however fleeting and feeble, and in prayer we are taught to walk more deeply into truth.

When my own dark night of the soul came in 2017, nighttime was terrifying. The stillness of night heightened my own sense of loneliness and weakness. Unlit hours brought a vacant space where there was nothing before me but my own fears and whispering doubts.

So I’d fill the long hours of darkness with glowing screens, consuming mass amounts of articles and social media, binge watching Netflix, and guzzling think pieces till I collapsed into a fitful sleep. When I tried to stop, I’d sit instead in the bare night, overwhelmed and afraid. Eventually I’d begin to cry and, feeling miserable, return to screens and distraction – because it was better than sadness. It felt easier, anyway. Less heavy.

I began seeing a counselor. When I told her about my sadness and anxiety at night, she challenged me to turn off digital devices and embrace what she called ”comfort activities” each night – a long bath, a book, a glass of wine, prayer, silence, journaling maybe.

But slowly I started to return to Compline. I needed words to contain my sadness and fear. I needed comfort, but I needed the sort of comfort that doesn’t pretend that things are shiny or safe or right in the world. I needed a comfort that looked unflinchingly at loss and death. And Compline is rung round with death.

It begins ”The Lord Almighty grant us a peaceful night and a perfect end.” A perfect end of what? I’d think – the day, the week? My life? We pray, ”Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit” – the words Jesus spoke as he was dying. We pray, ”Be our light in the darkness, O Lord, and in your great mercy defend us from all perils and dangers of this night,” because we are admitting the thing that, left on my own, I go to great lengths to avoid facing: there are perils and dangers in the night. We end Compline by praying, “That awake we may watch with Christ, and asleep we may rest in peace.” Requiescat in pace. RIP.

Compline speaks to God in the dark. And that’s what I had to learn to do – to pray in the darkness of anxiety and vulnerability, in doubt and disillusionment. It was Compline that gave words to my anxiety and grief and allowed me to reencounter the doctrines of the church not as tidy little antidotes for pain, but as a light in darkness, as good news.

There is one prayer in particular, toward the end of Compline, that came to contain my longing, pain, and hope. It’s a prayer I’ve grown to love, that has come to feel somehow like part of my own body, a prayer we’ve prayed so often now as a family that my eight-year-old can rattle it off verbatim:

“Keep watch, dear Lord, with those who work, or watch, or weep this night, and give your angels charge over those who sleep. Tend the sick, Lord Christ; give rest to the weary, bless the dying, soothe the suffering, pity the afflicted, shield the joyous; and all for your love’s sake. Amen.”

This prayer is widely attributed to St. Augustine, but he almost certainly did not write it. It seems to suddenly appear centuries after Augustine’s death. A gift, silently passed into tradition, that allowed one family at least to endure this glorious, heartbreaking mystery of faith for a little longer.

As I said this prayer each night, I saw faces. I would say ”bless the dying” and imagine the final moments of my father’s life, or my lost sons. I would pray that God would bless those who work and remember the busy nurses who had surrounded me in the hospital. I would say ”shield the joyous” and think of my daughters sleeping safely in their room, cuddled up with their stuffed owl and flamingo. I’d say ”soothe the suffering” and see my mom, newly widowed and adrift in grief on the other side of the country. I’d say ”give rest to the weary” and trace the worry lines on my husband’s sleeping face. And I would think of the collective sorrow of the world, which we all carry in big and small ways – the horrors that take away our breath, and the common, ordinary losses of all our lives.

Like a botanist listing different oak species along a trail, this prayer lists specific categories of human vulnerability. Instead of praying in general for the weak or needy, we pause before particular lived realities, unique instances of mortality and weakness, and invite God into each.

Tish Harrison Warren is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America. She is the author of Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life. This article is adapted from Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep by Tish Harrison Warren. Copyright © 2021 by Tish Harrison Warren. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA. (IVPress.com)