by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | In the News, Sept-Oct 2022

By Steve Beard

Of the more than 5,000 artifacts displayed floor-to-ceiling at The Little Museum of Dublin, few are more intriguing than a broken stained glass panel of Saint Brendan (484-577) hanging in a window. The scene portrays the beloved Irish holy man in a boat with three other monks. The poster-sized damaged window looks as though a golf ball or a mop handle knocked out a couple of sections of the illuminated glass – eliminating what once was Brendan’s face.

Thankfully, the unique piece was rescued by an architectural historian after it was thrown out of a public building in Dublin. This was not merely an overly-pious salvage operation. The stained glass panel was the treasured work of the late Harry Clarke, one of Ireland’s most spectacular visual artists. He created more than 150 stained glass windows in Catholic churches, Protestant sanctuaries, and secular venues. Clarke’s depiction of Brendan – even fractured – was a triple-barrel celebration of Irish adventurism, faith, and artistry.

Saint Brendan the Voyager (also known as the Navigator or the Bold) is one of the most celebrated ancient Irish heroes. His sea-faring nomadic spirit led him to set sail in the Atlantic to share the gospel message on distant shores 1,400 years ago. For some early Irish monks, there was a noteworthy phenomenon called peregrinatio pro Christa or “wandering for Christ.” Counterintuitively, it was a heartfelt notion that “leaving home” would free one’s soul to have a greater sense of home or intimacy with God. This is most dramatically illustrated with an incident recorded in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles in the ninth century. Three Irish monks were discovered off the coast of Cornwall, England, in a boat with no oars or rudder. “[We] stole away because we wanted for the love of God to be on pilgrimage, we cared not where,” the monks confessed.

Today, we don’t know the names of those wandering monks but Brendan’s journey lives on. Centuries after his passing, a Middle Ages blockbuster was published entitled The Voyage of Brendan (Navigatio) that chronicled his seven-year epic Atlantic journey – complete with run-ins with sea monsters and witnessing a volcano (“lumps of fiery slag from an island with rivers of gold fire”). Written by a narrator with literary embellishments and remarkable detail, the description of islands along his route have led some modern readers to believe he could possibly have reached North America hundreds of years before Columbus, Vespuci, or the Vikings.

As unlikely as that may seem to modern sensibilities, so powerful was Brendan’s tale that adventurer Tim Severin recreated a trans-Atlantic voyage in 1977 in the exact type of open vessel that carried Brendan on his oceanic quest. Severin created a 36-foot, two-masted boat with an Irish oak and ash framework wrapped with tanned and wool-greased ox hides – exactly as Brendan’s boat was described. Following the original route, Severin and his small crew sailed more than 13 months, traveled 4,500 miles, arriving on Peckford Island, Newfoundland. Severin wrote about the expedition in The Brendan Voyage. Without proving the maritime saint actually reached North America, he demonstrated that it was undeniably possible.

We will never know if Brendan the Navigator ever found the shores of North America, but we can, when faced with our own journeys and wanderings, take comfort in a simple prayer attributed to him: “Help me to journey beyond the familiar and into the unknown. Give me the faith to leave old ways and break fresh ground with you. Christ of the mysteries, I trust you to be stronger than each storm within me. I will trust in the darkness and know that my times, even now, are in your hand. Tune my spirit to the music of heaven, and somehow, make my obedience count for you.”

Unintended pilgrimage. Unlike Brendan and other ancient Irish monks, my sister, brother-in-law, and I were simply on vacation. We were wandering, alright – but it was largely the kind that produced white-knuckle exhilaration and moments of panic while driving 600 miles on the wrong side of the road through the Irish countryside. My sister and I were especially interested in travelling to the Emerald Isle because our maternal and paternal family lines emigrated to the United States from Ireland hundreds of years ago.

Although this was not a pre-packaged spiritual pilgrimage, it was almost impossible to overlook the structural remnants, artistic expressions, and long shadows of 1,500 years of Christianity in Ireland. Blossoming under the seismic spiritual and cultural upheaval introduced by the bold mission of St. Patrick in 422 – all without the use of violence and the sword – Christianity saturated Irish culture. During its heyday between the fifth and the seventh centuries, there were a captivating and colorful cast of saints that included Aiden of Lindisfarne, Brigit of Kildare, and Columba (also known as Colmcille).

Like the stained glass artwork in Dublin, there are missing pieces, broken bits, incomplete details, and yet undeniable beauty in Irish Christian history. Three particular touchpoints made an impression on me.

Kilmacduagh. One of our most memorable brushes with Irish antiquity was discovered accidentally on our way to a tourist-magnet. About an hour away from the Cliffs of Moher – stunning 700 foot sea cliffs on the west coast – we stumbled upon the ruins of Kilmacduagh Monastery near the town of Gort in County Galway. There were no tourists or guides and there was a ghost town silence as we walked around on the loose gravel pathways from one structure to the next and in-between the grave markers of the departed saints buried underfoot.

Among the ancient stone slabs was the final resting place of Saint Colman Mac Duagh (560-632). After spending years in seclusion as a hermit in prayer and fasting, Colman transitioned in his spiritual journey to launch the monastery on this site in 610. In an interesting twist of history for a man who once lived a cloistered existence in a cave, Colman’s gold crozier (a pastoral staff with a curved top carried by a bishop or abbot symbolizing the Good Shepherd) is now displayed in the National Museum in Dublin.

One week after having walked through the ruins of Kilmacduagh, I was more than surprised to find myself face-to-face with Saint Colman in the Dublin City Gallery – one of the few artistic portrayals of the ancient saint. On display was a three-paneled stained glass depiction of Colman’s life from the late Wilhelmina Geddes, another world-class artist. Her illuminated glass work depicted an austere and brooding Colman on his journey from hermit to bishop and monastery abbot.

At the monastery, the skeletal stone remains – a cathedral, three small chapels, a two-story home for the abbot and monks – were built between the 11th and 14th centuries.The ancient slightly-leaning round tower – the tallest remaining in Ireland – is estimated to be from the 12th century. Previous structures had been destroyed. There is an otherworldly rush when you trace the mortar between the stones with your fingertips. I closed my eyes and imagined Irish monks 1,400 years ago walking from morning prayers to milking the cows or off to fix the roof of the chapel or transcribing ancient texts by candlelight.

In 1995, historian Thomas Cahill wrote an international best-seller entitled How the Irish Saved Civilization about the vital importance of monasteries in Ireland that methodically transcribed literature – both sacred and secular – while barbarians were burning irreplaceable manuscripts and poetry in bonfires on the European continent. “Without the Mission of the Irish Monks, who single-handedly refounded European civilization throughout the continent in the bays and valleys of their exile,” wrote Cahill, “the world that came after them would have been an entirely different one – a world without books. And our own world would never have come to be.”

In the last several decades, there has been an eager enthusiasm to learn more about the unique contributions of Celtic Christianity. Many of these books are in my library. But with each step on the gravel pathways, I was simply at peace with a rudimentary affirmation: God moved. God moves. Thanks be to God. Acknowledgment. Expectation. Gratitude.

Belfast, Northern Ireland. Two hundred miles northwest of Kilmacduagh is Belfast, capital of Northern Ireland. Most tourists arrive in search of the world-class Titanic Belfast museum or to explore the natural phenomenon of polygonal rock columns called the Giant’s Causeway on the northern coast.

For the visitor, it is unavoidable to drive through Belfast and not see the graffiti murals that reflect deeply held beliefs about past political and sectarian strife, “the Troubles,” and the underpinnings of reconciliation – or at least a lasting truce to end violence with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

Although usually identified with his teaching posts at Oxford and Cambridge, C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was a son of Belfast. To those who grew up in church, Lewis’s work is most well-known through Mere Christianity and the Screwtape Letters. To those outside the faith (and within), Lewis is the celebrated author of The Chronicles of Narnia, a fantasy allegory filled with deep meaning and higher truth for children. Readers of the tale discover that the entrance for four young siblings into an enchanted and mystical world is through a seemingly ordinary wardrobe.

More than 20 years ago, the Belfast City Council commissioned visual artist Maurice Harron to sculpt characters from the seven-story Narnia series for placement in a square to celebrate Lewis’s story-telling gift. The striking figures portray both the valiant and villainous from the series: Aslan (the lion), Maugrim (the wolf), Mr. Tumnus (the faun), The White Witch, as well as Mr. and Mrs. Beaver.

As I cast an eye upon the majestic Aslan, Lewis’s Christ-figure, my mind replayed the dialogue from the story as the children learn about Aslan. Mr. Beaver tells them, “He is King of the wood and the son of the Great Emperor-Beyond-the-Sea. Aslan is a lion – the Lion, the great lion.”

The older sister, Susan, responds, “Is he – quite safe? I shall feel rather nervous about meeting a lion.” Mrs. Beaver responds, “If there’s anyone who can appear before Aslan without their knees knocking, they’re either braver than most or else just silly.”

“Then he isn’t safe?” asked her younger sister, Lucy.

“Safe?” said Mr. Beaver; “Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.”

Sculptor Ross Wilson created a life-sized Narnian Wardrobe art piece called “The Searcher” for the square. “C.S. Lewis did not just hang clothes in a wardrobe, he hung ideas – great ideas of sacrifice, redemption, victory and freedom for The Sons of Adam and the Daughters of Eve. Set within the commonplace, revelation within something that looks ordinary on the outside – revelation through investigation,” wrote Wilson for the sculpture. “We should not stop looking, some of the greatest things can be found in the most ordinary of places, like a wardrobe.”

For his part, Lewis concluded the final chapter (“Farewell to Shadowlands”) of the Narnia series with an eye on the everlasting. “And for us this is the end of all the stories, and we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. But for them it was only the beginning of the real story,” he wrote. “All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on forever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.”

Dublin. Two hundred years before the Narnia tale was created, Jonathan Swift wrote Gulliver’s Travels – the satirical adventure of Lemuel Gulliver. The tale of faraway kingdoms, giants, scientists, talking horses, and Yahoos captured the vivid imagination of readers in 1726.

Interestingly enough, Swift was also the dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Church of Ireland) in Dublin. The gothic sanctuary is built near a well that is believed to have been used by Patrick to baptize new converts to Christianity. Having grown up in low church Methodism, I still have an awe and fanboy enthusiasm for gothic cathedrals. St. Patrick’s didn’t disappoint.

In the self-guided audio tour, it was mentioned that Swift once preached a four-and-a-half hour sermon. I laughed to myself and was reminded of a story Bono once told about his first visit to St. Patrick’s. Of course, Bono is the Dublin-born singer of the rock band U2, perhaps the most recognizable Irishman on the planet. He also grew up in Ireland looking through the unique prism of having a Catholic father and a Protestant mother.

“How come you’re always quoting the Bible?” asked journalist Michka Assayas in a remarkable set of published interviews with the singer several years ago. “Was it because it was taught at school? Or because your father or mother wanted you to read it?” In response, Bono tells the story of attending a Christmas Eve service at St. Patrick’s and the moment when the incarnation really made sense to him.

During the service, he was jetlagged and sitting behind a huge pillar. “But I was falling asleep, being up for a few days, travelling, because it was a bit boring, the service, and I just started nodding off, I couldn’t see a thing.” But then there was a spark of epiphany. “It had dawned on me before, but it really sank in: the Christmas story. The idea that God, if there is a force of Love and Logic in the universe, that it would seek to explain itself is amazing enough,” said Bono. “That it would seek to explain itself and describe itself by becoming a child born in straw poverty … I just thought: ‘Wow!’ Just the poetry … Unknowable love, unknowable power, describes itself as the most vulnerable.”

The rock star who had become a believer in his teen years described gaining a deeper illumination and insight into an ancient and familiar story. “It’s not that it hadn’t struck me before, but tears came down my face, and I saw the genius of this, utter genius of picking a particular point in time and deciding to turn on this,” he said of the birth of Christ.

“Love needs to find form, intimacy needs to be whispered. To me, it makes sense,” Bono said. “It’s actually logical. It’s pure logic. Essence has to manifest itself. It’s inevitable. Love has to become an action or something concrete. It would have to happen. There must be an incarnation. Love must be made flesh.”

Wandering through a legacy. Ireland has so much to offer the unintentional spiritual pilgrim, but I was most at peace as I sat amongst the flickering candles and stained glass in the stately sanctuary and thought about St. Patrick’s story of being kidnapped as a teenager in Britain and enslaved in Ireland, only to return as a missionary after a mystical dream helped him escape. He stirred up the Irish sense of righteous and heroic adventure – in his case, returning to the place of captivity and preaching liberation and a new way of living together.

For its contribution to Western Civilization, Ireland is singled out as the Land of Saints and Scholars. But that designation is incomplete without the sea farers, story tellers, sculptors, stone masons, stained glass artists, and song writers.

In St. Patrick’s, surrounded by tourists like myself snapping photos, a few lines of a U2 song flittered through my mind: “You’re packing a suitcase for a place none of us has been/ A place that has to be believed to be seen.” For me, there was no better place to be reminded of that hope than wandering around Ireland.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Image: Kilmacduagh Monastery ruins in Gort, County Galway, in the Republic of Ireland. Photo by Steve Beard.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | In the News, Sept-Oct 2022

By Rob Renfroe

I don’t understand those in The United Methodist Church who call themselves “centrists.” I have listened carefully to their claims, but the more I listen, the more questions I have.

First question: Do centrists actually believe that truth is “contextual”? I’ve heard them say the UM Church can have different practices regarding sexual ethics because we are in different contexts. They state in more liberal parts of the country we may marry gay couples and ordain practicing gay persons. In more conservative areas, people may not be ready for the church to adopt those practices, so it’s permissible not to.

But is truth contextual? Missiologists stress the importance of using words and images that present the gospel in a way that is understandable in a given culture/context. But they never argue we should change the message of the Bible to be acceptable to a particular culture. But that’s what centrists are championing – the church may proclaim two contradictory truths at the same time – one affirming same-sex behavior, the other condemning it. Why? Because one view will be accepted in one context and the other in a different context.

Do centrists believe the culture we live in should determine our message? That truth is relative and ethics are situational? That when necessary the church may, and perhaps should, “conform to the pattern of the world” (Romans 12:2), rather than transform the world? The apostles proclaimed a message of sexual holiness that was easily accepted by the Jews of their time. It was the same message they preached to the hedonists in Rome who found the apostles’ views offensive and restrictive. Different contexts. Same message. Why? Because the apostles knew their task was to make the truth plain, not palatable.

Another question: How can centrists state they are staying within the UM Church because UM theology will be uniquely positioned to reach our current culture after the traditionalists leave? Those who believe adopting a progressive sexual ethic will attract secular people to the UM Church and reverse our 50 plus years of decline are either so monumentally naïve that it borders on the miraculous or they are disingenuous.

In 2010 The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America allowed for the ordination and marriage of gay persons. Today the ELCA’s Office of Research and Evaluation projects that the whole denomination will have fewer than 16,000 in worship by 2041. Since endorsing same-sex marriage in 2005, United Church of Christ membership has declined by 30 percent. Since the Presbyterian Church USA re-defined marriage in 2015 as the union of “two people” membership has decreased by 20 percent and youth profession of faiths have dropped by over 50 percent. The Episcopal Church USA approved their clergy performing same-sex unions in 2015. Rather than an influx of secular people to the church, the Episcopal News Service quotes church growth expert the Rev. Dr. Dwight Zscheile, “The overall picture is dire … At this rate, there will be no one in worship by around 2050 in the entire denomination.”

Abandoning the biblical view of marriage has not caused any mainline church to grow. Doing so has only increased the rate of their decline. There is no reason to believe it will be any different with the UM Church.

A third question: How can centrists promise the post-separation UM Church will not become predominantly progressive in its teachings? I know one centrist pastor of a large church who responded by saying, “That won’t happen, not on my watch, I won’t allow it.” I had to laugh.

The Reconciling Ministries Network recently hosted a panel that was asked about their dreams for the future UM Church. One panelist shared his hopes that the UM Church would become a “queer denomination.” Another envisioned a church that includes “every thought, every idea.”

A pastor on the staff of the church I served for over twenty years recently attended a seminar for youth pastors. Led by staff members of some of the denomination’s largest “centrist” churches, he and others were informed that in the future youth leaders would not use the word “kingdom” because it represents God as King – as male. In fact, those leading said we should no longer refer to God as Father. Gender-neutral pronouns would be used for the kids, who would not be divided into groups for boys and girls. This, he was told, was the future of youth ministry in the post-separation UM Church. He was uncomfortable with the presentation, but not as uncomfortable as when the lecture stopped and the entire room stood and applauded. His conclusion was that he and other traditionalists have no place in the future UM Church.

When traditionalists are gone, the pastor who said the UM Church will not go woke on his watch, and others like him – 10 years or so left in ministry, white, in large churches and who are trying to keep the UM Church from becoming thoroughly progressive – will be who we conservatives have been for decades: the enemy progressives see as impeding the march towards justice. They will be surrounded by progressives who care little about their achievements as leaders and pastors because status in the brave new world that will be the UM Church will be gained not by growing a church but by how many “victim boxes” a person can claim, what’s known as intersectionality.

Centrists will not be the driving force of the Post-separation UM Church. Very quickly, they will not be the ones electing bishops or delegates to General Conference. Young, woke progressives will soon be in charge. You may believe the centrists know where the UM Church is going and that they will keep it from going too far. Or you can listen to those who long ago predicted that the church would be right where it is today when we tell you that the future of the UM Church will become more and more theologically and socially progressive until it is unrecognizable as a truly Wesleyan church.

One last question: Would centrists rather be in a denomination that requires its pastors and bishops to be orthodox but would not marry gay persons? Or would they rather be in a denomination that marries and ordains gay persons but allows its bishops and pastors to deny critical Christian beliefs? The UM Church presently has a bishop who has taught that Jesus can be an idol. We have a past UM seminary president who said it’s wrong to tell others about Jesus if they already have a religion. We have pastors who believe that Jesus did not die on the cross to pay for our sins. We have annual conference boards of ministry that will not ordain persons who believe Jesus is the way, the truth and the life for everyone. We have pastors who do not believe in the virgin birth and some who either do not believe in the resurrection or who teach that believing in the resurrection is not essential for Christian faith. This will not change in the future UM Church. It will only increase.

So, my question is this: when did gay marriage become more important to centrists than being in a church that with one voice proclaims that Jesus is Lord; that he is the Savior of the world; that he died for our sins; that he was crucified, dead and buried, but on the third day he rose from the dead?

I know many centrists hold to the most important truths of the Christian faith. But for the life of me, I do not understand the claims they make: truth is not absolute but situational, the UM Church will grow once we codify a liberal sexual ethic, and the UM Church will not become significantly more progressive and woke. And I certainly cannot comprehend how being part of a church that rejects 2000 years of Christian teaching on marriage is more important than being in a church with pastors and bishops who together, as one, affirm the great scriptural truths that define the orthodox Christian faith.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Home Page Hero Slider, Sept-Oct 2022

By David Wilkinson

The first images from the James Webb Telescope were astonishing. A patch of the universe showing objects from which the light started its journey over 13 billion years ago and the distorted shapes of galaxies whose light had been magnified by the gravitational presence of dark matter. Then there was a region of star formation which showed in dramatic relief the dust and molecular hydrogen cloud which is a maternity hospital for newly born stars. And then, if that is not enough, a planet around a distant star with the indication of water molecules in its atmosphere, one of the things necessary for the emergence of life.

Even as someone with a PhD in theoretical astrophysics, the sheer beauty was as jaw-dropping as the multi-billion dollar and three-decade long project which had built, launched, and assembled the telescope to operate one million miles above the earth. And as a Christian this sense of awe naturally turned into worship “as the heavens declare the glory of God.”

However, these pictures of the universe do not lead everyone to belief in a Creator. Science is a complicated business both in its process and its interpretation. While NASA has chosen some awe-inspiring and intriguing first photographs, the hard work of scientists will continue in the background. Science does have its wow moments, but a lot of the time it is tedious, tough, and frustrating. It is about experiments which don’t work, about papers that are rejected by journals, about colleagues who don’t do what you think they should be doing, and about proposals that are never funded!

The long delays of the Webb Telescope, its ballooning budget, and even press conferences which don’t go smoothly illustrate this. Yet scientists continue for the wow moments which show us that the universe is even more spectacular than we thought it was, and for that sense that science is progressing to a tighter description of the reality around us.

The interpretation of science is also complicated, not least in its relationship to belief in God. The media has had many voices who see science and Christian faith as incompatible. Celebrity scientists such Stephen Hawking in The Grand Design, Lawrence Krauss arguing that the Universe came from nothing, and, of course, Richard Dawkins, have all argued that science demolishes the “God delusion.” They argue that science says one thing about the origin of the Universe and the Bible says something different and you have to choose which is correct. Then some say science is all about fact but Christianity is just about faith, implying that faith is a kind of blind belief which bypasses the mind and reasonable argument.

As a scientist and a Christian, I find such voices naïve and somewhat simplistic. That science and the Bible describe the origin of the Universe in different ways does not immediately mean that one is right and one is wrong. Such a conflict model is far too easy and not true to the nature of science and the nature of the Bible.

If I ask why is the kettle boiling I can have two answers. One because heat energy increases the velocity of the water molecules to a point where bubbles form. Two, because I desperately need a cup of tea. One describes the mechanism, the other describes the purpose. Therefore “the Universe came about through a quantum fluctuation leading to a Big Bang,” and “the Universe is the creation of a sovereign God” are for me complementary descriptions of the same reality. Both are true but different.

However, what about the fact/faith opposition? This assumes that science and Christian faith explore the world in completely different ways and are therefore incompatible. But science is a subtle interplay of observations and models, involving human judgment of data and assessment of models. It is based on observations but it is more than that. It thrives on questions but it also involves faith, that is, actions which arise from trust in the evidence.

To launch the Webb Telescope is a huge act of faith. Christianity has some parallels here. I became a Christian because as I read the gospel accounts of Jesus and saw him at work in the life of Christians, I was confronted with evidence which needed to be interpreted. My Christian faith is an outworking of trust in that evidence and the interpretation that this cannot be explained in any other way than this was God in the space-time history of the universe in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus.

As both a scientist and a Christian, faith involves questions, some of which I continue to struggle with, but questions which have always led me to further excitement about both science and Jesus.

The science that will flow from the Webb Telescope will allow us to learn more of the origin of the Universe and perhaps whether we are alone in the Universe. In all of this I don’t want to believe in a “god of the gaps” who simply is rolled in to fill gaps of ignorance. The God whom I believe in is far greater, sustaining all of the physical laws throughout the billions of years of the Universe. The Bible understands that the whole Universe is the result of God’s working and sustaining.

It is fascinating that science does not answer all of the questions. First, “why is there something rather than nothing” is not only a question about mechanism it is also a question about purpose and meaning – the why question behind the Universe’s existence.

Second, where do the scientific laws themselves come from? If the Universe emerges as a quantum fluctuation leading to a Big Bang, we need to ask where quantum theory itself comes from? Where does the pattern of the world come from and how is it maintained? This is not a “god of the gaps” argument, as science itself assumes these laws in order to work. There is a long tradition stretching back to Sir Isaac Newton (1643-1727) who saw the laws of the Universe as the work of the divine lawgiver. “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being…,” Newton wrote in 1687. “The Being governs all things, not as the soul of the world, but as Lord over all; and on account of His dominion He is wont to be called Lord God.” German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) was “carried away by unutterable rapture” as the correlation between orbital periods and mean diameters, which showed that the planets moved in elliptical orbits, was disclosed.

Third, why is the Universe intelligible? In 1936, Albert Einstein said, “The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.” Yet why should this be the case, that the mathematics of our minds resonates with the mathematics of the Universe. Some scientists, including the noted British physicist/clergyman John Polkinghorne, suggest that the natural answer is that there exists a Creator God who is the basis of the order in the Universe and the ability of our minds to understand it.

None of these insights prove to me the existence of God. My own belief in the existence of God and understanding of God’s nature comes from the Christian claim that God revealed himself into the space-time history of the universe supremely by becoming a human being in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. It is from that perspective that I welcome any scientific work on the story of the universe. For me science is a gift from God. As Kepler believed, being made in the image of God allows us to “think God’s thoughts after him.” It is also to be filled with awe at God’s work and to worship this God who creates with such extravagance and joy. So I give thanks for the Webb Telescope, the thousands of scientists and engineers who built it, maintain it, and then interpret its observations. And I look forward to the new questions, puzzles, and insights that it will give us.

David Wilkinson is Principal of St John’s College, Durham University in Durham, England. He is author with Dave Hutchings of God, Stephen Hawking and the Multiverse (Monarch, 2020). Professor Wilkinson is a British Methodist minister, theologian, astrophysicist, and academic. He is a professor in the Department of Theology and Religion at Durham University, has a PhD in astrophysics, and is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Image: NASA: “What looks much like craggy mountains on a moonlit evening is actually the edge of a nearby, young, star-forming region NGC 3324 in the Carina Nebula. Captured in infrared light by … NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, this image reveals previously obscured areas of star birth. Called the Cosmic Cliffs, the region is actually the edge of a gigantic, gaseous cavity within NGC 3324, roughly 7,600 light-years away. The cavernous area has been carved from the nebula by the intense ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from extremely massive, hot, young stars located in the center of the bubble, above the area shown in this image.” Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScl.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Home Page Hero Slider, Sept-Oct 2022

By Thomas Lambrecht

For nearly the last ten years, Good News has advocated for an amicable separation in The United Methodist Church. Following the 2012 General Conference, it became apparent that the different understandings of Methodism could not continue together in one church and remain healthy. That conclusion was only reinforced over the years since that time, with efforts at resolving our differences having failed amid the refusal of many U.S. clergy and bishops to accept the decisions of General Conference.

My colleague Rob Renfroe, president of Good News, has likened our conflicted situation to a cage match, where two opponents are locked in a cage and forced to fight one another until one or the other is defeated. Only then would the cage door be unlocked to let the fighters out. Renfroe’s point was that the cage could be unlocked and the fighting ended without the need for one fighter to lose and the other win, if the denomination were willing to release the trust clause and allow separation to occur.

Leaders from across the theological spectrum arrived at an agreement for such a release in the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation. It promised an end to the cage match of our conflict via an orderly and peaceful separation process. It was negotiated by a mediation team of progressives, centrists, traditionalists, and bishops under the guidance of renowned mediator Kenneth Feinberg, Esq. It provided for central conferences, annual conferences, local churches, and clergy to have a clear way to separate from The United Methodist Church in order to form or join a new Methodist denomination. The costs involved were low, and the process was manageable.

The Protocol still represents the best chance the denomination has of resolving its conflict through an orderly and gracious separation, ending decades of conflict and opening the door to renewed focus on mission and ministry.

None of the Protocol’s signatories or the groups they represent was entirely happy with the terms of the Protocol. But they were willing to sign off on the deal, conceding some terms they did not like in order to gain terms that were favorable and provide for a resolution of the church’s conflict. The focus was on how to amicably end the conflict, knowing that the alternative was to return to the dysfunctional and vicious disputes that characterized the 2019 General Conference.

Unfortunately, it now looks like the Protocol is on life-support. In early June, progressive and centrist leaders withdrew support for the agreement.

All the living signatories to the Protocol representing centrist and progressive viewpoints have signed the repudiation statement. The centrist and progressive groups that had endorsed the Protocol have withdrawn their endorsement, including Uniting Methodists, Methodist Federation for Social Action, Affirmation, Reconciling Ministries Network, UM Queer Clergy Caucus, UMCNext, and Mainstream UMC.

Reasons for backing out. Some of the reasons given in the statement for their repudiation of the Protocol include:

• The passage of time and “long delays.” We, too, are frustrated by the continued unnecessary postponement of General Conference until 2024. It is this delay that caused the Global Methodist Church to be launched. However, many traditionalists have made the commitment to stick with the UM Church in order to seek enactment of the Protocol. One cannot help but wonder if the postponement was part of a plan to provide an excuse for centrists and progressives to withdraw support for the Protocol.

• “Changing circumstances within The United Methodist Church, and the formal launch of the Global Methodist Church in May of this year.” What has changed is that those traditionalist congregations that are able are moving to disaffiliate from the UM Church. Perhaps the centrist/progressive calculation is that such a move will reduce the number of traditionalist delegates at General Conference enough to allow a change in the church’s position on marriage and sexuality to a progressive one. They may be thinking that then there will be no need to allow traditionalists a gracious way to separate.

It would be wise to remember that traditionalists can still hinder the progressive agenda by defeating the Christmas Covenant regionalization of church government, which requires a two-thirds vote. Traditionalists can also refuse to fund a denomination that has turned its back on the clear teaching of Scripture. A coerced covenant is not a legitimate covenant. A church that thinks it can force people to remain in a denomination they do not support is not operating by Christian principles. It is best for all sides to promote amicable separation on reasonable terms to allow agendas supported by all sides to move forward unhindered.

• Serious misgivings voiced by bishops and church leaders in the Central Conferences, concerned about potentially disruptive impacts in their geographical regions. Obviously, the signers of this statement are talking with different bishops and church leaders than we are. Traditionalists heard universal support for the Protocol from our European and African colleagues. Three bishops who attended a recent leadership and prayer summit of the Africa Initiative stated clearly their desire to wait for any decision on disaffiliation until the 2024 General Conference could enact the Protocol. We have been told that if the UM Church adopts a progressive position on marriage and sexuality, there is no way that many African annual conferences will remain in the UM Church, whether they are “allowed” to leave or not.

• “Growing opposition to the Protocol within the constituencies [they] represent [and] dwindling support among General Conference delegates.” One wonders how much these leaders advocated for the Protocol within their constituencies. Most of the progressive and centrist leaders who signed the Protocol seem to have believed that their job was done once their name was on the dotted line and the group photo-op was taken.

Frustratingly, these leaders did not consult with traditionalist groups who have also endorsed the Protocol. Their statement says, “Out of a spirit of transparency, trust, and accountability, members of the mediation team have reached out to the organizations that initially supported the Protocol agreement, General Conference delegates, and others within our broad constituencies.” But they did not reach out to us. There was no transparency, trust, or accountability toward traditionalists.

What Now? While the Protocol may be on life support, it is not quite dead, yet. We believe that new delegates will need to be elected for the 2024 General Conference. It is possible a slate of delegates could be elected that is more favorable to providing for amicable separation, rather than the doctrinaire progressives that were elected in 2019 in reaction to the Traditional Plan. We will await those elections to determine whether the Protocol is a viable path forward.

Other legislative options exist, as well. The General Conference could reinstate para. 2553 of the Book of Discipline (which will have expired by then). The General Conference could also create special provisions for Central Conference members to disaffiliate without going through the arduous, four-year-plus process mandated by para. 572 in the Discipline.

Disassociation blues. With the launch of the Global Methodist Church, more local churches are seeking separation under processes currently available in the Book of Discipline. Good News has asked for and hoped for an amicable and reasonable response to this desire to move forward with separation now. Some bishops and annual conferences have accommodated the need for separation with grace and integrity. Others seem determined to keep the church locked in its cage match indefinitely.

It is important to note that, for decades, bishops and annual conferences have allowed individual congregations to withdraw through a negotiated settlement, sometimes involving the “closing” of the church and reselling the property to the departing congregants. While always a sad occasion, congregational disaffiliation is nothing new in The United Methodist Church.

Faced with the prospect of larger-scale disaffiliations due to deeply held theological convictions, the 2019 General Conference adopted a process for disaffiliation in a new Discipline para. 2553. The intent was to provide a straightforward process that cared for clergy pensions and provided a bit of a transitional cushion for the annual conference through an extra year’s apportionments. While annual conferences could flesh out the disaffiliation process in different ways depending upon their context, the authors of the provision never intended that annual conferences could add financial terms to the requirements. Unfortunately, through a clerical error, the language in the paragraph did not explicitly state that.

Now, some bishops and annual conferences are adding costs that make disaffiliation under para. 2553 so costly as to be prohibitive. Some are demanding a percentage of the congregation’s property value or total assets, anywhere from 20 to 67 percent. Others are demanding reimbursement of any annual conference legal fees. (I have yet to see a reasonable accounting of what legal fees an annual conference might be expected to incur. Such fees should be minimal or nonexistent.) Other conferences are requiring the repayment of any grants given the local church by the annual conference up to ten years or even 20 years in the past (ignoring the benefit the annual conference received in higher apportionment payments in the intervening years due to grant-facilitated congregational growth). At least one annual conference has added just about any costs they could think of, including 18 months’ salary and benefits for the pastor (in case the pastor does not withdraw with the congregation), expenses for two pastoral moves, $500 honoraria for conference-approved representatives to make presentations to the local church extolling the virtues of the UM Church, and more.

To add insult to injury, one bishop is saying that none of that annual conference’s churches can disaffiliate because they do not meet the qualifications of para. 2553, which requires the churches disagree with the General Conference’s position on marriage and sexuality or with the annual conference’s action or inaction regarding those issues. As this bishop is interpreting the situation, a traditionalist church can only leave if its annual conference is in violation of the Discipline, since the denominational position remains in line with a traditionalist position.

Other bishops and leaders are saying that the Global Methodist Church does not qualify as “another evangelical denomination” or as a recognized denomination with which clergy and congregations can unite. They maintain that a denomination must be recognized by General Conference before it fits these descriptions. Never mind that annual conferences receive clergy from dozens of other denominations, including various Baptists, Evangelical Free Church, and others that have never been “approved” by General Conference. All of these actions are purely designed to stonewall traditionalists and delay or prevent separation from occurring.

Alternative Metaphors for Separation. In promoting the idea of amicable separation, Good News has pointed to the examples of Abraham and Lot in Genesis 13 and Paul and Barnabas in Acts 15. In Genesis 13, we read that Abraham and Lot both had large herds and flocks, and that there was not enough room in the land to sustain both of them. Conflict arose between their respective herders. But Abraham told Lot, “Let’s not have any quarreling between you and me, or between your herders and mine, for we are close relatives.” Abraham allowed Lot to choose which part of the land he wanted, and Abraham would take what was left.

Similarly, Good News has said that those wishing to pursue a more progressive agenda could keep the UM Church structure and traditionalists would be willing to withdraw to start something new, rather than attempting to force progressives out of the church against their will. In an effort to resolve our differences in a fraternal way, we advocated for a peaceful, voluntary separation, allowing each group to go its own way. We are not interested in perpetuating the conflict unless forced to do so by not being allowed to separate.

In Acts 15, we read that Paul and Barnabas had a sharp disagreement over whether or not to take John Mark with them on their second missionary journey. Paul did not want to take John Mark because he had abandoned them during their first journey. Barnabas wanted to take him along and give him a second chance. Neither was willing to compromise. So they agreed to go their separate ways. For the sake of the mission of the church, they separated and ended up multiplying the mission. In the same way, Good News has argued that, for the sake of the mission of the church, the two groups should separate and go their own way. Doing so would end the conflict, allowing each group to focus on its mission and ministry, allowing both to become more effective.

Unfortunately, neither of these examples describes some of the more punitive approaches UM leaders are taking. Instead, we find ourselves in a situation more analogous with the conflict between Moses and the Egyptian pharaoh. Moses persistently requested and then demanded that the pharaoh let the people of Israel go. But pharaoh kept hardening his heart and refusing to let the Israelites leave.

Good News has argued that traditionalists need to depart from the UM Church because we worship in different ways, under different theologies, with different understandings of Scripture and even different approaches to our denomination’s governing Book of Discipline.

Unintended Consequences. One thing some UM leaders fail to recognize is that their heavy-handed tactics only serve to make the case for why churches and clergy should withdraw and join the GM Church. Most Methodists do not want to be part of an autocratic church run by power-conscious bishops who impose top-down conformity. Most Methodists do agree with their baptismal promise to resist injustice. Traditionalists are determined to resist the injustice being perpetrated against us by some UM bishops and conferences.

Those promoting a “big tent” Methodism are acting inconsistently with that vision when they attempt to coerce congregations to remain United Methodist against their will. The actions of militant leaders in these days are poisoning any possible future relationship.

It did not have to be this way. We have been and still are prepared to engage in a peaceful, fair separation. We are prepared to follow the model of Abraham and Lot or Paul and Barnabas. But if forced into a corner, we are determined to boldly stand for our understanding of the Scriptures and the Gospel.

It is time to move past this conflict in our church. The Protocol represented the best opportunity to do so in a gracious way. It looks doubtful to pass at this point. There are other options that could lead to a gracious separation, and we will work for them. Even if the separation has to be won through conflict and struggle, we believe in the end it will be worth it.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Image: World renowned mediator Kenneth Feinberg, Esp. volunteered his time and expertise to help progressives, centrists, and traditionalists reach an agreement on a proposal that would maintain The United Methodist Church but allow traditionalist congregations to separate into a new denomination. In June, progressive and centrist leaders withdrew their support of the Feinberg proposal. (Photo courtesy of the Protocol Mediation Team.)

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Front Page News, Sept-Oct 2022

By Kevin M. Watson

Almost all of my writing for the church and the academy has focused in one way or another on the Wesleyan theological tradition. From time to time I am asked: Why are you Wesleyan?

When I was in seminary, I remember experiencing some shock at the wide array of opinions and denominations represented by faculty, students, and the assigned readings. I wrestled with what I was going to do when I graduated and began serving in full-time local church ministry. The models I saw seemed to focus on endlessly exploring ideas across a very broad swath of Christianity. The questions were often good and interesting, but they seemed to always lead to more questions. As someone preparing to pastor a local church, I was pretty sure God was calling me to offer the truth about Jesus Christ and his gospel. I needed to work through the questions to return to truth I could proclaim with confidence to the people God sent me to serve.

I eventually came to a place where I realized the best way I could proclaim the truth was by being deeply anchored in the theological heritage of my particular part of the Body of Christ.

This conviction came as I was taking United Methodist History and Doctrine with Dr. Doug Strong, who would become one of my most important mentors (and my first boss in the academy when he hired me for my first faculty position at Seattle Pacific University).

Doug’s passion for the Wesleyan theological tradition became my passion. He taught Methodist History and Doctrine by anchoring us in the writings of John Wesley. We read Wesley’s sermons and several other occasional pieces he wrote. We studied the basic practices of Methodism. I learned, among other things, that Wesley’s followers were called Methodists because of the methodical pursuit of a particular way of life.

Two things that happened in that class that are crucial for why I am Wesleyan today.

First, I read John Wesley’s teaching on entire sanctification and Christian perfection. I was captivated by Wesley’s optimism of what God can do in our lives through the power of the resurrection of Jesus. I was excited and energized by Wesley’s focus on the importance of salvation and his emphasis on the way of salvation, a journey with God that one grows in with expectation of seeing God deliver from bondage to sin and bring victory in Jesus’s name.

In short, entire sanctification is the Christian belief that the grace of God saves us to the uttermost, freeing us not only from external sins but bringing holy affections, holy tempers. Entire sanctification is loving God and neighbor to the exclusion of sin.

As I’ve spent time with this teaching, I’ve become more convinced that entire sanctification is true. It is powerful! When I speak to leaders in Wesleyan communities, I often say something like this: “There should not be a church in any of your communities that has a more bold and audacious optimism of what the grace of God can do in the lives of every single person in your communities than your church.” My intention in saying this is not to stir up unhealthy and unhelpful competition or strife between denominations. Rather, it is to call the followers of John Wesley back to the riches of their own heritage.

There are two key passages that capture this Wesleyan essential for me. The first is from John Wesley’s sermon, “The Scripture Way of Salvation”:

“But what is that faith whereby we are sanctified, saved from sin and perfected in love? It is a divine evidence and conviction, first, that God hath promised it in the Holy Scripture…. It is a divine evidence and conviction, secondly, that what God hath promised he is able to perform…. It is, thirdly, a divine evidence and conviction that he is able and willing to do it now…. To this confidence, that God is both able and willing to sanctify us now, there needs to be added one thing more, a divine evidence and conviction that he doth it.”

After defining the faith by which we are entirely sanctified, Wesley then asks, Should we expect to receive entire sanctification gradually or instantaneously? This passage gets me every time!

“Perhaps it may be gradually wrought in some … But it is infinitely desirable … that it should be done instantaneously; that the Lord should destroy sin ‘by the breath of his mouth’ in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye. And so he generally does, a plain fact of which there is evidence enough to satisfy any unprejudiced person. Thou therefore look for it every moment…. And by this token may you surely know whether you seek it by faith or by works. If by works, you want something to be done first, before you are sanctified. You think, ‘I must first be or do thus or thus.’ Then you are seeking it by works unto this day. If you seek it by faith, you may expect it as you are: and if as you are, then expect it now. It is of importance to observe that there is an inseparable connection between these three points – expect it by faith, expect it as you are, and expect it now!… Christ is ready. And he is all you want. He is waiting for you. He is at the door!” (John Wesley, “Scripture Way of Salvation”).

The second passage is from Scripture itself, and is one of the crucial passages in Scripture regarding entire sanctification:

“This is the will of God, your sanctification… May the God of peace himself sanctify you entirely; and may your spirit and soul and body be kept sound and blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. The one who calls you is faithful, and he will do this” (1 Thessalonians 4:1-3; 5:23-24).

I am a Wesleyan because I believe that God wants to sanctify everyone who has faith in Jesus Christ and not just a little bit, but entirely! This is God’s will. And God, who calls us, is faithful and will do this!

The second thing that happened to me when I was in seminary that is a major reason I am not only Wesleyan, but got a PhD and became passionate about preparing people for leadership in the church, was that I was invited to join a Wesleyan band meeting. When I was invited, I did not know what it was. But I knew I was in seminary because the Lord had called me to give my life to Jesus and his church and I knew I was moving away from that calling and I didn’t know where to turn.

A band meeting is a small group of usually three to five people focused on confession of sin in order to grow in holiness. It is grounded on James 5:16, “Therefore confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another, so that you may be healed. The prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective.”

Joining a band meeting was one of the hardest things I have ever done. It was also one of the most important things I have ever done. We confessed our sins to one another, not in order to brow beat each other, or to shame one another, but in order to receive forgiveness through the grace of Jesus and in hope and expectation of experiencing healing and transformation.

The highlight of the group was when someone finished their confession and someone else shared words of forgiveness and pardon over them. We often used the words from 1 John 1:9, “If we confess our sins, he who is faithful and just will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.”

My life was changed because of my participation in a band meeting. This led me to study the history of the band meeting in early Methodism. It motivated me to write to help contemporary Wesleyans reclaim this practice, as well as the class meeting. The class meeting was a small group of about twelve people that was required of all Methodists throughout John Wesley’s lifetime and for the first several decades Methodism was a formal denomination in the United States (the Methodist Episcopal Church). The class meeting was less intense than the band meeting, focusing on a question like, “How is it with your soul?”

I am a Wesleyan because I have experienced the fruit of the method of Methodism. I am Wesleyan because I am captivated by the hopeful and optimistic theology which believes that the power of the resurrection of Jesus Christ is greater than sin and even death itself. Even in the times when I have been most discouraged by the state of the contemporary church, I still believe God wants his people to unplug the old wells that were dug by the first Methodists. I am convinced there is still living water there.

One last thing: I am a Wesleyan not because I want to be known as a follower of John Wesley. I do increasingly see John Wesley as the spiritual father of the Wesleyan/Methodist family. But Wesley was not interested in making little John Wesleys. He wanted to help people follow Jesus Christ. I am Wesleyan because it is the best way I know to follow Jesus Christ, to grow in holiness of heart and life.

More than being Wesleyan, I want to be a real Christian. The more I preach the gospel with a recognizable Wesleyan accent, the more effective I believe I will be in following Jesus Christ, my Lord and Savior.

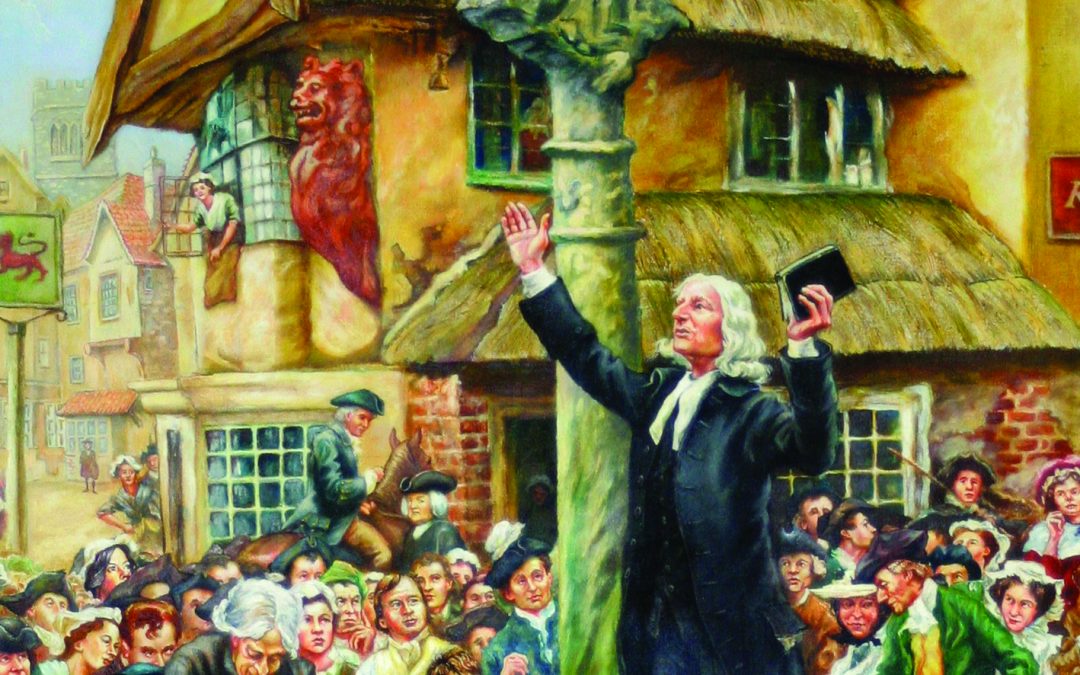

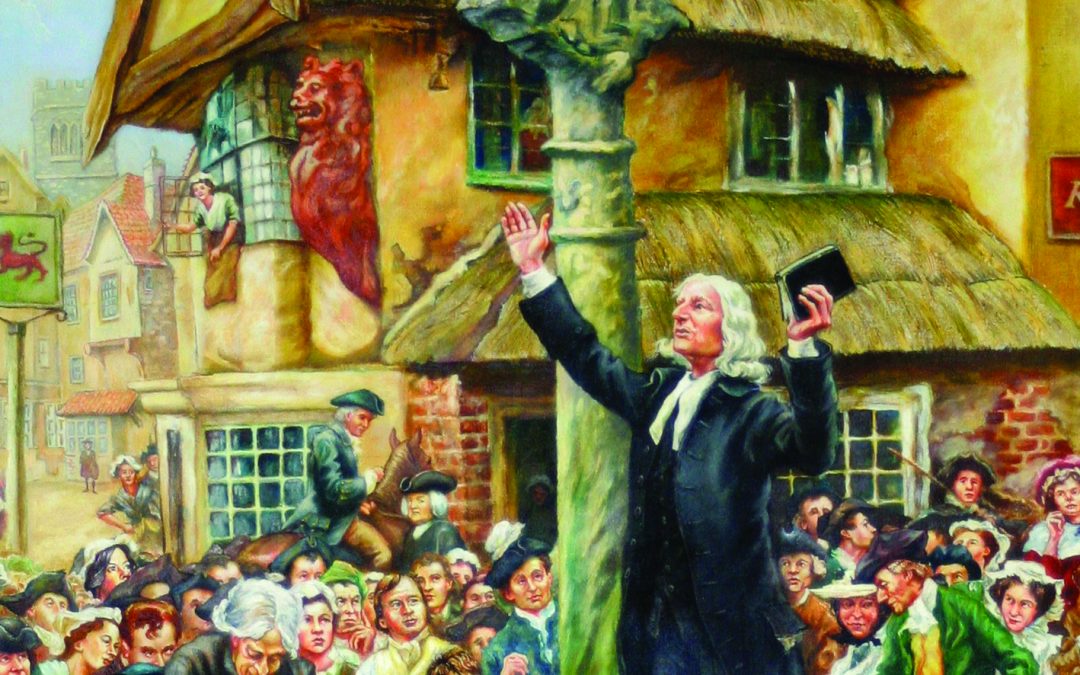

Kevin M. Watson is Acting Director of the Wesley House at Baylor University’s George W. Truett Theological Seminary in Waco, Texas. He is also Associate Pastor of Discipleship at First Methodist Church Waco. Dr. Watson is author of numerous books including The Class Meeting, Pursuing Social Holiness, Old or New School Methodism?, and Perfect Love. Prior to his position at Truett, he served as Associate Professor of Wesley and Methodist Studies at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. Image:

“John Wesley Preaching at the Market Cross” by Richard Douglas. This is a color version of an earlier illustration by William Hatherell (1855-1928). It is part of the Richard Douglas collection of paintings at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Sept-Oct 2022

By Kimberly Constant

The book of Psalms stands at the heart of Scripture as a unique offering in the biblical canon. Whereas the other books of the Bible contain the divinely inspired words of human beings written for the benefit of other human beings, Israel’s ancient book of worship holds the words of human beings written for the benefit of God – words that continue to offer profound insight to modern day believers. The psalms serve as a key to tapping into the deep intimacy inherent in an authentic relationship with God.

When I think of the psalms, immediately Psalm 139 springs to mind. It begins with a beautifully phrased exploration of God’s intimate knowledge and love of the psalmist. Anywhere he goes, there the psalmist finds God. But the psalmist’s words quickly take a dark turn in verse 19 with a call for vengeance against the enemies of the Lord. So stark is the contrast in content and tone that we rightly wonder about its origins. How can such a violent expression of hatred have a place in the Bible? How can these words constitute worship? What do they mean for Christians? Aren’t we called to love? Aren’t we called to make peace? Do such expressions of anger really have a place in our relationship with God?

Surprisingly, the candor of Psalm 139 is not an anomaly. Within the psalter we discover similar calls for vengeance, as well as cries of deepest distress and expressions of anger so vivid that we recoil in shock. These are interposed with more palatable words which speak of green pastures and wings of refuge, or shouts of praise springing forth from all creation, imagery that appears more aligned with Jesus’ call to love God and others. Yet the book of Psalms tells us a story that challenges us to let go of any illusions that such love must only be bright and sunny or that our worship must be sanitized. Instead, the book of Psalms offers us an unflinching representation of the full range of human emotions extended to God as authentic worship.

Truthfully, this is the kind of worship we need at this moment in history in which our collective anger and pain threatens to rip society apart. The book of Psalms offers believers a way through this quagmire, a way to give voice to our deepest feelings as an act of release to God.

The words of the psalms encourage us to rightly rail against the injustices of a fallen and broken world, to genuinely grieve amidst the deep sorrows of life, and to joyously celebrate the victories of faith when they come, but to do so with humility, recognizing our limitations and putting our trust not in ourselves to right these wrongs, but in God. We make room in our hearts so that God can fill us with his divine strength. The very act of reading the Psalms, as words directed to God, allows us to become participants in this kind of genuine worship and relationship.

As we read these ancient prayers and praises, we join with them our own and a holy conversation ensues. So perhaps now is the time to heed the invitation offered by the psalmists – as individuals, but also as a larger community of believers, to commit to incorporating reading the psalms into the daily rhythm of our spiritual practices.

But where to begin? How to make sense of these ancient words? First, with a pledge to engage in a diligent and respectful reading of each psalm on its own terms. To do so we need a general understanding of some features of the psalter. The book contains 150 psalms, which are poems or hymns of worship, divided into five smaller books.

• Book 1 (Psalms 1–41)

• Book 2 (Psalms 42–72)

• Book 3 (Psalms 73–89)

• Book 4 (Psalms 90–106)

• Book 5 (Psalms 107–150)

Although each psalm is unique, we can trace a subtle overarching message in the book of Psalms – a trajectory representative of the evolution of the faith of the Israelites, and hopefully we readers as well.

The psalter begins with two psalms which serve as an introduction for its entirety. They are bookended with the Hebrew word we translate as happy or blessed. Psalm 1:1 attests that the person who delights in God’s ways and is obedient to them will be happy, and Psalm 2:12 closes with the statement that happiness comes when we take refuge in God. These two concepts of obedience and refuge become the means by which the Israelites ultimately will navigate the difficulties that lie ahead. Books One through Three of the psalms thus generally trace the erosion of faith that occurred in Israel during the time of the monarchy, culminating in the somber final verses of Psalm 89, which reflect on the devastation of Israel’s exile and the seeming withdrawal of God’s presence. The response to this national sorrow occurs in books Four and Five, which turn the focus to God as the true king.

Book Four opens with a psalm that is attributed to Moses. The mention of his name mirrors the words of the psalmist in recalling a time in which Israel did not have a human king but instead relied on God alone. Hence the final two books of psalms encourage the people to trust and take refuge in God, rather than any human king or leader, through obedience to God’s law.

Finally, the psalter concludes with five psalms of praise pointing to an ultimate victory for those who remain faithful. Although not every psalm will fit this overarching pattern, determining a psalm’s location within this grand narrative provides a helpful starting point.

Next, the reader might consider the genre of each psalm. Most frequently we encounter laments, often thought of as the backbone of the psalter. Typically, a lament begins with an address, followed by a complaint, a plea for God’s help, an assertion of the psalmist’s trust in God, and a concluding vow of praise. We also find psalms of praise, thanksgiving, psalms which focus on the human king of Israel, psalms which focus on God as king, and wisdom psalms. Some appear to fit into more than one of these categories. Further, some of the identifying features of these psalms are missing or truncated, making categorization difficult at times. Nonetheless, an attempt to identify the genre of an individual psalm helps us understand potentially challenging aspects. For instance, the deep anger in Psalm 139 represents the complaint aspect of a psalm of lament. It is followed by a plea and implied assertion of trust in God in verses 23-24. Having rightly expressed anger at the deep injustice of his world, the psalmist ultimately puts his trust in God and focuses not on his pain, but on his relationship with the Lord.

Finally, as with all poetry, modern or ancient, the form and the function of the psalms also contribute to their meaning. Difficulties abound in this type of analysis due to the elements lost in translation from the original biblical Hebrew. But there are a few features worth noting. One of the more common elements in the psalter is the use of parallelism in which one line of the psalm corresponds in some way with the line that follows. Repeated words or phrases often accompany this device. In addition, the psalms make use of metaphor and simile, hyperbole, and personification. These mechanisms can be a means to capture the reader’s attention, while also allowing the writer a measure of artistry. Often, they highlight the mood and the emotions of the psalmist.

Thus, a conscientious reader can begin a study of a psalm by asking a few basic questions:

1. Where is this psalm located within the overarching narrative of the psalter?

2. What type of psalm am I reading?

3. What stands out in terms of the form, function, or language of this psalm?

4. What mood and emotions does the author invoke in this psalm? Does the psalmist experience a shift in these or does the tone remain the same?

5. Finally, how do all of these illumine the meaning of the psalm?

Lastly, we engage with the psalms through the process of applying our interpretation. Asking ourselves questions such as, “What do I learn about God and God’s work in the world from this psalm?” Or, “How does this psalm lend insight to my role in serving God?” Since the psalms are words directed to God, we might engage in the practice of praying the psalms also, substituting our own prayers and praises when appropriate. Or replacing the psalmist’s “I” or “we” with our own names or the names of those on our prayer lists as we read.

Finally, we would do well to recognize that reading the psalms as a spiritual discipline involves taking the time to savor each psalm. Perhaps reading one psalm in the morning, and one in the evening – as a prayer or devotional exercise, or even listening to it via a Bible app and allowing the words to wash over us. If all of us readers of Good News magazine were to commit to such an exercise, we would read the entire book of Psalms in 75 days. That would be two-and-a-half months of committed reflection, prayer, and worship done in concert with one another and with all the voices of those who have walked the path of faith before us. One can only imagine what God might do, the transformations that might occur, with such an offering of time and commitment.

Ultimately, the psalms encourage us to cultivate a genuine relationship with God, reassuring us that our deepest cries will be met by a God who loves us unconditionally. The God who, according to the psalmist, formed us together in the secret place. The God who spoke the universe into existence. The God who rescued the enslaved Israelites from Egypt and against all odds formed them into a priesthood of believers. The God who continued to extend grace and mercy even when those same people turned from him to pursue their own desires. And as we who live on this side of the cross know, the God who sent us Jesus Christ that we might be free from the chains of sin and death forever.

The world seems on the verge of exploding with anger, confusion, and despair. But we as believers need not meet that fate. Our God beckons us to bring all our feelings to the foot of God’s throne. To offer them up as an act of worship so raw and authentic that all pretense falls away. That in the place of such vulnerability, God might meet us and strengthen us, cultivating within us the deep trust and obedience necessary to genuinely love God and others.

Kimberly Constant is a Bible teacher, author, and ordained elder in the United Methodist Church. You can find out more about Rev. Constant at kimberlyconstantministries. Image: Shutterstock.