by Steve | Nov 22, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2019

By Rob Renfroe –

In six months, the General Conference of The United Methodist Church will meet once again. And once again the business of the conference will be consumed with our differences regarding sexual ethics.

In six months, the General Conference of The United Methodist Church will meet once again. And once again the business of the conference will be consumed with our differences regarding sexual ethics.

Various groups have filed their plans for a way forward. What these plans reveal is that, after a special General Conference was held to determine The United Methodist Church’s position regarding marriage and ordination, nothing has been resolved. The church’s traditional, biblical sexual ethic was reaffirmed; but many progressives and many of those who call themselves “centrists” have been unwilling to live by the church’s position and are gearing up to defeat it in Minneapolis.

The preference of Good News and our partners in the Reform and Renewal Coalition is a fair and respectful separation that ends the fighting. Before and after the special Conference in St. Louis, we have been in many conversations, looking for “centrist” and progressive leaders who agree that we need a solution that has no winners or losers and that allows all of us to pursue ministry to the world as we believe God has called us to do.

Thankfully, we have found some nontraditionalists who have been willing to work with us. Some even helped to craft The Indianapolis Plan. While not a perfect plan, it achieves a form of separation we can gladly support. The “centrist” and progressive leaders within the church who have chosen to work with us in this endeavor are sincere pastors and laypersons who believe that continued fighting will harm their local churches and The United Methodist Church’s witness to the world. They have concluded, as we have, that a fair and respectful separation honors Christ and does the least harm to his body.

Sadly, however, most high-profile “centrist” leaders reject such a solution. It’s hard to understand why. At General Conference 2016 in Portland, the Rev. Adam Hamilton publicly stated the only solution he could envision for ending our stalemate regarding sexuality was to create three new churches. He made this statement to a group of seminarians who were observing the Conference after he attended four lengthy meetings with traditional, progressive, and other centrist leaders.

I participated in those meetings, and I can report that with the exception of the bishops who did not share their personal views, everyone in those meetings agreed that it was time for separation. Of course, the Rev. Hamilton and some of the other centrist leaders in those meetings, led the charge to defeat plans for amicable separation less than three years later when we met in St. Louis.

Other centrist leaders in closed-door meetings since St. Louis have stated to me that it’s time for a respectful parting of the ways. But, publicly they are opposing every plan that resolves our differences without winners and losers. Their amicable separation is: “Centrists win. Traditionalists leave.”

At the Church of the Resurrection’s annual Leadership Institute, the Rev. Hamilton told those gathered, “We are going to remove from the Book of Discipline the language that is harmful to human beings, the policies that are continuing to to bring harm to the LGBTQ community….” In other words, the “centrist” plan is to put us through the ugliness and the pain of St. Louis, once more, with the hope that this time they will win. And when the church’s traditional sexual ethics have been reversed to embrace same-sex marriage and the ordination of practicing gay persons, Hamilton believes conservatives will depart. In the same speech he estimated that between 3,400 and 6,800 traditional churches would leave the denomination.

Regrettably, the strategy behind the plan that most well-known “centrist” leaders support is: “We win. Y’all leave.” Their plan is not a separation of equals but an exodus of those who hold to the church’s historic teaching on marriage and sexuality.

I had hoped we were beyond this point. Good News has for years argued that it is time to create a solution that stops our dysfunction and that has no winners or losers. It is time – past time – to conclude that a “winner-take-all” or a “winner-take-most” approach is beneath us and is unhelpful in resolving our differences.

Those behind the “centrist” strategy have been persons who in the past we looked to as voices of reason. We disagreed with them on sexual ethics, but we found we could have honest dialogue with them and we believed we all had the good of the church in mind. But when offered a way forward that is fair, amicable, and respectful, their preferred approach appears to be an abrasive and harmful fight they believe they can win. And at that point, they are sure, they will not have to offer traditionalists much to leave.

Who will prevail in Minneapolis? A coalition of traditionalists and lesser-known progressives and “centrists” who want to end the fighting and separate? Or high-profile “centrist” leaders who promised their followers a victory in St. Louis and who are willing to fight the same ugly battle again because, “trust us, this time we really can win”?

If amicable separation is defeated, the Reform and Renewal Coalition has also filed legislation that will complete and strengthen the Traditional Plan. It is not our preferred solution because it will not resolve our differences, stop the fighting, or bring unity to the church. St. Louis proved that. But it will be on the table in Minneapolis.

I am reminded of lines from a Robert Frost poem: “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.” We have traveled the same path for many years, really decades. It has led to acrimony, disobedience, dysfunction, and decline. It’s time to choose a path that will make all the difference.

by Steve | Nov 22, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2019

The Wesleyan Way to Read Scripture

By David F. Watson –

Last semester I taught a class called Wesleyan Biblical Interpretation. We read a considerable number of Wesley’s writings along with a couple of secondary texts. Rereading these primary and secondary sources led me to ponder anew the vast differences between the way in which Wesley read the Bible and the critical stances that emerged during and since the European Enlightenment.

Wesley did engage in some of what is called “lower criticism” – criticism of the biblical text in order to render the most accurate manuscript possible. He also at times offered translational corrections to the King James Version. Wesley would have balked, however, at the skepticism that came to characterize what is called “higher criticism,” or historical-critical readings of the Bible.

For Wesley, the way in which the church had interpreted a passage of Scripture through the centuries was in large part determinative of that passage’s meaning. In other words, the church’s consensus helped to establish the plain sense of the text. Reading the Bible was not simply an individual undertaking. It was an ecclesiastical undertaking. In fact, without the guidance of the church, it was not possible to understanding the Bible correctly. For Wesley the Bible had one purpose: to lead us into salvation, and therefore reading it apart from the church’s theology of salvation would be futile.

Historical Criticism. Even during Wesley’s lifetime, however, the seeds of historical criticism were beginning to sprout, and soon they would grow into a dense forest of interpretive skepticism. For the historical critic, the consensus of the church is far more likely to impede proper interpretation than to facilitate it. For one thing, the argument goes, the orthodox faith of the church depends upon an ancient worldview that is supposedly no longer believable to the modern mind. Modern people simply don’t believe in miraculous healing, the multiplication of food, angels, demons, and the like.

Further, according to the historical-critical method, the theological readings of Christians represent developments that are in many ways foreign to the text. The real meaning of the text is controlled by historical context. Only when we have clearly established the historical context of a biblical text can we begin to discern its meaning. The purpose of the Bible, for historical critics, is not to lead us into salvation, but to reveal the historically conditioned perspectives of ancient Israelite, Jewish, and Christian communities. To the extent that the Bible can inform the life of the church, it does so based upon the meaning derived from historical context.

The historical-critical approach long dominated seminary education. Of course, many scholars have adopted some of its presuppositions and interpretive strategies a la carte. I’d put myself in this camp. Historical context does matter in biblical interpretation. Yet I’ve rejected the skepticism that has tended to inhere within historical-critical approaches. I do not, moreover, limit the meaning of a text to its historical context. I believe there is real value in the ways in which Christians have interpreted texts theologically over the centuries.

Postmodern Approaches. To some extent, reliance on the historical-critical method has abated in seminary education. The modernist historical-critical approach has given way to postmodern readings that locate meaning in social location and identity. There are, for example, African-American, Korean, feminist, and queer readings of Scripture. Far from the originalist inquiries of the historical critics, these approaches emphasize the ways in which the text takes on a life of its own within particular communities today. A common (though not universal) feature of postmodern readings is a “hermeneutics of suspicion.” Rather than the skepticism of modernist interpreters, many postmodern interpreters approach the Bible as a source of coercive power that has been used to control, oppress, and harm.

Wesley’s reading has more in common with these postmodern approaches than with historical-critical method because he did not aspire to critical detachment from the text. Though Wesley did at times take into account the historical settings in which the biblical texts were written, he read them in specifically theological ways. His reading was conditioned by, among other perspectives, the worldview and values he derived from the Great Tradition of Christian faith, the Church of England, German Pietists, and the evangelical Methodist movement.

A Hermeneutics of Trust. Nevertheless, Wesley would have been as uncomfortable with some postmodern approaches as he would have the skepticism of the historical-critical method. His reading of the Bible was characterized by what we might call a “hermeneutics of trust.”

Wesley trusted the Bible. Or to be more precise, he trusted the God who had given us the Bible, and therefore he regarded the Bible as trustworthy. He realized that there were passages that one could not interpret literally. He believed that there were passages that, when taken at face value, presented the reader with an absurdity. He also understood that it was possible to use Scripture in ethically irresponsible ways (such as in support of the slave trade). He dealt with such matters as best he could (as we all do). The key to understanding Wesley’s hermeneutics of trust is to understand that his true north when reading Scripture was salvation. The Bible was the book that God had given us in order to teach us how to be saved – how to live in keeping with God’s will in this life and live with God eternally in the next. Any reading that did not lead to salvation was in fact a misreading.

Wesleyans and the Bible Today. It has been both spiritually edifying and intellectually interesting to look at Scripture through Wesley’s eyes. I’ve never been comfortable with a primary stance of either skepticism or suspicion. In part this is because, like Wesley, I believe that a good God has given us Scripture for our salvation. Scripture teaches us how to live well in this life and to live eternally with God.

Part of what is at stake for me in this conversation is vocation. There is a difference between a scholar and a scholar of the church. My work is in and for Christ and his church. It is in service to a saving faith in Christ that has been passed down from generation to generation through the church. To attempt to serve Christ’s church while separating her faith claims from her sacred text is an exercise in futility. It was that very faith that gave rise to the development of those texts. I haven’t jettisoned the tools I was given in my training as a biblical scholar, but neither have I retained all of the assumptions that so often accompany the use of those tools.

As cultural Christianity in the West collapses, however, the question of how scholars interpret the Bible in and for the church is going to become more acute. Churches are going to have think more self-consciously about their relationship to an increasingly anti-Christian academy. They are going to have to identify more precisely what they want from their scholars and seminaries. They are going to have to identify the relationship of skepticism and suspicion to the church’s evangelistic mission of making disciples of Jesus Christ.

Of course skepticism and suspicion can help us with regard to intellectual and moral self-examination. But what happens when our analysis of the Bible is characterized more by skepticism and suspicion than by trust? It seems then our relationship to the Bible will be one primarily of antipathy.

The people called Methodists would do well to attend more fully to the emphases of our founder as he approached the Bible. We could use more trust, more theology, more doctrine, and more prayer in our reading. Skepticism and suspicion aren’t going away, nor should we attempt to silence them. Yet neither should we give them a place of privilege as we read the church’s book.

David F. Watson is the academic dean and professor of New Testament at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. This article first appeared on his blog and is reprinted here by permission. Dr. Watson is the author of Scripture and the Life of God (Seedbed)

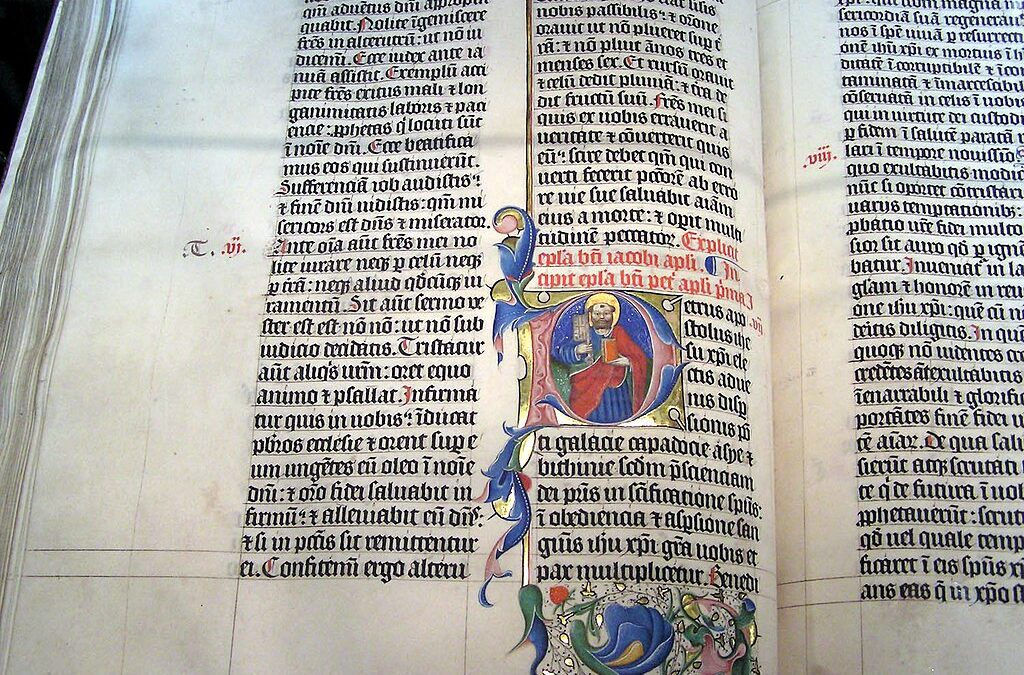

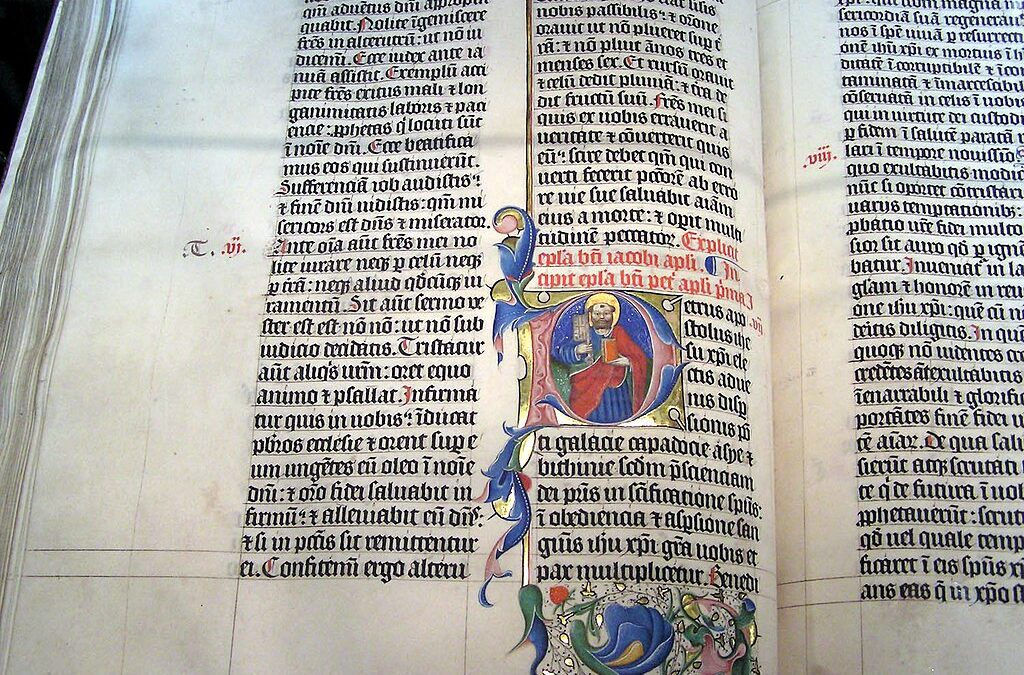

Art: Illuminated lettering in a Latin Bible of 1407AD on display in Malmesbury Abbey, Wiltshire, England. Wikipedia Commons.

by Steve | Nov 22, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2019

By James V. Heidinger –

Stained glass image of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. In 1930, Bonhoeffer arrived at Union Theological Seminary in New York City in the midst of major theological tensions between those who affirmed “new theology” and those who held to traditional faith. Photo: Tomasz Kmita-Skarsgård, Creative Commons.

In an ironic twist of fate or providence, it was a Jewish scholar who helped spark the intellectual and doctrinal renaissance in Dr. Thomas C. Oden (1931-2016), the pre-eminent Wesleyan theologian of our modern era.

Will Herberg was a world class sociologist of religion and the author of the acclaimed text, Protestant, Catholic, Jew. He was also a forthright friend and colleague of Oden’s at Drew Theological School. The two were faculty members for more than 30 years, having become friends during Oden’s first year as professor there in 1970. They shared frequent luncheons and conversations over tea.

“Tom, if you are ever going to become a credible theologian instead of a know-it-all-pundit, you had best restart your life on firmer ground,” Herberg challenged Oden one day. “You are not a theologian except in name only, even if you are paid to be one.” That remark pierced Tom’s heart. And it changed his life. Oden’s great “theological reversal” began as a result of that conversation and friendship, an account he writes about in his book, A Change of Heart: A Personal and Theological Memoir (Intervarsity Press).

In his academic work, Herberg wrote at length about a great “religious belonging and identification” within American Christianity in the 1950s. Church membership and Sunday school enrollment were at historically high levels, and church construction was booming. Bibles were distributed in record numbers, and he observed that 80 percent of the populace thought the Bible was the “revealed word of God.” (The 80 percent was for the “populace,” not the clergy.)

Surveys during this period showed “belief in God” to be nearly universal, but Herberg asked what this “belief” really meant. Half of those surveyed could not name even one of the four Gospels. He then added a penetrating observation about American faith in the 1950s: “It is thus frequently a religiousness without serious commitment, without real inner conviction, without genuine existential decision. What should reach down to the core of existence, shattering and renewing, merely skims the surface of life, and yet succeeds in generating the sincere feeling of being religious.”

A shallow religious faith that lacks commitment and inner conviction is the opposite of a robust faith grounded in scriptural teaching. Herberg points out that many factors may have played into this strong drive to embrace some sort of religious faith but “to wear it lightly.” He cited the ending of the global threat of World War II followed quickly by another in Korea, a healthy post-war economy with its temptations toward materialism, etc. But the question must be asked about those years, was the Christian faith being taught during the 1950s grounded in sound biblical teaching?

This is a critical question. The clergy leading the American churches during the 1950s would have been taught during the era beginning in the 1920s. In those years, many seminaries and professors had likely embraced the popular new wine of theological liberalism, or the “new theology,” as it was called.

What was the “new” theology? Theological liberalism was the movement that endeavored to accommodate the Christian faith to anti-supernatural axioms that had become widely accepted in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Powerful intellectual movements – the new science, social Darwinism, and the influence of German rationalism – swept across the country during this era. In the midst of this intellectual tsunami, theological liberalism emerged. It was American Protestantism’s attempt to accommodate its Christian teachings to this suddenly popular intellectual movement. As one might imagine, the new secular, anti-supernatural emphases had an eviscerating influence on America’s seminaries and churches during those years.

Alister McGrath, former professor of theology at Oxford and more recently at King’s College London, wrote about theological liberalism: “Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the movement is its accommodationism – that is, its insistence that traditional Christian doctrines should be restated or reinterpreted in order to render them harmonious with the spirit of the age.”

And that happened, both in American Methodism as well as other mainline Protestant denominations during those early decades of the 1900s. (For a fuller account of the impact on American Methodism, see my book, The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism (Seedbed)). The result of this accommodation was a move away from the supernatural aspects of the faith, with an enthusiastic preoccupation with the ethical teachings of Jesus.

Surprisingly, doctrines such as the virgin birth, the resurrection of Christ, the ascension, and the promised return of Christ had become difficult for many pastors and theologians to affirm amidst the exhilarating and supposedly liberating views of the new scientific and evolutionary world view. As a result, the great creeds of the Christian faith (the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds, etc.) were deemphasized, their usage even put aside for the more supposedly relevant “Social Creed of the Churches.” Pressing social needs in America’s urban centers made it easy to justify a passionate new focus on ethics and building the kingdom of God on earth – or “Christianizing society” as it was often called.

Adding to the popular new social emphasis was its convenient avoidance of the supernatural doctrines of traditional Christianity, which had become something of an embarrassment to churches that were supposedly “coming of age” intellectually. These developments may help us understand, at least partially, what happened to the spiritual vitality of America’s churches in the 1950s. Two brief vignettes may help illustrate.

Bonhoeffer at Union Seminary. In September of 1930, German pastor and future martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer came to study at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He was not your typical theology student. After all, he already had an earned doctorate from Berlin University and had studied under Adolf von Harnack, a renowned liberal theologian in Germany. While Bonhoeffer did not agree with many of Harnack’s conclusions, he respected his serious scholarship. In fact, scholars differ about the orthodoxy of Bonhoeffer’s doctrinal views.

Bonhoeffer soon learned that he arrived in America in the midst of major theological tensions between those who affirmed the “new theology” and those who held to the traditional faith – call them orthodox, traditionalists, essentialists, or fundamentalists.

At Union, Bonhoeffer found the theological situation worse than he had anticipated. “There is no theology here…. The students – on the average twenty-five to thirty years old – are clueless with respect to what dogmatics is really about,” he wrote. “They are unfamiliar with even the most basic questions. They become intoxicated with liberal and humanistic phrases, laugh at the fundamentalists, and yet basically are not even up to their level.”

While he acknowledged several basic groups, he noted that “without doubt the most vigorous … have turned their back on all genuine theology and study many economic and political problems. Here, they feel, is the renewal of the Gospel for our time.” While he felt the students showed admirable personal compassion for the unemployed over the winter season, still, he added, “It must not, however, be left unmentioned that the theological education of this group is virtually nil….”

Bonhoeffer was equally disillusioned about the American churches, especially in New York City. “The sermon has been reduced to parenthetical church remarks about newspaper events,” he wrote. “As long as I’ve been here, I have heard only one sermon in which you could hear something like a genuine proclamation.” He went on to ask, “One big question continually attracting my attention … is whether one here really can still speak about Christianity?”

With the exception of several impressive African-American churches, Bonhoeffer’s church experience was deeply disappointing. “In New York they preach about virtually everything, only one thing is not addressed, or is addressed so rarely that I have as yet been unable to hear it, namely, the gospel of Jesus Christ, the cross, sin and forgiveness, death and life.”

What had taken the place of the Christian message? According to Bonhoeffer: “An ethical and social idealism borne by a faith in progress that – who knows how – claims the right to call itself ‘Christian.’” Keep in mind that this indictment did not come from an American evangelical or fundamentalist. Instead, these were the reflections of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who would become a respected pastor, theologian, author, and martyr of the German Church under Hitler. Union Theological Seminary was no doubt considered at the time to be on the cutting edge of new theological trends. Its students would have been considered future leaders of the church. But what would be the substance of their preaching and teaching? To Bonhoeffer, they were “clueless” about theology.

One senses there must be a connection between what Bonhoeffer experienced and Herberg’s observation about America’s 1950s religiosity that was frequently “a religiousness without serious commitment, without real inner conviction, without genuine existential decision.” Seminarians who are “clueless” about theology and are caught up in merely social and political matters are woefully unprepared for local church ministry. We would assume that the embracing of the “new theology” Bonhoeffer found at Union would not be too unlike that found at other mainline Protestant seminaries across America during that period.

Gilkey in Texas. In July of 1944, James G. Gilkey was invited to be the main speaker at a Texas Pastors’ School for Methodist clergy at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. At the time, Gilkey was the popular pastor of South Congregational Church in Springfield, Massachusetts. The invitation was notable because Methodist pastors’ schools would draw 300-400 clergy as a continuing education event.

Well-known evangelical Methodist pastor Robert P. Shuler protested the Gilkey invitation, claiming Methodism was offering a podium and legitimacy to teachers who were experts in the denial of the basic doctrines of classic Christianity.

Shuler called attention to Gilkey’s book, A Faith to Affirm, in which the Congregational pastor did not hesitate to state the “new doctrine” he had embraced. Speaking about what “we liberals” believe, Gilkey claimed Jesus was born in the normal way, the eldest child of Joseph and Mary; that the miracles attributed to him are in reality legends which sprang up during and after his life; his most important act was not to die on the cross, but to live and teach our race its most significant set of religious and ethical beliefs; and that his soul or spirit was resurrected, not his body, and it still continues on in some further realm of existence.

After this litany of denials, Gilkey went on to write, “We cannot think that by dying Jesus purchased for human beings forgiveness of sin: to us Jesus’ death is tragedy, nothing more.” All he had left of Christianity were the teachings of Jesus. This, of course, was a central characteristic of theological liberalism. He wrote, “We Liberals regard them [the teachings of Jesus] as the most precious elements in Christianity; and we propose to take them, combine them with new truths and insights gained since Jesus’ time, and then offer this combination of teachings to the modern world as a new form of the Christian faith” (emphasis mine).

One gasps at such assertions. Little wonder there were protests at Gilkey’s invitation to speak. (More can be read about this in Theological Liberalism.)

Skimming the surface of life. In the early decades of the 20th century, theological liberalism flourished in America while serious biblical study languished. The “new theology” urged the Church to put aside the controversial supernatural aspects of Christianity and focus instead on the moral and ethical teachings of Jesus. Certainly, not all adherents of theological liberalism would have accepted all the doctrinal denials. No doubt some clergy wanted to be perceived as liberal and modern, but yet held to some traditional understandings of the faith, perhaps more out of nostalgia than deep conviction.

Theological liberalism brought a very different understanding of historic Christianity. It changed drastically the churches’ proclamation as well as the substance of theological education during this period. Things supernatural were out.

The Gilkey vignette, like that of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, may help us understand why the American church, which enjoyed such robust numbers in the 1950s, was described by Herberg as displaying a religiosity “without serious commitment, without real inner conviction, (and) without genuine existential decision.” This was a religious faith, he observed, that “merely skims the surface of life.”

One wonders what the clergy of those days had been taught in their seminary education. In many American seminaries, things supernatural had been set aside for the new emphasis on the social teachings of Jesus. Such a change would have had enormous implications for the churches’ proclamation. And what about the laity hearing this “new doctrine?” Church members would have been reluctant to make a “serious commitment” with heart-felt “inner conviction” to a set of social and ethical teachings, as noble and helpful as they might be.

What we know is that a message centered on “an ethical and social idealism borne by a faith in progress” (Bonhoeffer’s observation), and a message of Jesus’ “social teachings combined with new truths and insights” (Gilkey’s proposal) are not worthy substitutes, singularly or together, for the “faith that was once for all entrusted to the saints” (Jude 3). Little wonder the mainline churches languished.

James V. Heidinger II is the president emeritus of Good News and the author of author of several books, including The Rise

of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American

Methodism (Seedbed).

by Steve | Nov 22, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2019

By C. Chappell Temple –

“So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27). Facade painting from 1647 with Adam and Eve in Graubunden, Switzerland.

After more than forty years of discussion and debate, it’s clear that United Methodists are more divided than ever over how the church should respond to questions relating to homosexuality and same-sex marriage. Far too often, however, the arguments advanced by many on both sides have been unduly caustic and even shrill in their expression, “full of sound and fury signifying nothing,” as Shakespeare once expressed it.

It is for that reason that I recently entered into a somewhat public pastoral conversation on the topic with a friend and colleague from my annual conference who sees these important issues differently than I do.

Our experience as pastors in the local church helped frame the question in personal and not simply theoretical or even theological terms. I’ve also counseled with numerous individuals and families on the issue, including several young men with whom I was privileged to walk through the AIDS crisis in its early years. My current congregation is composed of individuals from across the spectrum and with clearly distinct and different perspectives and orientations. Like my colleague, I have tried never to speak on the issue without keeping in the front of my mind the gay and lesbian friends I have made both inside and outside of the church over the decades.

As United Methodists we are all, hopefully at least, “people of the Book,” as John Wesley similarly called himself a homo unius librius, or a “man of one book.” The distinction for most comes thus not over acknowledging the inspiration of the scriptures, and thus their authority in our lives, but rather in exactly how we are to interpret those words, specifically as they speak to the question of human sexuality.

The place we must start is with what the Bible actually has to say about this, whether we may happen to agree with it or not. After all, as the Rev. Bill Bouknight once quipped, the liturgical response that we make on Sunday mornings is “This is the Word of the Lord… Thanks be to God,” and not “This is the Word of the Lord…are you okay with that?” So how are we indeed to make sense of the scriptural witness?

We must begin by acknowledging that the question of same-sex behavior is not a prominent biblical concern, at least insofar as specific textual references are involved. The question is not addressed in the Ten Commandments, for instance, nor are there a large number of passages in the Bible that bear directly and certainly on same-sex behavior. Jesus never mentions such conduct. Jesus also did not speak out about child abuse or nuclear war – but most Christians have inferred that he would have opposed them. More significantly, the Lord never addressed the primary social dysfunction of his own time, which was slavery. We have rightly assumed that had he done so, however, he would have said that it was wrong and a violation of the divine image God has placed inside each of us.

Misusing Scripture: Slavery and Women. It has often been suggested that the biblical perspective on homosexuality can indeed be likened to how the scriptures were misused in earlier times to justify slavery. But even given the fact that slavery in the ancient world was far different indeed from the chattel model in the American experience, still, the admonitions for slaves to obey their masters were always matched by a word mitigating how masters ought to treat those under them, whether they were a slave or simply a servant (doulos).

Despite how some in the past attempted to justify the practice, it would be a far stretch indeed to say that the scriptures were truly pro-slavery. In the New Testament, Paul’s letter to a slave owner named Philemon about his runaway slave Onesimus, for example, the apostle instructs Philemon to receive Onesimus “no longer as a slave… but as a dear brother,” even encouraging Philemon to “receive him as you would receive me.”

As Dr. Gavin Ortlund points out, Paul “dissolves the slave/master relationship, and erects in its place a brother/brother relationship, in which the former slave is treated with all the dignity with which the apostle himself would be treated. Thus, even before the actual institution of slavery is abolished, the work of the gospel abolishes the assumptions and prejudices that make slavery possible.”

Similarly, to take another supposed parallel, the particular passages that some used as prooftexts for the subjugation of women, including the prohibition against ordination in the church, never actually told the whole story, either. For as early as the period of the judges in Israel, there were examples of women such as Deborah in leadership, a pattern which continued into the New Testament in both the role of women in the early church but more significantly in the way in which Jesus himself elevated women in his interactions with them

However polemically helpful, we may suggest that the attempt to draw a parallel to slavery and women’s rights with that of countering homosexual behavior is thus misleading. It is worth observing that out of all the references to intimacy within the scriptures, reflecting millennia of moral development, there is not a single positive reference within the Bible to same-sex behavior. What’s more, even if the texts regarding same-sex behavior are limited, they are sufficient enough to establish a consistent biblical outlook on the matter, especially when they are viewed within the broader context of the scripture’s teaching on human sexuality in general. For a biblical view of this issue is not to be drawn only from a list of prohibited activities, but also on the pervasiveness and reasonableness of an affirmed activity, that is, marriage between a husband and wife.

Should we ignore Leviticus? There are two well-known and oft-cited passages regarding same-sex behavior in the Old Testament, Leviticus 18.22 and 20.13. The principle line of argument used to negate the significance of these words for Christians today, however, has been to note that these verses are part of a system of cultic taboos within early Jewish culture known as the Holiness Code, a code which some will say was of purely human origin, or at best, principles intended for one specific context, but not expressive of the mind of God or his timeless design for us.

Those who would wish to apply these words to modern circumstances must therefore recognize that within the surrounding chapters there are also prohibitions against eating shellfish, for example, and even against cross breeding cattle, cross-planting crops, and cross-sewing two different kinds of fabric onto the same garment. If we’re not going to follow all of those regulations, or wish to understand them as simply a temporary code of conduct during the Wilderness years, then, so the argument proceeds, we ought not to pick out a few verses, such as these two, for selective enforcement either. More significantly, it has been suggested that the Leviticus texts are in actuality a condemnation not of same-sex behavior itself, and certainly not of the kind of long-term loving relationships which may exist between two men or two women, but specifically of male prostitution which marked the pagan and foreign cults of many of Israel’s neighbors at the time.

The problem with this argument, however, is that the New Testament reaffirms the validity of the Old Testament warnings about homosexual behavior, suggesting that the prohibitions were not simply part of the ceremonial laws which were only for a certain time and situation, but they were a part of God’s everlasting moral laws with a continuing ethical significance. To dismiss all of this portion of God’s Word out of hand is to plainly do injury to the idea of inspiration as well as sound interpretative principles. Indeed, even a casual glance makes clear that the Ten Commandments themselves are recorded in Leviticus 19 – directly between these two texts in question.

What is plain is that the Bible does not forbid homosexuality per se – that is, the state or orientation of an individual – but it speaks to homosexual behavior. A person who is a homosexual might not ever express that orientation in actions, choosing to embrace celibacy, for instance, while in contrast, another person may engage in homosexual actions even if they self-identify as heterosexual.

Classical World. There are those who suggest that loving and monogamous same-sex relations were relatively rare in the first century and that the biblical admonitions addressing such are not applicable to today’s situation. This is to ignore that there were clearly such consensual relationships between adults in the classical world. Four centuries before Paul, for instance, Plato, Aristophanes, Phaedrus, and Pausanias all give a positive view of same-gender eroticism, with Aristophanes writing of male partners “who continue to be with one another throughout life … desiring to join together and be fused into a single entity,” becoming “one person from two.”

As biblical scholar N.T. Wright observes: “As a classicist, I have to say that when I read Plato’s Symposium, or when I read the accounts from the early Roman empire of the practice of homosexuality, then it seems to me they knew just as much about it as we do. In particular, a point which is often missed, they knew a great deal about what people today would regard as longer-term, reasonably stable relations between two people of the same gender. This is not a modern invention, it’s already there in Plato. The idea that in Paul’s today it was always a matter of exploitation of younger men by older men or whatever … of course there was plenty of that then, as there is today, but it was by no means the only thing.”

Indeed, the ancients even offered theories to explain same-sex attraction, and as Dr. Robert Gagnon has commented, some of their views sound “remarkably like the current scientific consensus on homosexual orientation.” It is worth noting as well that according to the Roman historian Suetonius, the emperor Nero had at least two public wedding ceremonies to other men, in one of which Nero wore a veil and played the role of the bride. Rather than being merely reflective of the culture in which he wrote, Paul’s commands were thus actually quite counter-cultural. And his views reflected not just Greek and Roman thought, of course, but centuries of Jewish tradition as well, suggesting his assent indeed with the very Old Testament texts which we have considered.

Transformation. The Apostle Paul’s primary text regarding same-sex behavior is found in the first chapter of Romans. The larger argument within the first three chapters of Romans is clearly that the Gentiles as a whole have repressed from their minds an awareness of the true God whose existence and character are obvious in his creation and as a result of this, God has abandoned many among them to sexual desires and practices that provide evidence of human sinfulness and thus, the human need for God’s grace.

In turn, St. Paul’s words to the church at Corinth indicate that the apostle sees this kind of behavior as not simply unnatural, but as prohibitive for any who would enter the kingdom of heaven – along side idolaters, adulterers, thieves, slanderers, and drunkards (1 Corinthians 6:9,10).

What is Paul’s main point? It is that those who continue in behaviors such as these, and who do not repent, or exhibit sorrow, or even strive to refocus their lives and actions, may indeed love Jesus but they have not yet yielded to the absolute Lordship of Christ.

More importantly, the attempt to dismiss this Pauline understanding by redefining the Greek words used in this passage, as well as in 1 Timothy 1.8-10, is ultimately not only an example of creative interpretation, it is also a denial of the very real principle of the power of God to transform lives, no matter what dimensions their particular sins or failings may assume. For the word of grace that follows this pivotal passage is a striking one indeed, and perhaps one of the greatest illustrations in the Bible of the ability of God to change tenses in our lives. Take notice of the move from the ways things were to how God would have them be: “And that is what some of you were. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and by the Spirit of God” (1 Corinthians 6.11).

That is good news indeed to any and to all sinners – each of us – no matter what particular behavior or activity that may have otherwise entrapped us. For the promise of God is to make us new creations in Christ, no matter what our old and carnal selves may have been.

An honest examination of the scriptural witness regarding homosexuality suggests that, taken at face value, same sex intimacy violates God’s ultimate will for his children, in whatever circumstances or century they may find themselves. Likewise, the argument that homosexual behavior was of a different nature and character in biblical times than it is understood now is not supported by any careful reading of historical non-biblical texts or our knowledge of the ancient practices of those times.

The theological and linguistic loop-de-loops which some would employ to twist the meaning of the terms may be creative, but they fail to meet academic muster when divorced from their preconceived agendas, elevating personal experiences and preferences over those that are prescribed in the biblical witness itself.

This is why I disagree that the practices condemned in scripture are not the same as modern monogamous homosexual relationships, and thus the prohibitions against those practices are not applicable in the current situation of many. For though as a pastor I might wish that were not the case, I find that I have neither the luxury nor the liberty to proceed as if it were.

C. Chappell Temple is the lead pastor of Christ United Methodist Church in Sugar Land, Texas, a southwestern suburb of Houston. He holds degrees from Southern Methodist University, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and Rice University, and has served as an adjunct professor.

This article is excerpted from a dialogue he had with a ministerial colleague in the Texas Annual Conference regarding the issues of marriage and sexuality. The exchange can be found at Christchurchsl.org under the Media tab. It is reprinted by permission of Dr. Temple.

by Steve | Nov 22, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2019

A segment of the Leviticus chart from The Bible Project video teaching series (TheBibleProject.com).

By David Kalas –

My wife, Karen, grew up in a family full of milk drinkers. Everyone’s glass of milk was filled and refilled each dinner hour. As a result, milk never had a chance to go bad in her house.

In my house, on the other hand, we were not such big milk drinkers. A gallon of milk was more likely to have a long life in our refrigerator. We were careful, therefore, about checking the expiration date.

One day, when Karen and I were young and just dating, she was at our house as I was preparing a bowl of cereal. After I poured the milk, I was suspicious that it had soured, and so I asked her to taste it for me to see if it seemed fine to her. Coming from the home she did, she was completely naive about what she was about to put in her mouth.

So it is that we human beings want to have nothing to do with something that is expired. Once a thing is expired, you see – milk, a credit card, or a parking meter – it is of no use or value to us. The question for us is whether the Old Testament Law is expired.

Did the Law Expire with Jesus? The common reasoning I have heard from church folks is that the Law has nothing to do with us because it is “Old Testament” and we are “New Testament.” The idea is that the Old Testament Law has been rendered irrelevant because of Christ.

The great irony of that position is that it runs so contrary to what Christ himself said. It was Jesus – not Moses in the Old Testament or some Pharisee in the New – who said, “Until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass away from the Law, until all is accomplished” (Matthew 5:18 NASB). It was Jesus who said, “Anyone who breaks one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:19).

As we continue to read, we discover more fully Jesus’ attitude toward the Law. He cites, for example, the commandment not to kill. Most of us don’t come any nearer to breaking that commandment than we do becoming Knights of the Round Table. But Jesus presses the matter. He talks about being angry with another person, putting that common experience in the same conversation with killing.

Likewise, Jesus cites the commandment not to commit adultery. That is a sin some avoid out of genuine love and faithfulness, others out of purity and godliness, and others simply out of fear. But Jesus raises the stakes. “I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Matthew 5:28 NRSV). Suddenly the number of adulterers increases exponentially.

Rather than dismissing the Law or defusing it, Jesus intensifies and personalizes it. For as long as it is a set of behavioral boundaries I must not cross, I can probably stay out of foul territory. But Jesus teaches that it isn’t only my behavior, it’s my heart.

As I reflect on his teachings, I cannot conclude that the Law expired with Jesus. On the contrary, I am led to believe that the Law was the 101-level course, and now he is pushing me further and deeper. The things we learned in that elementary material are not discarded by Jesus but built upon by him.

Did Jesus Wave Off the Law? One day, a man tested Jesus asking, “Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law?” Jesus famously cited two commandments. From Deuteronomy, he quoted the command to love God; and from Leviticus, he quoted the commandment to love neighbor. Then he concluded, “On these two commandments depend the whole Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 22:40 NASB).

That summary statement has tempted folks to think the Law was nullified by Jesus’ simplification of it. “You don’t have to bother with those chapters of details,” we conclude, “so long as you love God and neighbor.” Thus the bulk of the Law is waved off.

The Golden Rule elicits a similar reaction. “So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you,” Jesus said, “for this sums up the Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 7:12). Because one rule sums up the rest, we are tempted to think it replaces the rest.

Imagine a basketball coach saying to the players, “Score more points than the other guys.” Such an instruction sums up all of the coaching, the designed plays, the offensive and defensive strategies, and such. But to sum them up is not to disregard them. On the contrary, as soon as I understand that the purpose is to score more points, I should ask, “How best can we do that?” Then the coach will remind me of all of the things we covered in practice.

Jesus keeps before our eyes the real purpose of the Law. Lest we get lost in a roundabout of fussy religiosity, he keeps us pointed in the right direction. It’s about loving God and neighbor. But once I am reminded of the real point, I will earnestly ask, “What does that look like to love God? How do I go about loving my neighbor?” Then I may turn to the Law for instruction. The teachings of Jesus do not dismiss the Law, but invite us back into it.

Did Jesus Fulfill the Law? “Do not think,” Jesus said, “that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets.” Yet that is precisely what many Christians do think. It is because of Jesus, they reckon, that we may ignore the Law. But he explains that his achievement with respect to the Law is a different one. “I have not come to abolish, but to fulfill” (Matthew 5:17). Our task, then, should not be to look for the expiration date, but for the fulfillment date.

Fulfillment is a great refrain throughout the Gospels. Fourteen times, Jesus or one of the evangelists refers to some Scripture being fulfilled. Likewise, the New Testament letter to the Hebrews sees in Jesus the fulfillment of so much of the Law.

Jesus is our great High Priest and our Paschal Lamb. He is the offering without blemish and the once-for-all atoning sacrifice. He is the serpent hung on a pole and the scapegoat that carries off the sins of the people. He goes behind the veil into the Holy of Holies, and it is his blood that is sprinkled as cleansing, as sanctification, and as the blood of the new covenant.

Jesus does not abolish the Law of God, but fulfills it. He fulfills its types and figures. And he fulfills its righteous demands.

Now someone says, “Isn’t this just a matter of semantics, a distinction without a difference? What does it matter whether we say the Law is ‘expired’ or ‘fulfilled’? Either way, we don’t have to worry about it anymore.”

I disagree. A thing that is expired is a thing that has become no longer good. But a thing that is fulfilled has become more good. The Law has not become irrelevant for us because of Christ; it has become better for us because of Christ!

The Case of the Credit Card. Let’s say I have a credit card on which the embossed expiration date is three years from this month. Imagine that I take that card to make a purchase today, but the clerk returns it to me and says, “I’m sorry, I can’t accept this card because it’s expired.”

I’m surprised and puzzled as I take the card back. After looking at it again, I reply, “No, no, it doesn’t expire for three more years!” I direct her attention to the date on the card.

“Yes, I know that’s what the card says,” she responds, “but I say that it is expired now.”

That would be ridiculous, of course. It is not the prerogative of a cashier to tell me that my credit card has expired. The expiration date can only be set by the bank that issued the card.

And so it is with the Old Testament Law – and with the larger whole of Scripture, as well. The only One who is eligible to say that any part of the Law (or the Bible) is expired is the One who issued it.

In mainline American Christianity, however, we commonly take that prerogative for ourselves. It would be amusing if it weren’t so serious. And our guiding principle is equally amusing, and fairly transparent. Simply: we tend to edit out of Scripture the parts we don’t like.

I suppose it was alright, when I was a boy, for my mother to cut the crust off of my bread because I didn’t like that part. It is not alright, however, for me as an adult to cut off parts of the Bible because I don’t like them. From the New Testament on, Christians have understood that certain parts of the Law have been fulfilled. The rituals, the symbols, and the blood all point us to Christ. Since Christ has come, we no longer need to settle for his antecedents, but we may rejoice in them and be edified by them in the same way we are by the symbols that may adorn our sanctuaries.

Likewise, we know that God has established a new covenant with a new people. Some of the signs and practices that were meant to identify the Old Testament people of God are no longer applied to the New Testament people of God. We have other signs and practices that identify us. And therein lies the key to better understanding our relationship to the Old Testament Law. Some particulars change from Old to New, from Israel to the Church, from Law to Gospel. Some particulars change, but the principles remain.

We do well to remember the Psalmist’s view. The longest chapter in the Bible, Psalm 119, praises and thanks God for the Law. If we were told that the longest chapter in the Bible was an expression of gratitude to God for something, what thing would we guess? We might make a long list before coming to the Law.

The Psalmist understood that those who live according to the Law are happy, that his instructions are a source of pleasure and wisdom, and that the teachings of the Law give freedom. The Psalmist says that the Law is worth more than earthly treasures, that it is perfect, and that it is eternal.

It is not milk, you see. It does not go bad.

David Kalas is the senior pastor of First United Methodist Church of Green Bay, Wisconsin. This article is adapted from The Gospel According to Leviticus: Finding God’s Love in God’s Law (Abingdon). It is reprinted by permission.

by Steve | Nov 22, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, Nov-Dec 2019

By Nako Kellum –

Rural cooking pot repaired with kintsugi technique.

My father is a potter. He lives in Japan. After his retirement, he began to study pottery, and since then, he has produced hundreds of cups, bowls, and vases. He has given me a chalice set for Holy Communion, and several mugs, cups, and rice bowls. I felt bad when I had to tell him that I (actually it was our cat) broke a cup that he had made for me. I did not want to discard it, because I cherished the fact that he made it for me. Surprisingly, his answer was, “No problem! I can just do tsugi.”

In Japanese, tsugi (tsoo-gee) means “to mend,” and we use this word when we mend pottery, china, or lacquered items. We use glue or lacquer to put the broken pieces together, and if the pottery or china is very special, the artisan will perform a “kin-tsugi” repair. Kintsugi (keen-tsoo-gee) is a step beyond a lacquer repair, in that the artisan inlays gold powder over the repair as well. This began in the 14th century, when the practice of tea ceremony became popular in Japan. People who practiced the art of tea ceremony did not want to discard expensive tea bowls when they broke, so they came up with the idea of “kintsugi,” i.e., mending the broken pieces with gold.

When you repair a vessel using kintsugi, you will see gold lines and fillings where there were cracks and chips. You can tell the pottery was broken, but it looks beautiful in a new and different way. Kintsugi makes the broken vessel beautiful again, and it makes the pottery stronger, because of the lacquer.

Kintsugi is a good analogy of how God works in us. We are broken, but he “mends” us.

Occasionally, I hear stories from people who have gone through very challenging seasons in their lives. I am saddened and heartbroken when I hear what they go through, whether it is abuse, illness, loss, addiction, or broken relationships. What amazes me, however, is their resilience. Most of them confess that they are still around because of what God has done for them, or that they are stronger because of the trials. Some say that God used their past to help others. It is as if God mends the cracks and the chips, and makes something new and stronger.

When I was a young child, I did not like to break things, often crying when I broke something. The first time I broke my doll, I started crying, and my mother said to me, “Well, everything that has a shape breaks eventually.” She was telling me that anything made of matter would not last forever. She was never upset with us when we broke things accidentally, but repeated, again, “Everything that has a shape breaks eventually.” It was her way of comforting us, and at the same time, teaching us to let go of things.

Though she said that, I knew that she performed “tsugi” on some of her favorite china and pottery. It wasn’t kintsugi, as she just mended them with glue. Some pieces still sit in the china cabinet in my parents’ house. She did not discard them (as she did my doll), but she picked up the pieces and put them back together.

I feel comfort in the fact that God does not discard us because of our brokenness. Just as everything that has a shape breaks, we human beings are broken. All of us have cracks and chips that come from sin, weaknesses, and hurts. Our tendency is to hide that brokenness from each other and at times, even from God. The idea behind kintsugi is quite the opposite. Instead of hiding brokenness, kintsugi embraces brokenness and uses the imperfections to make something beautiful.

Interestingly, the Apostle Paul compares us with pottery, or jars of clay: “But we have this treasure in clay jars, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us” (1 Corinthians 5:7, NRSV). I wish we were compared to metal, which is difficult to break, but, we are clay jars. God’s power shows through our weakness, brokenness, and shortcomings, just like the gold lines in kintsugi. God is not ashamed of our cracks and chips. Instead, he uses them to show his power and glory, mending us from the inside out, with his very presence.

I asked my father if he would use kintsugi to mend my broken pottery. He looked into it, but the materials were too expensive. This is because kintsugi uses real gold and natural lacquer. From reading an interview with kintsugi artist Yuko Yamashita, natural lacquer is collected from a lacquer tree that must be at least ten years old. The lacquer needs to be collected between early summer and fall, and one can only extract about one cup of lacquer per tree. After the lacquer is collected, the tree is cut down for lumber. Yamashita says it is as if the lacquer tree gives up its life in order for broken pottery to have a new life. Gold and natural lacquer are precious materials in their own right. Kintsugi costs…a lot.

It cost God to mend us, as well. God mended our brokenness through his Son’s broken body. Recently, our church started a weekly Holy Communion service on Monday nights. Every time we celebrate Holy Communion, I am reminded of my own brokenness and how much I need my Savior and Lord, to mend me. It reminds me of Jesus, who gave his life, so we can have true life. God had the power to make Jesus’ broken body into a new resurrected body, and he has the power to make us new as well.

Kintsugi is not about restoring the pottery perfectly to its original condition. It is about making something new, using what was already there. The cup does not become a plate, but the cup that is mended with gold is not the same cup that was broken. The kintsugi part of pottery is called “keshiki”(kay-she-key) – “a landscape.” It is a new landscape that the owner of the pottery can enjoy.

How can we be “keshiki” – a new landscape – for God, and for others, to enjoy? We can start by offering ourselves to God. We do not need to hide our brokenness and imperfection from God, because he has the power to mend it. We cannot do it ourselves, but the Lord of the Resurrection can. There is nothing beautiful about brokenness. We are not “beautifully broken.” However, I would suggest that we can be “beautifully mended” in Jesus, when we let God work in us, for he is the Potter, just as we are the clay.

Do we trust our Heavenly Father as the Potter? Our church, the United Methodist Church, is broken. Some people may say its cracks and chips are beyond repair, but I believe God can mend us with gold – the “gold” being his presence, and his power. It does not mean he will bring us back to how we have been, or to our idea of “unity.” It will be something new when we let God mend us, instead of trying to fix it ourselves.

“Kintsugi” at times adds more value to the pottery than its original form. There are people who intentionally break their pottery and do “kintsugi,” so it will have more value. What if, by letting our Father, our Potter, mend us, it adds more value, as the church, to his Kingdom? What if we pray together, placing ourselves totally in God’s hands, and as the whole church we seek his will? I trust that God will mend us and give us a new “keshiki,” a new landscape, and I believe it will be beautiful.

Nako Kellum is co-pastor in charge at First United Methodist Church of Tarpon Springs in Tarpon Springs, Florida.

In six months, the General Conference of The United Methodist Church will meet once again. And once again the business of the conference will be consumed with our differences regarding sexual ethics.

In six months, the General Conference of The United Methodist Church will meet once again. And once again the business of the conference will be consumed with our differences regarding sexual ethics.