by Steve | Sep 3, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September-October 2019

What Does it Mean to be a Wesleyan Christian?

By David F. Watson –

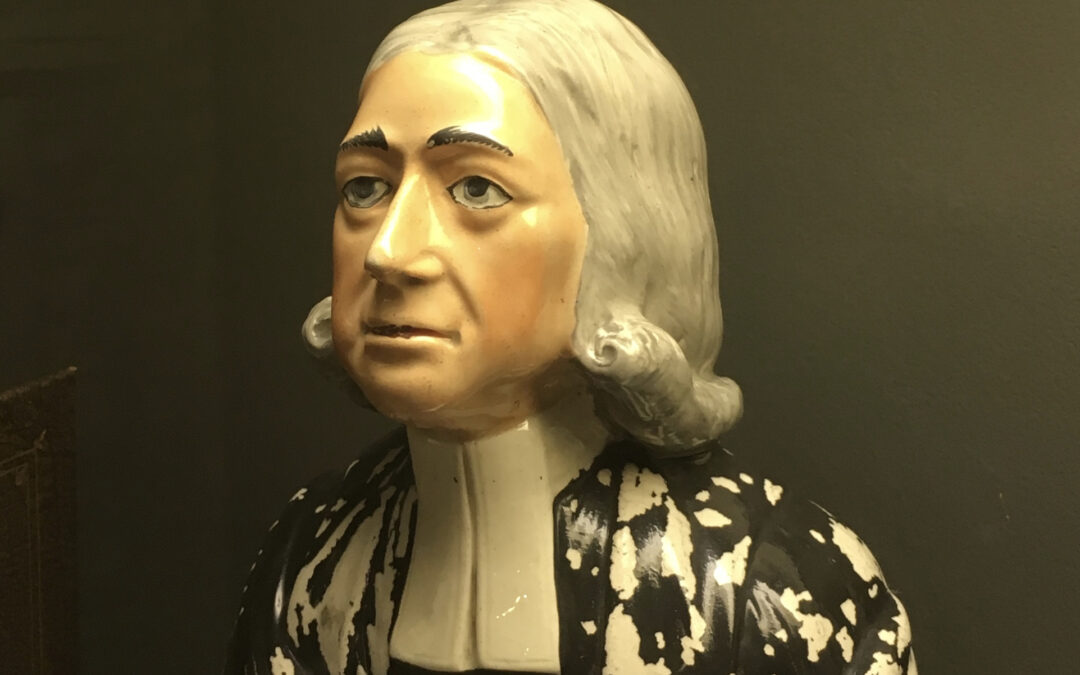

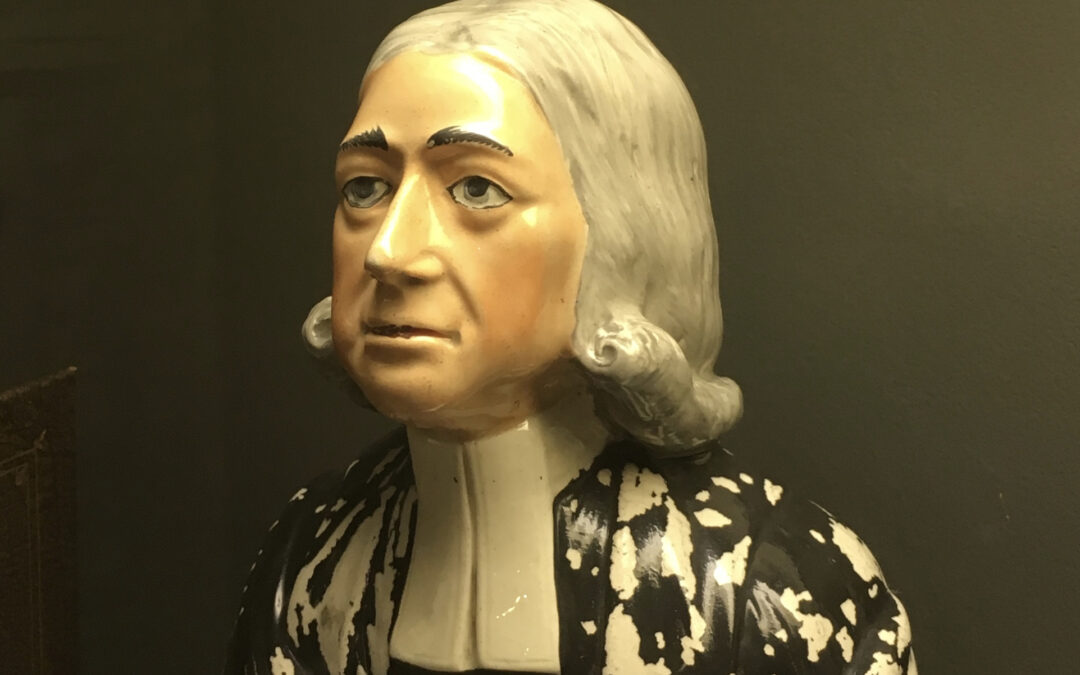

John Wesley (1703-1791) believed that God had raised up the people called Methodists to “reform the nation, particularly the church, and to spread scriptural holiness over the land” (“Minutes of Several Conversations”). The core of the Wesleyan/Methodist tradition is holiness.

What is holiness? It means different things to different groups of people. For Wesley, however, holiness was about transformation. We human beings, he believed, are broken, sinful creatures. Left to our own devices, we will not live in ways that honor God. In fact, we can’t honor God with our lives – at least not consistently – because we stand under the power of sin. The world is not as it should be. Human beings are not as we should be. Our minds, our hearts, our desires are disordered.

In his great mercy, God has given us a savior in Jesus Christ. When he died on the cross, Jesus made it possible for us to have peace with God and to escape the power of sin over our lives. We receive Christ into our hearts through the power of the Holy Spirit, and the Holy Spirit comes to us most readily as we seek him through practices such as reading Scripture, praying, and receiving communion. To be holy means that we are “set apart” from the world by the transforming power of God.

In many cases and places, our zeal for holiness has flagged. A renewed expression of Wesleyanism will require concerted work of retrieval. In other words, we need to recommit ourselves to some of the core beliefs and practices that characterized early Methodism. For Wesley and his followers, the Methodist movement involved a commitment to holiness lived out in several ways. Holiness was rooted in Scripture. It was lived out in community. It was facilitated by the means of grace, and it was expressed in solidarity with the poor.

Holiness was rooted in Scripture

In his Complete English Dictionary, Wesley defines a Methodist as “one that lives according to the method laid down in the Bible.” Wesley did recognize other sources of knowledge, even religious knowledge, but he believed Scripture to be God’s definitive revelation. Tradition, especially that embodied in the teachings of the Church of England, could help to illuminate the meaning of Scripture. Reason was simply necessary in order to make sense of Scripture at all.

Wesley believed that it was also important to have a personal experience of salvation. Such experiences confirmed Scripture’s primary message, that we are saved from sin and death by the work of God through Jesus Christ. These other resources were important, but Wesley believed Scripture to be definitive for Christian faith and life in ways that other sources of knowledge were not.

For Wesley, the whole content of the Bible, that great narrative of salvation from Genesis to Revelation, was about salvation. Today we have all but lost a sense of Scripture’s unity and coherence. There are many reasons for this. The emphasis in biblical scholarship on studying Scripture in bite-size parts (or pericopae), a loss of trust in divine revelation, and even postmodern skepticism toward the idea of “truth” itself have undermined the idea that the Bible is a single work with an overarching message.

As we look to the future of the Wesleyan movement, we would do well to recover a framework whereby we understand Scripture as a book about salvation. It begins with creation, takes us through the fall, and narrates the pendulum swings between human faithfulness and sinfulness. In Christ, God acts once and for all to deliver us from sin and death, and we anticipate the fullness of redemption when God will bring together a new heaven and a new earth. To read Scripture as a Wesleyan is to read it as a book about salvation meant to lead us into salvation.

Holiness was lived out in community

We United Methodists often hear talk of “holy conferencing” and “social holiness,” but in many cases Wesley would not have recognized our use of these terms. As he used them, both referred to Methodist “class” and “band” meetings – two distinct small group meetings in which Christians came together to build one another up in the faith and hold each other accountable for living in ways consistent with the will of God.

The people called Methodists were to “watch over one another in love.” In particular, people in classes were held accountable to the General Rules: do no harm, do good, and attend upon all the ordinances of God (discussed below). Members of classes were also required to give money toward relief of the poor if they were able.

Over time, both class and band meetings fell out of common use, replaced in large part by the Sunday school movement. Sunday school, however, has never had the same purpose as class and band meetings. At first its function was primarily educational. In many cases it is now primarily social. The highly personal interactions of class and band meetings and their focus on holy living and accountability are largely missing from our churches today. To recover the power of early Methodism, we will have to recover the discipline of “social holiness”: a godly life formed in deep community with other believers.

Holiness was facilitated by the means of grace

Early Methodism involved an openness to the work of the Holy Spirit and a reliance on the supernatural power of God to replace our hearts of stone with hearts of flesh. Wesley believed in an active and living God, a God who loves us and wants to draw us closer to himself. He knew that God could work through anything and anyone, but that there were certain practices that God had specifically given us for growth in faith and holiness. This is why the third of the General Rules requires that we should attend upon “all the ordinances of God, which it spells out specifically as:

• The public worship of God

• The ministry of the Word, either read or expounded

• The Supper of the Lord

• Family and private prayer

• Searching the Scriptures

• Fasting or abstinence

In other words, Wesley believed that Methodists should attend to worship, Scripture, the Lord’s Supper, prayer, and self-denial. These practices are not just beneficial; they are commanded in Scripture. There are other practices, such as participating in class and band meetings, that aren’t commanded in Scripture, but are beneficial (“prudential”) nonetheless. Through each of these practices, we come to know and love God more fully.

Wesley was quite clear that these practices themselves do not save us. They do not and cannot make us righteous before God. Rather, through these practices we grow closer to God, who offers us grace by the power of the Holy Spirit. It is that grace that saves us, through our faith in Jesus Christ. Yet the more we partake of the means of grace, the more we will experience the fullness of salvation in the present.

Holiness was expressed in the world

Wesley was deeply concerned for the poor and vulnerable. As noted above, members of class meetings were expected to contribute money to the poor, excepting those who could not afford to do so. In his book The Radical Wesley and Patterns for Church Renewal (Wipf and Stock, 1996), Dr. Howard Snyder writes, “From the beginning [Methodism] was a movement largely for and among the poor, those whom ‘gentlemen’ and ‘ladies’ looked on simply as part of the machinery of the new industrial system. The Wesleys preached, the crowds responded and Methodism as a mass movement was born” (33).

When Wesley converted the abandoned Royal Foundry in London to a Methodist meeting place, he included there a free school that could educate up to sixty children at a time, a shelter for widows, and a free dispensary (an office for the provision of medical supplies and services). In an age when it was commonplace for the wealthy to purchase a pew in the church, Wesley insisted that all seating in the Foundry’s chapel consist of common benches. There was no difference in seating for rich or poor (see Snyder, 48).

Wesley had housing on the second floor of the Foundry. “I myself,” he wrote, “as well as the other Preachers who are in town, diet with the poor, on the same food, and at the same table; and we rejoice herein, as a comfortable earnest of our eating bread together at our Father’s kingdom.”

By contrast with churches in many other parts of the world, many American churches are unbelievably wealthy. In parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, for example, churches scrape by on meager resources, and many Christians live in poverty or on its very edge. I have witnessed with great admiration and appreciation the work of churches in the U.S. to address poverty both domestically and abroad. But we can do more – much more. The resources are there. What is required is an awareness of poverty and the will to address it. To be a Wesleyan Christian today will mean a renewed focus on ministry with the poor, which will include the willingness to have less so that others may have enough.

To live as Wesleyan Christians today will involve a self-conscious process of recovery. It won’t be easy. Not everyone will like it. Then again, not everyone liked Wesley’s vision and methods in his own day, but he launched a movement that has changed countless lives across the globe. Wesley worried that the people called Methodists would someday become a “dead sect,” having the form of religion without the power.

In many places his warning has proved prophetic. Perhaps God will once again fill us with the power of those early days of the Methodist movement if we seek his face like those who went before us.

David F. Watson is the academic dean and professor of New Testament at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of Scripture and the Life of God: Why the Bible Matters Today More than Ever (Seedbed).

Art: A Staffordshire bust of John Wesley at the World Methodist Museum at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina. Photo: Steve Beard.

by Steve | Sep 3, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September-October 2019

Christ Washing the Feet of the Apostles by Meister des Hausbuches, 1475

By Philip Yancy –

It began with a gathering at Denver’s snazzy Convention Center. I had agreed to host a forum with sixty business leaders before the Colorado Prayer Luncheon, but as a freelancer with precious little business experience, I had to search for something worth discussing. Fortunately, I had just read the new book by New York Times columnist David Brooks, The Second Mountain.

Brooks describes the journey on which successful people embark: enrolling in prestigious schools, climbing the corporate ladder, accumulating tokens of wealth and success. Then one day, some of these achievers wake up with a hollow feeling, wondering, “Is that all there is?” Others are gobsmacked by some event – the death of a loved one, a fractured marriage, bankruptcy – and find themselves in free fall. Now what?

I had listened to Brooks describe his own fall in an interview on Good Morning America. As a famous columnist and best-selling author, he reached an enviable summit. Yet when his 27-year marriage ended in divorce and depression set in, he realized he needed to climb another mountain, one that offered community and meaning. A friend told him, “I’ve never seen a program turn around lives. Only relationships turn around lives.” Hearing about a family who welcomed neighbors for a weekly dinner, Brooks showed up in his business suit one evening and rang the doorbell.

One of the neighbor kids opened the door, and Brooks stiffly extended his hand for a formal handshake. The kid looked him over, said, “We don’t do that here. We hug here,” and gave him a bear hug. Inside, Brooks found a household led by a warm, loving couple who hosted an average of 26 visitors from the neighborhood for dinner. For five years Brooks joined them on most Thursday evenings, and in time that diverse, lively community helped heal the loneliness in his soul.

To the business leaders, I read aloud Brooks’ conclusion: “The natural impulse in life is to move upward, to grow in wealth, power, success, standing. And yet all around the world you see people going downward. We don’t often use the word ‘humbling’ as a verb, but we should. All around the world there are people out there humbling for God. They are making themselves servants. They are on their knees, washing the feet of the needy, so to speak, putting themselves in situations where they are not the center; the invisible and the marginalized are at the center. They are offering forgiveness when it makes no sense, practicing a radical kindness that takes your breath away.”

David Brooks began exploring a second mountain, one in which ascent begins with apparent descent.

After the meeting with business leaders, we all moved to a huge ballroom. More than a thousand guests had assembled for the annual prayer luncheon, where Christian groups and individuals are encouraged to invite their nonreligious friends. As the speaker, I sat at the head table with the governor and mayor and several dignitaries from the city council. The elite of Denver, many of whom were busily checking their cell phones for last-minute messages, filled 140 tables around us.

The tone was somber for, just two days before, a suburban school had experienced a fatal shooting, a few weeks after the twentieth anniversary of the Columbine tragedy. The mayor, an African-American man who rose from homelessness to head a major city, practically preached a sermon, quoting Isaiah and urging us to care for the poor and the suffering. Meanwhile the governor, the first openly gay and the first Jewish person to hold that office, probably wondered who had scheduled him for an event among so many Christians. He responded with thoughtful remarks about the power of prayer in times of crisis. I tried to address both audiences: the Christian core, and their skeptical friends and colleagues who may have attended out of curiosity or civic obligation.

Three hours later I entered a federal prison. I had agreed to speak there as well, to honor ten men who had completed a rigorous four-year seminary program. The contrast in settings could not have been starker. Whereas the prayer luncheon was a fancy, dress-up affair, the prisoners all wore drab uniforms, with their names and numbers stenciled on the front. They lived behind bars and razor wire, ate institutional food each day, and were defined by their failures, not their successes. In David Brooks’ image, they had fallen off the first mountain, spectacularly.

I learned details of some of the graduates’ lives. One inmate started reading the Bible while in solitary confinement, and spent the next four years in the seminary course while also translating a German novel by Gerhart Haupmann called The Fool in Christ. Another had earned degrees in Biblical Studies and Theology and was working on a Masters in Divinity. Another said, “It was not until I came to prison that the Lord found me. I was the one that was lost and could not see. I was not only found but was able to see just how much the Lord loves me.”

One of the graduates wiped away tears as the recorded strains of “Pomp and Circumstances” filled the room. He later told me that his mother, who traveled from Nebraska to visit him every chance she got, had died that week. She would be buried back in Nebraska on Mother’s Day, and officials had denied his request to attend the funeral.

Although we were celebrating graduation from the seminary program, mostly the men spoke of another “graduation,” the day in 2021 or 2024 or whenever they would be released to resume life outside the prison walls. One inmate admitted addiction to some form of drug or alcohol from the age of nine. He had five drug-related felonies on his record, and was serving a 15-year sentence for distribution of meth resulting in a person’s death. He was using the time in prison to lose weight (75 pounds so far!) and hoped someday to work with kids in Teen Challenge, guiding them away from the path he had taken.

Another confessed that, after no more than seven years in school, he was barely literate and never read books. In prison he was working on his education and trying to “grow as a child of God.” He hoped in the future – “when I get out, God willing” – to return to prison as a teacher, training others. The seminary program, he said, “has helped me so much I must tell everyone about it.”

At the Colorado Prayer Luncheon we had enjoyed a full meal at tables set with cloth napkins and china. The prison served slices of carrot cake on paper plates with plastic forks. Though delicious, the cake had an unusual flavor of spices I couldn’t identify (“We have to improvise in this kitchen,” the chef admitted with a grin).

I left the prayer luncheon with a stack of business cards. I left the prison with empty pockets – we had to lock all belongings in our cars before entering – yet inspired by the stories of redemption I had heard. A late-spring snow was falling as the electric gate clanged shut and I walked out with a group of volunteers who have been coming for years, without pay or fanfare, to bring hope and renewal to the inmates locked inside.

The prisoners, volunteers and, yes, David Brooks have all learned the same lesson, that to climb the second mountain, ascent begins with apparent descent.

Philip Yancey is the author of innumerable books, including best-sellers such as Disappointment with God, Where is God When it Hurts?, The Jesus I Never Knew, What’s So Amazing About Grace? and Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference? This article first appeared on his website (philipyancey.com) and is reprinted here by permission.

by Steve | Sep 3, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September-October 2019

Bishop Kenneth H. Carter gives the sermon during opening worship for the 2019 United Methodist General Conference in St. Louis. UMNS file photo by Kathleen Barry.

By Kathy L. Gilbert (UMNS) –

Several United Methodist annual conferences meeting this summer looked at plans for a new Methodism centered around how to divide The United Methodist Church.

More than 20 of the regional gatherings rejected the Traditional Plan approved by the 2019 General Conference and voted to remove the phrase “homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching” from the denomination’s lawbook. The United Methodist Church has 54 U.S. regional conferences that meet in May and June.

Other conferences had passionate discussions about the future of The United Methodist Church but stood by the action of the 2019 General Conference.

The Book of Discipline, the United Methodist policy book, says that the practice of homosexuality “is incompatible with Christian teaching,” and bars “self-avowed practicing homosexuals” from ordination. Despite passage of legislation during General Conference 2019 that retains church bans on ordaining gay clergy or same-sex marriages and strengthened enforcement measures for violating those bans, resistance has been strong.

The Greater New Jersey Conference has a 35-member team working on a way “to help congregations thrive in different expressions of an emerging era of Methodism.”

Action steps by the Greater New Jersey Way Forward Team include launching 75 congregations in one of three pilot programs:

• Congregations that hold a scriptural view that same-gender weddings should not be performed in churches and that LGBTQ persons should not be ordained.

• Congregations that hold different scriptural views about LGBTQ people and can be together recognizing there will be different practices and understanding of the LGBTQ community.

• Congregations that hold a scriptural view that Jesus invites everyone to participate fully in the church and that all churches should allow same-gender weddings and be open to appointment of an LGBTQ clergyperson.

Eastern Pennsylvania declared by a narrow margin to be a One Church Plan Conference “in spirit.” During the heated debate, Bishop Peggy Johnson was challenged for letting the resolution proceed despite its disagreement with church law. She called the measure “aspirational” and thus admissible according to a recent United Methodist Church Judicial Council ruling. Conference members voted to appeal her decision to the Judicial Council.

The North Carolina conference approved a task force to study pastoral care for LGBTQ people. The Rev. Laurie Hays Coffman proposed the task force citing rising gay teen suicide rates, increasing murder rate for transgender people and many requests from clergy and lay people asking for guidance on how to care for LGBTQ people. The task force will meet over the next year and report back to the 2020 North Carolina Conference.

The Michigan Conference supported the creation of a central conference in North America. Pacific Northwest also called for the formation of the United States as a central conference. Central conferences, the regional church bodies in Africa, Europe and the Philippines, can adapt parts of the Book of Discipline, the church’s lawbook, for their specific missional context.

Minnesota delegates voted to adopt a vision that commits to the full inclusion of LGBTQ people.

Mountain Sky, Desert Southwest, Upper New York all formed teams to explore options to move forward. Western Pennsylvania called for the Connectional Table to create a task force to prepare a process for dividing the denomination. New England approved commissioning the Open Spirit Task Force to examine how United Methodists might create a new church body.

California-Nevada recommended creation of a structural change task force.

Alaska, Great Plains, Central Texas, and Western North Carolina affirmed the four commitments that came from the UMC Next meeting held at United Methodist Church of the Resurrection May 20-22. These include:

• To be passionate followers of Jesus Christ, committed to a Wesleyan vision of Christianity.

• To resist evil, injustice, and oppression in all forms and toward all people and build a church that affirms the full participation of all ages, nations, races, classes, cultures, gender identities, sexual orientations, and abilities.

• To reject the Traditional Plan approved at General Conference 2019 as inconsistent with the gospel of Jesus Christ and resist its implementation.

• To work to eliminate discriminatory language and the restrictions and penalties in the Book of Discipline regarding LGBTQ individuals.

One resolution came before the Missouri Conference to provide $30,000 from which congregations can submit grant applications to assist ministries for the LGBTQ community or to lift up persons from that community into missional leadership. According to the Book of Discipline, the church is still called to be in ministry to the LGBTQ community. Funds from the Missouri resolution would go toward fulfilling that mandate.

Alaska, one of the denomination’s missionary conferences, discussed the next expression of Alaska Methodism. Two alternatives were presented – become a mission district of another conference or withdraw from the denomination.

Four of the seven conferences in the Western Jurisdiction – Oregon-Idaho, California-Pacific, Desert Southwest, and California-Nevada – voted to petition the jurisdiction’s College of Bishops to convene a special conference to consider separating from the denomination.

Meeting after the close of the California-Nevada conference, Bishop Minerva Carcaño and her cabinet met and released a statement that said, in part, that disaffiliation “would not fulfill the promise of the Wesleyan spirit and Methodist ethos, or the calling to leadership as a jurisdiction.”

LGBTQ people were commissioned, ordained, or licensed in the California-Nevada, Baltimore-Washington, Michigan, New York, Northern Illinois, Oregon-Idaho, Desert Southwest, Mountain Sky, and North Texas conferences. North Texas Bishop Michael McKee said the openly gay pastor ordained in his conference is single and does not violate the Book of Discipline.

Conferences that rejected the Traditional Plan included: Oregon-Idaho, Pacific Northwest, Northern Illinois, Great Plains, California-Pacific, Desert Southwest, Upper New York, Minnesota, California-Nevada, Iowa, Wisconsin, and North Carolina.

Conferences calling for removal of incompatibility language from the Book of Discipline: Virginia, Indiana, North Carolina, California-Pacific, New York, Dakotas, Upper New York, and California-Nevada.

Among the conferences that stood by the action of the 2019 General Conference was Holston. The Holston Conference approved a ‘commitment’ resolution that fell short of disagreeing with the Traditional Plan. It resolved to “join hands as one, united through our prayers, our gifts, our service, and our witness as we work together toward God’s hope for the people of Holston and grieve for the harm caused to the body of Christ and its witness in the world.”

Indiana left in the language “homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching” but added language calling for strict global enforcement of laws prohibiting the sexual exploitation of children and for adequate protection, guidance, and counseling for abused children. Another amendment to the petition added, “The Church should support the family in providing age-appropriate education regarding sexuality to children, youth, and adults.”

A petition to remove the current qualifications for ordination failed to pass the Indiana Conference.

In East Ohio, two resolutions to realign the church to allow both traditional and progressive understandings of LGBTQ clergy and same-gender weddings and to adopt the four tenets developed by UMC Next were defeated.

The Kentucky Conference concluded with an “emotional and sometimes painful” debate over whether to remove the incompatibility language, said Alan Wild, ministry assistant to the director of new church development for the conference. The effort was voted down 458-283.

The Rev. George Strunk, one of the sponsors of the resolution, struggled with composure during the debate, his voice breaking at times. “Being Methodist has never felt so difficult as it does today,” Strunk said.

The Rev. Bill Arnold, one of those who spoke against the measures, said that approving the petition would be “a major break with Christian tradition.” The church must not become a window into the larger culture, he said.

At one point, Bishop Leonard Fairley admonished the delegates not to clap. “No applause. We are going to do this in the spirit of Christ. This is not about winners and losers.”.

Kathy Gilbert is a news writer for United Methodist News Service.

by Steve | Sep 3, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September-October 2019

Hemedi Ndjadi, age 17, has been part of the Kindu United Methodist Orphanage in East Congo for three years where he is learning carpentry skills to become a workshop manager. Photo by Chadrack Tambwe Londe, UM News.

By Chadrack Tambwe Londe (UMNS) –

KINDU, Congo – The United Methodist Church in East Congo continues to have a heart for orphans in the region. Since 2012, the church has been taking orphaned children under its wing at Kindu United Methodist Orphanage, which has more than 100 orphans in its care.

“In the beginning, the orphanage started with 22 children, but today, we are supervising 104, of whom 98 are staying with host families,” said Furaha Tshoso, head of the orphanage. The church tries to place children with foster families as quickly as possible. “When they are in foster care, children can sometimes forget that they are orphans, because they can stay and play with other children,” Tshoso said. The orphans range in age from 5 to 25. The younger children attend school, while the older ones learn job skills such as sewing, baking, soap making, and carpentry. Young women learn trades at the Mama Lynn Center, a United Methodist sanctuary for sexual violence survivors in Kindu, and the young men learn carpentry skills at local workshops.

Philomène Nyande, who supervises the children at the orphanage, said that teaching them trades is a way for the church to prepare them for adult life and financial independence. “Thanks to the apprenticeship of the few trades, adult orphaned children managed to become financially independent and provide for their (younger) brothers and sisters,” she said.

Tshoso said the orphanage doesn’t have the money to buy the newly trained young people their own tools at the end of the training, but they are able to earn money through the skills they’ve learned. The hope is that they can save enough to open their own workshops, she said.

The church also offers health care and psychological support to the children. “Some young children do not understand the death of their parents. They have trouble digesting this, hence the need to provide psychological support. We talk to them about what happened. We encourage them to pursue life by studying,” Tshoso said. She said the East Congo Episcopal Area cares for the children through local means and financial support from the United Methodist Board of Global Ministries and the Tennessee and Memphis annual conferences.

“Under the leadership of Bishop Gabriel Yemba Unda, we mentor these children to enable them to have a bright future. That’s why the church provides their schooling and supports their needs,” Tshoso said.

Members of First United Methodist Church in Martin, Tennessee, have been helping to provide scholarships for the orphans since 2014. The Memphis Conference church has a partnership with the East Congo Episcopal Area.

“Our church has been in relation with East Congo for several years,” said the Rev. Randy Cooper, pastor at First United Methodist Church. “We have donated money for scholarships for schoolchildren for over five years. I am sure we have provided more than 100 scholarships … People need to know that $50 can send a child to school for a year.” He said his church also has provided money to build eight churches in the East Congo Episcopal Area, and this summer, members are raising money to build two more.

The scholarship money helps send the orphaned children to United Methodist schools, rather than public schools. The foster families also often contribute to the school fees, when the scholarships aren’t enough, said the Rev. Paul Ketoka Lokondo, treasurer of the East Congo Episcopal Area.

Nyande said that apart from schooling and psychological care for the orphans, the home also organizes entertainment and fellowship activities. “We organize banquets to allow the children to have fun and show them that they have a family in Christ despite what has happened to them. We share meals together to show them our brotherly love,” Nyande said.

Enoka Ndjadi Lubwende, 21, is one of the orphans supported by the United Methodist Orphanage. “I have been an orphan of father since 2006. I suffered a lot after the death of my father and I had to give up my studies and resume with a lot of difficulties. My father’s family had to take everything we had.”

When Lubwende was in his third year of high school, he was placed in foster care after his mother remarried and her new husband rejected the teenager. The orphanage helped him continue his studies and he’s currently in his third year at the Higher Institute of Education in Kindu studying geography and environmental management. “We will have a lot of work to do for orphaned children,” Lubwende said. “As God has given us the grace to be cared for, we also plan to give other orphans a chance.”

His story is similar to that of the dozens of other children in the United Methodist orphanage. Hemedi Ndjadi, 17, has been a part of the center for three years. “My father died in an accident when I was 12 years old. I stayed with my mother who died two years later. I live with a member of the church who has agreed to host me. I did not succeed at school, (so) I preferred to come and learn carpentry to prepare me in life,” he said.

The orphanage reached an agreement with a local woodworking shop where he is being taught how to manufacture lounge chairs. He hopes one day to open his own workshop.

Ali Mbaruku, who is teaching Ndjadi, said he has become a good carpenter. “Hemedi is learning fast. I am sure he will be a great workshop manager,” Mbaruku said. “The Methodists have already brought me two other young people like him. Hemedi teaches them quickly. He already knows how to make chairs and is still learning about upholstery.”

The Rev. Celestin Lohalo and his wife have been raising another orphan, 9-year-old Henriette, as their own daughter. “My daughter does not know that we are not her biological parents. We consider her our own daughter. One day maybe, we will tell her the truth about her parents, but for the moment, we do not want to disturb it,” he said.

“Orphans are in the category of people whom God defends. Widows are part of it, too. It is in the Book of Deuteronomy. The Lord God recommends us to give even tithing to this category of person. If you do that, God will repay you to the cent,” he said.

Chadrack Tambwe Londe is a communicator for the East Congo Conference. Donations to Kindu United Methodist Orphanage can be made through Advance #15138N.

by Steve | Sep 3, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September-October 2019

Blaise Pascal studying the cycloid. Sculpture by Augustin Pajou. Louvre Museum. Creative Commons.

By Michael DeVito –

What would be the criteria for someone to be considered amongst the greatest intellectuals of all time? In the same league as Einstein, Newton, and Aristotle? Would inventing the first calculator or designing Europe’s first transportation system be enough? How about inventing the mathematical study of probability theory and decision theory? What if someone were to do all of those things and pen some of the greatest French literature ever written?

Clearly any one of these accomplishments would qualify them as one of the greats. Yet, the 17th century mathematician, philosopher, apologist, and theologian Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) is often left off the list of history’s greatest thinkers.

That has been an epic oversight.

Born in France, Pascal had anything but a conventional upbringing. With the death of his mother only a few years after his birth, Pascal’s father (Etienne) was forced to quit his lucrative job as a lawyer in order to take on his new role as sole caretaker of his family. While it’s almost certain that young Blaise would have benefited greatly from his mother’s influence, the shift in his father’s focus from his vocation to caring for his son (specifically, Pascal’s education) provided the care and nourishment needed for the seeds of genius to blossom and thrive.

Etienne’s approach to homeschooling Blaise was considered, both then and now, to be truly unique, focusing on creative, hands-on problem solving, as opposed to a traditional approach which focused more on lectures and reading. Etienne also challenged Blaise by setting the level of difficulty of his studies a notch or two above what was required for someone his age.

Being himself a trained mathematician, Etienne would regularly hold discussion groups with world class scholars (including Rene Descartes and Pierre de Fermat), who would present cutting edge ideas to the group and, in turn, receive feedback and critique. Blaise was included by his father in these discussions early on in his life and would present his first mathematics essay on conic sections to the group at age 16. It was the combination of these factors that fostered and accelerated Blaise’s intellectual growth.

Pascal’s resume is in a league of its own and would require its own book to analyze sufficiently. In order to help his father, who had been reassigned to the position of tax collector (an occupation that was extremely time consuming at this point in history), Pascal designed the first mechanical calculator. Also known as the arithmetic machine, it dramatically sped up the process.

Pascal’s innovative scientific mind also challenged and upended conventional thought in physics and probability theory. “You cannot walk ten feet in the twenty-first century without running into something that Pascal’s thirty-nine years of the seventeenth century did not affect in one way or another,” writes James A. Connor, author of Pascal’s Wager: The Man Who Played Dice With God (HarperCollins).

Night of Fire. Pascal’s upbringing, along with being highly academic, was also one of strict religious commitment. He lived a life mostly characterized by piety and devotion to God. Yet like many of those brought up in a religious household, Pascal experienced a time of “worldliness” in his late twenties, which lasted for a couple of years. Historians believe that this period in Pascal’s life was prompted by the death of his father, as well as by being apart from his two sisters (despite strong opposition from her brother, his sister Jacqueline became a nun). Somewhat depressed, Pascal indulged in a number of activities that were not consistent with his religious upbringing.

Everything changed for Pascal on the night of November 23, 1654. Not much is known as to exactly what happened due to the fact that Pascal never told anyone about the event, but what can be said is that he had a profound religious experience that not only brought an end to the worldly indulgences, but drastically changed the trajectory of his life. Historians have referred to this experience as “The Night of Fire” because of Pascal’s only written reference of the event, a piece of parchment was found sown to the inside of his coat pocket after his death:

“From about half-past ten in the evening until about half-past midnight,

“FIRE.

“God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob not of the philosophers and of the learned. Certitude. Certitude. Feeling. Joy. Peace. God of Jesus Christ. My God and your God. Your GOD will be my God. Forgetfulness of the world and of everything, except God.”

Two aspects of this note shed light on the change in Pascal’s life and his work. First, the phrase “Forgetfulness of the world and of everything, except God” explains Pascal’s motivation to put an end to a lifestyle of worldly pleasure and refocus his attention towards God. Secondly, we see that Pascal praises the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and dismisses the god of the philosophers. Prior to this event, much of Pascal’s work had been in academia. However, after this experience, Pascal would leave most of his academic endeavors behind him and shift his focus specifically to the realms of theology and apologetics.

Heart and reason. Pascal’s theological writing reflected his understanding of the role of the heart, which he argued was foundational to humanity’s ability to reason and to assent to knowledge about God. Thus, much of Pascal’s theological and apologetic writing is focused on persuading the heart first, then the mind. It was this brand of theology that Pascal set out to defend after his recommitment to the Christian faith.

Pascal began working on a theological and apologetic treatise but unfortunately, due to the poor health that had afflicted him for the majority of his life, Pascal died before he was able to finish (at the age of 39). Pascal’s unfinished work was compiled and published two years after his death as a book titled The Pensées (or “Thoughts”), which is considered to be one of the finest works in all of French literature.

Original artwork by Sam Wedelich (www.samwedelich.com).

Pascal’s Wager. Pascal lays out a number of apologetic arguments for Christianity within The Pensées, but one of his primary arguments (one that is still engaged and utilized by philosophers and apologists today) is what has been called Pascal’s Wager.

The Wager is not an argument for the existence of God; rather, it is an argument that one is rationally compelled to believe in God regardless of whether or not he exists. Foundational to this argument is the mathematical reasoning known as decision theory, which one would utilize when trying to decide between competing courses of action where, ultimately, the outcome is uncertain. “God is, or God is not…. Reason cannot decide nothing here…. What will you wager?”

The illustration on page 30 portrays the basic idea of Pascal’s argument. Each box represents an outcome resulting from a given decision on the truth of a correlating state of affairs. The top left box represents the outcome if one were to wager that God exists and if God did in fact exist. Here one receives an infinite gain – namely, an eternity in heaven (not to mention a number of finite gains such as answered prayer).

The top right box represents one’s decision to wager that God exists and the possible outcomes if God did not actually exist. Traditionally the outcome assigned to this box has been a finite loss because one would have spent their time going to church, praying, tithing, etc., for seemingly no reason. (However, recent work in psychology and sociology has shown that those who believe in God tend to live happier, more fulfilled and, on average, longer lives. It is because of this that recent defenders of the Wager have argued that the outcome of the top right box should be seen as a finite gain.)

The bottom two boxes represent the possible outcomes if one were to wager that God does not exist. In the bottom left box, we see the outcome if one wagers that God does not exist and they are wrong. Pascal doesn’t mention hell as the outcome for this scenario in The Pensées. However, whatever the consequences are for wagering against God’s existence and being wrong, we can reasonably conclude, at a minimum, that this outcome is a substantial loss.

Lastly, the bottom right box shows the outcomes for wagering that God doesn’t exist and being correct. With the recent studies showing the benefits of belief in God, this box can arguably still be seen as a finite loss, even taking into account the fact that one wouldn’t waste time or resources on the church.

Based on this very basic analysis of the Wager, we can see that in all possible outcomes it is more rational to wager that God exists as opposed to not. Pascal summarizes this point: “Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is” (Pensées, 272).

Here the word “wager,” according to Pascal, does not mean that one can force themselves into believing that God exists, rather Pascal submits that one should live the Christian life (go to church, pray, fellowship, etc.) regardless of their unbelief in hopes that they will come to believe.

As one might expect, a number of objections have been raised to Pascal’s Wager over the past 400 years. Yet, in spite of these criticisms, the Wager continues to have a number of contemporary proponents within the philosophy of religion and is still a reliable argument in the apologist’s toolbox.

Pascal’s life and achievements were truly remarkable. In only 39 years of life, this 17th century Christian thinker radically advanced both academic and religious thought, and much of his work still has a major influence in today’s society. To my fellow believers and non-believers alike, I would strongly encourage you to spend some time studying the rich work of the great Blaise Pascal. What do you have to lose?

Michael DeVito received his MA in Philosophical Apologetics from Houston Baptist University and is currently working on his MSc in Philosophy, Science and Religion at the University of Edinburgh. Prior to his academic career, Michael played nine years in the NFL with the New York Jets and the Kansas City Chiefs. He currently lives in Bangor, Maine with his wife and two sons.

by Steve | Sep 3, 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September-October 2019

Rachael Porter and the Rev. David Johnston adopted two children who came from a home with opioid addiction. Johnston serves as pastor of Concord United Methodist Church in Athens, West Virginia. Photo by Mike DuBose, UM News Service.

By Joey Butler (UMNS) –

Rachael Porter and the Rev. David Johnston seemed destined to be foster parents. The couple met while on staff at a United Methodist summer camp, and there were always a few foster children in attendance.

One 9-year-old in particular, Johnston said, “would pick his scabs off just for the few moments of love and attention” he would get from a counselor. “It just struck something in me,” he said. “As a way of expressing God’s love of us, needing to show that to kids who wonder, ‘Is there enough love for me?’”

Porter said she’d felt a desire to adopt since middle school after reading “A Child Called It,” which documented the author’s upbringing in an abusive home. “I wanted to wait five years after we were married before we thought about having kids, though,” she said.

That five-year mark coincided with the couple’s move to West Virginia, where Johnston was appointed pastor of Concord United Methodist Church in Athens. Their very first week, they were invited to a cookout and encountered a woman who works as a home finder for Children’s Home Society.

The next thing they knew, they were registered for parenting classes and going through background checks. After learning about the great need for foster parents — West Virginia has one of the highest rates in the nation for children being removed from their homes due to drug addiction — they opted for that route over adoption.

The Friday before Ash Wednesday 2017, the call came and just like that, two more plates were set for dinner. The children, a brother and sister aged 4 and 5, had already been in the foster care system for over two years, coming from a home with opioid addiction. This was to be their sixth placement. “Moving was so much a part of their lives that after a few months one of them said, ‘OK, I’m ready to move to the new house now,’” Johnston said.

Questions about why they couldn’t live with their biological mother were also tough to hear, but Porter said honesty was the best policy. “I told them that their mom was addicted to drugs and she wasn’t able to make right decisions and take care of them like she should, so they had to come be with somebody who could take care of them,” she said.

The Revs. Matt and Beth Johnson have a similar story. They also answered the call to become foster parents to children living in what Matt called “a rough situation.” After a two-year process, in April 2017 they were able to adopt the brother and sister they were fostering.

“Our kids came in July, so we had a big Christmas that year,” said Matt, who is associate pastor at Suncrest United Methodist in Morgantown. “After opening presents, our girl, who was 4 at the time, looked at us and asked, ‘Will I live with you next Christmas?’ It was heartbreaking. All we could say was I hope so.”

Beth Johnson, Wesley Foundation director at West Virginia University in Morgantown, said becoming a foster parent means helping the children cope with issues of trauma, neglect, or abandonment they may experience. “The question became, ‘Am I willing to absorb your suffering and walk through that together?’ It’s a redemption story being written,” she said.

“Some nights after a tough day, we’d sit and ask, ‘Can we do this?’ It’s by the grace of God that we never both said no at the same time,” Matt said.

Both couples acknowledged how much love and support they’ve received from their congregations. “It’s almost like they have half a dozen grandparents at this church,” Johnston said.

Having a group of potential sitters is also helpful, but it’s not quite that simple. Anyone the children are left with must likely undergo a background check; some agencies require sitters to go through the same certification process as the foster parents. However, there is always a need for extra help with errands, or providing material needs for the kids. A few retired teachers even help with homework.

“If someone in your church is considering fostering, find ways to help them,” Matt Johnson said. “Stand up and say, ‘We’re not letting them do this by themselves.’” Johnson recalled the whirlwind the day their children arrived, and the fear of not having everything the children needed. “You don’t know what, if anything, they’ll show up with, or what size clothes or shoes they wear,” he said. “We had to call people and say, ‘I have a list of things, can you help us and run to Target right now?’”

Porter and Johnston insist that, though it can sound daunting, their experience as foster parents has been rewarding. And on February 1, they officially adopted their children. “It’s amazing how much joy these kids have. After what they’ve been through, they laugh constantly,” she said.

Johnston said the way his church has embraced the children is a blessing, as is seeing them “starting to learn the rituals of worship and the words, and knowing that they’re coming to know the story.”

There are numerous opportunities out there for people willing to care for children in these situations — and not only for young kids. Teens also need someone to help them with school or with life decisions they will soon have to make. Those who age out of the system may have nowhere to go and could use a network of support.

“I wouldn’t say that just anybody should do it, though there’s such great need. It’s got to be a calling,” Porter said, adding that she and Johnston are always honest and careful not to romanticize the experience when talking to others.

Johnston said having an “even-keel” personality is a huge help. “It’s hard work. There’s constant paperwork, contact with case workers, therapy. You have to be an advocate for them, particularly at school. You need a network of people to support you, who you can be vulnerable with about how hard it is.”

Porter said as their adoption came closer to being official, her children stopped asking about moving. They started referring to their “forever home.”

Joey Butler is a multimedia producer/editor for United Methodist News Service.