by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Leonard E. Fairley

Mourners at the corner of 38th and Chicago in Minneapolis – the location of George Floyd’s death. Photo by David Parks.

“What Started Out As A Peaceful Protest Turned Violent,” “Seven Shot in Louisville Demonstration Against Breonna Taylor’s Death,” “Chaotic Minneapolis Protests Spread Amid Emotional Calls For Justice, Peace,” “Protest Turns Violent!”

These are the headlines we’ve been waking up to lately. Like many of you, I read these headlines with a broken, devastated, and troubled heart, a heart that was already breaking due to the death of three people of color who should be alive – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

As an African American male, I felt these deaths on an intimate level because I know firsthand what the evil of racism feels and looks like. My heart wept at the sight of an effigy hanging right here in Kentucky: As an African American male, I felt the historic pain of countless brown- and black-skinned people hanging from lynching trees. My heart wept when an African American bird watcher suffered the threat of harm by having the police called on him. This list could go on and on.

We must not dishonor the memories of these souls by practicing the spirit of an eye for eye and a tooth for tooth. We must not dishonor their memories by causing more blood to run though our streets or the destruction of property to occur. These deaths deserve better.

My heart also weeps when protesting for right becomes the face of the very evil, injustice, and oppression it tries to eliminate and call attention to. It has, and will in the days ahead, become incumbent on all of us to nonviolently work toward driving from our communities, nation, and world the hatred, violence, and injustice, caused by racism or any other “ism” that fosters prejudice and oppression.

In our heart of hearts, we know none of these evils are from God. We as Christian disciples of Jesus Christ shouldn’t accept them as normal. We must together fight them with hearts and actions of peace, not war.

I acknowledge that much of the protesting comes from pent-up frustration and disappointment. We have a right to be disappointed when a life is taken needlessly and unjustly. It is never easy to suffer injustice and not become bitter when you feel your only recourse is protest. “It is always right to protest for right,” Martin Luther King said.

However, protesting for right doesn’t mean we replace one violent act for another. Violence is a vicious cycle that leaves only victims. Again, we cannot allow our protesting for right to simply become another face of the wrong or injustice we’re protesting. We cannot live by trading one form of bitterness and violence for another. Hatred, vitriolic words, chants, or slogans are never the answer. Hatred, violence, and injustice are cycles that feed on each other. King also said, “Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

“I am weary from my moaning; every night I flood my bed with tears; I drench my couch with weeping.” – Psalm 31:9-10. Like the psalmist, we grow weary of all the violence, all the hatred, and all the polarization and division.

I think people have grown immune to voices that can write eloquent statements that come with a title and office such as a Bishop. One would expect me to respond. Yet how can I live into my role as Bishop and shepherd and remain silent? What we long for and must hear are the actions and voices of passionate, spiritual disciples who have a desire to do right – a desire to do God’s will as we pray, “deliver us from evil.” We long for voices of people who have never spoken out against anything and would never dare join a protest or write a political statement or get lost in social media battles.

Brothers and sisters in Christ, what is happening in our world, our communities, and our nation goes far beyond politics or labels. Christian people of goodwill must find their voices or we will continue to fall deeper into this darkness. Somehow our voices of hope, peace, love, and kindness must rise from the ashes and help swing this pendulum toward what the Lord requires of all of us who dare call ourselves followers of Jesus Christ. “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8).

Somehow the spirit of Jesus that lives in you must rise up in all humility and proclaim in his name: Enough is enough. “Come, Lord Jesus, come” and show us how to live with each other, reminding us that there is a more excellent way.

I have little left but grief and heartache. Yet, with every ounce of my one hope, I pray we will learn that all cops are not bad, all black men are not thugs, and racism is a disease that must be admitted before it can be cured.

I appeal to the Christian conscience of every passionate, spiritual disciple and sisters and brothers in Christ to join my spirit and say, “Not like this!” Stop the police killings. Stop the racism. Stop the divisive and vitriolic language. Stop the injustice. Stop the destructive protest. Protest we must, but not like this.

Let us rise up and tell the world, the nation, every perpetrator spreading injustice, every perpetrator spreading hatred, death, and violence, that this is not the way. There is still a more excellent way to rise up and tell this divided world and nation that his name is Jesus, bringer of peace and healer with the power of reconciliation and redemptive sacrificial agape (love), as the only true light in darkness.

Help us to remember in these dark days, as King said, “At the center of non-violence stands the principle of love.”

“Be gracious to [us], O Lord, for [we are] in distress; [our] eyes waste away with grief, [our] soul and body also” (Psalm 31:9).

Leonard E. Fairley is the episcopal leader of the Kentucky Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church. This statement was issued by Bishop Fairley on May 30, 2020, and is reprinted here by permission.

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Bishop Gregory V. Palmer of the West Ohio Annual Conference delivers the episcopal address during the 2016 United Methodist General Conference in Portland, Oregon. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

“What a season we have been through and what a week we are in,” wrote Bishop Gregory V. Palmer to the United Methodists in the West Ohio Annual Conference. “The angst and pain are palpable. I need you to know I share that pain and I see me in some way, shape, or form every time I see video clips from Minneapolis and around the country. I have no illusion. It could have been me. That’s the world in which we live.

“The death of George Floyd is a painful sequel to much that we have seen before,” Palmer continued. “God help us if you please. I grieve for the Floyd family and all the families that have had the same or similar experience. God heal their hearts. I shudder as I watch the burning in Minneapolis, but I do watch and choose not to look away. Looking away perpetuates avoidance. I look not to condone but to be drawn deeper into the compassionate heart of Jesus our savior. Lord give us eyes to see.”

Within our society and around the world, the horrific deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have sparked passionate protest, intense soul-searching, and purposeful prayer. At this time, Christians are looking for ways to be a faithful witness to the Gospel of our Lord Jesus and his kingdom of compassion, righteousness, and justice.

“It is time to use our voices, our pens, our feet, and our heart for change,” the United Methodist Council of Bishops expressed in a statement, signed by Bishop Cynthia Fierro Harvey, president of the council. The bishops encouraged United Methodists to spend eight minutes and 46 seconds in prayer at 8:46 a.m. and 8:46 p.m. each day for a 30 day period. The time allocations are in remembrance of George Floyd who was killed on May 25 when a police officer kneeled on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds in Minneapolis.

“Pray for all persons of color who suffer at the hands of injustice and oppression. Pray for our church as we take a stand against racism,” the statement reads. “Imagine the power of a concert of prayer heard around the world.”

During this tumultuous time of both social distancing and social upheaval, we are called to act, pray, and love our neighbors. During this time, several bishops have reflected on the issues confronting our society and the call to justice.

• Bishop Sharma Lewis, Virginia

“When do we as children of God decide that God is calling us into action? When do we decide that mere words or social media interactions for a few days are just not enough?

“When do we as children of God decide that the systemic racism in our society, whether manifested overtly or covertly, is a sin that hinders our relationship with Jesus Christ and is antithetical to the gospel?”

• Bishop Bruce R. Ough, Dakotas-Minnesota

“Now, it is our responsibility as persons of faith, and particularly as followers of Jesus in the Methodist tradition, to address this pervasive pandemic of racism. We are compelled to address this pandemic with the same intensity and intentionality with which we are addressing COVID-19.

“We begin by acknowledging that racism is sin and antithetical to the gospel. We confess and denounce our own complicity. We take a stand against any and all expressions of racism and white supremacy, beginning with the racial, cultural, and class disparities in our state and country that are highlighted by the coronavirus pandemic.”

• Bishop Jonathan Holston, South Carolina

“As United Methodists and followers of Christ, we commit ourselves to social justice and to opposing racism in all of its forms. We encourage frank and thoughtful conversation and respectful collaboration with a common goal of justice for all. It is our obligation to be a beacon of love when hatred threatens to blot out the light of hope.”

“As United Methodists and followers of Christ, we commit ourselves to social justice and to opposing racism in all of its forms. We encourage frank and thoughtful conversation and respectful collaboration with a common goal of justice for all. It is our obligation to be a beacon of love when hatred threatens to blot out the light of hope.”

Bishop Holston wrote in a later statement, “When we witness inexplicable injustice, anger is understandable, protest is appropriate, and action is vital. Violence and destruction, though, is never the answer.

“We are encouraged to see people flood the streets to peacefully call for justice and an end to oppression. This is faith in action – the bedrock of our commitment to social justice as United Methodists and followers of Christ.”

• Bishop Frank Beard, Illinois Great Rivers

“It is the job of every Christian to serve as conduits of grace, mercy, and love so that the dark forces of our world might experience the liberating light of Jesus Christ. It is our job to help stamp out hatred in any form. Therefore, I encourage all United Methodists to pray for the families that are affected by this most recent tragedy, as well as those suffering a similar plight in recent months. I remind us all that it is our duty, as sisters and brothers, to stand-up, speak-out, and advocate for those that are hurting and marginalized, so that justice may become a reality.”

In a separate statement, Bishop Beard offered practical suggestions as we wrestle with the issues of race, prejudice, and injustice.

“Dealing with racism is not easy and it takes a lot of energy and forethought that will often move us into uncomfortable places. Speaking up and out is important, even though people often are scared to say anything because they worry that if they say the wrong thing, they might get in trouble or find themselves being labeled. It is crucial for Christians to create safe sanctuaries where we can have difficult conversations about racism and other topics that promote injustice.”

Beard offered 10 ways that Christians can begin to “address systemic injustice and discrimination.”

1. Becoming aware of policies and practices that promote disparities based on race, ethnicity, stereotypes, or economic status.

2. By employing the use of empathetic listening that is engaging and helps with validating the feelings and personal experiences of persons of color, without being dismissive or making explanatory comments that seek to rationalize or soothe away their pain.

3. Learn to recognize and understand your own privilege and experiences that are based on skin color and power.

4. Share your own story as you engage in tough conversations about race and injustice. Your story will help foster deeper understanding for you and for others as you interact together.

5. Recognize that America is NOT a “melting pot” but rather a “garden salad” containing a blend of unique colors and flavors meant to be experienced together. DO Not give in to the myth that you must be “color blind.”

6. Seek to identify with those that are marginalized and who face the effects of a system that thrives and survives on racist behavior and practices.

7. Use the power of your own personal finances by taking a stand with your money. Be aware of the practices of those you do business with.

8. Create safe places for difficult conversations, utilizing people experienced in providing diversity training.

9. Develop and foster relationships with people of color based on mutual respect and concern for each other’s well-being.

10. As people of faith, pray for and with others, that Jesus’ prayer for unity would become a reality.

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Keith Boyette –

Mourners and protesters gather at the corner of 38th and Chicago in Minneapolis – the place of George Floyd’s death – to reflect, grieve, and hear the message during a service sponsored by the Worldwide Outreach for Christ – a church in that neighborhood for 38 years. The congregation hosted open-air evangelistic and prayer services for those in the community. Photo by David Parks.

At its founding in its Statement of Moral Principles, the Wesleyan Covenant Association declared, “We believe that all persons are of sacred worth…. The WCA specifically renounces all racial and ethnic discrimination and commits itself to work toward full racial and ethnic equality in the church and in society.” Recent events in the United States underscore how absolutely critical this work is.

We are outraged by the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. The horrific taking of each of their lives cries out for justice. Yet what they experienced were not isolated incidents. Racism, systemic injustice, and the use of force leading to the killing of African Americans is an affront to God’s good gift of life and human dignity. It has no place in the body of Christ or in any society that aspires to reflect the character of Jesus. It is sin.

As Christians we are called to relentlessly work for a society where African Americans no longer have to fear for their lives or be treated differently when encountered by law enforcement, or when they are simply going about the business of their daily lives. We must dedicate ourselves to building a church that bears witness to the dignity of all God’s people, particularly those who have been marginalized, stereotyped, and treated with cruelty and violence based on the color of their skin. The church must summon every fiber of its being to root out racism in its midst. Collectively and individually, we must examine our hearts, our minds, our institutions, and our practices, and, with unwavering determination, stamp out racism.

The battle against the evil of racism requires far more than an occasional statement or symbolic ceremony. Rooting out the conscious and unconscious ways in which we diminish others requires perseverance and disciplined focus. We must continually call ourselves to account. We must empower others to speak truth into each of our lives. There is no room for rationalization or justification. The work requires persistent, sacrificial discipline proactively engaging our own prejudices, biases, and actions, and engaging the ways in which those prejudices and biases have found expression in the systems of which we are a part. The work calls us to intervene and speak up when we are witnesses to racism and systemic injustice. We must overturn systemic injustices.

At its foundation, Scripture calls us to acknowledge that every person we encounter is made in the image of God – nothing diminishes or obviates that reality. Therefore we Christians must accord all people their human dignity, defend their God-given rights, and see that justice is done for them just as we expect it to be done for ourselves.

In recent days, I read again the words of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in his “I Have A Dream” speech delivered on August 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. He declared, “Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley… to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.”

Sadly, we have failed to “make justice a reality for all God’s children.” We must acknowledge our failure and redouble our commitment to work toward full racial and ethnic equality in the church and in society. Let us not relent or rest until we have achieved that reality.

Keith Boyette is president of the Wesleyan Covenant Association and an elder in the Virginia Conference of The United Methodist Church.

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

Photos by David Parks –

Jonathan Tremaine (JT) Thomas of Civil Righteousness, a ministry out of Ferguson, Missouri.

In the midst of waves of protests around the globe in response to the death of George Floyd, there were also worship services in communities that brought Christians of different ethnicities together to sing and pray, mourn and lament.

In the week after Floyd’s death, open-air services were conducted at the street corner of 38th and Chicago in South Minneapolis – the site of Floyd’s death – featuring gospel music, evangelistic preaching, calls for racial justice, Christian reconciliation, and the infilling of the Holy Spirit.

The services were launched by Pastor Curtis Farrar of the Worldwide Outreach for Christ, a congregation located at the street corner for 38 years. As protesters and mourners flocked to the memorial site, Farrar’s congregation offered free water, food, and antiseptic spray. From a street corner platform, he preached and members of his congregation led worship and prayer. Farrar was also joined by young evangelists such as Christophe Ulysse of Youth With a Mission (YWAM); Yasmin Pierce with Circuit Riders, a ministry from Southern

California; and Jonathan Tremaine (JT) Thomas of Civil Righteousness in Ferguson, Missouri.

“I’m seeing that people are responding in a positive way,” Farrar told a television station in Minneapolis. “I’ve never seen so many people come together on this corner. I’ve been here 38 years and I can see the peace and camaraderie and everyone’s helping one another.”

“This is a wakeup call to the world that we’re all morally bankrupt apart from God,” Ulysse told the Brantford Expositor. “There are so many narratives that are trying to hijack what’s going on. But this racism is a deep thing that we need a higher power to address.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”

Working with Farrar, Ulysse said that, during his time at the Floyd memorial, he saw hearts “turn from hatred, resentment, bitterness, and hopelessness,” as people of different races wept and hugged each other. He hoped that his message to the protesters and mourners would ultimately empower them to be “carriers of hope.”

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Courtney Lott –

Original art by Sam Wedelich (www.samwedelich.com).

“Greet all God’s people in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 4:21)

It’s the simplest phrase tacked on to the end of a letter. One we possibly pass by quickly, viewing it as a nice sentiment, and little else. We may even believe it’s a command easily and painlessly applied to our lives. Definitely not one that needs a closer look.

Sure. I’ll say hello to the people at my church. Box checked. Dust off hands. Done. Here in Texas, we pride ourselves on welcome, after all. It’s deeply ingrained in our culture. Even in the big cities and traffic jams, strangers wave to each other, smile (which has been a lot more difficult while wearing masks during COVID!)

But is it really so simple?

A box easily ticked off? A bland sentiment? Or does it dig deep into what it means to be part of the bride of Christ? Considering the fact that Paul uses it in the closing of multiple letters to multiple churches, chances are, it’s not a simple admonishment we ought to skim over.

Beyond the literal meaning of the Greek word for “greet” — “welcome” — the heart of the concept strikes deep to a desire ingrained in all of us: to not only be acknowledged by others, but to be welcomed in, to be seen without filters and still accepted. For a moment of eye-contact, a genuine question after one’s well-being, true interest in what makes you a unique image bearer.

Throughout my childhood, I often felt brushed aside. I was weird. I’m still weird. My overactive imagination — and sensitive spirit — categorized me as an oddball most of my peers either avoided or teased. I usually didn’t feel welcome at school, and at one point, begged my mom to teach me at home so I could avoid these painful interactions.

This lack of greeting left me with a deep sense that I didn’t belong, that no one wanted me around, and that there was something innately wrong with who I was. I hid myself away in books and stories, seeking out an imaginary community where I was accepted fully, weirdness and all.

I prayed nightly for a friend. For one who loved me as David loved Jonathan. Someone whose soul knit itself to mine. I have distinct memories of asking God to send me a peer who would not only share in my similar interests, laugh with me, cry with me, but who would call me out on things, make me better.

Then, in junior high of all places, the youth of my church opened their arms to me. In our mutual awkwardness of puberty, pimples, and prepubescent pensiveness, we found community with each other as we played stupid messy games and — still sticky with random food items — delved into the pages of scripture.

For the first time in my entire life — inside and out of the four walls of a church building — I found a sense of home, belonging, purpose. This simple act of kindness didn’t heal all of my insecurities, most of which still live in my heart as ugly weeds, but it healed much within me, strengthened me to do the same for others.

Thus empowered, making others feel welcome became a large part of my mission in life. It hasn’t always been easy. My own insecurities sometimes still tempt me to sidestep “weirdos” lest my association with them make me unwelcome again. When this temptation comes, I have to remind myself of what has been done for me, of my own little story of social salvation.

My experience hardly reflects the intense sense of misery others have experienced when it comes to rejection. Those who have experienced racism or discrimination due to their sexuality have suffered deeply and in ways I can’t even begin to imagine. The path they walk is a unique kind of pain I’m not familiar with.

The solution to our problems, however, looks very similar, and it’s found in this beautiful verse. Greet all God’s people in Christ Jesus. Greeting someone affirms the dignity already present in our fellow image bearers. It acknowledges that we are all messed up, but that if Jesus can love us that way, we can love each other that way as well.

Sometimes, like the religious leaders in Jesus’ parable about the good Samaritan, we sidestep those we view as “unclean.” As if their unique brand of sin will rub off on us if we get too close. When we are tempted to fall into this, we are called to remember how Jesus dealt with the “unclean.”

He touched lepers, curing them of their disease. He gripped the hands of those long dead, filling them again with life. He cleaned his disciples’ nasty feet. Jesus drew near to those everyone else would have avoided, in a sense, welcoming those no one else would. He did what the rest of us couldn’t do.

If anyone else embraced one of these, they wouldn’t be able to enter the temple, to step foot near the presence of YAHWEH. But Jesus’ simple touch cleansed, healed. Ultimately, he became unclean for us, making a way for us to approach the Holy God of the universe.

By his wounds we are healed.

By his uncleanness, we are made clean.

By his welcome, we are welcomed.

May we go and do likewise.

Courtney Lott is the editorial assitant at Good News.

by Steve | Jul 8, 2020 | July-August 2020, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Jim Patterson

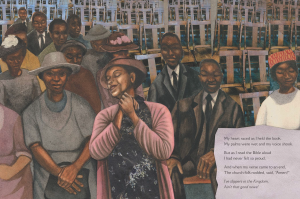

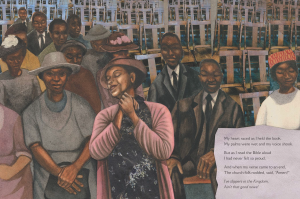

Art from the book By and By: Charles Albert Tindley, The Father of Gospel Music, written by Carole Boston Weatherford and illustrated by Bryan Collier. Image: Simon & Shuster.

Disbelief is the most satisfying response Carole Boston Weatherford gets from children about her books featuring notable African Americans.

“Kids just can’t believe that our nation allowed those kinds of injustices to visit upon so many people,” said Weatherford, a poet who has written children’s books on Fannie Lou Hamer, Harriet Tubman, Lena Horne, and others.

“I want them to be appalled,” she said. “I want them to be shocked that (slavery and racial discrimination) happened, but I also want them to be inspired that my subjects overcame those injustices … and persisted in reaching their potential and in making contributions to their communities and to larger society.”

Weatherford, who grew up as a United Methodist and was married for 20-some years to a United Methodist minister, considers it a mission to help correct the dearth of books about African Americans she experienced growing up.

“There were hardly any,” she said. “But when I became a mother, I noticed that there were more books that featured children of color for them.”

Her latest subject is Charles A. Tindley, a Methodist Episcopal clergyman sometimes called “The Prince of Preachers” and one of the founding fathers of gospel music. He was pastor of East Calvary Methodist Church in Philadelphia — now named Tindley Temple United Methodist Church — from 1902 to 1933.

His hymn, “I’ll Overcome Someday,” was one of the roots of the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” He wrote other gospel music standards, such as “(Take Your Burden to the Lord and) Leave It There,” “Stand by Me” and “What Are They Doing in Heaven?”

Tindley, born in 1851 the child of a slave father and a free mother who died young, received no formal schooling as a child — instead being hired out as a field hand. He taught himself to read from newspaper clippings lit by glowing pine knots.

Pursuing whatever education he could afford — night schools and correspondence courses, mostly — while working to support himself, he relocated to Philadelphia with his wife, Daisy, and worked as a church custodian. From there, he progressed to being the pastor of the very same church and writing many memorable gospel songs.

In By and By: Charles Albert Tindley, The Father of Gospel Music, illustrated by Bryan Collier, Tindley’s rather incredible rise is told in lilting verse by Weatherford.

“My life is a sermon inside a song/I’ll sing it for you/Won’t take long,” the book opens.

The illustrations by Collier are vivid and striking, mixing collage and watercolor painting. He has illustrated many children’s books about African Americans including Rosa Parks, Langston Hughes, Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, and contemporary musician Trombone Shorty.

“I think Tindley is a testimony to endurance and aspiration,” Collier said. “His insatiable need to learn and read, you can see that theme through a lot of different people like Frederick Douglass and many others growing up in the era of America that he grew up in, when the odds were totally against them to do what he did.”

Collier said his illustration style is influenced by his grandmother, who made quilts when he was a kid. “That’s the collage aspect of it. I try to use earth tones and bright colors for juxtaposition to make it pop. I use family members and friends to pose for the book, so we see ourselves and they can see themselves in books.”

Collier used to play as a child in an abandoned Pocomoke City, Maryland, church named for Tindley. It has since been torn down. Tindley was born in Berlin, Maryland, about 30 miles north of Pocomoke City.

“Every year, they do Tindley Day in Maryland as well as in Philadelphia,” he said. “So I had known about it and had been at the celebration picnics on Tindley Day.”

Collier has projects coming up about a mother’s writing directed to her unborn son and a reinterpretation of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.”

Weatherford is working on a book about Henry Box Brown, who in 1849 mailed himself in a wooden box from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia to escape slavery.

No matter how much historical context Weatherford shares when addressing children about her books, she says many are “confused” and ask the same questions:

“Did it really happen?”

“Who made those stupid rules?”

“Why did white people treat black people so badly?”

“They’re constantly trying to figure out how they should respond to history and also to injustices they see in their own lives,” she said. “Bullying in school, how do I respond to that? So kids are learning to navigate situations and they are forming their own values.

“I do hope that my books play some role in shaping their values and helps them form their own system of justice.”

Jim Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee.

“As United Methodists and followers of Christ, we commit ourselves to social justice and to opposing racism in all of its forms. We encourage frank and thoughtful conversation and respectful collaboration with a common goal of justice for all. It is our obligation to be a beacon of love when hatred threatens to blot out the light of hope.”

“As United Methodists and followers of Christ, we commit ourselves to social justice and to opposing racism in all of its forms. We encourage frank and thoughtful conversation and respectful collaboration with a common goal of justice for all. It is our obligation to be a beacon of love when hatred threatens to blot out the light of hope.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”

Ulysse, who lives in Hawaii, was born to mixed-race parents. “I have the advantage of being bi-racial so I can understand the beauty of both worlds and be a bridge,” he said. “My dad taught me if people called me the N-word, it was because they had never really met one of us. So, it’s our place to educate them and show them what we are really about. To the ignorant, we must become ambassadors.”