by Steve | Apr 22, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

The United Methodist Church is currently in an extremely awkward position. The vast majority of church leaders acknowledge the need for separation to take place in order to resolve the decades-long controversy over biblical authority and interpretation, sexual ethics, and the definition of marriage (among other topics). A Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation was negotiated and appeared to have broad support across the church in 2020. The pandemic has interfered, causing the postponement of the 2020 General Conference, which was set to potentially adopt the Protocol. Now, the General Conference will not meet until 2024.

There is now no clear, denomination-wide process for local churches to disaffiliate from the UM Church in order to align with the Global Methodist Church. We thought by adopting ¶ 2553 (the Taylor disaffiliation plan) in 2019, that the General Conference had created such a consistent process. However, the way ¶ 2553 is being applied, every annual conference can make its own rules about what is required for a local church to move to the GM Church. In effect, there are 50 different sets of rules in the United States for local churches to follow. And the various annual conferences outside the U.S. are in different situations, operating under their own sets of rules and legalities.

In the absence of a clear, denomination-wide process for disaffiliation, many traditionalists are feeling “stuck” in a denomination that has abandoned what they believe and stand for, particularly in the U.S. It is important to understand the factors creating this “stuck” feeling and to move toward addressing the causes. Only as an amicable separation is able to take place will The United Methodist Church, as a whole and all its parts, be able to move forward into a new and more faithful reality (regardless of which perspective people hold on our issues of disagreement).

Lack of Information

One of the factors in a feeling of “stuckness” is the lack of information being shared. Many average church members have been unaware of the depth of the division within the UM Church. Many clergy have bent over backwards not to tell them what has been going on. With the announcement that the Global Methodist Church is launching, there are many laity saying, “Wait – what?!” It is important for clergy and lay leaders in local churches to inform their people about the issues dividing our denomination and the potential for separation. Being kept in the dark creates feelings of powerlessness and mistrust among members toward their leaders.

Information is available on the Good News website and on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website that delves into the issues around separation. Most of my articles are collected on my blog site for people to read, and they cover the issues involved over the past several years.

Even more problematic is the lack of information about the process of separation for local churches. Once a church wants to explore its options, those options must be explained in a way that allows for church leaders and congregations to make informed decisions. UM News Service has a comprehensive article that helps understand the process of disaffiliation in general. Wespath (the church’s pension board) has prepared information about disaffiliation and how it affects clergy and congregations in relation to the pension program. Other general information about disaffiliation is available on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website, including information about the Global Methodist Church, for which you can also see the GM Church website.

This is all good general information, but the problem I mentioned above is that there are different rules for disaffiliation for each annual conference. Many annual conferences have not published their unique rules or made them available even on request. In some annual conferences, repeated calls to the conference office go unreturned. Again, where people are kept in the dark, they feel helpless and “stuck.”

One important piece of information is how much money a church would owe in order to disaffiliate. Under the prevailing rules of ¶ 2553 enacted in 2019, a church must pay two years’ worth of apportionments and its share of the annual conference’s unfunded pension liability. That pension liability payment is calculated individually for each congregation by its annual conference. Yet, many annual conferences are not making that payment amount available to congregations, even when they request it.

The North Georgia Annual Conference has taken the lead by publishing that pension liability payment for each local church on its website. An annual conference receives its pension liability number from Wespath each year in the fall. It can then allocate the local church’s share of that pension liability using a formula determined by the annual conference. Most often, this is the apportionment formula, but various annual conferences use different formulas to calculate the individual congregation’s share.

It is unfortunate that many annual conferences are refusing to make that number available to their local churches in a timely way when they request it. This is a simple math problem. The number for all local churches in an annual conference could be calculated in an afternoon. Yet, some conferences are holding on to that information and keeping their churches in the dark. The local church is then “stuck” because it cannot move forward toward making a decision on disaffiliation without knowing how much it is going to cost.

Delay

Another factor in causing the feeling of “stuckness” among traditionalists is that some bishops and annual conferences are refusing to move forward with the disaffiliation process, even though it is outlined in the Book of Discipline. Several annual conferences are not moving forward with disaffiliations this year because they have yet to figure out their rules to govern the process. This is despite the fact that ¶ 2553 has been the law of the church since 2019. At the very least, this situation betrays the level of incompetence among some annual conference leaders in failing to consider and develop plans in a timely way for local churches to disaffiliate. (One hope for the Global Methodist Church is that it will be much more nimble, able to respond to changing circumstances rapidly and anticipating needs and planning for them ahead of time.)

A more nefarious motivation may be behind some delay tactics. Some annual conference leaders may be hoping to make the process so long and torturous that local churches give up and remain within the UM Church. One district superintendent responded to a request for disaffiliation from a local church by saying that his district already had several churches disaffiliating this year and he did not have time to deal with more. So this church would just have to wait until next year. Other superintendents have refused to schedule a church conference to vote on disaffiliation when requested to do so by the local church. After all, the longer it takes a church to disaffiliate, the longer that church will contribute its apportionments to support the annual conference. Of course, that assumes congregations will be willing to continue paying apportionments in the face of what appears to be bad faith actions.

The failure of some annual conferences to draft the rules for local church disaffiliation can fall under this delay category, as well. Some annual conferences are saying, “Sorry, we have to draw up the rules and then they have to be approved by this year’s annual conference in order to take effect. You will have to wait until next year to disaffiliate.” Again, conferences have had three years to draw up their rules for disaffiliation, and the failure to do so, even amid the pandemic, is inexcusable. Some conferences are finding a way to work around this by holding a special annual conference session later in the year to deal with disaffiliating congregations. Others could do the same.

These delay tactics will not cause traditionalists to want to remain United Methodist. If anything, they will reinforce traditionalists’ desire to move into a new denomination that is more responsive and provides better leadership. Unfortunately, some traditionalists will not be willing to wait for the annual conference to get its act together. Individual members may just decide to give up and go down the road to another denomination’s church that is in line with their beliefs. That will, of course, weaken the traditionalist UM congregation. It also plays into the hands of the annual conference, which could then potentially send in a liberal pastor to shift the congregation in a more theologically progressive direction, hoping to keep it in the UM Church. Or, if the church declines too much, the conference will just close the church, sell the property, and live longer off the legacy of resources accumulated by traditionalist congregations.

In any event, the delay makes that congregation feel “stuck.” It cannot move forward because of the roadblocks put up by its annual conference.

Egregious Financial Payments

A final factor in keeping traditionalists feeling “stuck” is the imposition of egregious financial payments on a disaffiliating congregation. The requirements of ¶ 2553 amount to roughly six to nine times the congregation’s annual apportionment figure. Many churches find it challenging to raise that amount of money in a lump sum to be paid at the time of disaffiliation. Some congregations resort to borrowing the funds from a bank, from the UM Foundation, or from their members. Of course, that imposes a long-term drag on the church’s ability to fund ministry, but at least it gets them into a more desirable denominational situation. But if they cannot raise the funds or are unwilling to pay that amount, they will be stuck.

On top of that already challenging financial payment, some annual conferences are requiring local churches to pay additional costs. Most egregiously, some are charging a percentage of the church’s appraised property value (anywhere from 20 to 50 percent). One conference is even trying to get 50 percent of all the church’s assets, including mission funds, local foundation, memorial funds, etc.

Essentially, these annual conferences want their disaffiliating congregations to pay twice for the facilities they will carry into the new denomination. In many cases, those congregations have been faithfully paying into the conference apportionments and program for decades, and the annual conference has put none of its own money into those congregations. To charge congregations for a percentage of their facilities is grossly unfair and amounts to a “poison pill” that effectively prevents a congregation from departing. For most churches, there is no way for them to raise the kind of money that would double purchase their buildings and assets.

These egregious financial payments again make traditionalists feel “stuck” and unable to change their congregation’s denominational alignment.

The Consequences of “Stuckness”

To the extent that UM leaders are pursuing a strategy to slow-walk disaffiliation in hopes of keeping traditionalists “stuck,” it is a strategy that could backfire. Weakening local churches serves neither the interests of the UM Church nor the GM Church. Nor does it advance the work of God’s Kingdom.

Keeping unwilling traditionalists boxed into the UM Church only increases resentment toward the denomination and jeopardizes continued apportionment payments and other forms of participation and engagement in the work of the church. It also prevents centrists and progressives from moving forward with their agenda to change the UM Church in a more progressive direction. Instead, it is in the interest of centrists and progressives to allow traditionalists a clear and feasible pathway to disaffiliate. Only as congregations are sorted out to where they want to be will both denominations be able to put the conflict behind them and move forward into a positive future. Here’s to hoping that the “stuckness” ends soon!

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo by Shutterstock.

by Steve | Apr 21, 2022 | In the News

Lloyd J. Lunceford

Church Trust Law Webinar: Tuesday, May 10, 7 PM Central Time

***

Do United Methodist congregations own their buildings?

What is a trust?

Can the United Methodist trust be revoked?

Is there a legal process for disaffiliating from the UM Church separate from what is in the Book of Discipline?

When might it make sense to use the legal process, rather than the Discipline’s process?

When might a local church need an attorney, and when might it not need one?

What steps should a local church take to prepare for disaffiliation?

During this confusing time in The United Methodist Church, it is important to have clear, factual answers to the many questions surrounding disaffiliation. Good News is sponsoring a Webinar to help answer these and other questions and provide helpful information. Understanding church trust law can help your church discern when it is appropriate to use an attorney and when it is not needed.

The presenter will be Lloyd Lunceford, Esq. of the firm Taylor Porter in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He has practiced law since 1984, with emphases in higher education, mass communications, commercial litigation, and church property laws. He served for many years on the board of the Presbyterian Lay Committee, the Presbyterian equivalent of Good News. He was involved in many church property cases during the separation of the Presbyterian Church (USA) and has a wealth of knowledge and experience in this area. You can read more about him at https://www.taylorporter.com/our-attorneys/lloyd-j-lunceford

To participate in the webinar, please use this Zoom link below:

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/89831892524?pwd=ZEpNZzFxWm5GcUdCR05BVlh5V0p5Zz09

Meeting ID: 898 3189 2524

Passcode: 869881

If you have any questions, please contact the Rev. Tom Lambrecht at tlambrecht@goodnewsmag.org

by Steve | Apr 15, 2022 | In the News

By Shannon Vowell

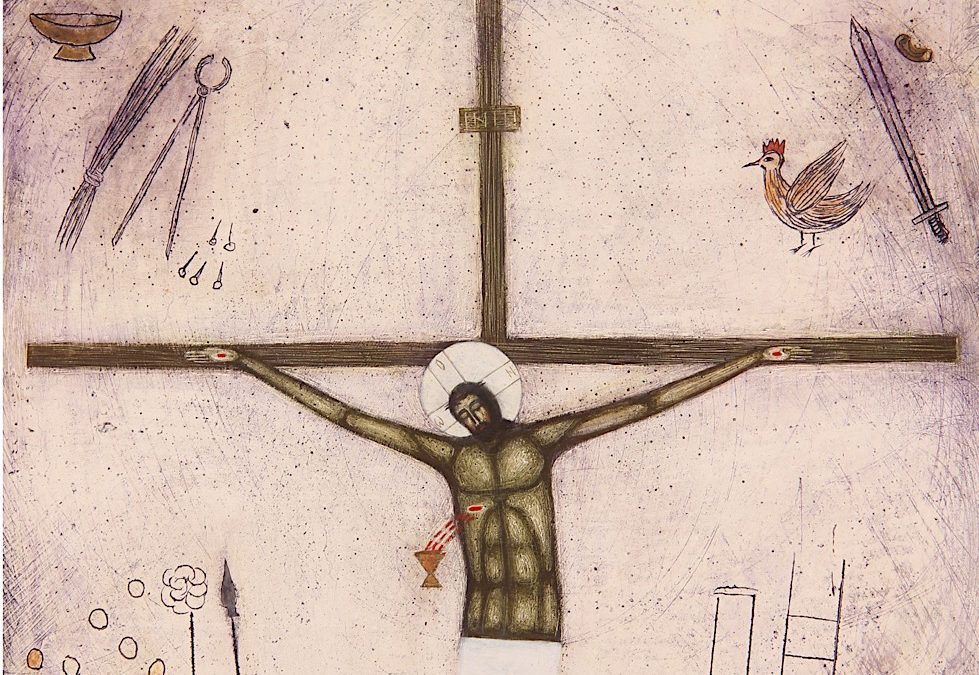

Sunrise that day:

Your own Creation displaying glory.

But no joy for You;

You stumbled, pain-wracked, through the story

To see it to its bitter end,

To see it through…

No hope, no friend

Could there attend You as You faced

What no one else could face:

The whole weight, reek, waste, and grief of the human race;

Sin itself put on You, the sinless One…

Father, Spirit, separated from suffering Son…

How did You persevere?

What kept You there – displayed, a broken thing,

As if You were NOT God? Not Lord? Not King?

What held You to that Cross through hours that lasted years –

Straining to contain the centuries’ mass of murders, lies, greed, fears?

Why did You choose to die one Friday afternoon –

You, Who created time itself?

Was there no other way

To wipe the slate clean, ransom all the slaves,

Than living every moment of that Hellish day

And then living Hell itself?

All, all for us – that we might truly say,

“My Savior” –

Pray,

“Our Father” –

Stay

With You, Immanuel,

Through all eternity …

I cannot see how we were worth Your agony.

But Your love declared it so

And You are the Truth

You are “I Am”

Logos. Lord.

Perfect,

slaughtered,

Lamb.

O Jesus, grant us sight today to see Your bleeding body

as Your gift

Of life to us,

the beggars that You lift

From muck and mire to holiness and peace.

O Jesus, give us breath to praise and faith to claim:

Your love

will

never

cease.

Shannon Vowell, a frequent contributor to Good News, blogs at shannonvowell.com. She is the author of Beginning Again: Discovering and Delighting in God’s Plan for Your Future available on Amazon. Art from Natalya Rusetska of Lviv, Ukraine. Special thanks to iconart-gallery.com

by Steve | Apr 14, 2022 | In the News

By George Mitrovich

Good News, May/June 2005

Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The presentation of the Gold Medal to Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, took place at a 90-minute ceremony on March 2, 2005, in the great rotunda of the United States Capitol.

Jackie Robinson was a Hall of Fame baseball player. But the Gold Medal isn’t given for athletic achievement – Robinson was a four-sports star at UCLA, and some believe baseball was not his best sport – but in recognition of one’s achievements as a human being.

In becoming the first black man to play in the major leagues, Robinson encountered racism in its vilest manifestations – racial taunts and slurs, insults on the playing field and off, character assassination, death threats, and anything else the wicked among us in mid-twentieth century America could throw at him. But despite the evil of such provocations he somehow found a way to rise above his tormentors, to literally turn the other cheek and demonstrate that however great his athletic skills, his qualities as a human being were infinitely greater.

When the time approached for Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Dodgers to sign Robinson, he had several difficult decisions to make. First, should he sign a black player? And if he did, what were the consequences? Second, did Robinson have the talent to play in the big leagues? Third, was he tough enough in the best sense to confront the certain racial turmoil he would face?

Rickey was a man of exceptional intelligence and ability. He was known throughout baseball as “the Mahatma” for his great wisdom (more than any other person he was responsible for creating baseball’s farm system, key factors in his success with the St. Louis Cardinals and later with the Dodgers in Brooklyn).

The assurance Rickey sought as to Robinson’s character was found in Jackie’s boyhood, growing up in Pasadena, California (he was born in Cairo, Georgia, the son of share croppers, and the grandson of slaves). In his youth Jackie came under the influence of a young minister in Pasadena. His name was Karl Everitt Downs, the 25-year old pastor at Scott Methodist Church where Jackie’s mother, Mallie, worshipped.

The story of Downs and Robinson is brilliantly told in Arnold Rampersad’s biography Jackie Robinson (Alfred A. Knopf, 1997).

Rampersad, dean of the humanities department at Stanford University, writes that Downs went looking for Robinson. He found a group of Jackie’s friends loitering on a street corner. He asked for Robinson, but no one answered. He left a message, “Tell him I want to see him at junior church.” Sometime later, Rampersad writes, “Jack delivered himself to the church and began a relationship that lasted only a few years, but changed the course of his life.”

Rampersad continues the story: “To Downs, Robinson evidently was someone special who had to be rescued from himself (Jackie had had some run-ins with the Pasadena police) and the traps of Jim Crow.” One of Jackie’s friends said, “I’m not sure what would have happened to Jack if he had never met Reverend Downs.”

“Downs led Jack back to Christ,” the author writes. “Under the minister’s influence, Jack not only returned to church, but also saw its true significance for the first time; he started to teach Sunday school. After punishing football games on Saturday, Jack admitted, he yearned to sleep late: ‘But no matter how terrible I felt, I had to get up. It was impossible to shirk duty when Karl Downs was involved. … Karl Downs had the ability to communicate with you spiritually,’ Jack declared, ‘and at the same time he was fun to be with. He participated with us in our sports. Most importantly, he knew how to listen. Often when I was deeply concerned about personal crises, I went to him.’

“Downs became a conduit through which Mallie’s message of religion and hope finally flowed into Jack’s consciousness and was fully accepted there. … Faith in God then began to register in him as both a mysterious force, beyond his comprehension, and as a pragmatic way to negotiate the world. A measure of emotional and spiritual poise such as he had never known at last entered his life.”

Robinson himself would say, “I had a lot of faith in God. … There’s nothing like faith in God to help a fellow who gets booted around once in a while.”

The influence of his mother, Mallie, and his pastor, Karl Downs, would forever affect the way Jackie Robinson lived his life, how he saw other people, and how he coped with discrimination. He had been taught that he was a child of God, and no one and no challenge, however brutal and dehumanizing, could take that away from him.

Why did Rickey find those experiences of the young Jackie so persuasive? Branch Rickey was also a Methodist. Not just a Methodist, but, according to Rampersad, “a dedicated, Bible-loving Christian who refused to attend games on Sunday.” His full name was Wesley Branch Rickey. He was a graduate of Ohio Wesleyan University – and the influence of the Methodist Church was a great factor in his life.

In Rampersad’s chapter on Jackie’s signing with the Dodgers – “A Monarch in the Negro Leagues (1944-1946)” – he tells the dramatic story of a meeting that took place in the late summer of 1945. The meeting was held on the fourth floor of an office building at 215 Montague Street in Brooklyn. In that meeting were Branch Rickey and a Dodger scout by the name of Clyde Sukeforth, who had been following Robinson with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues.

“Rickey made clear that Jack’s ability to run, throw, and hit was only one part of the challenge,” Rampersad wrote. “Could he stand up to the physical, verbal, and psychological abuse that was bound to come? ‘I know you’re a good ball player,’ Rickey barked. ‘What I don’t know is whether you have the guts?’

“Jack started to answer hotly in defense of his manhood, when Rickey explained, ‘I’m looking for a ball player with guts enough not to fight back.’

“Caught up now in the drama, Rickey stripped off his coat and enacted out a variety of parts that portrayed examples of an offended Jim Crow. Now he was a white hotel clerk rudely refusing Jack accommodations; now a supercilious white waiter in a restaurant; now a brutish railroad conductor, he became a foul-mouthed opponent, Jack recalled, talking about ‘my race, my parents, in language that was almost unendurable.’ Now he was a vengeful base runner, vindictive spikes flashing in the sun, sliding into Jack’s black flesh – ‘How do you like that, n—-r boy?’ At one point he swung his pudgy fist at Jack’s head. Above all, he insisted, Jack could not strike back. He could not explode in righteous indignation; only then would this experiment be likely to succeed, and other black men would follow in Robinson’s footsteps.

“Turning the other cheek, Rickey would have him remember, was not proverbial wisdom, but the law of the New Testament. As one Methodist believer to another, Rickey offered Jack an English translation of Giovanni Papini’s Life of Christ and pointed to a passage quoting the words of Jesus – what Papini called ‘the most stupefying of His revolutionary teachings’: ‘Ye have heard that it hath been said, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil: But whosoever shall smite thee on thy right check, turn to him the other also. And if a man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.’”

Many years later the Houston Chronicle told its readers a wonderful story about the two men fated to change baseball and race relations in America:

“Before Rickey’s death in 1965 at age 83, he sent a telegram to Robinson, who by that time was retired from baseball and involved in the Civil Rights movement with Martin Luther King Jr.

“Wheelchair bound and suffering from a heart condition, Rickey apologized to Robinson for not joining him at the march on Selma, Alabama.

“Robinson responded with a letter that read, in part: ‘Mr. Rickey, things have been very rewarding for me. But had it not been for you, nothing would be possible. Even though I don’t write to you much, you are always on my mind. We feel so very close to you and I am sure you know our love and admiration is sincere and dedicated. Please take care of yourself.’”

Through his on-the-field skills as a player and his off-the-field personal attributes, Jackie Robinson became an enduring symbol to black men and women across America – creating hope, raising their expectations, giving them faith that maybe, just maybe, the promise of American democracy that all men are created equal might become something more than words on a historic document. Eloquent words, yes; lovely words, yes; ennobling words, yes; but absent their reality that in the everyday lives of black Americans, they would remain that and nothing more – mere words.

And thus the presentation of the Gold Medal was given to remind all Americans of the significance of Jackie Robinson, to affirm his place as an individual who changed, not just a sport, the game of baseball, but more importantly the social and political dynamic of our nation’s life – and change it for the better. Indeed, with the exception of Martin Luther King Jr., Jackie Robinson was probably the most important black man in twentieth century America.

No one has made this point more convincingly than Buck O’Neil, chairman of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. O’Neil, whose own story as a black player has brought him national acclaim – he was the star of Ken Burns’ award winning baseball series on PBS – has pointed out that before President Truman desegregated the military, before the bus boycott in Birmingham, before the civil rights marches in the South, before Rosa Parks, before Brown v. Board of Education, and before anyone had ever heard of Martin Luther King Jr., there was Jackie Robinson.

Dr. King himself eloquently said of Jackie, “Back in the days when integration wasn’t fashionable, he understood the trauma and humiliation and the loneliness which comes with being a pilgrim walking the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.”

“The word for Jackie Robinson is ‘unconquerable,’” Red Smith, the great sports writer would say. “He would not be defeated. Not by the other team and not by life.”

The first Congressional Gold Medal was given to George Washington. Now one belongs to Jackie Robinson. One of these men was the father of our country, the other an athlete who tore down signs that read, “Whites only.” You can’t explain our history as a nation without understanding something about George Washington; neither can you explain it now without understanding something about Jackie Robinson. In a land that strives to exemplify both freedom and equality, they are forever bound as equals – recipients of the Congressional Gold Medal.

Thirty-three years after Jackie died, the Gold Medal ceremony took place in the Capitol of the United States; in a place some have called, “The Cathedral of Democracy.” It was a lovely day for America. The dream lives on.

George Mitrovich (1935-2019) was a frequent contributor to Good News, a lifelong member of First United Methodist Church in San Diego, and active in Wesleyan renewal efforts. He was president of The City Club of San Diego and The Denver Forum, two leading American public forums. For more than two years he played a key role in working with the Boston Red Sox, Congress, and the White House to obtain for Jackie Robinson the Congressional Gold Medal. The Family of Jackie Robinson has thanked him for his efforts and for having initiated the process that led to the presentation of the honor. This article first appeared in the May/June 2005 issue of Good News.

by Steve | Apr 14, 2022 | In the News

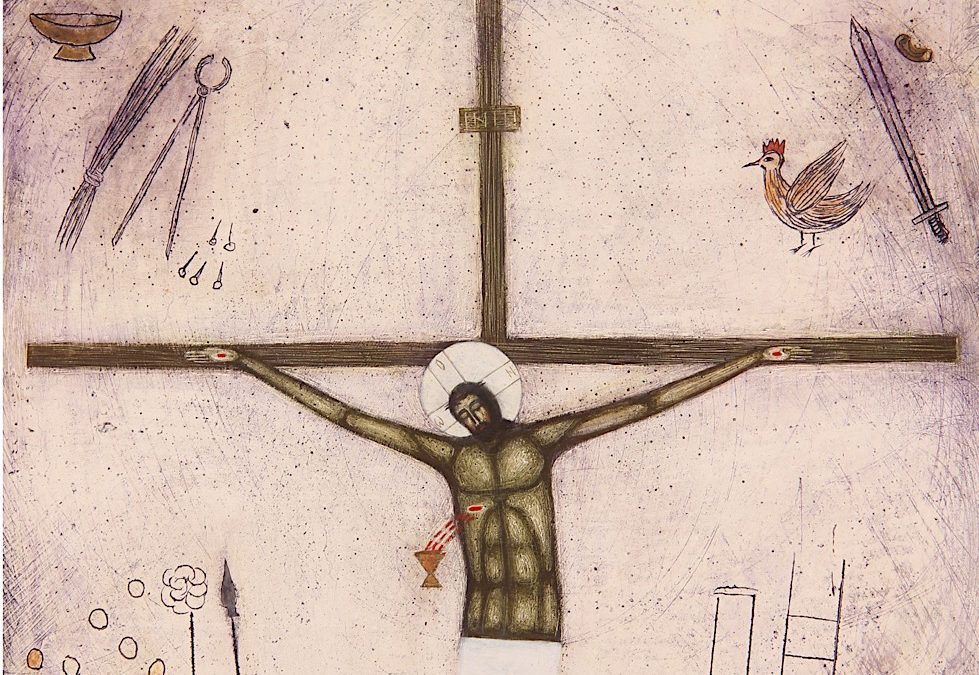

By Steve Beard

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.

“On a hill far away, stood an old rugged cross,” we sang. “The emblem of suffering and shame / And I love that old cross where the Dearest and Best / For a world of lost sinners was slain.”

Modern day hipsters may roll their eyes at the sentimental lyrics, but they stuck with me. It was a sing-a-long song about the most brutal injustice in human history and it became a well-known gospel chorus for an entire generation. Johnny Cash recorded four different versions. It was also recorded by Al Green, Ella Fitzgerald, Merle Haggard, Mahalia Jackson, Patsy Cline, Willie Nelson, and Loretta Lynn.

“The Old Rugged Cross” was written in 1913 by a Methodist preacher named George Bennard (1873-1958) who was converted to faith as a young man after walking five miles to a Salvation Army meeting. At age 15, he had lost his father in a mining accident. Bennard found new life and inspiration in giving his heart to a Savior riddled with nail scars who had conquered death.

“The crucifixion is the touchstone of Christian authenticity, the unique feature by which everything else, including the resurrection, is given its true significance,” writes the Rev. Fleming Rutledge in her magisterial book, The Crucifixion. “Without the cross at the center of the Christian proclamation, the Jesus story can be treated as just another story about a charismatic spiritual figure. It is the crucifixion that marks out Christianity as something definitively different in the history of religion. It is in the crucifixion that the nature of God is truly revealed. Since the resurrection is God’s mighty trans-historical “Yes” to the historically crucified Son, we can assert that the crucifixion is the most important historical event that has ever happened.”

When my father would serve communion at our United Methodist church, he said: “The body of Christ, broken for you. Feed on him in your heart by faith with thanksgiving.” Those words can still bring tears to my eyes. Sundays come and Sundays go, but those words stick in my soul. The Lamb of God was betrayed by a sleazy friend, ambushed by a well-armed battalion, falsely accused by conniving religious leaders, condemned by a spineless politician, and publicly executed before his weeping mother as cries of ridicule filled the air and birds of prey circled overhead.

To the abused who feels shame, this Crucified Christ stands with empathy. To the wrongly accused, this Crucified Christ stands with the truth. To all those victimized by injustice, this Crucified Christ stands with the innocent. “Come to me, all you who are weary … and I will give you rest,” Jesus said.

There are countless examples of contemporary Christian leaders who fail to live up to the Jesus ideal. Unfortunately, that has been the failed track record of Church history. But the Christ who was humiliated and shivved in the side on Golgotha is the genuine article. I try to keep my eyes on him. In every conceivable way, Jesus is counterintuitive. Who would have ever come up with a game plan of forgiving your enemies, turning the other cheek, and loving those who plot your demise?

“Even the excruciating pain could not silence his repeated entreaties: ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’ The soldiers gambled for his clothes,” wrote the late Anglican scholar, the Rev. Dr. John R.W. Stott. “Meanwhile, the rulers sneered at him, shouting: ‘He saved others, but he can’t save himself!’ Their words, spoken as an insult, were the literal truth. He could not save himself and others simultaneously. He chose to sacrifice himself in order to save the world.”

I understand the reluctance to spend inordinate time dwelling on the sufferings of Christ. It’s macabre and grotesque. It is the stigma of the story, the stain, the moment you turn your head away. But it is an inescapable part of redemption’s drama.

For those in the modern era, it is hard to imagine a time when crosses weren’t sold as bedazzled necklaces, home décor accessories, or garish t-shirt designs (“Body Piercing Saved My Life”). The cross was not always viewed as an icon for a faith dedicated to a kingdom that was not of this world.

“To the early Christians it was a symbol of disgrace. They could not look upon it as an object of reverence,” wrote historian George Willard Benson. “Death by crucifixion was the most shameful and ignominious that could be devised. That Christ should have been put to death, as were debased and despised criminals, was bitterly humiliating to his followers.”

Over the centuries since Christ’s blood-soaked public execution, the cross was slowly transformed from a symbol of shame and humiliation to one of victory and triumph for all of us who have been shamed and humiliated.

In his critically acclaimed book, Dominion: How The Christian Revolution Remade the World, British scholar Tom Holland points out that the tales of a human-divine hybrid were not unfamiliar in ancient history. Mythology from Egypt and Greece and Rome featured heroic monster-slayers and a pantheon of warlords that claimed to be empowered from the heavens.

“Divinity, then, was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings,” writes Holland. “Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque.”

The gospel is upside-down storytelling. Perhaps it helps explain the inexplicable allure of Jesus. The story does not end on a towering cross on the edge of town where the dying moan and mothers weep. More was to unfold.

Osiris, Zeus, and Odin are worshipped no longer. The Savior of the widow and orphan and tax collector is still worshipped around the globe. That is not chest-puffing triumphalism; it is simple reality.

“The crucifixion of Jesus, to all those many millions who worship him as the Son of the Lord God, the Creator of heaven and earth, was not merely an event in history, but the very pivot around which the cosmos turns,” writes Holland.

Holland only returned to the church of his childhood while writing his book. His thinking was dramatically affected while filming near a battlefront in an Iraqi town where Islamic State fighters had previously used crucifixion as a means of terror. “For the first time, I was facing the reality of crucifixion as it had been practiced by the Romans, face to face,” he told the Church Times. “It was physical in the air … people had been crucified by people who wanted the effect of crucifixions to be that which the Romans had wanted. They wanted to generate the sense of dread and terror and intimidation deep in the gut, and I felt that….

“I realized how important it was to me to believe that, in some way, someone being tortured on the cross illustrated the truth of the possibility that power might be vanquished by powerlessness, and that the weak might vanquish the strong, and that … hope might be found in the teeth of life in despair.”

Perhaps the hope found in the horror of the cross of Christ is the “assertion that the same God who made the world lived in the world and passed through the grave and gate of death,” wrote novelist Dorothy Sayer. Explain that to an unbeliever, and “they may not believe it; but at least they may realize that here is something that a man might be glad to believe.”

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. This article originally appeared in Good News in 2020. Artwork: “Station of the Cross: Fall” by Ostap Lozynsky of Lviv, Ukraine. Special thanks to iconart-gallery.com.

by Steve | Mar 18, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

The third postponement of General Conference until 2024 and the announced launch of the Global Methodist Church on May 1, 2022, have set off a storm of interest and controversy. Faced with the reality that a new denomination is moving forward without the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation, many questions answered by the Protocol are now uncertain.

Some individuals and churches are almost in panic mode, thinking that they have to make a decision right now (or at least by May 1). Others are just waking up to the fact that separation is taking place in the UM Church.

Important Timeline Considerations

First, it is important to understand that the launching of the Global Methodist Church on May 1 is just the starting point for that new denomination, not a deadline. Beginning May 1, the GM Church will be able to receive congregations, clergy, and annual conferences into its membership. There is no deadline for a congregation, clergy person, or annual conference to join the GM Church. It will be open to receiving members and churches from other denominations whenever they want to join, with no endpoint.

There are some local churches that have already withdrawn from the UM Church that will be positioned to join the GM Church on May 1. There may also be non-UM churches of a Wesleyan heritage who are also able to join on May 1. The vast majority of churches will take time over the next few years to move into the GM Church.

We understand that there are probably more than 100 churches across the U.S. that have already requested disaffiliation so far in 2022. These churches have been moving through a disaffiliation process guided by ¶ 2553 in the Discipline that requires apportionment and pension liability payments. These churches will need to have their disaffiliation approved by their annual conference meeting in May or June. They will not move into the GM Church until they receive that annual conference approval.

Now that the door is open to join the GM Church after May 1, there will be hundreds more local churches that will apply for disaffiliation over the next year. They will also have to move through the disaffiliation process set by their annual conference and bishop. This will again require approval by their annual conference, either at a special session called sometime near the end of 2022 or at their regular session in spring of 2023 (for the U.S. – the time frame for churches outside the U.S. may be different). Thus, this wave of churches would not be able to join the GM Church until the end of 2022 or the middle of 2023.

Then, as things develop for the GM Church and the UM Church has a chance to further define itself, there will be other congregations down the road that make the decision to move into the GM Church. It is important to note that the provisions of ¶ 2553 expire at the end of 2023, meaning that churches withdrawing under that paragraph need to do so before their annual conference session in 2023. However, there are other avenues in the Discipline that allow local churches to move to the GM Church (see below).

The bottom line is that there is no need to panic or make a rushed decision. Churches can take the time they need to evaluate their situation and the options available to them and make a prayerful, well-considered decision about their future. The doorway into the GM Church will always be open!

¶ 2553 Vs. ¶ 2548.2

There are two main ways that churches can disaffiliate from the UM Church and move into the GM Church: ¶ 2553 that was adopted at the 2019 special General Conference and ¶ 2548.2 that has been in the Discipline since 1948. What is the difference between the two?

¶ 2553 was adopted in 2019 as a way for churches that disagree with the denomination’s position on LGBT ordination or same-sex marriage (or with their annual conference’s response to the denomination’s position) to withdraw from the UM Church. The focus here is on withdrawing to become an independent congregation, after which the church might decide to align with a different denomination, such as the GM Church. Almost all the churches that have withdrawn under ¶ 2553 have become independent and not aligned with another denomination (so far).

¶ 2553 requires that the departing congregation pay two years’ apportionments and the total amount of its unfunded pension liability to the annual conference before departing. Approval for withdrawal requires a two-thirds vote of the church members voting at a church conference, the conference board of trustees, and a majority vote of the annual conference. The local church would then be able to keep its property, assets, and liabilities as it continues forward as an independent congregation or decides to align with another denomination.

¶ 2548.2 was originally adopted in 1948 to facilitate the transfer to other denominations of church facilities that no longer were able to serve a changing community by remaining United Methodist. The paragraph allows the annual conference to transfer (“deed”) the church’s property to a denomination represented in the Pan-Methodist Commission (five African-American Methodist denominations) or “another evangelical denomination.” Instead of moving into an independent status, the congregation would move from the UM Church directly into the GM Church.

¶ 2548.2 does not require specific monetary payments. Other paragraphs in the Discipline require the congregation’s share of unfunded pension liabilities be cared for. Wespath has expressed openness to these liabilities being covered by a promissory note secured by a lien on the church’s assets, rather than an upfront payment in full (see below). This approach would relieve one of the major financial barriers to especially smaller local churches wanting to move to the GM Church, but it requires annual conference approval of this approach. ¶ 2548.2 does not specify a threshold for local church approval of this transfer, so it could allow a simple majority vote by the church’s members. The transfer requires approval by the bishop, the district superintendents, the district board of church location and building, and the annual conference. The local church’s property, assets, and liabilities would be transferred to the GM Church, which would then release them to the local congregation because the GM Church has no trust clause.

Some annual conferences have put additional requirements on the disaffiliation process under ¶ 2553 (and could under ¶ 2548.2), such as an extended discernment period for the local church or payment of a percentage of the church’s property value. Some annual conferences at their upcoming sessions will be considering proposed policies that would govern the terms of local church disaffiliation under ¶¶ 2553 or 2548.2.

In the interest for an amicable resolution of our denominational division, the use of a promissory note for pension liabilities and the elimination of extra financial terms (additional apportionments, percentage of property value) would help by not placing undue hurdles in the way of local churches that want to move to the GM Church. With a vision for maintaining a heart of peace, it should be as easy and fair as possible for churches to move to where they want to be. Congregations should not feel as though they are being coerced into remaining United Methodist.

What about Pension liability?

In my Perspective two weeks ago, I wrote, “[¶ 2548.2] allows pension liabilities to be transferred to the local church or to the other evangelical denomination.” In another place, I stated, “a local church can carry its pension liability with it” into the GM Church. I need to clarify those statements, and in one respect, I was incorrect.

There are two ways that a church’s share of its annual conference’s unfunded pension liability (an amount roughly 4-7 times their annual apportionment) could be cared for. One way is an upfront cash payment by the church to the annual conference. Churches either would have to raise the money to make the payment or, in some instances, may be able to borrow that money as secured by their property.

The other way to care for the pension liability would be for the church to enter into a promissory note in the amount of the liability, secured by a lien on the church’s property. There would only be payments on that note if the annual conference needed to make payments to Wespath to cover unfunded liabilities. (This would normally only happen in case of a severe economic downturn.) The advantage of this approach is there would be no large upfront payment that could price many churches out of the possibility of withdrawing. Payments would only be made when there was a need for the money to cover pensions, which happens very rarely. The annual conference, as the pension plan sponsor, would need to approve this approach.

The UM annual conference would still have the pension liability, and the withdrawing local church’s share of that pension liability would still be owed to the UM annual conference. But with the promissory note approach, the church would only pay money to the annual conference when it is needed. In a recent FAQ document, Wespath allowed this approach. “While paragraph 1504.23 mandates a pension withdrawal payment, it does not address the timing of the payment under all potential paths of separation…. [U]nder paragraph 2548.2, while the payment is due in full, the annual conference in its sole discretion, may agree to adjust the timing of the payment.”

As currently envisioned, the Global Methodist Church would not assume any responsibility for unfunded pension liability. It would attach only to each local church, which would only make payments when the funds are needed. (I apologize for this incorrect information.)

As people process the options available to them, we will be dealing with many more questions that arise. There is no reason to have all the answers immediately. Take the time to research the answers. View the Global Methodist Church website for much information (globalmethodist.org).

See these two recent articles:

The process for Congregations to join the Global Methodist Church

How clergy align with the Global Methodist Church

More articles from the GM Church will be forthcoming. Feel free to email us with your questions. Stay tuned for more informative articles in the future.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo from Shutterstock.