By George Mitrovich

Good News, May/June 2005

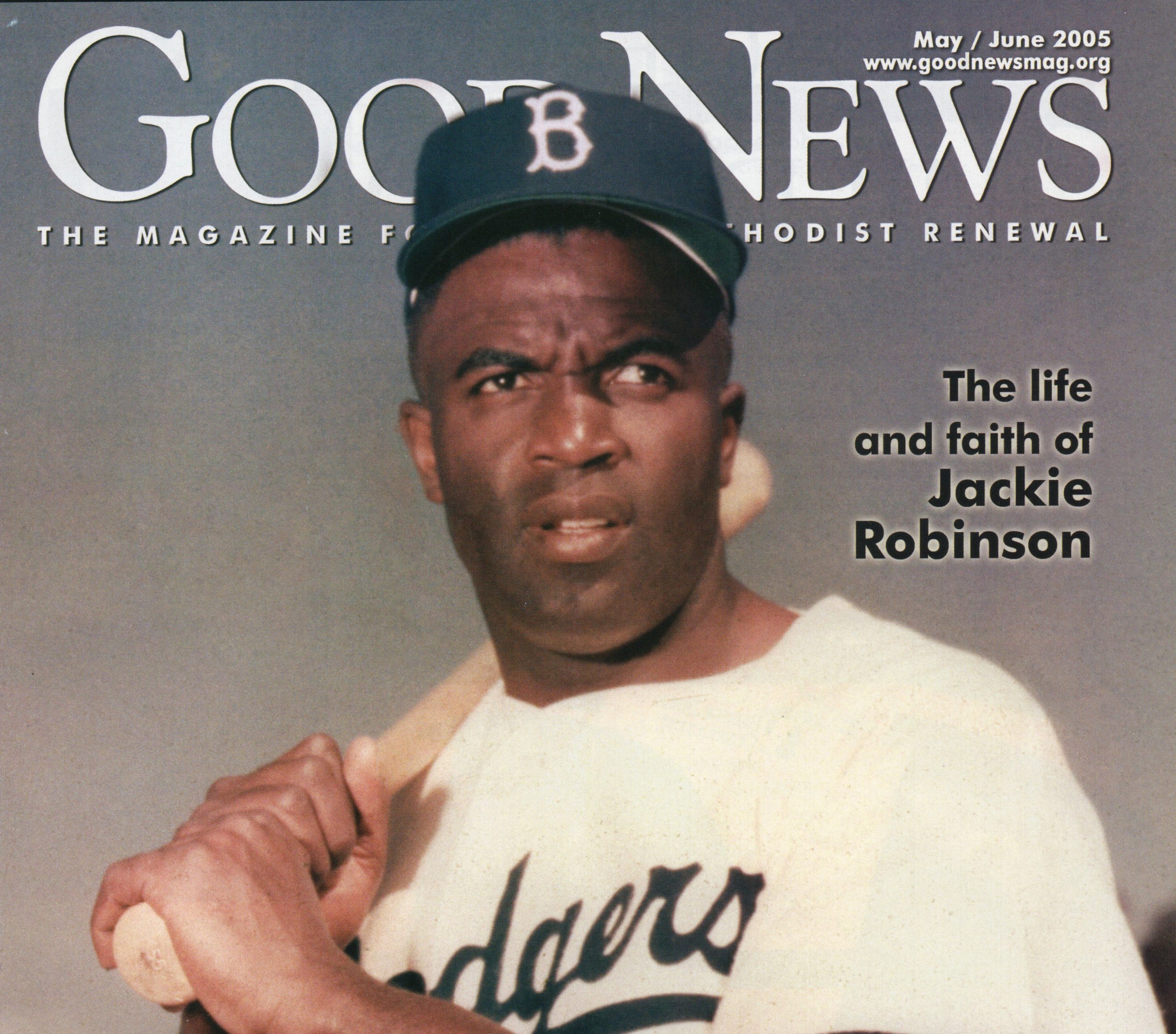

Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The presentation of the Gold Medal to Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, took place at a 90-minute ceremony on March 2, 2005, in the great rotunda of the United States Capitol.

Jackie Robinson was a Hall of Fame baseball player. But the Gold Medal isn’t given for athletic achievement – Robinson was a four-sports star at UCLA, and some believe baseball was not his best sport – but in recognition of one’s achievements as a human being.

In becoming the first black man to play in the major leagues, Robinson encountered racism in its vilest manifestations – racial taunts and slurs, insults on the playing field and off, character assassination, death threats, and anything else the wicked among us in mid-twentieth century America could throw at him. But despite the evil of such provocations he somehow found a way to rise above his tormentors, to literally turn the other cheek and demonstrate that however great his athletic skills, his qualities as a human being were infinitely greater.

When the time approached for Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Dodgers to sign Robinson, he had several difficult decisions to make. First, should he sign a black player? And if he did, what were the consequences? Second, did Robinson have the talent to play in the big leagues? Third, was he tough enough in the best sense to confront the certain racial turmoil he would face?

Rickey was a man of exceptional intelligence and ability. He was known throughout baseball as “the Mahatma” for his great wisdom (more than any other person he was responsible for creating baseball’s farm system, key factors in his success with the St. Louis Cardinals and later with the Dodgers in Brooklyn).

The assurance Rickey sought as to Robinson’s character was found in Jackie’s boyhood, growing up in Pasadena, California (he was born in Cairo, Georgia, the son of share croppers, and the grandson of slaves). In his youth Jackie came under the influence of a young minister in Pasadena. His name was Karl Everitt Downs, the 25-year old pastor at Scott Methodist Church where Jackie’s mother, Mallie, worshipped.

The story of Downs and Robinson is brilliantly told in Arnold Rampersad’s biography Jackie Robinson (Alfred A. Knopf, 1997).

Rampersad, dean of the humanities department at Stanford University, writes that Downs went looking for Robinson. He found a group of Jackie’s friends loitering on a street corner. He asked for Robinson, but no one answered. He left a message, “Tell him I want to see him at junior church.” Sometime later, Rampersad writes, “Jack delivered himself to the church and began a relationship that lasted only a few years, but changed the course of his life.”

Rampersad continues the story: “To Downs, Robinson evidently was someone special who had to be rescued from himself (Jackie had had some run-ins with the Pasadena police) and the traps of Jim Crow.” One of Jackie’s friends said, “I’m not sure what would have happened to Jack if he had never met Reverend Downs.”

“Downs led Jack back to Christ,” the author writes. “Under the minister’s influence, Jack not only returned to church, but also saw its true significance for the first time; he started to teach Sunday school. After punishing football games on Saturday, Jack admitted, he yearned to sleep late: ‘But no matter how terrible I felt, I had to get up. It was impossible to shirk duty when Karl Downs was involved. … Karl Downs had the ability to communicate with you spiritually,’ Jack declared, ‘and at the same time he was fun to be with. He participated with us in our sports. Most importantly, he knew how to listen. Often when I was deeply concerned about personal crises, I went to him.’

“Downs became a conduit through which Mallie’s message of religion and hope finally flowed into Jack’s consciousness and was fully accepted there. … Faith in God then began to register in him as both a mysterious force, beyond his comprehension, and as a pragmatic way to negotiate the world. A measure of emotional and spiritual poise such as he had never known at last entered his life.”

Robinson himself would say, “I had a lot of faith in God. … There’s nothing like faith in God to help a fellow who gets booted around once in a while.”

The influence of his mother, Mallie, and his pastor, Karl Downs, would forever affect the way Jackie Robinson lived his life, how he saw other people, and how he coped with discrimination. He had been taught that he was a child of God, and no one and no challenge, however brutal and dehumanizing, could take that away from him.

Why did Rickey find those experiences of the young Jackie so persuasive? Branch Rickey was also a Methodist. Not just a Methodist, but, according to Rampersad, “a dedicated, Bible-loving Christian who refused to attend games on Sunday.” His full name was Wesley Branch Rickey. He was a graduate of Ohio Wesleyan University – and the influence of the Methodist Church was a great factor in his life.

In Rampersad’s chapter on Jackie’s signing with the Dodgers – “A Monarch in the Negro Leagues (1944-1946)” – he tells the dramatic story of a meeting that took place in the late summer of 1945. The meeting was held on the fourth floor of an office building at 215 Montague Street in Brooklyn. In that meeting were Branch Rickey and a Dodger scout by the name of Clyde Sukeforth, who had been following Robinson with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues.

“Rickey made clear that Jack’s ability to run, throw, and hit was only one part of the challenge,” Rampersad wrote. “Could he stand up to the physical, verbal, and psychological abuse that was bound to come? ‘I know you’re a good ball player,’ Rickey barked. ‘What I don’t know is whether you have the guts?’

“Jack started to answer hotly in defense of his manhood, when Rickey explained, ‘I’m looking for a ball player with guts enough not to fight back.’

“Caught up now in the drama, Rickey stripped off his coat and enacted out a variety of parts that portrayed examples of an offended Jim Crow. Now he was a white hotel clerk rudely refusing Jack accommodations; now a supercilious white waiter in a restaurant; now a brutish railroad conductor, he became a foul-mouthed opponent, Jack recalled, talking about ‘my race, my parents, in language that was almost unendurable.’ Now he was a vengeful base runner, vindictive spikes flashing in the sun, sliding into Jack’s black flesh – ‘How do you like that, n—-r boy?’ At one point he swung his pudgy fist at Jack’s head. Above all, he insisted, Jack could not strike back. He could not explode in righteous indignation; only then would this experiment be likely to succeed, and other black men would follow in Robinson’s footsteps.

“Turning the other cheek, Rickey would have him remember, was not proverbial wisdom, but the law of the New Testament. As one Methodist believer to another, Rickey offered Jack an English translation of Giovanni Papini’s Life of Christ and pointed to a passage quoting the words of Jesus – what Papini called ‘the most stupefying of His revolutionary teachings’: ‘Ye have heard that it hath been said, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil: But whosoever shall smite thee on thy right check, turn to him the other also. And if a man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.’”

Many years later the Houston Chronicle told its readers a wonderful story about the two men fated to change baseball and race relations in America:

“Before Rickey’s death in 1965 at age 83, he sent a telegram to Robinson, who by that time was retired from baseball and involved in the Civil Rights movement with Martin Luther King Jr.

“Wheelchair bound and suffering from a heart condition, Rickey apologized to Robinson for not joining him at the march on Selma, Alabama.

“Robinson responded with a letter that read, in part: ‘Mr. Rickey, things have been very rewarding for me. But had it not been for you, nothing would be possible. Even though I don’t write to you much, you are always on my mind. We feel so very close to you and I am sure you know our love and admiration is sincere and dedicated. Please take care of yourself.’”

Through his on-the-field skills as a player and his off-the-field personal attributes, Jackie Robinson became an enduring symbol to black men and women across America – creating hope, raising their expectations, giving them faith that maybe, just maybe, the promise of American democracy that all men are created equal might become something more than words on a historic document. Eloquent words, yes; lovely words, yes; ennobling words, yes; but absent their reality that in the everyday lives of black Americans, they would remain that and nothing more – mere words.

And thus the presentation of the Gold Medal was given to remind all Americans of the significance of Jackie Robinson, to affirm his place as an individual who changed, not just a sport, the game of baseball, but more importantly the social and political dynamic of our nation’s life – and change it for the better. Indeed, with the exception of Martin Luther King Jr., Jackie Robinson was probably the most important black man in twentieth century America.

No one has made this point more convincingly than Buck O’Neil, chairman of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. O’Neil, whose own story as a black player has brought him national acclaim – he was the star of Ken Burns’ award winning baseball series on PBS – has pointed out that before President Truman desegregated the military, before the bus boycott in Birmingham, before the civil rights marches in the South, before Rosa Parks, before Brown v. Board of Education, and before anyone had ever heard of Martin Luther King Jr., there was Jackie Robinson.

Dr. King himself eloquently said of Jackie, “Back in the days when integration wasn’t fashionable, he understood the trauma and humiliation and the loneliness which comes with being a pilgrim walking the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.”

“The word for Jackie Robinson is ‘unconquerable,’” Red Smith, the great sports writer would say. “He would not be defeated. Not by the other team and not by life.”

The first Congressional Gold Medal was given to George Washington. Now one belongs to Jackie Robinson. One of these men was the father of our country, the other an athlete who tore down signs that read, “Whites only.” You can’t explain our history as a nation without understanding something about George Washington; neither can you explain it now without understanding something about Jackie Robinson. In a land that strives to exemplify both freedom and equality, they are forever bound as equals – recipients of the Congressional Gold Medal.

Thirty-three years after Jackie died, the Gold Medal ceremony took place in the Capitol of the United States; in a place some have called, “The Cathedral of Democracy.” It was a lovely day for America. The dream lives on.

George Mitrovich (1935-2019) was a frequent contributor to Good News, a lifelong member of First United Methodist Church in San Diego, and active in Wesleyan renewal efforts. He was president of The City Club of San Diego and The Denver Forum, two leading American public forums. For more than two years he played a key role in working with the Boston Red Sox, Congress, and the White House to obtain for Jackie Robinson the Congressional Gold Medal. The Family of Jackie Robinson has thanked him for his efforts and for having initiated the process that led to the presentation of the honor. This article first appeared in the May/June 2005 issue of Good News.

0 Comments