by Steve | Aug 4, 2023 | Front Page News, In the News

Centrists Describe Future UMC —

By Thomas Lambrecht —

The last two Perspectives (here and here) extrapolated what the future United Methodist Church might look like on the basis of a foundational article from Mainstream UMC (a centrist advocacy group within The United Methodist Church). A new Mainstream article this week goes further in describing how many centrists see the future of the UM Church.

The article is entitled, “Next Steps (1 of 3): Honesty.” True to its title, the article is honest about where centrists see the church today and where they believe it will go in the near future. This honesty is commendable and helps United Methodists across the spectrum understand what is at stake, as they make decisions about their alignment with the church. It should be remembered that centrists purport to represent the “broad center” of the church and hold most of the power positions in the bureaucracy and the Council of Bishops. Therefore, centrists are a key power bloc in determining the decisions made by the church. Below are some quotes from the article that tell us what we need to know about its vision for the future of the UM Church.

Current U.S. Church Identity

• “Many US and Western European churches and annual conferences are already meeting the ministry needs of their mission field by openly, unapologetically ordaining and marrying LGBTQ persons. … We do not buy into black-and-white dualistic understandings of human sexuality.”

This statement points to the reality that many U.S. annual conferences have moved beyond living by the Book of Discipline. They are disregarding its teachings on marriage and human sexuality. They are ordaining persons regardless of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or partnered status. Clergy who perform same-sex weddings are, for the most part, not experiencing any adverse consequences. Most U.S. and Western European annual conferences have adopted a theology that affirms LGBT relationships and practices.

“There is NO scenario where the US church changes this identity.” Regardless of what the Discipline says, much of the U.S. church has moved on in ignoring it. There will be no going back from this current situation in the U.S. church.

Centrists and the Bible

• “We believe in the primacy of Scriptures and prayerfully explore them through the lenses of Tradition, Reason, and Experience. We believe the Biblical views on slavery, women, polygamy, divorce, and homosexuality are descriptive Biblical truths, that describe what was true for others in another time and place. We believe in the prescriptive Biblical truths of justice, inclusion, and grace.”

Although stating a commitment to the primacy of Scripture, when it comes to issues of marriage and sexuality, many centrists in fact give primacy to experience and reason. There is no real doubt about the clear teaching of Scripture. But many have found a way to say Scriptural teachings don’t apply in this case. They would say, “Because our experience of sexuality and knowledge of sexuality is greater than and different from the biblical authors, we know better what God really wants us to do (namely, affirm same-sex relationships).”

Many centrists use a “canon within the canon” to determine what the Bible teaches. They focus on “justice, inclusion, and grace” (as they define them) to decide whether a particular biblical teaching is in or out. If a particular teaching is not just, inclusive, or gracious (again, as they define them), then that teaching is not applicable in today’s world. (In contrast, traditionalists believe we should strive to understand the “whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:27) with all its nuances, seeing the Bible as a whole and understanding how its various teachings and time periods fit together.)

The effect of this focus on justice and inclusion is a particular social-justice agenda for the church that may or may not reflect the actual teachings of Scripture. More significantly, it takes the church’s focus off of evangelism and discipleship and shifts it to the political sphere. Many centrists believe the church is accomplishing its mission when it advocates for particular political positions. While such advocacy may be needed at times, the overwhelmingly biblical emphasis is on evangelism, discipleship, and lovingly caring for others in practical ways. This has been the hallmark of evangelical and traditionalist Methodist churches for generations.

General Conference 2024

• “We, very likely, have the votes to remove the anti-gay language at General Conference 2024.”

This is a true statement. In the aftermath of the 2019 General Conference in St. Louis, delegate elections in the U.S. annual conference resulted in a more progressive delegation. By our calculations, the delegate count would have been very close in 2020, although still slightly favoring traditionalists. Since that time, however, almost 6,200 U.S. churches have disaffiliated, including a number of traditionalist delegates to General Conference. This year, many U.S. annual conferences elected replacement delegates for those who resigned or died since 2019, meaning the delegation will skew even more toward the progressive end. In addition, some annual conferences in Europe that would normally send traditionalist delegates have withdrawn from the UM Church.

• “If we do have a ‘compatibilist’ majority, there is NO scenario where, after suffering significant membership losses in the US, we do not vote to change the language at this upcoming General Conference.”

Many centrists view changing the church’s position on the marriage and ordination of gays and lesbians as an issue of the church’s survival. The allusion to “significant membership losses” indicates they believe that our current biblical stance on these issues is causing the membership losses. This makes centrists very motivated to change the church’s definition of marriage and allow ordination for partnered gays and lesbians. They think it is the only way the church will survive in the U.S.

This whole line of thinking is questionable. Not one of the other Mainline denominations saw their membership grow as a result of changing their position on marriage and sexuality. In fact, their membership losses (Episcopal, Presbyterian, Lutheran, northern Baptist, and United Church of Christ) only increased.

Regardless of whether centrist theories of church growth are correct, their statements indicate it is a near certainty that the definition of marriage and ordination standards will be changed at the 2024 General Conference in a progressive direction.

• “We do not yet have 2/3 for regionalization.”

This statement recognizes that the African delegates hold the key to whether regionalization takes place. African delegates make up about one-third of the delegates, so they could potentially block regionalization at the General Conference if they are not convinced it is the right thing to do. Even more importantly, African annual conferences make up over half of the annual conference members that need to vote by two-thirds to approve the regionalization constitutional amendments. Even if only two-thirds of African annual conference members vote against regionalization, they can defeat it.

The regionalization proposal is being marketed as coming from the central conferences outside the U.S. because some of the leaders behind the proposal are from the central conferences. However, the grass roots membership of the central conferences is not yet convinced to support regionalization. Therefore, its adoption at the 2024 General Conference (and subsequent ratification by the annual conferences) is questionable.

• “There is NO scenario where Africa would ordain LGBTQ pastors, even if the General Conference told them to. There is NO scenario where the United States will go back to trials and exclusion, even if the General Conference told them to.”

This statement points out the basic irrelevance of the General Conference. No matter what the General Conference decides, people will do what they think is right, even if it contradicts the General Conference.

Some U.S. bishops have been pushing to marginalize the power of the General Conference and weaken its authority. They believe the General Conference is inefficient and causes division in the church. They would rather the Council of Bishops and the general boards and agencies would run the church. Of course, this would disempower the voices of the grass roots of the church who elect the delegates and empower a favored elite to govern the church. It would also turn United Methodist governance on its head, as the General Conference has been given supreme authority over the church by the Book of Discipline. But again, no matter what the Discipline says, certain leaders think they know better how the church should be run than the voice of the people.

This quote also shows how committed to the LGBTQ agenda centrists are. As we saw in the aftermath of the 2019 General Conference, no matter what the General Conference decides, centrists and progressives will persist in their defiant actions. The possibility of any kind of Traditional Plan or maintaining accountability to a traditional, biblical view of marriage and sexuality is out of the question for the U.S. part of the UM Church.

Centrists and Africa

• “We are committed to remaining in relationship with Africa and the Philippines but recognize that they are much more traditional than even the US traditionalists. They may not be willing to stay in relationship with a church that is openly, unapologetically ordaining LGBTQ pastors … We need to be prepared to live with that … The US is ‘compatibilist’ and willing to live with regions that are much more conservative. The most traditional regions, Africa and the Philippines, then get to decide if they are willing to live with the US church. We cannot, however, live together under false pretenses.”

Although centrists say they are willing to live with regions that are much more conservative, there will continue to be efforts to persuade United Methodists outside the U.S. to support the LGBTQ agenda. Just as the U.S. government often lobbies African governments to change their laws about marriage and homosexuality, UM progressives and centrists will continue to lobby the central conferences to accept and eventually affirm LGBTQ persons and relationships.

Centrists represented by Mainstream UMC are prepared to acknowledge that more traditional parts of the church outside the U.S. may decide to separate. That is a significant acknowledgement. Let us hope that, rather than throw up roadblocks to traditionalists outside the U.S., centrists are prepared to allow them to make informed, prayerful discernment and will honor their decisions.

Currently, the Council of Bishops is saying that Par. 2553 does not apply outside the U.S., even though the language adopted by the 2019 General Conference plainly says, “This new paragraph became effective at the close of the 2019 General Conference.” The only other way for churches outside the U.S. to disaffiliate is through becoming an autonomous Methodist Church, a laborious process that requires General Conference and central conference approval.

Some bishops and other leaders have been advocating for churches to postpone their decision about disaffiliation until after the 2024 General Conference. They are saying that one never knows what the General Conference will decide until the votes are taken. While these leaders are technically correct, the Mainstream articles have given us a clearer understanding of what will happen at the General Conference and what the future UM Church will look like. We can predict the outcome with near certainty.

There will be proposals at the 2024 General Conference to allow local churches and annual conferences outside the U.S., as well as local churches in areas where U.S. annual conferences have imposed significant additional costs, to disaffiliate from the UM Church. Centrists can help facilitate their vision of the future UM Church by adopting these new exit paths. Let us put an end to the fighting and allow mature Christian adults to make their own prayerful discernment about their participation in the future UM Church. Mainstream UMC has given us a much clearer picture of what that future church will look like.

Thomas Lambrecht is United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News. Image: Delegates and bishops join in prayer at the front of the stage before a key vote on church policies about homosexuality during the 2019 United Methodist General Conference in St. Louis. Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

by Steve | Jul 28, 2023 | In the News, Perspective / News

What the Regionalization Agenda Tells Us about the Future of the UMC, Part 2 —

By Thomas Lambrecht —

In last week’s Perspective, I surveyed a recent article by Mainstream UMC (a centrist advocacy group within The United Methodist Church) outlining the case for the regionalization of the church. This important article advocates for a plan that would set the UM Church in the U.S. as its own regional conference, with wide latitude to “adapt” the Book of Discipline according to the views of U.S. delegates and different from how other regions of the church might position themselves.

Continuing our survey in today’s Perspective, the article gives some hints as to the bigger picture implications of moving forward with the regionalization plan and the conception of the UM Church envisioned by many centrists.

Addressing a Global “Divide”

The Mainstream article portrays the 2019 “Traditional Plan” as being “imposed” upon the church, primarily by delegates from outside the U.S. and especially in Africa. It states, “60 percent of the votes to impose the Traditional Plan on the U.S. church were cast by international delegates. In fact, 80 percent of all non-U.S. delegates and 90 percent of all African delegates voted against two-thirds of the U.S. church on a policy that only affects the practice of ministry in the United States.”

The article presumably makes this claim because it was primarily the U.S. delegates who were agitating to change the denomination’s position and institute the “One Church Plan” that would have allowed same-sex weddings and ordaining partnered gays and lesbians. However, even this portrayal is inaccurate because Germany, Denmark, Norway, and some other Europeans, as well as some in the Philippines favored a change in the church’s policies.

More importantly, this characterization misrepresents the church’s decision-making process. While the “Traditional Plan” is congruent with most African culture, not all African countries outlaw homosexuality. Notably, South Africa has adopted a permissive attitude toward LGBT relationships. Some other countries do not have laws criminalizing same-sex relationships. So the “Traditional Plan” applies just as much to the African church as to the U.S. church.

Furthermore, if the UM Church is truly to be a global church, it must respect the voices of all parts of the global church community. If all are not agreed, how can we walk together (Amos 3:3)? Rather than the African delegates seeking to impose the “Traditional Plan” on the U.S., the Council of Bishops and progressive/centrist UM leaders attempted to impose the “One Church Plan” on the African church. African, European, Filipino, and U.S. traditionalists were not willing to agree to the “One Church Plan.” By their words and actions since 2019, most bishops and progressive/centrist UM leaders have continued to try to impose the “One Church Plan” on the church. They would not take “no” for an answer.

There is no question that there is a global “divide” over these questions. The problem is how to resolve that divide. Progressives/centrists are unwilling to accept the “Traditional Plan.” Most traditionalists, including those in Africa, Europe, and the Philippines, are unwilling to accept the “One Church Plan.” The divide is not geographical, but theological.

Given that neither party is willing to accept the other’s way forward, it seemed that separation was the only viable way to resolve the divide. However, most bishops and many other UM leaders have bent over backwards to prevent separation from occurring outside the U.S., as well as in some conferences in the U.S.

They want to impose “unity” and the “One Church Plan” by making it impossible to disaffiliate. Now they want to impose regionalization as the way to implement the “One Church Plan.”

The Mainstream article seems to envision a future UM Church where it is acceptable to impose a solution on parts of the church that disagree with it, as long as it is the “right” solution. Traditionalists have been willing to make substantial sacrifices in order to resolve the divide through separation. Many progressives/centrists have instead imposed barriers outside the U.S. and in some parts of the U.S. in order to impose the “right” (“One Church Plan/Regionalization”) solution to the divide. Which is more respectful of the consciences and voices of church members and leaders?

Is UM Governance “Undemocratic?”

The Mainstream article makes the claim that the United Methodist system is “quirky” and “not very democratic.” Many centrists envision a need to change the system, but are unclear how they would change it.

Complaints center around several points:

- Almost all voting at General Conference is done by secret ballot (electronic voting).

- In some cultures, particularly in Africa, delegates tend to vote as a block, meaning that some annual conferences vote nearly unanimously for or against particular proposals.

- Lobbying by Good News and other traditionalist groups over the years has somehow distorted democracy in an effort to “prop up the views of a shrinking minority of conservative delegates in the United States.”

The article acknowledges that secret ballot voting in the past has been seen as “help[ing] advance social justice issues in the church.” But now that the General Conference has passed legislation objectionable to progressives and centrists, secret ballots are a problem. It seems the only real reason to do away with secret ballots is to open the delegates to being pressured to vote in line with a centrist/progressive agenda.

The theory of electing General Conference delegates is that they are elected to act according to their best prayerful wisdom. They are trusted to be representative of the opinions of their annual conference. But they are delegated authority to act according to their own conscience (which is why they are called “delegates”). Doing away with secret ballot voting would open a can of worms allowing the kind of pressure politics seen in the secular world to invade the church. It would also favor the promotion of a politically correct agenda via shame and intimidation. That is not how our church should conduct its business.

It is true that some cultures, particularly in Africa, value community solidarity higher than individual opinions. At times, this can result in unhealthy block voting. But on the issues that the Mainstream article focuses on, African delegates are nearly unanimous in their opposition to allowing same-sex marriage and ordination in the church. To decry block voting is to deny that Africans can agree on a particular topic and all vote with a similar mind. It is also to disrespect a culture that manifests different values and priorities than American ones. The article gives no mechanism for doing away with block voting. Again, it seems to want to resort to shame and intimidation to force delegates not to vote in the same way with each other.

Lobbying by caucuses and interest groups within the UM Church is not a new phenomenon. Even the official boards and agencies of the church lobby the delegates. They host meals and briefings to persuade delegates to support agency initiatives and budgets. The Methodist Federation for Social Action has been around since 1907 lobbying for liberal and progressive causes within the church. Lobbying and persuasion are part of the very fabric of democracy. Just because some progressives and centrists do not like the causes that traditionalists lobby for does not mean that all lobbying ought to be ended. Nor is it justification for excluding only traditionalist lobbying, while allowing centrist and progressive lobbying. It is those actions that would be antidemocratic, not lobbying itself.

Follow the Money

Lastly, the Mainstream article critiques the fact that the U.S. part of the church contributes 99 percent of the money to support the functioning of the denomination, but it may in the future have less than 50 percent of the votes. The article asks, “the U.S. church is willing to fund mission and ministry around the world, but why should it fund a governance structure that is actively harming the remaining 80 percent of U.S. churches?”

This is a real issue that any global denomination needs to address. There is financial power for those who have resources. There is political power for those who have votes. But when the financial and political power do not line up, it can cause division in the body.

Part of the solution is for the churches in Africa and the Philippines to become less financially dependent upon the U.S. and Europe. Long-term, the goal needs to be for each part of the church to become financially self-sufficient or self-supporting in its own context. The sharing of financial resources from the U.S. and Europe ought to be tailored to empowering churches in less developed countries, rather than on keeping them dependent.

But it would be unfortunate for the U.S. church to use its financial resources to leverage political power away from the churches outside the U.S. The fact that the U.S. possesses the bulk of the financial resources of the denomination should not give the U.S. the ability to do whatever it wants without the input and agreement of the rest of the church. Otherwise, the church would return to seeing itself with a colonial mentality of a U.S. church with mission outposts overseas.

In a healthy marriage the husband and wife may contribute unequally to the financial resources of the family, but the couple still sees their financial resources as belonging to the couple, rather than to each individually. The same should be true in the church. The financial and non-financial resources of each part of a global church belong to the whole church, not each part separately.

At the same time, the churches outside the U.S. will need to face the reality that the U.S. church will have diminished financial resources to share with the rest of the world. While the U.S. church may have lost over 20 percent of its congregations, the General Council on Finance and Administration believes ultimately the church will see a 40 percent drop in income for the general church. That is reflected in the budget proposed to the 2024 General Conference. After the cash windfall of disaffiliation fees is expended, the U.S. church will not be able to support churches outside the U.S. at the same level as before.

The shifting availability of financial resources and the shift in membership will cause change to happen in the UM denomination. That change could bring about a healthier relationship between financial power and political power, or it could cause a deepening divide between the U.S. church and the financially poorer parts of the church outside the U.S. Using the shift in financial resources as a reason to adopt regionalization could lead to a deepening divide.

Where will this lead?

The Mainstream article states, “Our entire global governance/administrative/ financial structure must change. … the current apparatus is an outdated relic of Western colonialism and is irreparably broken.” The question is what kind of change will happen.

The proposed answer of regionalization only tends to cause further separation between the UM churches in the various parts of the globe. It continues to reflect and enable a U.S. church mainly interested in preserving its own autonomy and self-governance, at the expense of global connection and interrelatedness. The mindset behind many progressive and centrist proponents of regionalization is to create a system where they can ensure that the church makes the “right” decisions and adopts the “right” positions, even if that means disregarding the voices of those outside the U.S. who might disagree. Such an approach would unfortunately trade one sort of colonialism for another.

One wonders why, if having churches outside the U.S. with enough power to thwart the wishes of American progressives and centrists is such a problem, would not the church be better off going the whole way and allowing separation for those who desire it outside the U.S.? Why the intense desire to hang on to churches outside the U.S. that pose such a threat to the U.S. that they must be disenfranchised through a regionalized governance? Let those who agree walk together, and those who disagree walk separately. Anything else ends up being an attempt to impose the will of one part of the church on another part. We have seen how that movie ends.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Jul 25, 2023 | In the News, Perspective / News

What the Regionalization Agenda Tells Us about the Future of the UMC, Part 1 —

By Thomas Lambrecht —

In a recent article, Mainstream UMC (a centrist advocacy group within The United Methodist Church) outlines the case for the regionalization of the church. They consider the article important, calling it “an important baseline and reference point for where we are as a church.” It advocates for a plan that would set the UM Church in the U.S. as its own regional conference, with wide latitude to “adapt” the Book of Discipline according to the views of U.S. delegates and different from how other regions of the church might position themselves.

The most prominent issue motivating the push toward regionalization is differences over the definition of marriage and the ordination of practicing LGBT persons. Regionalization would allow the U.S. and Western Europe to adopt one definition of marriage that would allow same-sex marriage and the ordination of partnered LGBT persons, while Africa and Eastern Europe could maintain the current definition of marriage as between one man and one woman, while continuing to refuse ordination to practicing gays and lesbians. This strategy is seen by some as an attempt to allow the U.S. to have its own way on these issues, while keeping Africa in the United Methodist fold.

Going beyond the individual issues, however, the article’s rhetoric gives some hints as to the bigger picture implications of moving forward with the regionalization plan.

Culture Vs. Scripture

The Mainstream UMC article frames the regionalization proposal as a way to accommodate differences in culture. The article speaks of the ability “to adapt portions of the rules to fit their cultural contexts.” It goes on to say, “If the structure does not change, cultural values will continue to be imposed upon one region of the world by another.” In fact, the word “culture” or “cultural” appears seven times in the article.

Mainstream UMC apparently sees the definition of marriage as a cultural issue. The main reason for adopting a non-traditional view of marriage given in the piece is because, according to the Pew Research Center, “back in 2014 60 percent of U.S. Methodists supported same-sex marriage. They note that ‘Americans’ views about homosexuality have shifted further since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2015 decision to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide.’”

Most traditionalists, however, see the definition of marriage as a moral and Scriptural issue. Jesus defines marriage in Matthew 19:4-6, quoting Genesis 2:24). Throughout Scripture, marriage is defined as between male and female, and the New Testament clarifies that marriage ought to be monogamous, not polygamous.

The larger implication from this difference of perspective is that the future UM Church is more likely to adapt to the surrounding culture than live differently, no matter what Scripture says. It appears the church may take its cues on moral decisions from what is culturally acceptable, rather than from what the Bible teaches.

This is a dangerous approach to setting moral standards of behavior. Scripture repeatedly urges us not to go along with what a godless world does but to stand against it to live the Jesus way. “Don’t copy the behavior and customs of this world, but let God transform you into a new person by changing the way you think” (Romans 12:2). “So, you must live as God’s obedient children. Don’t slip back into your old ways of living to satisfy your own desires” (I Peter 1:14). “Live clean, innocent lives as children of God, shining like bright lights in a world full of crooked and perverse people” (Philippians 2:15).

Backtracking on Being a Global Church?

The article makes the astounding claim that The United Methodist Church is “not really a global church.” The article says that United Methodists make up “only about 30 percent of all Methodists in the world and just above 50 percent of the Methodist family in the US.” Apparently in Mainstream’s view, because United Methodism does not make up the vast majority of global Methodists, it is not a global church, despite the fact that it has congregations on four continents and dozens of countries.

What Mainstream is arguing is that United Methodism is governed in a different way from many other Methodist bodies in the world. Most other Methodist denominations are country-based or allow the church in each country to be at least somewhat autonomous, governing its own affairs. Uniquely, United Methodism over the years has striven to be a truly global church, where Methodists from many different countries determine together how they will live out the Christian faith.

Now, Mainstream apparently wants to backtrack on that unique commitment. It wants to let each part of the UM Church govern itself, with much less connection and foreclosing the influence of other parts of the global church. Coincidentally, this push for regional autonomy comes at a time when the church in Africa is poised to exercise greater influence on the direction of the UM Church. While the U.S. was in the clear majority and could call the shots, Mainstream had no problem being part of a global church. But now that the U.S. is moving toward being a minority of the General Conference delegates, Mainstream wants to back down from being a global church and adopt a regional autonomy model.

This move toward regional autonomy has the potential of weakening the international connection between various parts of The United Methodist Church. It is the equivalent of the eye saying to the hand, “I don’t need you.” Or the head saying to the feet, “I don’t need you” (I Corinthians 12:21). While it is understandable that Methodists who do not agree on foundational issues might choose to govern themselves separately, it seems to reflect a hypocritical attitude to say, “We want to be all part of the same church, but we don’t want you to influence our decisions on how to be church.”

In any case, the regionalization proposal seems to reflect a renunciation of the attempt for the UM Church to be a global denomination, and it moves the church toward being a confederation of regional or national churches.

A Faulty Understanding of the Globalization of United Methodism

Mainstream UMC portrays the growth of international United Methodism as the result of decisions made by General Conference to “absorb global annual conferences” beginning in the 1990s. However, that is only true of the Cote d’Ivoire Annual Conference in Africa. Its 677,000 members at the time were admitted by the 2004 General Conference for partial representation at the 2008 General Conference and for full representation at the 2012 General Conference.

When the UM Church was formed in 1968, annual conferences outside the U.S. were given the choice of whether to become autonomous Methodist churches or remain in the UM Church. The Board of Global Ministries actively encouraged conferences to choose to be autonomous. All of the annual conferences in Latin America and most in Asia chose that status. The small conferences in Europe and in Africa (at the time) chose to remain United Methodist.

Then what accounts for the shift in the percentage of delegates from being almost entirely U.S. to being more evenly divided? As Mainstream documents, General Conference delegates from outside the U.S. accounted for only 8 percent of the total in 1980, while it has grown to 44 percent today.

The first reason is the decline in U.S. membership. When the UM Church was formed in 1968, it had over 11 million U.S. members. Currently, it has declined to less than 6 million U.S. members even before disaffiliation began. Through disaffiliations, the U.S. church stands to lose an additional 1 million members. If growth of the U.S. church had kept up with the growth in U.S. population over that time, there would now be 18.7 million U.S. members, over 70 percent of total UM membership.

The second reason is the dramatic growth of members in Africa. Just as an illustration, while Cote d’Ivoire had 677,000 members in 2004 when it was received into the UM Church, it now has double that number at 1.2 million. In 2005, the Congo Central Conference had 1.2 million members in 12 annual conferences. It currently has 3.7 million members in 14 annual conferences. Many other African annual conferences have also experienced exponential growth. The UM Church has usually seen that growth as something to celebrate. Mainstream seems to view it as a threat to U.S. dominance and a reason to separate the U.S. as its own regional governing structure.

The third reason for the shifting imbalance is the provision in our Constitution that gives every annual conference at least 2 delegates, one clergy and one lay. This has resulted in an imbalanced representation from Europe and the Philippines. The 20 European annual conferences have 40 delegates, which gives them one vote for every 1,300 members. This is far above the churchwide average of one vote for every 14,500 members. (Note that Mainstream’s chart of delegates dates from the 2016 General Conference. I am using the more recent 2020 numbers.)

Similarly, the Philippines has intentionally taken advantage of this system to multiply the number of annual conferences there. They have 26 annual conferences, giving them 52 delegates, or one vote for every 2,700 members.

Mainstream UMC tends to focus on Africa, however, since their 278 delegates dwarf the 92 other international delegates. The African delegates also tend to vote in a much more uniformly conservative direction, while Europe and the Philippines have been more evenly divided between conservatives and progressives. However, Africa is actually underrepresented for General Conference delegates, at one vote for every 19,000 members. If Africa were fairly represented based only on professing lay membership, it would have 42 percent of the delegates, rather than the 32 percent it currently has.

Mainstream portrays the allocation of delegates at General Conference as a “growing imbalance.” What they really mean is that the U.S. is receiving a shrinking percentage of the delegates. This is hardly an imbalance, but rather reflects the shifting membership in the global UM Church. The overrepresentation of Europe and the Philippines could be corrected by changing the formula allocating at least two delegates per annual conference to two delegates per episcopal area. But the root issue is the long-term and increasing decline of U.S. membership. The only way for the U.S. to maintain its percentage of the General Conference delegates is for the U.S. part of the church to start growing, which it has not done since the 1950s.

Relying on a faulty understanding of the growing globalization of the UM Church leads to “blaming” General Conference decisions for increasing international membership. This in turn leads to searching for a General Conference solution to the shifting representation, namely regionalization. It is a mechanism for the U.S. church to maintain its governance status quo without addressing the root issue of its 55-year membership decline. It is adopting a bureaucratic solution to a missional problem. Such an approach sustains the decades-long denominational ineffectiveness and holds no promise for a quick turnaround to growth in the future UM Church.

This Perspective has observed that, to the extent that Mainstream UMC speaks for the broad center of United Methodism, the future UM Church is likely to adapt to cultural trends, rather than maintain biblical distinctiveness. It is likely to weaken its global nature and connection. And it is unlikely to address its membership decline in the U.S.

Next week’s Perspective will examine more implications of the Mainstream UMC regionalization proposal.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Jul 14, 2023 | Home Page Hero Slider, In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

Surf City Disaffiliation or Eviction? —

The Los Angeles Times recently published a comprehensive 2,000 word piece about the excessively costly disaffiliation process for traditionalist United Methodist congregations in Southern California. It is worth reading to gauge the level of turmoil and pain within the denomination-wide schism.

Every annual conference has set different requirements for a congregation to disaffiliate. The California-Pacific conference is one of three to charge 50 percent of the price of their property – in addition to the normal fees and pension liabilities that are required by other annual conferences around the nation. Baltimore-Washington and Peninsula-Delaware are two others.

Elsewhere, California-Nevada is charging 20 percent, while South Carolina and West Virginia are charging 10 percent of the price of their property. Mountain Sky is charging a negotiated percentage of property value. Oregon-Idaho is adding some extra costs, but not a percentage of property value. Pacific Northwest and Alaska are not requiring extra costs. Neither is Desert Southwest.

According to the July 1 Times story from reporter Eric Licas, there are 22 Southern California churches attempting to disaffiliate from The United Methodist Church. The arbitrary financial requirements are proving to be major impediments in the fate of these small congregations.

“This annual conference and a couple others out there are adding onerous provisions for disaffiliation that make it literally impossible,” said the Rev. Glen Haworth, lead pastor of The Fount, a United Methodist congregation in Fountain Valley, California. “My church has 50 members, and they want $3 million dollars,” he told Licas. “And they say that’s fine, that’s fair. I say: fair to who?”

For small congregations like Haworth’s, the annual conference cost requirements seem insurmountable.

The in-depth story in the Times focuses on a neighboring congregation, Surf City Church in Huntington Beach, a community 30 miles south of Los Angeles. That congregation sought to disaffiliate, but was closed by the conference instead.

The superintendent of California Pacific Conference’s South District, the Rev. Sandra Olewine, told the paper that Surf City Church – a United Methodist congregation – had been deemed “unviable” after “10 years of efforts to revitalize and focus the mission and ministry there.” According to Olewine, the conference leadership made the decision to close the church.

“[Surf City Church] is no longer a chartered congregation and due to the failure to participate in the mission congregation process that designation was terminated on December 31, 2022,” Olewine told the reporter. “They have no official standing in the denomination any longer.”

Understandably, laypeople from the Huntington Beach congregation are seeing the very painful story through a different lens.

“People in the pews, they’re the ones who are just unbelievably disappointed that they were part of a church that would say the kind of things and do the kind of things and take the kind of actions the church has taken,” John Leonard, a member of the Surf City Church board of trustees, is quoted as saying in the paper.

Leonard told the reporter that Surf City Church existed as a congregation long before it joined the United Methodist Church and that their sanctuary, preschool, fellowship hall and the rest of its facilities were all paid for by members of the community.

“The conference didn’t pay a cent for any of that,” Leonard said.

According to the newspaper account, Surf City was launched in 1904 as a “tent church” on the shore in Huntington Beach.

The newspaper reports that “members of the local congregation claim they have been harassed by parties representing their parent denomination, according to Leonard and [fellow board member Marge] Mitchell.” That interference includes harassment of the church’s preschool.

According to the reporting, “Earlier this year, [members of the congregation] received an email claiming they were illegally operating their preschool and had to shut it down. That was followed shortly thereafter by a visit to the school by state inspectors who said they were responding to an anonymous tip. However, [the inspectors] found no issues.”

Terri King, another Surf City member, handles the finances for the preschool that serves about 95 students from the community. When she tried to pay the teachers, King discovered that the “accounts holding their wages had been frozen by attorneys for the conference.”

In past years, the congregation has hosted a summer program for kids, but they have cancelled it this year “because we have no guarantee that we will be able to pay the teachers,” King told the paper.

Worship services, Bible studies, and other programs are being hosted at the church with the assistance of guest pastors. “Members still shuffle into their sanctuary’s pews and take inspiration from its stained glass windows,” reports Licas. “Most remain committed to their faith, even if they’re practically regarded as squatters by the conference.”

The members of the Huntington Beach congregation are awaiting a final decision “outlining exactly how ownership will be transferred,” although attorneys for the conference have “unsuccessfully filed motions to allow them to seize it immediately,” reports the paper.

“The issue of homosexuality and same-sex marriage is the presenting issue currently,” the superintendent, the Rev. Sandra Olewine, wrote in an email to the reporter on June 23. “But there are other challenges we must face that have existed for far too long: systemic racism, persistent sexism, and impacts of colonialism both within the U.S. and globally are just a few. How to be church as we approach the second quarter of the 21st century is up for grabs. We are amid a period of reformation, which is not a bad thing, but it is a challenging thing.”

Concerned laypeople within the congregation believe the denomination is “trying to leverage its survival against what they describe as a ransom on those trying to part ways with it.” They are hoping for a reformation of a different kind with a peaceable resolution.

To read the entire story in the Los Angeles Times, you may click HERE. Photo: Lone surfer at Huntington Beach. Photo by Steve Beard.

by Steve | Jul 7, 2023 | In the News, Perspective E-Newsletter

Engaging an African Bishop —

By Thomas Lambrecht —

A recent commentary by Bishop Mande Muyombo (North Katanga Area in the Congo Central Conference) sets forth his understanding of where things are and where things are headed for The United Methodist Church in Africa. Given Muyombo’s position of power within the church’s hierarchy, it is appropriate to engage with the vision he puts forward.

Muyombo begins by quoting a 2019 statement by the African college of bishops. “We cannot allow a split in the church to further reduce us to second-class citizens in a church that only needs us when they want our votes. We have been second class for too long. We believe that as Africans, we have the right of self-determination, and … the right to speak for ourselves and determine who we want to be.”

It is an oft-repeated myth that United Methodists, particularly traditionalist UM’s, only care about Africa when their votes are needed at General Conference. Certainly, the church as a whole has been involved in missions in Africa for generations. Many of the missionaries who evangelized Africa and helped build the church there belonged to the traditional wing of Methodism. Even in the last decade, many traditionalist U.S. congregations have supported mission projects in Africa, built dozens of church buildings, sent volunteer teams, provided educational scholarships, and invested in evangelism and health projects.

Filling in the Gaps

What has been missing from the general church was a way to equip and empower African leaders to participate on an equal basis in the governing process of the denomination through its committees, board, agencies, and General Conference. Africans have been persistently underrepresented in the governance structure of the UM Church. Through the efforts of African delegates supported by traditionalists, some of that underrepresentation has been addressed, but not all. In the 2024 General Conference, African delegates will make up around 35 percent of the delegates, while African church members make up over half the denomination’s membership – even before disaffiliations started in the U.S.

Just having Africans at the table is not enough to enable them to participate as an equal voice. African delegates are often left out of the loop when it comes to sharing information. African delegates are often the last to receive the advance edition of the legislation submitted to General Conference, with some delegates only receiving it upon their arrival a few days before the beginning of General Conference. Because many delegates do not have access to the Internet, especially in their native language, they cannot follow the development of ideas and proposals over time.

The traditionalist Renewal and Reform Coalition has been instrumental in providing information to African delegates about developments in the church, as well as specific proposals coming to General Conference. The Coalition has offered training to African delegates about how to maneuver through parliamentary procedure and accomplish their legislative goals. We have offered assistance in writing and submitting legislation, as well as mobilizing support for African initiatives, such as the addition of five new bishops in Africa. Where the general church has left a gap in fully including African delegates in the governing process of the church, the Coalition has stepped in to fill those gaps.

Cynical Manipulation?

Some have viewed the Coalition’s participation as a cynical attempt to manipulate African delegates to support traditionalist legislation. On the contrary, the Coalition’s work has enabled Africans to voice their own concerns and perspective more fully. With support of other delegates, Africans were elected as officers of legislative committees to a greater extent than ever before. With the support of the Coalition, the Judicial Council has a majority of its elected members from outside the U.S.

No one has to convince or manipulate the African delegates to vote for traditionalist positions on issues of concern. Africans in general believe and maintain traditionalist views. Rather, the Coalition’s work has been to help delegates understand the details and implications of legislative proposals, so that they can vote according to their own consciences and perspective.

“Using” African United Methodists?

Muyombo charges that “The leadership of the Wesleyan Covenant Association/Good News and the Global Methodist Church have been attempting to divide our church in Africa. African United Methodists must resist being used as proxies of the Global Methodist Church and other U.S. breakaway groups.”

The division in Africa is real. It is surprising that Muyombo is unaware of the grassroots sentiments.

We categorically reject the accusation that we are somehow “using” African United Methodists or that they are “proxies” to fight our battles for us. American traditionalists have been fighting to uphold United Methodist doctrine and discipline for decades before the African church grew to the place of influence it now holds.

We are simply making available to African United Methodists information that is being intentionally withheld from them by their bishops and other leaders. Many of them know very little about the separation happening in the U.S. church and have no knowledge about any options for disaffiliation that may be available to them.

The Need for Self-Determination

It is interesting that Muyombo addresses African United Methodists with the call, “I invite you to exercise self-determination and speak for yourselves based on your own experience and that of your church community.” He says, “We believe that as Africans, we have the right of self-determination, and … the right to speak for ourselves and determine who we want to be.”

This is from the same bishop who suspends and even evicts from the church any African leader who tries to share information about what is happening so that Africans can indeed speak for themselves and exercise their self-determination. Muyombo and some other African bishops have forbidden African leaders from equipping their members to make the very decisions that Muyombo says he believes they ought to make.

African delegates to General Conference should be able to hear point-counterpoint presentations about the issues before The United Methodist Church. Bishop Muyombo and his colleagues should empower and freely release the delegates to make up their own minds.

The Renewal and Reform Coalition believes Africans can and should decide for themselves what future they want to be part of. If African United Methodists want to be part of a church that affirms LGBT practices and changes the definition of marriage to include same-sex couples, that is their decision, and we support their right to make it. At the same time, we believe African United Methodists should have the ability to decide not to be part of such a church – a right they are currently being denied.

How can Muyombo speak of “self-determination” when he denies that right to his own people? He quotes with approval the statement by the African college of bishops that, “Even if The United Methodist Church splits, Africa will continue to be a United Methodist Church.” Should that not be a decision for African United Methodists as a whole? This sounds less like “self-determination” and more like “bishop determination.” It makes a mockery of Africans’ ability to “determine who we want to be,” substituting instead “determining who our bishop wants us to be.”

Teaching Founded on Culture and Context?

In connection with the presenting issue of sexuality and marriage, Muyombo quotes the African college of bishops’ statement as saying, “As an African United Methodist Church, we do not support the practice of homosexuality because it is incompatible with most African cultural values and contextual realities.” Not because it is incompatible with the Bible or with 2,000 years of Christian teaching. Rather, it doesn’t fit African culture and context.

Of course, culture and context can change. Does Muyombo envision a time down the road when African culture will change to accept the practice of homosexuality? What about other areas where African culture and context opposes biblical teaching? Should the church side with culture over the Bible?

When one builds the church’s teachings on the shifting sands of culture and context, there is no telling where that will lead. It will certainly not result in a church that consistently maintains faithfulness to historic Christian faith and practice. (Of course, we face this same problem in the U.S., where we have allowed some cultural ways to warp the church’s teaching and practices.)

Neither Good News nor the Renewal and Reform Coalition has sought to “divide” the church or seek its “dissolution” as Muyombo charges. Instead, we have fought for 50 years to uphold traditional Methodist doctrine and teaching, seeking to reform the denomination to preserve accountability to our stated doctrines. Only when it became apparent that widespread rejection of some traditional doctrines and practices would go unchecked did we state the reality that we could no longer live together in one church.

At that point, it seemed most prudent to foster a separation that would allow traditionalist Methodists to maintain historic doctrine and practice, while allowing more progressive Methodists to pursue the revisionist path they had embarked upon. We hoped such separation would happen amicably with mutual respect and grace. Instead, institutional United Methodism in many cases has fought tooth and nail to prevent gracious self-determination by congregations and clergy seeking an expression of Methodism more faithful to their beliefs. Muyombo and some other African bishops are part of that institutional resistance that seeks to preserve personal status and power at the expense of grass roots self-determination.

We call upon all bishops and institutional leaders to allow gracious self-determination by their members, whether in the U.S. or Africa or other parts of the world. Only free and informed decision-making by members will result in a church that is unified in a mission and vision for the future.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Jul 1, 2023 | In the News, Sept-Oct 2023

Methodist Heritage: Brother Stanley —

By Edmund Robb III —

Good News Archive, July-August 1976 —

TIME magazine, Oct. 20, 1948: “A grand old man among U.S. missionaries is a rugged Methodist preacher named Eli Stanley Jones. Baltimore-born Missionary Jones went to India in 1907, and his 35 busy years there made him one of India’s best known and respected Americans. His preaching has converted many a Hindu and Moslem to Christianity; his 14 books (best known: The Christ of The Indian Road) have quickened the faith of Christians all over the world.”

Little did the Time editors realize how rugged this “grand man among U.S. missionaries” really was! What was apparently intended as a career epitaph report, wasn’t. His “35 busy years” stretched to 61. His “14 books” increased to 27. And the number of his converts swelled dramatically.

Dr. Jones – “Brother Stanley” – never seemed willing to quit. He often said, “When I die and get to heaven, I will take the first 24 hours to rest, the next 24 hours to seek out and talk with my friends, then I think I will go to Jesus and say, ‘Lord, do you have any other lost worlds where you need an evangelist? Please send me.’ ”

E. Stanley Jones – energy extraordinary! But it wasn’t always that way. In fact, he almost died of appendicitis in 1914. Only an emergency midnight trip from Sitapur to Lucknow in an army truck saved him – and even then he almost didn’t make it because 10 days after his operation tetanus set in. It looked as though Jones’ missionary career was over.

Somehow, he survived. Later, Brother Stanley recounted, “I had no intention of dying.” But within a few months the young missionary suffered the first of several nervous breakdowns. Eight years of strain in India had taken their toll, and so he was furloughed back to America for a year of recuperation.

Then he returned to India – and collapsed again. He later wrote, “I went to India with a deepening cloud upon me. Here I was beginning a new term of service in this trying climate and beginning it – broken.

“I saw that unless I got help from somewhere, I would have to give up my missionary career, go back to America and go to work on a farm to try to regain my health. It was one of my darkest hours. At that time – while in prayer, not particularly thinking about myself – a Voice seemed to say, ‘Are you yourself ready for this work to which I have called you?’

“I replied: ‘No, Lord, I am done for. I have reached the end of my rope.’

“The Voice replied, ‘If you will turn that over to Me and not worry about it, I will take care of it.’

“I quickly answered, ‘Lord, I close the bargain right here.’ That moment was the turning point of E. Stanley Jones’ missionary career – indeed, of his whole life!

The Voice was nothing new to Brother Stanley. He had been listening to it since college days – and it had led him to India. He later wrote, “At the close of four years here [Asbury College, 1906], I was perplexed and needed guidance as to where I should spend my life. At that particular moment I received a letter from the college president saying, ‘It is the will of the townspeople, it is the will of the faculty, it is the will of the student body, and we believe it is the will of God for you to come and teach in this college.’“

At that same moment he got a letter from a friend saying, “I believe it is the will of God for you to go into the evangelistic field here in America.”

He then received a letter from the Methodist mission board saying, “It is our will to send you to India.”

“Here was a perfect traffic jam of wills!” he recalled. “I had to get my way out, to find my way into clearness. I … knelt down in my room, spread [the letter] out before God, and said, ‘Now, my Father, my life is not my own. Anywhere you want me to spend it, I will go.’

“Just as quietly the inner Voice said, ‘It is India.’ I arose from my knees, sure it was India.”

And so, E. Stanley Jones went to India at a critical period in its history. The country was in a great flux. The India which he saw was fascinating, alluring, but paradoxical. He described it:

“The Indian Road! The most fascinating Road of all the world. Every Road seems tame alongside this Road. There is no sameness here; and hence no tameness. A surprise awaits you at every turn.

“On this Road you will find the world’s most beautiful building the Taj Mahal – cheek by jowl with the world’s most miserable hut. Here men disdain the world as evil and money as base, and yet on certain days will worship their own account books. … Here you will find the gentlest souls of the world … alongside of which you will find an explosive mentality….”

In 1907, young Jones landed in Bombay. His first impressions struck him like a blow. “People were lying on beds in the day time under trees, or they moved about very slowly. I was used to life keyed up and energetic. Here life seemed to be run down and tired. Its poverty seemed to be accepted and life had adjusted itself to that fact.”

Though respected as a missionary, it was Jones’ prolific writing which brought him into world prominence. Since publication of his first book in 1925, he averaged authoring a book every two years. In addition he wrote scores of magazine articles.

After his death in 1974, his daughter, Eunice, and son-in-law, Bishop James Matthews, wrote, “Some of his books have become modern Christian classics … translated into more than 30 languages.”

Strangely enough, “It was almost by chance that E. Stanley Jones became a writer. It developed from his preaching. Dr. Ralph E. Diffendorfer of the Methodist Board of Missions suggested in 1925 that he incorporate into a book the addresses he had been delivering all across America the previous year. These were based on his missionary work among the intellectuals of India, with whom he had developed an unusual rapport. The unexpected result, a month later, was The Christ of the Indian Road, an immediate best seller.”

At age 83, Stanley Jones began his third autobiography. (He had scrapped the other two.) When asked why he chose to write his own biography, Stanley Jones characteristically replied, “If anyone else writes it, they’ll talk only about E. Stanley Jones, but if I do it, it will be about Jesus.”

In spite of his writing success, until his death Jones insisted, “I am not a professional writer. I have not written for the sake of writing, nor for the sake of material gain. Rather, I have seen a need and have tried to meet that need.”

Brother Stanley wanted to be known not as an author – but as a witness for Jesus Christ. Since the beginning of his long ministry, this was his sole goal.

He once wrote, “I think the word ‘evangelist,’ the bearer of good tidings, is the most beautiful word in our language descriptive of vocation. I have been tempted to desert the name, for it has fallen on evil days and has a bad odor, but I have never been able to let it go, for it would not let me go.”

At one point in his ministry, Jones came near to missing his way as an evangelist. While home from India attending General Conference, he was elected a Methodist bishop, though he had earlier withdrawn his name from consideration. After a restless night Jones decided, “A mistake had been made and I knew it. I was headed in the wrong direction.”

“Bishop” Jones was miserable but he revealed his doubts to only one man, a trusted and loved bishop. His reply was, “You’ve got to go on, no matter how you feel.”

Nevertheless, “Bishop” Jones listened to another voice – The Voice.

Jones recounts: “I went straight to the chairman, Bishop Johnson, and said I had a matter of high privilege. … He had to let me go on. I read my resignation, thanked them for the high honor … walked straight off the platform, out of the building at the back and down the street to my train. I did not wait to see if my resignation would be accepted. I was hastening to get back to the Indian Road – as an evangelist.”

Stanley Jones had learned the importance of being a witness (an evangelist) during his very first sermon. He had prepared for three weeks, feeling that he should act as God’s lawyer and plead His case for Him.

The little church was filled with relatives and friends, all anxious that the young man should do well. All went smoothly until he used the word, “indifferentism.” A young college girl smiled and put down her head. This unnerved him so much that he went blank. “I stood there clutching for something to say.” Finally he blurted out, “I am very sorry, but I have forgotten my sermon.”

On his way back to his seat, Jones heard the inner Voice say to him, “Haven’t I done anything for you? If so, couldn’t you tell that?”

Young Jones stepped down in front of the pulpit and said, “Friends, I see I can’t preach, but you know what Christ has done for my life, how He has changed me, and though I cannot preach, I shall be His witness the rest of my days.”

At the close of that service a youth was saved. Jones had learned a lesson – God wanted him as a witness, not a lawyer.

Brother Stanley was a faithful witness. He was fond of saying, “My theme song is Jesus Christ.” And He was. Long before the Jesus Revolution popularized the “One Way” sign of Christian faith, Jones used a three-finger sign of Christian discipleship. He would smile, hold up his right hand with three fingers extended, symbolizing one of the basic facts of his life: “Jesus is Lord.”

Christ was the focal point of Brother Stanley’s faith – and his life. “I will have to apologize for myself again and again,” he would say, “for I’m only a Christian-in-the-making. I will have to apologize for Western civilization, for it is only partly Christianized. I will have to apologize for the Christian church, for it, too, is only partly Christianized. But when it comes to Jesus Christ, there are no apologies upon my lips, for there are none in my heart.”

Stanley Jones was especially gifted in adapting new methods to present his constant message Christ. One such example is the Ashram (ah’ shrum) movement, which he brought to America.

Ashram is an Indian Sanskrit word, meaning “a retreat.” In India, an Ashram is a place where a guru, or spiritual leader, and his disciples go apart for disciplined spiritual growth. Jones combined this ancient Indian format with the Christian Gospel, and the result was an overwhelming success. (About 150 Christian Ashrams now meet annually around the world.)

One of the reasons for Ashrams’ popularity is their openness. “When we come into the Ashram as members,” Jones explained, “we lay aside all titles. There are no more bishops, doctors, professors – there are just persons. We call each other by our first names …. “ Hence, the Rev. Dr. Eli Stanley Jones became known to millions around the globe simply as “Brother Stanley.”

Above all, Brother Stanley was a disciplined person. His son-in-law, Bishop Matthews, characterized him as “the most disciplined man I have ever known, so much so that at times he seems in this respect almost an anachronism in this century.”

Disciplined, indeed! Every night at 9:30 he would excuse himself to exercise and pray. He prayed one hour every morning and evening – regardless.

Bishop Mathews said of him: “He is constantly reading; constantly writing; constantly replying to his extensive correspondence; constantly traveling …. “

But in spite of his relentless pushing, Brother Stanley is remembered by many as a “fun” person. For example, Rev. Dr. J. T. Seamands, Professor of Missions at Asbury Theological Seminary, and long-time colleague of Jones, shares the story of the time he and Dr. Jones were eating at a Japanese inn. Their repast was revealed to be octopus feet, two sparrows, raw fish, and seaweed. Upon examining the meal before them, Dr. Jones exclaimed: “Where He leads me I will follow; what He feeds me I will swallow!’’

Brother Stanley was full of life because he walked with the One who said, “I am Life.” He knew the Source of his indefatigable strength.

Jones frequently said, “One day you’ll pick up the newspaper and read that Dr. E. Stanley Jones is dead. Don’t you believe a word of it. I’ll never be more alive than at that moment; and should you look into my casket with a glum face, I’ll wink at you.”

POSTSCRIPT: TIME magazine, Jan. 23, 1973 – Died: Dr. E. Stanley Jones, 89, Methodist clergyman from Maryland, who became one of the world’s best known evangelists; in Barielly, India. . . .

Edmund Robb III was the associate editor to Good News at the time of this article’s publication. This article appeared in the July-August 1976 issue. Dr. Robb went on to be the founding pastor of The Woodlands United Methodist Church in The Woodlands, Texas.

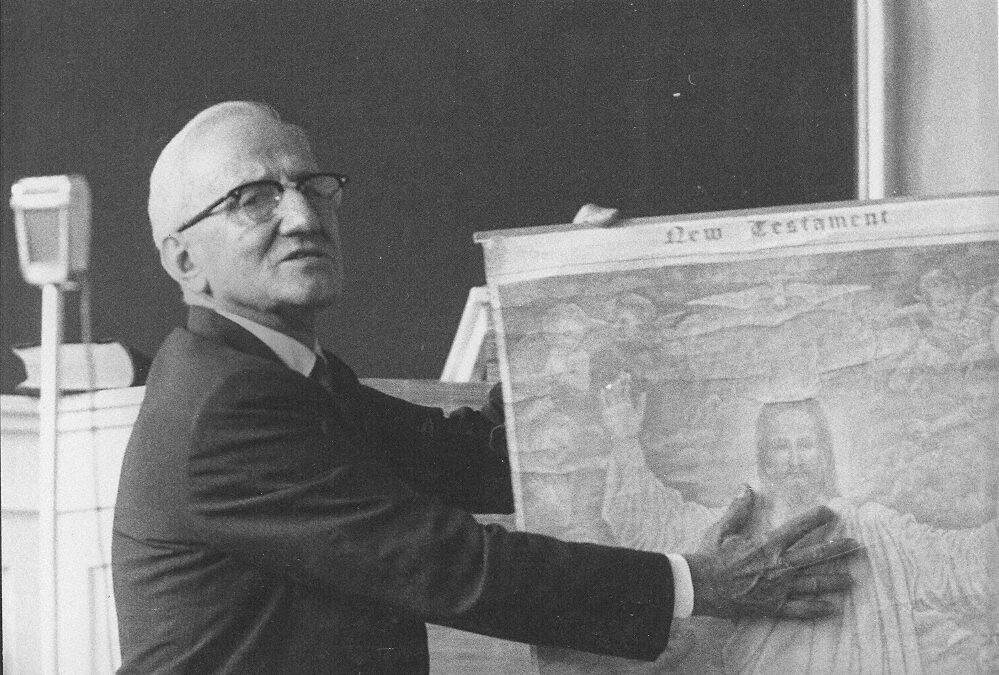

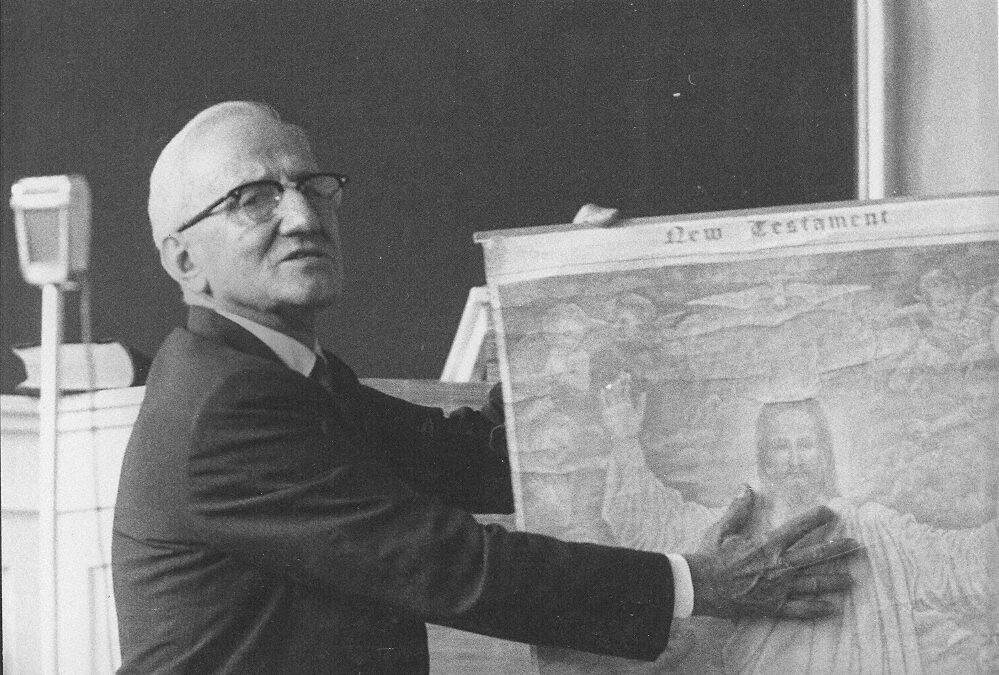

Photo: E. Stanley Jones showing poster of Jesus as the Word became flesh at Nykarleby, Finland Ashram, 1963 (courtesy of Asbury Theological Seminary special collections).