by Steve | Aug 18, 2025 | Front Page News, Home Page Hero Slider, Juloy-August 2025

Yesterday & Today: Church of God in Christ —

By John Mark Richardson, Sr. —

The Church of God in Christ (COGIC), a Holiness-Pentecostal denomination, has a deep spiritual heritage dating back to over 128 years. It has become one of the largest denominations in the United States and is the largest Holiness-Pentecostal denomination worldwide. It is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of African American faith, experience, suffering, resilience, hope, and community.

The COGIC was founded by Bishop Charles Harrison Mason, Sr., who was born on September 8, 1866, (although some records have 1864) in Shelby County, Tennessee, just over a year after the end of the Civil War. He was the son of former slaves and worked alongside his parents as sharecroppers throughout his adolescent years.

Mason grew up during a difficult and challenging era in America, particularly for African Americans. In a nation that had just torn itself apart primarily over the preservation of slavery and Southern states’ rights, survival was no easy feat.

The family of Bishop Mason faced the pervasive and devastating poverty that afflicted many Black individuals and families and Black communities following the Civil War. Amid this turmoil, Mason’s mother fervently prayed for her son, asking that he would be dedicated to God. Her prayers had a profound impact, inspiring the young Charles Mason to not only dedicate himself to God but also to incorporate daily prayer into his life. He earnestly prayed alongside his mother, asking above all things for God to grant him a religion like the one he had heard about from the old slaves and seen exemplified in their lives. This deep yearning for the God of his forebears became a central theme in his life, shaping his spirituality and purpose.

In 1880, just before his fourteenth birthday, Mason fell gravely ill with chills and fever, leaving his mother in despair over his life. However, in an astounding turn of events, he experienced a miraculous healing on the first Sunday of September that year. Eager to express their gratitude, Mason, along with his mother and siblings, attended church the following Sunday, at the Mt. Olive Baptist Church near Plumerville, Arkansas. An atmosphere of praise and thanksgiving enveloped the congregation as Mason’s half-brother, the pastor, baptized him, marking a transformative moment in Mason’s life after surviving a near-death experience.

During this moment of celebration, Mason said to his family and the local parishioners, “I believe God has healed me for the express purpose of alerting me to my spiritual duty.” From that moment on, Mason acknowledged and felt called into full-time ministry throughout his teenage and young adult years. His gratitude to God for his miraculous healing, his profound love for God, and his yearning to experience God like the saints of old fueled his desire to serve in ministry and live a life pleasing to God.

Mason’s Holiness Influencers

This deep sense of purpose and spiritual awakening naturally drew Mason towards the Holiness movement, which was making great strides in America during the 19th Century. This movement emphasized personal piety, sanctification, and a deeper, experiential faith, where adherents sought to experience God’s grace and power in transformative ways. Consequently, Mason attended various Holiness meetings and embarked on a quest to explore the Holiness movement further, eager to understand sanctification and embrace the sanctified life.

Mason’s readings on holiness and entire sanctification by various writers — John Wesley in particular — helped him establish roots in the Wesleyan tradition. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, championed the notion of personal holiness and social justice. Mason embodied these Wesleyan distinctives, and the Wesleyan Quadrilateral — scripture, tradition, reason, and experience — shaped Mason’s theological framework, integrating biblical authority, rich traditions, and vibrant spiritual experiences.

Additionally, and more importantly, Sister Amanda Berry Smith’s Holiness’s writings helped shape Mason’s beliefs and teachings that would lead to the Church of God in Christ’s deeply held beliefs and practices. Amanda Smith (pictured below) was a notable figure in the Holiness movement during the late 19th century. She was an African American evangelist, writer, and one of the first Black women to gain prominence in the Holiness and Pentecostal movements.

Amanda Smith’s writings and preaching focused on holiness and empowerment, significantly influencing many, including Bishop Charles H. Mason. Her work highlighted the importance of spiritual transformation and the experience of entire sanctification — a doctrine asserting that believers could attain a second work of grace that cleansed them from sin and empowered them for holy living and service in the present world. This doctrine resonated deeply within the African American church community, particularly for the Church of God in Christ and Bishop Mason, who claimed the grace of divine sanctification after reading Sister Amanda Smith’s autobiography.

After immersing himself in the writings of John Wesley, Sister Amanda Smith, and others, and experiencing entire sanctification during prayer, Mason’s life was transformed. However, his teachings on holiness and his fervent discussions about spiritual empowerment caused significant friction with the established order of the Baptist Church. In the 1890s, as he began advocating for sanctification and a more spirited form of worship, he found himself at odds with church authorities. His passionate emphasis on holiness was viewed as radical and contrary to traditional Baptist teachings.

Excommunication, Disputes, and Disfellowship

This escalating tension reached a culmination when Mason was formally excommunicated from the Baptist Church due to his beliefs and teachings regarding holiness. Consequently, this pivotal moment motivated Mason to team up with a former Baptist Pastor, Reverend Charles Price Jones, who was expelled from his pastorate for preaching holiness. These two incredible leaders collaborated to promote and disseminate the Holiness message more broadly. They did this through preaching, revivals, planting Holiness churches, providing guidance to pastors and churches wanting to embrace the holiness life, publishing literature, and writing inspired hymns and songs of praise.

This holiness fellowship and movement, led by two influential African Americans, attracted many to their cause. During this time, Bishop Mason (pictured below) received a revelation from God. In 1897, while walking and praying on a street in Little Rock, Arkansas, he heard God speak to him: “If you choose the name Church of God in Christ [based on 1 Thessalonians 2:14], there will never be a building big enough to hold all the people I will send your way.”

To this, Bishop Mason replied, “Yes, Lord!”

To this, Bishop Mason replied, “Yes, Lord!”

The collaboration between Mason and Jones was a beautiful but short-lived moment. Mason eventually experienced disfellowship from Reverend Charles Price Jones and others with whom he had served in ministry. After returning from the Azusa Street revival in Los Angeles, California, Mason’s report about the events he witnessed and his personal testimony of baptism in the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues were met with skepticism, criticism, and resistance. However, what Mason experienced at the Azusa Street revival reaffirmed his belief that God had more for His people to experience and receive — a third work of grace: power!

Mason was profoundly impacted by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit during the Azusa Street Revival, which manifested through various signs, including speaking in tongues, healings, and a deep sense of community among diverse groups of people. His reports highlighted the revival’s emphasis on holiness, the power of prayer, miracles, and the importance of evangelism.

Mason also noted the racial and cultural diversity present at Azusa Street, which broke down barriers between African Americans and Whites, creating a unique space for unity in worship. This experience of inclusiveness informed his later work in establishing COGIC as a vital denomination within the Holiness and Pentecostal movements.

The disfellowship was a painful experience. Mason and Jones were dear friends, and many in the group were close to Mason. Although Jones and Mason could no longer serve in the ministry together, they continued to respect each other as leaders and loved each other as brothers. Ultimately, Jones would establish a different faction of the Holiness movement, Church of Christ Holiness U.S.A., while Mason continued to promote his distinctive teachings and practices.

COGIC Holy Convocation, 1938. Courtesy Charles H. Mason & Mother Lizzie Robinson Museum (COGIC Museum)

The Formal Establishment of COGIC

By 1907, the seeds had been sown for the formal and legal organization of the COGIC. That year, Mason held a gathering in Memphis, Tennessee, where he officially established the Church of God in Christ as its own denomination.

This organizational meeting laid the groundwork for what would become a significant movement within the American religious landscape. Mason’s leadership was affirmed during this gathering as he was recognized for his theological vision, charismatic personality, and commitment to evangelism and spiritual empowerment. The attendees, composed of various clergy and laypersons inspired by Mason’s teachings and leadership, were the Church of God in Christ’s first General Assembly, and they voted to elect Bishop Charles Harrison Mason as the first Bishop of the COGIC.

The news and outcomes from this meeting attracted a diverse group of adherents to the Church of God in Christ, including many white congregants and preachers impacted directly or indirectly by the Azusa Street Revival, and who resonated with the tenets of Holiness. They embraced the radical inclusivity suggested by Galatians 3:28: “that in Christ, all believers are equal, regardless of their ethnic or social background.” As one affirmed, “the color line was washed away by the blood.”

An Interracial Denomination

From 1907 to 1914, the COGIC was arguably the largest interracial denomination worldwide. In congregations of the Church of God in Christ, black and white saints worked, worshiped, and evangelized together in an interracial, egalitarian fellowship modeled after the fellowship at Azusa Street. This occurred throughout the South, including Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia, during a particularly racially tense time in the United States.

Additionally, because the Church of God in Christ was legally incorporated, they could ordain clergy whose status civil authorities would recognize. Clergy who wished to perform marriages and other ministerial functions that had legal consequences needed this official recognition. Mason also played a crucial role in carrying out the Azusa Revival from its movement phase to its denominational phase. Through Mason’s influence, scores of white ministers sought ordination at the hands of Mason. Therefore, large numbers of white ministers obtained ministerial credentials carrying the name of the Church of God in Christ.

Many white brothers and sisters who formed the Assemblies of God had been part of the Church of God in Christ from 1907 to 1914, during which time Bishop Mason ordained about 350 white ministers. In 1914, the Assemblies of God was organized, and in the second week of April that year, Mason traveled to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to attend the organizing meeting of the Assemblies of God. He preached on Thursday night, illustrating the wonders of God by holding up an unusually shaped sweet potato. He sang his spontaneous improvisation of spiritual songs that Daniel Payne in 1879 referred to as “corn field ditties.” With Mason were the “Saints Industrial” singers from Lexington, Mississippi. Mason bid the white leaders a warm farewell and gave his blessing for the white ministers to form their own organization. He also gave them permission to void their Church of God in Christ credentials in order to switch to those of their new denomination.

Bishop Mason’s Tenure and Accomplishments

During his tenure as founder and first Bishop of the Church of God in Christ, Bishop Mason led the church through phenomenal growth while championing civil rights and social justice. He actively worked to create a more equitable society, standing against racism and Jim Crow discriminatory practices, all while supporting the United States government in its fight against Nazism and Fascism.

He oversaw the construction of the largest African American church campus of the early 20th century, featuring a sanctuary that seated five thousand worshippers. This historic landmark campus was where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech — just a day before he was tragically assassinated.

Above all, Bishop Mason was a holiness preacher, inspiring people to live free from sin. He was also unapologetically Pentecostal, embracing the gifts of the Spirit and advocating for baptism in the Holy Spirit and the fruits of the Spirit.

Following Bishop Mason

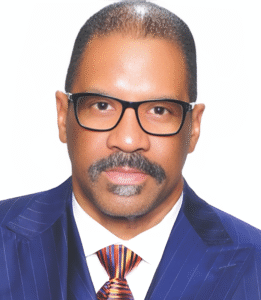

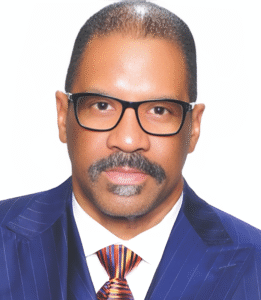

Bishop Charles Harrison Mason, Sr., the beloved founder and first Bishop of the Church of God in Christ, died November 17, 1961. He served the denomination he founded for fifty-four years. Since the death of Bishop Mason, seven leaders have served as Presiding Bishop: Ozro Thurston Jones Sr. (1962–1968); James Oglethorpe Patterson Sr. (1968–1989); Louis Henry Ford (1990–1995); Charles David Owens (1995–2000); Gilbert Earl Patterson (2000–2007); Charles Edward Blake (2007–2021); and John Drew Sheard (2021–pictured below).

Bishop Sheard of Detroit, Michigan, serves as COGIC’s Presiding Bishop, embodying the spirit of Bishop Mason in his leadership. He has been a gracious and kind leader, guiding COGIC into a time of organizational peace, unity, prosperity, and national and international influence. He has coordinated the completion of major building projects, repaired and beautified existing structures, paid off existing debt, and responded to national and global crises and tragedies that have impacted the COGIC family. Bishop Sheard has reformed ministerial education and training for clergy, the COGIC Seminary and University, and has helped transition the COGIC into a more digital and innovative era. Bishop Sheard has also led the church in embracing a multi-faceted approach to ministry, prioritizing spiritual growth and evangelism, while maintaining a strong focus on:

Bishop Sheard of Detroit, Michigan, serves as COGIC’s Presiding Bishop, embodying the spirit of Bishop Mason in his leadership. He has been a gracious and kind leader, guiding COGIC into a time of organizational peace, unity, prosperity, and national and international influence. He has coordinated the completion of major building projects, repaired and beautified existing structures, paid off existing debt, and responded to national and global crises and tragedies that have impacted the COGIC family. Bishop Sheard has reformed ministerial education and training for clergy, the COGIC Seminary and University, and has helped transition the COGIC into a more digital and innovative era. Bishop Sheard has also led the church in embracing a multi-faceted approach to ministry, prioritizing spiritual growth and evangelism, while maintaining a strong focus on:

• Youth and Education. The COGIC organization offers programs to engage young people in ministry and service, highlighting the importance of active, informed citizenship.

• Health Initiatives. Recognizing the critical health disparities in many African American communities, COGIC has implemented various health initiatives to promote wellness, access to care, and health education.

• Social Justice Activism. In response to contemporary social issues, COGIC has positioned itself as a leader in the conversation on justice, racism, and equity. This commitment echoes the church’s historical roots in the civil rights movement, as COGIC remains dedicated to lifting the voices of the marginalized.

• Global Outreach. By establishing missions in 112 nations, COGIC transcends geographical and cultural barriers, embodying Christ’s love in action.

• Connecting with the Wesleyan Tradition. The connection between COGIC and the larger Wesleyan family is not simply historical; it is a living relationship characterized by shared values and missions. As denominations continue to navigate modernity, COGIC stands with the Wesleyan movement with its emphasis on holiness and empowerment.

• Embracing Contemporary Challenges

As COGIC embraces its role in today’s society, it is also addressing contemporary challenges its congregants and communities face.

Looking ahead, the Church of God in Christ remains steadfast in its mission to spread the Gospel and serve local and global communities. It is poised not only to influence its members but to inspire churches across different denominations, including those within the Wesleyan family, to respond to the ever-changing landscape of faith and social responsibility.

By John Mark Richardson, Sr., is Regional Bishop, Church of God in Christ (COGIC), and Executive Director, Wesleyan Holiness Connection.

by Steve | Aug 18, 2025 | Front Page News, Home Page Hero Slider, Juloy-August 2025

Justified by Faith: Why the Details Matter — A Lesson from Making Bread —

By James R. Morrow —

How hard could it be? I had just tasted one of the best slices of homemade bread I’d ever eaten. Perfect texture, with a delightful taste (especially when slathered in butter!). I decided right then that I would make bread too. After all, it’s just flour, water, and yeast … or so I thought. Hours later, I tasted the most disappointing slice of bread I’d ever eaten.

A quick watch of “Bread Week” on The Great British Baking Show could have saved me a lot of trouble. It turns out, bread-making is more complex than it looks. You’ve got to pay attention to the type of flour, make choices about hydration levels, and don’t forget to activate the yeast! Then there’s rising and proofing times (cue Paul Hollywood declaring, “It’s underproved!”) and the mysterious world of gluten development. Yes, bread is bread, and we can find it almost anywhere. But the details make a huge difference. The more we understand about each part of the process, the greater our enjoyment of the final product.

Salvation is a lot like that.

Many of us can remember the first time we truly tasted salvation — an initial encounter with God’s grace that changed everything. That moment matters! But if we stop there, we risk missing the deeper beauty. Like baking bread, the details and distinct movements of human salvation matter. The more we understand what’s happening beneath the surface — what God has done, is doing, and will do — the richer our experience becomes. Paying attention to what occurs in salvation leads to a richer experience of the whole.

In the Wesleyan tradition, salvation is more than a single moment; it is the entire life of grace — a journey marked by God’s initiative and our continued response. God’s love meets us before we are aware of God (prevenient grace), pardons us from our sin (justifying grace), and reshapes us in holy love (sanctifying grace). Salvation is God’s work from beginning to end, from rescue to being made perfect in love, from alienation to union.

One of the first major movements in salvation is justification. It isn’t the whole story, but it is a vital part. It is the doorway to experiencing the fullness of salvation. Every subsequent experience of salvation rests on justification. That’s why it’s worth pausing to pay attention to what happens in this moment of grace.

What is Justification?

Simply put, justification is pardon. I like the way that John Wesley puts it in his sermon “On Justification”: “The plain scriptural notion of justification is pardon, the forgiveness of sins.” Justification brings a relative change in our status — from guilty to acquitted, from alienated creation of God to child of God, from lost to welcomed home. It is the work God does for us. (Regeneration and sanctification involve the work that God does in us.)

One way to picture this is through a legal metaphor. In the American legal system, a president or a governor can pardon someone who is awaiting trial or sentencing. That pardon nullifies all legal proceedings and releases the person from liability. When we are justified, God pardons us — fully. All of our past sins —whether in thought, word, or deed — are forgiven. All of them. We are washed white as snow. Our record is clean. The punishment is lifted.

The legal metaphor also helps us see how justification restores relationship. A criminal, once pardoned, can live again in good standing with society. Similarly, justification reconciles us to God. Once alienated from God by sin, we are welcomed into a right relationship and restored friendship with God.

Why We Need Justification

Reflecting on justification reminds us just how fallen we were. To be pardoned means that we were once guilty, condemned, and alienated from God. Scripture describes our natural condition as one of spiritual death, separation, and bondage to sin (Romans 3:23; Ephesians 2:1-3). We are not merely wounded or weakened; we are lost and utterly incapable of saving ourselves. This is true for all people, regardless of their status, morality, or religious efforts. Unless God acts, we are lost.

What God Has Done

Thankfully, God has acted. Romans 5:10 reminds us that we are “reconciled to God by the death of his Son.” Justification is possible because, in love, the Father sent the Son, who lived perfectly, gave his life for the world, rose from the dead, and now intercedes for us. And the Holy Spirit awakens our hearts, gives us grace to believe, and applies Christ’s saving work to our lives. (Notice how salvation is a Trinitarian thing!)

This is all God’s doing, accomplished through God’s love, for the sake of sinful humanity. No one deserves it, nor does anyone have the capacity to earn it — even those who have done seemingly good deeds. God justifies the ungodly, and all people prior to salvation qualify for that group.

The Role of Faith

There is only one necessary condition for justification: faith. As Ephesians 2:8 says, we are justified by “grace through faith.” Now, faith is not simply belief that God exists, that Jesus is real, or that forgiveness is a possibility. Wesley preaches that faith is “a sure trust and confidence that God both hath and will forgive our sins, that he hath accepted us again into his favor, for the merits of Christ’s death and passion.” In the spirit of Wesley’s own faith journey, we are reminded that faith is the conviction that Christ died for us, that our sins are forgiven, and that we, like the young prodigal son, are welcomed back into relationship with the Father.

I want to be clear here so that we don’t get tripped up by the YouTube apologists: faith is not a human work. It is only made possible by the grace of God. Without God acting first — by what we refer to as prevenient grace — we would have no capacity for faith. Our capacity for faith is an act of God to which we respond through surrender. God makes faith possible through grace, but God will not force someone to have faith. Justification, like all of salvation, is entirely an act of grace.

Let’s Talk About Some Questions

First, what about repentance — isn’t that important? Yes! While we can examine the various parts of the journey of salvation, that doesn’t mean they can be separated or cleanly delineated in real-life experience. Like ingredients in a loaf of bread, they’re all baked together. You can marvel at the results of gluten development and proofing, but you can’t separate them from the loaf. Wesley reminds us that repentance is a fruit of faith. Although it’s often all wrapped up together in experience, justification follows repentance as God’s pardoning work.

Second, isn’t this just “getting saved?” When people talk about getting saved, they’re often describing justification. And they’re not wrong. Justification is the moment when we’re pardoned, accepted, and set right with God. But that’s not all there is! Even in our initial experience of conversion, God is doing distinct but related work in us — namely, regeneration. If justification is the work that God does for us, regeneration begins the work that God does in us.

Wesley puts it this way in his sermon, “The Great Privilege of Those That Are Born of God”: justification “is the taking away the guilt,” while regeneration takes “away the power of sin.” He reminds us that “although they are joined together in a point of time, yet are they of wholly distinct natures.”

We don’t want to reduce salvation to justification any more than we want to reduce bread to flour, water, and yeast. But neither should we overlook the beauty and power of reflecting on what justification means in the life of salvation.

Why the Details Matter

Paying attention to the details of salvation — those distinct yet interconnected works of God — doesn’t complicate salvation. It enriches it. Justification isn’t just a theological concept; it’s a powerful work of God. It is a doorway. Through it, we step into the joy of full salvation.

When we pause to reflect on that moment — the pardoning mercy, new standing with God, the doorway swinging open to the fullness of salvation — we can celebrate just how deeply we are loved and find assurance that God has pardoned us.

That kind of reflection feeds our faith. It awakens worship, increases our gratitude, and sets our feet on the path of transformation. Justification may be the entryway, but from there, salvation unfolds one grace-filled room after another.

I’m a little better at baking bread these days, and I have a deeper appreciation for every bite of it I take. The details matter. And justification is one worth savoring.

(If you’d like to take a deeper dive into justification, I recommend reading John Wesley’s sermon, “Justification by Faith,” and grabbing a copy of Seedbed’s The Faith Once Delivered: A Wesleyan Witness to Christian Orthodoxy.)

James R. Morrow is an elder in the Global Methodist Church and lead pastor of the First Methodist Church of Albany in Albany, GA. Along with First Methodist Church, Jim is passionate about offering Christ from the heart of downtown for an awakening in Southwest Georgia.

by Steve | Aug 18, 2025 | Front Page News, Home Page Hero Slider, Juloy-August 2025

Unfolding Salvation —

By Ryan Danker —

This issue of Good News is dedicated to the work of God in Christ to make us whole, otherwise known as salvation. It is my hope that the articles contained here will help us to better understand the process, or order, or even way by which God calls each and every one of us to new life in him.

God’s saving work has always been at the heart of the Wesleyan revival. The early Methodist leaders weren’t launching revivals wherever they went. They were trying to keep up with the outbursts of revival, the restorative work of God. God was at work and they wanted to catch up with what he was doing. And his work involved the salvation of souls. He who created us, loves us, and wants us to live victorious lives. And ever since we turned from him, God has gone out of his way to bring about our restoration.

Just think of Jesus’ parable of the Prodigal Son. It has many meanings, but one of them is that the parable is a picture of God’s constant desire for us to return home, to return to him, even when we’ve insulted him, squandered our inheritance, and lived self-centered lives. In the parable we learn that when the father, even after all that the son had done, sees him from a distance, he runs to him and takes him into his arms. This is the loving embrace that awaits each of us. This is a picture of salvation.

From the moment of the Fall, when humanity sinned and brought death and corruption into the world, from that very moment, we begin to see God’s plan of salvation unfold. Look at the account of the Fall in Genesis, even there we catch small glimpses of God’s plan of salvation. Adam and Eve had broken the covenant that they had with God and the repercussions were disastrous for them and for the creation itself. God responded to their faithlessness by sending them away from the life that they were intended to live, a life that sin made no longer possible. But when God cursed the serpent that had beguiled them he spoke of the “seed” of the woman who will ultimately “bruise” the serpent’s head. The church fathers read this as a reference to Christ, born of Mary, the second Adam and the second Eve, from whom and through whom salvation would come.

The plan of salvation unfolds throughout the rest of Scripture. Even after the Fall, God continued to walk with his people, ultimately calling on Abram to become Abraham and Sarai to become Sarah, whose decedents would be a chosen people, a holy people set apart as a beacon of God’s work of restoration. He called the people of Israel to be his own so that they might cooperate with his work to bring wholeness and healing to the world.

Only in Christ, though, do we see the work come to fulfillment and completion. Only God incarnate, God with us, God as one of us, would the full healing begin, a new creation. Made one of us, he lived and died as one of us, saving us by his full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice on the cross.

Sin entered the world through our disobedience, but Christ’s death conquered sin. And the same victory that he won on the cross can be applied to your life and to mine. Sin doesn’t have the last word, even on this side of death. Christ’s resurrection by the Spirit of God, a new life, can also be ours as we receive a share of that ultimate life awaiting the general resurrection when we will be made fully like him.

The beauty of the Wesleyan tradition can be seen in its hope-fullness. Wesleyans have a sure hope that we can experience the saving work of God in our lives now. In fact the word “now” is a very Wesleyan word — and arguably a scriptural one. Once when writing to an early Methodist, Wesley — who was talking about the fullness of salvation — said, “Be a Methodist still! Expect perfection now!” The promise of salvation is not just a promise for a future time, but a promise that can be fulfilled and experienced now. Holy love, the life God intended for us from the beginning, can reign in our hearts now.

We can see this in the words of Charles Wesley in one of his striking hymns,

“O for a heart to praise my God

A heart from sin set free!

A heart that always feels thy blood

So freely spilt for me!”

Salvation is something that we can experience in this life and expect now, but it is also a process. There are certainly moments of great change within that process, but wholeness in Christ is a work that we must dedicate ourselves to, by grace, for our entire lives. We are to grow from grace to grace.

Wesley once talked about the process of salvation by using a house as an analogy, a picture of God’s work. He said, “Our main doctrines, which include all the rest, are three, that of repentance, of faith, and of holiness. The first of these we account, as it were, the porch of religion; the next, the door, the third, religion itself.” Salvation is driven by grace — the power of the Holy Spirit — and faith, our response to God’s offer of love.

What we describe as prevenient grace — which means the grace that goes before — is in reality God’s desire to be in relationship with all people. He calls to us like one seeking the lost. He is constantly seeking a loving relationship with each and every one of us, even when we’re not seeking him. This call or grace awakens us, takes the blinders from our eyes, and we begin to see our present situation, a situation where sin has the upper hand. This is sometimes called an awakening. One of the earliest names of people in the Evangelical Revival was actually “the awakened.” They knew that they needed God, and that only in him could they find true wholeness and peace.

When we are awakened to our need for salvation, seeing the depths of our sin and the mess we have made, we experience the need for God’s mercy and we are given a desire for God. And so by grace we turn to him in faith, which can also be understood as trust. Faith is the key, even as grace is the engine. In justifying grace we receive by faith the pardon of God who justifies us, forgives us, placing our trust in what Christ has done for us on the cross. And we’re not just seen to be justified, we are justified as the life of God becomes our own.

The Book of Common Prayer describes God as one “whose property [character] is always to have mercy.” He longs to set us free. And once we receive God’s pardon, we begin to experience the power of God’s cleansing work. The past is gone and we start anew. This is called the new birth and it is when we first experience the freedom we have in Christ. Its name alone should tell us how vital this is as a new beginning, a new life. It’s not just a name, though; it’s an actual change. We are born again by the power of God.

New birth is the beginning of the process of sanctification; a process propelled by the means of grace such as prayer, fasting, meditating on Scripture, partaking of Holy Communion, and serving one another in love. A true Christian life should be filled with these opportunities to encounter God’s grace. In the process of sanctification, walking hand and hand with Christ, we learn his ways. For a moment, think of it just as you would any relationship. It takes time to get to know another person. But after spending enough time with someone, you know what that person likes, what they think about things, even some of their better, or lesser qualities. Now apply that to Christ. And unlike a relationship with another person like ourselves —even one we love deeply — Christ has no lesser qualities. He is the very embodiment of perfect love, or as Charles Wesley wrote “pure unbounded love.” To walk with him is to walk with God. And no one who spends time with God remains unchanged.

This walk, or process, enables us to experience what Wesley called Christian perfection. Don’t be frightened by the word “perfect.” The word is used regularly in Scripture such as in the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus commands us to “be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect.” As with any command of Scripture, it is also a promise. God doesn’t just give us commands from on high; he gives us the grace to actually live this way. His commandments are promises of his grace.

But what does Scripture mean by “perfect”? Scriptural perfection is not static as though any change would undermine it; it’s actually dynamic. It is perfection in love (think of that loving father from the parable again) that breaks the power of sin and enables us to live a life of holy love that looks and sounds and is a life shaped by Christ’s own life. The point is to be like Christ, because in him we see God’s vision fulfilled and he wants to see that vision fulfilled in us. Salvation, in so many words, is the freedom to be who God always intended us to be.

The hymns of early Methodism were organized by Wesley in a hymnal to describe this ordering of salvation. The hymnal has a wonderfully long title — very common at the time — A Collection of Hymns for the Use of the People Called Methodists. It was published in 1780 and until the recent publication of Our Great Redeemer’s Praise in 2024, this hymnal was the only truly pan-Wesleyan hymnal, one that the whole family can use.

My doctoral advisor, David Hempton, has said of the 1780 hymnal: “If one were to choose one single artifact of Methodism somehow to capture its essence, the most defensible choice probably would be the ‘Collection of Hymns for the Use of the People Called Methodists.’”

And the hymnal is organized according to the Scripture way of Salvation taught by the early Methodists. We can see in it sections “for those groaning for full salvation,” for “those backsliding,” for those who are walking with Christ and one another in the early Methodist bands (small groups), and for those who have reached perfection in love.

Poetry has a unique way of communicating the faith. And so I leave you with one of Charles Wesley’s hymns from the 1780 collection.

“Saviour of my soul, draw nigh

In mercy haste to me;

At the point of death I lie

And cannot come to thee;

Now thy kind relief afford

The wine and oil of grace pour in;

Good Physician, speak the word

And heal my soul of sin.”

Let us pray for this blessing in our own day, in our churches, our communities, and in our own lives.

Ryan Danker is the publisher of Good News.

by Steve | Jul 22, 2025 | Home Page Hero Slider, In the News, May/June 2025

The Nicene Creed —

By Ryan Danker –

The Nicene Creed, as it is commonly called, is much more than a basic outline of the Christian faith, although it is that. In fact, it is the universal outline of the faith used by Christians everywhere. It can rightly be called the outline of the orthodox faith.

The council that put together the first major sections of our creed met in the year 325 in Asia Minor in a town called Nicaea during the months of May and June. This year, 2025, marks the 1700th anniversary of this lasting statement of Christian belief and so this issue of Good News is dedicated to the creed. Our hope is that faithful believers everywhere not only know the creed, but the Triune God it describes. To know him is everything.

How we acquired the creed is a fascinating story with wonderful twists and turns. At times, the story reads like a novel. In Dan Brown’s blockbuster, The DaVinci Code, Brown uses some of the story correctly because it’s so good, but one thing he got fundamentally wrong was the idea that the Nicene council declared Christ divine at the council. The reality of the situation was that the council affirmed what the church had always taught, but clarified it due to new challenges. Once you know the actual story, though, the creed is much more than an outline. The remains of the battles that necessitated the calling of the council can still be seen in it. The bishops who gathered there 1700 years ago were not only affirming Christian belief, but also guarding it against false claims.

We have to go back into the first centuries of the Christian faith to understand the need for the Nicene Creed. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus changed everything. It was a revolution with cosmic effect that can also be described as an explosion. No one expected the Messiah to rise from the dead in the middle of history. And, in fact, many expected the Messiah to establish a temporal kingdom. Jesus, while fulfilling the prophecies in every respect, blew this away. Not only was his kingdom not of this world, but after he died a sacrificial death, he rose again on the third day, launching the new creation in the middle of history itself. Much of the early church’s discourse is an attempt to grasp this reality.

In the pages of the New Testament, we can see the earliest Christians grappling with the reality of what had taken place in Jesus. There are misunderstandings that needed to be addressed and we can see them in Paul’s letters and in the letters of John, Peter, and Jude, among others. So as the faith continued to expand beyond the earliest followers of Jesus to the far reaches of the Roman Empire and beyond, it needed to continually clarify its message. Once it had become both tolerated and preferred within the Roman Empire under Constantine, the clarity of the church’s message took on even greater importance. This is why Constantine asked the bishops to convene at Nicaea.

But the debate that ignited this meeting didn’t start in Nicaea or with the emperor, but with a popular and charismatic figure named Arius who was a priest in Alexandria, Egypt. The church in Egypt traces its inception to the preaching of Mark, the same who wrote the gospel that bears his name. And so a Christian community had existed in Egypt for many centuries before this time. The church there was intellectually rich, having produced one of the church’s greatest early theological minds in Origen. Egypt was also one of the early birthplaces of monasticism, often linked to the demon-fighting recluse Antony. The church was strong in Egypt and the gospel heard very clearly.

Heresy, the name that the church give false teaching on foundational matters, was first named by the church father Irenaeus. He fought against the Gnostics, a movement that claimed that salvation was given by secret knowledge, often denying the tangible nature of the faith. Heresy is rarely malevolent, though, at least at the beginning. It usually sets in when attempts to describe the mysteries of the faith are taken too far. The description rather than the reveal truth of God takes center stage. And this is what happened with Arius.

Without getting too far into the weeds, Arius accepted the idea that God is immutable (i.e. unchanging) and transcendent. And this is true! God in his nature, his character, his fundamental qualities, does not change. Also, God is beyond comprehension. But Arius took this truth and denied the reality of who Jesus is. If we are to understand the need for the Nicene Creed, to clarify the faith, we must understand that at the center of the entire conversation was the question, “who is Jesus?”

For Arius, if God cannot change and is beyond all things, then God cannot become man. In other words, the incarnation was not “God with us,” but something else. At the same time that Arius wanted to demote Jesus, he didn’t want to claim that Jesus was simply a man. So while God the Father was God, Jesus for Arius was something between God and man, what was called a “demiurge.” In Arius’ teachings, Jesus — or to be accurate to the argument, the Word — was a created being even if God used him to create everything else.

I hope at this point that you have the first chapter of John’s gospel in your mind because it refutes Arius clearly: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” But there are other passages that Arius used to support his argument such as Luke’s mention that Jesus grew in favor with God and with others. Or when Paul calls Jesus the “firstborn of creation.” It’s easy to misinterpret scripture.

Arius, though, was not only a great preacher but he put his teachings to music including a line referring to the Word that still has a ring to it in English “there was a time when he was not.” Arius combined scripture, philosophy, and song to spread his message. And it was hugely popular. In fact, had the church held a poll to see which way its members wanted the council to go, it would have supported Arius.

The bishop of Alexandria, a man named Alexander, opposed the teachings of Arius. But it took another man, Athanasius, to stand up against this popular heresy. His story is fascinating in and of itself. He has sometimes been thought to be short in stature and darker skinned, but it is known that he came from what we might call “the wrong side of the tracks.” He was not of the elite. But he became an educated and forceful figure in the debates. Most of his writings, though, came after the council. He was the council’s great defender.

For Athanasius, following scripture and the teachings of the church, only Christ, fully divine and fully human, could have brought about the salvation of the world by dying on the cross. Only one who is fully God, and therefore capable of such a thing, and fully human, redeeming us as one of us, could have made such an eternal impact.

But let’s get back to the council. The bishops had initially intended to meet in the city of Ankara both to celebrate Constantine’s victory over Licinius and to come to agreement on the date of Easter. But Constantine wanted to be part of the proceedings, so he ordered the bishops to meet in Nicaea, not far from his palace. He also wanted them to clarify the church’s teachings on Christ’s relation to the Father.

Bishops gathered from all over the Christian world, from Spain to Persia. It’s likely that about 200 attended the council. Given the fact that the persecution of Christians had only ended a few years before, some of these bishops arrived with scars and other physical marks of their faith. Neither Arius nor Athanasius spoke at the council. They weren’t bishops, although Athanasius would become one in the years following. The council was organized so that every bishop could speak. Many brought local creeds used in their dioceses, but none of these addressed the fundamental issue that brought them together.

So they turned to scripture as they began to formulate a universal creed. This is why we see language such as “begotten,” “light,” and “Son of God” in the text. But more clarity was needed. So they turned to philosophy and introduced language such as “being” and “substance” in order to describe the scriptural claims of the church. The council used the Greek word homoousion meaning one substance or same being to describe the reality that Jesus and the Father are of the same being, both equally divine. The introduction of this language bothered some as the term is not in scripture, but it was deemed necessary to clarify the faith. In the end, all but 17 of the bishops endorsed the council’s statement, which included calling on Arius to either renounce his teachings or be banished. He chose banishment.

The historian Robert Louis Wilken provides a translation of the original creed of the Nicene council in his book The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity:

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible.

“And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten from the Father, only begotten, that is from the substance of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, through whom all things were made in heaven and one earth; who for us men and our salvation came down and became incarnate, becoming man, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended to the heavens, and will come to judge the living and the dead.

“And in the Holy Spirit.

“Those who say there was a time when he was not, or before he was begotten he was not and that he came from non-being, or from another substance or being, of that he was created, or is capable of moral change or mutable — these the catholic and apostolic Church anathematizes.”

We can see from this text that it is not exactly the same as what we recite in our church services today, but the core is there. Another council, this time in Constantinople in 381, was called to address the Holy Spirit because Arian sympathizers tried to demote the Third Person of the Trinity just as they had tried with the Second. So again, clarity was needed. The creed that we have today is actually the Nicene-Constantinopolitan creed.

It would take many centuries to expunge the teachings of Arius. But the church stood fast. As did Athanasius, who for decades fought against Arians after the Nicene council, being exiled from his diocese numerous times became of his efforts. One of his books, On the Incarnation, became a standard for Christian thought. He was rightly described at one point as Athanasius Contra Mundum, Athanasius against the world. He stood fast.

And the church stood fast, to proclaim the true reality of Christ, the savior, the only one who could be, “God from God, Light from Light, true God of true God.” The only one who could save us. As we mark the 1700th anniversary of the council we can be thankful for the faithful voices who stood firm both then and now. We can also be thankful for the continued guidance of the Holy Spirit in the church. It is right that we mark this milestone anniversary.

Ryan Danker is the publisher of Good News.

by Steve | May 2, 2025 | Home Page Hero Slider, In the News, March/April 2025, Uncategorized

Recurring Patterns & Unheeded Warnings —

By James R. Thobaben (March/April 2025) —

Humans see patterns. It is not enough to see facts, that is, bits of information that correspond to the world around us. It is also necessary to have knowledge, that is an understanding of how those facts fit together. Indeed, to live and thrive, we must also see patterns.

Still, sometimes, we perceive and/or describe patterns incorrectly. This is especially true of historical patterns. There really are patterns that exist and repeat. This is even true about the little corner of humanity describable as Wesleyan-Methodism. Patterns exist. Tendencies are discernable. Probabilities are evident.

One of the most helpful schemas for understanding the history of Methodism is that of Ernst Troeltsch (1865-1923) as modified by H.R. Niebuhr (1894-1962). Troeltsch’s theology is not of very much value to orthodox/orthopraxic believers, but his sociology is. Troeltsch developed the ‘church-sect’ model which was later supplemented by H. Richard Niebuhr, another excellent sociologist who also made dubious theological assertions.

Unfortunately, their sociological arguments are more than a bit “academic-y.” And, these are made even more confusing by Troetsch’s and Niebuhr’s propensity to use very common words like “church,” “sect,” “mystic,” and “denomination” in very narrow and often counter-intuitive senses. For instance, for them “sect” does not mean a closed group of crazed religious extremists, “mystic” does not refer to one who is lost in the adoration of God, nor does “denomination” mean an organized autonomous branch of Protestantism. Even so, their general description of the patterns of church history are very helpful in understanding Methodism.

So, modifying the terms and definitions of the church-sect model just a bit to fit more contemporary language and circumstances, one can divide up Christian Protestant ecclesial organizations using four patterns:

• A state-approved church: An organization that directly cooperates with those holding political and economic power; often the “state-approved church” (in the most extreme form, this is a “theocracy”).

• A sect: An organization in tension with the surrounding society’s power-holders due to the high membership standards that are contrary to the values of the popular culture or, at least, those holding political authority.

• A routinized denomination: An organization with primary focus on maintaining institutional structures and only loose concern with the original mission for which they were created; often there is little expectation of, nor concern for, the local congregation’s membership beyond their financial support ( the word “routinized” means “routine-ized” and often implies an unaccountable bureaucracy).

• An association of syncretistic individuals: A loosely-affiliated group in which members do not necessarily have common beliefs and behaviors; but tensions are minimized by high individualism and low shared expectations.

Although these are ‘ideal types’ or generalized patterns, they are helpful for describing the reoccurring organizational patterns in Methodist history and likely where it will go in the future. Knowing this can help the new expressions of Methodism (perhaps) resist such tendencies and maintain fidelity to the God they claim to serve and the mission for which they first came into existence.

Seeing Historical Patterns in Methodism

At first, Methodist was a “sect” but within a state-sanctioned church. In a sense, it was a Protestant version of a monastic community within Catholicism. The Oxford Methodists (Charles Wesley, William Morgan, and Bob Kirkham, to be joined by John Clayton and George Whitfield, and soon led by Charles’ older brother John) were very strict, holding high membership expectations. They freely chose to be accountable to one another in order to spur one another into living out Christian holiness even while serving as clergy in a broader national church with only nominal membership standards.

Soon enough, these early Methodists — all affiliated with the most elite educational institution in the English-speaking world — began to insist that religious excellence was possible for and expected of all. This claim, and some of their methods (field preaching, visiting the imprisoned, etc.), resulted in significant tension between themselves and ecclesial authorities.

Rejection by their social peers did not impede the early Methodists’ efforts to follow their shared mission of spreading scriptural holiness in “reforming” the nation and the Church (Large Minutes). To the first Methodists this meant offering Christ to any with “a desire to flee the wrath to come” and assisting those born-again to mature in faithfulness. The movement was open to men and women, the rich and the poor, the educated scholar and the day laborer. Methodism grew beyond the founders’ expectations, and it did so quite rapidly. It maintained its sectarian strictness (evidenced by the expulsions noted in the early editions of the “Minutes’’), even while remaining within the state church (the Wesleys and several others remained priests).

The development of formal structures was necessary to maintain both the extremely high membership expectations and significant outreach. In this necessary development of structure — this “routinizing” — lay the insidious kernels of the organization’s spiritual decay. The pattern was set.

Methodism and its revivalism first made its way to the colonies of North America through the ministry of Calvinist Methodist George Whitfield (1740), who allied himself with Jonathan Edwards. The former was the key preacher of the Great Awakening, the North American side of the British Evangelical Awakening that in England and Ireland was being led by the Wesleys. Revivalism in the American colonies lost momentum, in part due to limited organizational follow-up, but Methodism itself picked up again in 1760s under the leadership of committed laypersons. Methodism was still a “sect in a state-sanctioned church” with strict small groups maintaining moral and doctrinal standards.

The American Revolution, though, compelled an organizational change. Some Methodists, and a great number of Anglican priests left for Canada or Great Britian. Those remaining concluded they did not need a state church. Still, the sacraments were a means of grace, Methodists believed an ordained ministry was necessary for consecration. American-based ordination would have to be. The circuit preachers could be ordained, and the strict class and band system would then be maintained by North American lay leadership. Francis Asbury, along with Thomas Coke, (recently sent by Wesley) initiated a new organization, the Methodist Episcopal Church, for this purpose. The “sect-in-state-sanctioned-church” had become a “sect.”

High expectations of members (e.g., regular prayer, mutual accountability, attendance upon the sacraments, regular financial support, and active service to the marginal, including explicit opposition to slavery) once again put the group at odds with some of the newly established political, social, and economic authorities. The sect’s leadership accepted such as inevitable. As Wesley had several decades earlier noted: “Nor do the customs of the world at all hinder [the Methodist from] ‘running the race that is set before him.’ He knows that vice does not lose its nature, though it becomes ever so fashionable…He cannot, therefore, ‘follow’ even ‘a multitude to do evil’” (Character of a Methodist, 1741).

The now unattached sect remained strict for two to three generations. During this time it grew, and grew rapidly (it turns out that people who take Christianity seriously often want to be serious Christians). A huge upswing occurred with the Wilderness Revivals of the first decade of the 19th century (often called the Second Great Awakening, centered at Cane Ridge Meetinghouse in Kentucky). While other congregations were established, it was the strict, revivalist Baptists and even more so Methodists that exploded west of the Appalachians.

Wesley instructed the early Methodists to “[g]ain all you can by honest industry. Use all possible diligence in your calling” (Use of Money). He also realized, long before those sociological thinkers, that this would lead to increased wealth and status and, perhaps, spiritual problems associated not only with materialism but with social “acceptability.”

“I am not afraid that the people called Methodists should ever cease to exist either in Europe or America. But I am afraid lest they should only exist as a dead sect, having the form of religion without the power. And this undoubtedly will be the case unless they hold fast both the doctrine, spirit, and discipline with which they first set out” (“Thoughts on Methodism,” 1787).

By the third and fourth generation Methodists had begun their rise into the new middle class and started to lose their sectarian mutual accountability. This was evidenced in increasing cultural accommodation. For instance, as Asbury bemoaned:

“My spirit was grieved at the conduct of some Methodists, that hire out slaves at public places to the highest bidder, to cut, skin, and starve them; I think such members ought to be dealt with: on the side of oppressors there is law and power, but where is justice and mercy to the poor slaves? what eye will pity, what hand will help, or ear listen to their distresses? I will try if words can be like drawn swords, to pierce the hearts of the owners.” (The Journal of the Rev. Francis Asbury: Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, from August 7, 1771, to December 7, 1815 (New York: N. Bangs and T. Mason, 1821), 2:273)

Along with their economic success and a desire for social acceptance came what could only be called an abomination: the toleration of chattel slavery amongst a wide swath of the membership. The first Book of Discipline (1785) of the Methodist Episcopal Church had required that, “unless they buy them on purpose to free them,” anyone dealing in the trafficking of slaves was, “immediately to be expelled.” Sadly, by the third decade of the 19th century, a bishop owning slaves was tolerated by far too many. Perhaps this was inevitable due to the disregard some fifty years earlier of Richard Allen and Absalom Jones and perhaps 40 laypersons.

The 1830’s toleration of slavery was not the cause, but the proof that Methodism had moved from being a “sect-within-a-state-sanctioned church” through being an independent “sect” to become a “routinized denomination.” Though a debate raged, some denominational elites made excuses for the tacit (or sometimes explicit) approval of the societal convention. Schisms over the moral and doctrinal compromise had already occurred and schism after schism would follow.

Methodism’s willing compromise with the culture seemed to be the inevitable, a sociological pattern. Methodists had become economically successful, the mutual accountability of the band system had gone into decline, and bishops had found pleasure hobnobbing with cultural elites. Methodism did continue to grow in numbers, but also in the social acceptability that coincided with cultural accommodation, in that case over the toleration of slavery.

Schisms over the perceived abandonment of early Methodism’s sectarian fervor occurred. Sometimes this led to a belligerent legalism with the split-off organizations maintaining a small, highly sectarian membership.

There is no reason to rehearse all of Methodist history. The pattern is one that has obviously recurred. Sectarian purity with high membership expectations is modified, rightly or wrongly, for more effective outreach. The organizational structures develop with leadership seeking social approval, and then routinize into unaccountable bureaucracies. Schism after schism occurs in the hope of a “primitive,” Scriptural purity, but then the pattern is reiterated by the third or fourth generation.

Finally, the Methodist movement made it to the late 20th century. In Britain, the pattern of this stage was marked by innumerable abandoned Methodist buildings. In Canada and Australia, Methodism was absorbed into “united” churches, seemingly gaining nothing but more managerial positions. In the U.S. the “mainline” churches — including the United Methodist — were no longer “main.” The oldline denominations, as well as many evangelical ones as well, were deemed mediocre in fulfilling their missions, at best.

Completing the sociological pattern, many of those oldline congregations had become nothing but “associations of syncretistic individuals.” The oldline churches were often made up of people with a shared appreciation for potlucks but having little else in common. Certainly, the “average Methodist congregation” was not theologically or morally consistent. Accountability on personal purity and doctrine for the laity (and, arguably for the clergy and bureaucrats) was gone. “Social holiness,” a term referring to mutual accountability on core doctrine and morality, had come to mean agreement with the bureaucracy’s social agenda.

The historical pattern has been reiterated time after time. Dynamic reformers coalesce in effort to reinvigorate their community. Keeping their original fervor and strictness, they start to grow. They are respected by some for their integrity and rejected by others for their legalism. Small reform groups form internally and a few split off. Paradoxically, the new main body’s social acceptance so compromises its character that it becomes unappealing, and it starts a slow decline. The dissipation is slow at first, because the group has significant social and economic capital which continue to fund the managerial level of the organization.

Can Patterns of Decay Be Resisted?

Does this repeated pattern indicate a sort of sociological predestination? No, but, so what?

• What will happen to the UM Church? In all likelihood, decline continues, especially overseas. Eventually, that will stabilize, perhaps with the societal presence of the UMC being similar to that of the UCC or the PCUSA. A few congregations may remain strong or even grow in small towns or in urban enclaves. Denominational resources that remain will be devoted to organizational maintenance.

Internationally, the UMC brand has not been as damaged as in the US, but it is becoming so. These churches will either decline or split off (the trust clause will be less effectual, though the US funding will remain enticing to bishops and bureaucrats). Lost members will go to growing neo-Pentecostal denominations or become postmodernist non-participants. Some congregations and conferences may become GMC or go autonomous.

There is some hope for those individual UMC congregations that want to remain true to that original mission of the Oxford Methodists. They can survive and thrive, but only to the extent that they operate distinctly from the central administration. Unfortunately, toleration of such by those with organizational authority is unlikely.

• What happens to the GMC? It may become a slightly more conservative version of the UMC. It is likely that rules will quickly arise that limit significant experimentation in order to promote the maintenance of the organization.

Fortunately, this process of routinization is currently being delayed by the stripping down to basics in the new Discipline. Still, it important that the GMC not confuse sectarian theological and moral conservatism with political and cultural conservatism. The goal cannot be to replicate ideals of post-WWII suburban Methodism. If the GMC establishes mechanisms and requirements for mutual accountability for both personal purity and social service, and if it allows experimentations in ministry forms, then it may actually flourish, at least for three or even four generations.

• What happens with the small congregations that have gone independent? They likely become something akin to independent Baptist churches that happen to allow infant baptism. Though there will be exceptions, most will likely function as “family chapels” with strong pastoral care but little concern beyond the walls, so to speak.

• And, what happens with the Foundry Network, the “Collegiate” body, and other very large churches that are not formally affiliating with others? Ironically, as with the very small independents, the lack of accountability beyond the organization may lead to institutional inbreeding. Though their being better at adopting techniques from the popular culture will keep their numbers up at first, they will grow increasingly dependent on the personal charisma of their leadership and an erroneous belief in their own irreplaceability or the spiritual exceptionalism.

The hope for such is that those individual leaders will recognize their need to be accountable, for as Wesley put it “there is no holiness but social holiness.” This includes for those in authority. These churches must demonstrate a genuine willingness to cooperate in ministries, a willingness to participate in outside educational endeavors, and — most importantly — a willingness to be answerable to someone outside the formal congregational structures. Still, if those leaders can direct the church toward expectations of purity (not just numerical growth) and service outreach (not just seeking popularity), then much good ministry can occur (at least until a problematic leader arises).

It is hard to believe any of these groups remaining in or coming out of the UMC will continue to spiritually thrive in their current forms for more than three generations. This is not cynicism, but an acknowledgement that patterns are called patterns because they recur, over and over.

So, in the future, will any offer good ministry, meaning serving the marginal in the Name of our Lord and preaching the Good News to those needing salvation, be offered? Yes, of course, for the glory of God cannot be stopped by human failure. And, there have recently been small expressions of renewal. Perhaps more are coming.

For Methodists to be part, though, they will have to figure out new ways to reiterate the original mission of Methodism and the original mission of the Church. Breaking patterns is hard. And, my suspicion is that these patterns will be sadly replicated.

So, are these “new expressions” following the UMC schism all doomed by a sort of sociological predestination? No. This pattern of rise and decline can be resisted, but I do not see it happening. Then again, I could be wrong.

James Thobaben is Dean of the School of Theology and professor of Bioethics and Social Ethics at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. He is the author of Healthcare Ethics: A Comprehensive Christian Resource. This article appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Good News.

by Steve | May 1, 2025 | Home Page Hero Slider, In the News, March/April 2025

Body Language —

By Jessica LaGrone (March/April 2025) —

The first paying job I ever held was as a Health Aide in a doctor’s office that primarily treated patients and families who were unable to pay for medical care. I wasn’t qualified to do much in the way of real medicine, so one of my main jobs was to call patients in from the waiting room, to take their height and weight and blood pressure, and then to ask them a set of questions to obtain a medical history known as the anamnesis.

Most of us have been through this process so many times that we might be able to reconstruct the questions off the top of our heads:

• What brings you in today?

• How are you feeling?

• Where does it hurt?

• How long have you felt this way?

An anamnesis includes not only our immediate symptoms, but also our family medical history, allergies, questions about alcohol and drug usage and risk-associated behaviors. The result, recorded in a medical chart, sounds a little like a story, a little like a puzzle, a little like a problem to be solved.

But it’s also vitally important to remember that behind each anamnesis is a person, that the symptoms described are not disembodied, but belong to a living soul whose experience of that story feels very, very personal. Can you imagine anything more intimate than the things you experience happening within your own body?

Anamnesis is a Greek word that means “a calling to mind,” or “a remembrance.”

It’s a calling to remember — here specifically a remembrance or a recalling of the experience of one body. But it’s also the medical history going even farther back than that person’s own medical memory.

When I had the job of collecting an anamnesis from each patient I was not yet “in ministry,” but let me tell you that hearing the story of the body feels like holy work. It feels a little like being a priest: hearing confession and helping someone enter into healing.

Years later I found myself on one of those God-prescribed U-turns and began to realize that my calling was not medicine but ministry. One day I was sitting in a seminary class learning about the sacraments of baptism and Holy Communion when the professor began recounting the historic names of the different parts of the eucharistic liturgy: Confession, Absolution, Sursum Corda, Sanctus, Anamnesis, Mysterion, Epiclesis.

I loved learning all of the mysterious-sounding words, but one of them in particular stood out to me. Anamnesis: The remembrance, reenactment, and participation in the history of the Body.

The very same word used by medical professionals to recount the medical history of our bodies was the word used at the Communion Table to recount the holy history of Christ, his ministry, death, and resurrection, which includes his actions and words of institution at the table in the Upper Room: “Take and eat, this is my body, which is given for you.”

I felt like pausing for a moment to send a quick message to my dad, who once told me I was throwing away an undergraduate degree in premedical biology to go into ministry. I thought about telling him: It turns out, they’re basically the same thing! (Aside from the earning potential, anyway.)

Just like an anamnesis in a medical chart follows the journey of a body, an anamnesis at the Table describes the journey of Christ’s body. A holy history of how Christ came to live and die and rise again for us. An anamnesis of love.

In a passage from the first letter to the Corinthians, Paul makes a shocking claim: “Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it” (I Corinthians 12:27).

I can’t imagine a way of addressing someone in any more intimate way than referring to them as one’s own body. Can you?

Nothing is more intimate for us than the experience of our bodies. Our bodies are responsible for all of our input and output to the world around us. They move at our slightest impulse. They provide contact with the world through our senses. Our bodies are both the way we receive input from the world around us, and the way we move outwardly to impact the world around us.

Here Christ is saying: That’s how closely I relate to you, those who believe in me, who follow me. You are my body. You are the way I long to physically and outwardly express my thoughts, my will, my impulses. When I long to touch the world, I touch it through you. When I pour out resources, I do it through you. When I want to share my joy and celebration at the good world I have made, I want to experience and express that through you, my body.

Back in the doctor’s office where I worked, our storeroom held shelves and shelves of medical charts containing the stories of each patient’s symptoms, subsequent diagnoses, and treatments. Some patients had charts so thick that we filled them and had to open up a second chart, and a third, and more, just to hold their story.

Imagine how thick a medical chart would be for a 100-year-old patient. What if a patient could be more than a millennium old? Two millennia old? How long would their story stretch?

Imagine, if you will, that patient’s anamnesis:

The patient is a 2000-year-old who presents with both acute pain and rampant disease, but also a remarkable capacity for healing and resilience. She has been through a multitude of cancers, amputations, and treatments, but also astonishing recoveries.

Her greatest scars include the Crusades, her silence during the Holocaust, her complicities to slavery and injustice and abuse. Some of these diseases are so disfiguring those closest to her would say she doesn’t even look like herself.

She has been through many treatments, recoveries, and regenerations, often stirring from the point of near death. Sometimes it seems that she is in a coma, or on life support, but that’s usually when she is revived somewhere it is least expected.

Without her, our laws would have no foundation, our societies would lack moral guidance, purpose, and hope. Without her we would miss the depths of compassion brought through her works in hospitals and schools and missions. Through her diseases have been cured, orphans taken in and raised. Countless lonely people in her have found family and purpose and strength.

Because this body is always shifting and growing, it’s difficult to find ways to describe her physical anatomy. What exactly is her height, weight, mass? Is her temperature hot or cold or lukewarm? Is her heartbeat racing or slowed to a flat line?

It’s hard to say what should go in her chart under physical characteristics. Is she a tiny country church up on a hill or a mega-church auditorium? Is she shouting or meditating, dancing or repeating liturgy? Is she gathered under trees, in tents, in cathedrals or auditoriums, at schools or in homes? Is she in schism or in unity? Marching in protest or in bowing in deep contemplative silence?

When we try to picture her some of our feelings are warm and nostalgic, others are pockmarked with trauma or pain. “Church hurt” is a diagnosis repeated all too often these days.

Being part of a body can be both painful and healing. When a physical body has encountered an illness or pathogen, it develops antibodies that are specifically targeted, specifically shaped, to take down those challenges the next time it faces them. It’s the reason I won’t have chicken pox again — my body still carries the antibodies it made when I was nine.

One of the miraculous things about being a member of a body that has existed over 2000 years is that there is very little we can experience today that it hasn’t gone through in some way before. If we are paying attention to the incredible connectivity to the history of this body, we may find many of our diagnoses are not new at all. If we search our chart we may also find treatments there that help.

Scripture can inoculate us against individualism. The Psalms can give us a booster of lament and praise and anger and repentance and joy. Liturgy and history swirl within us, bringing nourishment and reminders that this is not the first time the church has faced challenges.

Church history carries in its bloodstream stories like Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s, who knew the Church during some of her darkest days of sickness. Surrounded by evidence of disease, he still worked to build a new kind of Church that stood on conviction, even when it meant losing his own life to save hers.

Perhaps when we encounter the dizzying effects of nationalism, or the painful symptoms of tyrants and conflicts and wars, pieces of the past will rush at us like white blood cells ready to fight again the very things that threatened before and threaten again.

In the last few years it seems like story after story has broken with news of leaders of the church inflicting harm on the body through misconduct and abuse.

Recently when one of these horrifying scandals broke, a preacher close to the events used his platform to offer those at the center of pain the metaphor from scripture of Lot’s wife, telling those facing a church torn apart by abuse not to turn back, not to dwell on the past, but to continue moving forward in faith.

Whatever his intentions, many heard it as a call not to reveal or process the wounds laid bare by the scandal that had broken only days before. Unfortunately, his message brought more pain to those already hurting. It was heard as a call to silence the heartbroken rather than facing an honest and open counting of the cost, lest the Church be hurt by the stories that might be told.

If I learned anything in the patient intake room long ago, it’s that the telling of the story of pain is part of the healing. Until the body bears witness, tells its whole story of hurt and grief, there is no chance for true healing. That’s what an anamnesis is — to tell the story of the body so that help and healing and intervention can rush in to the areas that need it the most.

To tell the truth is the beginning of getting the help we need. But to hide a wound means risking that it will fester to the point of infection, dismemberment and ultimately loss. If we want to heal, we will tell the stories of the body, even those that make us flinch.

I sometimes talk to young people who have experienced so much pain as they’ve witnessed the flaws of the Church that it makes them want to withdraw into a little corner of the faith. They haven’t given up on Jesus, just the people with the keys to his house.

Sometimes they wonder if they could leave all the trappings behind and start over. As one of them told me recently: “I don’t know if I can bear the Church, but I think I could do just Jesus and me and a few friends.”

“Well,” I said, “then you’ve just started the Church all over again!”

For those who want to authentically follow Jesus, amputation is not an option. We can’t do it alone. Christians need Christians. Churches need churches. Our medical history would urge us not to let the moments of struggle drive us away from the place that healing can happen. Amputation has never gone well for the limb.

There are no single-celled Christians. No healthy single-celled churches. Bodies need connective tissue to survive.

In Communion, the anamnesis, finds its climax in these words: “On the night he was betrayed and gave himself up for us, Jesus took bread, blessed it, broke it and said: ‘This is my body, given for you.’”