by Steve | Apr 26, 2022 | Home Page Hero Slider, In the News, May-June 2022

By Rob Renfroe

By Rob Renfroe

When I speak to churches about the problems dividing the United Methodist Church, I begin by saying, “If you are not aware of what I am about to tell you, it will be hard for you to believe. I’ll sound like an ancient astronomer trying to convince you the earth revolves around the sun when everyone is certain it’s the other way around. I’ll come across like the ‘lunatic’ of an earlier era proclaiming the world is round when everyone ‘knows’ it’s flat. Some things are hard to believe even though they are true.”

Then I describe to them the deeper issues that divide the UM Church. I tell them we are divided about the Bible. Over the years, there have been UM pastors who’ve made statements about how the Bible cannot be trusted to tell us God’s will and how they scoff at those of us who believe the Scriptures are the inspired word of God. I recount our differences about the work of the Holy Spirit and how many UM pastors have told me the Spirit is revealing new truths that contradict and override what the Bible teaches.

I tell them about my conversation with a highly respected tall-steeple pastor who told me, “Rob, the Church created the Bible. So, we can re-create the Bible.” I tell them that worst of all we are divided on Jesus. Some of us believe Jesus is the way, the truth, and the life for all humankind. But we have a bishop who has warned us not to make an idol (a false God) out of Jesus. We have a UM seminary professor who told me, “God is wholesale; Jesus is retail,” meaning Jesus is just one of many religious teachers, not really different from Mohammad or Buddha. We had a UM seminary president who said if you feel a need to tell persons of other religions about Jesus, you don’t understand Jesus.

These are hard things to believe if you have been in your local church with a pastor who is faithful to the Scriptures, where you repeat the historic creeds and mean them, and where you pray for your nonbelieving neighbors to come to faith in Jesus. These are hard things to believe, but they are true.

Now, there is another hard truth we must accept. The Commission on General Conference delayed General Conference for political reasons. The Commission did not simply disappoint us by deciding not to hold General Conference. They chose not to hold General Conference and they chose not to do the work that could have made it possible.

Trusted members of the Commission report that the international delegates who spoke up during the deliberations concerning General Conference argued that it could be held and that delegates from around the world could find a way to travel to the United States. Those who argued otherwise were primarily white, American, and liberal (see article on page 16).

It’s hard to believe that a desire to sabotage the Protocol of Grace and Reconciliation through Separation was the reason many Commission members voted against holding General Conference. But it’s even harder not to. The Episcopal Church, the Lambeth Conference of Bishops, the United Methodist Women, and the Wesleyan Covenant Association are all holding large in-person meetings this spring and summer with delegates coming from around the world.

Where there is a will to meet there is a way. Where there is a will to undermine the one solution that would have led to a just and orderly resolution of the problems that divide us – well, the institutional members of the Commission found a way. Ironically, the Commission announced at its March meeting the formation of a task force to explore the possibility of a hybrid General Conference in 2024. This change of heart comes too late and shows what the Commission thought impossible could have been done a year ago.

Again, I know that’s hard to believe for persons in their local churches who assume all church leaders are honest, fair, and well-meaning. But the truth is the earth revolves around the sun, the world is round, and power politics led to the postponement of General Conference.

Here’s something else that will be hard to believe. There will be some bishops who will mislead the church and many pastors who will deceive their congregations in the coming months about the future of the UM Church. As local churches consider their options for leaving, they will be told they are overreacting. Some bishops and pastors will tell United Methodists in the pews that “there is no reason to depart because nothing will change – the UM Church will continue to be a big tent denomination that respects all persons and all points of views. You and your church will never be made to do anything you do not want to do.” If it’s hard for you to hear this, I’m sorry. But statements claiming there will be no change in the local church are untrue. And many who say these things know they are.

If you believe the progressives (who will be in control of the denomination when many traditionalists leave) will allow you to deny “justice” to same-sex couples who want to be married in your church; if you believe liberals will permit your annual conference to discriminate against partnered gay persons who feel called to be pastors; if you believe a bishop will never send a progressive pastor to your congregation to make you into “a real Methodist church,” then you are in denial.

The progressives have told us who they are. They have been open about their agenda. And after the Commission’s decision to cancel a General Conference that could have allowed us to go our separate ways in peace, it is obvious that some church leaders will do anything necessary to reach their goal of a woke liberal denomination, even if it means harming traditional churches.

It’s time to believe hard things. And it’s time to do a hard thing: Prayerfully consider leaving the UM Church. I hope you and your congregation will join other traditional Wesleyans in the Global Methodist Church. It may take time to do that. We have hard decisions in front of us. My prayer is that traditionalists will step into a better day with others who believe in the Lordship of Jesus, the truth of the Scriptures and the transforming work of the Holy Spirit.

Rob Renfroe is the president and publisher of Good News.

by Steve | Apr 22, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

The United Methodist Church is currently in an extremely awkward position. The vast majority of church leaders acknowledge the need for separation to take place in order to resolve the decades-long controversy over biblical authority and interpretation, sexual ethics, and the definition of marriage (among other topics). A Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation was negotiated and appeared to have broad support across the church in 2020. The pandemic has interfered, causing the postponement of the 2020 General Conference, which was set to potentially adopt the Protocol. Now, the General Conference will not meet until 2024.

There is now no clear, denomination-wide process for local churches to disaffiliate from the UM Church in order to align with the Global Methodist Church. We thought by adopting ¶ 2553 (the Taylor disaffiliation plan) in 2019, that the General Conference had created such a consistent process. However, the way ¶ 2553 is being applied, every annual conference can make its own rules about what is required for a local church to move to the GM Church. In effect, there are 50 different sets of rules in the United States for local churches to follow. And the various annual conferences outside the U.S. are in different situations, operating under their own sets of rules and legalities.

In the absence of a clear, denomination-wide process for disaffiliation, many traditionalists are feeling “stuck” in a denomination that has abandoned what they believe and stand for, particularly in the U.S. It is important to understand the factors creating this “stuck” feeling and to move toward addressing the causes. Only as an amicable separation is able to take place will The United Methodist Church, as a whole and all its parts, be able to move forward into a new and more faithful reality (regardless of which perspective people hold on our issues of disagreement).

Lack of Information

One of the factors in a feeling of “stuckness” is the lack of information being shared. Many average church members have been unaware of the depth of the division within the UM Church. Many clergy have bent over backwards not to tell them what has been going on. With the announcement that the Global Methodist Church is launching, there are many laity saying, “Wait – what?!” It is important for clergy and lay leaders in local churches to inform their people about the issues dividing our denomination and the potential for separation. Being kept in the dark creates feelings of powerlessness and mistrust among members toward their leaders.

Information is available on the Good News website and on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website that delves into the issues around separation. Most of my articles are collected on my blog site for people to read, and they cover the issues involved over the past several years.

Even more problematic is the lack of information about the process of separation for local churches. Once a church wants to explore its options, those options must be explained in a way that allows for church leaders and congregations to make informed decisions. UM News Service has a comprehensive article that helps understand the process of disaffiliation in general. Wespath (the church’s pension board) has prepared information about disaffiliation and how it affects clergy and congregations in relation to the pension program. Other general information about disaffiliation is available on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website, including information about the Global Methodist Church, for which you can also see the GM Church website.

This is all good general information, but the problem I mentioned above is that there are different rules for disaffiliation for each annual conference. Many annual conferences have not published their unique rules or made them available even on request. In some annual conferences, repeated calls to the conference office go unreturned. Again, where people are kept in the dark, they feel helpless and “stuck.”

One important piece of information is how much money a church would owe in order to disaffiliate. Under the prevailing rules of ¶ 2553 enacted in 2019, a church must pay two years’ worth of apportionments and its share of the annual conference’s unfunded pension liability. That pension liability payment is calculated individually for each congregation by its annual conference. Yet, many annual conferences are not making that payment amount available to congregations, even when they request it.

The North Georgia Annual Conference has taken the lead by publishing that pension liability payment for each local church on its website. An annual conference receives its pension liability number from Wespath each year in the fall. It can then allocate the local church’s share of that pension liability using a formula determined by the annual conference. Most often, this is the apportionment formula, but various annual conferences use different formulas to calculate the individual congregation’s share.

It is unfortunate that many annual conferences are refusing to make that number available to their local churches in a timely way when they request it. This is a simple math problem. The number for all local churches in an annual conference could be calculated in an afternoon. Yet, some conferences are holding on to that information and keeping their churches in the dark. The local church is then “stuck” because it cannot move forward toward making a decision on disaffiliation without knowing how much it is going to cost.

Delay

Another factor in causing the feeling of “stuckness” among traditionalists is that some bishops and annual conferences are refusing to move forward with the disaffiliation process, even though it is outlined in the Book of Discipline. Several annual conferences are not moving forward with disaffiliations this year because they have yet to figure out their rules to govern the process. This is despite the fact that ¶ 2553 has been the law of the church since 2019. At the very least, this situation betrays the level of incompetence among some annual conference leaders in failing to consider and develop plans in a timely way for local churches to disaffiliate. (One hope for the Global Methodist Church is that it will be much more nimble, able to respond to changing circumstances rapidly and anticipating needs and planning for them ahead of time.)

A more nefarious motivation may be behind some delay tactics. Some annual conference leaders may be hoping to make the process so long and torturous that local churches give up and remain within the UM Church. One district superintendent responded to a request for disaffiliation from a local church by saying that his district already had several churches disaffiliating this year and he did not have time to deal with more. So this church would just have to wait until next year. Other superintendents have refused to schedule a church conference to vote on disaffiliation when requested to do so by the local church. After all, the longer it takes a church to disaffiliate, the longer that church will contribute its apportionments to support the annual conference. Of course, that assumes congregations will be willing to continue paying apportionments in the face of what appears to be bad faith actions.

The failure of some annual conferences to draft the rules for local church disaffiliation can fall under this delay category, as well. Some annual conferences are saying, “Sorry, we have to draw up the rules and then they have to be approved by this year’s annual conference in order to take effect. You will have to wait until next year to disaffiliate.” Again, conferences have had three years to draw up their rules for disaffiliation, and the failure to do so, even amid the pandemic, is inexcusable. Some conferences are finding a way to work around this by holding a special annual conference session later in the year to deal with disaffiliating congregations. Others could do the same.

These delay tactics will not cause traditionalists to want to remain United Methodist. If anything, they will reinforce traditionalists’ desire to move into a new denomination that is more responsive and provides better leadership. Unfortunately, some traditionalists will not be willing to wait for the annual conference to get its act together. Individual members may just decide to give up and go down the road to another denomination’s church that is in line with their beliefs. That will, of course, weaken the traditionalist UM congregation. It also plays into the hands of the annual conference, which could then potentially send in a liberal pastor to shift the congregation in a more theologically progressive direction, hoping to keep it in the UM Church. Or, if the church declines too much, the conference will just close the church, sell the property, and live longer off the legacy of resources accumulated by traditionalist congregations.

In any event, the delay makes that congregation feel “stuck.” It cannot move forward because of the roadblocks put up by its annual conference.

Egregious Financial Payments

A final factor in keeping traditionalists feeling “stuck” is the imposition of egregious financial payments on a disaffiliating congregation. The requirements of ¶ 2553 amount to roughly six to nine times the congregation’s annual apportionment figure. Many churches find it challenging to raise that amount of money in a lump sum to be paid at the time of disaffiliation. Some congregations resort to borrowing the funds from a bank, from the UM Foundation, or from their members. Of course, that imposes a long-term drag on the church’s ability to fund ministry, but at least it gets them into a more desirable denominational situation. But if they cannot raise the funds or are unwilling to pay that amount, they will be stuck.

On top of that already challenging financial payment, some annual conferences are requiring local churches to pay additional costs. Most egregiously, some are charging a percentage of the church’s appraised property value (anywhere from 20 to 50 percent). One conference is even trying to get 50 percent of all the church’s assets, including mission funds, local foundation, memorial funds, etc.

Essentially, these annual conferences want their disaffiliating congregations to pay twice for the facilities they will carry into the new denomination. In many cases, those congregations have been faithfully paying into the conference apportionments and program for decades, and the annual conference has put none of its own money into those congregations. To charge congregations for a percentage of their facilities is grossly unfair and amounts to a “poison pill” that effectively prevents a congregation from departing. For most churches, there is no way for them to raise the kind of money that would double purchase their buildings and assets.

These egregious financial payments again make traditionalists feel “stuck” and unable to change their congregation’s denominational alignment.

The Consequences of “Stuckness”

To the extent that UM leaders are pursuing a strategy to slow-walk disaffiliation in hopes of keeping traditionalists “stuck,” it is a strategy that could backfire. Weakening local churches serves neither the interests of the UM Church nor the GM Church. Nor does it advance the work of God’s Kingdom.

Keeping unwilling traditionalists boxed into the UM Church only increases resentment toward the denomination and jeopardizes continued apportionment payments and other forms of participation and engagement in the work of the church. It also prevents centrists and progressives from moving forward with their agenda to change the UM Church in a more progressive direction. Instead, it is in the interest of centrists and progressives to allow traditionalists a clear and feasible pathway to disaffiliate. Only as congregations are sorted out to where they want to be will both denominations be able to put the conflict behind them and move forward into a positive future. Here’s to hoping that the “stuckness” ends soon!

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo by Shutterstock.

by Steve | Apr 21, 2022 | In the News

Lloyd J. Lunceford

Church Trust Law Webinar: Tuesday, May 10, 7 PM Central Time

***

Do United Methodist congregations own their buildings?

What is a trust?

Can the United Methodist trust be revoked?

Is there a legal process for disaffiliating from the UM Church separate from what is in the Book of Discipline?

When might it make sense to use the legal process, rather than the Discipline’s process?

When might a local church need an attorney, and when might it not need one?

What steps should a local church take to prepare for disaffiliation?

During this confusing time in The United Methodist Church, it is important to have clear, factual answers to the many questions surrounding disaffiliation. Good News is sponsoring a Webinar to help answer these and other questions and provide helpful information. Understanding church trust law can help your church discern when it is appropriate to use an attorney and when it is not needed.

The presenter will be Lloyd Lunceford, Esq. of the firm Taylor Porter in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He has practiced law since 1984, with emphases in higher education, mass communications, commercial litigation, and church property laws. He served for many years on the board of the Presbyterian Lay Committee, the Presbyterian equivalent of Good News. He was involved in many church property cases during the separation of the Presbyterian Church (USA) and has a wealth of knowledge and experience in this area. You can read more about him at https://www.taylorporter.com/our-attorneys/lloyd-j-lunceford

To participate in the webinar, please use this Zoom link below:

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/89831892524?pwd=ZEpNZzFxWm5GcUdCR05BVlh5V0p5Zz09

Meeting ID: 898 3189 2524

Passcode: 869881

If you have any questions, please contact the Rev. Tom Lambrecht at tlambrecht@goodnewsmag.org

by Steve | Apr 15, 2022 | In the News

By Shannon Vowell

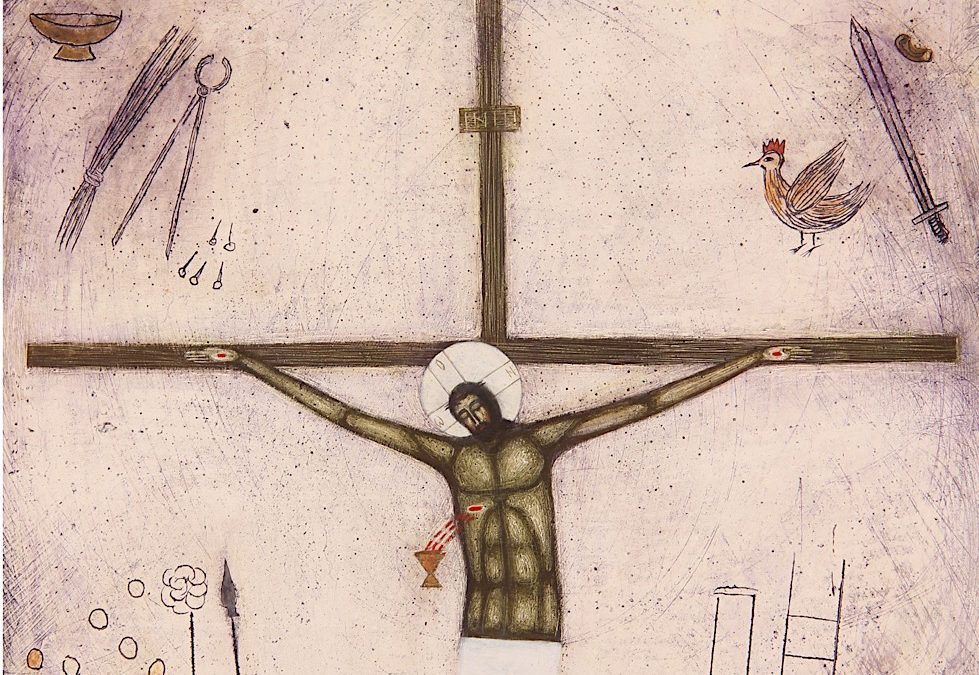

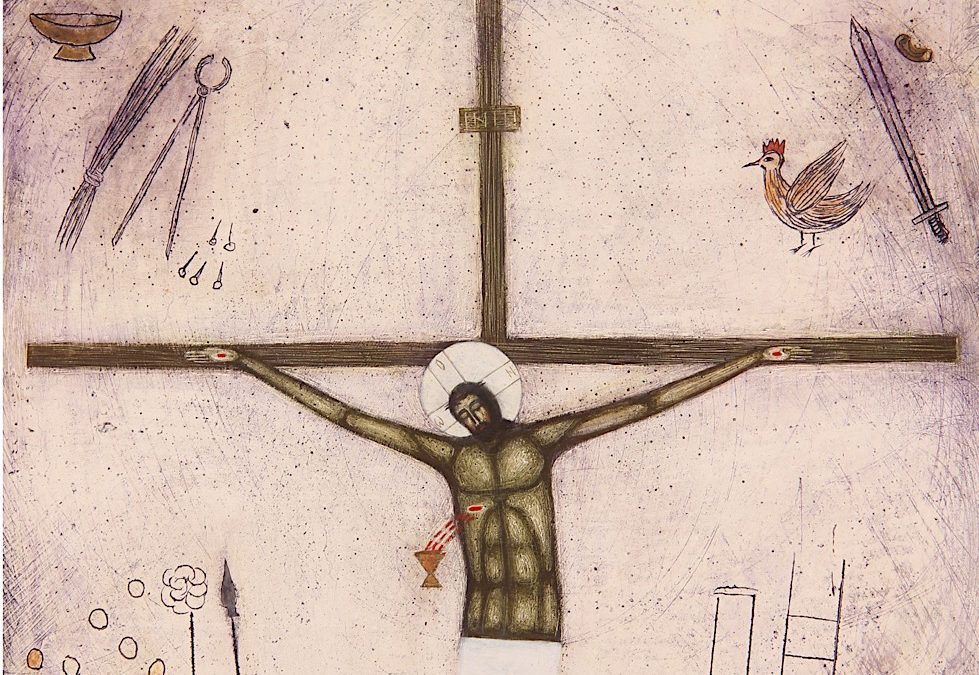

Sunrise that day:

Your own Creation displaying glory.

But no joy for You;

You stumbled, pain-wracked, through the story

To see it to its bitter end,

To see it through…

No hope, no friend

Could there attend You as You faced

What no one else could face:

The whole weight, reek, waste, and grief of the human race;

Sin itself put on You, the sinless One…

Father, Spirit, separated from suffering Son…

How did You persevere?

What kept You there – displayed, a broken thing,

As if You were NOT God? Not Lord? Not King?

What held You to that Cross through hours that lasted years –

Straining to contain the centuries’ mass of murders, lies, greed, fears?

Why did You choose to die one Friday afternoon –

You, Who created time itself?

Was there no other way

To wipe the slate clean, ransom all the slaves,

Than living every moment of that Hellish day

And then living Hell itself?

All, all for us – that we might truly say,

“My Savior” –

Pray,

“Our Father” –

Stay

With You, Immanuel,

Through all eternity …

I cannot see how we were worth Your agony.

But Your love declared it so

And You are the Truth

You are “I Am”

Logos. Lord.

Perfect,

slaughtered,

Lamb.

O Jesus, grant us sight today to see Your bleeding body

as Your gift

Of life to us,

the beggars that You lift

From muck and mire to holiness and peace.

O Jesus, give us breath to praise and faith to claim:

Your love

will

never

cease.

Shannon Vowell, a frequent contributor to Good News, blogs at shannonvowell.com. She is the author of Beginning Again: Discovering and Delighting in God’s Plan for Your Future available on Amazon. Art from Natalya Rusetska of Lviv, Ukraine. Special thanks to iconart-gallery.com

by Steve | Apr 14, 2022 | In the News

By George Mitrovich

Good News, May/June 2005

Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The presentation of the Gold Medal to Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, took place at a 90-minute ceremony on March 2, 2005, in the great rotunda of the United States Capitol.

Jackie Robinson was a Hall of Fame baseball player. But the Gold Medal isn’t given for athletic achievement – Robinson was a four-sports star at UCLA, and some believe baseball was not his best sport – but in recognition of one’s achievements as a human being.

In becoming the first black man to play in the major leagues, Robinson encountered racism in its vilest manifestations – racial taunts and slurs, insults on the playing field and off, character assassination, death threats, and anything else the wicked among us in mid-twentieth century America could throw at him. But despite the evil of such provocations he somehow found a way to rise above his tormentors, to literally turn the other cheek and demonstrate that however great his athletic skills, his qualities as a human being were infinitely greater.

When the time approached for Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Dodgers to sign Robinson, he had several difficult decisions to make. First, should he sign a black player? And if he did, what were the consequences? Second, did Robinson have the talent to play in the big leagues? Third, was he tough enough in the best sense to confront the certain racial turmoil he would face?

Rickey was a man of exceptional intelligence and ability. He was known throughout baseball as “the Mahatma” for his great wisdom (more than any other person he was responsible for creating baseball’s farm system, key factors in his success with the St. Louis Cardinals and later with the Dodgers in Brooklyn).

The assurance Rickey sought as to Robinson’s character was found in Jackie’s boyhood, growing up in Pasadena, California (he was born in Cairo, Georgia, the son of share croppers, and the grandson of slaves). In his youth Jackie came under the influence of a young minister in Pasadena. His name was Karl Everitt Downs, the 25-year old pastor at Scott Methodist Church where Jackie’s mother, Mallie, worshipped.

The story of Downs and Robinson is brilliantly told in Arnold Rampersad’s biography Jackie Robinson (Alfred A. Knopf, 1997).

Rampersad, dean of the humanities department at Stanford University, writes that Downs went looking for Robinson. He found a group of Jackie’s friends loitering on a street corner. He asked for Robinson, but no one answered. He left a message, “Tell him I want to see him at junior church.” Sometime later, Rampersad writes, “Jack delivered himself to the church and began a relationship that lasted only a few years, but changed the course of his life.”

Rampersad continues the story: “To Downs, Robinson evidently was someone special who had to be rescued from himself (Jackie had had some run-ins with the Pasadena police) and the traps of Jim Crow.” One of Jackie’s friends said, “I’m not sure what would have happened to Jack if he had never met Reverend Downs.”

“Downs led Jack back to Christ,” the author writes. “Under the minister’s influence, Jack not only returned to church, but also saw its true significance for the first time; he started to teach Sunday school. After punishing football games on Saturday, Jack admitted, he yearned to sleep late: ‘But no matter how terrible I felt, I had to get up. It was impossible to shirk duty when Karl Downs was involved. … Karl Downs had the ability to communicate with you spiritually,’ Jack declared, ‘and at the same time he was fun to be with. He participated with us in our sports. Most importantly, he knew how to listen. Often when I was deeply concerned about personal crises, I went to him.’

“Downs became a conduit through which Mallie’s message of religion and hope finally flowed into Jack’s consciousness and was fully accepted there. … Faith in God then began to register in him as both a mysterious force, beyond his comprehension, and as a pragmatic way to negotiate the world. A measure of emotional and spiritual poise such as he had never known at last entered his life.”

Robinson himself would say, “I had a lot of faith in God. … There’s nothing like faith in God to help a fellow who gets booted around once in a while.”

The influence of his mother, Mallie, and his pastor, Karl Downs, would forever affect the way Jackie Robinson lived his life, how he saw other people, and how he coped with discrimination. He had been taught that he was a child of God, and no one and no challenge, however brutal and dehumanizing, could take that away from him.

Why did Rickey find those experiences of the young Jackie so persuasive? Branch Rickey was also a Methodist. Not just a Methodist, but, according to Rampersad, “a dedicated, Bible-loving Christian who refused to attend games on Sunday.” His full name was Wesley Branch Rickey. He was a graduate of Ohio Wesleyan University – and the influence of the Methodist Church was a great factor in his life.

In Rampersad’s chapter on Jackie’s signing with the Dodgers – “A Monarch in the Negro Leagues (1944-1946)” – he tells the dramatic story of a meeting that took place in the late summer of 1945. The meeting was held on the fourth floor of an office building at 215 Montague Street in Brooklyn. In that meeting were Branch Rickey and a Dodger scout by the name of Clyde Sukeforth, who had been following Robinson with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues.

“Rickey made clear that Jack’s ability to run, throw, and hit was only one part of the challenge,” Rampersad wrote. “Could he stand up to the physical, verbal, and psychological abuse that was bound to come? ‘I know you’re a good ball player,’ Rickey barked. ‘What I don’t know is whether you have the guts?’

“Jack started to answer hotly in defense of his manhood, when Rickey explained, ‘I’m looking for a ball player with guts enough not to fight back.’

“Caught up now in the drama, Rickey stripped off his coat and enacted out a variety of parts that portrayed examples of an offended Jim Crow. Now he was a white hotel clerk rudely refusing Jack accommodations; now a supercilious white waiter in a restaurant; now a brutish railroad conductor, he became a foul-mouthed opponent, Jack recalled, talking about ‘my race, my parents, in language that was almost unendurable.’ Now he was a vengeful base runner, vindictive spikes flashing in the sun, sliding into Jack’s black flesh – ‘How do you like that, n—-r boy?’ At one point he swung his pudgy fist at Jack’s head. Above all, he insisted, Jack could not strike back. He could not explode in righteous indignation; only then would this experiment be likely to succeed, and other black men would follow in Robinson’s footsteps.

“Turning the other cheek, Rickey would have him remember, was not proverbial wisdom, but the law of the New Testament. As one Methodist believer to another, Rickey offered Jack an English translation of Giovanni Papini’s Life of Christ and pointed to a passage quoting the words of Jesus – what Papini called ‘the most stupefying of His revolutionary teachings’: ‘Ye have heard that it hath been said, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil: But whosoever shall smite thee on thy right check, turn to him the other also. And if a man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.’”

Many years later the Houston Chronicle told its readers a wonderful story about the two men fated to change baseball and race relations in America:

“Before Rickey’s death in 1965 at age 83, he sent a telegram to Robinson, who by that time was retired from baseball and involved in the Civil Rights movement with Martin Luther King Jr.

“Wheelchair bound and suffering from a heart condition, Rickey apologized to Robinson for not joining him at the march on Selma, Alabama.

“Robinson responded with a letter that read, in part: ‘Mr. Rickey, things have been very rewarding for me. But had it not been for you, nothing would be possible. Even though I don’t write to you much, you are always on my mind. We feel so very close to you and I am sure you know our love and admiration is sincere and dedicated. Please take care of yourself.’”

Through his on-the-field skills as a player and his off-the-field personal attributes, Jackie Robinson became an enduring symbol to black men and women across America – creating hope, raising their expectations, giving them faith that maybe, just maybe, the promise of American democracy that all men are created equal might become something more than words on a historic document. Eloquent words, yes; lovely words, yes; ennobling words, yes; but absent their reality that in the everyday lives of black Americans, they would remain that and nothing more – mere words.

And thus the presentation of the Gold Medal was given to remind all Americans of the significance of Jackie Robinson, to affirm his place as an individual who changed, not just a sport, the game of baseball, but more importantly the social and political dynamic of our nation’s life – and change it for the better. Indeed, with the exception of Martin Luther King Jr., Jackie Robinson was probably the most important black man in twentieth century America.

No one has made this point more convincingly than Buck O’Neil, chairman of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. O’Neil, whose own story as a black player has brought him national acclaim – he was the star of Ken Burns’ award winning baseball series on PBS – has pointed out that before President Truman desegregated the military, before the bus boycott in Birmingham, before the civil rights marches in the South, before Rosa Parks, before Brown v. Board of Education, and before anyone had ever heard of Martin Luther King Jr., there was Jackie Robinson.

Dr. King himself eloquently said of Jackie, “Back in the days when integration wasn’t fashionable, he understood the trauma and humiliation and the loneliness which comes with being a pilgrim walking the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.”

“The word for Jackie Robinson is ‘unconquerable,’” Red Smith, the great sports writer would say. “He would not be defeated. Not by the other team and not by life.”

The first Congressional Gold Medal was given to George Washington. Now one belongs to Jackie Robinson. One of these men was the father of our country, the other an athlete who tore down signs that read, “Whites only.” You can’t explain our history as a nation without understanding something about George Washington; neither can you explain it now without understanding something about Jackie Robinson. In a land that strives to exemplify both freedom and equality, they are forever bound as equals – recipients of the Congressional Gold Medal.

Thirty-three years after Jackie died, the Gold Medal ceremony took place in the Capitol of the United States; in a place some have called, “The Cathedral of Democracy.” It was a lovely day for America. The dream lives on.

George Mitrovich (1935-2019) was a frequent contributor to Good News, a lifelong member of First United Methodist Church in San Diego, and active in Wesleyan renewal efforts. He was president of The City Club of San Diego and The Denver Forum, two leading American public forums. For more than two years he played a key role in working with the Boston Red Sox, Congress, and the White House to obtain for Jackie Robinson the Congressional Gold Medal. The Family of Jackie Robinson has thanked him for his efforts and for having initiated the process that led to the presentation of the honor. This article first appeared in the May/June 2005 issue of Good News.

By Rob Renfroe

By Rob Renfroe