A Divine Moment for Gen Z

Each historical move of God is unique. “The wind blows where it wishes,” said Jesus. With so many other onlookers, we have been prayerfully mindful of the student-led renewal and revival services taking place since February 8 on the campuses of Asbury University and Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. From all reports, students are encountering the Living God.

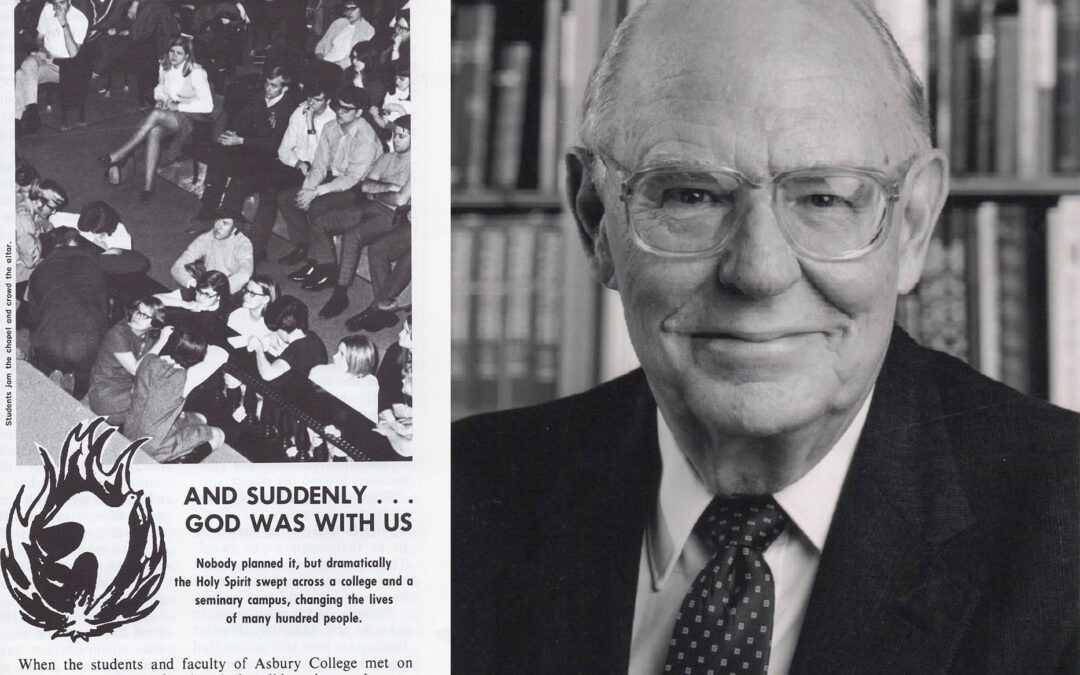

For several decades, Good News was headquartered in Wilmore. In 1970, Dr. Dennis Kinlaw was the president of then-Asbury College. At the time, the school was the epicenter of a powerful outpouring of the Spirit among the college students. “The young people in this movement have been the key,” Dr. Kinlaw wrote in Good News magazine more than 50 years ago. “Faculty and administrators have been chauffeurs and guides while the Spirit has used the young to open closed doors and storm the enemy’s bastions.”

Decades later, the same could be said of the spiritual stirring on campus in Wilmore. Facebook and other social media outlets have publicized the events in Hughes Auditorium to a worldwide audience. There are no celebrity personalities or “influencers” at the helm of this organic movement – only students and a very capable campus administration. We have pulled together a non-exhaustive collection of excerpts, quotes, and observations from special voices – undergrads to PhDs – to share in this Perspective to give insight, encouragement, and context.

Sarah Thomas Baldwin, Vice President of Student Life and Dean of Students, Asbury University (Facebook)

Last Wednesday, February 8, at 11:00 a.m., the Holy Spirit filled Hughes Auditorium (our chapel) and has not let up. Again and again, people report experiencing God like they never have before in their lives.

Early on, thick clouds came down and settled around our campus. I will never forget how it seemed to be the visible thick presence of Jesus settling in on us.

The movement of God is across the generations – from 93 years old to 2 weeks old – they have shown up. College students arriving with backpacks and pillows, wheelchairs and elderly people, babies in strollers, in arms and in front packs. Children and many teenagers. And of course, at the heart – Gen Z.

The Holy Spirit lit the wick of Gen Z, and now people from around the nation are putting their candle into the fire, experiencing the goodness and grace of God.

Many testimonies from college students about release from anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation. Come Lord Jesus! This generation needs this.

Words that people keep saying to me about their experience: LOVE of God, JOY of Jesus – “I have never experienced this! I have never felt Jesus like this!” I hear this all day every day for 7 days. …

Afternoon testimony time! Hearing people testify to the goodness of God with incredible testimonies often about freedom from addiction, healing of relationships, a word of blessing proclaimed. …

Alexandra Presta, editor, Asbury Collegian

It’s still hard to verbalize. I’ve had friends across state lines text and call me, wanting an explanation for how and why God chose now to come in this way. I admitted to all of them a phrase I usually despise: “I don’t know.”

And honestly, none of us do. But just because we don’t know all the details of God’s plan or His timeline doesn’t eliminate that He still moves. He still shows up. Funny enough, it always seems to be right when we need Him.

Alison Perfater, Asbury University Student Body President (WKYT)

“We are just sitting with Him. It’s just deeply gentle and deeply loving; it’s just a glimpse of what I think heaven will look like.”

Jason Vickers, Professor of Theology, Asbury Theological Seminary (Facebook)

In the time that I was there, I could not get over certain distinctive qualities about the atmosphere. The words that came to mind were: gentle, sweet, peaceful, serene, tender, still. Some people were singing. Others were talking. Many were praying. But there was something like a blessed stillness permeating the place. No one was swinging from the chandeliers. In fact, it was right the opposite. What made this so wild was just how un-wild the whole thing was … is.

Andrew Thompson, lead pastor, First Methodist Church, Tulsa, Oklahoma (Facebook)

All I can say about the experience I had over the next several minutes is that the manifest presence of the Lord is there – it is thick and substantial, and it is full of love. It is as if the Lord has set up his tabernacle right there over that room. The Holy Spirit covered me like a blanket, and then he began to flush out all the pain, and fatigue, and spiritual weariness I was feeling. I went down to the altar rail to pray, and an otherworldly peace came upon me such as I have only known one other time in my life. I felt two hands on my shoulders, and a voice began to pray over me: “Lord, walk with this man in his life. Let him know your presence. Fill him with your Holy Spirit.” When I later stood up, the two young college students who had been interceding for me were themselves praying at the altar. God is using his people to minister to one another in very humble, but bold ways.

Alexandra Presta, editor, Asbury Collegian

Peers, professors, local church leaders, and seminary students surround me – all of them praying, worshipping, and praising God together. Voices are ringing out. People are bowing at the altar, arms stretched wide. A pair of friends cling to each other in a hug, one with tears in her eyes. A diverse group of individuals crowd the piano and flawlessly switch from song to song. Some even sit like me, with laptops open. No one wants to leave.

No one even expected this to happen. Not on a random Wednesday for sure. Yet, we sit and sing about God’s love pouring out and His goodness.

Anna Lowe, Asbury Collegian

When I arrived at Hughes, my immediate inclination was to take photos and record what was happening through interviews, as my job typically requires. In my heart, I felt an outer nudge to be still. And so that’s what I did.

Nothing immediately happened to me or changed in my heart. …. I did not let the lack of immediacy deter me, even though I thought about leaving. All that mattered at that moment was our Creator. The transfer of my focus nudged me to ponder how infinitesimally small we are. The situations that enraptured my mind were mere specks on the horizon compared to eternity.

My heart shifted, and a resentment that had followed me for months was lifted by the grace of God alone. Walls of bitterness and agitation released themselves from my mind. I felt them cast out of my mind and heart to the point where I have almost completely forgotten the prior feeling. Knowing myself, I am confident this shift is not of my own volition. I was set and satisfied in my resentment, but God had different plans for me.

This moment of absolute peace shifted my reality.

Craig Keener, Professor of Biblical Studies, Asbury Theological Seminary (Facebook)

The university chapel (seating 1500) and seminary chapels (seating 1000) and a local church are filled and lines are waiting outside. But what strikes me most is that, even walking near the chapel or out on the street (itself full of cars), I CAN FEEL THE TANGIBLE PRESENCE OF GOD. Not something that can be manufactured. We’d prayed for this to happen someday, but it’s still way beyond my expectations!

Jake Traylor, associate producer, MSNBC News (NBC)

On TikTok and Instagram, videos hashtagged “Asbury Revival” are racking up millions of views. At the time this article was published, the hashtag #asburyrevival had 24.4 million views on TikTok. …

Tuesday night [February 14] capped the largest crowd yet: 3,000 worshipers piled into the college chapel and four overflowed facilities throughout the college town. At least two-thirds of the attendants are from out of state …

Students and staff from 22 schools have visited so far, alongside groups from Hawaii to Massachusetts, university faculty said. Travelers from Singapore and Canada are expected to arrive soon, they added. …

Nick Hall, an attendee who purchased a one-way plane ticket from Minneapolis when he saw a viral video on Instagram, emphasized that the gathering was notably low-key for something that people are calling a “revival.”

“This is acoustic guitars, pianos and very noncharismatic speakers. This is as un-sensationalized as it could be,” he said.

And according to Hall, leading the charge in the sanctuary and on social media is the Gen Z generation.

“They’re the ones that started it, they’re the ones that sustained it, and they’re the ones that have been on the platform the whole time,” he said.

Stephen Seamands, Professor Emeritus of Christian Doctrine, Asbury Theological Seminary (Facebook)

In revivals, said [First Great Awakening preacher and theologian] Jonathan Edwards [1703-1758], people get seized, gripped, overwhelmed by the divine excellency of Christ. As a result of being captured by his love, his “superlative amiableness,” as he puts it, they fall in love and stay in love with Jesus in such a way that their lives are never the same, the church is never the same, the world is never the same.

These first hand revival experiences, convictional experiences, divine encounters – grip us so profoundly, transform and shape us so deeply that they set us on a trajectory that continues for the rest of our lives.

Like Paul’s encounter on the Damascus road, they impart to us such a profound awareness, such a revelation of the risen, exalted Jesus, such an experience of his presence in us through the Holy Spirit, such an unswerving commitment to his mission, that standing in chains before King Agrippa decades later, he would declare, “No matter what happens, I simply can’t be disobedient to such a heavenly vision.”

Revivals produce Christians who are faithful, bold, and unapologetic. Christians who find their joy and satisfaction in God. Christians with a love and passion for holiness, who will gladly lay down their lives for Jesus, who are looking, not for a prosperity gospel, but in Amy Carmichael’s words, “a chance to die.”

Revivals cause the church to move forward in purity, power and unity; in boldness and confidence to be his witnesses. As a result God’s people are able to withstand cultural pressures to conform and compromise. They refuse to be seduced by the gods of their culture.

I think Jonathan Edwards had it right. We need revivals because we need more of Jesus. Through revival God raises up a generation, a people, a church which gets focused on Christ. As the characters in Narnia would say: “Aslan comes in sight.” So we discover things about him that we never knew before. He truly becomes the pearl of great price. Ultimately, revivals are about “the divine excellency of Christ.”

Elizabeth Glass Turner, writer and editor (Facebook)

Let it be what it is. Is it Holy Spirit, or hype? On watching and listening, here’s what I find: On February 8, a preacher shared what they named a mediocre sermon, but at the prayer of confession, something broke loose; and college students didn’t leave chapel service, but continued it. It kept continuing. Before social media lit up, there was just – simplicity. No one was trying to manufacture An Experience.

That’s really important to distinguish – the Holy Spirit met these students, at that moment, not to recreate the 1970s, but as a sweet movement for these lives, now. So whether they’d stayed an hour past usual chapel time, or three hours, or twelve hours, or twenty-four, if it had stopped then, that would’ve been okay; it wouldn’t have meant that the Holy Spirit wasn’t at work. It’s okay to let it be whatever it is, without putting pressure on college students to frame it a certain way.

Of course, in the 70s, there wasn’t social media; I think I first saw a comment online (from someone not present) less than 12 hours after it started, making swift comparisons. Let it be what it is, I thought. Whether it quiets to a hush and wraps up or lingers and continues, there’s grace in simply receiving. Like manna, yes? Don’t try to hoard it for the next day; simply receive the bread of heaven with thanks today. What’s funny is that smartphone-laden students weren’t trying to make anything go viral; weren’t trying to leverage as influencers. They were busy praying, confessing, worshipping. …

Exhausted, sad, burned, or desperate friends: skeptic or seeker, let’s let this be what it is. Negative experiences of emotionally charged, individualistic worship that doesn’t bear fruit are real; they also don’t mean this outpouring can be reduced to that. It’s okay to gently hope. And collective strain, exhaustion, burnout, and desperation should absolutely drive us to the feet of Jesus; that doesn’t mean our hopes should pin on one specific path or outcome this outpouring may or may not take or result in. If it quiets to a hum or holy silence, that doesn’t mean it wasn’t real, genuine, beautiful, transformative or holy – whether you’re doubtful or desperate. …

The predominant theme I’ve noticed from folks who popped over for a few minutes or longer – deep, deep, deep, quiet peace. Restorative peace. Deep, quiet joy. Not a circus, not a bunch of antics. God’s Spirit, like a weighted blanket. …

This started with a prayer of confession. If there’s any corner of your heart tempted toward being a consumer of an experience, know that uncomfortable remorse may come first. Some of the crowds around Jesus came face to face with that dynamic. The great thing is that reckoning and revival have a long history together, and you can share in prayers of confession wherever you are. (My favorites always pinch, always close loopholes: “what we’ve done and what we’ve left undone; we have not loved you with our whole hearts or our neighbors as ourselves” etc.)

Beth Felker Jones, Professor of Theology, Northern Seminary (Facebook)

• An event doesn’t have to be everything to be good. God works in partial, broken things.

• If we want to know something by its fruit, we have to give it some time to grow fruit.

• Judging something from afar, via Twitter, seems ill advised. Discerning the spirits is important. It’s best done in embodied communal relationship and not as a hot take …

• God made, loves, and works through emotions. Can emotions be manipulated or sinful? Yes. Does that mean emotion is out of bounds in Christian life? By no means!

• Our culture is so materialist. Are we prone to believe that a powerful, tangible work of the Spirit simply cannot be a real thing?

Peter J. Bellini, Professor of Church Renewal and Evangelization, United Theological Seminary (Facebook)

Revival often is dealing with the larger mystery and providence of God. We should all take a holy pause and breathe in before we claim to be able to judge the work of God. In one regard, we are all amateurs.

Tom McCall, Professor of Theology, Asbury Theological Seminary (Christianity Today)

As an analytic theologian, I am weary of hype and very wary of manipulation. I come from a background (in a particularly revivalist segment of the Methodist-holiness tradition) where I’ve seen efforts to manufacture “revivals” and “movements of the Spirit” that were sometimes not only hollow but also harmful. I do not want anything to do with that.

And truth be told, this is nothing like that. There is no pressure or hype. There is no manipulation. There is no high-pitched emotional fervor.

To the contrary, it has so far been mostly calm and serene. The mix of hope and joy and peace is indescribably strong and indeed almost palpable – a vivid and incredibly powerful sense of shalom. The ministry of the Holy Spirit is undeniably powerful but also so gentle.

Luther Oconor, Associate Professor of Global Wesleyan Theology, Asbury Theological Seminary (Facebook)

The Asbury Revival is still showing no signs of slowing down even after over 160 hours. People are just coming from nearby states and even as far as Florida. Last night, Hughes Auditorium was full, and services overflowed to the seminary chapel and at another auditorium on campus. By God’s sovereign grace, the partition between heaven and earth in Wilmore, Kentucky, seems to be thin or nonexistent.

As I reflect on this I am reminded of this observation by Mark Stibbe about revival: “Christian revival is a divinely initiated process in which a dying church is revitalised through the power of the Holy Spirit, leading to a new love affair with Jesus Christ, which in turn transforms the community, region, and even nation in which that church is situated” (“Seized by the Power of Great Affection,” in On Revival: A Critical Examination, 2003).

While the definition is a bit local church-centric, it still helps us understand that what we’re seeing at Asbury right now is the early stages of a revival. It is clear that a new love affair with Jesus Christ is taking place in Wilmore. Through the power of the Holy Spirit, people, mostly young people, are experiencing the love of Jesus for the first time or in such powerful ways that they are beginning to love him back. Jesus is glorified. For this is what happens when Holy Spirit shows up! He points us to Jesus (John 15:26). He removes the veil and we begin to gaze at him and are thereby transformed, and in this case, collectively (2 Corinthians 3:16-18). This is why the slogan at the altar at Hughes, “Holiness unto the Lord,” which also points to the rich Wesleyan-Holiness heritage to which Asbury is connected, sounds more like a prophetic unction to what is currently happening.

But transformation, as pointed out in the quote above, comes in stages. For love for Jesus overflows to love for neighbor. And so, it initially touches the local community, and so far the Asbury Revival is on track towards that. But as far as its implications to region, nation, and, if I may add, the world is concerned, that will take a while to determine. Only time will tell.

As several scholars have pointed out, there is always a link between genuine revival and social transformation (see the works of Timothy Smith, Don Dayton, Doug Strong, and others). But as the deep well of Asbury’s revival past has shown us, I won’t be surprised if years from now we will hear of people who will point to the revival of 2023 as a watershed moment for their lives. I somehow intuitively know this because I am a result of a powerful revival in the Philippines in 1997. There’s not a day I don’t look back to what God did to me then. Hence, I am confident that there will be a future generation of pastors, evangelists, healers, and missionaries who will emerge from this. The famous missionary from India, E. Stanley Jones, points to the Asbury Revival of 1905 which launched him into a long and fruitful missionary career. …

What matters most is we celebrate and thank God for what’s happening in this moment. One simply cannot complain that an infant doesn’t know how to drive yet! Let’s enjoy every moment with that baby and be excited about her or his potential. For when college students (yes, the same kids of the Gen Z TikTok generation!) are turning to Christ in droves, when people are reporting healings from emotional hurts and illnesses, or when people gain a new love for Jesus and neighbor through the power of the Holy Spirit, that is always a win in God’s Kingdom. May it be so on earth as it is in heaven.

I John 1:1-4

From the very first day, we were there, taking it all in – we heard it with our own ears, saw it with our own eyes, verified it with our own hands. The Word of Life appeared right before our eyes; we saw it happen! And now we’re telling you in most sober prose that what we witnessed was, incredibly, this: The infinite Life of God himself took shape before us. We saw it, we heard it, and now we’re telling you so you can experience it along with us, this experience of communion with the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ. Our motive for writing is simply this: We want you to enjoy this, too. Your joy will double our joy!

– The Message

Photo: Hughes Auditorium at Asbury University, February 10, 2023. Photo by Sarah Thomas Baldwin. Used by permission.