by Steve | Mar 13, 2024 | March/April 2024

Room for Fairness in Charlotte

By Rob Renfroe

I believe most United Methodists are good, decent people. That may sound strange coming from one who has passionately argued that orthodox Christians would do well to leave The United Methodist Church. But my problem with the UM Church has not been with its people. My disagreements have been about principles and policies and theology. And good people can differ on those things.

My experience has been that the vast majority of United Methodists strive to be kind, want to embrace everyone with the love of God, believe in being fair, and are doing their best to make the world a better place. I think Garrison Keillor of Lake Woebegone fame got it right when, after having some fun with our quirks, he wrote, Methodists are “the sort of people you can call up when you’re in deep distress. If you’re dying, they will comfort you. If you are lonely, they’ll talk to you. And if you are hungry, they’ll give you tuna salad.”

Keillor could have added, Methodists are usually the ones running the local food pantry, leading the town’s Rotary Club, and hosting the annual Martin Luther King Day celebration for their community. United Methodists, whether traditional, centrist, or progressive, tend to be good people doing good things.

That’s what gives me some hope for the upcoming General Conference that convenes in April. The United Methodist Church needs to do a good thing, the right thing, the just thing and provide a way for churches outside the United States to disaffiliate in a way similar to what was afforded to congregations here in the U.S.

I know United Methodists in the United States want to move beyond disaffiliation. They want to be and need to be looking forward. They possess an understandable desire to be done with the hurt and chaos that disaffiliation has created. But you can’t be done with something that hasn’t begun. And the opportunity for churches outside the U.S. to leave the denomination hasn’t begun.

Our bishops ruled, rightly or wrongly, that the legislation passed in 2019 that allowed churches in the United States to leave did not apply to churches in other countries. So, for our brothers and sisters in Africa, the Philippines, Europe, and Russia, the opportunity for disaffiliation has not yet begun.

If the UM Church decides that it’s done with disaffiliation, it will be the church that tells the world that it is proper and fair to possess one set of rules for churches in the U.S. and a different set of rules for churches in other countries, most of which are in Africa.

If the UM Church decides to move forward without providing a fair exit path for international churches, it will disqualify itself from talking to the culture about doing justice. Give churches in this country that are primarily white and wealthy privileges that it does not afford to congregations outside the U.S., most of which are poor and persons of color, and The United Methodist Church will lose the moral high ground to speak to others about colonialism, racism, or justice.

When I met with forty African leaders in Nairobi last September, they were skeptical whether General Conference would give them the same rights and privileges we in the U.S. were given. They believe they are seen as “a problem” by many centrists and progressives in the U.S. They are accustomed to being treated as “less than” by the UM Church. They know the majority of United Methodists live in Africa, but receive only 32 percent (278 out of 862) of the delegates to General Conference.

They are aware that the Standing Committee on Central Conferences (the committee that oversees the work of Conferences outside the U.S.) has more than a third of its members from the U.S. – giving the U.S. an outsized say in how the Central Conferences operate. They still remember Bishop Minerva Carcano’s demeaning statement several years ago that they should “grow up and start thinking for themselves.”

They have not forgotten the Rev. Mark Holland of “Mainstream UMC” stating after General Conference 2019 that a continued partnership with the Africans might not be possible because they don’t appreciate or affirm our American culture. “A two thirds (2/3) majority of the U.S. church voted for cultural contextualization through the One Church Plan,” Holland wrote after the General Conference. “It was telling that eighty percent (80%) of the delegates from outside the U.S. declared, through their support of the Traditional Plan, that they are unwilling to allow the U.S. jurisdictions the same cultural contextualization they enjoy. This lack of reciprocation from delegates outside the U.S. may well lead to the end of our connection as we know it.”

Holland went on to state: “While there is no question that the U.S. church must continue to be in mission and ministry around the world, it is impossible to share a governance structure with a global church which is both fundamentally disconnected from and disapproving of the culture of the United States.”

The African leaders in Nairobi, from more than two dozen countries, are also aware that the real intent beneath the proposal for “regionalization” is to marginalize Africa’s ability to speak into the practices of the church in the U.S. So, it wasn’t surprising at the meeting in Nairobi that when one respected pastor referred to regionalization as “the apartheid plan,” there was no pushback, only heads nodding in agreement.

I understand why our African brothers and sisters are dubious that they will be treated fairly and justly when the General Conference meets in Charlotte this spring. I understand it will be easy for the delegates there to say, “we’re done with disaffiliation, and we need to move on.”

It will be tempting to forgo the difficult, unpleasant work of creating an exit path for those outside the U.S. who might want to leave. But if the delegates in Charlotte refuse to do the right thing for our international brothers and sisters, that would mean United Methodists, at least those representing us, are not really decent people who are committed to doing justice, no matter how many lonely souls they talk to, or how many international mission projects they support, or how many hungry people they bring tuna salad.

I refuse to believe that’s who United Methodists are – a people accepting of discrimination and who refuse to give others the same rights we in this country were given. I feel certain we are better than that. I pray – and in my heart of hearts I do believe – that traditional, centrist, and progressive United Methodists will do the right thing and provide justice for our brothers and sisters in Africa and around the world. In three months we’ll know if I’m right or wrong.

by Steve | Mar 8, 2024 | In the News, Perspective / News

African Regionalization Support Not Unanimous

By Forbes Matonga

(This week, UM News ran two commentaries from United Methodists from Africa dealing with pivotal issues that will be before the upcoming General Conference in Charlotte. We encourage United Methodists to read both pieces. For this week’s Perspective, we are featuring the commentary by the Rev. Forbes Matonga, a pastor and General Conference delegate from the Zimbabwe West Annual Conference. – Editor)

The United Methodist Church continues to be an exciting organism. It never stops, especially during General Conference season. We are exactly in that season again.

One of the complex dynamics of The United Methodist Church is the existence of pressure groups, commonly known as caucuses. Historically, caucuses were largely an American phenomenon, unknown to African United Methodists.

In the U.S., these groups took the flavor of national politics. Thus, the division was clearly along the lines of conservatives vs. liberals or traditionalists vs. progressives. It used to be that when Africans got to General Conference, they were amazed to see how these groups would solicit their votes, at times using demeaning methods I shall not describe here.

Over time, Africans realized that they do not exist at General Conference to push American interests. They have their own. African interests have included funding for Africa University, funding for theological education in Africa and fair representation on boards and commissions of the general church, to name a few.

The need for Africans to advocate for their own interests led to the formation of the first African caucus, named the Africa Initiative. This group was able to galvanize African delegates into a force that could not be ignored.

American conservative caucuses quickly formed alliances with the Africa Initiative that included providing financial support to gather and strategize. Progressive American caucuses, meanwhile, supported the startup of other African groups that differed from the Africa Initiative. They provided funding and helped these groups strategize.

Africa was targeted because its delegate numbers were growing, while American numbers were decreasing.

This sets the context to understand what was happening in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, recently, where Africans attending the United Methodist Africa Forum gathering are said to have unanimously endorsed regionalization and rejected disaffiliation by the same margin. Those who made this big decision included some African delegates and alternate delegates to the upcoming General Conference in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The first thing that makes this gathering interesting is the presence of big names in the United Methodist hierarchy, such as the chair of the Connectional Table, who happens to be the resident bishop of the hosting episcopal area including Tanzania. This is a sign of an express approval of this group by the powers that be in the denomination, both in Africa and globally. By contrast, in 2022, the African bishops denounced the Africa Initiative and the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

The question must be asked: How legitimate was the Dar es Salaam gathering?

I am the head of the Zimbabwe West Annual Conference delegation to General Conference. We were not invited to Dar es Salaam. I know in fact that no delegates from either Zimbabwe West or Zimbabwe East or the Malawi Mission Conference attended this gathering or the first Africa Forum gathering in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2023. I may not be qualified to speak for all African delegations to the General Conference, but this is the case for the Zimbabwe Episcopal Area.

The United Methodist Africa Forum may speak for itself and pronounce its position, but it does not speak for me or the Zimbabwean delegates. The Africa Forum is not a forum for all African delegates.

The Africa Initiative, which has a substantial number of General Conference delegates as its members, clearly opposes the regionalization agenda. The initiative’s position is regularly articulated by its general coordinator, the Rev. Jerry Kulah of Liberia, a General Conference delegate himself.

A few African delegates have since moved away from The United Methodist Church in response to a wave of disaffiliations that hit the U.S. United Methodist Church, leading to the birth of the Global Methodist Church. However, most African delegates to General Conference chose to remain in The United Methodist Church, contending for the retention of the disciplinary language that prohibits same-sex weddings and the ordination of “self-avowed practicing” homosexuals anywhere in The United Methodist Church. This African group is very much alive and very capable of frustrating the liberal agenda to change the position of the church on human sexuality.

Let me stress this point: Regionalization as proposed does not go far enough to assure Africans that their position against the affirmation of same-gender relationships will not be compromised under the so-called big tent theological umbrella. Indeed, as long as the Council of Bishops itself is not regionalized, then this whole talk of regionalization is a smokescreen.

Currently, bishops of The United Methodist Church are bishops of the whole church. A gay bishop elected in America is a bishop for Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This is what Africa is rejecting. I hope our progressive and centrist brothers and sisters will understand that this time around.

The regionalization legislation requires a constitutional amendment, which needs approval by two-thirds of the delegates, plus two-thirds of all annual conference members across the globe. That’s not going to happen.

Many African delegates, who are the principal reporters to annual conferences on the outcomes of the General Conference, will advocate against regionalization, and it will fail at the annual conference level — even if progressives somehow get a favorable vote at General Conference.

It is instructive to note the pushback Pope Francis is getting from African Catholics for trying to promote liberal theology on human sexuality. They are rejecting his reasoning that one can bless gay people without marrying them while they are living as married couples. The United Methodist Church will, if it veers from its current policies on human sexuality, face similar pushback from Africans.

It is written, “A man will leave his father and his mother and be united to his wife, and they will become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24, NIV). “…. and he (Jesus) said, ‘For this reason, a man will leave his father and his mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh’” (Matthew 19:5, NIV). “For this reason, a man will leave his father and his mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh” (Ephesians 5:31, NIV).

We African United Methodists shall listen to no other voice, be it from angels, those who call themselves apostles, theologians, biblical scholars, or philosophers of this world. We trust the Word of God as given in Scripture! SOLA SCRIPTURA!

Forbes Matonga is an ordained pastor and a General Conference delegate in the Zimbabwe West Annual Conference. The Rev. Forbes Matonga, a clergy delegate from the West Zimbabwe annual conference, speaks to the 2016 United Methodist General Conference in Portland, Oregon. Photo by Paul Jeffrey, UMNS.

(As a counterpoint to Rev. Matonga’s piece, UM News also ran a commentary from the Rev. Gabriel Banga Mususwa. You can read it here. – Editor)

by Steve | Mar 1, 2024 | In the News, Perspective / News

Why We Will Be in Charlotte

By Thomas Lambrecht

Two recent stories from United Methodist News deserve a response. The first was a news article about the announced intention of Good News and the Wesleyan Covenant Association (WCA) to participate in the upcoming General Conference in Charlotte, NC, in April.

The second article was a commentary by the Rev. Lovett H. Weems Jr. further criticizing Good News and the Wesleyan Covenant Association (WCA) for our involvement. The argument voiced in both articles is that only those who have a long-term commitment to the UM Church should participate in deciding the future of that church.

In the words of the Rev. Drew Dyson, a delegate from Greater New Jersey, “Our polity should be determined by those whose intention is to remain faithfully within the UMC. In my estimation, Good News and the WCA are simply attempting to undermine and harm the work of the UMC under the guise of ‘fairness’ for their allies.” There were a handful of other critical responses in the news article. Fair enough. (It should be noted that both Good News President Rob Renfroe and I remain ordained clergy in good standing in the UM Church.)

Since 1972, Good News has participated in every General Conference by expressing our views on topics up for consideration at the conference. We have helped to organize like-minded delegates to support traditionalist positions on issues. Other caucus groups, such as Methodist Federation for Social Action, Reconciling Ministries Network, and other more liberal groups have engaged in similar activity at these same General Conferences. In the past, the Love Your Neighbor Coalition has even recruited non-United Methodists to come and participate in protests that have disrupted the functioning of the General Conference.

Our participation in the 2024 General Conference, however, will be different. Rather than lobbying the delegates on a host of issues of concern, Good News and the WCA are in Charlotte to focus on only two issues. First is the need to provide equitable, feasible disaffiliation routes for annual conferences and local churches outside the U.S. who have been denied the possibility that we in the U.S. had to discern our future. Second is to support our African friends in their opposition to the proposed regionalization of the church.

We will not be in Charlotte to “undermine and harm the work of the UMC” in any way (unless one considers enacting fairness and justice harming the work of the church). We will not be lobbying on the budget or attempting to block changes to the denomination’s definition of marriage and ordination standards. We will not be critiquing the proposed new Social Principles or weighing in on the number of bishops the church should have.

The future of the UM Church is for those who will be living with that future to determine. The question is, however, who will be part of the future UM Church. Will the church be a “coalition of the willing” or a “fellowship of the coerced?”

Is Disaffiliation Over?

The heart of the institutional UM narrative is that, in Weems’ words, “The period of disaffiliation is over. It is time for all groups to move on from dividing to unifying and disciple-making.”

Who gets to say that the period of disaffiliation is over? Institutional leaders in the U.S.? People who have already had the chance to discern their future in the UM Church?

How can disaffiliation be over when more than half the UM Church has not had an opportunity to consider disaffiliation, much less act on it? If the shoe were on the other foot, would the charge of colonialism be leveled? U.S. leaders should not be the lone arbiters for determining that the privileges and opportunities available in the U.S. will not be allowed in the central conferences outside the U.S.

There are other questions of fairness:

- How can disaffiliation be over when several annual conferences convinced some of their churches to wait to see what the 2024 General Conference does before considering disaffiliating?

- How can disaffiliation be over when a dozen U.S. conferences imposed such draconian costs on the process that it has been nearly impossible for churches in those conferences to afford to disaffiliate?

- How can disaffiliation be over when one annual conference said in late 2023 that churches had no grounds under the Discipline or Par. 2553 to disaffiliate and denied all further requests?

- How can disaffiliation be over when there are at least four lawsuits underway in annual conferences that have made it nearly impossible for churches to disaffiliate?

Weems writes, “The upcoming General Conference is for those who remain after the chaos of recent years. … They have chosen to remain not because they all agree, but because they are willing to live together despite differences.” Unfortunately for Weems, nearly half the delegates there have NOT chosen to remain. They have not been given the choice. In denying them the choice, the UM Church has handicapped itself and compromised its ability to move forward in a new direction.

Disunity Incompatible?

Weems states that “disunity is incompatible with Christian teaching.” It is easy to make that glib statement and point to Jesus’ prayer in John 17:21, “that all of them may be one.” At the same time, one must acknowledge that Christian unity is not necessarily expressed by all Christians being in the same denomination. Otherwise, we would all have to become Roman Catholic.

Unity is built on a common faith in Jesus Christ and a willingness to work together for the cause of the Gospel, regardless of denominational affiliation. Such unity and cooperation is less likely to develop in the aftermath of the imposition of punitive costs or the denial of equal rights and fairness.

At times, it may be pragmatically better to separate and work independently for the Gospel when people are unable to agree sufficiently to work together. Paul and Barnabas found that to be the case, as recorded in Acts 15:36-41. In the wake of the unity engendered by the Council of Jerusalem, they had a “sharp disagreement” and parted ways for their second missionary journeys.

Weems recounts that John Wesley and George Whitefield disagreed “vehemently” over some aspects of doctrine. Weems believes, however, that “Wesley concluded that it was better for the cause of Christ for them to work together, despite their differences, than to separate.” However, Wesley and Whitefield did separate in 1741. While they still considered each other brothers in Christ, and Wesley preached Whitefield’s funeral sermon in 1770, they did not work together in any organized way after 1741. Those who held a Calvinist doctrine were not allowed to preach in Methodist preaching houses.

This was one of the first of many separations that occurred within Methodism, on average one every ten years during the first century of Methodism’s existence. Separation, however, does not have to mean disunity. It will take a time of healing of wounds on both sides of the latest separation, but the possibility remains of some form of cooperative unity in the future between those who remain United Methodist and those who have separated. All on both sides should continue to strive now to maintain an attitude of graciousness toward those with whom we disagree in order to minimize the healing that is needed and hasten the opportunity for constructive cooperation.

I agree with Weems’ invitation to that graciousness: “In a country seemingly unreconcilably divided today, is not God calling us to put aside the accumulated acrimony and bitterness from years of words and deeds for which we all could have done better and wish for each other God’s blessings for the future?” Absolutely! Restoring fairness for all could go a long way toward putting “the accumulated acrimony and bitterness” behind us and enabling a positive future working relationship.

Agree on All Topics?

Weems describes the people who choose to remain United Methodist as “compatibilists.” He defines them as those “who do not expect all other members to agree with them on all topics.”

Anyone who has read a Twitter feed or Facebook group of Global Methodists and other disaffiliated persons knows we do not agree with each other on “all topics.” Traditionalists have remained a constructive part of United Methodism and its concomitant pluralism for over 50 years. It is only when the church failed to uphold its own teachings and disciplines that many traditionalists could not in good conscience remain in connection.

From all indications, the upcoming General Conference will most likely change the church’s definition of marriage to allow for same-sex marriage. Furthermore, it is expected to change the ordination standards to allow for the ordination of partnered lesbians and gays. For many traditionalists, this would be a contravention of the plain teachings of Scripture.

Not all traditionalists believe that disagreement over these issues is a church-dividing issue. But we believe those who do should have a fair opportunity to disaffiliate from a church that is changing its teachings and practices in these vital areas. Congregations and annual conferences that in conscience cannot support this change should not be required to forfeit their buildings and property and abandon their mission in order to disaffiliate.

We will be in Charlotte to give voice to those traditionalists who have not had a fair opportunity to disaffiliate, some in the U.S., but mostly in the central conferences outside the U.S. We pray the General Conference delegates will see the justice of our cause and respond in a way that opens the door for congregational self-determination and ends the unfair discrimination against Africans, Filipinos, and Europeans who cannot support the evident new direction of the UM Church.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News. Charlotte, North Carolina. Photo: Andres Nino, Pexels

by Steve | Feb 23, 2024 | In the News, Perspective / News

Unpacking Disaffiliation

By Thomas Lambrecht

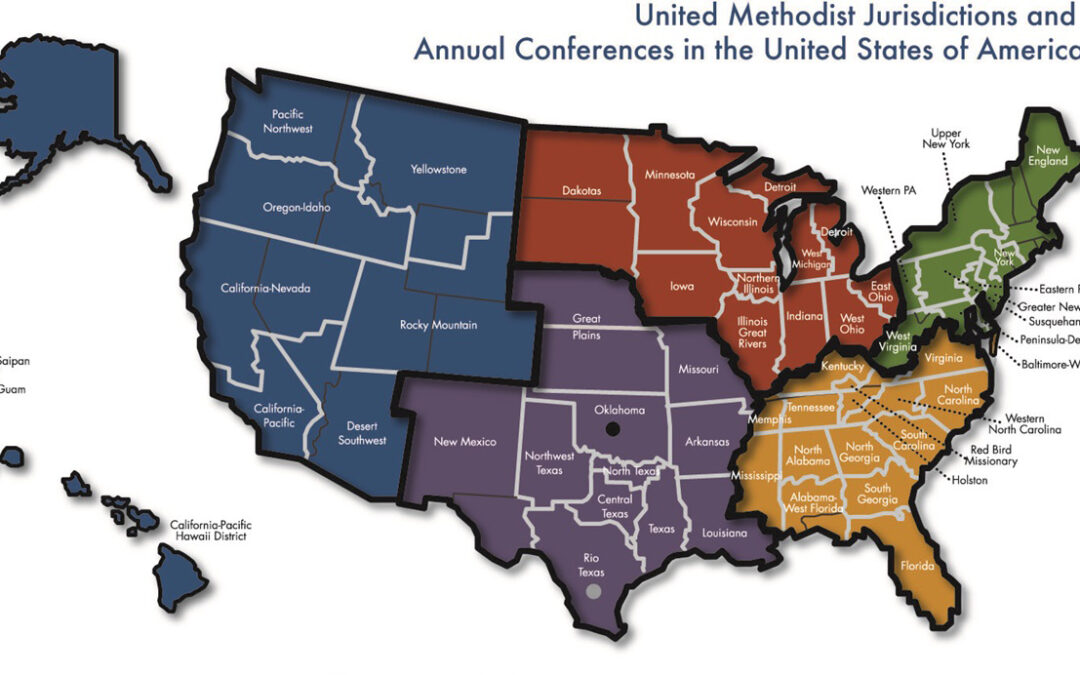

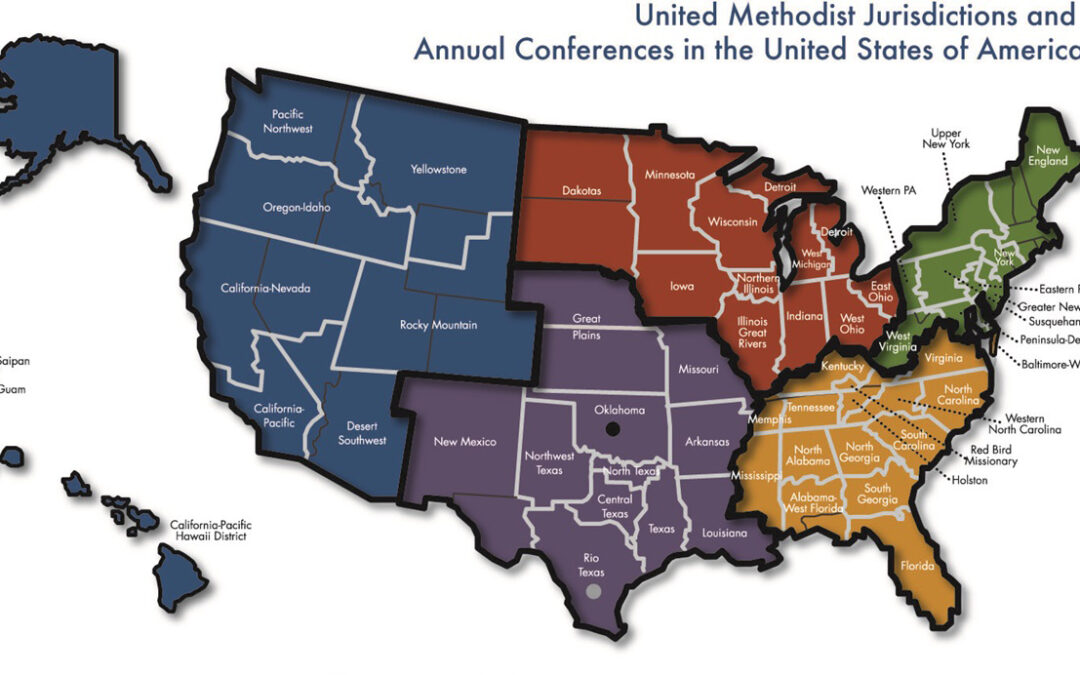

By my count, as of December 31, 2023, 7,651 churches have disaffiliated from The United Methodist Church in the U.S. since 2019. This represents 25.8 percent of the number of churches that were listed by the denomination in 2019.

Dr. Lovett Weems, of the Lewis Center at Wesley Theological Seminary, has published a helpful report analyzing the results of disaffiliation, noting the common characteristics of disaffiliating churches and pointing out salient differences. This Perspective will piggy-back on Weems’ analysis with some points of my own.

What conferences were most affected?

The Southeast Jurisdiction led the way with 37 percent of its churches disaffiliating. The conferences most affected were:

- South Georgia – 61 percent disaffiliated

- North Alabama – 52 percent

- Kentucky – 50 percent

- North Georgia – 48 percent

- Alabama-West Florida – 46 percent

- Tennessee-Western Kentucky – 42 percent

- North Carolina – 41 percent

Besides the Red Bird Missionary Conference, which lost no churches to disaffiliation, the only conferences that showed fewer than the 26 percent denominational average for disaffiliation were South Carolina, which blocked disaffiliation for many churches and for a long period, and Virginia, which imposed additional fees for disaffiliation. South Carolina continues to allow churches to disaffiliate via Par. 2549 by moving to “close” the church and then sell it to the congregation. An additional 100 churches or more are reportedly currently engaged in this process.

The South Central Jurisdiction had 32 percent of its churches disaffiliate. The jurisdictional numbers were heavily influenced by high levels of disaffiliation in some of the Texas conferences. The conferences most affected were:

- Northwest Texas – 82 percent disaffiliated

- Texas – 51 percent

- Central Texas – 45 percent

- Louisiana – 38 percent

The rest of the South Central annual conferences experienced percentages much closer to the denominational average of 26 percent. The three Texas conferences above facilitated disaffiliation by absorbing the cost of the pension liability and, in Northwest Texas, absorbing even the cost of the two years’ apportionments. So churches in those conferences were able to disaffiliate at a minimal cost.

The North Central Jurisdiction had 22 percent of its churches disaffiliate. The conferences most affected were:

- East Ohio – 38 percent disaffiliated

- West Ohio – 34 percent

- Indiana – 31 percent

Northern Illinois made it very difficult for churches to disaffiliate and had only 2 percent do so. Illinois Great Rivers imposed additional costs for disaffiliation and had only 10 percent of their congregations do so in a conference that tends to be more conservative. Minnesota had 7 percent and Wisconsin 10 percent disaffiliate. The rest of the conferences were near the average.

The Northeast Jurisdiction had only 12 percent of its churches disaffiliate. Seven of the ten Northeastern annual conferences imposed additional costs or otherwise discouraged disaffiliation. Six annual conferences therefore experienced less than 5 percent of their churches disaffiliating. Two of those conferences are currently in lawsuits filed by churches unable to disaffiliate who wanted to do so. The only outlier was Western Pennsylvania, which had 38 percent of its churches disaffiliate.

The Western Jurisdiction had only 6 percent of its churches disaffiliate. Four of the seven annual conferences imposed additional costs or otherwise discouraged disaffiliation. One of the conferences is in a lawsuit with churches unable to afford the imposed 50 percent payment of property value in order to disaffiliate.

Who Is in the GMC?

Weems’ report mentions that fewer than half of the churches that disaffiliated have joined the Global Methodist Church (GMC). That was based on the information he had at the time, but churches are joining the GMC each week, so that number is increasing. At the time of this writing, there were approximately 4,100 churches in the GMC, of which about 3,850 are in the U.S. Therefore, at this point about half of the U.S. churches that disaffiliated have joined the GMC. Many are still in the process of discernment, while paying off the debt incurred for departure fees. Others are waiting to see how the denomination develops in light of its inaugural General Conference scheduled for September of this year.

One can see from this that joining a denomination was not a high priority for many disaffiliated churches. It is sad that their experience with the UM Church was such as to make them reluctant to join another denomination after disaffiliation. It may be that some churches would just rather be independent, but it may also be that a number of churches are suffering from post-denominational trauma and need healing before considering aligning with another denomination. Eventually, many of these wounded churches will see the value of being part of something bigger than themselves and seek out an alignment that fits their ministry passion.

One should also acknowledge that several dozen disaffiliated churches have joined other denominations, such as the Free Methodist or Wesleyan Churches. Some have formed their own independent networks. The percentage of non-aligned churches may be less than it appears, and it will shrink over time.

Reasons for the difference in disaffiliation

As pointed out above, some annual conferences made it much easier to disaffiliate, while other annual conferences made it more difficult. Conferences that followed a straight Par. 2553 process without additional costs experienced an average 28 percent disaffiliation rate. Conferences that imposed additional costs or made the process more difficult experienced an average 13 percent disaffiliation rate.

Conferences in the North and West that had a low disaffiliation percentage also have a history of more liberal/progressive policies. This was exhibited in resolutions on social issues, as well as a bias against admitting theologically conservative clergy and such clergy receiving less prestigious appointments. More traditionalist clergy and members have left the UM Church in those conferences down through the years prior to 2019, so there were not as many traditionalists left to disaffiliate.

Conferences in the South have had a more traditionalist theological milieu and retained many more of their traditionalist clergy and members prior to disaffiliation. There were thus more traditionalists to disaffiliate. The same was true in Western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, which were the heart of the Evangelical United Brethren Church. Those areas also retained a more traditionalist theological milieu and thus experienced a higher level of disaffiliations.

Weems wonders whether congregations in the South and Midwest did not fully embrace the unifications that took place in 1939 and 1968. While that may be a factor, it seems like the passage of time would mitigate that effect. It appears just as likely that the theological climate of the prior denominations carried over into the United Methodist denomination following merger, which then influenced the different directions these churches took.

Why more ethnic congregations did not disaffiliate

According to Weems’ research, ten percent of all UM congregations were majority people of color prior to disaffiliation, yet only three percent of disaffiliating churches were majority people of color.

The issue of race within United Methodism has always been a complex and sensitive issue to calculate, since the denomination is overwhelmingly populated by white congregations. In addition to United Methodism, our sister denominations – African Methodist Episcopal Zion, Christian Methodist Episcopal, and African Methodist Episcopal – have primarily African American membership.

Speaking in generalities, African American churches (70 percent of all ethnic UM churches) tend to be more conservative theologically, but more liberal politically. They face the dilemma of being a unique element in either a denomination that may be perceived to be more liberal both politically and theologically or a denomination that may be perceived to be more conservative both politically and theologically.

There is an understandable history of mistrust of white churches in the South – and perhaps other parts of the country – that participated in racial segregation in the past. There is also a well-established and laudable support system in the UM Church for black clergy, which would have to be built from scratch in a new denomination. These are only some of the unique factors that would accompany a discussion of disaffiliation.

In addition to cultural factors (and perhaps language considerations), there are some Hispanic congregations that are dependent upon support from the annual conference and/or meet in other UM congregations’ facilities. That makes disaffiliation more challenging. Furthermore, many Hispanic pastors are licensed local pastors and thus more vulnerable to being let go from their positions by bishops and committees on ordained ministry that are hostile to disaffiliation. Once again, their process of disaffiliation could face unique challenges.

Similarities in size

When disaffiliations were first ramping up in 2022, the word from some institutionalists was that most of the disaffiliating churches were small churches, and that the large churches were not disaffiliating. Weems’ research shows that not to be true.

According to Weems, similar proportions of churches disaffiliated at all size levels of worship attendance. In the UM Church, six percent of all churches averaged over 250 in worship attendance. Five percent of disaffiliating churches averaged over 250. In the UM Church, 13 percent averaged between 100 and 250 in worship attendance, while 12 percent of disaffiliating churches did so. In the UM Church, 82 percent of all churches averaged less than 100 in worship, while 83 percent of disaffiliating churches did.

Disaffiliating churches almost perfectly matched the size profile of the denomination as a whole.

As Weems writes, “Researchers have much with which to work in answering the many questions raised by the experience of the United Methodist Church from 2019 through 2023. If past divisions are predictive, there will be a host of partisan narratives. What will be most needed are objective scholars who can go beyond statistical data to representative surveys and qualitative research to answer some [additional] questions.”

While the ideas and explanations proposed above may seem partisan to some, they resonate with the statistics and with personal experience. Further research may bear them out or find different answers.

There is no question that a cataclysmic change has affected American Methodism and may yet heavily impact Methodism in other parts of the world. Aside from the statistical and sociological explanations for what has taken place, it would be wise not to ignore the spiritual aspects, as well. In many disaffiliating congregations, there was a clear sense of God’s leading and a desire to be faithful to non-negotiable theological perspectives. Many church members would have prioritized the spiritual factors leading to separation over the more pragmatic ones, and the spiritual factors will not necessarily show up in a statistical analysis. It is these spiritual aspects that will give unity and purpose to the Global Methodist Church, the UM Church, and to other entities arising out of this traumatic separation event.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News. Photo: Shutterstock.

by Steve | Feb 16, 2024 | Front Page News

The UM Church Adjusts to Fewer Bishops

By Thomas Lambrecht

In the aftermath of losing one-fourth of its congregations and members in the U.S., The United Methodist Church anticipates a number of adjustments to its ministry and structure. For example, UM News Service has reported that since 2016, general agencies have cut about 40 percent of their staff. This is in line with the proposed budget coming to the April General Conference in Charlotte, North Carolina, that calls for a 40 percent reduction in the quadrennial budget, making it the smallest budget proposed since 1984.

Adjustments are driven substantially by an anticipated drop in financial resources, and also by a drop in the number of churches and members. This second factor is an important driver in the number of U.S. bishops, which will be reduced by jurisdictional conference action this year.

Number of Bishops Set by Formula

The number of bishops to which each jurisdiction is entitled is based on a formula found in the Book of Discipline, Par. 404.2. Each jurisdiction is entitled to a base number of five bishops. The jurisdiction is then entitled to an additional bishop for every 300,000 members (or major fraction thereof) over the base number of 300,000. So, at 450,000 members, a jurisdiction would be entitled to six bishops, rather than five. At 750,000 members, the number would move to seven bishops, and so on.

Based on the formula and 2016 membership numbers, this is the number of bishops each jurisdiction had before disaffiliation began:

|

Members |

Eligible Bishops |

2016 Actual Bishops |

| North Central |

1,270,000 |

8 |

9 |

| Northeastern |

1,257,500 |

8 |

9 |

| South Central |

1,707,500 |

10 |

10 |

| Southeastern |

2,818,000 |

13 |

13 |

| Western |

340,500 |

5 |

5 |

| Total |

|

44 |

46 |

As the above chart demonstrates, both the North Central and Northeastern Jurisdictions were set to possibly lose a bishop in 2020, due to a decline in membership in those jurisdictions below the number set by the formula.

However, the number of bishops is not automatically set by the formula. Instead, the Interjurisdictional Committee on the Episcopacy (ICE) is tasked with recommending the number of bishops to be approved by the General Conference “on the basis of missional needs” (Par. 404.2b). The ICE can recommend retaining a higher number of bishops than the formula would allow. It recommended in 2019 that the number of bishops be retained as is for the 2020 General Conference, so that the denomination could see the results of the 2019 General Conference before deciding on any reductions.

Number of Bishops Reduced in 2023

In the aftermath of three postponements of the 2020 General Conference, the jurisdictions held special jurisdictional conferences in 2023 to allow bishops to retire who were mandated to do so by the mandatory age limits in the Discipline. Some of the jurisdictions voluntarily decided to elect fewer new bishops than they were otherwise entitled to elect. That way, if disaffiliation meant further reductions were necessary, some active bishops would not have to be forced out of office. It would give time to see how many churches disaffiliated and the impact on various annual conferences.

This is the result of that first “downsizing”:

|

2016 Bishops |

2023 Bishops |

| North Central |

9 |

9 |

| Northeastern |

9 |

6 |

| South Central |

10 |

8 |

| Southeastern |

13 |

11 |

| Western |

5 |

5 |

| Total |

46 |

39 |

This 15 percent reduction in the number of bishops was actually only an 11 percent reduction from the number that jurisdictions were entitled to in 2020. But it showed church leaders grappling with the potential of drastic changes coming in the wake of disaffiliation. The North Central Jurisdiction anticipated retirements in 2024 that would allow them to reduce their number of bishops as needed.

Number of Bishops Post-2024

Jurisdictions are still making plans regarding the election of bishops this summer in the wake of the 2024 General Conference. There are also several proposals to the General Conference to eliminate the above formula for setting the number of bishops. One of those proposals would have the general church pay for the initial five bishops, and then have each jurisdiction pay for any bishops it elects over that base five. None of the proposals would reduce or eliminate the requirement for a base of five bishops. Thus, they fail to address the greatest inequity, which is the Western Jurisdiction maintaining a full five bishops while other jurisdictions would have two to three times the number of members per bishop.

Based on 2019 membership numbers with an estimated adjustment of how many members were lost through disaffiliation, this is how many bishops would be allocated by formula in 2024, along with how many bishops each jurisdiction plans to allocate:

|

Post-Disaffiliation Members |

Eligible Bishops |

Current Bishops |

Projected 2024 Bishops |

| North Central |

745,000 |

7 |

9 |

7 |

| Northeastern |

864,000 |

7 |

6 |

7? |

| South Central |

950,500 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

| Southeastern |

1,500,000 |

9 |

11 |

10 |

| Western |

277,500 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Total |

|

35 |

39 |

36 |

If these projections hold, the number of U.S. bishops will have been reduced by 22 percent, from 46 to 36. That is in line with the General Council on Finance and Administration’s budget for a 23 percent reduction in the Episcopacy Fund for the 2025-28 quadrennium. At this time, it is unknown whether there will be money available for additional bishops in Africa, which were promised in 2016.

Under these projections, neither the North Central, the South Central, nor the Southeast would elect any new bishops in 2024. Depending on whether or not any currently active bishops retire, it is possible the Western Jurisdiction would not elect any new bishops, either. Some jurisdictions have yet to decide what their episcopal numbers will be, and that could also be influenced by actions taken at the General Conference.

Most of the reductions are the result of annual conferences moving to share a bishop.

- In the North Central Jurisdiction, Wisconsin and Northern Illinois will share a bishop, as will East Ohio and West Ohio.

- In the Southeastern Jurisdiction, North Alabama, Alabama-West Florida, and South Georgia will all share one bishop.

- In the South Central Jurisdiction, Northwest Texas, North Texas, and Central Texas will share a bishop, Oklahoma and Arkansas will share one bishop, and New Mexico and Rio Texas will share one bishop.

- In the Northeast Jurisdiction, Baltimore-Washington and Peninsula-Delaware are sharing a bishop, as are Eastern Pennsylvania and Greater New Jersey. New England and Susquehanna are both being covered by multiple bishops. It is very possible one more bishop will be elected in this jurisdiction and/or that annual conference borders will be realigned to provide more equitable episcopal areas.

All of this ferment illustrates the point that Good News has been making for several years. The UM Church following disaffiliation will be a different church than it was, both structurally and in its beliefs and teachings. Those who thought that by remaining United Methodist, everything would stay the same, are finding out that change was inevitable for all of us. The key will be to grasp this opportunity to make the churches of whatever denomination the most effective in their mission and ministry for the sake of Jesus Christ. It will be a challenging task for all, demanding patience, prayer, and sacrificial commitment to the greater mission.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Jurisdictional map created by United Methodist Communications.