by Steve | May 28, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May/June MJ 2021

By Steve Beard –

While sifting through obscure Spanish colonial records, it was discovered a few years ago that the very first St. Patrick’s Day parade was not conducted in Boston, Chicago, nor New York City.

Instead, the Irish feast day was celebrated in modern day St. Augustine, Florida, in 1601.

“They processed through the streets of St. Augustine, and the cannon fired from the fort,” said Prof. J. Michael Francis of the University of South Florida at St. Petersburg, who discovered the document. The ancient records named “San Patricio” as “the protector” of the area’s maize fields. “So here you have this Irish saint who becomes the patron protector of a New World crop, corn, in a Spanish garrison settlement,” he said.

This strange twist in the story and celebration of St. Patrick, a fifth century holy man, is really not that surprising. His memory is invoked all around the globe. On March 17, the patron saint of Ireland is celebrated in parades and festivals in surprising places such as Argentina, India, Japan, Singapore, Spain, Turkey, and the West Indies.

Although the celebration was launched by Irish people scattered all around the world to remember their Celtic heritage, now even non-Irish people claim to be “Irish for a day” – even if it is only a fun excuse to eat corned beef and cabbage, wear green, and order a Guinness. The vast majority of those celebrating have no idea who St. Patrick was or what he did. That is a pity.

Historians are constantly attempting to set the record straight. After all, Patrick was not Irish (born in Britain of a Romanized family). He was never canonized as a saint by the Catholic Church. Interestingly, there are two St. Patrick’s Cathedrals in Armagh, Ireland – one Catholic and one Protestant. Remarkably, Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin is connected to the Church of Ireland, but has both Catholic and Protestant clergy.

The legacy of Ireland’s patron saint blurs a lot of lines – but, he is notably worth celebrating.

Patrick was brutally abducted at the age of 16 by pirates and sold as a slave in Ireland. For six agonizing years in a foreign land, he largely lived in abject solitude attending animals. The Christian faith of his family that he found unappealing as a teenager became his spiritual lifeline to sanity and survival while in captivity.

“Tending flocks was my daily work, and I would pray constantly during the daylight hours,” he writes in his Confession – one of only two brief documents authentically from Patrick’s own hand. “The love of God and the fear of him surrounded me more and more – and faith grew and the Spirit was roused, so that in one day I would say as many as a hundred prayers and after dark nearly as many again even while I remained in the woods or on the mountain. I would wake and pray before daybreak – through snow, frost, rain – nor was there any sluggishness in me (such as I experience nowadays) because then the Spirit within me was ardent.”

Through a divine dream, Patrick was inspired to make his escape. His journey as a fugitive was, according to his testimony, a 200 mile trek to the coast. Further miraculous circumstances allowed him to wrangle himself aboard a ship to escape his imprisonment in Ireland. He finally made it back to the loving embrace of his family.

Years later, however, another mystical dream launched his trajectory into the ministry and, ultimately, back to Ireland. “We appeal to you, holy servant boy,” said the voice in the dream, “to come and walk among us.”

For many years, he trained to become a priest. Eventually, in 432 A.D., Patrick returned to the shores of the land where he once was held captive.

“Believe me, I didn’t go to Ireland willingly that first time [when he was taken as a slave] – I almost died there,” he wrote in his Confession. “But it turned out to be good for me in the end, because God used the time to shape and mold me into something better. He made me into what I am now – someone very different from what I once was, someone who can care for others and work to help them. Before I was a slave, I didn’t even care about myself.”

Noted classics scholar Philip Freeman, the author of St. Patrick of Ireland, points out the distinguished uniqueness of Patrick’s public vulnerability – a trait that was not characteristic of a man of his stature and notoriety. As an elderly and well-known bishop, Patrick begins his Confession with these words: “I am Patrick – a sinner – the most unsophisticated and unworthy among all the faithful of God. Indeed, to many, I am the most despised.”

“The two letters are in fact the earliest surviving documents written in Ireland and provide us with glimpses of a world full of petty kings, pagan gods, quarreling bishops, brutal slavery, beautiful virgins, and ever-threatening violence,” writes Freeman. “But more than anything else, they allow us to look inside the mind and soul of a remarkable man living in a world that was both falling apart and at the dawn of a new age. There are simply no other documents from ancient times that give us such a clear and heartfelt view of a person’s thoughts and feelings. These are, above all else, letters of hope in a trying and uncertain time.”

While there are many beautiful, miraculous, and fantastical stories about St. Patrick, his Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus – the other document authentically written by Patrick – exposes his heart and soul. It portrays the character of a man worthy of emulation and celebration. His humility, empathy, and righteous indignation scorches the letter as he takes up the cause of the voiceless captives and powerless victims of slavery – a common practice in the fifth century.

The fiery correspondence addresses the horrific news that a group of newly baptized converts were killed or taken into slavery on their way home by a petty British king named Coroticus, known to be at least nominally a Christian.

“Blood, blood, blood! Your hands drip with the blood of the innocent Christians you have murdered – the very Christians I nourished and brought to God,” Patrick writes. “My newly baptized converts, still in their white robes, the sweet smell of the anointing oil still on their foreheads – you murdered them, cut them down with your swords!”

Violating cultural and ecclesiastical protocols, the letter was sent broadly and caused a stir. Courageously, Patrick launched a public ruckus – outside his governance – over the “hideous, unspeakable crimes” because he believed that God truly loved the Irish – even if church leaders elsewhere did not. Patrick’s vision for the love of God was expansively generous. “I am a stranger and an exile living among barbarians and pagans, because God cares for them,” he writes (emphasis added).

“Was it my idea to feel God’s love for the Irish and to work for their good?” Patrick writes. “These people enslaved me and devastated my father’s household! I am of noble birth – the son of a Roman decurion – but I sold my nobility. I’m not ashamed of it and I don’t regret it because I did it to help others. Now I am a slave of Christ to a foreign people – but this time for the unspeakable glory of eternal life in Christ Jesus our master.”

Having been captive, he does not write about slavery whimsically. He was an outspoken voice opposing slavery at a time when it was simply considered commonplace. Furthermore, he was a fierce advocate for those who were most vulnerable and abused in captivity.

“But it is the women kept in slavery who suffer the most – and who keep their spirits up despite the menacing and terrorizing they must endure,” he writes in his Confession. “The Lord gives grace to his many handmaids; and though they are forbidden to do so, they follow him with backbone.”

When Patrick heard about the bloody attack and abductions after the baptism service, he sought to reason with Coroticus: “The very next day I sent a message to you with a priest l had taught from childhood and some other clergy asking that you return the surviving captives with at least some of their goods – but you only laughed.”

In response, Patrick derides Coroticus and his men as “dogs and sorcerers and murderers, and liars and false swearers … who distribute baptized girls for a price, and that for the sake of a miserable temporal kingdom which truly passes away in a moment like a cloud or smoke that is scattered by the wind.”

In order to make his point, he prays: “God, I know these horrible actions break your heart – even those dwelling in Hell would blush in shame.”

With pastoral care, Patrick addresses the memory of those killed after their baptism: “And those of my children who were murdered – I weep for you, I weep for you … I can see you now starting on your journey to that place where there is no more sorrow or death. … You will rule with the apostles, prophets, and martyrs in an eternal kingdom.”

Even in an inferno of justifiable rage, Patrick extends an olive branch of redemption: “Perhaps then, even though late, they will repent of all the evil they have done – these murderers of God’s family – and free the Christians they have enslaved. Perhaps then they will deserve to be redeemed and live with God now and forever.”

“The greatness of Patrick is beyond dispute: the first human being in the history of the world to speak out unequivocally against slavery,” writes historian Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization. “Nor will any voice as strong as his be heard again till the seventeenth century.”

All around the globe, St. Patrick’s Day is set aside to honor a great man who overcame fear with faith, overcame hate with love, and overcame prejudice with hope. Although he had every reason in the world to resist the dream to return to “walk among” the Irish, Patrick responded to the God-given impulse of his heart – even when it was most difficult. He knew the dangers and challenges and returned anyway.

Patrick offered himself as a living example of what new life could look like for the Irish. “It is possible to be brave – to expect ‘every day … to be murdered, betrayed, enslaved – whatever may come my way’ – and yet be a man of peace and at peace, a man without sword or desire to harm, a man in whom the sharp fear of death has been smoothed away,” writes Cahill of Patrick. “He was ‘not afraid of any of these things, because of the promises of heaven; for I have put myself in the hands of God Almighty.’ Patrick’s peace was no sham: it issued from his person like a fragrance.”

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of Good News. Artwork by Winfield Bevins. Used by permission.

by Steve | May 27, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May/June MJ 2021

Photo by Haley Rivera (Unsplash).

By Andrew C. Thompson –

John Wesley met with a group of Methodist preachers in London for a watch-night service on February 6, 1789. It was just two years before his death, and Wesley was an old man. Yet age and infirmity did not hinder him from impressing upon his young followers what he had been teaching for over half a century.

As he records in his journal, “I strongly insisted on St. Paul’s advice to Timothy, ‘Keep safe that which is committed to thy trust,’ particularly the doctrine of Christian Perfection which God has peculiarly entrusted to the Methodists.”

It is that conviction of Wesley’s around the importance of the doctrine of Christian perfection that drives Kevin M. Watson’s newest book, Perfect Love: Recovering Entire Sanctification – The Lost Power of the Methodist Movement (Seedbed).

Watson is a prolific author whose scholarly focus is on John Wesley, early British Methodism, and the later American Methodist tradition. He has produced well-regarded academic monographs on the history of the early Methodist band meeting in the 18th century and the American Methodist tradition in the 19th century. Yet he is best known to many people as a writer with a passion for bringing neglected practices of early Methodism into present-day, practical discipleship. His first book for a general reading audience was A Blueprint for Discipleship (Discipleship Resources), which still stands as the best treatment of how to appropriate John Wesley’s General Rules in the present.

Perhaps his best-known popular-level work is The Class Meeting (Seedbed), a book that has been used by hundreds if not thousands of congregations to start class meetings in their own local churches. Most recently, he co-authored The Band Meeting with Scott Kisker (Seedbed) where he and Kisker introduced early Methodist band fellowship to contemporary Methodists.

Watson’s newest book Perfect Love looks not at an early Methodist practice but rather at an early Methodist idea. That idea is Christian perfection, or entire sanctification. It is the conviction that we can by grace be made holy in heart and life to the extent that the power of sin is utterly overcome in our lives. Positively speaking, it is the idea that we can be so filled with the love of Jesus Christ that that love animates our every thought, desire, word, and action.

Watson’s newest book Perfect Love looks not at an early Methodist practice but rather at an early Methodist idea. That idea is Christian perfection, or entire sanctification. It is the conviction that we can by grace be made holy in heart and life to the extent that the power of sin is utterly overcome in our lives. Positively speaking, it is the idea that we can be so filled with the love of Jesus Christ that that love animates our every thought, desire, word, and action.

It’s also an idea that goes by a variety of names drawn from the Bible and the Wesleyan tradition: Christian perfection, entire sanctification (the term Watson prefers), full salvation, perfect love, and other variations on these. The most common term used to describe it has often been seen as the most objectionable: “perfection.” The connotation that perfection has when applied to our discipleship can seem negative for obvious reasons. It suggests that we can attain a quality that is only available to God; or conversely, it smacks of a certain arrogance by people who perhaps do not fully grasp the depth of human sinfulness.

Yet Wesley believed that perfection was not only possible but the very goal of the Christian life. His passion for teaching about entire sanctification is one that Kevin Watson has embraced as well. As Watson says in his opening chapter, “Entire sanctification is the doctrine that defines Methodism’s audacious optimism that the grace of God saves us entirely to the uttermost.” Wesley once wrote in a letter to R.C. Brackenbury that “full sanctification … is the grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called Methodists; and for the sake of propagating this chiefly He appeared to have raised us up.” It is a point Watson returns to repeatedly throughout the book, contending that a renewed focus on entire sanctification is the key to revival within the Methodist movement.

Watson makes his case for the importance of the teaching of entire sanctification by pointing to a number of examples from the 18th and 19th centuries of people who testified to having experienced perfection. Here, Watson’s historical facility with the Methodist tradition is on full display as he moves easily from figures like Jane Cooper and John Fletcher to Phoebe Palmer and B.T. Roberts. Though Watson doesn’t say so explicitly, one of the strengths of the examples he uses is the way the various characters reflect such broadly different backgrounds and experiences. His examples run the gamut from learned theologians to frontier preachers, and from sophisticated urbanites to roughhewn rural folk. All of them had experiences of God’s perfecting grace, and they shared a common spirituality that made up the beating heart of the Methodist revival on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yet common experience is not enough to embrace any given teaching; it must be grounded in God’s will for his people as revealed in the Bible. This, in fact, is exactly why Wesley insisted on perfection. He did not believe that perfection was a novel teaching. As Watson ably points out, Wesley believed it should be taught because he believed that it was rooted in the Scriptures. The words “holiness” and “sanctification” are synonyms of one another, and the spiritual reality towards which they point is the goal of the Christian life as we find it taught in the Bible. The phrase that Wesley used to sum up what it means to live in this way is “holiness of heart and life.” When we are transformed inwardly (the heart), then our outward life will follow. That transformation is always a transformation in Christ’s love, and it is that love that defines what holiness is.

Watson does a wonderful job in explaining many of the particular characteristics around the Wesleyan teaching on entire sanctification. One is that sanctification (like justification) always comes by faith and not by works. And the surest way to receive it is to seek after it in prayer.

A second characteristic is the way in which Wesley spoke about entire sanctification as coming both gradually and instantaneously. This is one of the more confusing aspects of Wesley’s view of perfection, and it can perhaps best be understood with reference to the way that a race is both run and completed. You always finish a race in an instant (which is the instant you cross the goal line). But you are gradually drawing close to that final instant with every step that you take. This is Wesley’s view of perfection, except you have to add one extra layer. For Wesley, it’s also as if the race is constantly going around new turns, and the goal line could suddenly pop up on the other side of any one of them. Just so, the gradual growth in grace could culminate in perfection at any moment for the earnest Christian.

Finally, a third characteristic that Watson highlights is simply what perfection does not entail. It does not mean that we are free from ignorance, mistake, infirmity, or temptation. It doesn’t even mean we are free from the possibility of falling back into sin. What it does mean is that we are really and truly free from sin right now. And that includes not only the commission of actual sins, but also any sinful thoughts and affections of our hearts.

How, then, do we pursue perfection in practical sense? Here, Watson’s previous work on early Methodist practices serves him well in describing the spirituality of a Christian believer who is yearning for entire sanctification. He mentions more than once the importance of embracing the General Rules in the day-to-day lives of Methodist folk (do no harm, do all the good you can, and attend upon the ordinances of God). He also points to practicing the means of grace given by God to draw us closer to Christ and experience his sanctifying grace (prayer, searching the Scriptures, the Lord’s Supper, fasting, and Christian conference). Finally, he emphasizes the importance of the band meeting as the original small-group structure in early Methodism that was meant to help people reach entire sanctification through mutual confession of sin, testimony, and intercessory prayer.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Wesleyan teaching on Christian perfection is that it is never a static experience. Indeed, there is no sense at all in Wesley’s view that you ever reach a point where you can no longer grow in God’s love. “A person who experiences entire sanctification is still on a journey,” Watson writes. Such a person will “still need to grow daily in grace.” There is a sense in Wesley’s writing that God’s sanctifying grace can continue to draw us into fuller communion with Christ Jesus even after the battle with sin has been won.

In A Plain Account of Christian Perfection, Wesley asks the question, “Can those who are perfect grow in grace?” And then he provides the answer: “Undoubtedly they can; and that not only while they are in the body but to all eternity.” Such an affirmation means that the Wesleyan teaching on Christian perfection pertains not only to discipleship in this present life, but to our enjoyment of God in the life to come.

The strengths of Perfect Love are significant indeed. Given its central importance to John Wesley’s understanding of the Christian life, it is remarkable that a book like this has not appeared sooner. (Watson points out how attention to perfection was not only neglected but actively opposed in American Methodism of the late 19th century, and in that sense this book is long overdue!) There are a few areas that a reader might be left wanting a bit more, however. Watson nods to the relationship between justification and sanctification at a couple of points, but people more familiar with the former than the latter will be left with questions about how one is to think about the connection between the two. Also missing is any attention to Wesley’s theological influences outside of Scripture, other than the briefest of mentions about his engagement with the holy living tradition (e.g., Thomas à Kempis, Jeremy Taylor, and William Law).

Part of the formative influence on Wesley for Christian perfection came from the early church fathers – perhaps most especially Clement of Alexandria, whom he cited in print as an inspiration for how he came to think about perfection. Wesley (as Watson points out) was fundamentally interested in entire sanctification because he believed it was thoroughly biblical. Yet he was also working from a broader tradition (known as theosis or divinization in the early church tradition) in this as in so much else in his theology.

Dr. Andrew C. Thompson

Like Watson’s other popular-level works, Perfect Love is written with tools to help individuals and small groups fully engage the text. Each chapter concludes with a discussion guide that offers both a format for small group meetings and sample questions for discussion. Watson has also included a number of appendices with primary source materials for readers who want to dig into some of the original Wesleyan and Methodist texts on sanctification: the General Rules, Wesley’s sermon, “On Christian Perfection,” Wesley’s sermon, “The Scripture Way of Salvation,” the Rules of the Band Societies, and a sampling of doctrinal statements from denominations descended from early Methodism.

One of Watson’s greatest strengths is his ability as a writer. Not all brilliant academics are able writers for a broad reading audience, but Watson has that talent in spades. His writing style in Perfect Love is almost conversational, and any engaged reader will find it accessible. For Methodists today who are interested in the biblical teaching that John Wesley believed was the most important gift the Methodist movement could offer to the Christian church, Perfect Love is the perfect book. Watson no doubt would hope that readers would pick it up not just wanting to learn about entire sanctification, but wanting to experience it for themselves.

Andrew Thompson is senior pastor of the First United Methodist Church of Springdale, Arkansas, and the author of The Means of Grace and Watching From the Walls.

by Steve | May 27, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May/June MJ 2021

“Methodism exists in order to preach, teach, and proclaim the bold optimism that the grace of God is able to bring full salvation to everyone.”

By Kevin M. Watson –

Methodism is in the midst of an identity crisis. We have forgotten who we are. We have abandoned our theological heritage.

God raised up the people called Methodists to preach, teach, and experience one core doctrine. This doctrine is Methodism’s reason for existence. If we get this right, everything else will fall into place. If we get it wrong, we will miss the unique calling and purpose that God has for us.

Less than six months before he died, John Wesley wrote a letter to Robert Carr Brackenbury that referred to this core doctrine as “the grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called Methodists; and for the sake of propagating this chiefly He appeared to have raised us up.”

That sounds important! But the previous quotation also contains a handful of words that we do not use much today. Let’s start with “grand depositum.” Wesley meant that God had deposited or entrusted Methodism with something of great worth and importance. Propagating means to spread or pass on to others.

So, Wesley was saying that God had entrusted Methodism with something specific of great worth and importance. And God raised up Methodism in order to spread what God has entrusted to us to as many other people as possible.

Wesley identified the key thing that God gave to Methodists as a specific doctrine or teaching. So, what is this doctrine? Entire sanctification or Christian perfection is the grand depositum that God has given to us.

Entire sanctification is the doctrine that defines Methodism’s audacious optimism that the grace of God saves us entirely, to the uttermost.

This grand depositum is still the reason God raised up Methodists. Methodism exists in order to preach, teach, and proclaim the bold optimism that the grace of God is able to bring full salvation to everyone. Methodism separated from this core teaching has no future. If Methodism focuses once again on this grand depositum, it will find new life and fresh outpouring of the Holy Spirit in its midst.

We have the opportunity to recover this powerful truth and again present it to a world desperate for hope and healing.

This discussion is for everyone who at some point traces their spiritual lineage back to John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. This includes denominations that have the word Methodist in their names, such as the United Methodist Church or the African Methodist Episcopal Church. I also have members of the Holiness Movement in mind, like the Wesleyan Church, the Free Methodist Church, Church of God (Anderson), Church of the Nazarene, and the Salvation Army. But this is still not the full extent of the Methodist family. I am also thinking of members of the global Pentecostal movement whose understanding of a second work of grace and baptism of the Holy Spirit can be traced back to John Wesley and the doctrine of entire sanctification. When Pentecostalism is taken into consideration, we are talking about well more than a billion (yes, billion with a “b”) Christians today who can trace their heritage back to Wesley and early Methodism.

Methodism’s significance within the body of Christ is often underestimated or overlooked. But we are a powerful movement of the Holy Spirit that has brought not only forgiveness of sins through faith in Christ, but also freedom from the power of sin and an outpouring of holy love in countless lives over the past three centuries. Methodism has been the most Spirit-filled in our history when people have leaned into our grand depositum and wrestled with God to help people receive the blessing of entire sanctification. When Methodists have lowered their expectations of what God can do in this life, spiritual and numeric decline have followed.

God did not raise us up to lower expectation for what is possible through the work of Jesus Christ. We have been brought to life to tell the world that “it is God’s will that you should be sanctified” (1 Thess. 4:3a). And God is able to do what he wants to do in us!

Why Are We Here? These are trying times for Wesley’s spiritual heirs. All who trace their spiritual lineage back to John Wesley are facing sustained challenges in a variety of ways. Despite these real and serious challenges, I feel excitement and a growing sense of anticipation.

I have an expectation in my spirit that the living God is going to do an (old) new thing. Unsettled and even chaotic times can provide an opportunity for reevaluation. They can bring clarity. Difficult seasons can bring renewed focus on the reason a group exists. This is a great time to seek clarity about a basic question: Why are we here?

I am convinced that there is one main reason we exist: to preach, teach, and help people receive the gift of entire sanctification. This is the reason God first breathed life into Methodism. And this is the reason I have hope God will breathe life into our churches once again.

Like many of you, I’ve been praying. I’ve been asking God to break through. I’ve been wrestling with what faithfulness looks like in this time and in this place. And I’ve been hearing the word “return.” The first time I heard that word, my mind was going in so many different directions I wasn’t sure what it meant. But as I’ve kept hearing “return,” the mist and confusion have been clearing away and one particular Scripture passage has stood out:

Thus says the LORD:

Stand at the crossroads, and look,

and ask for the ancient paths,

where the good way lies; and walk in it,

and find rest for your souls.

But they said, “We will not walk in it.” (Jeremiah 6:16, NRSV)

It is time for the people called Methodists and all of John Wesley’s spiritual heirs to return to the ancient path that Wesley referred to as the “grand depositum” of “the people called Methodists.” Lest we respond like those who heard Jeremiah: “But they said, ‘We will not walk in it.”

The grand depositum of Methodism was the doctrine of entire sanctification, or Christian perfection. The mission of Methodism in Britain and in the United States was initially to “spread scriptural holiness.” Holiness, or sanctification, was the core focus and purpose of the people called Methodists. Wesley understood holiness to be an ongoing process of becoming more and more like Jesus, loving God and neighbor to the exclusion of sin. Entire sanctification (which will also be referred to as Christian perfection or full salvation here) was the goal of ongoing growth in holiness. So, what exactly is entire sanctification? In A Plain Account of Christian Perfection, Wesley gave a succinct definition:

“(1) That Christian perfection is that love of God and our neighbor, which implies deliverance from all sin. (2) That this is received merely by faith. (3) That it is given instantaneously, in one moment. (4) That we are to expect it, not at death, but every moment; that now is the accepted time, now is the day of this salvation.”

The goal for Wesley and his followers was to actually live the kind of life that Scripture tells us is possible by the grace of God in Christ Jesus. This determination was expressed most boldly in the doctrine of entire sanctification. This teaching was the grand depositum that God gave to Wesley and those who went before us.

It is time to return, to recommit to steward what has been entrusted to those who follow in the footsteps of Wesley and the first Methodists.

Dr. Kevin M. Watson

The Stakes Are High. I am convinced that any form of Methodism that is not dearly connected to the doctrine of entire sanctification has no future. Any new movements or expressions of Methodism must place our grand depositum at the center of our faith and practice. I am equally convinced that if we as a people recommitment ourselves to this grand depositum, God will breathe new life into our movement out of love for a desperate and hurting world.

Here is what I see as being at stake for us today: We live in a world where many are desperate for hope and healing. Many have a quiet desperation that comes from the numbness and pseudo connections that have developed from spending too much time connected to our screens and far too little time connecting in person in life-giving relationships. Many are desperate because they know that their lives are going in directions that are not going to end well, but they are not able to stop. Many are depressed, discouraged, and simply without hope. The list could go on.

In this reality, our calling is to preach the full gospel. We have the good news of Jesus Christ. The gospel of Jesus not only brings forgiveness and pardon; the gospel brings hope and healing. Through faith in the amazing grace of God, we can be forgiven and reconciled to God. This is, indeed, good news. But there is more! God doesn’t want to just forgive us, he also wants to offer us power and freedom over the ways of sin and death.

We need not limp through this life, defeated, merely surviving. No! “We are more than conquerors through him who loved us” (Romans 8:37 NRSV)!

We can be saved to the uttermost!

Jesus is able. There should not be a church in any of our communities that has a more audacious and bold optimism of what God’s grace can do in the lives of every single person than churches that trace their roots back to John Wesley. Entire sanctification is not an abstract idea or merely a theory.

Not at all!

Entire sanctification is the fruit that comes from knowing a person – Jesus, our risen Lord. Jesus saves. Jesus rescues. Jesus heals. He has done these things before and he will do them again!

There is still Living Water here.

As we unplug the well of the entire sanctification and invite people to drink deeply from it, we will see fruit. We will see lives undone by the love of God that has been poured out over the world in Jesus Christ. We will see lives mended and made whole. We can unplug this well now and offer the Water that is already in it today to the people in our communities.

Kevin M. Watson is associate professor of Wesleyan and Methodist Studies at Candler School of Theology, Emory University in Atlanta. He is the author of numerous books, including The Class Meeting (Seedbed). This article is taken from his recent book Perfect Love: Recovering Entire Sanctification – The Lost Power of the Methodist Movement (Seedbed, 2021). It is reprinted by permission. He writes at kevinmwatson.com.

by Steve | May 27, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May/June MJ 2021

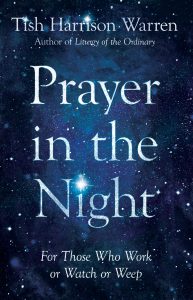

The Rev. Tish Harrison Warren

By Elizabeth Glass Turner –

There is a point when dog-earing a book becomes an exercise in futility. My copy of Tish Harrison Warren’s Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep is accordioned with an absurdly unhelpful number of dog-eared pages.

The Anglican priest and author constructed a kind of catechism of grief just before the world slipped into isolated chaos in 2020. Borne in on the wake of her own annus horribilis – in 2017, she moved halfway across the country, lost her father suddenly, and lost two sons to miscarriage – Prayer in the Night is fashioned from an entry in the Book of Common Prayer that sustained her in the wreckage.

If you are shipwrecked, the book is a first-aid kit, an emergency ration box, and Warren patiently tutors the reader in the usefulness of each component with the clear-eyed pathos of someone who has hungered through long nights waiting for a rescue plane that might or might not come. She is unflinching.

Some might wonder if a book with the word “weep” in the subtitle can find a place on shelves just as likely to be lined with resources on church growth, self-improvement, leadership, vision, or other ways to optimize potential and stay ahead of everyone else. For several decades, faith-based publishing has been nothing if not optimistic. Do most people really want to read about those who work and watch and weep?

A couple of things are noteworthy. It is rare for a faith-based author on social media to receive comments from multiple readers sharing that they’d personally purchased boxes of copies to distribute to colleagues, friends, and family members, as Warren has received. Further, Prayers in the Night might normally be a valuable book likely to fly under the radar. (The human instinct to plug our ears in denial of mortality runs deep.) However, Warren happened to finish it just weeks into a nascent pandemic; it was released as the global toll of that pandemic continued to rage. What the author could not know when she began writing was that the world was about to be hit with a once-in-a-generation occurrence, with many people about to lose the luxury of putting mortality on mute.

A couple of things are noteworthy. It is rare for a faith-based author on social media to receive comments from multiple readers sharing that they’d personally purchased boxes of copies to distribute to colleagues, friends, and family members, as Warren has received. Further, Prayers in the Night might normally be a valuable book likely to fly under the radar. (The human instinct to plug our ears in denial of mortality runs deep.) However, Warren happened to finish it just weeks into a nascent pandemic; it was released as the global toll of that pandemic continued to rage. What the author could not know when she began writing was that the world was about to be hit with a once-in-a-generation occurrence, with many people about to lose the luxury of putting mortality on mute.

By the Eucharistic grace of God, Warren had offered up what she had on hand: her tragedy, like a child holding up some bread and fish. She wrote what she found to be true and useful during her long, dark night of the soul. In the economy of God’s grace, what she gave freely is feeding more people than she could have anticipated. Her own words speak to what loss requires: “I needed words to contain my sadness and fear. I needed comfort, but I needed the sort of comfort that doesn’t pretend that things are shiny or safe or right in the world. I needed a comfort that looked unflinchingly at loss and death. And Compline is rung round with death.”

In part a primer on prayer, in part a primer on what it means to be human, the chapters are organized as a steady unpacking of the phrases of a Compline prayer, part of the bedtime reading of the Daily Office in the Book of Common Prayer:

“Keep watch, dear Lord, with those who work, or watch, or weep this night, and give your angels charge over those who sleep. Tend the sick, Lord Christ; give rest to the weary, bless the dying, soothe the suffering, pity the afflicted, shield the joyous; and all for your love’s sake. Amen.”

Warren unloads these phrases with pragmatic depth, rendering a resource that is sure to be used in study (as the discussion questions at the back provide for). But it is not first and foremost a study, unless it is a study of loss and the nature of a God who allows it. Sometimes in the shellshock of grief, we don’t know how to talk to a God we’re angry at; we don’t have energy to form our own words. But at the outset, the author shares her experience of learning the value of the practices and prayers of the ancient church in times of crisis and catastrophe.

“I’ve come to believe that … to sustain faith over a lifetime, we need to learn different ways of praying,” she writes. “Inherited prayers and practices of the church tether us to belief, far more securely than our own vacillating perspective or self-expression.” For seasons of profoundly disorienting loss, she compares the prayers of the church to cairns marking a foggy mountain path. “When I could not pray, the church said, ‘here are prayers.’ When I could not believe, the church said, ‘come to the table and be fed.’ When I could not worship, the church sang over me the language of faith.”

The prayers to which the author calls us are not just life rafts or escape hatches; regularly, she reminds the reader that prayer shapes and forms us. “Faith is more craft than feeling. And prayer is our chief practice in the craft. We are given means of grace that we can practice, whether we feel like it or not, and these carry us. Craftsmen – writers, brewers, dancers, potters – show up and work, and they participate in a mystery. In our deepest moments of darkness, we enter into this craft of prayer. Patterns of prayer draw us into the long story of Christ’s work in and through his people over time.”

As Warren unfolds the Compline prayer phrase by phrase, the path of grief is illuminated as spiritual formation. She scoots among the commonplace and the ancient, quoting “Almost Famous” then unpacking apophatic theology with approachable ease. Not everyone can briefly sketch theodicy or apophatic theology with simplicity. Yet she manages to do so, deftly demonstrating how idea and practice merge, revealing the value of theological treasures left in the dusty attic of church history. Her voice is like an Antiques Roadshow appraiser, surprising us with the hidden value of what we unknowingly pass by – only the worth is not only convenient, it’s life-saving. The reader is shown with pressing clarity how and why this prayer matters for you, today, and how it can shape the worst moments of the worst days of your life. There is no sugar-coating; no prosperity gospel; no platitudes. But there is honesty, joy, and hope.

In Prayer in the Night, there is little that is casual, much that is accessible. Loss can clarify voice (eventually); the frank, easy tones found in Warren’s previous book, Liturgy of the Ordinary, are familiar yet carry a new sense of urgency, as though the matter is life and death: because it is.

“Compline,” writes Warren, “speaks to God in the dark. That’s what I had to learn to do – to pray in the darkness. When we’re drowning we need a lifeline, and our lifeline in grief cannot be mere optimism that maybe our circumstances will improve because we know that may not be true. We need practices that don’t simply palliate our fears or pain, but that teach us to walk with God in the crucible of our own fragility.”

Instinctively, whatever circumstances the reader currently finds themselves in, it is easy to recognize that our world does not crave “mere optimism.” If, as Warren outlines in chapter three, we allow ourselves to grieve and lament individually and together as a church, we may travel through to substantive hope on the other side; but grief must come first. On the value of praying the Psalms, she notes, “If our gathered worship expresses only unadulterated trust, confidence, victory, and renewal, we are learning to be less honest with God than the Scriptures themselves are.”

Warren’s potent phrasing is scattered throughout, unlikely as an inspirational slogan slapped on overpriced merchandise, but more likely to help preserve your faith in the dark night of the soul. (There are always trade-offs in life.) Exploring the phrase, “tend the sick, Lord Christ,” Warren wryly plumbs the human discomfort with frustration and physical frailty. “A lot of what appears as kindness or patience or holiness in my life is fueled by good health, energy, and simple pleasures. When these are taken away, it’s clear that I am not that kind or patient after all. I just didn’t have back pain.” Sanctification stings.

But there is no use mincing words when you’re in the crucible. When Warren swats away common theological and philosophical insufficiencies (she gives readers the dignity of engaging hard questions), she does so with vivid insistence. “I have come to see theodicy as an existential knife-fight between the reality of our own quaking vulnerability and our hope for a God who can be trusted.” Warren points the heartbroken reader to the tender heart of God. “The church has always proclaimed that if we want to see what God is like, we look to Jesus – a man ‘acquainted with sorrow,’ no stranger to grief, a peasant craftsman who knew suffering, big and small, and died a criminal, mostly alone. Mysteriously, God does not take away our vulnerability. He enters into it. Jesus left a place where there is no night to enter into our darkness.”

After sitting in the darkness with each group called out in the Compline prayer – exploring what it means to work, watch, or weep; unfolding the reality of those who sleep, the sick, the weary, the dying, the suffering, the afflicted, the joyous – where is the reader led? “And all for your love’s sake.” Alluding to the speed of light in a vacuum as a universal constant, Warren proclaims, “we enter the practice of prayer in response to the steady fact that we are already loved. God’s love and devotion to us, not ours to him, is the source of prayer. He is the first mover in prayer, the one who has been calling to us before we could ever call to him. And he will not stop calling, no matter how dark the night becomes. Light, not darkness, is the constant.”

Warren continues the shift from gutted lament to battle-worn, hoarse doxology: “Our love is more akin to day and night. God’s love is a constant … the speed of light. His love is the center of all things and there is no darkness in it. The love of God – not sickness or weariness or death or suffering or affliction or joy – is the fixed center of our lives and eternity.”

In Madeleine L’Engle’s coming-of-age story on death and grief, A Ring of Endless Light, the teenaged Vicky Austin, shaken by a traumatic experience, talks with her dying grandfather.

“You have to give the darkness permission,” he tells her. “It cannot take over otherwise. … Vicky, do not add to the darkness.”

There at the hospital bed, she both heard him and did not hear him.

“Vicky, this is my charge to you,” her grandfather continued. “You are to be a light bearer. You are to choose the light.”

“I can’t…” Vicky whispered.

“You already have,” he said. “But it is a choice which you must renew now.”

She couldn’t speak.

“I will say it for you,” her grandfather said. “You will bear the light.”

In her loss, Warren, a priest, has chosen the role of acolyte, choosing to be a lightbearer. Like Vicky’s grandfather, the Compline prayer tells the crumpled believer, “I will say it for you,” when the darkness has stolen our words. In hollow contrast to the arrival of spring, the darkness of loss threatens to suffocate many in our nation and our churches, and Prayer in the Night comes at a critical moment, naming the darkness, bringing the light near, and showing us how to be light-bearers.

Elizabeth Glass Turner is a frequent and valued contributor to Good News. She is the managing editor of Wesleyan Accent (wesleyanaccent.com).

by Steve | May 27, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May-June 2021

Thomas Lambrecht

By Thomas Lambrecht –

The dust is clearing after an eventful last few months for The United Methodist Church. General Conference is postponed in-person to August 2022. A special virtual General Conference was scheduled for May 8, 2021, and then canceled.

The new Global Methodist Church has been unveiled as denomination information – to be formally inaugurated following the anticipated enactment of the Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace through Separation at an upcoming General Conference.

The desire to hold a virtual General Conference in May demonstrated how “stuck” the church currently is. The Commission on the General Conference concluded it could not hold a General Conference virtually because it would rule out equitable participation by all delegates around the world, particularly in Africa and the Philippines. Yet, the Council of Bishops felt the need to call a virtual General Conference despite that anticipated inequity.

The Judicial Council had to formulate church law (not their responsibility) in order to save the administrative process allowing the church to deal with ineffective clergy and clergy unable to fulfill their duties, after the Council had ruled that process unconstitutional. Bishops that are required to retire under the Book of Discipline cannot retire because their jurisdictional or central conference cannot meet. General, jurisdictional, and central conferences are not empowered to meet virtually in extraordinary circumstances. There is no way to change the quadrennial budget if the General Conference cannot meet to do so.

Therefore, the church continues to operate under the 2017-2020 budget, which is obsolete. Certain annual conference officers cannot be elected until after the General Conference meets. These and other decisions await the opportunity for General Conference to meet, and they show how the church is “stuck” in the meantime.

What about the Protocol for Separation? The Council of Bishops’ agenda for the special virtual General Conference did not include the Protocol. Yet the biggest obstacle to getting the church “unstuck” is the decision about moving forward with separation. If the General Conference approves of separation, then conferences and churches can move forward with their decision about how they want to align themselves. If the General Conference does not approve of separation, then the church would return to the state of elevated conflict seen during and after General Conference 2019.

Acting on administrative matters, but not the Protocol, might get the church “unstuck” administratively, but it would not get the church “unstuck” in the larger sense. We would continue to live in uncertainty, unable to effectively invest in expanded ministry and unsure of our future identity. This is not healthy.

It would be far better to deal with the big decision on separation early, so that all the other decisions to be made in the future could flow from that one.

- What should the budget be for the current quadrennium and into the years beyond? That depends upon whether separation occurs and how many churches and members align with a new denomination.

- How many bishops should we elect in 2022 (or whenever episcopal elections become possible)? That depends upon how many annual conferences remain in The United Methodist Church and what their financial capacity is.

- Should we elect five new bishops in Africa, as promised in 2016? That depends on how many African annual conferences remain in the UM Church or go with the Global Methodist Church, and what is the financial capacity of the UM Church after separation.

- What will be the annual conference boundaries? That depends upon how many local churches remain in each region. Annual conference boundaries will likely need to be redrawn in some cases by the jurisdictional or central conferences when they are able to meet.

- How many general church boards and agencies do we need and how should they be structured? That depends upon how many people remain in the UM Church and the financial capacity of the remaining denomination.

- How many seminaries can the UM Church sustain? That depends upon how many students are likely to go into ministry in the church and how many churches remain as potential places to serve.

These and many other decisions flow from the one big decision about separation. The Council of Bishops envisioned at least some of these decisions taking place in virtual jurisdictional and central conference meetings later in 2021, which now may not be possible. But those decisions would be shots in the dark if we have not decided about separation.

As the Council of Bishops engages in “deep listening” – their phrase – and attempts to discern “a new timeline” leading up to the next General Conference, they should formulate a way for the General Conference delegates to consider and act upon the Protocol at the earliest possible time.

An Emerging Concern. I have concerns about the viability of an August 2022 in-person General Conference. Current vaccination information coming out of Africa is that some parts of the continent will be less than half vaccinated by the middle of 2023! Unless the pace of supply and distribution of vaccines picks up dramatically, it will not be possible for African delegates to travel to the U.S. for a 2022 General Conference. Under that scenario, an in-person General Conference may not be possible until the scheduled conference in May 2024.

For the church to remain “stuck” for the next three years would present an untenable situation that would contribute to the further precipitous decline of the church in the U.S. and other areas. The longer the delay in acting on the Protocol, the more opportunities for bishops and cabinets to marginalize evangelical and traditionalist clergy and congregations in their annual conferences. We have had several reports that local pastors were discontinued by their district committee on ordained ministry because those local pastors were honest about their intention to align with the Global Methodist Church when such alignment is possible. We have had reports of local churches being closed when they inquired of their district superintendent how much they would have to pay if they decided to withdraw from the church prior to the Protocol passing.

The tenuous truce that currently exists, where no complaints are filed against partnered gay clergy or clergy who perform same-sex weddings, may be jeopardized by zealous progressive proponents victimizing traditionalist clergy and congregations. The longer we put off separating, the more likely the truce will unravel. The original moratorium proposed in the Protocol against the processing of complaints regarding LGBT clergy and weddings was only supposed to last five months until the Protocol was enacted. (Once it is enacted, there is no reason for traditionalists to file complaints, since they will be embarking to a new denomination.) But a five-month truce that turns into four years becomes a much more unstable situation that could jeopardize the spirit of calm that has characterized the past year of the church conflict.

It is up to the Council of Bishops and the Commission on the General Conference to begin planning now for the potential further postponement of General Conference beyond 2022 and setting in place the means for having a virtual General Conference that could address the Protocol.

What about Amendments to the Protocol? With a virtual General Conference, it is possible that there could be limited or no amendments to the Protocol and limited debate on the floor of General Conference. Given that the Protocol has been published and discussed publicly for over a year, it seems that the delegates ought to be familiar with its provisions. Additional communications could be prepared by the Protocol mediation group to further inform delegates of its provisions. A website has been available for over a year, with the Protocol agreement, the proposed legislation, frequently asked questions, and a PowerPoint presentation. They are available in all the official church languages. The resources are there to communicate the provisions of the plan.

There are some who would like to make changes to the provisions of the Protocol. If enough delegates want to entertain amendments, the Commission on General Conference could work out a way to do so. Alternatively, the delegates could decide to postpone action on the Protocol until an in-person General Conference becomes possible, even if it has to wait until 2024. However, the advantages of making the big decision on separation now in order to set the table for all the other following decisions outweighs any advantage that might be gained by the uncertainty of adopting amendments at a future date. Those proposed changes might not pass, and then we would have waited months or years for nothing. The grassroots laity in our church already believes this decision has been postponed far too long. Waiting will only reinforce that perception, no matter the good motives of those who want to postpone it.

Furthermore, the terms of the Protocol were negotiated in very rigorous and conflictual discussions. Each term was the result of a careful compromise between various viewpoints. For a majority of the delegates to change even one of the terms of the Protocol could jeopardize support for the whole package. While no one at the table thought the Protocol was perfect according to their perspective, all agreed that it is the best way to resolve our conflict and allow the church to get “unstuck.”

What about the Money? Some are concerned that the church might not be able to afford the provision that shares $25 million with a new traditionalist denomination and $2 million with other denominations that might form. While the apportionment income to the general church understandably fell in 2020, the financial provision was negotiated based on the church’s unrestricted reserve funds, not annual apportionments. While we do not yet know what amount remained in the church’s reserve at the end of 2020, the reserve was actually higher at the end of 2019 than when the Protocol was negotiated. We know that many of the boards and agencies received hundreds of thousands of dollars in PPP grants from the U.S. government in 2020. We also know that many of the boards and agencies have cut their staffs in order to adjust to lower expected apportionments in the years ahead.

The $27 million allocated to new denominations is not a “gift” from the UM Church to the new churches, but represents a proportional sharing of accumulated resources that were given by faithful United Methodists over the decades who will now serve the Lord in a different Methodist denomination. The money would be paid over four years, lessening the burden in any particular year. Its primary purpose would be to extend the church’s mission of making disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world in new Methodist expressions.

There are no compelling reasons at this time to change the financial provisions of the Protocol. And the ability to get the church “unstuck” and moving forward outweighs any potential benefit from having a fight about money on the General Conference floor.

Advantages for Centrists and Progressives. Many centrists and progressives have expressed frustration at their inability to move forward with their agenda for the church. Making the big decision on separation now would enable them to have a majority of the delegates to enact their program at the next in-person General Conference. If the Protocol is not enacted until 2022 or later, they may not be able to make the changes they desire until the 2024 General Conference or potentially even in 2028 (if the Protocol is not enacted until 2024).

Due to the moratorium requested in the Protocol, some annual conferences are currently ordaining practicing gays and lesbians to ministry and allowing same-sex weddings in local churches. However, other annual conferences are not doing so. Passing the Protocol now and subsequently removing restrictions from the Discipline would allow such ordination and weddings in all annual conferences that remain in The United Methodist Church.

Proponents of the Christmas Covenant and the Connectional Table regionalization plan hope to pass changes that would enable each geographic region of the church to govern its affairs in a more semi-autonomous fashion. Because those proposals need a two-thirds vote to pass, it is unlikely they would pass while traditionalists remain in the church. Passing the Protocol now would enable the next in-person General Conference to pass the regionalization plans and secure ratification, so they could be implemented more expeditiously.

Passing the Protocol would allow the centrist and progressive agendas for the church to move forward much more quickly than waiting until the next in-person General Conference. It would also allow the new denominations to form immediately and move forward in the new directions they envision. Most importantly, it would definitively end the theological conflict that is causing the UM Church to be “stuck.” The resulting churches would be truly “unstuck” and empowered to pursue ministry as they feel called by God.

Passing the Protocol is the only way to avoid protracted and expensive litigation, ensure that unfunded pension liabilities will be addressed, and enable the church to move beyond decades of conflict. Our church would be an example to a conflicted world that it is possible to settle disputes amicably and without winners and losers. Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers.” The Protocol is the way to peace in The United Methodist Church.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | May 27, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, May/June MJ 2021

Photo by Jonathan Portillo (Pexels).

By Shannon Vowell –

Spring pushing white and lavender and pink into dazzling prominence as the gray and brown disappear. Easter joy writ large on the landscape.

Alongside the greening, something new in my neighborhood, a winter-is-over ritual: Regiments of middle-school boys – hoodie-clad, bicycle-mounted, wielding iPhones and skateboards – are climbing up onto roofs.

Several were on the roof of the elementary school last week. Others have scaled fences to perch on backyard sheds. The online bulletin board is abuzz with worries and irritations about these boys and their exploits; the adult population not sure how to put a stop to these antics which are as fleeting and hard to anticipate as they are dangerous.

I have a soft spot for boys at the age and stage of these roof climbers. Look past the foul-mouthed bravura and there is something exquisitely poignant about their gangly, coltish limbs and downy cheeks. Boys on the brink of physical manhood are desperate to prove themselves brave and big and strong – and when big and strong are still out of reach, brave becomes the ultimate badge of honor.

Hence, roof climbing.

On a cloud-streaked afternoon, one of the boys managed to scale the gazebo in the park – a structure with multiple metal levels, whose top eaves are easily 25 feet high. He stood on the highest part of that roof – and then jumped! As high as he could! Skinny arms stretching into the somber sky!

I watched from my kitchen window with my heart in my mouth as his flimsy form silhouetted for a moment against late afternoon sunlight. For a split second, he was flying – Peter Pan or Icarus – all his boy-energy and aspiration physicalized in wild, ferocious defiance of gravity. It was piercingly beautiful, ballerina-grace and cheetah-speed compressed into a scruffy package and hurled into space.

Of course, it was also incredibly stupid and potentially fatal. But that roof-climber was safely down and escaping on his bike before I or any of the other adult witnesses could tell him so (or get his mom’s number to tattle on him).

I was profoundly relieved that he hadn’t fallen and broken himself on the concrete. I was also profoundly affected by the picture he had made, flung into thin air like that, daring the laws of physics to crack him like an egg. That gauntlet is thrown at death spotlighted life – in all its recklessness and risk and glory. It made me wonder: when was the last time I felt completely alive?

For me, like for so many across the world, the last year has felt like an extended, immersive study of “life in survival mode.”

The pandemic has recast basic questions of everyday. Minimizing risk has taken precedence over things like preference or pleasure. Contact-free procurement of groceries. Being compliant with mask-wearing, physical distancing, and frequent sanitization of hands and surfaces. Avoiding crowds; staying “within your bubble.”

Such preoccupations are laudable from the perspective of doing one’s part to help contain a deadly virus. They (hopefully) minimize risk to self and family; they (hopefully) protect others from one’s own germs.

But somewhere along the way, in setting aside preference and pleasure for the greater good, I seem to have set aside purpose, too. Why is it we are all being so careful / trying so hard to stay alive? What is it we are sacrificing so much to preserve? I need reminding…

The plain fact of it is that making “safety” the whole point of living obscures something fundamental: avoiding death is not really living.

“If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me,” Jesus told his disciples. “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit them if they gain the whole world but forfeit their life? Or what will they give in return for their life?” (Matthew 16:24-26).

Jesus is in no way advocating carelessness with one’s health or with the health of one’s neighbor (see the parable of the Good)

Samaritan for details on just how seriously we are supposed to take our neighbor’s health and safety)! But Jesus is insisting that we see the goal – the purpose – the meaning of life as following Him. Any other goal, even gaining the whole world, falls short.

Jesus could have been talking about Covid 19 when he described the intent of the evil one: “The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy.” Consider what the virus has stolen from the world in terms of joy, freedom, productivity, connection – the list goes on. Consider the toll of the killing: several million lives worldwide. And destruction? Who can measure the cost of what has been destroyed in terms of livelihoods and semesters of school and rites of passage, gone forever?

But the contrast between that evil intent and Jesus’s purpose is stark: “I came that they may have life and have it abundantly.” (John 10:10) Instead of stealing, killing, and destroying – Jesus gives abundant life.

Clearly, by “life” Jesus is talking about something more than just continuing to take in oxygen and occupy space on the planet. Jesus points to “life” as his life purpose while remaining clear that “staying alive” is not key to experiencing this life. Paul sums it up nicely: “To live is Christ; to die is gain” Philippians 1:21).

Statements Jesus makes elsewhere in Scripture give us a framework for understanding just how abundant the abundance he offers, is:

• “Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty,” Jesus said to the woman at the well. “The water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life” (John 4:13-14).

• “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life” (John 3:16).

• “I am the way, and the truth, and the life,” Jesus said. “No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6).

The “eternal life” Jesus offers is life that includes abundance in the here and now as well as fellowship with the Father forever after. So life in Christ, according to Jesus, is a both / and proposition – peace and purpose in the world; peace and purpose beyond the world. And that Life has already conquered death – which means to live into it is to be unafraid.

The roof climbers in my neighborhood have blessed me by reminding me – forcefully! – that there is more to life than avoiding death. While I am too old and heavy (and hopefully too wise) to launch myself from the top tier of the gazebo, perhaps I am wise enough to take the lesson to heart. Living into my own life with the unselfconscious abandon and exuberance of the roof climbers, even now, is the only logical response to the life I’ve been offered in Christ.

“Although you have not seen him, you love him; and even though you do not see him now, you believe in him and rejoice with an indescribable and glorious joy, for you are receiving the outcome of your faith, the salvation of your souls” (1 Peter 1:8- 9).

Life abundant = indescribable and glorious joy + salvation. Let’s shout it from the rooftops!

Shannon Vowell writes and teaches about making disciples of Jesus Christ. She blogs at shannonvowell.com.