by Good News | Aug 31, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church. On July 28, 2021, the Board of Trustees of the North Georgia Conference and Mt. Bethel United Methodist Church issued the following joint statement: Mt. Bethel UM Church and the North Georgia Conference of The United Methodist Church have jointly agreed to use their best efforts to resolve an ongoing dispute through a mediation process and will refrain from public comment on this matter until the mediation process has concluded. Mt. Bethel Christian Academy will also be included in the mediation process. Photo courtesy of Mt. Bethel.

By Thomas Lambrecht –

This is a time fraught with anxiety and frustration for many United Methodists. Some progressives are exasperated that they are unable to fully affirm LGBTQ ordination, same-sex marriage, and various gender identities.

Some traditionalists are upset at some of the ways traditionalist pastors and churches appear to have been targeted by unsympathetic bishops. Some on both sides are afraid there will not be a General Conference in 2022 or that the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation will not pass.

This has led a number of local churches to disaffiliate from the denomination. In New England and Texas, it has been primarily liberal congregations exiting. In other parts of the country, traditionalist churches have left. Someone recently counted over 100 congregations that had departed over the past year – both progressive and traditionalist.

Other churches are considering whether or not to use the recently enacted exit path (Para. 2553 adopted at the 2019 General Conference) to leave the denomination. A few have requested to do so, but have been turned down by their bishop or their annual conference. We frequently get calls or emails from pastors or lay leaders asking what is involved in leaving the denomination. Tragically, in a few annual conferences, even asking that question can lead to the annual conference closing the church and dismissing the pastor.

The Cost of Departure. A major obstacle to churches wanting to depart from the denomination is cost. The minimum costs involve payment of two years’ apportionments plus the local church’s pension withdrawal liability.

Let’s take a concrete example of a fairly typical 170-member congregation. Its annual budget is around $290,000, including annual apportionments of $33,000. We have been told that a local church’s pension withdrawal liability can range from 4 – 8 times their annual apportionment. (That figure changes from year to year depending on the performance of the stock market.) That means the pension figure could run from $132,000 to $264,000. Add to that two years’ apportionments of $66,000. That means the cost for this church to leave the denomination now could be anywhere from $198,000 to $330,000. This church could spend from 68 to 115 percent of one year’s budget to leave the denomination now.

Some annual conferences are adding payments to what the General Conference enacted. One conference is requiring churches to pay 30 percent of the assessed value of the property on top of the above listed payments. (This is being challenged before the Judicial Council.) In the example of the congregation above, their property is valued at $8 million. That means an extra $2.4 million, bringing the total to $2.6 to $2.7 million in order to depart.

The numbers for a smaller, 70-member congregation are similar. Their annual budget is $52,800, with apportionments of $7,180. The departure cost for apportionments and pension liabilities could total between $43,080 and $71,800. This congregation could have to pay 81 to 136 percent of its total budget to depart. The property value of $1.5 million could add another 450,000 to that figure. (Please note that apportionment and budget numbers vary in different annual conferences and different congregations. Readers are encouraged to run the numbers for their own local church to get an idea of cost.)

All payments to the annual conference would have to be made prior to the local church’s departure. For most churches, this payout would be impossible. At best, it would strain the church’s financial resources and subtract from money being available for ongoing mission and ministry. Even if the church had no apportionment payments following departure, it would take 6-10 years to break even.

Of course, the compensation for paying all this liability now is that it would release the congregation from any future pension liability. Even if it joins the proposed Global Methodist Church or another Methodist body, it would carry with it no future liability. At the same time, it is uncertain whether any or all of that future liability would ever have to be paid. As long as the stock market does reasonably well, the church (or the new denomination) may never have to pay it.

Under the Protocol, this same congregation would owe zero dollars in order to separate and align with the new Global Methodist Church. They would not have to pay back any loans or grants given them by the annual conference. They would not have to pay any prior unpaid apportionments. Their pension liability would be transferred to the new denomination, so would not have to be paid up front. They would not have to pay a percentage of the property value.

Just from a stewardship perspective, it does not make sense for a congregation to depart from the UM Church now, when waiting a year could save that church tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The Timing of Departure. Another obstacle to the departure of local churches is the timing and how long the process would take. Departure requires a two-thirds vote in favor by a church conference (a meeting of all church members). Para. 2553 calls for the district superintendent to convene a church conference within 120 days of when the superintendent calls for such a conference. That means, the superintendent could delay calling for a conference at the superintendent’s discretion, as long as the conference is scheduled within 120 days of the superintendent’s issuing the call. (This is one of several unfortunate loopholes in Para. 2553.)

More importantly, departure requires a majority vote in favor by the annual conference. A local church could go through all the steps to disaffiliate and then have the annual conference vote no or vote to postpone, as one congregation in Wisconsin just experienced in June.

It is unlikely that an annual conference will convene a special session just to vote on whether one or more local churches can disaffiliate. The next annual conference session would be held in May or June 2022. That is just three months before the scheduled meeting of General Conference at which the Protocol would be considered.

The timing of departure means that a church could spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to disaffiliate only three months before they could make the same decision to separate without charge. Acting to disaffiliate now at most gains a local church three months of an early exit.

By contrast, once the Protocol passes, a district superintendent would have to schedule a church conference within 60 days of the request by the local church. No discretionary delays would be allowed. Further, the annual conference would not need to vote to approve the decision to separate. So actual separation could become effective within 60-90 days (at most) following the adjournment of General Conference.

Vote Required for Separation. Another obstacle may be the two-thirds vote by the church conference required for separation now under Para. 2553. The Protocol allows the church council or equivalent body to decide whether it would take a majority vote or a two-thirds vote to separate under the Protocol. A church that might not reach the two-thirds vote for separation now could wait for the Protocol and separate under a simple majority vote of the church conference.

Reasons to Separate Now. Even given the above disadvantages, some local churches might have a legitimate reason to move into disaffiliation now. They could be in the middle of a crisis, like the Mt. Bethel Church in North Georgia, that forces them to take drastic action now. In some churches, substantial numbers of members might be threatening to leave the church unless it acts now to disaffiliate. Local leaders would have to weigh carefully the urgency of starting the disaffiliation process now, compared with the costs involved.

Another reason to disaffiliate now is if the local church wants to go independent, rather than align with the Global Methodist Church or another new Methodist expression. Churches wanting to be independent could not avail themselves of the terms of the Protocol and would have to follow Para. 2553 anyway, so there would be no point in waiting.

One reason NOT to initiate disaffiliation now is concern that General Conference will not be able to meet in 2022. Some are pessimistic that General Conference will be able to meet due to pandemic travel restrictions. While this is certainly possible, at this point it seems less likely. The Board of Global Ministries and other church leaders are working on ways to ensure that delegates are able to receive their vaccinations, which should enable them to travel to the U.S. and avoid the need for a quarantine. Members of Congress and Senate have been contacted about helping to secure visas for delegates in the event that normal visa processes are not functioning in time. U.S. citizens can now travel to Europe and at least parts of Africa without quarantine. One hopes that vaccinations will increasingly become available in Africa and the Philippines over the next six to nine months, leading to further easing in any travel restrictions.

One needs to be careful about some who are spreading false rumors about whether General Conference can be held as scheduled. One rumor is that the United Methodist General Conference is not even on the Minneapolis Convention Center website, which shows that it probably will not happen. But no events further than six months out are posted on the Convention Center website, so our meeting not being listed means absolutely nothing. Contracts have been signed and preparations for the meeting continue on schedule.

If in the spring of 2022 it becomes apparent that not all overseas delegates would be able to attend General Conference, there would still be time to set up alternatives. Many annual conferences have met virtually. The Wesleyan Covenant Association had a hybrid in-person and virtual meeting. The African Methodist Episcopal Church had a General Conference in two sites. Delegates met simultaneously in South Africa and in the U.S. There are options that would allow General Conference to meet despite some travel restrictions.

Another rumor is that the bishops will not allow the General Conference to meet or will not allow the General Conference to consider the Protocol. United Methodist bishops do not have the power to cancel General Conference. The Commission on the General Conference, of which bishops make up a small minority, makes that decision. United Methodist bishops do not set the agenda of a regular General Conference. The Agenda Committee sets the agenda and the delegates themselves approve it. All petitions legally submitted to the General Conference (including the Protocol) must be voted on at General Conference, according to the Discipline. Bishops cannot prevent General Conference from meeting, nor can they prevent the General Conference from considering the Protocol.

A further worry is, “What if the Protocol does not pass?” At this point, there is still no organized opposition to the Protocol. In fact, several annual conferences (including North Georgia, the largest U.S. conference, and California-Pacific, a very liberal conference) passed resolutions this spring favoring adoption of the Protocol. The Renewal and Reform Coalition (RRC), which includes U.S. evangelical delegates, as well as many delegates from Eastern Europe, the Philippines, and Africa, remains solidly supportive. Many progressives favor the Protocol as the best way for them to pursue their agenda of moving the church to affirm LGBT ordination and same sex marriage. In addition, many centrists are tired of the fighting and just want to resolve the conflict so the church can focus on its mission and ministry. I would not be surprised if the Protocol were to pass by a two-thirds margin at General Conference.

There are bishops who make statements like, “The Protocol will never see the light of day,” and “The Protocol will never pass.” It must be remembered that these same bishops were sure that the One Church Plan would pass the 2019 General Conference in St. Louis. (Of course, it did not.) Some bishops, like most human beings, hear what they want to hear and consider only the “evidence” that agrees with their perspective. So far, the available evidence seems to favor the passing of the Protocol, despite what some bishops think or say.

A Spiritual Perspective. In Matthew 4:1-11, we read how Jesus was tempted by the devil. The interesting thing is that all of the outcomes the devil offered to Jesus – daily provision, protection, even rule over all the kingdoms of the world – were legitimately Jesus’s to claim. God had promised all these outcomes to the Messiah, which is who Jesus was. But the devil was tempting Jesus to claim these legitimate promises in illegitimate ways before the appropriate time had come. The challenge was for Jesus to trust the will of his heavenly Father, instead of making those things happen by himself. And because Jesus had trust in a divine plan, all those promises – provision, protection, and rule – came to Jesus in a supernatural way and with perfect timing.

While there are legitimate and understandable circumstances when local churches may move toward disaffiliation now, we have to be careful we do not preempt God. We can trust God to keep his promises to us, as we remain faithful to him. And his promises to us will come to us in God’s way and in God’s time, as he leads by his Holy Spirit. Sometimes he wants us to be patient while he works things out in his way and time.

The bottom line is that, in the absence of exigent circumstances unique to a particular local church, there may be no compelling reason for local churches to leave the UM Church at this time. In fact, there are strong reasons financially and in terms of timing why waiting for the Protocol may make the best sense. And whether a church exits now through the Para. 2553 process or waits for the Protocol, there is normally no need to hire a law firm to guide the church through the process of separation.

The new Global Methodist Church, when it is formed, will benefit most from all those local churches and annual conferences that desire to align with it to act together and stay together. Working in concert, we can build a new church that is faithful to Scripture and Wesleyan doctrine, as well as effectively structured for ministry in the 21st century. What we wind up with will be worth the wait.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Good News | Aug 30, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Steve Beard –

The sun was bright and unforgiving as I paid my respects at the gravesite of Hank Williams on a bluff in Montgomery, Alabama. A cowboy hat would have helped. The heat was a far cry from the dreary night of January 1, 1953, when much of the South was covered in snow and ice at the time of the country music star’s untimely death in the back seat of his 1952 Cadillac on the way to a concert up north. He was 29 years old.

“Praise the Lord – I Saw the Light” is etched into the massive marble gravestone with rays of light descending from the heavens, splicing right through his legendary name. The column is crowned with musical notes. Below, the base of the monument is adorned by a dozen titles of his boxcar worth of hits such as “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Lovesick Blues,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and “I’ll Never Get Out of this World Alive.” Hank didn’t just tug at your heartstrings, he yanked them. Yanked hard. Dejection, cheating, and loneliness.

He also wrote loads of gospel songs. “I Saw the Light” was his most famous. No one mistook Hank for a saint, but his fans could relate to his message about one glad morning – someday in the future – when the old will be made new and there will be no more tears or toil. Situated above his first name, there is a relatively understated bronze portrait of Hank playing the guitar with his leg propped up on a bar stool. The lyrics echoed through my mind.

I wandered so aimless, life filled with sin

I wouldn’t let my dear savior in

Then Jesus came like a stranger in the night

Praise the Lord, I saw the light.

“I Saw the Light” was a hymn to remind Saturday night backsliders that Sunday morning was right around the bend. The biographies of Williams are gut-punch reading. There was a lifetime of chronic pain from spina bifida, dejection, morphine, and a distillery worth of liquor involved. There’s no need to try to paint the picture prettier than it was. Like so many of us, he was brutally conflicted between the shiny trappings of this world and the salt-of-the-earth gospel truth that he knew in his heart. Hank could have made a country hit out of St. Paul’s declaration: “I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do – this I keep on doing” (Romans 7:18-19).

In downtown Montgomery, there’s a stately statue of Hank only a stone’s throw from the storefront museum that houses his pristine Cadillac convertible. Despite its oversized and audacious curves, the backseat seemed disproportionately cramped for Hank’s lanky 6’2 frame. It was difficult to avoid mournfully staring. The museum was well-stocked with irreplaceable memorabilia, video footage, stylized stage outfits, customized cowboy boots, and photos of the heartbroken throng of all races who filled the streets when he died.

Addressing the 20,000 gathered at the Municipal Auditorium in Montgomery for Hank’s funeral, Dr. Henry L. Lyons told the mourners: “Deep down in the citadel of his inner being, there was desire, burden, fear, ambition, reverse after reverse, bitter disappointment, joy, success, and above all love for people.” He said his songs were about the “things everyone feels. Life itself.” Hank was a crooner for the every man.

Only three blocks away, Chris’ Hot Dogs was Hank’s favorite place to eat lunch. Locals told me that he wrote “Hey Good Lookin’” from one of the stools at the counter. For more than 100 years, Chris’ has been a refuge for people of all walks of life. Despite angry threats from the Ku Klux Klan, both black and white customers were served even during the segregation era. Christopher Anastasios “Mr. Chris” Katechis, a Greek immigrant, opened the diner in 1917. Over the years, he fed other notable customers such as Elvis, Oprah, a handful of U.S. Presidents, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Clark Gable.

Only three blocks away, Chris’ Hot Dogs was Hank’s favorite place to eat lunch. Locals told me that he wrote “Hey Good Lookin’” from one of the stools at the counter. For more than 100 years, Chris’ has been a refuge for people of all walks of life. Despite angry threats from the Ku Klux Klan, both black and white customers were served even during the segregation era. Christopher Anastasios “Mr. Chris” Katechis, a Greek immigrant, opened the diner in 1917. Over the years, he fed other notable customers such as Elvis, Oprah, a handful of U.S. Presidents, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Clark Gable.

It’s a bit like walking into a time warp. “We haven’t changed this place in over 70 years,” Theo, the founder’s son, told me. The stools and booths are “beginning to show their age.” After I ordered my lunch, I looked up in my booth and saw an 8×10 autographed portrait of the late Gov. George Wallace.

Chris’ Hot Dogs in Montgomery, Alabama. Photos by Steve Beard.

Vintage news footage of his infamous 1963 inauguration speech played through my mind. “Idraw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny,” Wallace declared, “and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” As I look up at his face, the image in my vision was superimposed by him defiantly standing on the steps of the University of Alabama to block two Black students from attending.

As I would come to discover, I only knew part of his story.

Long before he became nationally known as a segregationist governor, George Wallace (1919-1998) was simply a struggling lawyer who used to go to Chris’ to buy hot dogs and cigars. In an ironic twist of history, Mr. Chris also served civil rights leaders such as Rosa Parks while she waited for the bus and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. when he was the young pastor in the 1950s of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, a sanctuary in the shadow of the Alabama state capitol.

The portrait of the man peering down at me in my booth was also a perennial candidate for U.S. President. In 1972, there were a dozen Democratic candidates running in the primaries for a race that would eventually pit Richard Nixon against George McGovern. During a campaign stop in Maryland, Wallace was shot five times by an assassin. The attack would leave him permanently paralyzed.

Shortly after his brush with death, convalescing at the Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Wallace received a most unlikely visitor.

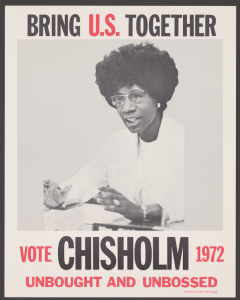

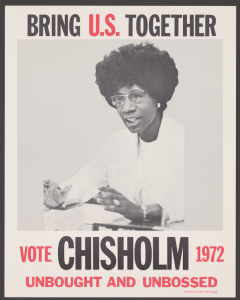

1972 campaign poster for presidential candidate and U.S. Representative Shirley Chisholm. Photo: Library of Congress.

“Shirley Chisholm! What are you doing here?” Wallace asked from his bed. Chisholm was refined, dignified, and decent. She was the first black woman elected to the U.S. Congress and in 1972 became the first African American to run for U.S. President, as well as the first woman to run for the office.

No one was more surprised than Wallace – and her staff – that she suspended her campaign and immediately went to visit her rival. “What will your people say?” Wallace asked. Chisholm responded, “I know what they are going to say. But I wouldn’t want what happened to you to happen to anyone.”

In so many ways, they represented polar opposites fifty years ago. While Wallace was the standard bearer for the Old South and segregation, Chisholm (1924-2005) was a champion of integration, women’s rights, refugees, Native Americans, and the working poor. There were few things they had in common, other than their humanity – and they were both United Methodists. They held hands and prayed together.

Wallace wept.

The medical staff asked her to end their visit because Wallace was very weak. “He held on to my hand so tightly,” Chisholm recalled, “he didn’t want me to go.”

Congresswoman Barbara Lee was a young and idealistic campaign worker for Chisholm in 1972. She was confused and upset about the Wallace visit. In a recent interview with the Washington Post she recollected how Chisholm told her, “Sometimes we have to remember we’re all human beings, and I may be able to teach him something, to help him regain his humanity, to maybe make him open his eyes to make him see something that he has not seen.”

Chisholm also said, “You always have to be optimistic that people can change, and that you can change, and that one act of kindness may make all the difference in the world.”

Chisholm understood that people were angry – very angry – but she believed “you have to rise to the occasion if you’re a leader, and you have to try to break through and you have to try and open and enlighten other people who may hate you.”

In a speech a year after the hospital visit, Chisholm, a member of Janes United Methodist Church in Brooklyn, asked, “Are we ready to learn to deal with others as God has dealt with us? God gave us life at the risk of our rebellion and paid for reconciliation at the price of the cross.”

Back in Montgomery, Wallace arrived at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on a Sunday morning in 1979 unannounced and unexpected. Without fanfare, an attendant rolled his wheelchair to the front of the sanctuary. “I’ve learned what suffering means in a way that was impossible,” he told the African American congregation. “I think I can understand something of the pain that black people have come to endure. I know I contributed to that pain and I can only ask for your forgiveness.” As he left the sanctuary, the congregation sang “Amazing Grace.”

More than twenty years before Wallace found himself before the Dexter Avenue congregation, it was the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. who said in 1957: “Forgiveness does not mean ignoring what has been done or putting a false label on an evil act. It means, rather, that the evil act no longer remains as a barrier to the relationship. … While abhorring segregation, we shall love the segregationist. This is the only way to create the beloved community.”

Shirley Chisholm did not have to approve of George Wallace’s politics in order for her to refuse to allow a barrier or a bullet to stand between them. Her faith would not allow it. A whirlwind of change took place in the man whose portrait I saw in the booth at Chris’ Hot Dogs. The news reel footage and the bitter words would never paint the whole story. Wallace was a four-term governor who sought forgiveness and ended up winning 90 percent of the African American vote during his last campaign.

The Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Steve Beard.

Upon Wallace’s death, civil rights legend John Lewis wrote a moving essay in the New York Times. “With all his failings, Mr. Wallace deserves recognition for seeking redemption for his mistakes,” he wrote, “for his willingness to change and to set things right with those he harmed and with his God.” Perhaps one of the most poignant of illustrations of Wallace’s transformed life was the attendance of Vivian Malone and James Hood, the two black students Wallace tried to bar from the University of Alabama in 1963, at his funeral.

My mind often returns to the bright sunshine on the bluff in Montgomery. A verse from “I Saw the Light” comes into clearer focus.

Just like a blind man, I wandered along

Worries and fears I claimed for my own

Then like the blind man that God gave back his sight

Praise the Lord, I saw the light.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Good News | Aug 30, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

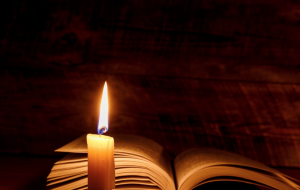

“Jesus himself is called a light in the darkness. He is the light that darkness cannot overcome,” writes Tish Harrison Warren. (Shutterstock).

By Tish Harrison Warren –

It was a dark year in every sense. It began with the move from my sunny hometown, Austin, Texas, to Pittsburgh in early January. One week later, my dad, back in Texas, died in the middle of the night. Always towering and certain as a mountain on the horizon, he was suddenly gone.A month later, I miscarried and hemorrhaged. We made it to the hospital. I was going to be okay, but I needed surgery. They put in a line for a blood transfusion, and told me to lie still. Then, I yelled to Jonathan, lost amidst the nurses, “Compline! I want to pray Compline.” It isn’t normal – even for me – to loudly demand liturgical prayers in a crowded room in the midst of crisis. But in that moment, I needed it, as much as I needed the IV.

Relieved to have a direct command, Jonathan pulled up the Book of Common Prayer on his phone and warned the nurses, “We are both priests, and we’re going to pray now.” And then he launched in: “The Lord grant us a peaceful night and a perfect end.”

Over the metronome beat of my heart monitor, we prayed the entire nighttime prayer service. “Defend us, Lord, from the perils and dangers of this night.” We finished: “The almighty and merciful Lord, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, bless us and keep us. Amen.”

“That’s beautiful,” one of the nurses said. “I’ve never heard that before.”

Bleak season. Grief had compounded. I was homesick. The pain of losing my dad was seismic, still rattling like aftershocks. The next month we found out we were pregnant again. It felt like a miracle. In the end, however, early in my second trimester, we lost another baby, a son.

During that long year, as autumn brought darkening days and frost settled in, I was a priest who couldn’t pray.

I didn’t know how to approach God anymore. There were too many things to say, too many questions without answers. My depth of pain overshadowed my ability with words. And, more painfully, I couldn’t pray because I wasn’t sure how to trust God. Martin Luther wrote about seasons of devastation of faith, when any naïve confidence in the goodness of God withers. It’s then that we meet what Luther calls “the left hand of God.” God becomes foreign to us, perplexing, perhaps even terrifying. Adrift in the current of my own doubt and grief, I was flailing.

If you ask my husband about 2017, he says simply, ”What kept us alive was Compline.” An Anglicization of completorium, or “completion,” Compline is the last prayer office of the day in the Book of Common Prayer. It’s a prayer service designed for nighttime.

Imagine a world without electric light, a world lit dimly by torch or candle, a world full of shadows lurking with unseen terrors, a world in which no one could be summoned when a thief broke in and no ambulance could be called, a world where wild animals hid in the darkness, where demons and ghosts and other creatures of the night were living possibilities for everyone. This is the context in which the Christian practice of nighttime prayers arose, and it shapes the emotional tenor of these prayers.

Nighttime is also a pregnant symbol in the Christian tradition. God made the night. In wisdom, God made things such that every day we face a time of darkness. Yet in Revelation we’re told that at the end of all things, “night will be no more” (Revelation 22:5; cf. Isaiah 60:19). And Jesus himself is called a light in the darkness. He is the light that darkness cannot overcome.

The sixteenth-century Saint John of the Cross coined the phrase “the dark night of the soul” to refer to a time of grief, doubt, and spiritual crisis, when God seems shadowy and distant.

And in a darkness so complete that it’s hard for us to now imagine, Christians rose from their beds and prayed vigils in the night. Long after night vigils ceased to be a regular practice among families, monks continued to pray through the small hours, rising in the middle of the night to sing Psalms together, staving off the threat of darkness. Centuries of Christians have faced their fears of unknown dangers and confessed their own vulnerability each night, using the dependable words the church gave them to pray.

Of course, not all of us feel afraid at night. I have friends who relish nighttime – its stark beauty, its contemplative quiet, its space to think and pray. Yet each of us begins to feel vulnerable if the darkness is too deep or lasts too long. It is in large part due to the presence of light that we can walk around without fear at night. With the flick of a switch, we can see as well as if we were in daylight. But go out into the woods or far from civilization, and we still feel the almost primordial sense of danger and helplessness that nighttime brings.

Compline. I don’t remember when I began praying Compline. It didn’t begin dramatically. I’d heard Compline sung many times in darkened sanctuaries where I’d sneak in late and sit in silence, listening to prayers sung in perfect harmony.

In a home with two priests, copies of the Book of Common Prayer are everywhere, lying around like spare coasters. So one night, lost in the annals of forgotten nights, I picked it up and prayed Compline.

And then I kept doing it. I began praying Compline more often, barely registering it as any kind of new practice. It was just something I did, not every day, but a few nights a week, because I liked it. I found it beautiful and comforting.

For most of my life, I didn’t know there were different kinds of prayer. Prayer meant one thing only: talking to God with words I came up with. Prayer was wordy, unscripted, self-expressive, spontaneous, and original. And I still pray this way, every day. ”Free form” prayer is a good and indispensable way to pray.

But I’ve come to believe that in order to sustain faith over a lifetime, we need to learn different ways of praying. Prayer is a vast territory, with room for silence and shouting, for creativity and repetition, for original and received prayers, for imagination and reason.

I brought a friend to my Anglican church and she objected to how our liturgy contained (in her words) ”other people’s prayers.” She felt that prayer should be an original expression of one’s own thoughts, feelings, and needs. But over a lifetime the ardor of our belief will wax and wane. This is a normal part of the Christian life. Inherited prayers and practices of the church tether us to belief, far more securely than our own vacillating perspective or self-expression.

Prayer forms us. And different ways of prayer aid us just as different types of paint, canvas, color, and light aid a painter.

When I was a priest who could not pray, the prayer offices of the church were the ancient tool God used to teach me to pray again. … When we pray the prayers we’ve been given by the church – the prayers of the psalmist and the saints, the Lord’s Prayer, the Daily Office – we pray beyond what we can know, believe, or drum up in ourselves. ”Other people’s prayers” discipled me; they taught me how to believe again. The sweep of church history exclaims lex orandi, lex credendi, that the law of prayer is the law of belief. We come to God with our little belief, however fleeting and feeble, and in prayer we are taught to walk more deeply into truth.

When I was a priest who could not pray, the prayer offices of the church were the ancient tool God used to teach me to pray again. … When we pray the prayers we’ve been given by the church – the prayers of the psalmist and the saints, the Lord’s Prayer, the Daily Office – we pray beyond what we can know, believe, or drum up in ourselves. ”Other people’s prayers” discipled me; they taught me how to believe again. The sweep of church history exclaims lex orandi, lex credendi, that the law of prayer is the law of belief. We come to God with our little belief, however fleeting and feeble, and in prayer we are taught to walk more deeply into truth.

When my own dark night of the soul came in 2017, nighttime was terrifying. The stillness of night heightened my own sense of loneliness and weakness. Unlit hours brought a vacant space where there was nothing before me but my own fears and whispering doubts.

So I’d fill the long hours of darkness with glowing screens, consuming mass amounts of articles and social media, binge watching Netflix, and guzzling think pieces till I collapsed into a fitful sleep. When I tried to stop, I’d sit instead in the bare night, overwhelmed and afraid. Eventually I’d begin to cry and, feeling miserable, return to screens and distraction – because it was better than sadness. It felt easier, anyway. Less heavy.

I began seeing a counselor. When I told her about my sadness and anxiety at night, she challenged me to turn off digital devices and embrace what she called ”comfort activities” each night – a long bath, a book, a glass of wine, prayer, silence, journaling maybe.

But slowly I started to return to Compline. I needed words to contain my sadness and fear. I needed comfort, but I needed the sort of comfort that doesn’t pretend that things are shiny or safe or right in the world. I needed a comfort that looked unflinchingly at loss and death. And Compline is rung round with death.

It begins ”The Lord Almighty grant us a peaceful night and a perfect end.” A perfect end of what? I’d think – the day, the week? My life? We pray, ”Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit” – the words Jesus spoke as he was dying. We pray, ”Be our light in the darkness, O Lord, and in your great mercy defend us from all perils and dangers of this night,” because we are admitting the thing that, left on my own, I go to great lengths to avoid facing: there are perils and dangers in the night. We end Compline by praying, “That awake we may watch with Christ, and asleep we may rest in peace.” Requiescat in pace. RIP.

Compline speaks to God in the dark. And that’s what I had to learn to do – to pray in the darkness of anxiety and vulnerability, in doubt and disillusionment. It was Compline that gave words to my anxiety and grief and allowed me to reencounter the doctrines of the church not as tidy little antidotes for pain, but as a light in darkness, as good news.

There is one prayer in particular, toward the end of Compline, that came to contain my longing, pain, and hope. It’s a prayer I’ve grown to love, that has come to feel somehow like part of my own body, a prayer we’ve prayed so often now as a family that my eight-year-old can rattle it off verbatim:

“Keep watch, dear Lord, with those who work, or watch, or weep this night, and give your angels charge over those who sleep. Tend the sick, Lord Christ; give rest to the weary, bless the dying, soothe the suffering, pity the afflicted, shield the joyous; and all for your love’s sake. Amen.”

This prayer is widely attributed to St. Augustine, but he almost certainly did not write it. It seems to suddenly appear centuries after Augustine’s death. A gift, silently passed into tradition, that allowed one family at least to endure this glorious, heartbreaking mystery of faith for a little longer.

As I said this prayer each night, I saw faces. I would say ”bless the dying” and imagine the final moments of my father’s life, or my lost sons. I would pray that God would bless those who work and remember the busy nurses who had surrounded me in the hospital. I would say ”shield the joyous” and think of my daughters sleeping safely in their room, cuddled up with their stuffed owl and flamingo. I’d say ”soothe the suffering” and see my mom, newly widowed and adrift in grief on the other side of the country. I’d say ”give rest to the weary” and trace the worry lines on my husband’s sleeping face. And I would think of the collective sorrow of the world, which we all carry in big and small ways – the horrors that take away our breath, and the common, ordinary losses of all our lives.

Like a botanist listing different oak species along a trail, this prayer lists specific categories of human vulnerability. Instead of praying in general for the weak or needy, we pause before particular lived realities, unique instances of mortality and weakness, and invite God into each.

Tish Harrison Warren is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America. She is the author of Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life. This article is adapted from Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep by Tish Harrison Warren. Copyright © 2021 by Tish Harrison Warren. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA. (IVPress.com)

by Good News | Aug 27, 2021 | In the News, Magazine

Photo Courtesy of Alex Grodkiewicz(Unsplash).

By Thomas Lambrecht –

In a sermon preached in the run-up to the 2019 General Conference, Bishop Elaine Stanovsky (Greater Northwest Episcopal Area) promoted the One Church Plan and her vision for the inclusiveness of the church. That vision reflects the understanding of the majority of centrists and progressives in United Methodism. Her sermon is not a systematic treatment of the idea of inclusiveness, but it contains some perspectives and assertions that illustrate the theological gulf existing in United Methodism today. (Thanks to Scott Fritzsche , United Methodist blogger, for pointing out this sermon.)

Handling Scripture

Stanovsky outlines how she believes we ought to read and use the Bible in our theology. “When it comes to the Bible, people make choices about how they listen to what they find there; which stories they let shape and inform their lives, and which they let fade into the background of timebound inscrutability. … People are looking for a biblical story to emerge that deserves to be called ‘good news.’ And when they go searching in the Bible, some passages speak to them, and others they set aside. … The challenge for people like you and me is to find the Good News in the Bible. When we find that, we can let the rest recede into the background.”

There is no question that some passages of Scripture speak more clearly and meaningfully to our current circumstances than other passages do. That is why we can read the Bible today and find something fresh and relevant to our lives that we never saw before, or at least that never spoke to us in the same way before. God’s Word is truly “living and active!”

At the same time, we cannot let our personal, devotional reading of Scripture be the end of our theological engagement with the Bible. Stanovsky notes that the Bible “is so thick and has so many stories, you can find almost any message there.” Reading it only for “what speaks to me” runs the risk of finding in Scripture only what we want to see. Reading it “to find the Good News in the Bible” puts us in the position of determining what “good news” is. We become the arbiters of what the Bible means and teaches, which means we have just created our own personalized religion.

Throughout the history of the Church, it has been recognized that the Bible cannot be simply the property of individuals to make of it what they will. Rather, the Bible is to be interpreted and understood by the Church as a whole, in community. A good example of that is the first Jerusalem Council (Acts 15). The apostles and elders gathered together to discuss and determine what the teaching and moral stance of the church would be, based on Scripture as understood collectively. And the “collective” that interprets Scripture is not limited to just certain Christian scholars and leaders of the church in one nation at one time. Rather, the collective extends back 2,000 years through the history of the church and across the globe.

Stanovsky’s and others’ approach to Scripture makes it easy to “set aside” biblical teachings we do not want to hear or that do not fit our preconceived idea of what the Christian faith is all about. In this case, it enables her to set aside the passages in the Bible that speak about the meaning of marriage and sexuality because they do not agree with her understanding of inclusiveness. She and others can put aside 3,000 years of consistent biblical understanding by both Judaism and the Christian Church in favor of whatever they define as “good news” for today. Our different approaches to Scripture yield a deep difference in theology and moral teaching, particularly in this area of inclusiveness.

All Means All

Stanovsky states, “Some leaders in our Church are asserting that homosexuality is a sin, and that people who choose a life of sin should not be fully accepted in the Church.” She sees the Traditional Plan that was eventually adopted by the 2019 General Conference as “a desperate attempt to define once and for all who is ‘inside’ and who is ‘out.’”

This is a misunderstanding of the traditional position. For traditionalists, it is not a matter of people being accepted in the church or not. Rather, it is a matter of what behavior promotes God-ordained human flourishing and what does not. By performing same-sex marriages, blessing same-sex unions, and ordaining partnered gays and lesbians, the church would be sanctioning relationships that the Bible does not.

Stanovsky goes on, “But in the Bible, in the ‘good news’ section of the Bible, Jesus said, ‘Let the little children come to me, and do not stop them.’ … He invites tax collectors, a woman with a flow of blood, a lame man, a blind man, raving lunatics, lepers, women of questionable reputation, people on their death beds, Samaritans, … a Roman military commander, an Ethiopian Eunuch. … In the gospel of Matthew, Jesus says, ‘Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest’” (emphasis original). In keeping with her approach to the Bible, Stanovsky accepts these “good news” parts of the Bible, while setting aside other parts of the Bible that might contradict or at least temper this message of inclusion.

Stanovsky’s application of these parts of Scripture confuses welcome and invitation with discipleship. Jesus (and by extension the Church) does and ought to welcome and invite all people to come and follow Jesus. The front door of the Church ought to be wide open to everyone.

Once in the door, however, the invitation is to a life of transformative discipleship. The cliché expression is that Jesus accepts us as we are, but he loves us too much to leave us that way.

The provocative illustration of this insight is the parable of the wedding banquet (Matthew 22:1-14). In the story, a king invites many people to a wedding banquet for his son. But the people invited do not show up, despite repeated invitations and pleading. So, the king tells his servants to “go to the street corners and invite to the banquet anyone you find.” They “gathered all the people they could find, the bad as well as the good, and the wedding hall was filled with guests.”

“But when the king came in to see the guests, he noticed a man there who was not wearing wedding clothes. He asked, ‘How did you get in here without wedding clothes, friend?’ The man was speechless. Then the king told the attendants, ‘Tie him hand and foot, and throw him outside into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’ For many are invited, but few are chosen.”

The first group of potential guests refused to come and thereby excluded themselves from God’s reign. The second group, both bad and good, came to the feast as they were, where the king provided them with wedding clothes to wear. But one guest refused to put on the provided wedding clothes. He was unwilling to change. He was good enough as he was, he thought. But he excluded himself from God’s reign by his reliance on his own goodness. “For many are invited, but few [show by their response that they] are chosen.”

The invitation to come to Jesus is all-inclusive. None of us is able to come on our own, apart from the grace of God. We do not rely on our own goodness or merit, but only on the grace and mercy of our crucified and risen Lord.

Entering God’s reign, however, is for those who respond to the invitation in faith and obedience to the way of discipleship. Jesus said, “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven. Many will say to me on that day, “Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name and in your name drive out demons and in your name perform many miracles?’ Then I will tell them plainly, ‘I never knew you. Away from me, you evildoers!’” (Matthew 7:21-23).

I make no judgment here about any individual person’s standing with God. Thankfully, the Lord determines who is “in” and who is “out.” The point is that not everyone will be saved – a tragic reality that ought to spur our motivation to share the faith with everyone in both word and deed. It is the Church’s job to teach and proclaim the faith, realizing that not everyone will respond. To focus in that task on inclusion without fostering obedience to God’s will is to miss a big part of the Gospel. An essential element of faith is striving to do God’s will and live in a way that pleases him.

Of course, it is nearly impossible perfectly and consistently to do the will of our heavenly Father. One of the most popular Methodist sayings is that “we are going on to perfection.” (Translation: we just blew it!) Stanovsky acknowledges this when she says, “In this way, God works in us and through us, to guide us toward loving with a perfect love. To be made perfect in love in this life.” Striving toward perfect love is required of all who would name the name of Christ.

That perfect love is made manifest in obedience to God. As Jesus said, “If you keep my commands, you will remain in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commands and remain in his love” (John 15:10). Or as John puts it, “If anyone obeys [Christ’s] word, love for God is truly made complete in them” (I John 2:5).

The Point of Our Disagreement

We somewhat agree on the goal: everyone is invited, and we ought to strive to be made perfect in love by doing God’s will. The disagreement is not over inclusion – who is “in” and who is “out” – but over what God’s will is. Centrists and progressives believe it is God’s will for same-sex attracted persons to be able to live out and express their sexuality as they feel inclined with persons of the same sex. Traditionalists believe that we ought to all live out our sexuality within the boundaries of monogamous, heterosexual marriage, according to God’s will expressed in the consistent teaching of Scripture.

I could respond further to other aspects of Stanovsky’s sermon. Fritzsche in the post linked up above demonstrates how Stanovsky (and many progressives and centrists) do not take proper account of the doctrine of original sin and its effects on human sexuality.

But I think the core of the disagreement over inclusiveness is confusion between hospitality and discipleship. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, German pastor and theologian during World War II, famously wrote in The Cost of Discipleship, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” The Church’s job is not to be hospitable and make us comfortable with the way we are or to feel content in our sin. Rather, it’s job is to invite us to be crucified with Christ – putting to death the old person with its sinful habits and shortcomings – and be raised to a new life in Christ – by his grace putting on a new self that is clothed in the fruit of the Spirit and living in perfect harmony with God’s intention for a life of human flourishing.

No one ought to be under the illusion that it is easy to be a Christian. We all have our sins and wounds to overcome (hence, the importance in holding to the doctrine of original sin). As another cliché puts it, we are all on level ground at the foot of the cross. None of us can make this discipleship journey by our own strength. We need the supernatural power of God at work in us, and we need the encouragement and accountability of each other in the Body of Christ. It is simply our failure to agree on the standards we are to be accountable to that is leading us to the need to walk separately in different denominations.

by Good News | Aug 26, 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, September/October 2021

“We must go back, way back to our future,” said Bishop Mike Lowry. “We need to go back to the heart of the gospel in its full dimension – both spiritual and social.” Photo by Valerie Johnson (Shutterstock) and modified by Kendall Jablonowski.

By Mike Lowry, Bishop of the Central Texas Conference

The harsh reality is that we are in a post-Christendom age. No longer does the Christian faith, and more specifically the United Methodist Church, assume a leading societal position.

During my first year or so as a bishop, when I would mention that we were in a post-Christian era, clergy would tend to sigh and say, “look we already know this, that’s obvious.” To which I would respond (then and now!) “But I don’t see you changing your behavior. Most of you are operating as if we are still living in a time of Christendom” (i.e. a time of dominant cultural Christianity and influence). When I would make similar observations in a group laity, it almost inevitably sparked passionate discussions about whether this was an accurate or true statement. It would quickly be followed by comments related to the various issues of what we have come to call the “culture wars.”

While there can be no doubt that we are still grappling with various issues of the “culture wars,” I think it is safe today to say that with most of high society, the culture wars are over. In much of American society, traditional cultural Christianity (which is very different from and should not be confused with deep discipled orthodox Christianity!) has largely been defeated. Put bluntly, the cultural wars are largely over, and cultural Christianity lost.

Regardless of where you see yourself and your church on the conservative to liberal (or if you prefer traditional to progressive) spectrum, none of this should be news to us. The challenge of faithfulness is what do we do about this new day and culture in which we find ourselves?

Charles Taylor’s encyclopedic A Secular Age chronicles our movement from a time in history where belief in God was a given that could be assumed to an age where the notion of a transcendent God is one option among many. Closer to earth, in the central part of the State of Texas (the geographical area of the conference I serve), those in regular worship on an average Sunday in the United Methodist Church make up approximately 1.1 percent of the population.

Furthermore, in the eight states of the South Central Jurisdiction of the UM Church, this percentage is roughly average. For a wider view, consider the Washington Post headline: “Church membership in the U.S. has fallen below the majority for the first time in nearly a century.” According to the story, “The proportion of Americans who consider themselves members of a church, synagogue or mosque has dropped below 50 percent … It is the first time that has happened since Gallup first asked the question in 1937, when church membership was 73 percent.”

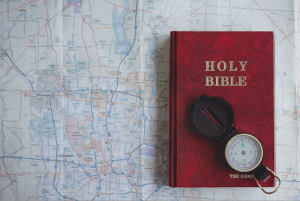

Gil Rendle, the recently retired Senior Consultant for the Texas Methodist Foundation (TMF), has commented about our society that “we are in a moment of seismic shift.” He calls this an anxious time because we need to move ahead without really knowing where we are going. The good folks at TMF talk in terms of “following the North Star of purpose.”

The issue for us is who or what defines and shapes our purpose. For the faithful church of Jesus Christ, the North Star of purpose is driven by the mission of making disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world. For Christians I submit that our purpose should not be driven by our emotions, our preferences, or especially whatever is considered culturally popular (regardless of whether it is progressive or traditional). We will not navigate ourselves out of the morass we are in by the politics of either the left or the right.

“We are, in many ways, a civilization adrift on the stormy seas of relativism and existentialism,” writes Louis Markos in On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis. “The first ‘ism’ has robbed us of any transcendent standard against which we can measure our thoughts, our words, and our deeds; the second has emptied our lives of any higher meaning, purpose, or direction. Our compass is broken and the stars obliterated, and we are left with nothing to navigate by but a vague faith in the modern triad of progress, consumerism, and egalitarianism. They are not enough.”

There is a deep hunger in our times which is at once both counter-intuitive and counter-cultural. Mother Teresa’s comment to a reporter after delivering lectures in America remains strikingly accurate: “I’ve never seen a people so hungry.” Signs of spiritual starvation are all around and yes, even in our churches. We need more than good advice. We need good news! We desperately need the gospel of Jesus Christ!

The truly great news is that this is precisely what God in Christ through the presence and power of the Holy Spirit offers us. We must go back, way back to our future.

Back to Our Future. In the 1989 film Back to the Future II, there is a pivotal scene in which Doc Brown (played by Christopher Lloyd) arrives in his DeLorean time machine to take Marty (Michael J. Fox) and Jennifer (Claudia Wells) back to the future. Reluctant to head off on another adventure through time, Marty asks about the urgency. Doc Brown replies: “It’s your kids, Marty. Something’s got to be done about your kids!”

If not for our sake, then at least for the next generation, let us stop this insidious dance with slow decline in the United Methodist Church. We need to go back to the heart of the gospel in its full dimension – both spiritual and social. Make no mistake. To do so will cut uncomfortably across the scarred wasteland of our cultural wars tearing at every single one of us. It will call us back to our primary allegiance to Christ above and beyond political party, financial gain, racial identity, and even nationality.

The cross is not a symbol of execution, but a sign of victory. The grave is not a grief-filled prison, but an empty tomb of triumph. The birth of the church in worship at Pentecost is not a gathering of polite gentle religion, but an assembly of the troops under the leadership of the Risen Lord through the Spirit’s power and presence, saturated in praise to the glory of God.

We need not fear. We have lived through the crisis of decline and massive cultural change before. Just think of the earliest Christians. They were a tiny, persecuted minority which offered a social witness radically different from any of the competing political or social platforms of their day. They understood themselves to be in, but not of, the world. Thus in 2 Peter, what scholars think might have been a baptismal address, we read: “Thus he has given us, through these things, his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of lust, and may become participants of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4).

A conviction of being in but not of the world was at the very heart of the Methodist movement. In his book John Wesley in America: Restoring Primitive Christianity, Methodist scholar Geordan Hammond concludes that Wesley “continued to believe that primitive Christianity provided a normative model to be restored. Wesley had no doubt that the doctrine, discipline, and practice of the primitive church was embodied by the Methodist movement.”

A crisis is an accelerator. In the slamming impact of COVID-19 and the wrenching internal church doctrinal dispute over human sexuality, we as a church are being given by God an opportunity to re-embrace our purpose and commission. I contend simply that we must go back to the earliest Christian movement in the Roman Empire over the first three centuries and to the early Wesleyan (or Methodist) revival of 18th century England for guidance.

The death of nominal Christianity or cultural Christendom is a good thing. Ironically, or more accurately providentially, the Christian church grows when persecuted and withers when awash in prosperity. Individually and collectively we are being forced, by the movement of the Holy Spirit, to confront whether we are really Christ followers or not. Put theologically and biblically, is Jesus Lord of your life and your church’s collective life or not?

Forward to a New Spring. How then do we move forward in faithfulness and fruitfulness? As stated earlier, the North Star of purpose is driven by the mission of making disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world. It is given to us by the risen Lord for the sake of this disease stricken world. In his book The Forgotten Ways, Alan Hirsch puts it this way: “The desperate, prayer-soaked human clinging to Jesus, the reliance on his Spirit, and the distillation of the gospel message into the simple, uncluttered message of Jesus as Lord and Savior is what catalyzed the missional potencies inherent in the people of God.”

Let me offer three key markers we might employ as elements for moving forward to a new spring from the earliest Christians in the Roman empire: (1) Clear in Christological identity: Jesus is Lord!, (2) Sacrificial in service, and (3) Wise in witness.

The Apostle Paul put it this way in the opening chapter of his letter to the beloved Philippians: “Only, live your life in a manner worthy of the gospel of Christ, so that, whether I come and see you or am absent and hear about you, I will know that you are standing firm in one spirit, striving side by side with one mind for the faith of the gospel, and are in no way intimidated by your opponents. For them this is evidence of their destruction, but of your salvation. And this is God’s doing. For he has graciously granted you the privilege not only of believing in Christ, but of suffering for him as well – since you are having the same struggle that you saw I had and now hear that I still have” (Philippians 1:27-30).

Did you read that? “The privilege” of suffering for Him!

An additional key marker of faithfulness was assumed by the earliest Christians and put firmly in place by the leaders of the Methodist revival. Both embraced the use of small groups for discipleship formation. The first small group was made up of 12 disciples who became the apostles, the sent ones. In the Gospel of Mark we read, “He called the twelve and began to send them out two by two, and gave them authority over the unclean spirits” (Mark 6:7). Those called Methodist under first Wesley and then Asbury’s tutelage in America were required to be a part of a “Class Meeting” for their own spiritual growth and discipleship training.

Moving forward to a new spring necessitates a biblical and theological recovery of the gospel. Both the earliest Christian witness and the Methodist revival focused on what God was doing in and through us, not what we humans are working at. Their focus was on God, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit! I am tired of a spiritually atrophied Unitarian United Methodism which acts as if the Holy Spirit is not real. I have had it with a vague deistic theology which condescends to Jesus as an interesting teacher but denies his kingship. The Lord is calling us back to the center of the Christian faith in the great doctrines of the incarnation, sin, salvation, and sanctification in both their personal and social dimensions. Wesley’s dying breath was anchored on the incarnation: “The best of all is that God is with us.”

Ask yourself, when was the last time you heard (or preached!) a sermon on salvation? When was the last time you were challenged to explicitly turn your life over to Christ – the Lord/leader of your life – over, above, and beyond your own transitory preferences?

Alan Hirsch’s book, Reframation, highlights three aspects of salvation in today’s culture – salvation related to (1) guilt, or (2) shame, or (3) liberation. All three are historically a part of the Christian doctrine of atonement or soteriology (the “way” of salvation). Furthermore, the early Christian Church, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, explicitly refused to limit salvation to simply one element or aspect of life (i.e., sin as related only to guilt), but lifted as the center of orthodoxy the greater understanding of core Christian doctrines like the Trinity, the incarnation, sin, salvation, and the church. It is past time we go back to teaching the essentials of our faith.

Firm core/Flexible strategies. A crucial way to think and pray about our future in a new spring is to guard the core while being flexible in strategy. For years we have done just the opposite. We’ve been loose and even indifferent to the core while being rigid in strategy. The early church, as well as the early Methodists, did just the opposite. They held firmly to the doctrinal core of the Christian faith and were wide open on strategy. Wesley was so flexible on strategy that he went so far as to embrace field preaching, which he considered “vile” (his word, not mine).

For congregations and conferences in the United Methodist Church, guarding the core and being flexible in strategy will involve an openness in organizational structure, creative worship styles, and deployment of clergy (to mention just a few areas) while assiduously rebuilding the doctrinal core of the Church.

A necessity in moving forward in a new spring is the recovery of a working discipline in our life together. This is an uncomfortable subject in today’s rabidly individualistic culture, but I invite us to look back to our future. Indeed, I would go so far as to assert that we must recover a sense of communal discipline, or we shall surely perish.

I have on my desk a “class meeting ticket” which used to be a basic part of being a Methodist. To recover who we truly are – those who are methodical and disciplined in their faith walk – will mean that our church “membership” will be less than our average worship attendance. The earliest Christians held the concept of church discipline so deeply that they debated the issue of readmittance to worship of those who had proved apostate or unfaithful.

Grace must abound, but it cannot be cheap. Currently, I fear that we have strayed into a culture of “cheap grace.” Pouring out his life as a martyr in resistance to Hitler and the Nazis, Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s profound insight should resonate with the core of our being and the practical essence of how we go about being “church” together. “Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession,” he wrote in The Cost of Discipleship. “Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.”

Let all that you do be done in love. Now, I come at last to that element of which I am reluctant to speak. I have come to believe that if we are to find a way forward, as the Holy Spirit is leading us, the United Methodist Church must engage in some form of denominational separation.

In 1786, John Wesley famously said, “I am not afraid that the people called Methodists should ever cease to exist either in Europe or America. But I am afraid lest they should only exist as a dead sect, having the form of religion without the power. And this undoubtedly will be the case unless they hold fast both the doctrine, spirit, and discipline with which they first set out.”

Painfully, this is too often largely the truth in United Methodism today. Our internal church struggle, which I take to be doctrinally important and serious, is damaging the witness of us all. We need to set each other free. It is time we move forward to a new spring through a grace-filled separation which would allow for shared ecumenical ministry and the possibility of a coming back together in the future.

A litigious fight over property and position benefits no one and damages the advancement of the kingdom of God towards which, I trust, we all work and pray. I believe the best way to accomplish this is through the so-called “Protocol” which will be voted upon at General Conference in 2022.

To those of you who insist on some version of unity at all costs, I remind you that we came into being by separating from the Church of England after the Revolutionary War in 1784. I would further ask, based on a historically irrefutable reading of church history, that if you really believe in unity at all costs, then why are you not already a member of either the Greek Orthodox or Roman Catholic branches of the Church universal?

Do you recall the word of the Lord as it comes to us from the Prophet Isaiah? “But now thus says the Lord… Do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name, you are mine… I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert” (Isaiah 43:1, 19).

Do you recall the word of the Lord as it comes to us from the Prophet Isaiah? “But now thus says the Lord… Do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name, you are mine… I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert” (Isaiah 43:1, 19).

Presiding at what I believe will be my last Annual Conference, I think this is where we find ourselves no matter in which camp we place ourselves. We are wandering in the wilderness as a church, and we know what deserts are like. May the words of the Apostle Paul to the contentious, troubled church at Corinth provide guidance to us all: “Keep alert, stand firm in your faith, be courageous, be strong. Let all that you do be done in love” (1 Corinthians 16:13-14).

Mike Lowry is the Bishop of the Central Texas Conference of the United Methodist Church. This is a revised version of an Episcopal address delivered to the conference on June 21, 2021. Upon his retirement, Lowry will join United Theological Seminary as the school’s first Bishop-in-Residence. Bishop Lowry, the longest-tenured leader of the Fort Worth episcopal area, has served the Central Texas Conference since 2008.

by Good News | Aug 11, 2021 | July/August 2021, Magazine, Magazine Articles

By Max Wilkins –

By Max Wilkins –

At TMS Global, we talk a lot about “joining Jesus in his mission.” But what, exactly, is that mission? Maybe you’ve wondered that, too. In recent decades, parts of the church in North America have watered down the mission of Jesus until anyone who is doing anything even remotely helpful or is simply being nice to others is thought to be on mission.

From its inception, however, the actual mission of Jesus has been about one thing: making disciples. Jesus spent the entirety of his earthly ministry making disciples. And as he gathered with his disciples on the evening before he was crucified, he prayed to his heavenly Father: “I have brought you glory on earth by finishing the work you gave me to do” (John 17:4).

It is essential to note that Jesus had not yet been to the cross, much less risen from the dead. He had much remaining work to do. But he had made disciples. And it says something about the importance the Lord places on disciple-making that he would indicate that this was the work his Father sent him to do, and that by doing it, he had brought glory to his Father on earth. How remarkable that Jesus would now entrust this God-glorifying mission to us! Yet, that is exactly what he does.

The final words in Matthew’s gospel have come to be widely known as the Great Commission. It is understood by the church that in these words Jesus is giving marching orders to those who would join him in his mission.

“Then Jesus came to them and said, ‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age’” (Matthew 28:18–20).

There is a command in these verses, and only one. I have had the opportunity to share with communities of believers in dozens of countries around the world, and I commonly ask them: “What is the command in the Great Commission?” Nearly 100 percent of the time the immediate and enthusiastic answer is: “Go!”

Many years ago, the late Christian singer Keith Green recorded a song entitled “Jesus Commands Us to Go.” It is a beautiful song, and the song’s sentiments are shared by many passionate believers. It is, however, also theologically incorrect. The Great Commission does not command us to go. We know this because the text is handed down to us in Greek, a language in which command verbs have their own form. When looking at this passage in Greek, it becomes clear: the only command in the entire passage is “make disciples.” In fact, Jesus seems to assume that those who follow him would not need to be commanded to go. Movement is more or less implied in the act of following. A better translation of this passage in English would be something like: “As you are going … make disciples!”

The mission of Jesus is to make disciples. Period. And while there are thousands and thousands of ways to make disciples, and we can utilize many platforms to accomplish this vital work, not everything that is nice and helpful is also disciple-making. It is essential that those who would live lives worthy of the calling of Jesus be about the work of making disciples. It is the only mission that ultimately matters, and the one that brings glory to God on the earth.

The good news is that we are not on our own as we live into this mission. Paul reminds the believers in Thessalonica that it is the power of God that makes the mission possible. These outcomes are both accomplished “by his power” (2 Thessalonians 1:11).

At TMS Global our mission statement calls us to join Jesus in his mission, but we understand that mission to be making disciples. Thus, all TMS Global cross-cultural workers are engaged in disciple-making regardless of their platform for ministry.

Max Wilkins is the president and CEO of TMS Global. This column is adapted from his latest book, Focusing My Gaze: Beholding the Upward, Inward, Outward Mission of Jesus. To learn more, visit seedbed.com/focusingmygaze, or inside cover.