by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

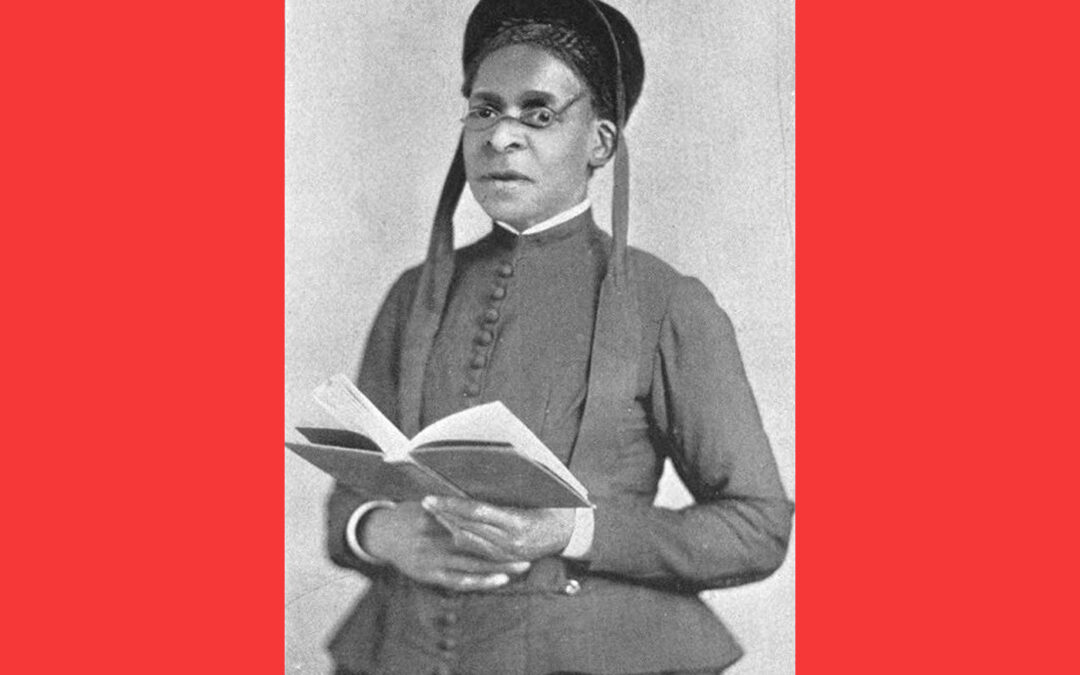

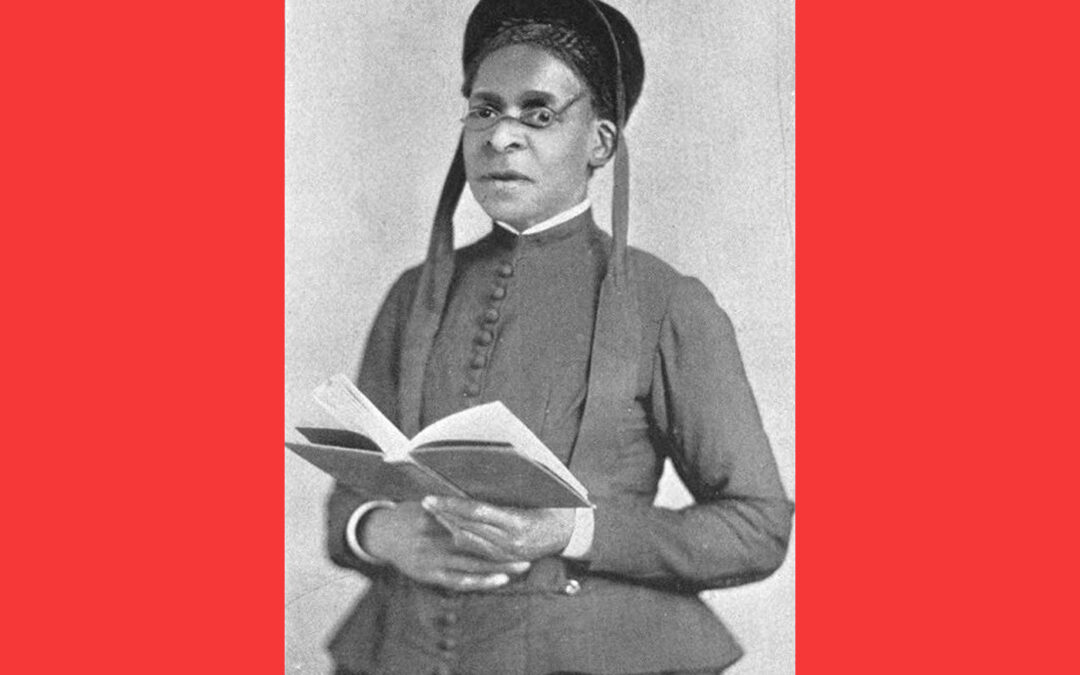

Julia Foote and the Geography of Witness

By Elizabeth Glass Turner – 2021 –

What do you know of Zanesville, Ohio? History buffs might enjoy its distinct Y-shaped bridge or explore its history as part of the Underground Railroad or recall it for its well-known river and locks. If a spiritual pilgrimage were traced across the tilts and rolls of Ohio’s farms, rivers, and valleys, Methodists might mark a gentle circle around Zanesville. It’s not unique for towns that sprang up across the Midwest to have Methodist fellowships woven through their roots; but those Methodist fellowships in the mid-1800s were not without profound flaws.

In the autobiography of Julia Foote – happily available for download through Asbury Theological Seminary’s First Fruits Press – readers are confronted with this reality. On joining the local Methodist Episcopal church (in the state of New York), her parents, both former slaves, were relegated to seating in one part of the balcony of the local church and could not partake of Holy Communion until the white church members, including the lower class ones, had gone first.

Eventually, Julia Foote would become the first woman ordained a deacon in the AME Zion church, the second woman ordained an elder. Before that, she was an evangelist, traveling and preaching in a number of places, starting before the Civil War. At times, congregational conflict emerged when she visited a town, sometimes because Foote was Black, sometimes because she was a woman. But the testimony of her visit to Zanesville is different.

Before arriving in Zanesville in the early 1850’s, Foote had been in Cincinnati and Columbus, then visited a town called Chillicothe. Her time in Chillicothe was fruitful but not without controversy.

The following excerpts retain Foote’s own original language, a reflection of the time in which she lived:

“In April, 1851, we visited Chillicothe, and had some glorious meetings there. Great crowds attended every night, and the altar was crowded with anxious inquirers. Some of the deacons of the white people’s Baptist church invited me to preach in their church, but I declined to do so, on account of the opposition of the pastor, who was very much set against women’s preaching,” she wrote. “He said so much against it, and against the members who wished me to preach, that they called a church meeting, and I heard that they finally dismissed him. The white Methodists invited me to speak for them, but did not want the colored people to attend the meeting. I would not agree to any such arrangement, and, therefore, I did not speak for them. Prejudice had closed the door of their sanctuary against the colored people of the place, virtually saying: ‘The Gospel shall not be free to all.’ Our benign Master and Saviour said: ‘Go, preach my Gospel to all’” (Julia A. J. Foote, A Brand Plucked from the Fire: An Autobiographical Sketch, First Fruits Press).

Whether or not the good Baptists of Chillicothe today know that their forebears ousted a pastor who objected to a woman evangelist, the Methodists may be unaware that their forebears invited a Black woman to preach – but only if people of color were excluded from the meeting. And yet, in spite of these local controversies, Julia Foote wrote that in that town, “we had some glorious meetings,” and “the altar was crowded.” Like John Wesley, Foote sowed grace outside church buildings, even if she could not sow grace inside church buildings. Like the Apostle Paul, she proclaimed the Gospel to those who would welcome her.

But then, she went to Zanesville. And here, readers see a different move of the Holy Spirit. What was the difference?

“We visited Zanesville, Ohio, laboring for white and colored people. The white Methodists opened their house for the admission of colored people for the first time. Hundreds were turned away at each meeting, unable to get in; and, although the house was so crowded, perfect order prevailed,” Foote wrote in A Brand Plucked. “We also held meetings on the other side of the river. God the Holy Ghost was powerfully manifest in all these meetings. I was the recipient of many mercies, and passed through various exercises. In all of them I could trace the hand of God and claim divine assistance whenever I most needed it. Whatever I needed, by faith I had. Glory! glory!! While God lives, and Jesus sits on his right hand, nothing shall be impossible unto me, if I hold fast faith with a pure conscience.”

Foote labored for any and all for the sake of the Kingdom when she arrived in Zanesville. While there, for the first time, Methodist worship was integrated. So many people came, hundreds had to be turned away. Despite the crowds, there was no controversy or dispute. And – “God the Holy Ghost was powerfully manifest in all these meetings.” There was no segregated worship; the Holy Ghost was powerfully manifest.

This is powerful testimony reverberating down through the soil, through the generations, through the Kingdom. Sitting today in a different part of the state over 150 years later, I read the words of Julia Foote and see the rolling hills of Ohio differently. I’ve been in Cincinnati, and Columbus, and Chillicothe. I’ve read those names on road signs. I’ve seen church buildings in those places. Through her words, I hear the voice of a mother of American Methodism, particularly the holiness movement, calling across the rivers, the years. She was pressed, but not crushed; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. Her eyes too saw this rural landscape in the springtime; heading from Zanesville on to Detroit, she also likely saw Mennonite and Amish farmers along the road. She sowed grace into this landscape before my great-grandmother was born. Before the Wright brothers followed the birds skimming along air currents, Julia Foote learned how to glide on the wind of the Spirit: “whatever I needed, by faith I had.”

Today, in the yard outside my window, irises are blooming that I did not plant; someone else planted, another watered, and I enjoy the deep purple unfurling from the bud. Reading of Foote’s ministry, I am given a window onto the grace planted by faith, the results of which would have shaped the spiritual life of a community for decades. But it does not let me rest on what came before; her labor calls out across the rivers, the years, questioning: how are you tending to what others planted through the Spirit? She endured great hardship to proclaim the Word of God in this landscape. I would not rip out or mow over the irises carefully planted by another; how might I help to care for what she was bold enough to sow? Decades later – and yet not so very long at all – where is the Spirit brooding, full, like a thundercloud full with rain, ready to burst?

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

The gifts you have, for the good of others.

It is the Holy Spirit who transforms history into testimony, the same Spirit who was “powerfully manifest” now bearing down, laboring again. In the original introduction to A Brand Plucked, Thomas K. Doty wrote, “Those of us who heard her preach, last year, at Lodi, where she held the almost breathless attention of five thousand people, by the eloquence of the Holy Ghost, know well where is the hiding of her power.”

What do you know of Zanesville, Ohio? That Julia Foote preached there in the 1850s, sowing grace? That Methodists there rejected segregated worship, joining together, and the Holy Spirit was “powerfully manifest”?

What do you know of the Holy Spirit, today? What do you know of those who planted and watered while God gave the increase, long before you saw the buds?

Sisters and brothers, we do not walk into ministry alone today. Wherever you are, someone has gone ahead, sowing grace ahead of you. If the rivers could speak, they might gossip to you about the ones who went before; who crossed rivers when no plane had yet crossed the sky.

What do you know of Zanesville, Holy Spirit? Hearts there once were soft.

What do you know of the Holy Spirit, Zanesville? Once, the Spirit was powerfully manifest in your midst.

Holy Spirit, where are you brooding now? Give us the grace of readiness..

Elizabeth Glass Turner, a frequent contributor to Good News, is the editor of Wesleyan Accent (www.WesleyanAccent.com). This article is reprinted by permission of Wesleyan Accent.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“The Sabbath is different from the other six days, because it is the day we stop using our time to gain something for ourselves and return to the fact that our time belongs to God,” writes the Rev. Nako Kellum. Photo by Tyler Lastovich (Pexels).

By Nako Kellum –

Shortly after I bought my first smart phone, I was at Disney World with my family for vacation. When I was standing in line for “It’s a Small World,” I received a text from work, and without thinking, I answered it immediately. Then, a thought came to me, “If I did not have this phone, I could not have been reached, and I would not have responded during my vacation!” That day, I felt like I lost something significant.

With the advance of technology, it is difficult to keep the Sabbath. Instead of going to work and sitting in front of computer, we carry “work” with us, 24/7.

I have to confess that for a long time, I have had “days off,” but I have not practiced Sabbath keeping. According to Eugene Peterson, these two are different things. He calls a day off “a bastard sabbath.” Usually, my days off are filled with different “have-to” errands – grocery shopping, cooking, doing laundry, cleaning, the children’s extra-curricular activities, etc. It was not until recently that I learned about what observing the biblical Sabbath truly means, and how much I need it.

Of course, I knew Sabbath-keeping is one of the Ten Commandments, but I do not think I took it as seriously as the other Commandments. I was careful about not having any other gods or making an idol and even preached about it. I was careful to not use the name of the LORD in vain. I honored my parents, and I took the commandments against murder, adultery, stealing, and coveting seriously. But Sabbath keeping? Not so much. Yet, in the Ten Commandments, it is the only commandment that comes with the reason as to why we have to keep it. “Remember to observe the Sabbath day by keeping it holy … For in six days, the LORD made the heavens, the earth, the sea, and everything in them; but on the seventh day he rested. That is why the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and set it apart as holy” (Exodus 20:8,11, emphasis added).

God established the rhythm of our lives in creation – work for six days and stop on the seventh day. It is based on God’s action in creation, and as his image-bearers, we are to follow him. If we play by our own rhythm instead of God’s, we disrupt the harmony God built into his creation. Maybe that is why we have problems such as stress or burn-out; we are out of sync with his rhythm.

The Sabbath is not just a simple day that we quit working; it is a day of “rest dedicated to the LORD your God” (Exodus 20:10). It is a day we reorient our perspectives on our lives. Sabbath in Hebrew means to “cease” or to “stop.” The Sabbath is different from the other six days, because it is the day we stop using our time to gain something for ourselves and return to the fact that our time belongs to God. It is the day we remind ourselves that we are not God; it is God who runs this universe. It is interesting that in Jewish culture, the Sabbath begins at sundown on Friday and ends at sundown on Saturday. All we must do at sundown is eat and go to bed; the only one who is awake is God. When we wake up, God is already at work. It reminds me that God is the one who takes the initiative, and he is the one who is sustaining the world. My part is to see what he is already doing and participate in his work. It is a day to pay close attention to God, and what he does in this world.

Another aspect of the Sabbath is that it is a day to remind us of who we are – human “beings,” not human “doings.” In Deuteronomy 5:15, after giving the commandment on the Sabbath, Moses says, “Remember that you were once slaves in Egypt, but the LORD your God brought you out with his strong hand and powerful arm. That is why the LORD your God has commanded you to rest on the Sabbath day.” The Israelites came out of slavery, during which time they were treated harshly and had to work seven days a week. They probably felt relief that they had a day that they did not have to work. When we value human beings, including ourselves, in terms of productivity, we lose a bit of our humanity, as God created us to be. He did not create us to be machines, but he created us as “beings” who enjoy being with him and with people. The Sabbath lets us just “be” in his presence and with each other, without worrying about being productive or accomplishing something. This may be one of the most counter-cultural things we can do as Christians now, in a culture where people are valued in terms of how much money they make, or their status, or which school they attended.

God blessed the seventh day of Creation, and he blesses the Sabbath day. Psalm 92 is a song of the Sabbath Day, which starts with giving thanks and praise to God. The Sabbath is a day of celebration and worship, as we give thanks and praise to God for who he is and his work. It is a day to enjoy God’s creation, delighting in the good gifts he has given us, and simply having fun.

To be honest, observing the Sabbath has not been easy. It is difficult for me to keep a full day of Sabbath (which I try to do on Saturday), but let me share a few things I have learned so far:

• Observing the Sabbath is a spiritual discipline. It does not just happen automatically. It takes intentionality just like any other spiritual discipline.

• It takes preparation. If I want to take a break from doing chores, I need to finish them by my Sabbath. It means no more procrastination regarding my work, which means I have to prioritize what I do during the six days.

• I must be careful not to be legalistic about it either. Jesus said, “The Sabbath was made to meet the needs of people, and not people to meet the requirements of the Sabbath.” I have to keep in mind the heart of God behind the Sabbath and see it as a gift and grace from God. There are days I cannot keep 24 hours of Sabbath, and that is okay for now.

• The church runs fine without me, and our family is fine even if the house is not tidy and we eat frozen pizza on paper plates. In other words, I have learned the world runs just fine without me running around, trying to do all my “have-to” errands. It takes away a sense of self-importance and control and it reminds me that God is the one who initiates the work and He’s always at work.

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

If you do not keep the Sabbath, I invite you to join me in this journey of Sabbath-keeping. Let us not check texts or emails for a day. Let us just “be” with God and with each other. Let us go outside and put ourselves in his creation that he has called “good.” Let us rest, have fun, and enjoy the good and beautiful gifts God gives us and be thankful.

Nako Kellum is co-pastor in charge at Tarpon Springs First United Methodist Church in Tarpon Springs, Florida. The Rev. Kellum is also a member of the Wesleyan Covenant Association Global Council. This article originally appeared on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website and is reprinted here by permission.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

On September 4, 1771, Francis Asbury left England in order to preach the gospel in America. During his lengthy journey, Asbury asked himself, “Whither am I going? To the New World. What to do? … I am going to live to God, and to bring others so to do.” We celebrate this 250th anniversary of his crossing the Atlantic to share the gospel of Christ. Francis Asbury statue at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. Good News file photo.

By John Wigger –

Francis Asbury lived one of the most remarkable lives in American history, a life that many have admired but few have envied. The son of an English gardener, he became one of America’s leading religious voices and the person most responsible for shaping American Methodism.

During his 45-year career in America (he died in 1816), he never married or owned much more than he could carry on horseback. He led a wanderer’s life of voluntary poverty and intense introspection.

The church and the nation ultimately disappointed him, but his faith never did. Asbury embodies Methodism’s greatest successes and its most wrenching failures.

Asbury traveled at least 130,000 miles by horse and crossed the Allegheny Mountains some sixty times. For many years he visited nearly every state once a year, and traveled more extensively across the American landscape than probably any other American of his day. He preached more than ten thousand sermons and probably ordained from two thousand to three thousand preachers. He was more widely recognized face to face than any person of his generation, including such national figures as Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Landlords and tavern keepers knew him on sight in every region, and parents named more than a thousand children after him. People called out his name as he passed by on the road.

Like any good eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century evangelical, Asbury was never satisfied with his own piety or labors. Yet people saw in him an example of single-minded dedication to the gospel that they themselves had never managed to attain, but to which, on their better days, they aspired. In their eyes he was indeed a saint. Though he spent his life traveling, he insisted on riding inexpensive horses and using cheap saddles and riding gear. He ate sparingly and usually got up at 4 or 5 a.m. to pray for an hour in the stillness before dawn. No one believed that Asbury was perfect, and even his most ardent supporters admitted that he made mistakes in running the church. Yet his piety and underlying motivations seemed genuine to almost everyone.

His legacy is not in books and sermons, but in the thousands of preachers whose careers he shaped one conversation at a time, and in the tens of thousands of ordinary believers who saw him up close and took him (in however limited a way) as their guide. Asbury communicated his vision for Methodism in four enduring ways.

1. Asbury had legendary piety and perseverance, rooted in a classically evangelical conversion experience. Piety isn’t a word we use much anymore. It simply refers to devotion to God and serving others, to a desire to “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind,” and “thy neighbour as thyself.”

Where most Methodists, even most preachers, settled for a serviceable faith, Asbury strove for a life of extraordinary devotion. During his forty-five years in America he essentially lived as a houseguest in thousands of other people’s homes across the land. He lived one of the most transparent lives imaginable, with no private life beyond the confines of his mind. Asbury’s piety brought him respect, even renown, based on sacrifice rather than accumulation of buildings, money, or other trappings of power.

2. Asbury communicated his vision through his ability to connect with ordinary people. As he crisscrossed the nation from year to year, he conversed with countless thousands, demonstrating a gift for building relationships face to face or in small groups. It is remarkable how many of those he met became permanent friends, even after a single conversation. They loved to have him in their homes. Asbury often chided himself for talking too much and too freely, especially late at night. He considered this love of close, often lighthearted, conversation a drain on his piety. In reality it was one of his greatest strengths, allowing him to build deep and lasting relationships and to feel closely the pulse of the church and the nation.

Henry Boehm, who traveled some 25,000 miles with Asbury from 1808 to 1813, recalled that “in private circles he would unbend, and relate amusing incidents and laugh most heartily.” He could also be funny, which enhanced his appeal.

3. Asbury understood and used popular culture. Asbury was remarkably well-informed (the product of his travels and love of conversation) and flexible in keeping up with these changes, but everyone has their limits. Though the American Revolution led to a good deal of persecution of American Methodists, Asbury fretted that its end would produce too much prosperity and thereby dampen Methodist zeal. As long as they were poor, most Methodists agreed with Asbury that wealth was a snare. But as Methodists became generally more prosperous, they became less concerned about the dangers of wealth, much to Asbury’s dismay.

4. Asbury communicated his message through his organization of the Methodist church. He was a brilliant administrator and a keen judge of human motivations. As Asbury crisscrossed the nation year in and year out, he attended to countless administrative details. Yet he never lost sight of the people involved. “I have always taken a pleasure as far as it was in my power, to bring men of merit & standing forward,” he wrote to the preacher Daniel Hitt in 1801.

The system Asbury crafted made it possible to keep tabs on thousands of preachers and lay workers. No merchant of the early nineteenth century could match Asbury’s nationwide network of class leaders, circuit stewards, book stewards, exhorters, local preachers, circuit riders, and presiding elders, or the movement’s system of class meetings, circuit preaching, quarterly meetings, annual conferences, and quadrennial general conferences, all churning out detailed statistical reports to be consolidated and published on a regular basis.

Under Asbury, the typical American itinerant rode a predominantly rural circuit 200 to 500 miles in circumference, typically with twenty-five to thirty preaching appointments per round. He completed the circuit every two to six weeks, with the standard being a four weeks’ circuit of 400 miles. This meant that circuit riders had to travel and preach nearly every day, with only a few days for rest each month.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

The Methodist church grew at an unprecedented rate, rising from a few hundred members in 1771, the year he came to America, to more than two hundred thousand in 1816, the year of his death. Methodism was the largest and most dynamic popular religious movement in America between the Revolution and the Civil War. In 1775, fewer than one out of every eight hundred Americans was a Methodist; by 1812, Methodists numbered one out of every thirty-six Americans.

He believed that true religion embraced the suffering of the poor and did all that was possible to alleviate it. This is why he allowed himself few comforts. He once told Boehm “that the equipment of a Methodist minister consisted of a horse, saddle and bridle, one suit of clothes, a watch, a pocket Bible, and a hymn book. Anything else would be an encumbrance.” Indeed, Asbury rarely owned much more than this. At the same time, he gave away nearly all the money that came his way.

“His charity knew no bounds but the limits of its resources; nor did I ever know him let an object of charity pass without contributing something for their relief,” John Wesley Bond wrote. He recalled that Asbury often gave money to strangers he met on the road whose circumstances seemed dire, especially widows. He had his share of failings, but the love of money wasn’t one of them.

Much of what makes human life so interesting – family, romance, creating an intellectual legacy – were largely absent from Asbury’s life after his arrival in America as a missionary. But Asbury’s life wasn’t flat, revolving as it did around the relationships he formed with other Methodists. Asbury lived his life in public, and the community of Methodist believers spread across the country became his vast extended family. He must be understood in this context or not at all. Like a rock thrown into a pond, his life sent ripples through the Methodist movement to its most distant reaches.

Asbury wasn’t an intellectual, charismatic performer, or autocrat, but his understanding of what it meant to be pious, connected, culturally aware, and effectively organized redefined religious leadership in America.

John Wigger is Professor of History at the University of Missouri. He is the author of PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America and co-editor, with Nathan Hatch, of Methodism and the Shaping of American Culture. Reprinted with permission from American Saint: Francis Asbury & The Methodists by John Wigger, published by Oxford University Press, Inc. © 2009 Oxford University Press.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“I am convinced that tithing to a missional organization and then serving that organization is the most strategic thing you can do to change the world,” writes Dr. Carolyn Moore. Photo: Shutterstock.

By Carolyn Moore –

Jesus understood the deep and rich connection between our stuff and our souls. He knew that giving is not a financial issue, but a spiritual issue. We know this, because the Bible is full of this kind of talk. It contains more than 700 references to our use of money. Two-thirds of Jesus’ parables talk about materialism and money. Jesus talked more about money than he did heaven and hell and prayer combined. I’d say that Jesus thinks how you use your money matters.

That’s why I love talking about money in church. I get the connection between our faith and our stuff, and I know it can be a real barrier for some of us in growing toward Jesus. So I love talking about it as a discipleship issue and as a spiritual discipline; and I have a genuine desire to see Jesus holy-fy every nook and cranny of our life.

I am convinced that tithing to a missional organization and then serving that organization is the most strategic thing you can do to change the world, and this pandemic has only strengthened that conviction. I believe this with my whole being: As a faithful giver and also as a concerned voter, I believe my vote is not the most powerful tool at my disposal. My active connection to my local missional community is my most powerful tool against the darkness in this world. Because remember: the mission of Jesus begins in relationship. Giving is not first of all about mission or efficiency or even evangelism. Giving is rooted in relationship – being with, not doing for. This is the gist of Acts 4:32, which I believe best sums up how a life steeped in grace is lived out: “All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had” (Acts 4:32).

This is the attitude of people who have been transformed through the power of the Holy Spirit. We become the New Covenant temple (or as Tim Mackie puts it, “The temple becomes us.”). We see ourselves and our stuff not as ours at all but as part of a whole. Our character becomes that of a confident giver, because we have received the spirit of God who is at his core a Giver. God is a giver who gives to us, and when his Spirit fills us his character becomes our character. And that self-giving connects us back to God.

This Acts 4:32 life is so in rhythm with God’s ways, so in sync with his purposes, that the journey is no longer a fight against a self-protective spirit but a knee-bowing, Spirit-bearing, hungry cry for boldness to speak the Word and become an extension of God’s healing, sign-producing, and wonder-inspiring hand.

N.T. Wright puts it this way: “What you do with your money and possessions declares loudly what sort of a community you are, and the early church’s practice was clear and definite.” Their practice was Acts 4:32.

And it really does work! Ron Sider has done the math and he says, “If American Christians simply gave a tithe rather than the current one-quarter of a tithe (which is our average), there would be enough private Christian dollars to provide basic health care and education to all the poor of the earth. And we would still have an extra $60-70 billion left over for evangelism around the world.”

In the words of Acts 4:32, we discover the audacious claim of generosity: Out of giving comes great power.

Friends, grace is power. When it comes to giving, more information won’t give you more power. More time, more resources, more control, more … you name it … none of it will give you more power. When it comes to giving, grace is power.

This is exactly how it worked with the apostles.

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

Out of giving comes great power.

There is such a deep and rich connection between our stuff and our souls. That’s why money really is a significant discipleship issue. It is because Jesus has a deep desire to holy-fy every nook and cranny of your life, especially the parts you’d rather protect. And that is because Jesus wants your heart … all of it.

Carolyn Moore is the founding and lead pastor of Mosaic Church in Evans, Georgia. She is the chair of the Wesleyan Covenant Association Council. Dr. Moore is the author of many books including Supernatural: Experiencing the Power of God’s Kingdom. Dr. Moore blogs at artofholiness.com. Reprinted from her blog by permission.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Delegates to the 2019 Legislative Assembly of the Wesleyan Covenant Association deliberate on proposals presented to the body. Photo courtesy of the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

By Thomas Lambrecht –

What will the proposed new Global Methodist Church look like? How will it operate? In what ways will it be different from what we have been accustomed to in The United Methodist Church?

These questions weigh on the minds of people who are thinking about the option of aligning with the GM Church after the UM Church’s 2022 General Conference adopts the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation.

Change is difficult. We tend to prefer sticking with what we are used to. Of course, the whole reason for forming the GM Church is because we believe there are some crucial changes needed in how the UM Church currently operates.

Forming a new denomination essentially from scratch is a difficult and complex undertaking. Most United Methodists have never read the Book of Discipline, and they trust their pastor, district superintendent, and bishop to know how the church is supposed to run. Therefore, comparing provisions in the UM Church’s 800-page Book of Discipline with the GM Church’s much shorter Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline would be a tedious task for most United Methodists.

That is why we have undertaken to produce a comprehensive comparison chart (it has been posted on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website as a pdf – wesleyancovenant.org). It summarizes the main provisions of the UM Book of Discipline, the Global Methodist Church’s Transitional Doctrines and Discipline, and the proposals from the Wesleyan Covenant Association’s draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline. The chart shows how most of the important provisions of church governance are handled in the UM Church compared with how they would be handled in the GM Church.

It is important to keep the three documents clear in our understanding. The Book of Discipline governs how United Methodist conferences and congregations function today. It was adopted by the 2016 General Conference (with a few revisions in 2019) and is the result of an evolutionary process extending back to the very first Discipline in 1808. We do not know what the UM Church’s Book of Discipline will look like after the realignment contemplated by the Protocol is accomplished, but we know that significant changes to the church’s moral teachings have been proposed.

The Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline will govern how the GM Church functions from its inception until its convening General Conference meets (an approximately one- to two-year period). It borrows some features from the UM Discipline and some ideas from the WCA’s draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline. It was drafted by a three-person writing team and then amended and approved by the Transitional Leadership Council, which is the governing body for the GM Church from now through the transition until the convening General Conference.

The Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline fleshes out in greater detail than the WCA draft book some of the critical elements necessary to have the denomination running. It elaborates transitional provisions that would help individuals, clergy, congregations, and conferences move into the GM Church. However, anything that was not necessary for the transitional period – such as the manner of selecting and appointing bishops – has been left for the convening General Conference to decide.

In order to minimize the amount of change that congregations would experience during the transitional period, the Transitional Leadership Council sought to maintain continuity with the current UM Discipline where it made sense – such as in the appointment process for clergy to churches (although enhanced consultation with congregations will be required). At the same time, some critically important reforms – such as shortening the timeline for candidacy to ordained ministry – were incorporated in the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline as essential elements of the new church and features that would set the direction of the denomination.

Four of the issues on the Comparison Chart regarding Methodism’s future found on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website.

Ultimately, the GM Church’s convening General Conference, composed of delegates elected globally from among those who align with the new church, will have the authority to formally adopt a new, more permanent Book of Doctrines and Discipline. It will undoubtedly build as a starting point upon the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline. The WCA’s recommendations and other ideas laity and clergy wish to propose will be considered and potentially adopted by the General Conference. Notably, WCA recommendations not in the transitional book would not take effect unless adopted by the convening General Conference. However, they are an important indicator of the current thinking of denominational leaders.

The comparison chart is meant to be an easy way to compare how the GM Church will function during the transition and give an indication of some of the directions envisioned for its future. The chart may be reproduced and shared freely. Questions and feedback are welcome and can be sent to info @ globalmethodist.org.

Some highlights from the chart, specifically referring to the GM Church’s transitional period:

• Doctrine – The doctrinal standards will stay the same, with the addition of the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds, and bishops and clergy will be expected to promote and defend the doctrines of the church.

• Social Issues – The Transitional church will be governed by a two-page statement of basic social witness in the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline, compared with over 930 pages in the UM Discipline and Book of Resolutions. That statement would be binding on clergy and congregations. No changes or additions to this statement will take place before the inaugural General Conference of the new denomination. That General Conference will determine whether and how to write an expanded statement of social principles.

• Local Church Membership Categories – Similar to the UM Church.

• Local Church Organizational Structure – Flexible structures allowed to accomplish the necessary administrative tasks.

• Connectional Funding (Apportionments) – 1.5 percent of local church income for general church work, 5-10 percent for annual conference, including the bishop’s salary and expenses.

• Trust Clause – Local church owns its property (no trust clause). Local churches with pension liability would remain liable if the church disaffiliates.

• Local Church Disaffiliation – Would allow for involuntary disaffiliation if necessary for churches teaching doctrines or engaging in practices contrary to the GM Book of Doctrines and Discipline. Voluntary disaffiliation possible by majority vote of the congregation. No payments required, except pension liabilities where applicable, secured by a lien on the property.

• Certified Laity in Ministry – Combines all types into one category called certified lay ministers, who can specialize to serve in any of the previous areas (e.g., lay speakers, lay servants, deaconesses, etc.).

• Orders of Ministry – Order of deacon contains both permanent deacons and those going on to elder’s orders.

• Length of Candidacy for Ordained Ministry – Six months to three years.

• Educational Requirements for Deacons – Five or six prescribed courses before ordination and four or five courses thereafter.

• Educational Requirements for Elders – Six prescribed courses before ordination and four courses thereafter.

• Licensed Local Pastors (non-ordained) – Grandfathered in, but transitioned to ordained Deacon or Elder.

• Funding for Theological Education – Theological Education Fund to make loans to students that are forgivable (20 percent for each year of service to the church).

• Retirement for Bishops and Clergy – No mandatory retirement, clergy may choose senior status. Senior clergy not under appointment are annual conference members with voice and vote for seven years. Thereafter, members with voice only.

• Election and Assignment of Bishops – Election process to be determined. Term limits envisioned, perhaps twelve years. Current UM bishops who join the GM Church will continue to serve. Annual conferences without a bishop would have a president pro tempore assigned for the transitional period.

• Appointment Process – Same as UM Church, with enhanced consultation with clergy and local church. Bishops must give a written rationale for appointing a pastor against the wishes of the congregation. Current appointments maintained where possible during transition.

• Guaranteed Appointment – No guaranteed appointment. Bishop must give written rationale for not appointing a clergyperson.

• General Church Governance – Transitional Leadership Council serves as the governing body until the convening General Conference with globally elected delegates.

• General Church Agencies – None mandated. Five transitional commissions suggested (compared with 15 UM agencies).

• Jurisdictions or Central Conferences – Optional, may or may not be formed in a particular area.

• Adaptability of the Discipline – Provisions of the Book of Doctrines and Discipline would apply equally to all geographic areas of the church unless specified. This implies provisions will be more general and consider the global context before being adopted.

• Annual Conference Agencies – Six agencies required, with additional ones at the discretion of the annual conference (compared with 25+ in the UM Church).

• Clergy Accountability – Similar to the UM Church complaint process, with stricter timelines and less discretion in dismissing complaints. Laity would be voting members of committee on investigation.

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

Many more details, as well as the WCA’s proposals following the transitional period, can be found in the chart found at wesleyancovenant.org.

My wife is a marriage and family therapist. One of her favorite questions to provoke dialog is, “How are things changing and how are they remaining the same?” That question is a fitting one to ask, as we head into a key few years of decision-making ahead. Hopefully, this chart can help provide some of the answers.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Photo courtesy of Maxie Dunnam.

By Maxie Dunnam –

Many decades ago, I became intensely interested in the great devotional classics and the collected wisdom of the saints who came before us. Upper Room Ministries had published a collection of little booklets – selections from people whose writings have endured through the centuries. These works expressing Christian faith and life had become classic resources for pilgrims on the Christian way. Those little booklets, providing selections from 29 of these “saints,” were packaged together under the label, Living Selections from the Great Devotional Classics. I simply called it my “box of saints.”

For over 50 years – and even now – that box sits in an obvious place among my books. The box is a bit fragile now, because through the years I have taken out the booklets one by one to read again.

Recently as the coronavirus raged, I pulled the box down again. The “stay at home” orders had come, and it soon became apparent I needed company. I decided that I would live at least part-time with some of the saints again. It was during this time that I compiled a devotional entitled Saints Alive! 30 Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints.

Let me introduce you to three pivotal figures in my spiritual walk.

True devotion. Francis de Sales (1567-1622) wrote of the fundamental nature of devotion and discipline in the Christian life; the meaning of true devotion was one of his primary interests. Anyone who has read the Gospels knows that Jesus’ call is to a narrow way. I don’t know a Christian in all the ages to whom we turn for teaching and inspiration who did not give himself to discipline and devotion.

And de Sales had an inspiring comprehension of devotion. If the Bible said that we are saved by grace through intelligence, some of us would have been too dumb. If we were saved by grace through looks, some of us would be too ugly. If we were saved by grace through education, some of us would be too ignorant. If we were saved by grace through money, some of us would be too poor. But all that is necessary for us to be saved is faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

“True devotion presupposes not a partial but a thorough love of God,” wrote de Sales. “For inasmuch as divine love adorns the soul, it is called grace, making us pleasing to the Divine Majesty; inasmuch as it gives us the strength to do good, it is called charity; but when it is arrived at that degree of perfection by which it makes us do well but also work diligently, frequently, and readily, then it is called devotion.”

Genuine devotion presupposes the love of God; thus, the disciplines we practice must be all for the love of God. This notion is often ignored early in our Christian walk. “Good people who have not as yet attained to devotion fly toward God by their good works, but rarely, slowly, and heavily; but devout souls ascend to him by more frequent, prompt, and lofty flight,” de Sales wrote. He demonstrates that we need to give attention to discipline and devotion to enhance our relationship with Christ, to cultivate a vivid companionship with him. Through discipline and devotion, we learn to be like Christ and to live as he lived.

As I reflect on de Sales’ insights, his influence on my approach to spiritual formation is clear: a dynamic process of receiving through faith and appropriating through commitment, discipline, and action, the living Christ into my own life, to the end that my life will conform to and manifest the reality of Christ’s presence in the world.

The Saints. In the New Testament, “saint” does not refer primarily to the departed; it isn’t even used exclusively for the holy. When Paul writes “the saints,” he means all believers, all who are called to follow Jesus Christ. He addresses the Roman Christians, “to all God’s beloved in Rome who are called to be saints.” He sends his Philippian letter to, “all the saints in Jesus Christ who are at Philippi.” Yet to the Corinthian church, torn by inner fighting, divided over political and social issues, he still addressed them as, “those sanctified in Christ Jesus called to be saints together.”

Evelyn Underhill contended that, as Christians, we are called to be saints, describing saints as not, “examples of a limp surrender. In them we see dynamic personality using all its capacities; and acting with a freedom, originality, complete self-loss in the Divine life. In them will and grace rise and fall together.”

Born in England, Underhill died in 1941. Early in her life, she developed an immense acquaintance with the Christian mystics, writing the huge volume Mysticism. She would likely smile at Frederick Buechner’s description of saints in The Sacred Journey:  “the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

Underhill wrote, “we may allow the saints are specialists; but they are specialists in a career to which all Christians are called. They have achieved the classic status. They are the advance guard of the army; but we are marching the main ranks. The whole army is dedicated to the same supernatural cause; and we ought to envisage it as a whole, to remember that every one of us wears the same uniform as the saints, has access to the same privileges, is taught the same drill and fed the same food. The difference between them and us is a difference in degree, not in kind.”

Her thoughts on prayer are very instructive. “A man of prayer is not necessarily a person who says a number of offices, or abounds in detailed intercessions; but he is a child of God who is and knows himself to be in the deeps of his soul attached to God, and is wholly and entirely guided by the Creative Spirit in his prayer and his work,” Underhill wrote. “It is a description as real and concrete as I can make it, of the only really apostolic life. Every Christian starts with a chance of it; but only a few develop it.”

I became a Christian as a teenager and responded to God’s call to preach a few years later. It was not until I had finished my seminary training and was serving as a pastor, though, that I began to be serious about prayer. I was happily planting a new Methodist congregation in Gulfport, Mississippi; by traditional standards, it was successful. My life and ministry took a turn; my involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and the turmoil that involvement brought, forced something from me I did not have. Prayer and scripture became the center of my life more than ever before. I learned to become bolder in my praying, discovering that when I’m humble, when I see my weakness in its proper light, I can acknowledge my weakness without self-deprecation.

Acknowledging weakness is necessary to appropriate the power of Christ. It is when we are weak that he is strong, when we are inadequate that we can depend on his adequacy, sharing in intercession that will move mountains in the lives of others. Prayer is the source of the power to be obedient in love. Our discipleship, our witness moves on this center: obedience in love. Fervor may depend on circumstance, but prayer gives strength to rise beyond circumstance. It destroys our false desire to be independent of other people or of God. When we pray, we put our arms around another person, around a situation, around the church, around the world, and we hug it to ourselves and to God. When we pray for another, we are united to that person.

“It is only through adoration and attention that we can make our personal discoveries about Him,” writes Underhill. “We gradually and imperceptibly learn more about God by this persistent attitude of humble adoration, than we can hope to do by any amount of mental exploration. In it our soul recaptures, if only for a moment, the fundamental relation of the tiny created spirit with its Eternal Source; the time is well spent in getting this relation and keeping it right. In it we breathe deeply the atmosphere of eternity. We realize, and re-realize, our tininess, and the greatness and steadfastness of God.”

The lowly Jesus. Of all the “saints” with whom we are living in this season, Søren Kierkegaard is perhaps the most unique in personality. In his writing, we discover a very troubled soul: “I have been from childhood on in the grip of an overpowering melancholy, my sole joy being, as far as I can remember, that nobody could discover how unhappy I felt myself to be.” Kierkegaard was born in 1813, the youngest child of a large family. Gloominess and strict loyalty to religion pervaded his environment. He later shared the feeling that he was a victim of “an insane upbringing.” An outsider to the Christian faith might be mystified that such a person could witness to astounding faith in God.

From 1843-46, a period of great creativity and productivity, he wrote a book every three months, besides his journal. He wrote twelve hours a day, testifying, “I have literally lived with God as one lives with a Father. I rise up in the morning and give thanks to God. Then I work. At a set time in the evening I break off and again give thanks to God. Thus do I sleep. Thus do I live.”

Kierkegaard’s writing reflects his reaction to self-reliance, which he believed to be the worst sin. “The smugness of the State Church was illustrative of this self-assurance. Man needs to despair of his inadequacy and be brought face to face with God. Only when man accepts his own spiritual bankruptcy can he be brought before God.”

This conviction shaped the way he approached Jesus; he wrote, “‘Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, I will give you rest.’ Who is the Inviter? Jesus Christ. The Jesus Christ who sits in glory at the right hand of the Father? No. From the seat of his glory he has not spoken one word. It is Jesus Christ in his humiliation, who spoke these words.” Reading this, a gospel hymn comes to mind: “No, Not One.”

There’s not a Friend like the lowly Jesus:

No, not one! no, not one!

None else could heal all our soul’s diseases

No, not one! no, not one!

No friend like Him is so high and holy,

No, not one! no, not one!

And yet no friend is so meek and lowly,

No, not one! no, not one!

Jesus knows all about our struggles,

He will guide till the day is done;

There’s not a friend like the lowly Jesus –

No, not one! no, not one!

I heard this hymn as a teenager in rural Mississippi churches. It was a favorite of my parents and others who were poor; it was easy for them to identify with “the lowly Jesus.” Kierkegaard wanted smug church members to know the nature of the One who extended the invitation “Come unto me” – Jesus in his humiliation.

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

The hymn naming Christ as “the lowly Jesus” dwells on him as our constant companion, a friend who “will guide till the day is done.” Those who hold fast may look in expectation for his glory.

Maxie Dunnam is minister-at-large at Christ United Methodist Church in Memphis, Tennessee. During more than 60 years of ministry he has served both as the president of Asbury Theological Seminary and the world editor of The Upper Room. He is the author of numerous books, including the Workbook on Living Prayer. This excerpt is adapted from Saints Alive! 30 Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints. Reprinted by permission.

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.” “Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”