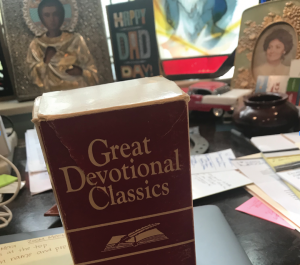

Photo courtesy of Maxie Dunnam.

By Maxie Dunnam –

Many decades ago, I became intensely interested in the great devotional classics and the collected wisdom of the saints who came before us. Upper Room Ministries had published a collection of little booklets – selections from people whose writings have endured through the centuries. These works expressing Christian faith and life had become classic resources for pilgrims on the Christian way. Those little booklets, providing selections from 29 of these “saints,” were packaged together under the label, Living Selections from the Great Devotional Classics. I simply called it my “box of saints.”

For over 50 years – and even now – that box sits in an obvious place among my books. The box is a bit fragile now, because through the years I have taken out the booklets one by one to read again.

Recently as the coronavirus raged, I pulled the box down again. The “stay at home” orders had come, and it soon became apparent I needed company. I decided that I would live at least part-time with some of the saints again. It was during this time that I compiled a devotional entitled Saints Alive! 30 Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints.

Let me introduce you to three pivotal figures in my spiritual walk.

True devotion. Francis de Sales (1567-1622) wrote of the fundamental nature of devotion and discipline in the Christian life; the meaning of true devotion was one of his primary interests. Anyone who has read the Gospels knows that Jesus’ call is to a narrow way. I don’t know a Christian in all the ages to whom we turn for teaching and inspiration who did not give himself to discipline and devotion.

And de Sales had an inspiring comprehension of devotion. If the Bible said that we are saved by grace through intelligence, some of us would have been too dumb. If we were saved by grace through looks, some of us would be too ugly. If we were saved by grace through education, some of us would be too ignorant. If we were saved by grace through money, some of us would be too poor. But all that is necessary for us to be saved is faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

“True devotion presupposes not a partial but a thorough love of God,” wrote de Sales. “For inasmuch as divine love adorns the soul, it is called grace, making us pleasing to the Divine Majesty; inasmuch as it gives us the strength to do good, it is called charity; but when it is arrived at that degree of perfection by which it makes us do well but also work diligently, frequently, and readily, then it is called devotion.”

Genuine devotion presupposes the love of God; thus, the disciplines we practice must be all for the love of God. This notion is often ignored early in our Christian walk. “Good people who have not as yet attained to devotion fly toward God by their good works, but rarely, slowly, and heavily; but devout souls ascend to him by more frequent, prompt, and lofty flight,” de Sales wrote. He demonstrates that we need to give attention to discipline and devotion to enhance our relationship with Christ, to cultivate a vivid companionship with him. Through discipline and devotion, we learn to be like Christ and to live as he lived.

As I reflect on de Sales’ insights, his influence on my approach to spiritual formation is clear: a dynamic process of receiving through faith and appropriating through commitment, discipline, and action, the living Christ into my own life, to the end that my life will conform to and manifest the reality of Christ’s presence in the world.

The Saints. In the New Testament, “saint” does not refer primarily to the departed; it isn’t even used exclusively for the holy. When Paul writes “the saints,” he means all believers, all who are called to follow Jesus Christ. He addresses the Roman Christians, “to all God’s beloved in Rome who are called to be saints.” He sends his Philippian letter to, “all the saints in Jesus Christ who are at Philippi.” Yet to the Corinthian church, torn by inner fighting, divided over political and social issues, he still addressed them as, “those sanctified in Christ Jesus called to be saints together.”

Evelyn Underhill contended that, as Christians, we are called to be saints, describing saints as not, “examples of a limp surrender. In them we see dynamic personality using all its capacities; and acting with a freedom, originality, complete self-loss in the Divine life. In them will and grace rise and fall together.”

Born in England, Underhill died in 1941. Early in her life, she developed an immense acquaintance with the Christian mystics, writing the huge volume Mysticism. She would likely smile at Frederick Buechner’s description of saints in The Sacred Journey:  “the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

Underhill wrote, “we may allow the saints are specialists; but they are specialists in a career to which all Christians are called. They have achieved the classic status. They are the advance guard of the army; but we are marching the main ranks. The whole army is dedicated to the same supernatural cause; and we ought to envisage it as a whole, to remember that every one of us wears the same uniform as the saints, has access to the same privileges, is taught the same drill and fed the same food. The difference between them and us is a difference in degree, not in kind.”

Her thoughts on prayer are very instructive. “A man of prayer is not necessarily a person who says a number of offices, or abounds in detailed intercessions; but he is a child of God who is and knows himself to be in the deeps of his soul attached to God, and is wholly and entirely guided by the Creative Spirit in his prayer and his work,” Underhill wrote. “It is a description as real and concrete as I can make it, of the only really apostolic life. Every Christian starts with a chance of it; but only a few develop it.”

I became a Christian as a teenager and responded to God’s call to preach a few years later. It was not until I had finished my seminary training and was serving as a pastor, though, that I began to be serious about prayer. I was happily planting a new Methodist congregation in Gulfport, Mississippi; by traditional standards, it was successful. My life and ministry took a turn; my involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and the turmoil that involvement brought, forced something from me I did not have. Prayer and scripture became the center of my life more than ever before. I learned to become bolder in my praying, discovering that when I’m humble, when I see my weakness in its proper light, I can acknowledge my weakness without self-deprecation.

Acknowledging weakness is necessary to appropriate the power of Christ. It is when we are weak that he is strong, when we are inadequate that we can depend on his adequacy, sharing in intercession that will move mountains in the lives of others. Prayer is the source of the power to be obedient in love. Our discipleship, our witness moves on this center: obedience in love. Fervor may depend on circumstance, but prayer gives strength to rise beyond circumstance. It destroys our false desire to be independent of other people or of God. When we pray, we put our arms around another person, around a situation, around the church, around the world, and we hug it to ourselves and to God. When we pray for another, we are united to that person.

“It is only through adoration and attention that we can make our personal discoveries about Him,” writes Underhill. “We gradually and imperceptibly learn more about God by this persistent attitude of humble adoration, than we can hope to do by any amount of mental exploration. In it our soul recaptures, if only for a moment, the fundamental relation of the tiny created spirit with its Eternal Source; the time is well spent in getting this relation and keeping it right. In it we breathe deeply the atmosphere of eternity. We realize, and re-realize, our tininess, and the greatness and steadfastness of God.”

The lowly Jesus. Of all the “saints” with whom we are living in this season, Søren Kierkegaard is perhaps the most unique in personality. In his writing, we discover a very troubled soul: “I have been from childhood on in the grip of an overpowering melancholy, my sole joy being, as far as I can remember, that nobody could discover how unhappy I felt myself to be.” Kierkegaard was born in 1813, the youngest child of a large family. Gloominess and strict loyalty to religion pervaded his environment. He later shared the feeling that he was a victim of “an insane upbringing.” An outsider to the Christian faith might be mystified that such a person could witness to astounding faith in God.

From 1843-46, a period of great creativity and productivity, he wrote a book every three months, besides his journal. He wrote twelve hours a day, testifying, “I have literally lived with God as one lives with a Father. I rise up in the morning and give thanks to God. Then I work. At a set time in the evening I break off and again give thanks to God. Thus do I sleep. Thus do I live.”

Kierkegaard’s writing reflects his reaction to self-reliance, which he believed to be the worst sin. “The smugness of the State Church was illustrative of this self-assurance. Man needs to despair of his inadequacy and be brought face to face with God. Only when man accepts his own spiritual bankruptcy can he be brought before God.”

This conviction shaped the way he approached Jesus; he wrote, “‘Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, I will give you rest.’ Who is the Inviter? Jesus Christ. The Jesus Christ who sits in glory at the right hand of the Father? No. From the seat of his glory he has not spoken one word. It is Jesus Christ in his humiliation, who spoke these words.” Reading this, a gospel hymn comes to mind: “No, Not One.”

There’s not a Friend like the lowly Jesus:

No, not one! no, not one!

None else could heal all our soul’s diseases

No, not one! no, not one!

No friend like Him is so high and holy,

No, not one! no, not one!

And yet no friend is so meek and lowly,

No, not one! no, not one!

Jesus knows all about our struggles,

He will guide till the day is done;

There’s not a friend like the lowly Jesus –

No, not one! no, not one!

I heard this hymn as a teenager in rural Mississippi churches. It was a favorite of my parents and others who were poor; it was easy for them to identify with “the lowly Jesus.” Kierkegaard wanted smug church members to know the nature of the One who extended the invitation “Come unto me” – Jesus in his humiliation.

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

The hymn naming Christ as “the lowly Jesus” dwells on him as our constant companion, a friend who “will guide till the day is done.” Those who hold fast may look in expectation for his glory.

Maxie Dunnam is minister-at-large at Christ United Methodist Church in Memphis, Tennessee. During more than 60 years of ministry he has served both as the president of Asbury Theological Seminary and the world editor of The Upper Room. He is the author of numerous books, including the Workbook on Living Prayer. This excerpt is adapted from Saints Alive! 30 Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints. Reprinted by permission.

0 Comments