by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Photo courtesy of Maxie Dunnam.

By Maxie Dunnam –

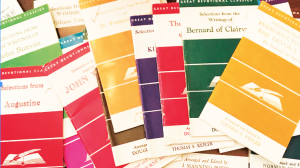

Many decades ago, I became intensely interested in the great devotional classics and the collected wisdom of the saints who came before us. Upper Room Ministries had published a collection of little booklets – selections from people whose writings have endured through the centuries. These works expressing Christian faith and life had become classic resources for pilgrims on the Christian way. Those little booklets, providing selections from 29 of these “saints,” were packaged together under the label, Living Selections from the Great Devotional Classics. I simply called it my “box of saints.”

For over 50 years – and even now – that box sits in an obvious place among my books. The box is a bit fragile now, because through the years I have taken out the booklets one by one to read again.

Recently as the coronavirus raged, I pulled the box down again. The “stay at home” orders had come, and it soon became apparent I needed company. I decided that I would live at least part-time with some of the saints again. It was during this time that I compiled a devotional entitled Saints Alive! 30 Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints.

Let me introduce you to three pivotal figures in my spiritual walk.

True devotion. Francis de Sales (1567-1622) wrote of the fundamental nature of devotion and discipline in the Christian life; the meaning of true devotion was one of his primary interests. Anyone who has read the Gospels knows that Jesus’ call is to a narrow way. I don’t know a Christian in all the ages to whom we turn for teaching and inspiration who did not give himself to discipline and devotion.

And de Sales had an inspiring comprehension of devotion. If the Bible said that we are saved by grace through intelligence, some of us would have been too dumb. If we were saved by grace through looks, some of us would be too ugly. If we were saved by grace through education, some of us would be too ignorant. If we were saved by grace through money, some of us would be too poor. But all that is necessary for us to be saved is faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

“True devotion presupposes not a partial but a thorough love of God,” wrote de Sales. “For inasmuch as divine love adorns the soul, it is called grace, making us pleasing to the Divine Majesty; inasmuch as it gives us the strength to do good, it is called charity; but when it is arrived at that degree of perfection by which it makes us do well but also work diligently, frequently, and readily, then it is called devotion.”

Genuine devotion presupposes the love of God; thus, the disciplines we practice must be all for the love of God. This notion is often ignored early in our Christian walk. “Good people who have not as yet attained to devotion fly toward God by their good works, but rarely, slowly, and heavily; but devout souls ascend to him by more frequent, prompt, and lofty flight,” de Sales wrote. He demonstrates that we need to give attention to discipline and devotion to enhance our relationship with Christ, to cultivate a vivid companionship with him. Through discipline and devotion, we learn to be like Christ and to live as he lived.

As I reflect on de Sales’ insights, his influence on my approach to spiritual formation is clear: a dynamic process of receiving through faith and appropriating through commitment, discipline, and action, the living Christ into my own life, to the end that my life will conform to and manifest the reality of Christ’s presence in the world.

The Saints. In the New Testament, “saint” does not refer primarily to the departed; it isn’t even used exclusively for the holy. When Paul writes “the saints,” he means all believers, all who are called to follow Jesus Christ. He addresses the Roman Christians, “to all God’s beloved in Rome who are called to be saints.” He sends his Philippian letter to, “all the saints in Jesus Christ who are at Philippi.” Yet to the Corinthian church, torn by inner fighting, divided over political and social issues, he still addressed them as, “those sanctified in Christ Jesus called to be saints together.”

Evelyn Underhill contended that, as Christians, we are called to be saints, describing saints as not, “examples of a limp surrender. In them we see dynamic personality using all its capacities; and acting with a freedom, originality, complete self-loss in the Divine life. In them will and grace rise and fall together.”

Born in England, Underhill died in 1941. Early in her life, she developed an immense acquaintance with the Christian mystics, writing the huge volume Mysticism. She would likely smile at Frederick Buechner’s description of saints in The Sacred Journey:  “the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

Underhill wrote, “we may allow the saints are specialists; but they are specialists in a career to which all Christians are called. They have achieved the classic status. They are the advance guard of the army; but we are marching the main ranks. The whole army is dedicated to the same supernatural cause; and we ought to envisage it as a whole, to remember that every one of us wears the same uniform as the saints, has access to the same privileges, is taught the same drill and fed the same food. The difference between them and us is a difference in degree, not in kind.”

Her thoughts on prayer are very instructive. “A man of prayer is not necessarily a person who says a number of offices, or abounds in detailed intercessions; but he is a child of God who is and knows himself to be in the deeps of his soul attached to God, and is wholly and entirely guided by the Creative Spirit in his prayer and his work,” Underhill wrote. “It is a description as real and concrete as I can make it, of the only really apostolic life. Every Christian starts with a chance of it; but only a few develop it.”

I became a Christian as a teenager and responded to God’s call to preach a few years later. It was not until I had finished my seminary training and was serving as a pastor, though, that I began to be serious about prayer. I was happily planting a new Methodist congregation in Gulfport, Mississippi; by traditional standards, it was successful. My life and ministry took a turn; my involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and the turmoil that involvement brought, forced something from me I did not have. Prayer and scripture became the center of my life more than ever before. I learned to become bolder in my praying, discovering that when I’m humble, when I see my weakness in its proper light, I can acknowledge my weakness without self-deprecation.

Acknowledging weakness is necessary to appropriate the power of Christ. It is when we are weak that he is strong, when we are inadequate that we can depend on his adequacy, sharing in intercession that will move mountains in the lives of others. Prayer is the source of the power to be obedient in love. Our discipleship, our witness moves on this center: obedience in love. Fervor may depend on circumstance, but prayer gives strength to rise beyond circumstance. It destroys our false desire to be independent of other people or of God. When we pray, we put our arms around another person, around a situation, around the church, around the world, and we hug it to ourselves and to God. When we pray for another, we are united to that person.

“It is only through adoration and attention that we can make our personal discoveries about Him,” writes Underhill. “We gradually and imperceptibly learn more about God by this persistent attitude of humble adoration, than we can hope to do by any amount of mental exploration. In it our soul recaptures, if only for a moment, the fundamental relation of the tiny created spirit with its Eternal Source; the time is well spent in getting this relation and keeping it right. In it we breathe deeply the atmosphere of eternity. We realize, and re-realize, our tininess, and the greatness and steadfastness of God.”

The lowly Jesus. Of all the “saints” with whom we are living in this season, Søren Kierkegaard is perhaps the most unique in personality. In his writing, we discover a very troubled soul: “I have been from childhood on in the grip of an overpowering melancholy, my sole joy being, as far as I can remember, that nobody could discover how unhappy I felt myself to be.” Kierkegaard was born in 1813, the youngest child of a large family. Gloominess and strict loyalty to religion pervaded his environment. He later shared the feeling that he was a victim of “an insane upbringing.” An outsider to the Christian faith might be mystified that such a person could witness to astounding faith in God.

From 1843-46, a period of great creativity and productivity, he wrote a book every three months, besides his journal. He wrote twelve hours a day, testifying, “I have literally lived with God as one lives with a Father. I rise up in the morning and give thanks to God. Then I work. At a set time in the evening I break off and again give thanks to God. Thus do I sleep. Thus do I live.”

Kierkegaard’s writing reflects his reaction to self-reliance, which he believed to be the worst sin. “The smugness of the State Church was illustrative of this self-assurance. Man needs to despair of his inadequacy and be brought face to face with God. Only when man accepts his own spiritual bankruptcy can he be brought before God.”

This conviction shaped the way he approached Jesus; he wrote, “‘Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, I will give you rest.’ Who is the Inviter? Jesus Christ. The Jesus Christ who sits in glory at the right hand of the Father? No. From the seat of his glory he has not spoken one word. It is Jesus Christ in his humiliation, who spoke these words.” Reading this, a gospel hymn comes to mind: “No, Not One.”

There’s not a Friend like the lowly Jesus:

No, not one! no, not one!

None else could heal all our soul’s diseases

No, not one! no, not one!

No friend like Him is so high and holy,

No, not one! no, not one!

And yet no friend is so meek and lowly,

No, not one! no, not one!

Jesus knows all about our struggles,

He will guide till the day is done;

There’s not a friend like the lowly Jesus –

No, not one! no, not one!

I heard this hymn as a teenager in rural Mississippi churches. It was a favorite of my parents and others who were poor; it was easy for them to identify with “the lowly Jesus.” Kierkegaard wanted smug church members to know the nature of the One who extended the invitation “Come unto me” – Jesus in his humiliation.

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

The hymn naming Christ as “the lowly Jesus” dwells on him as our constant companion, a friend who “will guide till the day is done.” Those who hold fast may look in expectation for his glory.

Maxie Dunnam is minister-at-large at Christ United Methodist Church in Memphis, Tennessee. During more than 60 years of ministry he has served both as the president of Asbury Theological Seminary and the world editor of The Upper Room. He is the author of numerous books, including the Workbook on Living Prayer. This excerpt is adapted from Saints Alive! 30 Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints. Reprinted by permission.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Worship time at the 2021 New Room Conference in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Photo courtesy of New Room.

In the midst of chaotic and frustrating times within United Methodism, there is a simultaneous larger pan-Wesleyan movement calling for a renewal of minds and hearts. Over a three-day event in late September, more than 2,100 attended Seedbed’s New Room Conference in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. An additional 600 participated through livestreaming.

Through break-out sessions and plenary addresses, nationally-recognized speakers such as Rich Villodas, Jo Saxton, and Todd Hunter challenged and inspired the assembly. Platform presentations also featured familiar names to United Methodists such as Kevin Watson, Carolyn Moore, and Timothy Tennent.

Despite dozens of book titles under its imprint, the Rev. J.D. Walt insisted that Seedbed, the host of the annual New Room gathering, is not merely a publishing company. “Publishing is not an identity, it’s a strategy. We’re an awakening company,” the Seedbed leader told the assembly.

In our contemporary culture, the challenges facing the Christian church are daunting. “If you listen close enough, there is a generation that is leaving the church – a generation that some are not just calling the ‘nones,’ but now calling the ‘dones,’” said the Rev. Tara Beth Leach, author of Radiant Church: Restoring the Credibility of Our Witness. Particulary on social media, there has been a notable trend of declarations from former churchgoers “deconstructing” their faith.

“If you listen close enough to this generation that is down this path of deconstruction, deconstruction, deconstruction … without any end,” said Leach. “They are not necessarily deconstructing God, but us – the toxic systems and idolatrous systems that we have created.”

“If you listen close enough to this generation that is down this path of deconstruction, deconstruction, deconstruction … without any end,” said Leach. “They are not necessarily deconstructing God, but us – the toxic systems and idolatrous systems that we have created.”

Photos on this spread: New Room participants pray and worship during the three-day event. Photos courtesy of Seedbed.

“Returning to church as we have known it, cycling back, is simply not an option,” said the Rev. David Thomas, senior advisor to New Room, in his opening address. “This is where we’re helped by listening to the young. Emerging Christian leaders, these resilient millennial and GenZ Christians, don’t want our church. They’re not rude about it. But they’re clear: they don’t want our org charts and structures, our career ladders and programming, our metrics and trophies. Emerging adults have come of age in a time when church is seen in society as the problem, not viewed positively or even as neutral. The young live in a world that perceives Christianity as undermining the social good.”

Above: Seedbed leaders J.D. Walt (left) and Mark Benjamin address conference participants. Photo courtesy of Seedbed.

Leach believes this a critical time for the church to engage in self-examination. “Perhaps more than ever it’s time we take our finger and point it back inward and ask, ‘Lord, what have we done? What have we abandoned? What have we participated in that has led to this place of a diminished witness?”

Not without hope, Leach believes that the church still has an opportunity to provide a compelling witness. “We are still at this watershed moment,” she said.

The gospel of Jesus Christ remains a magnetic message. “The body of Christ is still the best vehicle the world has for translating the glorious good news of Jesus Christ to a lost and hurting world,” the Rev. Carolyn Moore, pastor of Mosaic Church in Evans, Georgia, and author of Supernatural, told the conference.

Unified Wesleyan Witness. From the very beginning, New Room and Seedbed has operated as a network for Wesleyans across a multi-denomination spectrum that wants to see a spiritual awakening in the United States and around the world. “We are an awakening platform and we are just trying to give it away,” Walt said. “As far and as wide as anybody will receive it.” He slightly modified the familiar appeal of Methodism’s founder John Wesley: “If your heart is as ours, let’s just take each other’s hands and let’s sow for awakening.”

– Good News Media Service.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“The church lives between two advents. Jesus Christ has come; Jesus Christ will come,” writes Fleming Rutledge. “We do not know the day or the hour. If you find this tension almost unbearable at times, then you understand the Christian life.” Photo: Shutterstock.

By Fleming Rutledge –

It is dark early at this time of year and that reminds us of a darkness in our world. There is Christmas tinsel in the streets and Christmas music on the radio, but there is a cheapness at the core. The clock on the bank says it is day, but the hands on the church clock point to midnight.

It is Advent – the deepest place in the church year.

Advent – for the world, is a time of counting shopping days before Christmas. Advent – for the church, it is the season of the shadows, the season of “the works of darkness,” the season in which the church looks straight down into its own heart and finds there … the absence of God.

Now. Come back with me into the very first century AD when the Gospel of Mark was being put together. The young Christian church is going through a crisis of identity. It hears mocking laughter outside, voices saying, “Where is your King? You thought he was coming back, but he has not returned. You have made a very stupid mistake. How can you live without your Lord? He has abandoned you – for this, you want to risk your lives?”

And in its perplexity, the young church repeated a story to itself, a story once told by Jesus of Nazareth. It is one of the so-called crisis parables. It is the Gospel for the first Sunday in Advent, the parable of the doorkeeper.

There is a great household with many family members and many servants. There is a master, who established the household in the first place and gave it its reason for being; he is the one who gathered its members and assigned a place to each. It is he who put the whole operation in motion, who gave shape and direction to its existence. The master has gone away, but his orders are that there is to be a watch at the door, a constant alert. This is the command to the doorkeeper – “Stay awake” – but what he has said to the doorkeeper he says to everyone: “Keep awake.” This state of readiness is to be maintained through the ceaseless vigilance of each family member and servant, each in his own work, until the master returns.

Perhaps you begin to feel the tension in the atmosphere of this parable. Were it not for the master, the household would have no reason for existing; yet he is away. The expectation of his return is the moving force behind all the activity that takes place; yet no one knows when the return will be. Everybody has been ordered to keep awake; yet the days and months and years pass, and still he does not come. Over and over again, the household repeats to itself the charge that it was given – “If he comes suddenly, he must not find us asleep.”

The heartbeat of the parable is strong and accelerated – it is a parable of crisis. It is the story of the church, living in a crisis for two thousand years. The church calendar is not the same as the world’s calendar. The Advent clock points to an hour that is later than the clock on the bank. There is a knocking at the door! Take heed, watch – your Lord and Master may be standing at the gate this very moment. Keep awake, for if he comes suddenly, he must not find you asleep. “A thousand ages in his sight are like an evening gone” (Isaac Watts, “O God, Our Help in Ages Past”). There is no way for the church to adjust its calendar to the world’s calendar.

The church is not part of contemporary culture, and never should have been. The church keeps her own deep inner rhythms. New Testament time is different from the world’s time; Saint Paul says, “My friends, the time we live in will not last long …. For the whole frame of this world is passing away” (1 Cor. 7:29, 31). New Testament time is a million years compressed into a single instant – and the time is now. “The hour cometh, and now is” (John 4:23). There is no way to alleviate the overwhelming tension produced by the Advent clock; the only way to be faithful is to be faithful at each moment. “Keep awake, for you do not know when the master of the house is coming.”

The church lives in Advent. That is to say, the church lives between two advents. Jesus Christ has come; Jesus Christ will come. We do not know the day or the hour. If you find this tension almost unbearable at times, then you understand the Christian life. We live at what the New Testament depicts as the turn of the ages. In Jesus Christ, the kingdom of God is in head-on collision with the powers of darkness. The point of impact is the place where Christians take their stand. That is why it hurts. That’s why the church has to take a beating. This is what Scripture tells us. No wonder there are so many who fall away; the church is located precisely where the battle line is drawn.

It is the Advent clock that tells the church what time it is. The church that keeps Advent is the church that is most truly herself. The church is not supposed to be prosperous and commonable and established. It is Advent – it is dark and lonely and cold, and the master is away from home. Yet he will come. Keep awake.

He came among us once as a stranger, and we put him on a cross. He comes among us now, in the guise of the stranger at the door. He will come in the future, not as a stranger, but as the King in his glory, and “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow” (Phil. 2:10). “The coming of the Lord is at hand,” says Saint James. “Behold, the Judge is standing at the doors” (James 5:8-9). Keep awake, then … if he comes suddenly, he must not find you asleep.

He came among us once as a stranger, and we put him on a cross. He comes among us now, in the guise of the stranger at the door. He will come in the future, not as a stranger, but as the King in his glory, and “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow” (Phil. 2:10). “The coming of the Lord is at hand,” says Saint James. “Behold, the Judge is standing at the doors” (James 5:8-9). Keep awake, then … if he comes suddenly, he must not find you asleep.

Fleming Rutledge is an Episcopal priest, best-selling author, and a widely revered preacher. Her many books include The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ. The article is taken from her year-long devotional book, Means of Grace: A Year of Weekly Devotions (Eerdmans).

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Hand colored lithograph of John Wesley preaching on his father’s grave in the church yard at Epworth in 1742. Currier and Ives artwork. Library of Congress.

“John Wesley and Karl Marx, unmistakably, are the two most influential characters of all modern history,” wrote social historian Dr. J. Wesley Bready (1887-1953) in his colorful and intriguing assessment of the ramifications of the theological and spiritual revival in Wesley-era England. Most recently, Regent College republished Bready’s England Before and After Wesley: The Evangelical Revival and Social Reform, originally published in 1938.

Wesley’s “vital religion” was far more transformative – both individually and societally – than what Marx would have dismissed as the “opiate of the people.” Wesley and his followers addressed issues such as prison reform, education, poverty, health care, human slavery, orphanages, literacy, animal cruelty, and chronic alcoholism. What follows are a few of our favorite excerpts from Bready’s book. –Good News

Passion to be used by God: “Wesley’s supreme purpose was to make men vitally conscious of God. He therefore had no desire to dictate the intellectual niceties associated with the divine work of redemption; rather was he actuated by an impelling passion to be used of God, as a humble but active instrument, in the work of redemption. With prophetic insight he recognized the insidious demons which were luring millions of his countrymen into the tangled labyrinths of moral corruption and spiritual death – and challenging the sway of those demons, he set about to release the victims from their woeful plight. He saw the ecclesiastical machinery of his generation rusty and clogged with dust; he chafed to cleanse it and set it in motion, for the redemption of the general populace. His purpose was not to formulate a new theology or a new theory of Church or State, but to touch dead bones with the breath of spiritual power, and make them live; to release the winds of heaven, that they might blow upon the ashy embers of religion and kindle a purging, illuminating fire of righteousness and truth. He would substitute for the bondage of sin, the liberty, individual and social, of men new-born after the similitude of Christ. He would revive creative, life-giving Faith.”

Attacking the Revival: “During the first two or three decades of the Revival the ugly, riotous interference of mobs was more or less continuous. On innumerable occasions, the meetings of the Wesleys, Whitefield, and many itinerant preachers were attacked by drunken, brawling rabbles armed with such formidable means of assault as clubs, whips, clods, bricks, staves, stones, stink-bombs, wildfire, and rotten eggs. Sometimes they procured a bull and drove him into the midst of an open air congregation; sometimes they contented themselves by performing with bells, horns, drums, pans and such like, to deaden the preacher’s voice. Frequently, when goaded by a violent leader, they resorted to every available means of attack; and not infrequently they expended their fury in burning or tearing down the houses, and destroying or stealing the furniture and possessions, of the Revival’s followers.”

Amazing grace: “Wesley, the Evangelist, was a man possessed of amazing grace. Never did he lose his temper; and always was he prepared to endure a blow, if the dealing of it would relieve the hysteria of his assailant. Repeatedly, when struck by a stone or cudgel, he quietly wiped away the blood and went on preaching without so much as a frown on his face. He loved his enemies; and do what they would, they could not make him discourteous or angry. … In danger, Wesley had taught his followers to think of the Christ before Pilate, of the Son of God before a raging, crucifying mob. Thus it was, that Wesley’s serenity first broke, and later won, the heart of many a mob-leader and ruthless enemy – thus it was, too, that many a one-time brute came to be transformed into a gentle, saintly class-leader and understanding shepherd of souls.”

Amazing grace: “Wesley, the Evangelist, was a man possessed of amazing grace. Never did he lose his temper; and always was he prepared to endure a blow, if the dealing of it would relieve the hysteria of his assailant. Repeatedly, when struck by a stone or cudgel, he quietly wiped away the blood and went on preaching without so much as a frown on his face. He loved his enemies; and do what they would, they could not make him discourteous or angry. … In danger, Wesley had taught his followers to think of the Christ before Pilate, of the Son of God before a raging, crucifying mob. Thus it was, that Wesley’s serenity first broke, and later won, the heart of many a mob-leader and ruthless enemy – thus it was, too, that many a one-time brute came to be transformed into a gentle, saintly class-leader and understanding shepherd of souls.”

J. Wesley Bready Ph.D. was a noted sociologist, lecturer, and scholar. These excerpts are from his book Before and After Wesley: The Evangelical Revival and Social Reform (the original edition was published in 1938).

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“John Wesley represents an intriguing synthesis of old and new,” wrote Howard Snyder in Radical Wesley, “conservative and radical, tradition and innovation that can spark greater clarity in today’s new quest to be radically Christian.” Photo: Shutterstock.

By Winfield Bevins –

It’s easy for contemporary Christians to think that John Wesley, the great revivalist and leader of the Great Awakening, was opposed to church tradition altogether. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, he was a high churchman who loved church tradition, the sacraments, and the Anglican liturgy. He used the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, which contains orders of services, ancient creeds, communal prayers, and a lectionary. Wesley said, “I believe there is no Liturgy in the world, either in ancient or modern language, which breathes more of a solid, scriptural, rational piety than the Common Prayer of the Church of England.”

While at Oxford, Wesley and his brother Charles were accused of being “sacramentalists” because of their insistence upon taking communion regularly. It is said that Wesley took the Lord’s Supper at least once every four to five days, and he encouraged the Methodists to celebrate the Lord’s Supper weekly. Wesley said, “It is the duty of every Christian to receive the Lord’s Supper as often as he can” (“The Duty of Constant Communion”). These are hardly the words of a non-traditionalist.

In many ways, early Methodism could be described as a movement that was founded on tradition and innovation. Wesley traced the Methodist genealogy back to the “old religion,” describing Methodism as “the old religion, the religion of the Bible, the religion of the primitive Church, the religion of the Church of England.” For Wesley, Methodism was not something new, but another link in an unbroken chain of true religion, a religion of the heart, which was “no other than love, the love of God and of all mankind” (“On Laying the Foundation”).

“Wesley’s ecclesiology was a working synthesis of old and new, tradition and innovation…True renewal in the church always weds new insights, ideas, and methods with the best elements of history,” writes Howard Snyder in Radical Wesley. “And true renewal is always a return, at the most basic level, to the image of the church as presented in Scripture and as lived out in a varying mosaic of faithfulness and unfaithfulness down through history. John Wesley represents an intriguing synthesis of old and new, conservative and radical, tradition and innovation that can spark greater clarity in today’s new quest to be radically Christian.”

This return to a more primitive form and practice of Christianity primarily meant returning to the spiritual vitality that was characteristic of the book of Acts and the early church. Wesley and the early Methodists had a vision to recapture a “contagious faith” and to spread it around the world: “Scriptural Christianity, as beginning to exist in individuals; as spreading from one to another; as covering the earth” (“Scriptural Christianity”).

It clearly states on Wesley’s tombstone, that the heart of the Wesleyan revival was the rediscovery of “the pure apostolic doctrines and practices of the early church.” But Wesley did more than read and study the past. He took what he learned and reapplied it, contextualizing it to his own time and place. More than that, he used what he learned to create a disciple-making movement that equipped and empowered thousands of people to join in God’s mission.

The Tension of Tradition and Innovation. One of the secrets of the success of Wesley’s movement was his ability to maintain a dynamic synthesis of old and new, tradition and innovation. While he wasn’t against tradition, Wesley was opposed to dead, dry religion, cold ritualism, and the clericalism that discouraged non-ordained people from being involved in the life of the ministry, all of which had become widespread in the Church of England in the eighteenth century.

The Wesleyan synthesis could perhaps best be viewed as a tension between the embrace of tradition and the need for innovation. While Wesley was a traditional high church Anglican priest who honored church tradition, at the same time, he was an apostolic leader who was willing to innovate, willing to bring change to the structure and methods of the church in order to see the gospel shared and lives changed.

While Wesley honored this tradition, he was not bound by it. He was far more concerned with saving souls, and he believed that the Lord was doing an extraordinary thing by raising up the Methodists and calling non-ordained men and women to preach and serve as leaders in the church. This, perhaps more than anything else, was why Wesley faced such opposition to his work. His embrace of non-ordained people to preach and lead bypassed the institutional hierarchy and upset the status quo. His empowerment of an army of non-ordained women and men was nothing short of revolutionary at a time when the church relied almost solely on clergy to accomplish Christ’s mission.

Wesley worked to keep the old and the new in tension. He began to envision two kinds of ministerial orders: the ordinary Anglican clergy and the extraordinary Methodist preachers. Wesley saw a role for Anglican ministers in providing pastoral oversight of a congregation and administering the sacraments, while the purpose of the extraordinary Methodist preachers was preaching and evangelizing the lost.

Wesley used the Scriptures to aid him in embracing the tension he held between tradition and innovation, between the old and the new. He continued to believe in the need for the ordinary and established Anglican clergy, but he believed that there was an equally significant role for the non-ordained preachers and workers of the Methodist movement. The church was filled with ordained clergy, yet it was not meeting the need of the world to hear the gospel message.

What was needed was an army of lay preachers and evangelists who would preach the good news at every highway and in the hedges. To this vision, Wesley was willing to give his life, dedicating his time and energy to empower a new and extraordinary order of ministry. The result of Wesley’s embrace of tradition and innovation was the birth of one of the greatest Christian movements the world has ever known.

Tradition and Innovation Today. Wesley reminds us that we need tradition and innovation to face the challenges and complexities of today’s world. We do not need innovation at the expense of tradition. Rather, we need innovation that is rooted in tradition. I believe the future mission of the church will be found on the road where the past and the present meet in a re-traditioning that embraces the best of tradition for the sake of the future through tradition and innovation.

The combination of tradition and innovation does not mean compromising time-honored essentials of orthodoxy or church tradition, but rather bringing those essentials into dialogue with the present realities of the church in a beautiful convergence of old and new. I believe the church of the future will need to be rooted in Scripture, tradition, liturgy, and sacraments, while at the same time fully engage in mission at the intersection of the gospel and culture.

By using the term “tradition,” I do not mean tradition with a capital T, as in Roman Catholicism or Lutheranism, but rather I am referring to tradition with a lowercase t, as in what has been common to all Christians in all ages, especially during the first five centuries of the church.

Maybe you’re thinking to yourself, “Isn’t tradition just dead religion?” We need to distinguish between tradition and traditionalism.

Historian Jaroslav Pelikan describes the difference between tradition and traditionalism. “Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living,” he said. “Tradition lives in conversation with the past, while remembering where we are and when we are and that it is we who have to decide. Traditionalism supposes that nothing should ever be done for the first time, so all that is needed to solve any problem is to arrive at the supposedly unanimous testimony of this homogenized tradition.”

With Wesley, I believe the church of the future will be one that is rooted in tradition and innovation. The recovery of tradition doesn’t mean that we should try to relive the past; it’s about retrieving it and appropriating it into the context of life in twenty-first century North America. I am not advocating reverting back to “the good ol’ days,” but proposing a way for the past, present, and future to come together for a new generation that is rooted in tradition and innovation. I believe that the future of the church not only lies in the traditions of the past, but in the unique implementation of these concepts in our world today.

In his book You Are What You Love, James K.A. Smith calls this integration “tradition for innovation.” He reminds us that tradition should be seen as a resource to foster cultural innovation because it provides us with rich imaginative practices that are rooted in historic Christian worship. Here are some of Smith’s examples of how liturgy fosters a fresh missional imagination:

“Kneeling in confession and voicing ‘the things we have done and the things we have left undone …’ tangibly and viscerally impresses upon us the brokenness of our world and humbles our own pretensions;

“Pledging allegiance in the Creed is a political act – a reminder that we are citizens of a coming kingdom, curtailing our temptation to over identify with any configuration of the earthly city;

“The rite of baptism, where the congregation vows to help raise a child alongside the parents, is just the liturgical formation we need to be a people who can support those raising children with intellectual disabilities or other special needs;

“Sitting at the Lord’s Table with the risen King, where all are invited to eat, is a tactile reminder of the just, abundant world that God longs for.”

I believe this is one of great needs in the world today: holding tradition and innovation, old and new, together in a dynamic way. The recovery of tradition and innovation was at the heart of the Wesleyan revival. Wesley wanted to recover the old religion and connect his generation with the early church and its teachings, but Methodism was also something new, contextualized for his time and place, and Wesley was able to give old truth fresh expression. When he spoke about recovering “Scriptural Christianity,” Wesley meant a return to the pure, undefiled “religion of the Bible, the religion of the primitive church” (“On Laying the Foundations.”)

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

Winfield Bevins the Director of Church Planting at Asbury Theological Seminary. He also is a frequent conference speaker and author. Some of his recent books include Ever Ancient, Ever New: The Allure of Liturgy for a New Generation and Marks of a Movement: What the Church Today Can Learn from the Wesleyan Revival. This essay originally appeared on Firebrand (firebrandmag.com) and is reprinted by permission.

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”

“the foolish ones and wise ones, the shy ones and overbearing ones, the broken ones and the whole ones, the despots and tosspots and crackpots of our lives who, one way or another, have helped us toward whatever little we may have, or ever hope to have, of some kind of seedy sainthood of our own.” Yet her call is serious. “The saints abound in fellowship and service, because they are abandoned to the Spirit, and see life in relation to God, instead of God in relation to life.”  “Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

“Is this Jesus Christ not always the same? Yes, the same yesterday and today, the same that 1800 years ago humbled himself and took the form of a servant, the Jesus Christ who uttered these words of invitation.”

“If you listen close enough to this generation that is down this path of deconstruction, deconstruction, deconstruction … without any end,” said Leach. “They are not necessarily deconstructing God, but us – the toxic systems and idolatrous systems that we have created.”

“If you listen close enough to this generation that is down this path of deconstruction, deconstruction, deconstruction … without any end,” said Leach. “They are not necessarily deconstructing God, but us – the toxic systems and idolatrous systems that we have created.”

He came among us once as a stranger, and we put him on a cross. He comes among us now, in the guise of the stranger at the door. He will come in the future, not as a stranger, but as the King in his glory, and “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow” (Phil. 2:10). “The coming of the Lord is at hand,” says Saint James. “Behold, the Judge is standing at the doors” (James 5:8-9). Keep awake, then … if he comes suddenly, he must not find you asleep.

He came among us once as a stranger, and we put him on a cross. He comes among us now, in the guise of the stranger at the door. He will come in the future, not as a stranger, but as the King in his glory, and “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow” (Phil. 2:10). “The coming of the Lord is at hand,” says Saint James. “Behold, the Judge is standing at the doors” (James 5:8-9). Keep awake, then … if he comes suddenly, he must not find you asleep.

Amazing grace: “Wesley, the Evangelist, was a man possessed of amazing grace. Never did he lose his temper; and always was he prepared to endure a blow, if the dealing of it would relieve the hysteria of his assailant. Repeatedly, when struck by a stone or cudgel, he quietly wiped away the blood and went on preaching without so much as a frown on his face. He loved his enemies; and do what they would, they could not make him discourteous or angry. … In danger, Wesley had taught his followers to think of the Christ before Pilate, of the Son of God before a raging, crucifying mob. Thus it was, that Wesley’s serenity first broke, and later won, the heart of many a mob-leader and ruthless enemy – thus it was, too, that many a one-time brute came to be transformed into a gentle, saintly class-leader and understanding shepherd of souls.”

Amazing grace: “Wesley, the Evangelist, was a man possessed of amazing grace. Never did he lose his temper; and always was he prepared to endure a blow, if the dealing of it would relieve the hysteria of his assailant. Repeatedly, when struck by a stone or cudgel, he quietly wiped away the blood and went on preaching without so much as a frown on his face. He loved his enemies; and do what they would, they could not make him discourteous or angry. … In danger, Wesley had taught his followers to think of the Christ before Pilate, of the Son of God before a raging, crucifying mob. Thus it was, that Wesley’s serenity first broke, and later won, the heart of many a mob-leader and ruthless enemy – thus it was, too, that many a one-time brute came to be transformed into a gentle, saintly class-leader and understanding shepherd of souls.”

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.

This is not just an outdated idea from a bygone era, but an idea whose time has come once again. We need this integration if the church is going to survive the chaos and complexity of the 21st century. The recovery of tradition and innovation among this generation is a sign of renewal, a Spirit-inspired movement that should give us hope for the future of the church as it rediscovers its ancient roots. The integration of tradition and innovation is found at the intersection of faith, formation, and mission for today.