by Steve | Apr 14, 2022 | In the News

By Steve Beard

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.

“On a hill far away, stood an old rugged cross,” we sang. “The emblem of suffering and shame / And I love that old cross where the Dearest and Best / For a world of lost sinners was slain.”

Modern day hipsters may roll their eyes at the sentimental lyrics, but they stuck with me. It was a sing-a-long song about the most brutal injustice in human history and it became a well-known gospel chorus for an entire generation. Johnny Cash recorded four different versions. It was also recorded by Al Green, Ella Fitzgerald, Merle Haggard, Mahalia Jackson, Patsy Cline, Willie Nelson, and Loretta Lynn.

“The Old Rugged Cross” was written in 1913 by a Methodist preacher named George Bennard (1873-1958) who was converted to faith as a young man after walking five miles to a Salvation Army meeting. At age 15, he had lost his father in a mining accident. Bennard found new life and inspiration in giving his heart to a Savior riddled with nail scars who had conquered death.

“The crucifixion is the touchstone of Christian authenticity, the unique feature by which everything else, including the resurrection, is given its true significance,” writes the Rev. Fleming Rutledge in her magisterial book, The Crucifixion. “Without the cross at the center of the Christian proclamation, the Jesus story can be treated as just another story about a charismatic spiritual figure. It is the crucifixion that marks out Christianity as something definitively different in the history of religion. It is in the crucifixion that the nature of God is truly revealed. Since the resurrection is God’s mighty trans-historical “Yes” to the historically crucified Son, we can assert that the crucifixion is the most important historical event that has ever happened.”

When my father would serve communion at our United Methodist church, he said: “The body of Christ, broken for you. Feed on him in your heart by faith with thanksgiving.” Those words can still bring tears to my eyes. Sundays come and Sundays go, but those words stick in my soul. The Lamb of God was betrayed by a sleazy friend, ambushed by a well-armed battalion, falsely accused by conniving religious leaders, condemned by a spineless politician, and publicly executed before his weeping mother as cries of ridicule filled the air and birds of prey circled overhead.

To the abused who feels shame, this Crucified Christ stands with empathy. To the wrongly accused, this Crucified Christ stands with the truth. To all those victimized by injustice, this Crucified Christ stands with the innocent. “Come to me, all you who are weary … and I will give you rest,” Jesus said.

There are countless examples of contemporary Christian leaders who fail to live up to the Jesus ideal. Unfortunately, that has been the failed track record of Church history. But the Christ who was humiliated and shivved in the side on Golgotha is the genuine article. I try to keep my eyes on him. In every conceivable way, Jesus is counterintuitive. Who would have ever come up with a game plan of forgiving your enemies, turning the other cheek, and loving those who plot your demise?

“Even the excruciating pain could not silence his repeated entreaties: ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’ The soldiers gambled for his clothes,” wrote the late Anglican scholar, the Rev. Dr. John R.W. Stott. “Meanwhile, the rulers sneered at him, shouting: ‘He saved others, but he can’t save himself!’ Their words, spoken as an insult, were the literal truth. He could not save himself and others simultaneously. He chose to sacrifice himself in order to save the world.”

I understand the reluctance to spend inordinate time dwelling on the sufferings of Christ. It’s macabre and grotesque. It is the stigma of the story, the stain, the moment you turn your head away. But it is an inescapable part of redemption’s drama.

For those in the modern era, it is hard to imagine a time when crosses weren’t sold as bedazzled necklaces, home décor accessories, or garish t-shirt designs (“Body Piercing Saved My Life”). The cross was not always viewed as an icon for a faith dedicated to a kingdom that was not of this world.

“To the early Christians it was a symbol of disgrace. They could not look upon it as an object of reverence,” wrote historian George Willard Benson. “Death by crucifixion was the most shameful and ignominious that could be devised. That Christ should have been put to death, as were debased and despised criminals, was bitterly humiliating to his followers.”

Over the centuries since Christ’s blood-soaked public execution, the cross was slowly transformed from a symbol of shame and humiliation to one of victory and triumph for all of us who have been shamed and humiliated.

In his critically acclaimed book, Dominion: How The Christian Revolution Remade the World, British scholar Tom Holland points out that the tales of a human-divine hybrid were not unfamiliar in ancient history. Mythology from Egypt and Greece and Rome featured heroic monster-slayers and a pantheon of warlords that claimed to be empowered from the heavens.

“Divinity, then, was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings,” writes Holland. “Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque.”

The gospel is upside-down storytelling. Perhaps it helps explain the inexplicable allure of Jesus. The story does not end on a towering cross on the edge of town where the dying moan and mothers weep. More was to unfold.

Osiris, Zeus, and Odin are worshipped no longer. The Savior of the widow and orphan and tax collector is still worshipped around the globe. That is not chest-puffing triumphalism; it is simple reality.

“The crucifixion of Jesus, to all those many millions who worship him as the Son of the Lord God, the Creator of heaven and earth, was not merely an event in history, but the very pivot around which the cosmos turns,” writes Holland.

Holland only returned to the church of his childhood while writing his book. His thinking was dramatically affected while filming near a battlefront in an Iraqi town where Islamic State fighters had previously used crucifixion as a means of terror. “For the first time, I was facing the reality of crucifixion as it had been practiced by the Romans, face to face,” he told the Church Times. “It was physical in the air … people had been crucified by people who wanted the effect of crucifixions to be that which the Romans had wanted. They wanted to generate the sense of dread and terror and intimidation deep in the gut, and I felt that….

“I realized how important it was to me to believe that, in some way, someone being tortured on the cross illustrated the truth of the possibility that power might be vanquished by powerlessness, and that the weak might vanquish the strong, and that … hope might be found in the teeth of life in despair.”

Perhaps the hope found in the horror of the cross of Christ is the “assertion that the same God who made the world lived in the world and passed through the grave and gate of death,” wrote novelist Dorothy Sayer. Explain that to an unbeliever, and “they may not believe it; but at least they may realize that here is something that a man might be glad to believe.”

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. This article originally appeared in Good News in 2020. Artwork: “Station of the Cross: Fall” by Ostap Lozynsky of Lviv, Ukraine. Special thanks to iconart-gallery.com.

by Steve | Apr 8, 2022 | Front Page News

By Thomas Lambrecht

Methodism on the continent of Africa continues to flourish – countering the decline in North America. At the same time, traditionalist African leaders report that there have been some incidents of punitive action by hostile bishops.

In a recent troubling situation, yet another African bishop is persecuting pastors and leaders because of their connection with traditionalist views and organizations. This continues a pattern noted in 2020 in Central Congo and North Katanga episcopal areas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In those earlier cases, leading pastors were removed from their appointment and in some cases unjustly suspended without any complaints being filed or opportunity to defend themselves with a due process.

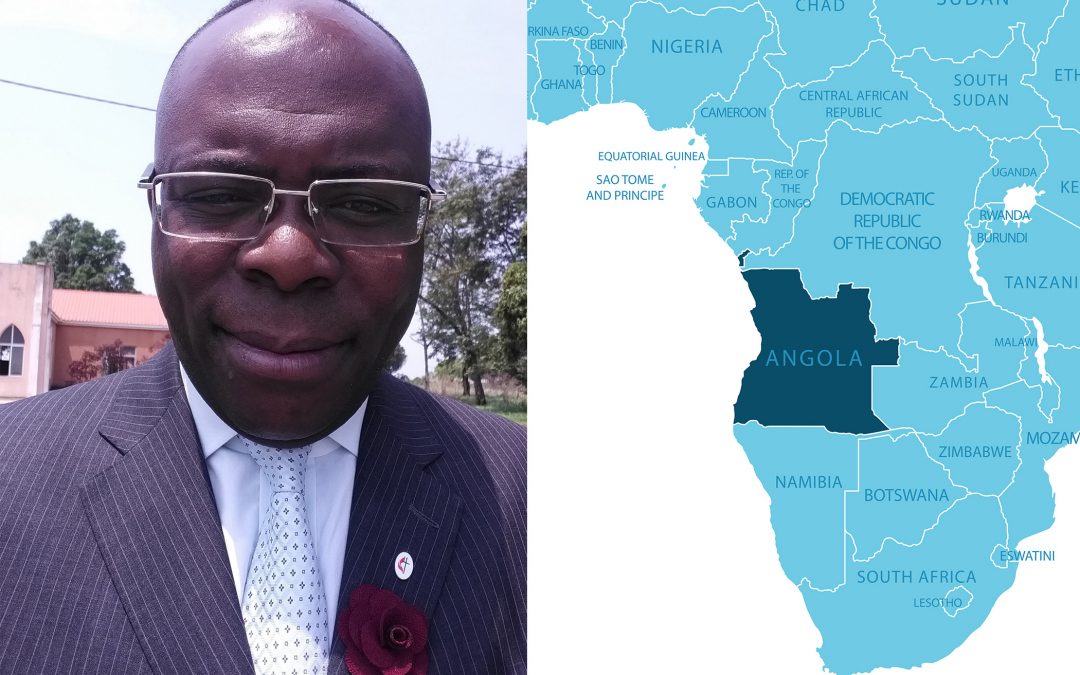

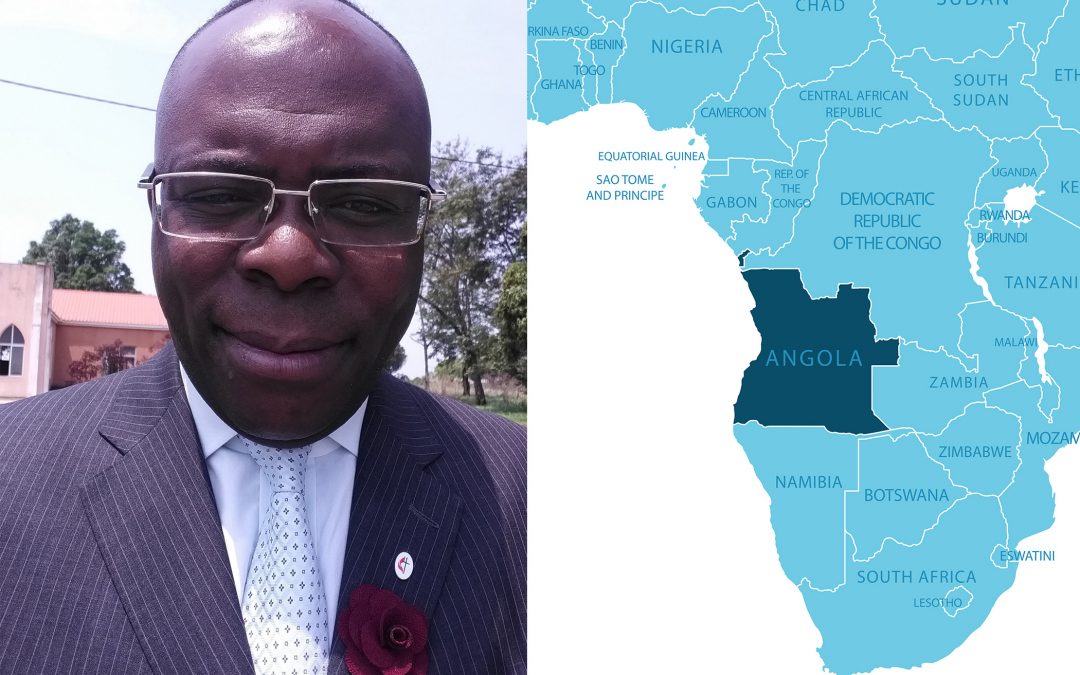

Now, on February 24, 2022, Bishop José Quipungo of East Angola expelled the Rev. Bartolomeu Dias Sapalo from The United Methodist Church under the charge of “treason.” (There is no such chargeable offense in the UM Book of Discipline.) In addition, Quipungo removed Sapalo from his position as Dean of Quessua Faculty of Theology and as pastor in charge of Nova Galileia United Methodist Church. He was given ten days to remove all his belongings and vacate the official faculty residence and told to “get out of Quessua Mission immediately.”

Bishop Quipungo gave as the reason for this action that Sapalo was “involved with the Separatist Movement (Global Methodist) under the leadership of Mr. Jerry Kullah (sic) and after having previously been advised not [to] be aligned with them (‘GMC’).” (It should be noted that Sapalo is not aligned with the “GMC” because that denomination is not yet in existence.)

Sapalo reported, “The bishop received the document entitled ‘Africa Initiative’s Position Statement on Holding 2022 General Conference.’ On this document, my name is included as an executive member [of the African Initiative]. There is no stipulation in the Discipline against participation in the Africa Initiative. Yet, this was the sufficient reason, in his opinion, to call me and then send me a letter of expulsion. There was, however, no church trial at all.”

Under the Book of Discipline, before a clergy member can be removed, a formal complaint must be filed. An investigation must take place, along with attempts to resolve the complaint through mutual agreement. If no agreement can be reached, the clergy person is entitled to a trial, at which the church must prove its charges and a jury of other clergy can decide to acquit or convict the defendant. The charged clergy person is also entitled to have an advocate to help defend them in this process. At the trial, it is the jury (not the bishop) that decides what the penalty for a guilty verdict would be. The defendant is further entitled to appeal the verdict if there were errors made in the church trial.

In Sapalo’s case, none of these procedures were followed. He was summarily fired from his church positions and removed from membership in The United Methodist Church by the bishop alone.

When asked about the possibility of an appeal, Sapalo said, “There is no recourse in this matter because at the local level the Jurisdictional Committee on Episcopacy is non-functional. There are [also] conflicts of interest in play. For example, the [chair] of the Conference Board of Ordained Ministry is [the bishop’s] nephew. His administrative assistant is another nephew, and other key positions in the church are occupied by his close relatives. There is simply insufficient accountability at the level of the annual conference.”

Another element playing into Sapalo’s dismissal was the jockeying for position in upcoming elections to be the bishop to replace Quipungo. Such elections were originally scheduled for 2020 at the Africa Central Conference. Due to Covid postponements, they are now scheduled for 2024 (unless Judicial Council rules they may be held earlier). Quipungo had reached the mandatory retirement age of 68 in 2016, but avoided retirement through procedural steps. He is now age 75, yet continuing to serve as bishop.

The 2020 East Angola Annual Conference endorsed candidates for the episcopacy. Sapalo was the top candidate endorsed by the conference, and his wife, Rev. Suzana Luisa Lourenҫo Sapalo, was the second endorsed candidate. According to Sapalo, the third and fourth endorsed candidates (who received half the number of votes Sapalo received) are close relatives (a nephew and a grandson) of Bishop Quipungo and members of his same tribe. Expelling Sapalo would make him ineligible to be elected bishop, opening the way for one of Quipungo’s relatives to be elected.

As Sapalo reports, “It is hard for Americans to understand what the systems of authority are like in Africa. For example, pastors or laypersons who try to contradict a bishop can face serious punishment. He threatens them with expulsion. The situation in Angola East is illustrative of a larger problem. District Superintendents are suspended or kicked out, conference staff persons are suspended, pastors are punitively moved from one church to another and sometimes are not given appointments, and cabinet members are not consulted prior to any decision regarding church business. At least five other clergy members have been expelled in East Angola.”

Furthermore, Sapalo alleges Quipungo lacked transparency in administration. “For the past 22 years of his episcopal ministry, we never heard in any ordinary meetings or at Annual Conference session any report on how he uses the funds received from donations, from UMC Agencies, or even from the Government; he has not been accountable.”

For now, Sapalo is unemployed and, as he puts it, “stranded.” “Unfortunately, I cannot attend any United Methodist congregation right now. I now live at my older brother’s house here in Luand, 400 kilometers [250 miles] from where I was engaged in pastoral ministry. I left my wife behind, but she is also pressured to vacate the house, though she is also a pastor. Right now, I am looking for a job as a taxi driver to support my children with school fees and other basic expenses.”

It is difficult to fathom the hardships of ministry and service to the church in Africa to begin with – difficulties in travel, diseases, lack of the best health care, and lack of adequate income. Add to that the dictatorial style of some bishops and their unjust abuse of power against some who are just trying to be a faithful voice for Wesleyan doctrine. Our brothers and sisters are making sacrifices for the cause of Christ that we cannot comprehend.

One of the key premises of the Global Methodist Church is that there must be accountability at all levels of the church, from the lay members all the way to the bishops. We need a radically different approach to power and authority in the church. Jesus said, “You know that those who are regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be slave of all. For the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:42-45).

I can attest that the leaders of the Global Methodist Church exhibit this kind of leadership humility. The Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline of the GM Church contains a straightforward accountability process for all, including bishops. The fair processes of the church must be followed. Without them, there is an abuse of power. Some of our best leaders have suffered such abuse, both in Africa and in parts of the U.S. It is time for the abuse to end.

The current UM system generally does not allow for bishops to be held accountable. Such accountability is at the whim of other bishops. Increasingly, bishops are unwilling to “interfere” with how other bishops administer their own episcopal area. This lack of accountability and the resulting abuse of power is one of the major reasons for separation in the UM Church.

It is time for United Methodist leaders to renounce their punitive and coercive approach to leadership and allow traditionalists a gracious exit, so that we may all serve the cause of Christ without hindrance in the way we are led to do so.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Reporting for this article also came through Dr. David Watson, dean of United Theological Seminary, Dayton, Ohio. Photo (left) is from Bartolomeu Dias Sapalo and (right) Shutterstock.

by Steve | Apr 2, 2022 | Front Page News

By Thomas Lambrecht

In the aftermath of the postponement of General Conference until 2024, there is understandably an explosion of interest by local churches in how to withdraw from The United Methodist Church and unite with the Global Methodist Church. As reported in a previous Perspective, this process of decision-making for local churches may take time (several months, up to a year or two). Congregations will act when ready, but it will also take the approval of their annual conference, which may only meet once a year, thus delaying the effective date of realignment.

Because General Conference has not yet adopted the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation, there is no unified plan of separation for local churches to follow. What will be required in each annual conference will be different. Good News has appealed to bishops and annual conference leaders to take a gracious and amicable approach toward separation, rather than a punitive one.

Some bishops have said that they will do all they can to help local churches move to where they want to be, whether that is remaining United Methodist or aligning with the Global Methodist Church. They have promised not to put obstacles in the way of churches and pastors who want to realign to the GM Church. A few bishops have indicated a willingness to use ¶ 2548.2 to allow congregations to change affiliation and to work with churches to reduce the financial demands for departure.

As mentioned in that previous Perspective, one option for reducing financial demands, even using ¶ 2553, is to allow the payment of pension liability through use of a promissory note, rather than an upfront cash payment. As the plan sponsor, an annual conference can work with Wespath to make this solution work, so that the liability of future pension payments is covered, no pastor’s pension would suffer because of separation, and that the local church would have an affordable route to realignment.

Other bishops and annual conferences, however, seem determined to try to prevent local churches from moving to the Global Methodist Church with their property and assets. In addition to the already high financial cost of withdrawal under ¶ 2553, some conferences and bishops are requiring repayment of previous grants made to the local church and even a percentage of the church’s appraised property value – anywhere from 20 to 50 percent! This would force a congregation to essentially pay twice for a facility that they already paid to erect and maintain. In most cases, the annual conference put no money into constructing that church building, but will in these instances reap a windfall as the church departs (if it is even able to afford such a departure). Even some bishops who signed the Protocol are now backing off from its principles in order to support onerous financial requirements.

What are the ramifications of such an approach?

Annual Conference Withdrawal

One unintended consequence of a failure for General Conference to meet and pass the Protocol is that annual conferences may be able to depart from the UM Church more easily than if the Protocol had passed. Judicial Council is expected to issue a ruling by mid-May on whether an annual conference can vote to withdraw. In a previous decision, the Judicial Council has stated, “The annual conference … exercises autonomous control over [its] agenda, business, discussion, and vote on the question of withdrawal” (Judicial Council Decision #1366 on page 44).

If the Judicial Council rules in line with its previous decision, the annual conference (in the absence of any other legislation passed by General Conference) could determine to withdraw from the UM Church and align with the GM Church by a simple majority vote. The Protocol, on the other hand, would require a 57 percent vote to do so. This would make it likely that more annual conferences would withdraw before the 2024 General Conference than wait for the Protocol to pass in 2024.

Weakened Local Churches

Annual conferences that impose high financial costs on departing congregations will weaken those congregations that can afford to disaffiliate under those terms. Hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of dollars that could have been used to support the ministry of that local church will now support the bureaucracy of a liberal annual conference. Congregations will have to tap out their financial reserves, cut back on ministry programs and staff, and/or borrow heavily (paying costs for interest on indebtedness) in order to align with a denomination that reflects their theological and missional identity. Some congregations taking this route might not even survive. Other congregations will suffer a heavy financial burden that could hamper their ministry in the community for years. The serious financial costs jeopardize the ability of all these congregations to have a strong start in a new denomination.

These onerous financial demands would do harm to these congregations – contravening Wesley’s dictum to “do no harm” that is often cited by centrists and progressives as one of their guiding lights. What annual conferences might gain to help ensure their institutional status quo could severely compromise the ability of departing congregations to continue strong ministry in their local communities.

Hostage Congregations

The more likely alternative is that congregations faced with insurmountable financial costs of realignment will simply be stuck in a United Methodist denomination that is rapidly leaving them theologically. With these financial demands, the annual conference is essentially holding the church hostage, forcing them to remain within a church in which they no longer fit.

Such a situation is not good for the local church, nor is it good for the annual conference. Obviously, the local church that is begrudgingly still United Methodist is not going to wholeheartedly support its annual conference’s mission and purpose. It may not willingly support financially an annual conference that would treat its congregations with such disrespect. The annual conference may get less money out of the congregation than if it just allowed the church to leave with paying two years’ apportionments and no property payment.

Traditionalist members of that reluctantly remaining congregation may decide they do not need to be part of a congregation held in a denomination against its will. They may decide to drive down the road to another (probably non-denominational) congregation and be lost to Methodism. The remaining congregation will grow weaker with the loss of members, again compromising its ability to offer vibrant ministry in that local community. The vicious circle of members leaving, reduced ministry, and more members leaving could ultimately lead to the demise of that congregation.

How does it serve the interests of the annual conference to force congregations to remain in the annual conference against their will and potentially cause the congregation to close? First, from a progressive perspective, it would disempower and eventually get rid of annoying traditionalists and their “old-fashioned” understanding of the faith that is getting in the way of real progress toward an inclusive progressive church (without losing that congregation’s valuable property). Second, it would allow the annual conference to send liberal pastors to serve that congregation and hopefully change the character of the church to being a progressive one by replacing departing traditionalists with new, more progressive members. Worst case, if the church closes, the annual conference could at least sell the property and use the proceeds to fund progressive ministry in the years ahead.

This warped perspective of the Kingdom of God prioritizes progressive ideology over living by the Golden Rule. It treats traditionalists in a way that no progressive or centrist would want to be treated. It reflects a power play that cynically capitalizes on the fact that centrist/progressive bishops and annual conferences hold most of the power and can treat congregations unjustly with impunity. The only thing that might restrain them is a moral compass that remembers Jesus’ dictum that Christians are called to serve one another, not lord it over one another.

Blocked Progressive Agenda

Another consequence of attempting to hold traditionalists in the UM Church against our will is the potential that centrists and progressives might find their agenda for the church is blocked. Right now, the number one legislative priority of centrists and progressives is adopting a plan to regionalize church government. Their goal is to enable the U.S. part of the church to govern itself without interference from the new African majority.

However, plans to regionalize church government involves amending the church’s constitution, which will require a two-thirds vote at General Conference and a two-thirds vote of all the annual conference members around the world. If traditionalists in the U.S. and particularly in Africa are not allowed to withdraw, there will be more than enough votes to block any attempt to regionalize, thus defeating the centrist/progressive agenda.

I have never understood the centrists’ and progressives’ feverish attempts to keep the African churches part of the UM denomination, when the Africans alone could scuttle their legislative priorities. African delegates are much more informed than in the past and much more willing to have their own opinions and resist the dictates of bishops who go against the interests of faithfulness to traditionalist understandings of the faith. Despite hardball efforts by some liberal African bishops to muzzle traditionalist African leaders, African delegates are prepared to stand on their own in opposition to attempts to change the church’s teachings or marginalize African influence in the church.

The second legislative priority for centrists and progressives is to eliminate from the Discipline the traditional definition of marriage and allow the ordination of non-celibate LGBT persons to ministry. Yet, traditionalists still hold a narrow majority of the delegates to General Conference. Progressives pushed hard to elect progressive delegates to the 2020 General Conference and succeeded in making gains among clergy delegates. It is likely, however, that a 2024 General Conference will require new elections for a new delegation, and progressives might not be as successful. The number of U.S. delegates will decrease due to membership declines, and the number of African delegates will increase due to their membership growth.

It appears likely that if traditionalists are held in the UM Church by unaffordable financial requirements, there will still be a slim traditionalist majority at General Conference 2024. This is counterproductive to enacting the centrist and progressive agenda of “full inclusion” and U.S. autonomy. Thus, the quest for financial gain through intimidating traditionalist congregations into remaining United Methodist may turn out to be self-defeating for centrists and progressives.

Let the Conflict Continue

Ultimately, the worst consequence of forcing traditionalists to remain United Methodists against their will through onerous requirements is that it continues the conflict in the church. As long as a substantial group of traditionalists remains in the UM Church, there will be theological conflict. Previously, the goal has been to resolve the conflict, release and bless one another to pursue ministry in the way consistent with our divergent beliefs, and move forward in a positive direction. Bishops and annual conferences that impose unaffordable provisions on local churches wanting to realign are abandoning the opportunity to resolve the conflict and allow the church to move forward in a positive way. Instead, they would be placing short-term, primarily financial self-interest ahead of setting a positive future for the church.

Bishops and annual conferences in this moment have a choice. They can escalate the conflict with onerous requirements and attempt to block congregations from leaving The United Methodist Church. Or they can take a reasonable approach that facilitates the resolution of our church’s theological conflict for the sake of creating the opportunity for a positive future for all. For the sake of Christ’s Kingdom, it is to be hoped they choose the way leading to a positive future.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Mar 29, 2022 | Front Page News, Home Page Hero Slider

By Thomas Lambrecht

There was a popular song in the 1960’s, “What’s It All About, Alfie?” It asks the question, what is life and love all about? It was the theme song of the movie, Alfie, in which a wayward man is searching for meaning in life.

With the postponement of General Conference until 2024 and the announced launch of the Global Methodist Church on May 1, 2022, many people across The United Methodist Church are waking up to the reality of separation in our denomination. Hundreds of churches are applying for disaffiliation from the UM Church. Hundreds more are discerning whether their future lies in the GM Church. In the process, thousands of laypersons who have been in the dark about all the conflicts leading up to this point are asking, “What’s it all about?” Why are many churches leaving the UM Church? Why would our congregation consider leaving for the GM Church?

This article aims to give a succinct, but not exhaustive, summary of what is at stake.

Theological Crisis

Baked into the DNA of United Methodism since 1972 is the idea of theological pluralism – that there are many different understandings of the faith and nearly all understandings are welcome within United Methodism. From the time our denomination was founded, we have not had a coherent, unified understanding of our faith. Is Jesus without sin and error, or was he a flawed human being like the rest of us who somehow became a revered moral teacher? Was Jesus’ death on the cross necessary for our salvation, or was it an act of so-called “divine child abuse?” Did Jesus really rise bodily from the grave, or was his “resurrection” only a greater spiritual awareness on the part of his disciples?

From the beginning of our church in the 1960’s, many boards of ordained ministry have approved candidates for ordination who believed and taught very diverse understandings of the faith. Beneath headline-grabbing issues such as marriage and sexuality, root theological issues have divided United Methodists for decades revolving around evangelism, church planting, the Great Commission, Sunday school curriculum, and even the most fundamental beliefs of the Christian faith. Those moving into the GM Church believe clergy (and indeed all Christians) should be able to recite the Apostles’ Creed without holding crossed fingers behind our back or reinterpreting the words to mean something other than what they say.

One way this doctrinal pluralism manifests itself is through disagreements over the understanding and interpretation of Scripture. Is the Bible “the true rule and guide for faith and practice” we say it is in our doctrinal standards (Confession of Faith, Article IV)? The United Methodist Church affirms, “Whatever is not revealed in or established by the Holy Scriptures is not to be made an article of faith nor is it to be taught as essential to salvation” (Ibid). Yet, many bishops, clergy, and UM leaders, for example, want to rewrite the biblical understanding of marriage taught in Scripture (e.g., Matthew 19:2-9) and ignore or countermand the explicit teaching of Scripture that same-sex relationships are not in keeping with God’s design for human relationships (e.g., Romans 1:21-27; I Corinthians 6:9-11). Some high-profile United Methodist leaders would go so far as to relegate whole chunks of the Bible to the category of “they never reflected God’s timeless will.”

This disregard for the clear teaching of Scripture undermines its authority. If the Bible can be wrong about one important aspect of Christian theology, can it be wrong about other aspects of faith? The Bible should be our authority for what to believe, not what aspects of Scripture we accept as God’s self-revelation and what aspects we ignore. In the latter case, we become the authority for our own faith. But that approach contradicts what we say we believe as United Methodists. We would no longer be true to our Wesleyan understanding.

The theological crisis manifests itself most clearly right now in attempts to officially contradict Scripture by affirming same-sex relationships. We don’t vote at General Conference on the deity of Jesus or whether God performs miracles. But that crisis also manifests itself every time a pastor preaches an Easter sermon without reference to the resurrection or communicates that the way to salvation is “doing all the good you can” apart from Jesus’ atoning death on the cross.

For decades, our denomination has been able to muddle through despite all these theological differences. What has cast the church into an existential turning point now is the second crisis, an ecclesiastical crisis.

Ecclesiastical Crisis

The short description of our ecclesiastical crisis is that The United Methodist Church has now become unable to function by the processes and rules set by our church constitution. Over the years, bishops and other leaders who disagreed with the church’s teachings have increasingly turned a blind eye to violations of that teaching. The unwillingness to hold one another accountable to the teachings and practices of the church is the acid that has eaten away the foundation of our denomination.

In 2002, then-Bishop Joseph Sprague published a book, Affirmations of a Dissenter, that reinterpreted or denied many of the main tenets of Christianity. A complaint was filed against him for “dissemination of doctrines contrary to the established standards of doctrine of The United Methodist Church.” Those in charge of adjudicating that complaint took no disciplinary action against Sprague. Apparently, his beliefs were within the pluralistic realm of United Methodist faith.

Over the last 20 years, the accountability processes for clergy and bishops have broken down. Bishops have decided to circumvent the process by “resolving” complaints with little or no discipline for clergy who violate our church’s requirements. By the same token, complaints against bishops are “resolved” with no accountability by those bishops and church leaders entrusted with upholding the church’s Discipline. Bishops and leaders are only willing to enforce those provisions they agree with.

In 2016, the denomination appeared ready to unravel at General Conference. As a last-ditch effort to preserve unity, General Conference authorized a Commission on the Way Forward to figure out a solution and bring it to a special 3-day General Conference to be held in 2019. Contrary to the wishes and lobbying of many U.S. bishops, the 2019 General Conference reaffirmed once again the church’s historic stance on the definition of marriage and the ordination of non-celibate gays and lesbians. It further added accountability provisions to ensure that the church’s clergy and bishops would abide by the church’s teachings.

In response, many U.S. bishops and annual conferences publicly apologized for the conference’s decision and sought to distance themselves from it. More than half the U.S. annual conferences passed resolutions repudiating the decision of General Conference, with at least 11 saying they would not abide by it. Several annual conferences in spring 2019 ordained persons as clergy who did not meet the denomination’s qualifications. One European central conference removed the church’s teachings from its Social Principles. Another European annual conference and the whole U.S. Western Jurisdiction began looking into the possibility of separating from the UM Church because they disagreed with the General Conference stance.

Faced with this widespread rebellion against church teaching in parts of the U.S. and Western Europe, a group of bishops and church leaders representing traditionalist, centrist, and progressive theological perspectives agreed to a proposal for amicable separation. Called the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation, this proposal provided a clear and amicable way for traditionalist congregations and clergy to leave the UM Church, allowing the church to then change its teaching to accommodate a progressive understanding. (For more analysis on why traditionalists are willing to be the ones to move to a new church, despite the current Discipline upholding a traditionalist position, see this article.)

The Protocol was poised to pass at the May 2020 General Conference. With the pandemic causing the postponement of General Conference, finally now until 2024, progressives became increasingly impatient to move the church in a progressive direction. Several annual conferences adopted vision statements that stated they would now start “living into” the future they envisioned, despite the fact that the provisions in the Discipline remain unchanged.

Some individual bishops began taking punitive actions against traditionalist clergy, removing them from their appointments and in some cases even expelling them from the denomination without due process or trial. None of these bishops has been held accountable for their actions. There are bishops now who are openly stating that the General Conference (the only body empowered by our church constitution to make decisions for the whole denomination) can no longer adequately govern the church.

We have evolved to the point in our denomination that the actions and decisions of General Conference can be ignored with impunity by bishops and annual conferences that disagree. Bishops have become a law unto themselves within their own annual conferences, not subject to accountability to other bishops or the broader church. Decisions of the Judicial Council can be ignored. The third postponement of General Conference indicates that the power of institutional preservation of the status quo is greater than the inclination to move into a healthier future. Many progressives and centrists seem increasingly uninterested in an amicable way to allow separation to occur. Instead, many seem to want to punish traditionalists for holding the beliefs that we have and at the same time doing whatever they can to delay or prevent traditionalist clergy and churches from separating from the UM Church in order to join a GM Church that more faithfully represents our faith perspective.

End Game

Where does this leave us, besides in a mess? Given the theological and ecclesiastical dysfunction of the church, many traditionalists are no longer able to wait for General Conference to pass the Protocol. The longer the delay, the less likely its adoption becomes. Meanwhile, theologically conservative church members are leaving our churches and clergy are retiring or leaving the church. Hundreds of churches have requested disaffiliation from the UM Church this year, with hundreds more contemplating that possibility over the next 24 months, even before General Conference meets.

To accommodate this groundswell of departures and to prevent the loss of these congregations to Methodism, the Global Methodist Church has announced it will launch on May 1 of this year. As last week’s Perspective explained, there are ways for a church to move to the GM Church with its property and assets intact. In some annual conferences, the way may be prohibitively expensive, but it is still possible.

Hopefully, the narrative in this article helps explain why many churches are willing to do what they must in order to separate from the UM Church.

|

|

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News

|

|

by Steve | Mar 18, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

The third postponement of General Conference until 2024 and the announced launch of the Global Methodist Church on May 1, 2022, have set off a storm of interest and controversy. Faced with the reality that a new denomination is moving forward without the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation, many questions answered by the Protocol are now uncertain.

Some individuals and churches are almost in panic mode, thinking that they have to make a decision right now (or at least by May 1). Others are just waking up to the fact that separation is taking place in the UM Church.

Important Timeline Considerations

First, it is important to understand that the launching of the Global Methodist Church on May 1 is just the starting point for that new denomination, not a deadline. Beginning May 1, the GM Church will be able to receive congregations, clergy, and annual conferences into its membership. There is no deadline for a congregation, clergy person, or annual conference to join the GM Church. It will be open to receiving members and churches from other denominations whenever they want to join, with no endpoint.

There are some local churches that have already withdrawn from the UM Church that will be positioned to join the GM Church on May 1. There may also be non-UM churches of a Wesleyan heritage who are also able to join on May 1. The vast majority of churches will take time over the next few years to move into the GM Church.

We understand that there are probably more than 100 churches across the U.S. that have already requested disaffiliation so far in 2022. These churches have been moving through a disaffiliation process guided by ¶ 2553 in the Discipline that requires apportionment and pension liability payments. These churches will need to have their disaffiliation approved by their annual conference meeting in May or June. They will not move into the GM Church until they receive that annual conference approval.

Now that the door is open to join the GM Church after May 1, there will be hundreds more local churches that will apply for disaffiliation over the next year. They will also have to move through the disaffiliation process set by their annual conference and bishop. This will again require approval by their annual conference, either at a special session called sometime near the end of 2022 or at their regular session in spring of 2023 (for the U.S. – the time frame for churches outside the U.S. may be different). Thus, this wave of churches would not be able to join the GM Church until the end of 2022 or the middle of 2023.

Then, as things develop for the GM Church and the UM Church has a chance to further define itself, there will be other congregations down the road that make the decision to move into the GM Church. It is important to note that the provisions of ¶ 2553 expire at the end of 2023, meaning that churches withdrawing under that paragraph need to do so before their annual conference session in 2023. However, there are other avenues in the Discipline that allow local churches to move to the GM Church (see below).

The bottom line is that there is no need to panic or make a rushed decision. Churches can take the time they need to evaluate their situation and the options available to them and make a prayerful, well-considered decision about their future. The doorway into the GM Church will always be open!

¶ 2553 Vs. ¶ 2548.2

There are two main ways that churches can disaffiliate from the UM Church and move into the GM Church: ¶ 2553 that was adopted at the 2019 special General Conference and ¶ 2548.2 that has been in the Discipline since 1948. What is the difference between the two?

¶ 2553 was adopted in 2019 as a way for churches that disagree with the denomination’s position on LGBT ordination or same-sex marriage (or with their annual conference’s response to the denomination’s position) to withdraw from the UM Church. The focus here is on withdrawing to become an independent congregation, after which the church might decide to align with a different denomination, such as the GM Church. Almost all the churches that have withdrawn under ¶ 2553 have become independent and not aligned with another denomination (so far).

¶ 2553 requires that the departing congregation pay two years’ apportionments and the total amount of its unfunded pension liability to the annual conference before departing. Approval for withdrawal requires a two-thirds vote of the church members voting at a church conference, the conference board of trustees, and a majority vote of the annual conference. The local church would then be able to keep its property, assets, and liabilities as it continues forward as an independent congregation or decides to align with another denomination.

¶ 2548.2 was originally adopted in 1948 to facilitate the transfer to other denominations of church facilities that no longer were able to serve a changing community by remaining United Methodist. The paragraph allows the annual conference to transfer (“deed”) the church’s property to a denomination represented in the Pan-Methodist Commission (five African-American Methodist denominations) or “another evangelical denomination.” Instead of moving into an independent status, the congregation would move from the UM Church directly into the GM Church.

¶ 2548.2 does not require specific monetary payments. Other paragraphs in the Discipline require the congregation’s share of unfunded pension liabilities be cared for. Wespath has expressed openness to these liabilities being covered by a promissory note secured by a lien on the church’s assets, rather than an upfront payment in full (see below). This approach would relieve one of the major financial barriers to especially smaller local churches wanting to move to the GM Church, but it requires annual conference approval of this approach. ¶ 2548.2 does not specify a threshold for local church approval of this transfer, so it could allow a simple majority vote by the church’s members. The transfer requires approval by the bishop, the district superintendents, the district board of church location and building, and the annual conference. The local church’s property, assets, and liabilities would be transferred to the GM Church, which would then release them to the local congregation because the GM Church has no trust clause.

Some annual conferences have put additional requirements on the disaffiliation process under ¶ 2553 (and could under ¶ 2548.2), such as an extended discernment period for the local church or payment of a percentage of the church’s property value. Some annual conferences at their upcoming sessions will be considering proposed policies that would govern the terms of local church disaffiliation under ¶¶ 2553 or 2548.2.

In the interest for an amicable resolution of our denominational division, the use of a promissory note for pension liabilities and the elimination of extra financial terms (additional apportionments, percentage of property value) would help by not placing undue hurdles in the way of local churches that want to move to the GM Church. With a vision for maintaining a heart of peace, it should be as easy and fair as possible for churches to move to where they want to be. Congregations should not feel as though they are being coerced into remaining United Methodist.

What about Pension liability?

In my Perspective two weeks ago, I wrote, “[¶ 2548.2] allows pension liabilities to be transferred to the local church or to the other evangelical denomination.” In another place, I stated, “a local church can carry its pension liability with it” into the GM Church. I need to clarify those statements, and in one respect, I was incorrect.

There are two ways that a church’s share of its annual conference’s unfunded pension liability (an amount roughly 4-7 times their annual apportionment) could be cared for. One way is an upfront cash payment by the church to the annual conference. Churches either would have to raise the money to make the payment or, in some instances, may be able to borrow that money as secured by their property.

The other way to care for the pension liability would be for the church to enter into a promissory note in the amount of the liability, secured by a lien on the church’s property. There would only be payments on that note if the annual conference needed to make payments to Wespath to cover unfunded liabilities. (This would normally only happen in case of a severe economic downturn.) The advantage of this approach is there would be no large upfront payment that could price many churches out of the possibility of withdrawing. Payments would only be made when there was a need for the money to cover pensions, which happens very rarely. The annual conference, as the pension plan sponsor, would need to approve this approach.

The UM annual conference would still have the pension liability, and the withdrawing local church’s share of that pension liability would still be owed to the UM annual conference. But with the promissory note approach, the church would only pay money to the annual conference when it is needed. In a recent FAQ document, Wespath allowed this approach. “While paragraph 1504.23 mandates a pension withdrawal payment, it does not address the timing of the payment under all potential paths of separation…. [U]nder paragraph 2548.2, while the payment is due in full, the annual conference in its sole discretion, may agree to adjust the timing of the payment.”

As currently envisioned, the Global Methodist Church would not assume any responsibility for unfunded pension liability. It would attach only to each local church, which would only make payments when the funds are needed. (I apologize for this incorrect information.)

As people process the options available to them, we will be dealing with many more questions that arise. There is no reason to have all the answers immediately. Take the time to research the answers. View the Global Methodist Church website for much information (globalmethodist.org).

See these two recent articles:

The process for Congregations to join the Global Methodist Church

How clergy align with the Global Methodist Church

More articles from the GM Church will be forthcoming. Feel free to email us with your questions. Stay tuned for more informative articles in the future.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo from Shutterstock.