by Steve | Oct 14, 2022 | Uncategorized

By Scott Field

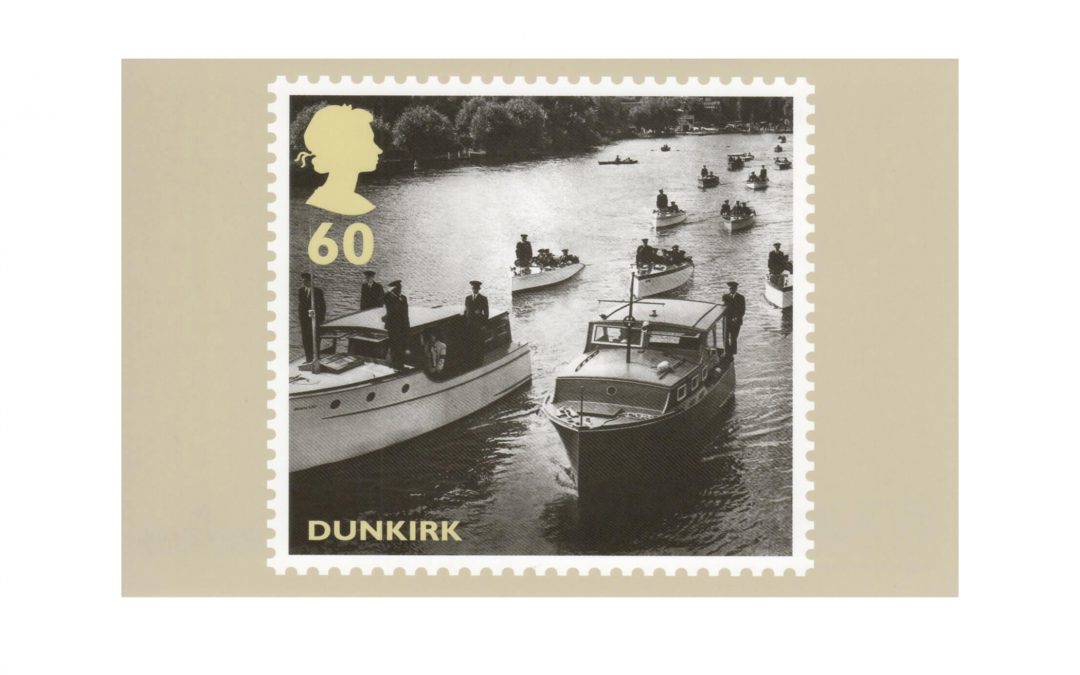

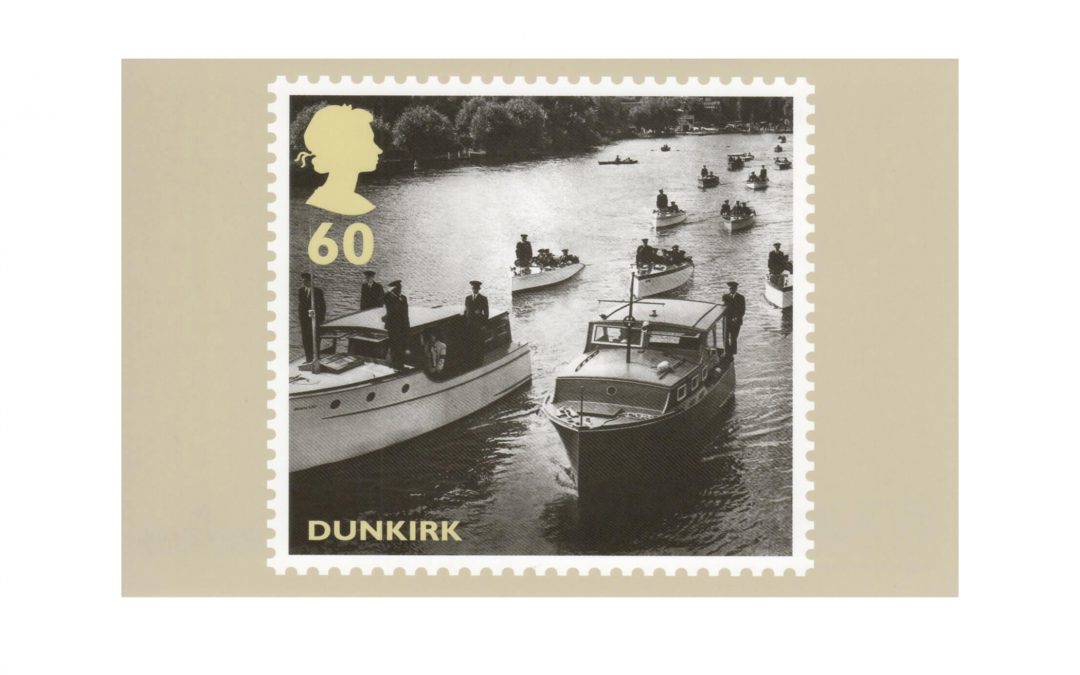

By the end of May 1940, Germany’s rapid advance through north-west Europe had pushed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), along with French and Belgian troops, back to the coast of the English Channel. Stranded on the beaches of the French port of Dunkirk, they faced certain capture, which would have meant the loss of Britain’s only trained troops and the collapse of the Allied cause. The Royal Navy hurriedly planned an emergency evacuation – Operation ‘Dynamo’ – to rescue the troops and get them to Britain.

To speed up the evacuation, an appeal went out to owners of pleasure boats and other small craft for help. Boats of all shapes and sizes cast off – 850 of them. These privately owned craft, the smallest of which was a 14’ fishing boat, became known as the “little ships.” The effort brought 338,000 soldiers – a third of them French – to safety in England between 27 May and 4 June. The evacuation, hailed as miraculous by the press and public, was a big boost for British morale. Losses at Dunkirk were still heavy, however. Winston Churchill pointed out at the time that great challenges remained, but the “little ships” response was a remarkable demonstration of resilience by the British people and for the British people. See photos here.

What do the “little ships” at Dunkirk have to do with United Methodists right now?

As I have been meeting with leadership teams from local congregations and responding to emails and phone calls from concerned United Methodists in our region and beyond, the risk-taking resilience of the Dunkirk “little ships” came to mind.

Allow me to clearly state three disqualifiers to what I am writing in this commentary:

- I do not want in the least to detract from the heroism of the actual participants in “Operation Dynamo.”

- My comparison here is an analogy at best; we are facing the denominational unraveling of United Methodism, not the literal threat of foreign military invasion.

- I want to highlight the resilience of local Methodists, akin to the courage of the British citizens who took matters into their own hands, in an unprecedented and challenging situation.

So, what about these resilient Methodists in their local churches?

If you listen to or read some of the progressive-leaning influencers within the United Methodist denomination, you might conclude that the Methodists seeking disaffiliation from the UM Church are narrow-minded, bigoted, uninformed, and under the sway of separatists who have been plotting a denominational revolution for decades. For progressives and liberationists, who normally assume institutions themselves are the source of so much oppression, entitled privilege, legacy discrimination, and the injustices plaguing the world, you would think they might also include United Methodism itself in their indictment of the “principalities and powers” that afflict us all, right?

Well, apparently not so much.

The folks in the High Tower, many of our UM leaders and administrators, seem to regard Methodists considering disaffiliation as an annoyance. We are gumming up the smoothly running machinery of United Methodism and the denomination will be much better off when we leave. In the meantime, while our denominational leaders themselves disregard the standards and accountability processes of the UM Book of Discipline in many cases, each congregation inquiring about the process of disaffiliation is informed with authoritative solemnity that they must follow the “letter of the law” when is comes to the requirements of Paragraph 2553. Though Jesus himself recommended seeking reconciliation, our denomination seems to prefer the alternative Jesus warned against, “And if that happens, you won’t be free again until you have paid the last penny” (Matthew 5:26; parallel in Luke 12:59). Many have suggested that for our leaders in The High Tower, it’s actually all about the money. Perhaps so.

Okay, but what about the resilient Methodists in their local churches?

I’m impressed with the laity taking the initiative in pursuit of a better future for their congregation.

- Local church administrative councils or boards have held congregational meetings to share information about the current denominational divide and have begun a process of discernment and, potentially, disaffiliation from the UM Church. One administrative team had to hold their information meeting in the local American Legion Hall because the pastor would not allow it to take place in the church building. A full house showed up at the Legion Hall regardless. Resilient Methodists.

- Others, recognizing that their church would probably not meet the required two-thirds majority vote to disaffiliate, are exploring the launch of “dinner church” or micro church meetings in their area, perhaps as satellite house-sized congregations connecting via livestream or recorded video with a larger Global Methodist Church elsewhere. They are resilient – willing to lean into a completely different model of church in order to cultivate their faith, experience Christian community, and share the transforming gospel of Christ with others.

- A group of members from seven UM churches geographically near each other are at work planning the establishment of a new Global Methodist Church initially comprised of themselves and other “wandering Methodists” in the area. They are planning to leave their “home churches” to form a new congregation together. Resilient Methodists.

- A congregation that describes itself as “small, rural, elderly, and on its last legs” has decided to continue providing free meals to the needy in their community. They hope the new Bishop arriving in January will leave them alone because they know they cannot sustain the financial costs of disaffiliation, are concerned that a new pastor might try to “convert them to progressivism,” are very happy with their current pastor’s biblical grounding, and presume they may close the church doors at the time of the next pastoral transition anyway. They are few, but they are stalwart in serving their community. Resilient Methodists.

In no way are these collectives of the narrow-minded, bigoted, and angry. They are warm-hearted and welcoming to all who are on a spiritual quest. They want to worship the Lord Jesus, offer the good news of salvation through faith in Christ, welcome any and all who are searching for redemptive community, and serve the needs of those nearby. These are resilient Methodists.

Three cheers for laity leading toward a new Methodism in their communities.

Scott Field is a retired United Methodist clergyperson and the leader of the Northern Illinois chapter of the Wesleyan Covenant Association. Dr. Field has been part of denominational renewal efforts throughout his ministry in the local church. Photo: Dunkirk – Operation Little Ships. British commemorative stamp (2010).

by Steve | Oct 7, 2022 | Front Page News, In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

As churches are disaffiliating from The United Methodist Church over theological and ethical differences with the denomination, they are considering where to affiliate next. There is a small percentage that are choosing to remain as independent congregations, a course of action we believe to be shortsighted. (See last week’s Perspective on this issue.)

As someone who was heavily involved in helping create the Global Methodist Church, I whole-heartedly believe this is the best option for local churches looking for a Wesleyan denomination with which to affiliate. Here are a number of reasons why.

1. Formed by leaders we know and trust

The Global Methodist Church was formed by people who want to see the GM Church committed to making disciples for Jesus Christ. They have served in leadership in the same Renewal and Reform groups that have worked for decades to promote doctrinal integrity and biblical positions in The United Methodist Church. These include The Confessing Movement, Good News, and the Wesleyan Covenant Association. They are dedicated to the advancement of a Scripturally-based, historic Wesleyan understanding of the Christian faith. They are people of personal integrity and a strong life commitment to the lordship of Jesus Christ. Since these leaders have a track record of faithfulness and integrity, we can confidently follow their leadership in a new denomination.

2. Centered on maintaining Wesleyan doctrine and theology based on Scripture

The GM Church embraces a warm Wesleyan theology and a vibrant spiritual outlook. It has the same doctrinal standardsas the UM Church, with the addition of the Apostles Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Definition of Chalcedon. Agreement with the doctrinal standards is required of churches aligning with the GM Church. All bishops and clergy will be expected to agree with, preach, and defend these doctrines, with robust accountability to ensure doctrinal faithfulness. The teaching of these doctrines through a new catechism will be a featured part of all GM congregations. At the same time, doctrines not considered part of the theological and ethical core are open for exploration and difference of opinion. As John Wesley said, “as to all opinions which do not strike at the root of Christianity, we think and let think.” The GM Church will have a clear vision about the “root of Christianity” and will make sure it is protected.

3. Prioritizing evangelism and church planting

GM congregations will be challenged to partner together to plant new churches and extend the evangelistic ministry of the church in their communities and in other parts of the nation and world. New churches are already being started under the auspices of the GM Church in the U.S. and in other countries. The GM Church has established a goal of planting thousands of new churches around the world during its first years of existence. We believe our congregations will have a vision for outreach and a global perspective.

4. Leaner, more effective denominational structure

The GM Church at both the general and annual conference level will rely on fewer and smaller organizational units to steer its ministry, rather than building large bureaucracies that require much spending to maintain overhead. The GM Church will partner with existing ministries with demonstrated effectiveness and commitment to Wesleyan theology to extend the church’s work, rather than building new ministries from scratch. This approach will enable much greater flexibility and adaptability to changing ministry circumstances.

5. Prioritizing the work of the local church

The local church is where disciples are made. The GM Church exists to support the ministry of the local church, not vice versa. All denominational decisions will be made within the framework of what will strengthen the ministry of the local church.

6. More resources for local ministry

The GM Church has capped the amount that a local church can be asked to contribute to the denominational structures. A maximum of 1.5 percent of local church operating income will go toward general church expenses. A maximum of 5 percent will go toward annual conference expenses. Initially, only 1 percent will go to each. More resources will stay in the local church to be used for effective ministry there.

7. No trust clause

The local church will own its own property free and clear, with no legal trust or obligation to the GM denomination. A simple, straightforward path of disaffiliation is offered for congregations that no longer find their home in the GM Church.

8. Robust accountability

Bishops, clergy, laity, and congregations will hold one another accountable to maintain Wesleyan doctrine and exhibit continued transformation and growth in discipleship. Bishops will be held accountable by a global committee of laity and clergy, not other bishops. Clergy will be held accountable through a fair and equitable judicial system. Laity will be encouraged to participate in accountable discipleship groups to support their growth in faith and Christian living. In the rare instance that a congregation welcomes teaching contrary to GM doctrinal standards or refuses to support the denomination’s work financially, it may be removed (following a collaborative dialog process).

9. Strong and clear biblical stances on marriage, sexuality, pro-life, and other bedrock issues

The GM Church’s Social Witness statements clearly define marriage as between one man and one woman, while reserving sexual relationships for marriage. Without getting into partisan politics, it states a clear pro-life stance on unborn children, while calling for greater support for women with unanticipated pregnancies. It puts forward clear, non-partisan statements on other bedrock ethical concerns, such as the value and dignity of all persons, opposition to prejudice and discrimination, concern for the poor, care for the earth, the rule of justice and law, and religious freedom. Scriptures are cited in support of each of the GM Church’s Social Witness statements. Readers are encouraged to consult the entire Social Witness section of the Doctrines and Discipline for more details.

10. A truly global church

The GM Church already has members in the U.S., Asia, Europe, and Africa. It is expected that a majority of members might be located outside the U.S. Members from all parts of the globe will be equally and fairly represented at General Conference and in the general work of the church. The denomination will be multi-racial, multi-cultural, and multi-national, learning from one another and living out the Gospel of Jesus Christ in many different ways.

11. Greater local church involvement in pastoral appointments

While pastoral appointments will still be fixed by the bishop, the local church will have greater input into whom the bishop appoints as pastor. Bishops will work with local churches to ensure their welcome of female and ethnic clergy on an equal basis. Pastoral appointments are intended to last longer, giving greater continuity to ministry.

12. A redefined role and process for bishops

While not included in the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline, leaders of the GM Church are committed to a term episcopacy. Bishops are proposed to only serve for a set maximum term, perhaps 12 years, and would not be elected for life. Bishops are envisioned as spiritual and missional leaders, while being relieved of the responsibility to administer the temporal affairs of the church, which can be delegated to lay or clergy staff. Bishops are proposed to be assigned at the call of the annual conference to ensure the best leadership match.

13. Missions through partnership

The GM Church aims to facilitate missions by horizontally linking churches and annual conferences with each other across national boundaries. Financial support for missions will generally travel directly to partners, rather than through a mission bureaucracy. The two-way exchange of volunteers and learning opportunities will foster a mutual equality among mission partners around the world. Local churches and annual conferences will become more invested in cross-cultural missions through increased direct contact with mission partners.

14. Shorter route to ordination for clergy

Rather than the 6-10 years it takes in the UM Church to reach ordained ministry, clergy candidates can expect to be ordained as deacons in 1-3 years. Ordination as elder would take an additional 4-6 years. Half of clergy education would take place after ordination, enabling clergy to integrate classroom learning with current job experience. Various educational routes will enable less expensive and more flexible pathways to ordained ministry. Ongoing clergy mentorship will be an essential part of ministry in the GM Church. Denominational support for clergy education will be a keystone of the connectional financial plan.

15. Greater flexibility in ministry and structure

With unity on essential doctrines, much greater flexibility can be given for how local churches and annual conferences do ministry, based on their ministry context. The GM Church will have minimum requirements for organization of local churches and annual conferences, with maximum flexibility and adaptability for how those structural requirements are met. Best practices will be shared across the church, so that clergy, congregations, and annual conferences can continually learn from each other and implement the most effective methods of winning people to Jesus Christ and discipling them in the faith.

16. Social Witness statements will require greater consensus

To minimize divisions over denominational positions on social issues, all such statements will require a 75 percent supermajority vote to be adopted. The focus of such statements will be more on biblical principles than advocating partisan political solutions.

17. Opportunity to build a new denomination

With the GM Church, we have the opportunity to build a new denomination for the 21st century that maintains the best of our Wesleyan tradition, while adapting our methods to fit ever-evolving circumstances and correcting for the shortcomings experienced in The United Methodist Church. Joining another, pre-existing denomination means agreeing with and conforming to a church culture and manner of operating that has been developed over decades and will not easily change. The GM Church offers a much cleaner slate on which to write the principles of an effective and Christ-centered denomination that is more flexible and adaptable to today’s world.

Churches considering affiliation with the Global Methodist Church should study the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline, which outlines how the church will function initially. A convening General Conference will flesh out details, such as the election and assignment of bishops. Churches should also contact the GM Church to invite a representative to speak and answer questions, as well as offer further clarification on what to expect.

Ultimately, the Wesleyan witness for Christ will be stronger if most of the disaffiliating churches align with one denomination, rather than splintering into various independent congregations or aligning with multiple existing Wesleyan denominations. The GM Church offers the best option for keeping the best of Methodism, while having the flexibility to try new ways of organizing for ministry and reaching the world for Jesus Christ.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo: Matt Botsford, Unsplash.

by Steve | Oct 6, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

As many United Methodist congregations are discerning their future, a small percentage who choose to disaffiliate from the denomination are choosing also to become an independent congregation. Given the dysfunction of The United Methodist Church and the denominational oppression experienced by some congregations, such a choice is understandable. It can be similar to the person who experiences a bad marriage determining never to get married again.

Becoming independent can be exhilarating. No one telling you what to do. No one demanding that you pay for this or that. No one telling you whom you must have as a pastor. You are free to structure your church as you like. You can decide as a congregation whether or not to support particular missions. It’s the same feeling one gets the first time one leaves home to live on one’s own.

Pretty soon, however, reality sets in. The responsibility of making all the decisions for a congregation without any guidance or support can become overwhelming. This is particularly true for smaller and mid-sized congregations.

That is why it is good to remember the reasons for being part of a larger denominational group.

Security in Doctrine

We are not saved from our sins and transformed into the image of Jesus by the correctness of our beliefs. But what we believe certainly influences our ability to experience salvation and informs the kind of life we live as a Christian. This is true at both the individual and the congregational level.

If we believe that everyone is going to heaven, then it is not important for us to share the good news of Jesus Christ or for individuals to surrender their lives to the lordship of Christ. If we believe the Bible is fallible, then it is all right for us to compromise the teachings of Scripture in order to be more culturally acceptable. If we believe the Bible and the Church historically are wrong about certain activities being contrary to God’s will for us, then we will be comfortable ignoring those biblical standards in the way we live our lives.

That is why it is so important for us to get our doctrinal beliefs right. Incorrect beliefs can lead us away from God and cause us to live lives that are not in keeping with God’s desire for us.

The basic tenets of the Christian faith are not up for negotiation, either by individual persons or by individual congregations. The virtue of a denomination is that it has a set of beliefs that are consistent with historic Christian doctrine and vetted by a larger body of people. This helps keep individual Christians and individual congregations from going off the rails in their beliefs and “making shipwreck of their faith.” Doctrinal accountability is essential for the Christian life.

That accountability is especially true when our theological perspective is a minority view within the overall Body of Christ in the U.S. Among evangelical circles, the predominant theology is Calvinist, whereas Methodists take a Wesleyan/Arminian perspective on theology. A colleague who is a professor at Asbury Seminary has often remarked that Wesleyan/Methodist churches that go independent tend to become Calvinist in theology within a generation of their departure from a Wesleyan denomination. Doctrinal accountability can keep our churches faithful to a doctrinal perspective that is valuable and needed in the Body of Christ today.

In Africa, many freelance independent, non-denominational churches preach a prosperity gospel. For churches there, being part of an established Wesleyan denomination can help guard against the adoption of heretical doctrines that are harmful to their members in the end.

Accountability

That leads us to the next value of denominations: a system of accountability for both doctrine and behavior. In order to be effective, accountability has to be broader than what an individual congregation or its leaders can provide. Yes, it should not have to be this way, but in our fallen, sinful condition, we have human blind spots and mixed motivations that prevent us from seeing problems or from acting on the problems we do see, especially when we are close to the situation.

Throughout my ministry, I have witnessed repeatedly a congregation victimized by pastoral leadership that transgresses the boundaries of Christian behavior. Christianity Today recently produced a podcast [https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/podcasts/rise-and-fall-of-mars-hill/] series that chronicles the rise and fall of Mars Hill Church, a megachurch based in Seattle, Washington. The congregation grew from a small Bible study to a multi-site congregation with 15 locations in four states. Weekend attendance was over 12,000. Then the founding pastor and other leaders were accused of “bullying” and “patterns of persistent sinful behavior.” Within 18 months, that giant church ceased to exist. Ironically, that founding pastor became pastor of another church and allegedly continues some of the same dysfunctional patterns.

One can reel off the names of other high-profile pastors and ministry leaders who for years perpetuated a pattern of life and ministry that was deceitful and destructive. Those with oversight responsibility were too close to the situation or the person to see the problems.

In Africa and other parts of the world, the pastor is sometimes given unbridled power in the congregation. We have heard reports of some leaders who take advantage of their position for personal gain. The church becomes an environment where those in charge decide on their own what is right, rather than looking to Scripture and denominational policies and procedures. In such an atmosphere, pastors and church members alike can be harmed by arbitrary and dictatorial leadership. Denominational accountability is the only thing that can protect pastors and church members from harm.

Denominational accountability systems do not always work the way they are intended (as our own United Methodist Church’s failures in this regard testify). But at least there is a system of greater accountability that can be reformed and made more effective. I believe the system envisioned for the proposed Global Methodist Church enhances accountability and fairness in a way that addresses some of the shortfalls in our UM accountability system. Certainly, there is a much greater possibility of holding leaders and congregations accountable when that accountability comes from outside the situation. We are often much more able to see and respond to the sins and shortcomings of others than we are in ourselves or our own families.

The Power of Collective Action

The United Methodist Church is a small church denomination. Over 75 percent of the more than 30,000 congregations in the U.S. average fewer than 100 in worship attendance. Individually, small churches have limited resources to accomplish large projects. Collectively, however, churches working and contributing together can do great things for God. That is one area where The United Methodist Church has leveraged our connectional system to make a real-world difference in the lives of people all over the globe. When it comes to hunger relief, poverty alleviation, education, ministerial training, and health care to name just a few areas, the UM Church has been able to pool the resources of many small churches to achieve significant results.

It is possible for independent churches to join associations of churches or otherwise link to support missions and ministries they agree with. The value of doing so as a denomination is to have the confidence that the missions and ministries supported by the denomination are consistent with the denomination’s doctrinal and moral standards. A denomination can make a long-term commitment to a geographic area or a certain large project that can be sustained, despite the fact that individual congregations might have to drop their support for a time, as other congregations come on board to make up the shortfall. There is a greater chance of consistency and effectiveness with denominational programs that have built-in oversight and accountability from outside (as mentioned earlier).

Providing Pastoral Leadership

One of the most important tasks of a denomination is to provide pastoral leadership to its congregations. The denomination vets and approves candidates for a pastoral position in terms of doctrine, skills, and personal lives. This is work that an independent congregation would have to do for itself, often without the expertise in personnel work and theology to make informed judgments. In the case of independent congregations, finding a pastor takes a number of months and often a year or more, during which time the congregation is without a pastor. Smaller congregations will attract fewer and less qualified applicants, whereas, in a denominational system clergy express their willingness to serve where needed.

Again, the United Methodist system of clergy placement is not perfect. Many appointments are good matches between congregation and pastor. Other times, the match is not good. Part of the reason for this mismatch is the guaranteed appointment, meaning all United Methodist clergy must be assigned a place to serve. The Global Methodist Church will not have a guaranteed appointment, eliminating the situation where clergy who are theologically incompatible or deficient in skills still must receive an appointment to a church regardless. The GM Church is also committed to more extensive consultation with both potential clergy and congregations to ensure the best possible match and to enable longer-term pastorates.

The important point is that, when done well, the denominational process can supply churches with quality, committed pastoral leaders who will help the congregation realize its potential. It can help guard against clergy who are doctrinally or personally unqualified to serve in leadership. The process can do most of the heavy lifting that would otherwise fall to inexperienced volunteers in the local congregation.

Practical Resources

What is a good curriculum for your church’s Sunday school? What would be a good Bible study on stewardship? How can we get our youth more involved in the life of the congregation? What outreach strategies might be effective in our community? What type of pension, health insurance, and property insurance should our church provide? How much should we pay our pastor?

The list of questions and decisions that a local church needs to deal with is endless. A denomination can give a local church the resources to address these questions. In some cases (like the pension and insurance question), the denomination can provide a program the local church can plug into that it could not duplicate on its own.

I am excited that the GM Church has already worked through various task forces and commissions to identify and flesh out resources and ministry models that can help guide local churches into more effective ministry in many different areas. A denomination can provide those resources and guidance for local churches in a way that the local church can trust. Those resources will be theologically consistent with the denomination’s doctrine and philosophy of ministry. Those resources will be tried and proven as workable and practical. Each congregation will not have to reinvent the wheel, but can draw upon the pooled wisdom and resources that many churches being part of one denomination can provide. Having one place to turn for ideas and guidance will save time and energy at the local level that can be effectively directed into actual ministry.

Connectional DNA

Being in connection with one another is part of the Methodist/Wesleyan DNA. The very first Methodist preachers in England were those “in connexion” with John Wesley. The personal connection with Wesley, and then the broader connection within an annual conference, was one of the hallmarks of historic Methodism.

It is being connected with one another in a common understanding of doctrine and mission that enables the benefits outlined in the paragraphs above. We have experienced the value of connection in Methodism for nearly 300 years. It is when the connection breaks down, such as when individual bishops or clergy decide to act contrary to our Discipline, that the denomination suffers.

Not only does life as an independent congregation jeopardize our Wesleyan doctrinal continuity into the future. It jeopardizes the very identity of Methodists as those “in connexion” with other Methodists. To be independent contradicts what it means to be Methodist/Wesleyan.

Much more could be said about the benefits of being part of an effective denomination. Part of a brief childhood poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow speaks to our situation:

There was a little girl,

Who had a little curl,

Right in the middle of her forehead.

When she was good,

She was very good indeed,

But when she was bad she was horrid.

United Methodists have experienced some of the horrid aspects of being in a denomination that is dysfunctional and ineffective in some key ways. The temptation is to jettison the idea of a denomination entirely, believing that we can certainly do better on our own. That is a false temptation.

We are certainly better and more effective as churches and as individuals when we work together with like-minded believers. A denomination gives us the structure and the possibility of doing just that. Together, we can make our new denomination good and experience that it can be “very good indeed!”

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo: Unsplash.

by Steve | Sep 23, 2022 | Front Page News, In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

Two weeks ago, the African Colleges of Bishops released a statement criticizing the Africa Initiative and the Wesleyan Covenant Association for, in their words, “working to destroy our United Methodist Church.” The statement also accused the Africa Initiative of “working with and supporting the Global Methodist Church, a denomination that has not been recognized by the General Conference.”

As a result of these accusations, the African bishops committed to:

- “Dissociate from any activities of the Africa Initiative and will not allow any activities of the Africa Initiative in our areas”

- “Not allow or entertain any activities of the Wesleyan Covenant Association who are wrongly influencing God’s people in our areas”

- “Not tolerate anyone giving false information about The United Methodist Church in our areas”

Since that September 8 statement, the narrative has sprung up that African United Methodists will not be joining the Global Methodist Church. It is important to clarify what is going on in Africa and what the implications are for the future of Africa in Methodism.

Who signed the bishops’ statement?

The statement is misleading, in that it lists the bishops who were present at the meeting, not those who supported the statement. We have been told by informed sources that at least two of the bishops present opposed the statement and do not agree with it. Seven active bishops were present out of the 13 total active African bishops. Some of those not present also do not agree with it. So this is a statement of some of the African bishops, but not all.

Is the WCA and Africa Initiative “working to destroy our United Methodist Church?”

The bishops supporting the statement apparently believe that any kind of separation would “destroy” the UM Church. The possibility of separation was endorsed by the 2019 General Conference by its enacting the Par. 2553 disaffiliation process. So there is official sanction for discussing disaffiliation. There is no question that the large-scale disaffiliations that are currently going on will usher in change to the UM Church. But even the loss of 20-30 percent of its members would hardly “destroy” the denomination. The bishops are guilty of hyperbole here.

The WCA, Good News, The Confessing Movement, and UMAction, have consistently had only one goal in mind for our working together with the Africa Initiative. That goal is to empower the voice and ministry of African United Methodists. The Africa Initiative reaffirms that goal in their statement of purpose:

- “To foster partnership, network, and fellowship among leaders of the annual and provisional conferences of Africa

- “To facilitate training in cross-cultural evangelism and missions, discipleship, leadership development, prayer revivals, and resource mobilization for annual and provisional conferences of Africa

- “To raise the voice of the African Church within global Methodism, by supporting the practice of biblical orthodoxy, training delegates to General Conference, and speaking out against unbiblical theological persuasions, teachings, and practices that have the propensity to misrepresent and undermine Wesleyan doctrines.”

This is not destroying the church, but building up the church.

Can the bishops effectively prohibit Africa Initiative activities in Africa?

Those bishops who have been opposing the work of the Africa Initiative in the past have already tried to stop its work in their areas. Some pastors and lay leaders have been forbidden to attend meetings or share information. The laity, in particular, have not abided by such prohibitions, believing that bishops cannot prevent people from meeting with whom they want to meet. Some clergy have needed to be more cautious due to the possibility of losing their jobs and livelihood. But the Africa Initiative has found ways to share information that do not open leaders up to the possibility of discipline from their bishops.

The attempt to assert complete control over the life of the church is a very real temptation for some bishops, especially in areas where laity defer to ecclesiastical authority. It is natural that persons who benefit from the status quo would want to preserve it. But African United Methodists will not easily allow their bishops to force them to act contrary to the people’s beliefs and interests. When several of the African bishops attempted to coerce their delegates to vote for the One Church Plan at the 2019 General Conference, the delegates voted their conscience and overwhelmingly supported the Traditional Plan.

The sharing of information and the coordinating of activities will continue in Africa.

The African members of the WCA Global Council have issued the following response:

“As leaders of the WCA in Africa, the statement by our esteemed bishops left us flabbergasted. This militant and combative position by some of these bishops does not proffer the unity and love for which they call. If anything, it opens a massive rift between them and the flock that they are supposed to look after. To openly attack your own flock diminishes the essence of being ‘good shepherds’ that the bishops are supposed to exemplify. In Africa it is generally considered disrespectful to answer back to elders, but we feel pushed into a corner, and unfortunately there is no longer any space behind us.

“The values and mission of the Wesleyan Covenant Association resonate well with what Africans believe and how we live. That makes the partnership of Africans, the WCA, and the rest of the Reform and Renewal Coalition a natural and obvious one. Further, it is most disappointing for us to realize that the Reconciling Ministries Network, which promotes same-gender marriage and the ordination of active gay and lesbian clergy, enjoys free reign in Africa to the extent of building and dedicating churches and our bishops remain very comfortable with it. As leaders of the WCA in Africa we will continue to contend for the undiluted Gospel of Jesus Christ.”

The entire response of the Wesleyan Covenant Association to the unfounded charges of some African bishops, including the above words from its African council members, is found here. The entire statement of the Africa Initiative in response to the African bishops is found here.

Rather than issuing statements attempting to stifle and control the actions of renewal-minded African clergy and laity, the African bishops desperately need to get their own house in order. For example, at least one bishop is publicly promoting and supporting the presence of U.S.-based Reconciling Ministries Network in Kenya, which advocates for same-sex marriage and the ordination of gay and lesbian clergy. In addition, the African bishops have thus far refused to call special central conference meetings to elect new bishops and retire existing bishops. Several of them are beyond the mandatory retirement age of 72, yet continue to serve and, by their plan, will continue to serve until at least the end of 2024. Another example of disregarding the Book of Discipline when its provisions are inconvenient. (The Burundi Annual Conference has asked the Judicial Council to rule on whether the African bishops must step down at age 72 and call a special conference to elect their replacements.)

Will the African church remain in The United Methodist Church?

In a report of its May 2022 leadership prayer summit, the Africa Initiative stipulated, “The Africa Initiative shall continue to encourage African churches and conferences to patiently await the 2024 General Conference while advocating for the adoption of the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation, and while acknowledging unique circumstances in some areas of the Continent that may cause members to act before then.” The strong preference of the African church is to consider the possibility of disaffiliation as annual conferences within the context of an approved Protocol that provides a clear process to follow. At the same time, there are a few countries where traditionalist pastors and lay leaders have been unjustly terminated from the church without the due process afforded by the Discipline. In those areas, it makes no sense to wait to form units of the Global Methodist Church because the individuals involved have already been forcibly “disaffiliated” from the church.

There will be some parts of the UM Church in Africa that will remain in the continuing denomination. After all, there are millions of United Methodists on the continent. As to whether the bulk of the African church will remain in the UM Church following the 2024 General Conference, that is another question. The Africa Initiative prayer and leadership summit stated, “The United Methodist Church in Africa shall not be part of a denomination that changes the current language of the Book of Discipline in order to legalize homosexuality, same-sex marriage, or the ordination of practicing LGBTQIA+ people as pastors. This is the ultimate, decisive, and undisputed position of the UMC in Africa.”

The leaders we have spoken with in Africa have no interest in remaining in a denomination that affirms same-sex relationships in contradiction to Scripture.

Is the WCA or the GMC sharing “false information?”

The official communications of Good News, the WCA, and the GMC have been careful to share information that is accurate and sourced. We have made the details of some of the examples given available upon request. So far, all we have heard are general charges of lying or misinformation, without pointing to any specific statements that we have made that are inaccurate.

No one knows for sure how the continuing United Methodist Church will evolve after separation. It is fair for different people to have different opinions, backed up by solid reasoning. Some centrists declare that the UM Church is not going to change and that traditionalists will be welcome in the UM Church. This is based only on their promises of good faith, promises that we are reluctant to trust, given the consistent violation of other promises made to us down through the years.

At the same time, there are many examples of individual clergy being excluded from United Methodism due to their traditional theological views. A number of licensed local pastors have been summarily fired by their bishop or district committee simply for sharing information about the disaffiliation process with their congregation. The majority of delegates at the 2024 General Conference will probably favor the removal of all provisions limiting same-sex marriage or the ordination of non-celibate gays and lesbians. While probably not requiring pastors or congregations to embrace same-sex weddings or gay pastors, one should not underestimate the power of peer pressure and denominational culture. Nearly all UM seminaries promote the affirmation of same-sex marriage and ordination, meaning that will be the default position held by most UM clergy trained there over the next generation. Absent intentional efforts by progressives and centrists to welcome and support traditionalist views in the denomination, it is unlikely traditionalists will long feel comfortable remaining United Methodist. So far, we have seen little evidence of such intentional efforts at theological inclusion at the denominational level.

Efforts to suppress or punish people for having different opinions by some African bishops does not indicate that traditionalists are welcome in Africa. Good News and our Reform and Renewal partners believe we can trust African people to make their own decisions without being told what to do by their bishop. Our obligation is to make it possible for them to hear our side of the story, which is only fair, since the bishops can share their side of the story unimpeded. By attempting to take coercive and punitive action against their own people, some African bishops are betraying their role as shepherds of the flock. Let us hope they reconsider their position and agree to move forward openly and amicably.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo: Greater Nhiwatiwa (in purple dress), wife of Bishop Eben K. Nhiwatiwa (left), explains the history and significance of the Chin’ando prayer mountain to bishops attending the Africa College of Bishops retreat held September 5-8 at Africa University in Mutare, Zimbabwe. Photo by Eveline Chikwanah, UM News.

by Steve | Sep 16, 2022 | In the News

By Elizabeth Fink

Would you believe me if I told you that from the age of 18 to the present, I have had at least 13 different addresses and attended eight different churches? I think it is safe to say that I had good reason to refer to myself as a nomad during my early adult years. Each place I lived offered its own unique experiences and has helped develop me into the person I am today. However, there is one challenge that presented itself everywhere I went, and that was the lack of a peer group or community of young adults that shared similar foundational beliefs. Many young adults find it difficult to cultivate that kind of formational community in or around the Church.

From my perspective, United Methodism does not offer a strong young adult ministry. The UMC’s “Young People’s Ministries” mainly focuses on children and youth. Young adults are often tacked onto that group because they don’t know where else to put them. In most churches, no one really knows what to do with young adults, so they either get ignored or attached to another group. There is a wide gap between youth ministry, college ministry, and young adult ministry, and yet churches often think of them in the same category.

What made it more difficult for me to find community was that even if I did find a young adult group, it either leaned theologically more progressive or functioned solely as a social club, with too much virtue signaling and not enough Jesus. I remember thinking to myself on a fairly regular basis, “Am I really the only traditional Methodist young adult around?” On occasion I did find another traditional young adult in UMC circles, and it was the Holy Spirit that led us to find one another. We were drawn to each other like bees to honey.

It wasn’t until I joined the WCA and got more involved that I truly began to feel like I wasn’t alone. I met more and more young adults who were seeking the same kind of community and foundation of faith I was. Many of these are spread out across the United States and even around the world, so when the idea of starting a young adult group was brought up in the WCA, I thought, “This is brilliant!”

We are in the beginning stages of creating a group called the Young Adult Methodist Connection. The Wesleyan Covenant Association sees and acknowledges the struggle for young adults to find and connect with one another and wants to help link those clergy and laity who are under the age of 40 and interested in joining the Global Methodist Church. By leaving young adults without a deep faith resource to turn to, the UMC has inadvertently stirred up a holy discontented generation of young adults who crave a deep relationship with the living Christ and are motivated to spread scriptural holiness throughout the land.

The WCA’s hope is that no one will feel alone or isolated, and that young adults won’t struggle to find others in the GMC like them who are strong in their foundation of biblical faith. This is especially important now because many of us are feeling the effects of being caught up in the toxic environment that is found throughout the UMC as it struggles with splitting. When it comes to what a young adult group needs to look like, some words that are familiar to a lot of us come to mind: “prayers, presence, gifts, service, and witness.” More than ever, young adults need a space where they are encouraged and can serve as an encouragement through prayer, testimony, and having a safe space to ask questions and to discern.

There will be opportunities for general group gatherings with the potential for events specifically geared towards young adult clergy, seminary students, and lay leaders. We will keep you informed on new developments and upcoming events. Be on the lookout for information regarding Zoom meetings, and There will be an in-person gathering next Thursday over lunch during the upcoming New Room Conference. RSVP for the lunch meeting here.

One of the exciting parts of developing this fellowship from the ground up is that we have a chance to shape it from the beginning. It will be a global community of young adults formed and led BY young adults. If you’d like to be part of forming a movement from the very beginning, now is the time to get involved.

I’m looking forward to meeting and connecting with more young adults like me spread out over the connection. We are a generation of leaders ready to enter a new denomination with excitement about the future!

If you are interested in being a part of this group or have any questions, please contact me at youngadults@wesleyancovenant.org. The young adult Facebook page may be accessed here. Feel free to share this article with young adults in your congregation or family.

Elizabeth Fink is a student at Asbury Theological Seminary and the secretary of the WCA’s Global Council. Photo: Shutterstock.