by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

Camp meetings and other types of religious services were conducted regularly by Methodists. (Lithograph of 1829 camp meeting, Library of Congress).

By William Payne –

As The United Methodist Church prepares to meet in St. Louis next year for the special-called General Conference to decide its future, now is a good time to take a sober assessment of the state of our current denomination.

• Over the last forty-eight years, it has lost over four million members. The numerical decrease equals the combined memberships of the United Church of Christ, the Episcopal Church, and the Presbyterian Church USA.

• American Methodism has declined from 6.5 percent to 2.15 percent of the American population.

• Today, one-third of the UMC’s membership is over sixty-five. Another 30 percent is between 50 and 64. Only 9 percent is under thirty.

• The Western Jurisdiction membership has plunged by 10 percent since 2013.

Sociology of religion theories explain that when churches try to lower the barrier between biblical faith and secular practices by embracing secular values, traditional members become alienated and secular people aren’t evangelized. Moreover, spiritually hungry people who could be evangelized are more likely to go to traditional churches. In short, contextualizing Christianity to accommodate secularism is not a proven approach for reaching unchurched secular people. To put it bluntly, large percentages of people are still going to church. However, the UM share of the pie has grown exceedingly small.

The marriage and sexuality debate illustrates this issue. Every U.S. denomination that has embraced gay marriage and the ordination of gay clergy has experienced drastic numerical declines. Most of those denominations rightly anticipated that traditional members would flee to other churches. However, they wrongly believed that large numbers of unchurched gay and gay-friendly people would fill the void by joining their churches. The common notion that LGBT people will become practicing Christians if the church endorses homosexuality hasn’t proven true. In reality, churches that hope to win the secular masses must challenge secular identity by presenting an alternative identity, one that appeals to some unrealized felt need and feeds a spiritual hunger that can only be satisfied through a transformational relationship with Jesus.

Fortunately, American Methodist history offers a point of reference from which the current malaise can be analyzed. Early American Methodism was evangelistically potent and fully counter-cultural. From its founding to the mid-1800s, it experienced exponential growth. In 1812, it became the largest denomination in America. This is the great miracle of Methodism. In a mere twenty-seven years from its founding in 1784, Methodism fully upended the established churches with its message of holiness, exuberant worship, and experiential faith.

The relentless emphasis on holiness and spiritual growth necessitated a corresponding stress on keeping the discipline. For example, Methodist preachers didn’t give altar calls to invite people to join the church. Instead, they pleaded with the people to flee from the wrath to come. When a hearer felt deep conviction, the awakened person would be invited to join a Methodist class. Through participation in the class, the seeker would experience guided spiritual growth. After six months to a year, the new class member could be given a class ticket and be enrolled in the society. Only those who were enrolled in society were counted as members.

Because of the need to keep the discipline, the circuit riders tested the members on a regular basis. Those who didn’t follow the rules were purged from the society or returned to probationary membership. Wesley defended the need for purging members who didn’t evidence growth in grace because half-hearted members destroyed the spiritual vitality of the church and hindered others from going forward in grace.

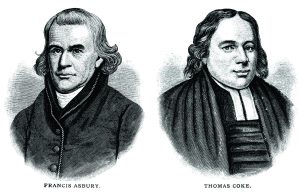

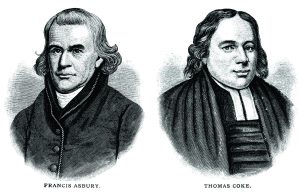

Early American Methodism was so intent on maintaining its stringent membership standards that the relationship of members to participants was 1:12. One arrives at that number from the correspondence of the bishops. In 1791, Bishop Coke bragged that the adults which made up the Methodist congregations equaled 750,000. If Coke would have included children, the number would have swelled to over one million! In that year, the membership was 61,082. In 1797, Bishop Asbury said that one million people were their regular hearers. No one knew Methodism better than Asbury.

Based on the bishops’ estimations, approximately 18.5 percent of the US population participated in Methodism during the 1790s even though the membership only equaled about 1.5 percent of the US population.

Furthermore, if one counted participants instead of members, American Methodism would have become the largest church in America a mere decade after it was founded! As appealing as that might have been, the bishops knew that they could not lower the membership standards to allow attendees to join until they accepted the discipline. Yes, in early America, being a Methodist meant that a person was a disciple of Jesus Christ.

Today, from their exalted places in heaven, Bishops Coke and Asbury are pleading with the current bishops to keep to the discipline. Will the UM bishops remember our heritage and the reason why God raised up the people called Methodist? Placating the progressive wing won’t grow the church, gain social influence, stave off massive membership decline, evangelize the secular masses, or advance the reign of God.

In addition to its disciple-making apparatus, early American Methodism grew because stalwart circuit riders bravely endured great privation to preach the gospel to the burgeoning population. Circuit riders didn’t live in parsonages or drive comfortable cars when they did their work. They didn’t even preach in many church buildings. Rather, they traveled the country by horse. Since they didn’t earn enough money to sleep in taverns, they had to get lodging wherever they could find it.

The total dedication of the circuit riders to the evangelistic mission entailed extreme poverty. Since they lived on the road and only earned $64 a year, marriage was not an option. Plus, many didn’t receive their full salary. All of this led to malnutrition, disease, and premature death. Most died at a young age. This gives new meaning to why the assembled preachers began every conference by singing the Wesleyan hymn, “And Are We Yet Alive?”

History shows that God worked through the sacrificial efforts of the small army of Methodist preachers. They covered America in a loose web of circuits and corresponding preaching points. In time, that network led to the founding of an evangelical church in every city, hamlet, and outpost in America. Rapid membership growth and social transformation followed. In short, early American Methodists didn’t accommodate the culture. They changed it!

Yes, God raised up American Methodism to evangelize the land and spread the message of holiness. In fact, the work of early Methodists was so successful that it did more to shape the Christian ethos of the emerging American Republic than any other social force. Furthermore, the spiritual foundation that it helped to lay is a primary reason why America has not gone the way of Western Europe and Canada.

As United Methodists look forward to the specially called General Conference, the delegates must consider the unfinished business of the last General Conference. Before the UM Church can look forward and see with clarity where God wants it to go, it should look backward and rediscover why God raised up this church. A denomination that separates itself from its heritage and its ethos will never find spiritual vitality, social influence, or numerical success.

The future of American Methodism is in the balance. Thankfully, a new report from Harvard University gives cause for great optimism. “Recent research argues that the United States is secularizing, that this religious change is consistent with the secularization thesis, and that American religion is not exceptional,” reports sociologists Sean Bock and Landon Schnabel in Sociological Science. “But we show that rather than religion fading into irrelevance as the secularization thesis would suggest, intense religion—strong affiliation, very frequent practice, literalism, and evangelicalism—is persistent and, in fact, only moderate [secular] religion is on the decline in the United States…. The intensity of American religion is actually becoming more exceptional over time.”

In truth, God has left an open door in the American landscape. Secular and moderate religion won’t succeed. Evangelical churches have an opening to discover a secular field that is ripe unto harvest. Will United Methodism remain true to its heritage and mobilize an army of dedicated preachers to evangelize the secular masses? If the UM Church doesn’t go through the open door and reap the ripening harvest, God will give American Methodism’s torch to another church. The choice is ours.

William P. Payne is the Harlan and Wilma Hollewell Professor of Evangelism and World Missions at Ashland Theological Seminary. He is an ordained United Methodist elder in the Florida Annual Conference and the author of American Methodism: Past and Future Growth (Emeth, 2013) and Adventures in Spiritual Warfare (Wipf and Stock, 2018).

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

God Outwitted Me: The Stories of My Life by Maxie Dunnam (Seedbed). Hopefully you’ve already read one of Dunnam’s many books or heard him preach. God Outwitted Me is his spiritual memoir about the events that molded and strengthened him to be the prized and beloved Christian leader and communicator that we have come to depend upon within The United Methodist Church.

God & Gangsters: 21 Tales from Gangland by Chris Ahrens. In this self-published book, Ahrens interviews nearly two dozen “shot callers, armed robbers, dealers, made men, violent racists, and murderers” who testify to discovering new life with Jesus Christ. As he writes, “Something or, rather, Someone had moved them, and because of that they chose to bow to the Throne rather than die in the Chair.” (More info: Godngangsters@gmail.com).

Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music: Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock by Greg Alan Thornbury (Convergent). This is a captivating biography about one of the most intriguing, controversial, and thought-provoking Christian singer/songwriters. Norman was a complicated musical pioneer with a prophetic edge who had an enormous influence on both musicians who were anchored in their faith and those who weren’t really sure what they believed.

The Spiritual Gifts Handbook: Using Your Gifts to Build the Kingdom by Randy Clark and Mary Healy (Chosen). This is an exceedingly helpful book about the spiritual gifts spoken of in the New Testament. Erasing misconceptions, Clark (Protestant) and Healy (Catholic) provide an insightful exploration of the gifts given by the Holy Spirit to be used by Christians.

Kingfishers Catch Fire: A Conversation on the Ways of God Formed By the Words of God by Eugene Peterson (Waterbrook). The life of congruence urges us to live in sync with what we believe – to practice what we preach and to stretch ourselves between what is written in the Scriptures and how we live that out. Those familiar with Peterson’s poetic preaching will thoroughly benefit from this volume.

The 19 Questions To Kindle a Wesleyan Spirit by Carolyn Moore (Abingdon). Like Moore’s preaching, her writing is powerful, relatable, convicting, and energized by the flames of Pentecost. She leads readers through Wesley’s historic questions for ordination with both frankness and grace. For lay and clergy alike, the questions probe and challenge.

The 19 Questions To Kindle a Wesleyan Spirit by Carolyn Moore (Abingdon). Like Moore’s preaching, her writing is powerful, relatable, convicting, and energized by the flames of Pentecost. She leads readers through Wesley’s historic questions for ordination with both frankness and grace. For lay and clergy alike, the questions probe and challenge.

![Mapping Out the Valley of the Shadow of Death]()

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | May/June 2018

Original art for Good News by Sam Wedelich (www.samwedelich.com).

By Elizabeth Glass Turner –

Laughing hard enough to shake dust from the rafters while reading a book about death feels a little sacrilegious, like stifling giggles at a funeral. It doesn’t seem proper. It doesn’t seem respectful.

But while funerals have nice social protocols and traditions for guiding times of grief, the time before the funeral doesn’t. There isn’t an order of worship for waiting on hold while wrestling with insurance companies over cancer treatment coverage; there isn’t a liturgy to follow when someone you know is going through grueling chemotherapy. Left to our own devices, our good intentions can stack up on someone like a sliding pile of Blue Cross statements. When we add blanket theological go-to sentiments, the result can be a 21st century replay of Job’s friends. But if we can’t, like the Man of Sorrows, allow ourselves to be “acquainted with grief” when others are suffering, how on earth will we learn to stare our own in the face when the time comes? And come it will.

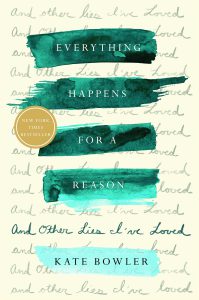

By now, you may have seen, heard, or read an interview with Dr. Kate Bowler, a church history professor at Duke Divinity School. Long after her years growing up among Canadian Mennonites, recently she has been on The Today Show, NPR, and in the pages of the New York Times, in addition to countless conversations with faith-based publications. Kate is in her 30’s. She and her husband have a young child. A couple of years ago, she was (eventually) diagnosed with Stage IV cancer. Barring a miracle, she won’t get better: but she isn’t yet dead. She is a resident of the valley of the shadow of death. Kate lives two months at a time, from one scan to another. She notes that experts told her, “You have a thirty to fifty percent chance of survival.” By their definition, survival meant two years of life.

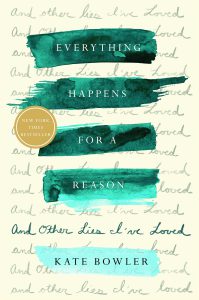

Bowler’s wry title – Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved – isn’t a frontal assault on the sovereignty of God. This isn’t a story of a Christian losing faith in hard times, either. Nor is it a denial of supernatural intervention. Rather, it signals what is coming: dark humor, brutal honesty, and faith in the midst of suffering. Bowler’s memoir is like sitting with a friend who has removed all her makeup and starkly answers your inquiry about her health by silently showing you her scars, burns, and lesions while mocking the absurdity of it all.

In a twist, Bowler’s pre-cancer dissertation also plumbed the subject of suffering – particularly, the prominence of the prosperity gospel – “a theodicy, an explanation for the problem of evil.” In other words, if God is all-good and all-powerful, why do bad things happen? Bowler studied prosperity preachers, attended church services where prosperity and blessings were promised. She sympathized with desperate people, struggling with poverty or illness, vulnerable to promises of overflowing health and bank accounts. But in a bittersweet turn, following her diagnosis, she came to a realization:

“I would love to report that what I found in the prosperity gospel was something so foreign and terrible to me that I was warned away. But what I discovered was both familiar and painfully sweet: the promise that I could curate my life, minimize my losses, and stand on my successes.”

On top of her own implicit assumptions that God wanted her healthy and successful (and what Christian bookstore isn’t stocked with titles about finding your purpose and living into your calling?), she then encountered a similar prosperity theology among a multitude of North American Christians:

“The world of certainty had ended and so many people seemed to know why. Most of their explanations were reassurances that even this is a secret plan to improve me. ‘God has a better plan!’ ‘This is a test it will make you stronger!’ Sometimes these explanations were peppered with scriptures like ‘We know that for those who love God all things work together for good.’ Except that the author, Paul, worshipped God with every breath until his body was dumped in an unmarked grave.”

In a chapter simply called Surrender, Bowler slices like a skilled surgeon wielding a scalpel: “Control is a drug, and we are all hooked, whether or not we believe in the prosperity gospel’s assurance that we can master the future with our words and attitudes. I can barely admit to myself that I have almost no choice but to surrender. When will I realize that surrender is not weakness?”

What Bowler exposes when she cuts beneath the surface is the simple truth that the more things change, the more things stay the same.Cancer treatment has morphed tremendously over the past 100 years; human nature has not. We still catch ourselves saying, “God, who did something wrong, against your will – this man, or his parents, that he was born blind? Was it his theology? Did they not pray? Weren’t they using essential oils? Shouldn’t they have had a better job with better insurance? Did she eat organic while she was pregnant?”

And when Jesus was asked, “whose fault is this, Frank’s fault, or his parents’ fault? Why was this guy born blind?” Jesus responded – none of them did anything wrong. When the thief on the cross asked Jesus to remember him in his kingdom, Jesus didn’t send down an army of angels to save the thief’s life: no, the thief died that day. Conversion didn’t extend his life on earth so that he could go be a witness to the power of Christ, which would have made pretty great sense to me. When Jesus was born, dozens or hundreds of chubby little toddlers in the region were murdered; we don’t sing nativity songs about that, but human tragedy accompanied the birth of the Son of God.

Sometimes when we read the Gospels, we forget that Jesus didn’t blink. Jesus didn’t turn away, cover his nose to stifle stench, or hurry away. Jesus – Jesus leaned in. Whether he encountered people with disgusting, contagious skin diseases or shriveled legs or crusted-over eyes, he reached forward, and he touched. For Jesus, there was no stigma associated with suffering, mental illness, or disease. And if there is one way that the church in America has forgotten how to be like Jesus, it is this Mother Teresa-like response to physical suffering. Bowler probes discomfort with illness, suffering, and lack of control by asking:

“What would it mean for Christians to give up that little piece of the American Dream that says, ‘You are limitless’? Everything is not possible. The mighty Kingdom of God is not yet here. What if rich did not have to mean wealthy, and whole did not have to mean healed? What if being people of ‘the gospel’ meant that we are simply people with good news? God is here. We are loved. It is enough.”

In the end, Bowler eviscerates the malignant notion that Christians deserve to be happy, well, and prosperous (ideas that would have shocked early Christians and still surprise people of faith in other parts of the world); she sighs at verses lifted out of context and plastered on refrigerator magnets; and she relaxes into the great, costly gift of presence. This incarnational turn pivots our response of words to a response of action: we cannot always explain, but we can pick up groceries and deliver them. We (often) don’t have an answer, but we can sit and bear listening in silence to another’s unbearable grief. We may shake with fear at what could go wrong in our own lives, but we can, like Jesus, lean in and reach forward and affirm the beauty of the person in front of us.

Kate Bowler, author of Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I Have Loved. Photo courtesy of Random House.

Reading Bowler’s short but weighty volume repeatedly brought a precious Flannery O’Connor quote to mind: “faith is what we know to be true, whether we believe it or not.”

Anyone who has traveled the dark night of the soul is familiar with this truth. Day to day emotions or perspectives oscillate; faith is what remains in spite of ourselves – or well-meaning others. This kind of anchor is helpful to anyone facing the possible end of their lives, no matter the age, no matter the diagnosis, whether it’s a good day or a very, very bad one.

Kate is hiking the valley of the shadow of death, marking the trail with frank observations as she goes before many of us and lives in the in-between: no longer healthy, not yet on hospice, two months at a time. She is a guide to those near death, and to those still in denial about our fragile human mortality. She is a guide to those who simply drop off homemade cookies, and a guide to those so uncomfortable with sickness and uncertainty that they want to solve it instead of putting an arm around it. In this way, she has leaned in; she has reached out; she has not blinked.

Elizabeth Glass Turner is a frequent and beloved contributor to Good News. In addition to being a writer and speaker, she is Managing Editor of www.WesleyanAccent.com.

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

TMS Global’s GreenLight programs offer young adults a 4-6 week mentor-led experience that guides them as they try to discover God’s leading in their lives. This team (pre-med mission-minded students) spent time serving alongside medical personnel in Ghana. For more information about GreenLight, contact jwheaton@tms-global.org.

By Sarah Parham –

We have all read the reports, the gloomy news that young people are leaving the church in masses. A Fuller Youth Institute study shows that roughly 50 percent of young people who grow up in the church leave the church behind, along with the piles of caps and gowns and high school sports trophies. No one needs a news feed to tell us this. It’s visible in the pews we sit in. It can cause us to lose hope.

But after more than a decade in college ministry, I can say with confidence that many Christian young people I know who are exiting the church are actually in pursuit of the kingdom. They are looking for a church that isn’t contained in four walls. They are looking for something more expansive, more missional. They are seeking a church to go to on Sunday that would be with them Monday through Saturday as well—touching the things they touch, loving the people they love. And this gives me hope!

But how might these young people stay connected to church? How can we, as church members, be an ally in helping them discern how God might use them in His mission in the world?

Don’t have the answers. Young people’s experience of the world is different than any other generation. They cannot stay uninformed of issues and tragedies in faraway places. The problems of other nations are being tweeted and broadcast in their pockets every day. Terrorism isn’t something that happens on foreign soil, but in New York City. Young people want to know what Jesus says about these things.

It can be rather intimidating. Their questions can be hard ones: “Is Jesus serious about taking care of the poor? He talked about that a lot. What is the church doing to help?” We might be tempted to squelch such questions because we don’t have the answers.

But that’s just it. We often don’t have the answers. And that’s not even the point. In my experience working with college-age youth, I noticed that when they asked hard questions, so often they weren’t trying to figure me out or to pin me or the church to the wall. They were trying to figure themselves out. They were trying to understand where their place was in this big, beautiful, and very messy world.

So how can we respond to their questions in a way that satisfies the questions beneath the questions?

Listen to the heart. The transition young people go through is so subtle, adults can miss it. Of course, young children ask why about everything. At some point, though, the why starts to be asked for a new reason. The question goes from “Mommy, why is that man asking for money?” to, years later, “Why is he sleeping outside when I go home to a nice bed?” In other words, as a person grows into adulthood, the question shifts from “Why is the world this way?” to “Why am I in the world this way?” When we miss the twist in the question, we miss the opportunity to speak into the lives of young people about that most precious thing: calling.

So at this junction, keep engaging. Listen to what Jesus is doing in this person. What breaks her heart? What inspires him to do more? What are his talents? What are the things that make her come alive — or the things that keep her up at night? What are the things that make him question?

It gets tricky when we hear hard questions over and over again. But be encouraged. So often, when God is moving in people to do something — like calling them to missions, for example — His call may be experienced as a holy unrest. In other words, there begins a stirring in the spirit that things aren’t the way they should be.

So when young people come to us with their questions, what if we return the questions back to them by asking, “What do you think God is saying in these questions? What if the answer lies in you?” By our questions, we might help them see that the things they notice that are not right could be the very things God is calling them towards. As we do this, we might actually help them discover their place in the mission of Jesus.

And, says the Fuller Youth Institute, we might also help them stay connected to the church. The Institute released a study on the phenomenon of young people leaving the church post high school. They found that there is one X-factor for keeping young people engaged in the church. Listening. When young people have a non-related adult who knows them well and is actively engaged in their lives, the chances of their keeping the faith and staying engaged in a church/campus group throughout college and beyond increases dramatically.

Set them free. If church people ask me what they can do to attract young people, the first thing I ask is what their missions program is like. I often get quizzical stares. Some proceed to tell me about their church’s youth program, or how much money they give to missions. But that’s not the heart of my question.

The reason I ask about a church’s missions program is because young people don’t want to sit on the sidelines and observe. They want to get involved with something meaningful. They want to be involved in missions and outreach. And their doing this might actually mean that they will leave our churches to go elsewhere, even to some other part of the world.

So instead of losing our young people, let’s launch them. Let’s listen to their questions. Let’s help them discern how God desires to use them in the world. Let’s resource them, and then let’s set them free to join Jesus in His mission. This, after all, is the ultimate goal of a missional church.

Sarah Parham is TMS Global’s director of mobilization and candidacy. She holds a Masters of Divinity degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. This article was reprinted from the Fall 2017 issue of Unfinished, the publication of TMS Global. Used by permission.

by Steve | May 15, 2018 | Magazine Articles, May/June 2018

By Eduard Khegay, United Methodist Bishop of the Eurasia Episcopal Area –

By Eduard Khegay, United Methodist Bishop of the Eurasia Episcopal Area –

Nikolai Berdyaev (1874-1948), Russian religious philosopher, wrote in the beginning of the twentieth century that Russian thinking cannot be Eastern or Western. He argued that both of these extremes are not appropriate. His hope for Russia was that she would grow to global leadership, and wake up the inner creative activity of the people. This reminds me of our global United Methodist Church and the importance of a multidimensional view when we deal with issues of our time. We as a church also cannot be Eastern or Western. We need to learn how to bless and enrich one another with our gifts and graces.

The purpose of my essay is to challenge our global church to look deeper. While the issue of human sexuality has moved to the top of our attention, I see it only as a trigger of deeper issues we face today.

In this essay, I will analyze our global movement from my Russian/Eurasian perspective. I will present my position on leadership, take a critical view of Western democracies, reflect on Scripture and Wesleyan tradition, and share my thoughts on unity.

I share this text in the spirit of humility and hope that you will not perceive it as a judgmental “expert’s view,” but accept it as a good challenge to look at our global church differently.

Crisis of Leadership

I love stories. They communicate values and have the power to transform lives. One story I learned from an American friend is about U.S. President Harry S Truman, who had a sign on his desk with the phrase “The buck stops here.” He wanted to remember that as president he carried the ultimate responsibility for making decisions. This story reminds me of my role to lead and carry ultimate responsibility for my decisions as a bishop of The United Methodist Church. While I am convinced that each bishop works hard to lead his or her episcopal area, I find it very puzzling how we lead as the bishops collectively.

I realized at the 2016 General Conference that we have a crisis of leadership. It was quite surprising to hear from delegates that they wanted us, bishops, to lead. As bishops, didn’t we already know that we needed to lead? It is obvious that our global church requires new ways of leading that are different from leading at local or even national levels. And while the United Methodist structure and decision-making processes can be improved and reinvented, what lies underneath is the way we as bishops relate to one another.

Can you imagine a fruitful organization that is led by leaders who do not fully trust one another and cannot have honest conversations? Can this team of leaders lead through intensified parliamentary procedures and learning more about legal issues? I cannot see how we can lead our global church this way. My prayers and hopes are that someday we as bishops will take more action to build trust and have honest conversations about challenges our church faces today.

For me, the litmus test of trust and honesty among leaders in the organization, especially the church, is how much is discussed in the official meetings and how much is discussed in the corridors. Can leaders trust one another enough to bring the same questions to the official meeting that they discuss in the corridors? Or do we simply want to be polite and politically correct so we do not offend one another? Since when have politeness and political correctness in the church become higher values than trust and honesty?

This brings us to the next important issue for our global United Methodist body: unity. The Methodist movement has enjoyed unity and faced divisions during several centuries of its history. We struggled with the issue of slavery. The Church of the Nazarene, for example, left The Methodist Church and challenged us to practice deeper holiness and simplicity. Our present debate on human sexuality has challenged our unity as a global church. Suddenly we have realized that we understand human sexuality and sexual orientation differently depending on geographic region, culture, theological background, and biblical interpretation. The more important question for me is this: can we have unity in the UM Church without unity at the Council of Bishops? Again, unity at the council is related to the previously stated issue of trust and honesty.

Hey – maybe if I had ten million dollars today, I would invest them in building unity at the Council of Bishops! We need to figure out how to relate to one another and build a spirit of trust among ourselves. Can we model that for our global body? Some may find it too idealistic, given the fact that we speak several different languages, belong to multiple cultures, come from different continents, and live in extremely diverse economic and political systems. May we be reminded that the miracle of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost gave birth to our Christian church and united so many different people as they built trust and honesty in ministry with one another and to the world! The buck stops at the leadership level, and we as bishops have to figure this out. The present crisis of leadership can become an opportunity to do something we’ve never done before with transformational change and reform, leaving a long-lasting legacy for the future of The United Methodist Church.

Western democracies and the rest of us

I have experienced several disillusionments in my life. One of them was during my life in the Soviet Union, when I realized that the Communism we were building was not actually the one that I read about in Lenin’s books. I learned later that you cannot force people of the world to love Communism by using tanks and soldiers. Another disillusionment was when I studied in the United States. I realized that while democracy gives so many great opportunities and freedom to people, the people struggle with as much loneliness, racism, and addictions as they do in nondemocratic countries. I learned that you cannot force people of the world to love democracy by using airplanes and missiles. Here I want to juxtapose a few aspects of life to show that things are perceived and managed differently around the globe. And as a global denomination, we must take a serious look at these differences.

First, let’s look at legal and relational differences. It is no secret to any United Methodist who has experienced another culture that, generally speaking, life in Western democracies is fast paced. People are goal oriented and busy. In most other places of the world, though, relationships are of such high value that being together is often more important than personal goals. As one who grew up in Kazakhstan, in the former Soviet Union, I love my Central Asian culture. And even after twenty plus years of living in Moscow, I feel much more comfortable in my hometown of Almaty, drinking tea with my friends and sharing our lives, than achieving another new result in the twenty million-population megapolis of Moscow. That is not to say that we will not reach our goals. But as a global denomination, relationship must be our priority. Fifteen-minute coffee breaks will not do it – especially when coffee is not even my favorite drink!

The danger Western democracy projects onto the church is legalism. The way many of our Eurasian delegates experience General Conference is often very shocking. Legal matters, parliamentary procedures, appeals to Judicial Council, manipulations of points of order, disrespect toward presiding bishops – these are some of the things I have never experienced in my non-Western culture; and hope I never will. This is not the church I believe God desires to build. We read in the Acts of the Apostles: “Every day, they met together in the temple and ate in their homes. They shared food with gladness and simplicity. They praised God and demonstrated God’s goodness to everyone. The Lord added daily to the community those who were being saved” (Acts of the Apostles 2:46-47, CEB). One can sense the spirit of relationship rather than legalism.

So maybe if I had ten million dollars today, I would invest them in building relationships among our people on a global level! Maybe that sounds too idealistic. Well, when I visit churches throughout my episcopal area, sometimes my Moscow goal-oriented drive is unsettled when we drink tea for three hours, or eat borsch soup for four hours, or when people ask me to visit their home briefly and we share our stories long after midnight. In the process I find myself puzzled as to when I start my “work.” But after three days like that, I realize that people feel blessed and inspired by being able to share their stories with me, by being able to serve food for me and just be together, building relationships and friendships. Then I realize that building relationships is a higher goal than the one I had in mind. People are energized to grow in Christ and serve others through relationship. This is the beauty of relationships, and we need to develop this more on a global scale. Again, I would say that quick coffee breaks or even lunches (especially business lunches) won’t do it.

Second, let’s talk about human rights and morality. During the twentieth century, the Western democracies excelled at protecting human rights. Indeed, if not for Western democracies that promoted the value of human life and freedom of conscience, our world would likely have drifted more deeply into darkness. However, this focus has gone to the extreme during last few decades. To my cultural shock, I see teenagers manipulating the juvenile justice system; young people behaving disrespectfully toward elderly people in the name of freedom; and many propagating gay relationships as a norm and silencing those who stand for traditional families. I cannot accept that.

What I observe in Western democracies is that morality is often replaced with human rights. When I visited the Annual Conference of the Methodist Church in Britain some years ago, I heard one speaker from Samoa. He passionately challenged the audience with something like this: “When you came to us as missionaries you told us: ‘Dress up!’ [implying that Pacific Islanders’ dress was improper for Christians to wear]. Now I come to you, fellow Methodists in Britain, and say: ‘Dress up!’ [implying the devaluation of morality in this Western democracy].”

I must share with you that I value and love many achievements of the Western democracies. I am forever grateful that I became a Christian because of a U.S. missionary. I feel so blessed to have studied in a U.S. seminary. Many people I admire in the Christian world come from Western Europe and the U.S.A. But in today’s crisis of The United Methodist Church, I feel like part of our church in Western democratic countries acts like NATO, which keeps pushing its agenda and ignoring the United Nations. We do not want to repeat the same mistake NATO made in Iraq and Afghanistan. Our churches in the Western democratic countries cannot push their agenda on our global church, ignoring the fact that we are a worldwide body.

I hope our church continues to stand for human rights and teach people the value and sacredness of human life. But I hope even more that our church stands for morality and teaches people what God desires from us and what the Lord condemns. The extreme quest for human rights leads toward extreme individualism, which ignores the collectivism, solidarity, and shared morality so central to Christian experience and tradition. This is interconnected with the previous point on the relational aspect of Christian community and also brings us to the next point.

Third, worldly influence and holiness are critical to our future together as the church. One of the Ten Commandments tells us to observe the sabbath day and treat it as holy. God’s example and God’s design for creation teaches us holiness. As Christians, we are called holy in the Bible, people who are “called out” in this world – people who live by higher standards. We are people who are shaped by relationships with the Holy One every day. That changes everything.

What I observe in the countries with Western democracies is that worldly influence has gradually taken over some churches. Being moral and preaching holiness is not trendy anymore. Instead, individualistic desires to use marijuana freely, legalize weapons, redefine God-given understanding of family, and accumulate more wealth than one can use during a lifetime become modern idols. Many people living in other countries see this as the worldly attack on churches and Christian faith.

One may argue that we lose people because we are not trendy in the society. I would argue that we lose people because we do not consistently strive toward holiness. When you live a holy life, different from the world, you might risk people laughing at you or blaming you for not being loving or just. But Jesus walked this way before us, and he made it clear for people to understand what is holy and what is not. He spent time with the poor and outcasts of society, and he rebuked Pharisees and scribes. Jesus never played with the trendy influences of his time. His message was clear, challenging, unsettling, and transforming. He wants us to be holy because God is holy.

Why do I find these things of high importance for the United Methodist global body today? It is because we are a global body. But the problem is that we are managed as an organization within the Western democracy. And that brings me to my final point in this section.

Fourth, we must address the global nature of our church with its power, money, and politics. The history and nature of the Christian church is such that its leaders from Western democracies sent missionaries to spread the gospel into many continents. They had money and power. In many ways, the rest of us feel like children of our mother church. Our mother was proud of fast growth, exciting results, amazing Christian education, and the alleviation of poverty. She has gladly shared resources with her children. But children began to disagree with mother as her opinions on the issue of human sexuality changed. That is when children had to learn that, unfortunately, even in the church, power, money, and politics are very real.

Suddenly, the children learned that mother would no longer love and support them if they continued to disagree with her. It turned out that mother was no longer satisfied with how much her children contributed, although she had been happy to give them everything abundantly when they listened to her and followed her directions. She began to ignore her own democratic rules that she had taught her children to follow. The majority voice will not stop her because she has the power, money, and politics. She has become so political that her children can neither understand her nor even speak her language. She wants to keep pushing her agenda even if that means losing her children.

Scripture and Wesleyan tradition

Conflicts and disagreements happened in the church historically, and they will continue to challenge our global church as we continue to learn what Scripture means for us today and how we continue to spread scriptural holiness throughout the land and strengthen our Wesleyan tradition. I am convinced that just as God created in the early church, God will create something new through this present conflict in the United Methodist movement. For some, it is a new interpretation of Scripture and a new definition of marriage. For others, it is renewed and strengthened traditional understanding of Scripture and marriage. It is obvious that these realities differ depending on the culture and context in which you live today. How do we continue as a global body? Let me give you one extreme illustration.

As you may know, polygamy is a reality in Africa. Our sisters and brothers have struggled with this issue for many years. Yet we as Christians hold the very orthodox position that monogamy is a norm. Can you imagine our sisters and brothers in Africa disturbing our General Conference with their protests, ignoring the voices around the world, and forcing us to bless polygamous marriages in our own contexts? I cannot imagine that.

Our Wesleyan tradition uses Scripture, reason, tradition, and experience as four authoritative sources together. The current crisis in our church challenges us to “test the spirits to see if they are from God” ( 1 John 4:1 CEB). One can see and feel how Scripture is picked and used to “baptize” what people want to believe rather than what the text says to us. Some people base their position heavily on the experience of their lives or the lives of their family members and friends. Others emphasize tradition that has kept the Christian church alive through the centuries and trials and persecution. The genius of the Wesleyan tradition is that we keep these four quadrilateral parts in creative tension and let the Spirit move us forward. Come, Holy Spirit, come!

What is Unity?

The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church has been an important document, reflecting our unity among many things. Not anymore. Today, I cannot explain to my sisters and brothers in the Eurasia Episcopal Area why some United Methodists break the Discipline while others have to follow it. This is an important time for us to reflect again on what unity is.

As I envision the future of The United Methodist Church, I am confident that our church must have the unity of its leaders first. We need deep listening for one another and to learn from one another. We need to build trust and practice honesty. Where the covenant has been broken, we need time for restoration, healing, and a new level of relationship.

The buck stops with us bishops. I do hope and trust that the General Conference will make a new way forward for our global movement. This, however, would not automatically improve unity in the Council of Bishops and guarantee trust and honesty in our relationships. We need to do it – the sooner, the better.

Shared Christian values, morality, and holiness are important aspects of unity. You cannot have unity between husband and wife if one thinks that adulterous relationships are acceptable, while the other remains fully committed. I hope that our worldwide Methodist movement will constantly strive toward holiness and have a powerful witness with influence in the modern world – our modern world ruled by the “selfie-centered” lives of “my rights” and “my freedom.” The Christian movement has always inspired people to be holy and be together rather than live “selfie” lives.

Our Christian faith is full of tension when it comes to power, money, and politics. How do we use these gifts and graces to sacrifice and empty ourselves, to deny ourselves, to take up our cross and follow the Holy One? Will we hold these gifts as weapons to fight, or will we be willing to be crucified with Christ and experience the Resurrection?

Let me conclude with my personal story. As I was writing this essay, presidents Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin had their first face-to-face meeting in Germany during the 2017 G20 Summit. I am perfectly aware that these two names awake a lot of emotions in us, both positive and negative. As a child of the Cold War who was told that Western countries were going to drop a nuclear bomb on the Soviet Union, I still remember those high school drills when we put gas masks on our faces and hid under the table to practice our actions in case of nuclear war. But God brought me to faith in Christ, and through our church I learned that I have sisters and brothers in Western countries who not only do not want war with us in the East, but they also love us as God loves them. They pray that God would use their presidents as instruments of peace. This was a transformational experience for me.

So, when I see presidents Trump and Putin talk with each other, I am hopeful and reminded of Nikolai Berdyaev’s thought that we cannot be Eastern or Western. We are called to be together and bless one another whether we come from East or West, North or South. Like our church at Pentecost, let us continue to meet and share food with gladness and simplicity, listen to one another, praise our God, and serve others. And the Spirit of God will move us forward.

Eduard Khegay is bishop of the Eurasia Episcopal Area of The United Methodist Church. This article (originally titled “In Christ there is no East or West”) is taken from Holy Contradictions (Abingdon Press, 2018), a collection of essays representing diverse responses on how United Methodists can live in the Wesleyan tradition in times of disagreement. The seventeen contributors include among others Tracy S. Malone, Thomas Lambrecht, Rob Fuquay, Audrey Warren, and Philip Wogaman.

Eduard Khegay is bishop of the Eurasia Episcopal Area of The United Methodist Church. This article (originally titled “In Christ there is no East or West”) is taken from Holy Contradictions (Abingdon Press, 2018), a collection of essays representing diverse responses on how United Methodists can live in the Wesleyan tradition in times of disagreement. The seventeen contributors include among others Tracy S. Malone, Thomas Lambrecht, Rob Fuquay, Audrey Warren, and Philip Wogaman.