by Steve | Oct 11, 2010 | Magazine Articles

By Liza Kittle

“I sought the Lord, and He heard me, And delivered me from all my fears…This poor man cried out, and the Lord heard him, And saved him out of all his troubles.”

—Psalm 34:4,6

As I write these words, my 18-year-old daughter Frances is walking to her first college class at the University of Georgia. I know she is filled with fear and anxiety, even though my husband and I have encouraged her repeatedly that she will do great. My 22-year-old daughter Caroline is busily preparing for her senior exit show at the Savannah College of Art and Design, the climax of her college experience. I know she is anxious about the exhibit and filled with fear about her future as she takes the next step into adulthood.

A close friend, only forty-six years old, with a loving family and three beautiful sons, is fighting the battle of her life with stage IV colon cancer. I know she has fears about the future, even though she is praying and trusting Jesus for complete healing. Another childhood friend has just learned she has cancer in her trachea, liver, and brain. She fears the months ahead not knowing who will provide and care for her husband, who struggles with health issues due to a heart transplant.

A dear pastor I know, who preaches the gospel with passion and faithfulness, has been relieved of his pastoral duties by a bishop and small group of disgruntled church members. An abrupt change in a job or ministry surely involves fears and trepidation. Another pastor friend in Uganda faces daily challenges from financial hardships, persecution, and societal corruption—causing anxiety and fear.

All human beings will undoubtedly face the gripping fear that hardships and troubles inevitably bring and Christians are not immune to this reality. The beauty of being a Christian, however, is that we have been given resources to face any fear or circumstance. We have Jesus.

The psalmist in the above passage doesn’t ask the Lord to take his fear away. He cries out and seeks the Lord’s face, enabling Jesus to break the grip these fears have on him. Jesus doesn’t always save us from the storms in our lives, but he does desire to save us in the midst of our troubles. It is in the dark and painful places that Jesus is waiting to be our protector, provider, and deliverer—if we earnestly seek his face. When we have Jesus to cling to, our fears can turn to thanksgiving and praise as we experience the overwhelming peace that only Jesus can bring.

In the scenarios described above, what will happen in each individual circumstance isn’t yet known. But whether the person involved has a relationship with Jesus Christ will determine how their journey will proceed. The presence of Jesus in a person’s life can insure a miraculous victory over fear.

The available resources described in Psalm 34 include: the angel of God surrounds and delivers those who revere God (v.7); the favor of God falls on those who cry out and seek his face (v.4); those who look to the Lord are radiant and their faces are never covered with shame (v.5); the Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit (v. 18); the Lord redeems his servants and no one will be condemned who takes refuge in him (v. 22).

The scriptural promises of Psalm 34 were recently played out in a miraculous way in the life of Paul Mabonga, the Ugandan pastor described above. In 2008, his nine-year-old niece, Jackline, disappeared from the home of a friend in a neighboring village. After exhaustive attempts to locate her, the family began to fear the worst. Every year in Uganda, children are kidnapped by human traffickers and witch doctors who steal children for brutal sacrifice rituals. Throughout their lengthy ordeal, Paul and his family faithfully clung to Jesus, crying out to God and trusting in his promises.

In August 2010, the police in a distant city contacted Paul with the miraculous news that Jackline had been found! She had been cared for by a foster family while police had searched for her family. While the circumstances of her ordeal are still being investigated, Jackline, now eleven years old, was reunited with her family—a homecoming filled with tears of joy and thanksgiving. It was only by their unrelenting trust and dependence on Jesus and the promises of God were their fears turned into a miracle.

Are hardships and troubles overtaking your life? Is anxiety and fear immobilizing your daily living? God has provided resources to deliver you from this bondage. Renew is here to provide encouragement, prayer, and support in the midst of your circumstances. Let us know how we can be of service to you in ministry. With Jesus, any fear can be conquered.

Liza Kittle is the President of the Renew Network (www.renewnetwork.org), P.O. Box 16055, Augusta, GA 30919; telephone: 706-364-0166.

by Steve | Oct 11, 2010 | Magazine Articles

By George Mitrovich

In the past 50 years, while the U.S. population grew by 127 million, mainline churches lost more than five million members—led by United Methodists, who lost more than three million.

The math is incontrovertible and undeniable: While America experienced exponential growth; mainline churches experienced catastrophic loss.

Why?

If you’re a Methodist and a disciple of John Wesley, both the evangelical Wesley and the Wesley who confronted social injustice, you view membership losses as a theological crisis; a failure by many in our church’s leadership—bishops, district superintendents, and clergy—to honor Wesley by failing to keep the vows they took upon ordination as ministers into the United Methodist Church.

The greatest losses suffered by our church have occurred in the theologically most liberal of our jurisdictions, Northeastern and Western. It would be disingenuous to argue the first hasn’t affected the second, but that is often the argument made in attempting to explain these traumatic losses.

If churches lose their dominant White Anglo/Saxon membership because communities evolve from Anglo/Saxon to Asian (for instance), how does that change the church’s calling? There’s no hyphen in the language of God. John 3:16 has no asterisk. Jesus died for more than Ozzie and Harriet, David and Ricky.

If you look at those United Methodist churches that have experience remarkable growth such as Church of the Resurrection in Kansas City, Faithbridge in Houston, or Ginghamsburg Church in Ohio, you find churches led by pastors who honor John Wesley; pastors who actually believe the confessions and creeds of the United Methodist Church; pastors who do not suffer theological angst, but preach that Jesus is who he said he was (John 4:26).

Am I saying Adam Hamilton, Ken Werlein, and Mike Slaughter never have theological doubts? No, but they, unlike too many of their colleagues, choose to believe and act upon the sacred vows they took when they were ordained—and the results are persuasive.

In 1945 at a conference in Wales, C.S. Lewis warned the Church of England of the consequences that would come if Anglican clergy continued in their priestly duties while recanting the church’s historic faith. C.S. Lewis’ prophecy has tragically come true—as is evident every Sunday in England’s shockingly empty churches. (A few notable exceptions would include London’s All Souls Langham Place, the church of John R.W. Stott, as well as Holy Trinity Brompton, home of the Alpha Course.)

What is true in the Church of England is increasingly true in the U.S. Great Methodist churches, especially in the northeast and west, have been reduced to small and aging congregations, mere shadows of their once glorious past.

The consequences for the United Methodist Church are devastating, but so too are the consequences for our society, which desperately needs our Wesleyan witness and social ministry; a witness and ministry that once made the Methodist Church the greatest of America’s Protestant churches.

It’s a hard thing to say, but I am compelled to say it: Methodist clergy who no longer uphold our doctrines and beliefs have betrayed their vows—and betray our church.

Monumental losses in membership and disappearing Methodist congregations may be more than the failure to honor our Wesleyan heritage, but if that isn’t it, pray tell what is?

George Mitrovich, a San Diego civic leader, is a member of that city’s First United Methodist Church—the largest congregation in the California-Pacific Annual Conference.

by Steve | Oct 11, 2010 | Magazine Articles

A West Coast Lament

By Steve Beard, 2010 —

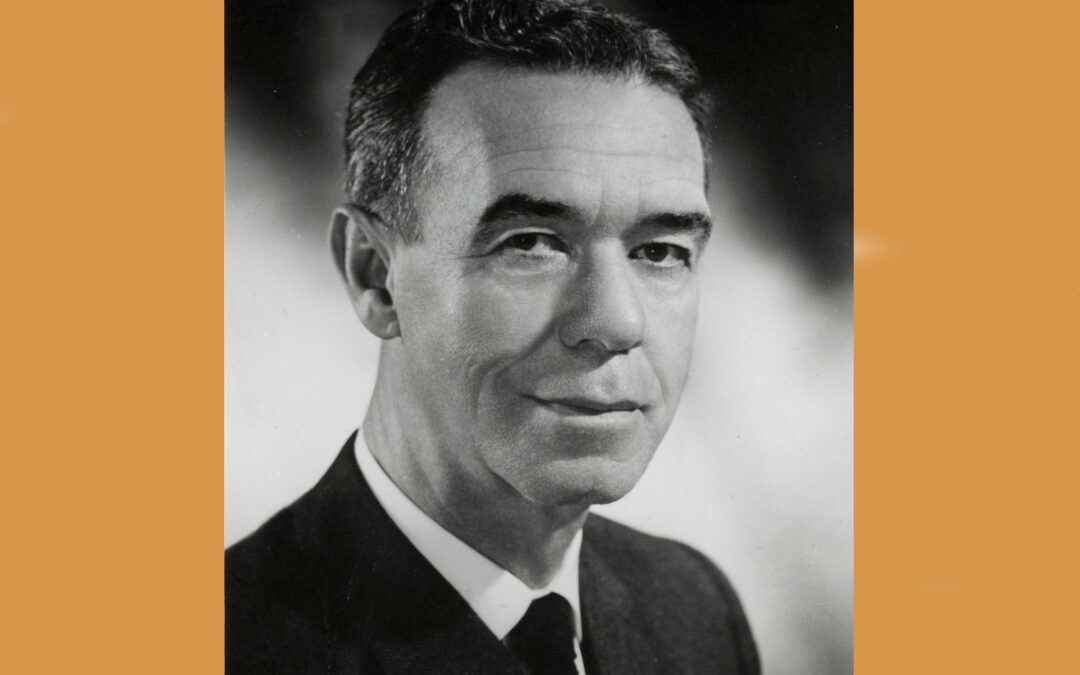

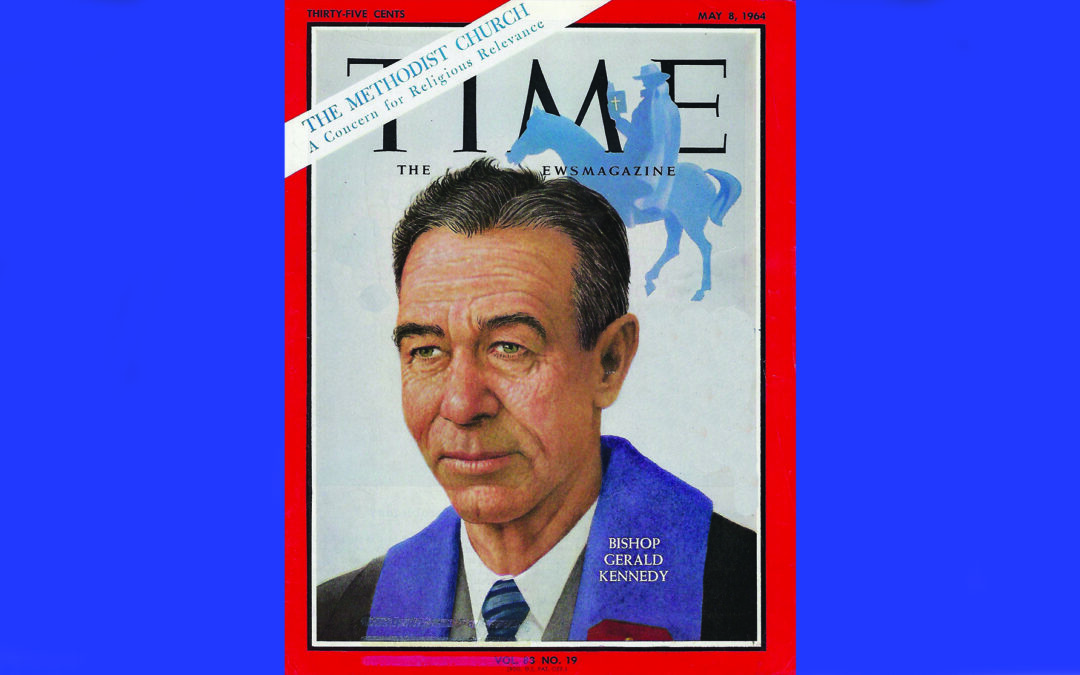

There was good reason that Bishop Gerald Kennedy of Los Angeles presented the Episcopal Address at the 1964 General Conference of the Methodist Church. “Kennedy is unquestionably among the four or five most dazzling preachers in the U.S. today—an oratorical genius with a commanding baritone, and the pace and timing of a Broadway pro,” wrote Time magazine in a cover story on Methodism’s identity crisis a week after the General Conference.

“This year many of the 858 Methodist delegates arrived at their conference with the deep conviction that their church had reached a turning point in history,” reported Time, “and with a scarcely concealed fear that the vitality that once burned in Methodism was lost when fiery evangelism gave way to today’s organized, institutional church.”

In his address, Kennedy told the delegates that the Christian task is “to pursue our ancient course of attacking our own imperfections, keeping our life open to God, and perfecting our society. We are not trying to sell a system, but to demonstrate a Way which is incomparably better than all others, and shines with the promise of a more abundant life for all men.”

Incomparably better than all others. Now that took some chutzpah back in the 1960s. But that was Kennedy. Elegant, gracious, confident, and firm. He was appreciated by conservatives and liberals alike. Although not narrowly categorized as an evangelical, he was the chair of the Billy Graham crusade in Los Angeles in 1963. A prolific preacher and author, Kennedy was independent, smart, urbane, accessible, and spellbinding. When it was time for his sermon at annual conference, preachers literally ran across campus to grab a seat.

Kennedy had a distinct understanding of Southern California culture. He drove around in a convertible Karmann Ghia Volkswagen sports car and preached a trademark sermon called, “A Little Old Lady from Pasadena,” a pop culture nod to the Beach Boys. When his fellow bishop Fred P. Corson of Philadelphia complained about the difficulty of getting his clergy to wear clerical collars in the 1960s, Kennedy used to jokingly respond, “I have a hard time getting my clergy to wear shoes!”

Time observed that Kennedy “best seems to express the peculiar quality of his church’s active, outgoing faith: pragmatic but perfection-aimed, equally concerned with personal morality and social order, loving discipline yet cherishing freedom.” Kennedy called it “sanctified common sense.”

At that time, Kennedy was spearheading the fastest-growing area of the Methodist Church. It was a golden era of buying property, building churches, and extending the tent pegs of Wesleyan Christianity on the West Coast.

A tale of two conferences

Not long ago, Andrew Miller, president of Providence Publishing House, was shocked by the decline of what he considered his home congregation, First United Methodist Church of Riverside, California. When his father was appointed there in 1967, there were more than 2,700 members. Currently, that congregation reports only 346 members.

“It has an enormous physical plant, expansive parking lot, and is in an area of well-populated family homes. There is nothing visible to the eye to explain its decline,” writes Miller in his analysis, A Tale of Two Conferences.

Utilizing the General Minutes of the United Methodist Church, Miller diligently studied the growth and decline of half-a-dozen annual conferences within the denomination. His study ended up comparing the California-Pacific Annual Conference and the North Georgia Annual Conference since they had similar memberships in 1965.

At that time, California-Pacific’s membership stood at 218,352 (92,692 attendance); North Georgia’s membership was at 211,794 (attendance 85,838).

Today, California-Pacific’s membership in 2010 is 81,194 (48,584 attendance). North Georgia, on the other hand, has a current membership of 356,279 (127,486 attendance).

For those doing the sobering mathematics, North Georgia’s membership has swelled by 144,485 since 1965, while California-Pacific’s membership has diminished by 137,158.

Since 1950, North Georgia has had 99 churches that at some point had more than 1000 members. There are currently 72 congregations at that level.

During that same period of time, California-Pacific has had 82 churches with more than 1000 members. Currently, there are only five.

Miller was stunned by the stark data.

So was I. Both of us were raised in Southern California as United Methodist preacher’s kids. I remember skateboarding up and down the sidewalks of the University of Redlands during annual conference as a teenager and growing up within the small but potent subculture of evangelical United Methodism on the West Coast—a unique minority status.

(Editor’s note: In 1985, the Arizona/Southern Nevada portion of the California-Pacific Annual Conference became the Desert Southwest Annual Conference. For the purposes of his study, Miller eliminated those congregations from the statistics.)

A different place

Miller’s study can be used as an illustrative example of two areas of the church pursuing diametrically different spiritual worldviews. Over the years, Cal-Pac has embraced the prevailing theological liberalism and gay activism of the Western Jurisdiction—a section of the UM Church that has lost 45 percent of its members in the last 40 years. For example, during the 2010 annual conference, seven different presentations were given at Cal-Pac to highlight gay, lesbian, and transgender concerns.

North Georgia, on the other hand, has maintained and promoted an overall orthodox theology and upheld traditional United Methodist sexual ethics. This is not to say that there are no liberals or progressives in North Georgia any more than it is to say that there are no evangelicals or traditionalists in Cal-Pac. It is, however, to say that each annual conference has a prevailing theological and ethical outlook.

It is understandable that when most analysts look at the data of the two conferences, they first note the obvious distinction between the perceived “Bible Belt” culture of Georgia, and the “happy pagan” vibe that permeates California.

“The leading difference is diversity,” responded Bishop Mary Ann Swenson when I corresponded with her about the comparison. And she has a point. In addition to Southern California, her area encompasses Hawaii, Guam and Saipan. Almost 60 percent of families in Los Angeles have a language other than English spoken at home. As I grew up in the parsonage, my dad’s ministry included helping launch a Spanish-speaking congregation, as well as Vietnamese, Tongan, and Korean congregations.

When Bishop Swenson’s pastor in Mississippi called her forward to the altar 41 years ago and laid his hands on her head, he prayed for her to be an evangelist and missionary to the “wild West.”

“I have learned that, compared to my home in the South, the West is not so much ‘wild’ as it is profoundly different in religious and cultural terms: this is the context for my ministry—our ministry,” she responds.

Not long ago, Los Angeles surpassed New York and London as the most religiously pluralist metropolitan region. There are more than 600 separate faiths with religious centers in the area.

At the same time, Los Angeles is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic—3.6 million strong. Of those, 70 percent are Latino. The second largest religious representation is Judaism, followed by the Southern Baptist Church, Mormonism, and Islam—the third largest concentration in the United States. Of course, there are cults and pseudo-religions on every corner.

Protestantism in Los Angeles is overwhelmingly evangelical, Pentecostal, or charismatic. Today, the mainline denominations represent a very small segment.

By way of comparison, Atlanta is overwhelming Southern Baptist, followed by United Methodists and Roman Catholics.

Pacific Homes

In our exchange, Bishop Swenson mentioned the Pacific Homes litigation from the late 1970s to the early 1980s as a “difficult time in this region and accounts for some of the decline in those decades.” Once again, she has a point. It was a public relations disaster for United Methodism in Southern California. These church-related retirement homes in California, Arizona, and Hawaii ran into catastrophic financial problems and subsequent legal issues. I remember the talk around the parsonage of lawsuits, liability, bankruptcy, and families leaving our congregation.

Bishop Charles F. Golden (who followed Kennedy) appeared before “60 Minutes” cameras and front page stories appeared in the newspapers. This was a denominational earthquake that threatened to burst the Richter scale. Providentially, Bishop Jack Tuell, a former attorney who followed Bishop Golden, helped guide Cal-Pac through the rigorous and tedious legal and financial issues that threatened the annual conference.

In the painful process, Cal-Pac had to slash its budget and move the conference headquarters into the Pasadena First United Methodist Church. The repercussions of the Pacific Homes debacle would be felt for many years.

Measuring vitality

“Focusing exclusively on congregational membership isolates the question of vitality from the context of mission,” Swenson believes. She points out that membership statistics are not the sole measuring stick to test vitality. Although the membership in Cal-Pac has declined 16.5 percent over the past ten years, attendance increased over 2 percent during the same period. Furthermore, Swenson notes that despite Cal-Pac’s decline in membership over the last 10 years, giving per member increased 45 percent.

“Yet the more fundamental constraint is not visible in numbers and dollars,” Swenson continued. “As much as I love our United Methodist Church, I am convinced that we are attempting to operate out of one size fits all model of evangelism, combined with an assumption of homogenous contexts for ministry. That homogeneity does not exist, and to ignore it is to attempt a ministry that is disconnected from reality. Measurement of ministry based on that assumption is equally disconnected from reality.”

While no one wants to measure ministry on assumptions that are disconnected from reality, it would be worth having a denomination-wide discussion about whether United Methodism actually has a serious “model of evangelism” at all.

The numerical loss of members carries significance because individual souls matter. Perhaps United Methodism has lost sight of the great weight of one lost soul looking for redemption. Are we convinced that the lost even need to be found?

In the beginning of August, evangelist Greg Laurie held his 21st Harvest Crusade at Angel Stadium in Anaheim. Over three nights, more than 118,000 men, women, and children attended the event. How many United Methodist congregations officially partnered with the crusade? Zero.

Stadium crusades are not everyone’s cup of tea, nor are they the normative model of United Methodist evangelism. Nevertheless, would we not benefit by occasionally venturing outside the confines of our denominational family to see what is working and what is making a difference?

Hispanic influx

The Immigration Act of 1965 would prove to transform the ethnic make-up of Southern California. For example, the Hispanic population of Los Angeles is nearly 50 percent. Spanish services are held in two-thirds of the Catholic parishes.

In all honesty, United Methodism is not the only group to have lost a tremendous opportunity with Hispanics. All of the mainline denominations have failed. “The most interesting thing about the Latino population in Southern California is that they have their own churches, some imported here from other countries, some growing up here,” observes sociology professor Richard Flory, senior research associate at the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California. “But, they do seem to be either Catholic or some version of evangelical, Pentecostal, or charismatic.”

In my conversations with Cal-Pac clergy, I asked why United Methodism never gelled with the Hispanic population. “We viewed them as a social justice project instead of an opportunity to share our faith,” said one pastor. This sentiment was expressed repeatedly. It seems as though we have been held captive by a false dichotomy of social justice vs. outreach. The Roman Catholics and Pentecostals embrace a both/and approach instead of an either/or model. United Methodism would have been wise to have done the same.

If United Methodism intends on making any inroads with Hispanics, we must be intentional about having pastors, evangelists, and teachers speak Spanish and be willing to Pentecostalize some of our services. Furthermore, our annual conferences must attempt to have a greater understanding of Latino culture.

Many years ago, I was a guest preacher at a Methodist annual conference in Mexico. Over meals, many of the pastors asked me about the preoccupation with homosexuality within the UM Church in the United States. One by one they recounted the public disgrace they faced as Methodists when the Rev. Ignacio Castuera, a prominent UM clergyman in Cal-Pac, appeared on the “Cristina” television show to perform several same-sex marriages in 1995. Cristina was the Oprah of the entire Spanish-speaking world.

Castuera was decked out in a clerical collar and a colorful stole draping his robe as he smiled with glee as the male couple and the female couple kissed on television. These pastors in Mexico received the brunt of the ramifications of his actions. Their parishioners were disillusioned and angry. As in the United States, many left the Methodist church for other denominations where this was viewed as unscriptural. These pastors bore an undeserved stigma among the people in their towns just for being Methodists.

Although the bishops of Mexico sent letters of protest and concern, there never came a satisfactory response. This is the kind of situation that guarantees United Methodism could remain an alien faith among Hispanics.

Missing the youth culture

Some of United Methodism’s diminished effectiveness in Southern California had to do with an “inability or unwillingness to adapt to the emerging youth culture starting in the 1960s, and probably just in general being considered too ‘establishment,’” sociologist Richard Flory told Good News. “I think as well that theology also played a role in that in general, the message from mainline denominations was more social gospel oriented than what evangelical and Pentecostal/charismatic churches offered, which in one way or another has always focused on…a personal religious experience, journey, quest, or worship experience.” Wesley would have referred to it as having his heart “strangely warmed.”

Southern California was an epicenter for an enormous religious revival among the counter-culture in the 1960s and ’70s. “Jesus is alive and well and living in the radical spiritual fervor of a growing number of young Americans who have proclaimed an extraordinary religious revolution in his name,” reported Time in 1971 in a cover story on the Jesus People. “Their message: the Bible is true, miracles happen, God really did so love the world that he gave it his only begotten son.”

The church in Santa Ana pastored by my dad that I grew up in had a barefooted Jesus People youth pastor. My dad knew the intense cost—and paid the price—of attempting to merge the countercultural with the “establishment,” but he had a heartfelt commitment to the next generation. Unfortunately, not enough of our mainline clergy had the same passion for evangelism and belief in the transforming power of God to find a way to welcome the John-the-Baptist hippies to a coat-and-tie Sunday morning service.

The spiritual vacuum, however, was filled with entirely new and dynamic denominations. The flagship congregations for such movements as Calvary Chapel, The Vineyard, and Hope Chapels exploded with growth all over the west coast.

Let’s be very honest about the fact that there never has been a problem with growing a large church in Southern California. Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church is just one example of vibrant evangelism, passionate worship, and meaningful social action.

Liberal fundamentalism

As Cal-Pac’s primary seminary, the Claremont School of Theology establishes the theological tone of many pulpits throughout the Western Jurisdiction. Claremont’s decision to become an interfaith graduate school of religion that trains Muslims, Christians, and Jews under the same roof was not terribly surprising to those familiar with its theological underpinnings.

In making his pitch for the seminary’s new vision, Claremont President Jerry Campbell told the United Methodist Reporter that Christians who feel they need to evangelize persons of other faiths have “an incorrect perception of what it means to follow Jesus.”

Huh?

“I think the correct perception is much more on the side of learning to express love for God and love for your neighbor as yourself,” Campbell said. “Those are the fundamentals for me.” The wording was very clever, but ultimately intellectually and theologically confusing and inadequate. Our love for our neighbors is at some point most potently expressed by sharing with them the life-changing power and love of Jesus Christ. To withhold that winsome message does no honor to God nor our neighbor. As Wesley said, “Offer them Christ.”

We are not talking about beating anyone over the head with the Bible, but we are talking about being serious about the message of Jesus: “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.”

“We have lost the idea of the uniqueness of Jesus Christ,” said one young Cal-Pac pastor. “The gospel has been reduced to doing good things—kind of a religious version of the Lion’s Club. People are looking for much more than that.”

Church planting

“As new areas develop, new congregations must be organized,” observes Miller in “A Tale of Two Conferences.” “North Georgia has dedicated staff working full time on new congregational development. Several other conferences showing growth have such staff assigned as well. Cal-Pac has no large membership category churches that have been founded since 1975. In the same time period, North Georgia established fourteen of its large membership churches, as well as a number of others approaching this level.”

“There is an expectation that every local church can grow and there is a commitment within the annual conference to begin new missions, ministries, and congregations every year,” says Bishop Mike Watson of the North Georgia Annual Conference.

“There is a place for many diverse people including Anglos, African-Americans, Hispanics, Koreans, Kenyans, Vietnamese, Brazilians, Haitians, and others,” Watson told Good News. “We have every size congregation from the tiny to the extremely large. We have inner city, urban, suburban, county seat, small town, and open country congregations….There seems to be a welcoming place for everyone.”

Lyle Schaller, the prolific church growth guru, believes that there should be a “chief strategist in every annual conference (this could be a person or a task force) with the competence plus the responsibility and authority to fill that role.”

After surveying the comparative data, Schaller told Good News, “The North Georgia Conference has been organized for at least four decades with someone, or some group, filling the role of chief strategist and the strategy affirms that larger congregations are more likely able to mobilize the resources required to produce the relevance, quality, and choices younger generations seek as they search for a church home than are small churches.”

Kennedy’s call

As they gathered in Pittsburgh for the 1964 General Conference, delegates believed that their church had reached a “turning point in history,” as Time reported. Many were fearful that the “vitality that once burned in Methodism was lost when fiery evangelism gave way to today’s organized, institutional church.”

To refocus the passions, structures, and vision of the church that he loved so much, Bishop Kennedy reminded the delegates in his Episcopal Address of the evangelical roots of their heritage and the divine calling of the Methodist Church.

“The Wesleyan revival was, among other things, a demonstration that when plain men could say in the words of the founder, ‘We have felt our hearts strangely warmed,’ thousands were converted,” Bishop Kennedy said. “While our fathers were good organizers, they regarded organization as a means to fulfill the evangelistic purpose. Their success was a testimony to the power of witnessing to Christian experience and another example of how the preaching of the Word of God saves men by faith.”

In times like these, we all need to be reminded of that.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Steve | Oct 11, 2010 | Magazine Articles

By Heather Hahn —

The United Methodist Church can experience revival by returning to the spiritual practices of Methodism’s early years, say two scholars leading an effort to develop passionate lay leaders.

In joining the mainline establishment, the church jettisoned many of the activities that made John Wesley’s movement so vibrant, said Scott Kisker, associate professor of church history at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C.

“Methodism was a method of helping people, a discipline that enabled people to have their lives transformed by the gospel and become holy,” Kisker said. “Mainline means we are an establishment religion that basically doesn’t see much difference between creating good citizens and creating Christians.”

In the 18th century, Methodist preachers took to the road to share the gospel and Methodist laypeople gathered each week for class meetings to discuss the state of their souls. Often the class leaders—rather than ordained clergy—performed pastoral duties for their communities.

It was all a bit countercultural. The early Methodists were the Jesus freaks of their day.

Kisker and the Rev. Steve Manskar, director of Wesleyan leadership for the United Methodist Board of Discipleship, would like to see the church recapture some of that 18th century spirit.

To help with this revival, Manskar and Kisker will lead the Wesleyan Leadership Conference on October 14-16 at West End United Methodist Church in Nashville, Tennessee. The theme of the conference derives from Kisker’s book Mainline or Methodist? Rediscovering our Evangelistic Mission. Manskar is working to get United Methodist congregations across the country to establish Covenant Discipleship Groups, based on the model of lay-led class meetings.

“Lay leadership is essential,” Manskar said. “That’s where the revival is going to come from. We need to have laity taking the lead in the visiting, the caring, and the mission of the church.”

Small group vitality. The conference comes on the heels of a recently released Congregational Vitality study that identified small groups as one of the main “drivers” of church growth, attendance, and giving.

Such a finding would not have surprised John Wesley. Kisker said small groups were a key part of Methodism from the beginning.

Wesley started out with band meetings, intimate groups divided by sex and marital status where people met weekly to confess their sins.

At band meetings, participants each had to answer five questions:

• What sins have you committed?

• What temptations have you met with?

• How have you been delivered?

• Do you have any questions?

• Do you have any secrets?

“It was a way to experience God’s grace,” Kisker said, “and have more compassion on your neighbor.”

Wesley next added class meetings where people could discuss how well they were following Jesus’ teachings. At a time when professional clergy were scarce, class meetings led by lay men and women became one of the core units of Methodism.

Membership in the Methodist church required membership in a class meeting, Kisker said. A person who missed three class meetings risked being dropped from the church rolls.

However, as the church grew in size and its members grew in prosperity, Methodists started to want to be more like their Presbyterian and Episcopal neighbors, Manskar said. They stopped wanting to attend class meetings each week, and they wanted pastors who no longer traveled but served one congregation.

By the middle of the 19th century, many of the circuit riders had dismounted, and such practices as field preaching and class meetings had fallen by the wayside.

In the process, many laity lost their passion for discipleship. The church still attracted new members. But as a percentage of the U.S. population, it stopped growing sometime after the Civil War, Kisker said.

“I think we became more about building an empire and less about creating disciples for Jesus Christ and redeeming people,” Kisker said. “We became more about building a church instead of building the church.”

Applicable today. The practice of class meetings still works amid people’s busy 21st century schedules, Kisker and Manskar said.

Kisker is part of a class meeting with fellow members of Hyattsville (Maryland) United Methodist Church. The group usually gathers in a member’s house on Friday evenings.

“We’ve seen some amazing things happen—people making dramatic life changes,” Kisker said. “One woman who was a lawyer decided she was going to become a nurse.… I just think making yourself aware of what God is doing in your life and having someone who asks you about it every week is pretty profound.”

Manskar hopes Covenant Discipleship Groups will lead others around the country to have similar profound experiences.

In these groups, members hold each other accountable for following Wesley’s three simple rules: Do good, do no harm, and stay in love with God. The goal, Manskar said, is “to witness to Jesus Christ in the world and to follow his teachings through acts of compassion, justice, worship, and devotion under the guidance of the Holy Spirit.”

Fairmount Avenue United Methodist Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, which has a weekly attendance of about 200, has seven such groups of four to seven members.

They meet for about an hour each week. Members go around in a circle sharing what they have done in the past week as acts of compassion, justice, worship, and devotion. Then they discuss their spiritual promptings and share prayer requests.

Dan Thielen, a member of one of the groups, said the gatherings help him think about what is important in his life.

“We support each other through the bad times and pat each other on the back in the good times,” he said.

The Rev. Michelle Hargrave, the church’s senior pastor, said she and others have seen their faith deepen because of their Covenant Discipleship Groups. She is a member of a group with six other women.

“It’s such a foundational piece of Wesley’s own thinking, and it lives out in our lives so concretely,” Hargrave said. “That’s a pretty exciting tool for the church.”

The Wesleyan Leadership Conference costs $95. Further information is available at www.gbod.org/wesleyanleadership.

Heather Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service.