by Steve | Aug 9, 1973 | Uncategorized

Supremacy of Christ

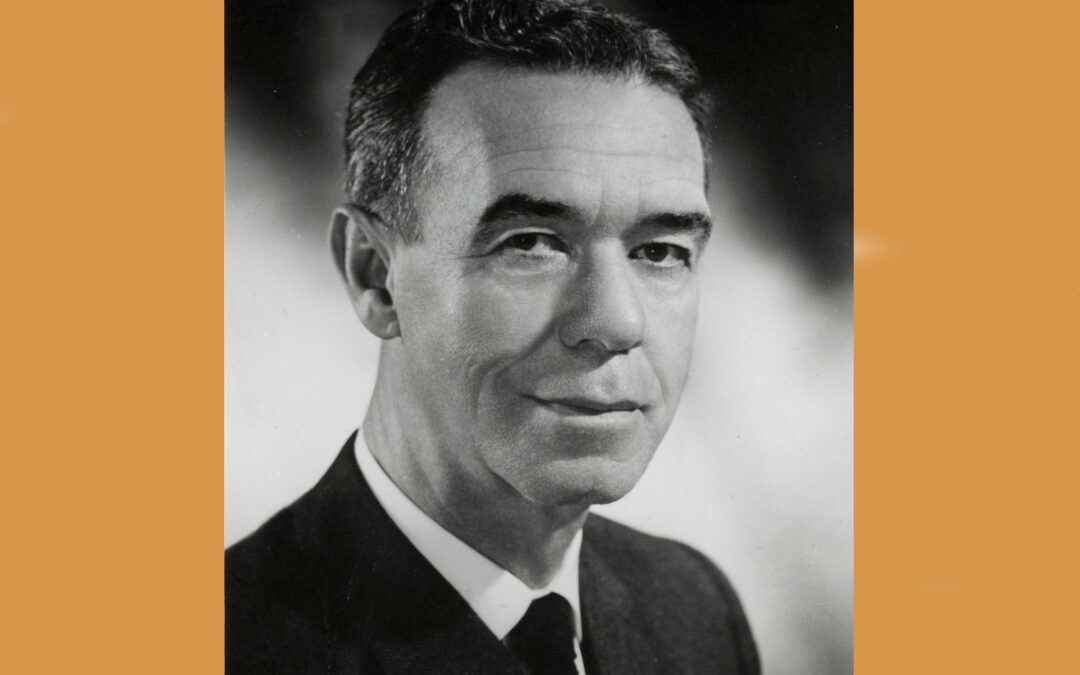

By Bishop Kenneth W. Copeland

Summer 1973 (died at the age of 61 in August of 1973)

“And God placed all things under his feet and appointed him to be head over everything for the church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills everything in every way. (Ephesians 1:22-23)

Jesus Christ is the Head of the Church, His Body. This is the message Paul is affirming without any reservation whatsoever. The Church has been at its best at those times when it has been most committed to this irreversible truth. When the Church fails to be the Church, when it fails in its witness to the world, it is because it fails at the point of recognizing and responding to Jesus Christ as Head of the Church.

Today the divine call is for the Church to see with the eyes of Christ, to hear with the ears of Christ, to think with the mind of Christ, to love with the heart of Christ, to heal with the hands of Christ and to speak with the voice of Christ. If I read the mind of this Convocation correctly, I believe that is why we’re here. And what we believe the mission of the Church is all about. I believe this truth is absolutely basic to everything we talk about, hope for, pray and work for with respect to the renewal of the Church. What does concern us is that the Church will make a vivid and vital rediscovery of Jesus Christ as its Head and recommit the message and mission of the Church to His will in our day.

There is far more in these verses than any one human being can fully comprehend. However, it is both our duty and our privilege to examine what Paul is trying to say here under the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

First, Paul is proclaiming the supremacy of Christ, the preeminence of Christ. The Layman’s Bible Commentary paraphrases part of verse 18 in this manner: “Christ is the source of the Church’s life, since He rose first from the dead that others might rise through Him. Thus in all things, in Church as well a.s universe, He shows Himself supreme.”

How very important this is – and always has been – to any adequate understanding of the Church and its witness in the world! In the days of his flesh, our blessed Lord confronted his disciples with this question, “Who do you say I am?” On the answer to that question, the Christian and the Church either stand or fall. Nothing else matters very much if that question is not answered correctly, within the limits of our own humanity and the limits of our faith.

No creeds, no activism, no philosophy, no resolution, no dialogue, no restructuring of organizations, no church program nor policy will avail much which does not arise out of a firm conviction that “You are the Christ, the Messiah, the Son of the living God.”

It makes a great deal of difference who we believe Jesus Christ is. Here is the profound and decisive difference between the Christian faith and all other religions. It separates them not in degree but in kind. Religions are man’s search for God; the Gospel is God’s search for man.

The Revised Standard Version has it that “in everything He might be preeminent.” Everything! “For in Him all the fulness of God was pleased to dwell.” The Greek word translated “fulness” means totality. That is, the totality of divine powers chose to make their abode in Him. This phrase, therefore, claims full deity for Christ.

There’s a difference between divinity and deity. Not many people debate the divinity of Jesus Christ. Divinity is an attribute of God. Therefore, love is divine. Truth is divine. Beauty is divine. The Christian home is divine. The Church is divine. Divinity is an attribute of God, but Deity is God. The incarnation is the one great irreversible fact of history. God revealed himself in the human dimensions of Jesus. Witness the question of Philip, for example, at the Last Supper, “Lord, show us the Father, and we shall be satisfied” (John 14:8). Jesus answered, “Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father … ”

Dr. John Lawson is Professor of Church History at Candler School of Theology. In his book An Evangelical Faith for Today, he said, “The evangelical must insist that a further essential to the Christian system (without which the whole falls and upon which there can be no compromise) is that our Lord is the unique, divine incarnation in the full historic sense of the word. He’s the divine son made man, fully human, fully divine, one real Person, the permanent union of God with his handiwork, and the personal entry of God into the history of this world.” Let us reaffirm our unquestioned belief in the supremacy, the preeminence of Jesus Christ. The effectiveness of the Church’s witness in the world, in both the personal and the social dimensions of human life and society, depends upon the full acceptance of this truth, and our obedience to it.

Another great truth which comes to us from this Colossian passage is the power of Christ. It’s not accidental, my dear friends, that the Great Commission of our Lord is predicated by Jesus’ affirmation that all power had been given to Him, both in heaven and on earth (Matthew 28:18). Then follows his promise that he will be with us always, even unto the end of the world.

The intimacy of His divine companionship and the promise and provision of His power are set within the context of mission. Now let us add to the promises inherent in the Great Commission, the promise that he gave his disciples just before his Ascension to the Father “You will receive power after the Holy Spirit is come upon you, and you will be witnesses unto me in all Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). The greatest need of the Church today is this power Jesus promised us we could have. Yet perhaps no dimension of the Church’s life and ministry is quite so misunderstood. It is popular, relevant and contemporary to talk about power structures within the Church. It’s also popular to demand a “piece of that pie.” For some, it is the “in” thing to organize our own power structures to fight the established power structures, fighting fire with fire. The end result is that all of us are severely burned in the process, and the Kingdom of God grinds down to a slow walk.

I hold no brief for persons who seek to dominate the program and the progress of the Church. I do not believe in dictatorships of any kind, whether of bishops or boards, of pastors or presidents, of lay or ordained persons. It would be presumption of the worst sort for any one of us to assume that he or she could take over the powers of the Head of the Church. One thing is clear: we’re on a dead end street if we believe that’s the way to become empowered. The Church cannot grant power to persons. I want to say this again because you’re going to have to think very deeply at this moment The Church cannot grant power to people – that is, the kind of power Jesus was talking about, and the kind of power the Church must have to be the Church. The Church itself does not empower persons, it cannot empower ordained or unordained persons, laity or clergy, women or men, youth or age, white or nonwhite, rich or poor. The Church does not empower; only the Holy Spirit empowers.

The Church does, however, have the right and responsibility to grant authority to certain persons to speak and act in the name of the Church, in the pursuit of its witness in the world. The discipline of our church spells out these areas of authority and responsibility given to ordained and unordained persons, and we’re cautioned in Christian conscience to give a good account of our stewardship of this authority. However, at no point in the Discipline nor in the practice of the Church does the Church promise it can empower any one of us.

The power I speak of here, of course, is that power that Jesus promised would come – the power of redeeming, reconciling, recreating love. In relation to this power our lord affirms three great truths. First, He possesses it: “All power is given unto me.” Second, He promises it: “You will receive power.” Third, He provides it: “Lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.”

A bishop cannot increase a minister’s power by moving him or her to a larger parish. A person does not suddenly come into possession of this power when elected and consecrated a bishop. The opportunity to serve on some board or agency of the Church may give a person an enlarged opportunity to let the power of God flow through him or her in different and sometimes more creative channels. However, serving on boards and agencies of the church does not, in itself, grant a person spiritual power. Neither can spiritual power be gained by a struggle or a shrewd manipulation of the minds and wills of other persons for our own selfish ends. You will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes upon you. This is the pathway to power, the only pathway.

It should be clear to those who read the Scripture and study the experience of the Church that the Holy Spirit is a gift from the Father. Read those precious promises in the 14th, 15th and 16th Chapters of John’s Gospel, where Jesus speaks of the Holy Spirit’s coming. Let me just pick out phrases: “I will ask the Father and he will give you another to be your Advocate.” And then again He refers to the Holy Spirit “whom the Father will send In my name,” and still again, “when your Advocate is come whom I will send you from the Father,” and then again, “When he comes, who Is the Spirit of all truth.”

These are promises of a divine gift from the Father, not of something one earns, works for, deserves, or for whom ritual preconditions must be met. The Holy Spirit is a gift! The power of God is a gift! However, he must be received through faith; in confidence that He meant what he said, and He will do what he promised. That he initiates the offer of himself, that he stands at the door and knocks, that he will come in if we but open the door, that he will sup with us and we with him. Blessed, blessed promises, indeed!

The Holy Spirit comes as a gift from the Father and must be received through faith. Then he will abide in our hearts, and in the Church, and empower us and the Church as we obey Him. Jesus declared that the standard at the judgment would simply be “inasmuch as ye did it or did it not unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye did it or did it not unto me.” Here are both the personal and the social, the individual and the corporate, both the local and the world-wide implications of the Gospel. These have never been separated; they are dimensions of one Gospel, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all.

We see in this picture of Christ as the Head of the Church, not only preeminence and power but also his place in the unity of the believers. Paul emphasizes Christ’s headship of the Body, his Church, in his Colossian letter, and emphasizes the individual responsibilities of the various parts of the Body in his 1st Corinthian Letter, Chapter 12. Three things need to be said quickly about the different parts of the Body as this truth applies to the Churches. First, the parts of the body have different functions and different responsibilities. The hand can do many things the foot cannot do. The foot has individual responsibilities other parts of the body cannot perform.

So it is with the Church – not only with different persons of the Church but with different ministries and different congregations. The gifts of the Spirit differ. Some are given the gift of prophecy. Others have the gift of proclamation, others the gift of teaching, others a diversity of responsibilities. This we come to call “pluralism,” at least in some applications of the term.

However, the individual parts function only as they remain within the Body. In his Corinthian Letter, Paul emphasizes the fact that a body is not one single organ but many. And no single organ is the whole body.

No Christian has either the right or the authority simply to “do his own thing” without regard to what it means to the Body. Pluralism is one thing; polarization is another. The one cooperates toward a common goal and brings all the diversities together, making its own distinctive contribution toward that end. But polarization is divisive, hostile, and ultimately destructive.

This truth needs to dawn anew and afresh in our hearts this day, my dear friends. We need to pray for renewal of the sense of belonging to each other. Let us, in the name of God, cease this cold war that exists among us.

The Head is the center of unity for all the parts. For 2,000 years the Church has read and reread our Lord’s prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus prayed that they might all be one, even as God the Father, and Jesus Christ the Son are one. I do not speak here of organic union, even though I could do so without apology, for the United Methodist Church and its predecessors have long been in the forefront of discussions of organic union and actualizations of union. We’ll continue to dialogue with our Christian brothers and sisters in other denominations about these possibilities.

However, far more important than organic union is the unity we already have in Jesus Christ. No reshuffling of the structure can compensate for the rejection of that unity. No amount of mergers can substitute for unity in Christ. And I’m sure that those who are most committed to the ecumenical movement believe this as much as we do here tonight.

We need not unite in customs or cultures. The Church of Jesus Christ does not require its members to have political or philosophical sameness. No race has any right to attempt to swallow up another race or subordinate its culture. However, all of us who claim the name of Jesus Christ had better learn what it means to co~ together in the Spirit of Jesus Christ and work together under one banner of His redeeming love-and we’d better do it pretty soon or the forces of evil will destroy us before we know what’s happening to us. It is only “in Christ” that there’s no East nor West, no North nor South, no bond or free, no male or female. Equality is in him, unity is in him. And when any two of us come close enough to touch him, we’re close enough to touch each other. The saints have done it; God’s people can do it again.

Finally, it seems to me that Paul’s picture of Christ as the Head of the Church has to do not only with his preeminence, his power and his place as the center of unity, but also with His peace. Here the apostle is speaking about a cosmic Christ. Let me quote it again, “his is the primacy over all created things. Through Him God chose to reconcile the whole universe unto himself, making peace through the shedding of His blood upon the cross” {Colossians 1 :20}.

He charges us to be ministers of that peace and reconciliation. If you read II Corinthians in the New English Bible, you will read these words, “The love of Christ leaves us no choice.” He’s the author of peace in the inner life, for He brings the peace of God to dwell in us through faith. He’s the author of peace between persons by breaking down the middle wall of partition that we’ve allowed our selfishness to build. He’s the author of peace in our world through His lordship of all of life. It remains now for us to let him do his perfect work through us and through the Church, His Body!

by Steve | Aug 9, 1971 | Uncategorized

Christ’s Mighty Victory

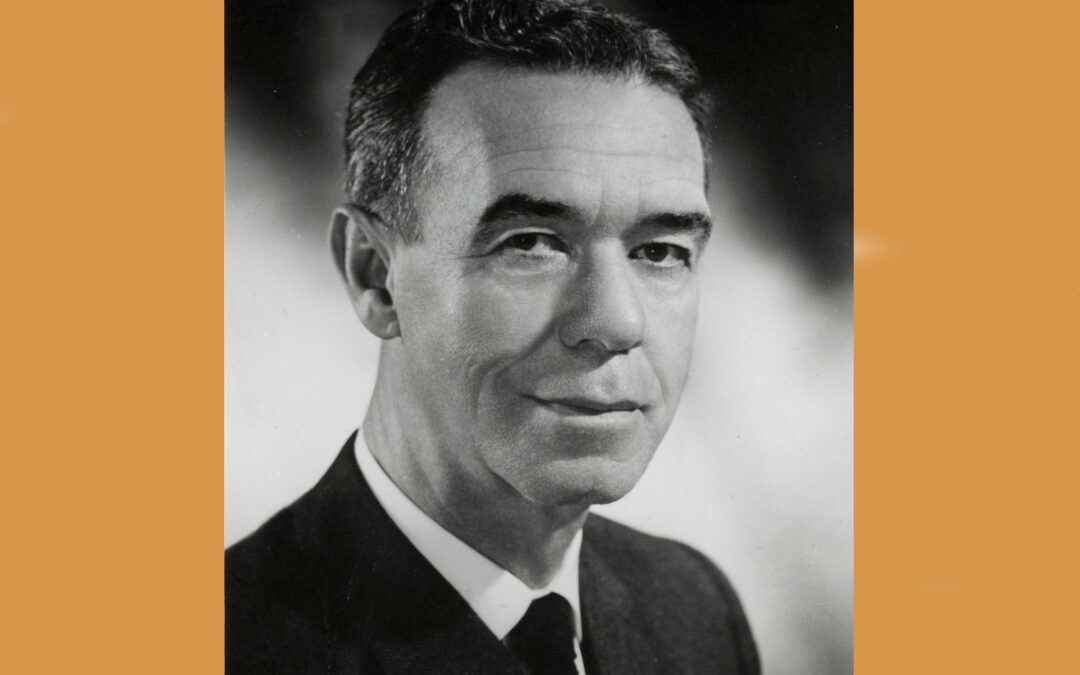

By Bishop Earl G. Hunt Jr.

Good News Convocation 1971

Business often carried a friend of mine through the plant of a great foundry. He never missed the opportunity to study the workmen who labored there. One man, a furnace-tender, always fascinated him. The bones and muscles of this laborer were those of a giant. His face was as strong as granite, and his hands as big as hams. It was a striking sight to see him work with his shovel and coal, huge muscles rippling in unbroken rhythm, face florid with heated blood, and pools of perspiration glistening on his bare skin as the glow from the furnace played across his body. He was rough, uncouth, a man of brawn more than of mind.

Once my friend saw him stagger, almost overcome with the intense heat of the fires. He looked weary, ill, nearly beaten. But he regained his footing, stepped aside into the cooler shadows, lifted his goggles, and passed a great blackened hand in gentle reverence over something hanging around his neck. It seemed to strengthen him. His strained features relaxed, and in a moment he was back on the job. Curious to know what had happened in that brief respite, my friend peered more closely and discovered that the something around the big workman’s neck was a tiny golden crucifix suspended on a short chain. It looked strange against its background of hot, damp flesh. But it did something for this giant of a man with his furnace and fires to have that tiny likeness of the Christ on the job with him. He could touch it and brush weariness aside. It was a fountain of refreshment and strength for him.

This incident helps to point up the nearly incredible power of that Strange Man who, as Ralph Waldo Emerson put it years ago, has “ploughed” his way into the “history of the world.” He and his mighty victory are the themes of New Testament Christianity, the roots of our religion. The tragic impoverishment of the Church’s witness in recent years is traceable to persistent ignoring, often in high places, of the naked spiritual power implicit in a full awareness of God’s work through Jesus Christ’s incarnation, death on the cross, and resurrection.

Dr. James S. Stewart (1896-1990) of the University of Edinburgh has reminded us that “the Christian religion is often today identified with pious ethical behavior and vague theistic belief, suffused with aesthetic emotionalism and a mild glow of humanitarian benevolence” (Thine is the Kingdom, 1956). It is simply impossible to account for the impact of the Christian faith in human experience and history apart from the Church’s ancient message of Jesus Christ and his mighty victory.

For example, we fail to understand St. Francis, whose saintliness casts a light even into the 20th century, if we do not see him as he kneels in the dilapidated Church of St. Damian outside the walls of Assisi and grasps for the first time the meaning of the Cross.

We glimpse the incentive that drove Horace Bushnell to bind the church and the home indissolubly together only when we visit the religious revival on Yale’s campus in 1831 and later, in 1848, spend the night with him as he responds to a radiant vision of Christ as the personal Revealer of God.

We look in vain for the secret of Walter Rauschenbusch, who stabbed the social conscience of Christendom awake in the days before World War I, until we find “the little pastern gate in the castle of his soul” and learn of the richness of his personal faith in the God revealed by Jesus Christ, which made prayer the dominant mood of his life.

Behind the deed forever stands the creed! As Christians, we act because God has already acted! To quote Stewart again, “The dynamic for our unaccomplished task is the accomplished deed of God” – or, put in the words of my theme tonight, Christ’s mighty victory. There are three imperishable acts of God that constitute the core of our Lord’s triumph.

- The Incarnation

“God was in Christ …” (II Corinthians 5:19a). How incongruous this assertion has seemed in recent years. One of the surprisingly prominent illusions of our era is that God is absent from his creation. As Professor William Hamilton has said: “We are not talking about the absence of the experience of God, but about the experience of the absence of God.” Put another way, radical theology says simply, but not freshly, “God is dead.” Zarathustra, Nietzsche, William Blake, Hegel – even Martin Luther – said it in earlier days. Bonhoeffer speaks in our modern day, and out of a deep devotion, about God “allowing Himself to be edged out of the world.”

The beginnings of this view are complex. Certainly it is an effort to interpret, in terms of faith, a weird age of the world’s history. It undertakes to account for secularism’s triumph. Fearing that the older theistic and theological views of life and history cannot survive contemporary international and cultural revolutions, it seeks to make a new and radically different road. It is secular theology, religionless Christianity, contrived to satisfy the empty realism of Julian Huxley’s “God-shaped blank in the modern mind.” But most of all, this illusion of illusions is based upon man’s arrogant metaphysical and actual independence of God. It rests upon the assumption that modern man can get along very well indeed without God.

What an illusion! A man prays and knows an answer. A Marine, dying in Vietnam, is told of the love that will not let him go, and peace and hope shine in his eyes. A great congregation sings with enthusiasm “A mighty fortress is my God” and the atmosphere of worship is charged with living power. A man who has just learned that he has an inoperable cancer receives Holy Communion and rises with quiet courage to take up his tasks for the time that remains. A member of Congress talks frankly with his pastor and then goes to the House floor to vote his Christian conviction, aware that the deed may cost him an election. A student kneels to pray at night, taunted by some of those with whom he lives.

God absent from his creation? What an illusion! Only those who have allowed philosophical hogwash to befuddle their brains and blind their eyes could possibly overlook the voluminous evidences to the contrary.

Or take yourself – you who don’t always believe in him, who think you operate your life with reasonable efficiency and effectiveness without him. Can you be honest enough to recall a moment when some alluring temptation to dishonor brought your soul to the edge of a precipice – and something held you back? Can you remember an hour dark with human need when suddenly light and help appeared? Or what about a memory that rose at nighttime to rebuke you or to bless you? Or a great and ennobling thought that broke unexpectedly across the barren terrain of your mind? Or some strange and exhilarating exultation after you had seen a great play or read a memorable book? Or the warm glow somewhere within you as you shared intimate fellowship with a dear and trusted friend? Or the sorrow of some bereavement? Or the ecstatic gladness of a beautiful surprise?

God absent from his creation? What an illusion! Do you remember how Isaiah pictures God saying to Cyrus the Persian, King of Babylon: “I girdeth thee, though thou hast not known me.”

The Death-of-God philosophy, never a serious threat to Christianity but rather an extreme manifestation of our age’s strange affinity for the novel and the bizarre, has moved now into an oblivion fashioned from its own internal irresponsibility and spiritual stupidity. The Incarnation, foundational doctrine of the Christian religion, reminds us again and afresh that God has betrothed himself forever to humanity!

God is not only not absent from his creation, he is forever identified with it. When the Everlasting God planned a nearer visit to earth, he chose the utterly human trails of a mother’s deep anguish and a baby’s low, helpless cry for the divine pilgrimage. He might have come as a heavenly visitant in trappings of cosmic splendor with spirit-legions and a chariot made of the winds, but this was not his way. He chose the cattle-shelter, ‘‘swaddling clothes,” and the loneliness of a man and a woman. And into this situation he came in the person of his son, Jesus. This is the first glory of the Incarnation.

Christianity begins with the most stupendous idea man’s mind has ever been asked to enfold: “No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, He hath declared Him” (John 1:18).

Here is what Swiss theologian Emil Brunner (1889-1966) said about that text: “This statement, which would make every good Platonist’s hair stand on end, is the central article in the Christian theory of knowledge.”

That the God of creation, infinite, holy, omnipotent, should care enough to identify himself with his creatures, putting on for a while the garments of flesh in order that he might understand us and we might know Him – this is history’s supreme fact. And its message of nearly incredible hope and joy is a light for life’s dark valleys and a song in its long nights. The God who made us has come to save us.

Do you remember G.K. Chesterton’s beautiful words?

“To an open house in the evening

Home shall men come,

To an older place than Eden

And a taller town than Rome;

To the end of the way of the wandering star,

To the things that cannot be and that are,

To the place where God was homeless

And all men are at home.”

John Wesley preached no recorded sermon on the Person of Christ. A distinguished student of his life declares that the founder of Methodism simply assumed the centrality of Christ’s position in the plan of salvation. If someone had asked him to prove the divinity of Christ, “he would probably have pointed to some humble convert, to some little band of men and women whose sins were forgiven and in whose faces shone that light which was reflected from the face of Christ.”

Years ago I heard the great Episcopal clergyman Joseph Fort Newton say of Jesus Christ, “He entered into the soul of humanity like a dye, the tinge of which no acid can remove.” And Robert Oppenheimer, in a reference to religion rare for his agnostic mind, commented upon the place of Jesus in the Christian philosophy with these words: “The best way to send an idea is to wrap it up in a person.”

These are authentic echoes of the chorus of the centuries in dealing with the great fact of the incarnation. If some of the early Christians came dangerously dose to forgetting his humanity, then some of us, in nearer days, have come dangerously close to ignoring his deity. Too often have we of a more liberal tradition surrendered the doctrine of the incarnation to those extremists of the faith who subscribe only to fundamentalism and bibliolatry.

The vital nerve of the Church’s mission at the crossroads of life will be severed if our generation is permitted to believe that the voice of Jesus Christ is no longer the voice of God. Kenneth Scott Latourette (1884-1968), the great historian of Christianity, said that the centuries reveal a direct relationship between the magnifying of the name of Jesus Christ and a revival of religious faith. But much more than this is true. The incarnation is the authentic authority for Christian involvement in seeking a solution to the tormenting social problems of this moment.

If we believe that God walked the dusty paths of this planet in the garb of flesh, we have no right to preach a disembodied gospel which scorns human needs, earthly problems and all mundane concerns. If Jesus Christ, indeed, was both man and God, then his gospel is the silken cord that binds earth and heaven forever together, and that urges the application of the heavenly insights in the Sermon on the Mount to such problems as racism, poverty, war, population control, ecology, moral confusion.

Here is the initial aspect of Christ’s mighty victory!

- The Crucifixion

Years ago I first read these words of Bishop William Fraser McDowell (1858-1937): “I would not cross the street to give India a new theology; India has more theology than it can understand. I would not cross the street to give China a new code of ethics; China has a vastly better code than ethical life. I would not cross the street to give Japan a new religious literature, for Japan has a better religious literature than religious life. But I would go around the world again and yet again, if it pleased God, to tell India, China and Japan and the rest of the world:

“There is a fountain filled with blood

Drawn from Immanuel’s veins,

And sinners plunged beneath that flood

lose all their guilty stains.”

The Cross, for me at least, is not ultimately subject to minute theological analysis. Men have seen many ideas in it – sacrifice, atonement, expiation, ransom, substitution, and propitiation – each with at least a modicum of truth to contribute to the whole.

The Cross is vastly bigger than the ideas men have had about it. It towers in magnificent mystery above Hugo Grotius and Anselm and Peter Abelard and all the others who have sought to reduce it to theories. Its message is beyond theological formulae. Emil Brunner comes as close as words may approach when he declares that we see three realities on Calvary: “The inviolable holiness of God; the absolute impossibility of overlooking man’s sin; and the illimitable mercy of God.”

In 1848, three Englishmen, all destined to become famous, were on a Paris holiday during the Revolution which overthrew King Louis Philippe. The men were Jowett, a future master of Balliol; Stanley, later Dean of Westminster; and Palgrave, a poet. Palgrave kept a diary and in it is an entry describing the sack of the Palace of the Tuileries by the mob. Everything was being smashed, when suddenly the mob reached the Chapel, broke in the doors, and found themselves staring at the huge painting of Christ crucified behind the altar. Someone called out, “Hats off!” Heads were bared, most of the crowd knelt down, and the picture was carried out to a neighboring church in utter silence.

This is the power of the Cross.

Years ago a Boston preacher set this couplet in my heart: “Christ, the Son of God, hath sent me o’er the widespread lands; Mine the mighty ordination of the pierced hands.”

The rugged, rigid disciplines of Christianity, by which the saints have been made, issue from an understanding of the Cross. Willingness to bear scorn courageously, to make sacrifice daily, to endure hardship and to face danger – these are the attributes of those who have taken a long look at Calvary.

Essential dedication will not-cannot-come to our generation of Christians without a fresh glimpse of the Cross. This is our message – not the dialectic of human philosophy – but Jesus Christ and him crucified, forgiveness of sin, redemption for lost and lonely mankind.

“Nothing in my hand I bring/ Simply to thy Cross I cling.” Here, again, is Christ’s mighty victory!

- The Resurrection

In the little book Interrupted By His Death, Albert Payson Terhune (1872-1942) wrote, “God always finishes his sentences.” The resurrection is the final, necessary clause of the sentence whose earlier parts have dealt with the incarnation and the crucifixion – the crescendo of Christ’s mighty victory. If the identity of Jesus Christ is our authority for the Christian enterprise and the redemption of the Cross is our message, then the resurrection is our hope and our triumph.

I know the resurrection has meaning at the point of abolishing the icy dread of death in the Christian’s heart. One great historian insists that the almost incredible accomplishments of the early Christians were due in large measure to their complete scorn of danger and death.

But I would have us think particularly of the resurrection as God’s ringing pledge of victory for his gospel’s cause and for those who labor in it. A great contemporary Christian thinker has said, ‘‘There had now appeared, in the midst of time, life in a new dimension … The early Christians were not merely preaching the resurrection as a fact; they were living in it as in a new country.”

In one of my pastorates there was a lovely and radiant young woman upon whose life heavy sufferings converged. Her husband was an alcoholic whose tragic condition defied the corrective efforts of successive ministers and a regiment of friends, and made him insensitive to the claims of responsibility, honor and love.

Debts rocketed, community derision for the man she loved cut her to the quick, financial duress kept her working though physically ill and decreed that she must not use her earnings for herself. But there was something memorably buoyant about her. She never lost hope. Others did for her, but not she. The commonest kindness, the tiniest scrap of good news became a harbinger of better things ahead in her perennially confident heart.

Each new morning was a magic scroll, a parchment of reverent optimism. Life was new and something marvelous might happen before nightfall! One day I had preached on “The Christian Hope” and her eyes danced in excitement as she thanked me for letting her hear a fresh utterance of the message God had given to her long before!

She died – all too soon, we thought – but with the banners of ecstatic expectancy flying yet over a debris of terrible heartaches. She was our lady of the resurrection hope. She used to make me think of Wordsworth’s lines: “My heart leaps up when I behold / A rainbow in the sky …. “ She was living Christ’s mighty victory!

Today’s headlines and telecasts have little of a hopeful nature to suggest about the coming of the Kingdom! The debilitating intrigues of continuing ideological struggles; the diabolically mad nuclear armament race still raging; the devastating revolution in morals – crime, sex perversion, drugs, alcohol; the generation gap; the lingering, senseless terror of the war in Vietnam; mind and behavior manipulation; genetic engineering; the ethical implications of organ transplants; racism of all colors; violence; lawlessness – and so it goes. But in the midst of all of this, the perceptive Christian senses a strange and wonderful wistfulness about our tragic moment in history. We begin to wonder with tremulous hope if the long tide is turning.

Dr. George Arthur Buttrick reminds us in one of his later works that the sea of faith has been ebbing for four centuries – we are the victims and not the authors of modern skepticism.

Another writes of our present day as an “age of longing.” Perhaps we are almost ready to doubt our doubts and to believe our beliefs again; perhaps we have discovered that our easy answers do not answer at all. Existentialism, in proper perspective, may help us to place our sense measurements of truth in a correctly subordinate position; for a true existentialist knows that a sailor’s knowledge of the weather is a deeper kind of knowing than that of the meteorologist, and that truth is to be found in the events of history rather than in the dialectics of the mind. We may be moving into a new age of faith.

There is a famous story of Faust gambling with his soul, about which an artist has painted a picture of a game of chess with Faust at one side and Satan at the other. In the picture the game is almost over Faust has left only a king, a knight and one or two pawns. He wears on his face a look of utter despair, while at the other side of the board the Devil leers in contemplation of his coming triumph. Many a chess player, looking at the picture, has agreed that the position is hopeless – a checkmate. But one day a master of the game stood in the picture gallery gazing at the scene. He was fascinated at Faust’s expression of utter despair. Then his gaze went to the pieces on the board and he stared at them absorbed as other people came and went. Then, suddenly, the gallery was startled by a ringing shout: “It is a lie! The king and the knight have another move!”

To us who are sons and daughters of the Resurrection faith, it is a parable of our situation. No matter how hopeless the times may seem to be, the King and the knight do have another move! This is the meaning of the Resurrection for the 20th century. And so hope surges again within us, moral muscles tighten, spiritual vision clears, and fear’s palpitations know a great calm. As someone has said, “We cannot be children of the resurrection and not see all the world bathed in resurrection light.”

The resurrection was the divine fiat that validated the facts and the philosophies of the incarnation and the cross. Someone said, “It is no epilogue to the Gospel, no codicil to the divine last will and testament, no appendix to the faith.” It is the triumphant concluding clause in God’s great sentence to man, and without it all that has gone before about the Incarnation and the crucifixion is but a weird jumble of words without meaning. Here is Christ’s mighty victory brought to tremendous and triumphant climax.

In my mind’s eye I see once more the big, brawny furnace-tender pausing in the heat of his task to pass his blackened hand in reverence over the golden crucifix which hung about his neck and receiving from this simple motion the strength and renewal needed to continue his work.

Religion is not just philosophy. When the human mind begins to develop its clever dialectics of God and man, sin and redemption, death and life, it is not necessarily dealing with the gospel. Sermons, even sermons, can prove to be exciting intellectual encounters with intriguing ideas, even ideas about the Bible, lofty philosophical monologues in which the holy, transforming presence of the living, loving, compassionate Lord is totally missing. There is no burning bush, no cry from Calvary, and there are rarely changed lives in the wake of such preaching.

No, the gospel is no dialectic of logic, no system of ethics, no musty set of morals, no book of platitudes. The Gospel is love’s aching arms when life is lonely and barren. The gospel is inconceivable forgiveness when sin has been bleak and persistent. The gospel is hope when hope is long gone, dawning’s bright fingers clutching at the throat of night. The gospel is life when death has done its hideous worst. The gospel is the everlasting light of Christ’s mighty victory in the Incarnation, on the cross and in the resurrection. This – and only this – is the foundation for our message about both personal and social religion. Let us proclaim it with new confidence!

Earl G. Hunt was a United Methodist bishop in North Carolina.

by Steve | Jun 14, 1971 | Uncategorized

Archive: Jesus, Teacher and Lord

By John R. Stott

July/September 1971

I have been helped by some words Jesus spoke in the upper room just after He had washed the apostles’ feet. When he had resumed his place, he said to them: “You call me Teacher and Lord; and you are right, for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet.”

‘Teacher’ and ‘Lord’ were polite forms of address used in conversation with rabbis. And the apostles used them in addressing Jesus. What he was now saying is that in his case they were more than courtesy titles; they expressed a fundamental reality. As the New English Bible renders it: ‘You call me Teacher and Lord, and rightly so, for that is what I am.’ I am in fact, he declared, what you call me in title.

This verse tells us something of great importance both about Christ and about Christians.

What it tells us about Christ concerns his divine self-consciousness. Though but a peasant from Galilee, carpenter by trade and preacher by vocation, he claimed to be the Teacher and the Lord of men. He said he had authority over them to tell them what to believe and to do. It is evident (if indirect) claim to deity, for no mere man can ever exercise lordship over other men’s minds and wills. Moreover, in advancing his claim he showed no sign of mental unbalance. On the contrary, he had just risen from supper, girded himself with a towel, poured water into a basin, got on his hands and knees, and washed their feet. He who said he was their Teacher and Lord humbled himself to be their Servant. It is this paradoxical combination of lordship and service, authority and humility, lofty claims and lowly conduct, which constitutes the strongest evidence that (in John’s words in this passage) ‘he had come from God and was going to God’ (John 13:3).

Secondly, the same verse reveals the proper relationship of Christians to Christ. This is not only that of a sinner to his Savior, but also of a pupil to his Teacher and of a servant to his Lord. Indeed, these things belong indissolubly together. He is ‘our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.’ What, then, are the implications of acknowledging Jesus as Teacher and Lord?

Of course everybody agrees that Jesus of Nazareth was a great teacher, and many are prepared to go at least as far as Nicodemus and call Him ‘a Teacher come from God.’ Further, it is clear that one of the most striking characteristics of his teaching was the authority with which he gave it. He did not hem and haw and hesitate. Nor did he ever speak tentatively, diffidently, apologetically. No. He knew what he wanted to say, and he said it with quiet, simple dogmatism. It is this that impressed people so much. As they listened to him, we read, “they were astonished at his teaching, for his word was with authority.’’

There is only one logical deduction from these things. If the Jesus who thus taught with authority was the Son of God made flesh, we must bow to his authority and accept his teaching. We must allow our opinions to be moulded by his opinions, our views to be conditioned by his views. And this includes His uncomfortable and unfashionable teaching … like his view of God as a supreme, spiritual, personal, powerful Being, the Creator, Controller, Father and King, and of man as a created being, made in the image of God but now fallen, with a heart so corrupt as to be the source of all the evil things he thinks, says and does …. He taught the divine origin, supreme authority and complete sufficiency of Scripture as God’s Word written, whose primary purpose is to direct the sinner to his Savior in order to find life. He also taught the fact of divine judgment as a process of sifting which begins in this life and is settled at death. He confirmed that the final destinies of men are the awful alternatives of Heaven and Hell, adding that these destinies are irrevocable, with a great gulf fixed between them.

These traditional Christian truths are being called in question today. The independent, personal, transcendent being of God, the radical sinfulness of man, the inspiration and authority of Scripture, the solemn, eternal realities of Heaven and Hell – all this (and more) is being not only questioned, but in many places actually abandoned. Our simple contention is that no man can jettison such plain Gospel truths as these and still call Jesus “Teacher.”

There have been other religious teachers, even if less authoritative than Jesus. But Jesus went further, claiming also to be Lord. A teacher will instruct his pupils. He may even plead with them to follow his teaching. He cannot command assent, however, still less obedience. Yet this prerogative was exercised by Jesus as Lord. “If you love me,” He said, “you will keep my commandments.’’ “He who loves father or mother … son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me.’’ He asked from his disciples nothing less than their supreme love and loyalty.

So Christians look to Jesus Christ as both their Teacher and their Lord – their Teacher to instruct them and their Lord to command them. We are proud to be more than his pupils; we are his servants as well. We recognize his right to lay upon us duties and obligations: “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet.’’ This ‘ought’ we accept from the authority of Jesus. We desire not only to submit our minds to his teaching but our wills to his obedience. And this is what he expected: “Truly, truly, I say to you, a servant [literally ‘slave’] is not greater than his master.’’ He therefore calls us to adopt his standards, which are totally at variance with the world’s, and to measure greatness in terms, not of success but of service; not of self-aggrandizement, but of self-sacrifice.

Because we are fallen and proud human beings, we find this part of Christian discipleship very difficult. We like to have our own opinions (especially if they are different from everybody else’s) and to air them rather pompously in conversation. We also like to live our own lives, set our own standards and go our own way. In brief, we like to be our own master, our own teacher and word.

People sometimes defend this position by saying that it would be impossible – and if it were possible it would be wrong – to surrender our independence of thought. Drummer Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones expressed this view when he said: “I’m against any form of organized thought. I’m against … organized religion like the Church. I don’t see how you can organize 10,000,000 minds to believe one thing.” This is the mood of the day, both in the world and in the Church. It is a self-assertive and anti-authoritarian mood. It is not prepared either to believe or do anything simply because some “authority” requires it. But what if that authority is Christ’s? What if Christ’s authority is God’s? What then? The only Christian answer is that we submit, humbly, gladly, and with the full consent of our mind and will.

But do we? Is this, in fact, our regular practice?

It is quite easy to put ourselves to the test. What is our authority for believing what we believe and doing what we do? Is it, in reality, what we think and what we want? Or is it what Professor So-and-so has written, what Bishop Such-and-such has said? Or is it what Jesus Christ has made known, either himself directly or through his apostles?

We may not particularly like what he taught about God and man, Scripture and salvation, worship and morality, duty and destiny, Heaven and Hell. But are we daring to prefer our own opinions and standards to his, and still call ourselves Christian? Or are we presuming to say that he did not know what he was talking about; that he was a weak and fallible Teacher, or even accommodated himself to the views of his contemporaries although he knew them to be mistaken? Such suggestions are dreadfully derogatory to the honor of the Son of God.

Of course we have a responsibility to grapple with Christ’s teaching, its perplexities and problems, endeavoring to understand it and to relate it to our own situation. But ultimately the question before the Church can be simply stated: is Jesus Christ Lord, or not? And if he is Lord, is he Lord of all? The Lordship of Jesus must be allowed to extend over every part of those who have confessed that “Jesus is Lord,” including their minds and their wills. Why should these be exempt from his otherwise universal dominion? No one is truly converted who is not intellectually and morally converted. No one is intellectually converted if he has not submitted his mind to the mind of the Lord Christ, nor morally converted if he has not submitted his will to the will of the Lord Christ.

Further, such submission is not bondage but freedom. Or rather, it is that kind of willing Christian bondage which is perfect Christian freedom – freedom from the vagaries of self and from the fashions of the world (and of the Church), freedom from the shifting sands of subjectivity, freedom to exercise our minds and our wills as God intended them to be exercised, not in rebellion against him, but in submission to him.

I do not hesitate to say that Jesus Christ is looking for men and women in the Church of this kind and caliber today, who will take him seriously as their Teacher and Lord – not just paying lipservice to these titles (“Why do you call me ‘Lord, Lord,’ and not do what I tell you?”), but actually taking his yoke upon them, in order to learn from him and to “take every thought captive to obey Christ.”

This will involve for us, first, a greater diligence in study. We can neither believe nor obey Jesus Christ if we do not know what he taught. One of the most urgent needs of the contemporary Church is a far closer acquaintance with Scripture among ordinary members. How lovingly the pupil should cherish the teaching of such a Master!

It will also involve a greater humility in subordination. By nature we hate authority and we love independence. We think it a great thing to have an independent judgment and manifest an independent spirit. And so it is, if by this we mean that we do not wish to be sheep who follow the crowd, or reeds shaken by the winds of public opinion. But independence from Jesus Christ is not a virtue; it is a sin, and indeed a grievous sin in one who professes to be a Christian. The Christian is not at liberty to disagree with Christ or to disobey Christ. On the contrary, his great concern is to conform both his mind and his life to Christ’s teaching.

And the reasonableness of this Christian subordination lies in the identity of the Teacher. If Jesus of Nazareth were a mere man, it would be ludicrous thus to submit our minds and our wills to him. But because He is the Son of God, it is ludicrous not to do so. Rather, submission to him is just Christian common sense and duty.

I believe that Jesus Christ is addressing the Church of our day with the same words: “You call me Teacher and Lord; and you are right, for so I am.” My prayer is that, having listened to his words, we shall not be content with the use of these courtesy titles, but give him due honor by our humble belief and wholehearted obedience.

By John R. Stott (1921-2011). In addition to being Rector of All Souls Church in London, Dr. Stott was considered one of the foremost evangelical thinkers and theologians in modern time. Condensed by permission of InterVarsity Press, from his book, “Christ, The Controversialist.” This article was republished by permission in the July/September 1971 issue of Good News.

by Steve | Nov 10, 1967 | Uncategorized

Methodist Heritage: The Place of Evangelicals in the Methodist Church Today

Bishop Gerald Kennedy (1907-1980)

Good News, Winter 1967

The main difficulty in writing on this subject is finding a definition acceptable to the majority of Methodists. Finding two people who will agree precisely as to what “evangelical” means is difficult. I must therefore state in a broad way how I intend to use the term – but with the warning that it is impossible to be too precise and that any description must have uncertain borders.

What is it? Since the Reformation, the term “evangelical” has been applied to Protestant churches which based their teaching pre-eminently on the Gospel as defined in the Bible. There was usually a difference between these evangelical churches and the Calvinist bodies, although the precise difference was never very clear.

Within the broad framework of the Church of England, the evangelicals put their emphasis on personal conversion, the atoning death of Christ, and salvation by faith. They came to be a particular party within the Church of England in a day when the general condition of the clergy was low. Methodism, in the beginning, had very much in common with the evangelical group. John Fletcher of Madeley was one of the evangelical leaders and also one of Methodism’s early heroes. The evangelicals, for the most part, were marked with a deep seriousness. And sometimes they were regarded as being too religious. In the nineteenth century they took a leading part in social reform, and in missionary activity.

Theologically, evangelicals have commonly upheld the verbal inspiration of the Scriptures and have regarded the Bible as the sole authority of the Church. They have believed in preaching as of supreme importance and they have had a tendency to minimize liturgical worship. They have been suspicious of Roman Catholic and high church doctrines.

In our time, evangelicals would be regarded as more conservative in their theology than many Methodists. Very often they support a doctrine of the second coming, the virgin birth, and the conversion experience as an essential for every Christian. Some of them would shade off into the fundamentalist camp, I expect, and take a dim view of the critical study of the Bible. Their vocabulary is often archaic to some modern ears. And their insistence upon more precise definitions of the doctrines a Christian must believe to be truly a Christian, are stumbling blocks to many who have moved into the more liberal, modern atmosphere.

The Demands of the Church. But let us agree that an exact definition is impossible. I have met with some of these people who became Methodists via the Nazarene Church, and I have found them in such accredited seminaries as Fuller in Pasadena. Often they have a warmth of spirit and a conviction of belief that lifts up my heart. Sometimes their affirmations are not congenial to me now, and they take me back to my boyhood and to my father’s faith. It must be said that there is no question in my mind as to their being a legitimate part of the Methodist heritage. They are Wesleyan in their basic propositions. Their emphasis on conversion finds an echo on nearly every page of John Wesley’s Journal. The truth seems to me to be that The Methodist Church has been, broadly speaking, evangelical in its understanding and interpretation from the beginning.

In Los Angeles we have had two groups looking at each other suspiciously for a long time. One has been the evangelical churches and the other has been the so-called mainline denominations such as the Methodists, the Presbyterians, United Church of Christ, and the American Baptists. One of the reasons I was glad to become the chairman of the Billy Graham Campaign in 1963 was that it provided an opportunity to bring these two groups closer together. We never succeeded in eliminating all our differences, but we did make progress in talking to one another and trying to listen to each other with some appreciation. I was struck with the obstacle of vocabulary as well as with fundamental differences in our attitudes toward Biblical criticism, evolution, and the place of the Church in the world. But I was even more impressed with our broad base of commonly accepted doctrine. And I was hopeful for a continuing dialogue which, it seemed to me, would enrich both parties. That is the main reason I am glad to accept an invitation to write on the place of evangelicals in The Methodist Church.

For one thing, I must say that it is rather shocking that this question would be raised by anybody in The Methodist Church. It is even more shocking to observe that some of those who have been most outspoken in favor of the ecumenical movement seem to be most unsympathetic with anybody disagreeing with them in The Methodist Church. We might as well come to terms with the reality that no church is in any position to make an ecumenical contribution if it cannot find room within itself for honest men with differing beliefs.

The Right Spirit. I am convinced that the main obstacle which faces us is not our differences, but the spirit in which we hold them. I have known some fundamentalists so narrow and bitter that it was impossible to talk with them. It seemed to me that they were full of pride in their righteousness and they belonged with the Pharisees rather than with the Christians.

On the other hand, I have known any number of men whose theological positions seemed to me quite impossible, but who were my Christian brothers and dear friends. We could talk together and share with one another our convictions in a spirit of love and mutual respect.

It is true also, of course, that I have known liberals who were so dogmatic and unbending that they could put the fundamentalists to shame. Even when I agreed with most of what they had to say, I could not feel at ease with them because of this bitter, partisan spirit. It was either their interpretation or none. So I conclude that there will be room in The Methodist Church for men of very widely differing theological points of view only if their spirits are open and loving.

This, of course, is one of the most difficult things in the world to achieve. It is hard for a man with a great conviction to believe that a man who differs with him is honest. But this is one of the miracles which Christ works for us and we ought to pray that He will touch us with His grace. I know it can happen because it has transformed my relationships with other people more than once. A Christian experience goes straight to the heart. And then, although we do not find complete unity in our heads, it really does not matter too much. Methodism must remember that John Wesley said this very often. This is one of his principles upon which we stand or fall.

One of my friends is a theological professor who retired some years ago. His theological position seemed to me very far to the left and oftentimes appeared to me little more than humanism. On the other hand, my position seemed to him hopelessly far to the right. Sometimes in our conversations together I would say to him, “How in the world can such a nice fellow have such lousy theology?” His reply would be, “How can a fellow who is smart enough to fool the Church into electing him a bishop be so reactionary?” Through all these past years we have been close friends, and I would no more think of trying to put him out of the Church than I would think of attacking the saints. The greatness of Methodism has been its freedom and its discipline. My brother, if your heart is with my heart, give me your hand.

We Need Each Other. Let us look at this a little further. Instead of stopping here, let us move on to the affirmative truth which shines through this question. We need each other. Instead of merely putting up with somebody who is different than we are, let us thank God that He gives us an authentic witness from the other side of the hill. I am not very happy with some of the proposed new approaches of our day. Much of it sounds shallow, and I am sure in my own mind that much of it is of passing interest only. Yet I am on the side of any group who feel so strongly about the relevancy of the Church that they want to find ways to make it speak to the world. I will fight to the last ditch for their right to experiment. Even when they fail, their efforts have still been worthwhile, in my judgment. There is a fellow (not a Methodist) who has been putting on a night club act in San Francisco. He is trying to read from a book he wrote and bear a Christian witness. I wish him luck, although my own experience in trying to talk religion to people with four or five drinks under their belts has not been very encouraging. But I will take him any day over the Methodist preacher I dealt with some time ago who wanted to close his church and move out because there were saloons in the neighborhood.

On the other hand, I am strong for the brethren whose emphasis is on the unchanging and eternal verities of our faith. We should be in a bad way indeed if we become like the Athenians described in the Book of Acts as those who “spent their time in nothing except telling or hearing something new” (Acts 17:21). I believe in the Bible and I believe in conversion. I believe that Methodism made a great difference in eighteenth century England, and I believe it ought to be making a great difference in twentieth century America. The evangelicals keep the unchangeables before us and it is something which we must not forget or consider unimportant.

I am convinced that The Methodist Church cannot afford to lose the evangelicals. It would be a sad day indeed if they should feel unwelcome and go somewhere else. They are just as legitimately Methodists as are any of these brethren who look down their noses at them and consider them outmoded.

A great deal of this modern spirit is a passing thing, and after we have changed our minds a hundred times in the future, the great and fundamental truths of our religion will shine forth with continuing brilliance. With all the modern talk about the Church having to keep up to date, it is great to have clear voices proclaiming that over against all the novelties there is the unchanging truth of what God has done for us through the Incarnation.

The Ecumenical Challenge. There is a new wind blowing in the mulberry trees in our time. I doubt if any single man or single party can interpret the meaning of it completely. We have seen a miracle take place in the world with the Second Vatican Council. We can talk with each other and we can learn from each other in a way that was not possible just a few years ago. What the outcome of this is to be I do not know – and I do not think anyone else does. However, one thing does seem rather clear to me: if the ecumenical spirit means anything, it must begin to work between conflicting points of view within a single church. I welcome our evangelical brethren within Methodism not because I want to be a nice fellow, but because I need them. As a Methodist, I do not think I have any other choice. If they will put up with me, I surely will put up with them. Not only that, but I will sit at their feet that together we may learn of a new devotion and a new commitment which is much more needed in Methodism than a new method.

This is going to take more grace than most of us possess at the present time. But if we pray for this gift from God, and if we are willing to receive it, the first step will have been taken in the renewal of the Church.

As I grow older I experience increasing doubts of my ability to grasp very much of the truth or Christ. I need as many different witnesses as possible to keep me aware of my own poverty and of the unsearchable riches of Christ.

Gerald Kennedy was the Bishop of the Los Angeles Area of the Methodist Church.

by Steve | Nov 9, 1967 | Uncategorized

A Death to ponder

Editorial by Charles Keysor

November/December 1976

Death often leads us to ponder, to reflect upon the earthly life and labors of one now departed. We remember what he or she has accomplished between the terminal points of birth and death. We consider how the world may be different because of this one particular life.

On July 30 this year, Rudolf Karl Bultmann died in Marburg, West Germany. He was 71 years old.

Probably Bultmann was the greatest theological giant of our times. Alongside him in the pantheon of the central 20th century theology, would be Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, and Reinhold Neibuhr. But Bultmann’s influence was surely the greatest. There is little doubt it will be the longest-lasting, for the disciples of Rudolf Bultmann permeated theological education in the Western World. They transmitted Bultmann’s thinking to several generations of highly influential church leaders preachers, teachers in colleges and seminaries, writers, editors, bureaucrats, and bishops.

Rudolf Bultmann was deep and complex, to say the least. That he was a great mind, none can question. But what matters is not so much his massive intellect as the presuppositions he held concerning ultimate realities.

“It is no longer possible for anyone seriously to hold the New Testament view of the world,” Bultmann declared. “In fact, there is no one who does.”

Christianity Today, in an editorial commenting on his death, offered this cogent summary: “His presuppositions began with a conscious rejection of theological orthodoxy. [He] did not allow for the presence of a personal, transcendent God who acts decisively and historically to redeem His people and who speaks in an intelligible manner to reveal Himself and His ways to men and women. He excluded the supernatural by definition from his system, as also any real intervention of the living God into the affairs of the world. Therefore [for Bultmann] the concept of miracle was ruled out, including the greatest miracle of all, the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ …. ”

“Wedding his theology to the existentialist philosophy of the early Martin Heidegger, Bultmann assumed the most radical tradition of Biblical criticism. He denied the historicity of all but a few basics of the life of Jesus (the “thatness”) and essentially dismissed the Old Testament and all Jewish elements in the Bible as irrelevant for Christian theology.”

This statement is accurate. It correctly describes Bultmann’s philosophical life-blood, and so it helps us to understand better his powerful influence on three generations of seminary professors and students.

“The tragedy of his influence and the painful burden it bequeathed to us stems from a good intention and a much-needed corrective gone amiss,” explains Rev. Dr. Paul Mickey, Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology, Duke Divinity School, and Chairman of the Good News Task Force on Theology. “His was a concern for the sofa fides principle, salvation by faith alone. This was nobly lifted up by Martin Luther during the Protestant reformation.”

As a Lutheran himself, Bultmann was eager to reaffirm this principle in opposition to 19th century liberalism. He correctly perceived the need to reaffirm that salvation is sofa fides, by faith alone. But he went too far. He jumped on a ‘faith bandwagon’ and rode off into existential psychologism, away from history.”

Here is where heresy enters Bultmann’s work, the Duke professor said. “For Bultmann, atonement [i.e., the death of Christ on the cross in payment for our sins] was reduced to ‘self-understanding’ and history was pushed aside. The same principles which whisked away the historicity of the Bible also made history irrelevant for the modern believer.”

What is our faith apart from its history? A cross that may have happened, if you choose to believe this. A tomb that was really empty only to those who make it so by believing that “He lives!” A record of early church growth and witness which may be only propaganda that was concocted to sell Christianity as a miracle religion.

If the Bible record of events is not reliable, then those who trust it are really fools and simpletons — as Bultmannians sometimes suggest.

Time Magazine for October 19, 1976, reported a major archaeological find at ancient Ebia in Syria — a large number of clay tablets dating between 2400 and 2250 B.C. Describing the first discovery, Time reflected the wide spread assumption that Biblical events and places are really not historical: ” … it [the discovery] also provides the best evidence to date that some of the people described in the Old Testament actually existed ….

“The Biblical connections appear to be numerous. The tablets contain accounts of the creation and the flood, which are strikingly similar to those found in both the Old Testament and Babylonian literature. They refer to a place called Urusalima, which scholars say is clearly Ebla’s name for Jerusalem. (If so, it is unquestionably the earliest known reference to the Holy City, predating others by hundreds of years.)

“We always thought of ancestors like Eber as symbolic,” says [ David Noel Freedman, a University of Michigan archaeologist who worked in the excavations], “at least until these tablets were found. Fundamentalists could have a field day with this one.”

Such is the common assumption: Biblical places, people, and events probably did not actually exist. Bultmann has done more than any other, in our time, to increase this distrust in the Bible’s historicity.

“If history is at best irrelevant theologically,” Dr. Mickey observed, “if not untrue, then the atonement, the idea of God as Creator and the notion that we have social responsibilities in obedience to God — all these are lost and gone forever! Bultmann’s heresy was not his affirmation of sola fides, but his exclusivism which rejected history and good works.”

Everything was reduced to subjectivism, or to purely personal judgment and opinion, Dr. Mickey said. Under Bultmann’s thinking, there was “no need or power for good works and a lively social witness. Without history there is no social order.

“Thus the epithet, ‘Faith without history and good works is dead heresy’ may be the final judgment of Christian history on Professor Bultmann.”

Rudolf Bultmann tore the very heart out of Biblical Christianity, and this same characteristic is widely evident in our church today. Shortly after Bultmann’s death, a tribute was given by Dr. F. Thomas Trotter, staff executive for the UM Board of Higher Education and Ministry (in charge of our colleges and seminaries). UM Communications circulated a story about this tribute. It reported that Dr. Trotter had said that the church, if it is to survive and compel the attention of modern persons, will need theologians like Bultmann. Why? To keep the church thinking about its mission and its gospel, Dr. Trotter declared. He also observed that Bultmann’s legacy to the church is his care for the authority of the Word of God, spoken in modern situations and in speech direct enough that the personal meaning will not be missed.

“Such scholar-prophets [as Bultmann] will have their detractors and they will risk our displeasure,” Trotter confessed. “But what they have to say to us is this: if our language is archaic, our response to the Gospel is merely formal, and our preaching is vacuous, then the power of God’s possibilities for men and women will be absent from the world.”

“The world does not require so much to be informed as reminded,” Hannah Smith once said. The church is reminded, upon the death of Rudolf Bultmann, that men die in a few swift years, but the truth of God survives. In Eternity, when a final accounting is made, belief will be judged more enduring than doubt. That is why Paul wrote to young Timothy: “The time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching cars they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own likings, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander into myths” (II Timothy 4:3, 4). N

by Steve | Jun 1, 1967 | Uncategorized

Archive: The Character of a Methodist

June 1967

By John Wesley

Few Methodists today are aware that Methodism’s founder wrote a profound definition of the Methodist character. We have preserved the ideas of Wesley but tried to express them in 20th century language. -Charles W. Keysor, Editor

The distinguishing marks of a Methodist are not his opinions of any sort … his accepting this or that scheme of religion … his embracing any particular set of notions … or mouthing the judgements of one man or another. All these are quite wide of the point.

Therefore, whoever imagines that a Methodist is a man of such and such opinion is sadly ignorant. We do believe that “all Scripture is given by inspiration of God.” This distinguishes us from all non-Christians. We believe that the written Word of God is the only and sufficient rule both of Christian faith and practice in our lives. And this distinguishes us from the Roman Catholic Church.

We believe that Christ is the eternal, supreme God. This distinguishes us from those who consider Jesus Christ to be less than divine.

But as to all opinions which do not strike at the root of Christianity, we think and let think. This means that whether or not these secondary opinions are right or wrong, they are NOT the distinguishing marks of a Methodist.

Neither are words or phrases of any sort. For our religion does not depend on any peculiar way of speaking. We do not rely upon any quaint or uncommon expressions. The most obvious, easy words which convey the truth most effectively — these we Methodists prefer, in daily speech and when we speak about the things of God. We never depart from the most common, ordinary way of speaking — unless it be to express Scriptural truths in the words of Scripture. And we don’t suppose any Christian will condemn us for this!

We don’t put on airs by repeating certain Scriptural expressions — unless these are used by the inspired writers themselves.

Our religion does not consist of doing only those things which God has not forbidden. It is not a matter of our clothes or the way we walk; whether our heads are covered; or in abstaining from marriage or from food and drink. (All these things can be good if they are received gratefully and used reverently as blessings given to us by God.) Nobody who knows the truth will try to identify a Methodist by any of these outward appearances.

Nor is a Methodist identified because he bases his religion on any particular part of God’s truth. By “salvation,” the Methodist means holiness of heart and life. This springs from true faith, and nothing else. Can even a nominal Christian deny this?

This concept of faith does not mean we are declaring God’s Law to be void through faith. God forbid such a perverted conclusion! Instead, we Methodists believe that faith is the means by which God’s Law is established.

There are too many people who make a religion out of 1) doing no harm, or 2) doing good. (And often these two together.) God knows, we Methodists do not fall into this mistaken way of defining our Christianity! Experience proves that many people struggle vainly for a long, long time with this false idea of religion consisting of good works (or no bad works)! In the end, these deluded people have no religion at all; they are no better off than when they started!

THEN WHAT IS THE DISTINGUISHING MARK OF A METHODIST? WHO IS A METHODIST?

A Methodist is a person who has the love of God in his heart. This is a gift of God’s Holy Spirit. And the same Spirit causes a Methodist to love the Lord his God with all his heart, with all his soul, with all his mind, with all his strength.

God is the joy of a Methodist’s heart; the desire of his soul, which cries out constantly, “Whom have I in heaven but You, Lord?” There is nothing on earth that I desire but You, my God and my All! You are the strength of my life. You, Lord, are all that I need.”

Naturally the Methodist is happy in God. Yes, he is always happy because the Methodist has within him that “well of water” which Christ promised. It floods up to overflowing, bringing glorious assurance of the life that never ends. Therefore, the Methodist is a person in whom God’s peace and joy are constantly evident.

The Methodist does not fear God’s wrath for himself. Perfect love has banished fear of God’s punishment from the Meth odist’s heart. For this reason, he is able to rejoice evermore. He does not rejoice in himself or in his achievements. Instead the Methodist rejoices in God, who is his Lord and his Savior.

The Methodist acknowledges God as his Father. Why? Because the Methodist has received from Jesus Christ the power to become a glad and grateful son of the Father.

The Methodist is one who realizes that He belongs to God instead of satan. This is redemption. It is possible only because Jesus gave His life on the cross. He shed His blood to make atonement for the sins of all who believe in Him. The Methodist trusts in Christ alone for his salvation. The Methodist knows that the blood of Jesus has cleansed him from all sin. Through Christ and Christ alone the Methodist has received forgiveness for his sins.

The Methodist never forgets this. And the Methodist shudders as he considers the eternal punishment from which he has been delivered by Jesus Christ. The Methodist gives thanks that God loved him enough to spare him — to blot out his transgressions and iniquities … to atone for them with the shed blood and broken body of His beloved Son.

Having personally experienced deliverance from God’s wrath, the Methodist cannot help rejoicing. He rejoices every time he thinks of his narrow escape from eternal destruction. He rejoices that by God’s kindness he, a sinner, has been placed in a new and right relationship with his Creator. This miracle has been accomplished through Jesus Christ, the Methodist’s beloved Savior.

Whoever thus believes experiences the assurance of God’s love and forgiveness. This clear and certain inner recognition is witness that the Methodist is a son of God by faith. This truth is made known to the Methodist as God sends His own Spirit to bear witness deep within the mind and soul of the Methodist, enabling him to cry out “Father, My Father!” This is the inner witness of God’s Holy Spirit, testifying to the Methodist of his adoption into God’s own family.

The Methodist rejoices because he looks forward confidently to seeing the glory of Christ fully revealed one day. This expectation is a source of great joy, and the Methodist exalts, “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! According to the Father’s abundant mercy He has caused me to be re-born so I can enjoy this eternal hope which never fades or tarnishes. This is an inheritance of faith. It cannot be stolen, lost, or destroyed in any way. It is a pure and permanent hope. God has reserved its fulfillment in eternity for me!”

Having this great hope, the Methodist gives thanks to God at all times, and in all circumstances. For the Methodist knows that God expects His children to be always grateful.

The Methodist receives every happening cheerfully, declaring “Good is the will of the Lord.” Whether the Lord gives or takes away, the Methodist blesses the name of the Lord.

Another characteristic of the Methodist: he has learned to be content, whether he has much or little. When humiliation comes, the Methodist accepts this gladly as the Father’s will. When prosperity and good fortune come, the Methodist likewise gives God the credit. The Methodist accepts all circumstances gladly, knowing that these are God’s doing, intended for his ultimate good.

Whether he is in leisure or suffering pain … whether he is sick or in good health … whether he lives or dies, the Methodist gives thanks to God from the very depths of his heart. For the Methodist trusts that God’s ways are always good … that every wonderful and perfect gift comes to us from God, into whose providential hand the Methodist has committed his body and soul.

The Methodist knows no paralyzing frustration and anxiety! For the Methodist has thankfully cast his every care upon God, never failing to let God know all about his needs and problems.

The Methodist never stops praying. It is second nature for him to pray and not to be discouraged. This does NOT mean that the Methodist is always praying in a church building! (Though it goes without saying that the Methodist misses no opportunity for public worship.) The Methodist is often on his knees in humility before God, but he does not spend all his time in contemplation.

Nor does the Methodist try to beat God’s ears with many words. For the Holy Spirit speaks to God on behalf of the Methodist, expressing his innermost hopes and longings which human words cannot articulate. This alone is true prayer; the language of the heart which overflows with joy, sometimes is best expressed in holy silence before God.