by Steve | Mar 17, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March/April 2020

By Frank H. Billman –

Martin Edi Ori (right) conducts the choir at Macedonia United Methodist Church in Yapo-Kpa, Côte d’Ivoire. Photo by Mike

DuBose, UMNS.

What date would you choose for the birthdate of Methodism? The General Conference of the Methodist Church of England met in 1837 and a committee of preachers and laymen was assembled to put together a celebration of the Centennial, the first hundred years of Methodism. But the first question that they had to settle was what date should they use for the beginning of Methodism? Someone suggested that they use the date of Wesley’s ordination, but that was not supported.

Do you know what other famous date was not supported? May 24, 1738, Wesley’s Aldersgate Street experience. That was an obviously famous and important date in Wesley’s life. Although it was a pivotal milestone, the Holy Spirit had been moving in his life before that time. Dr. Scott Kisker, Associate Professor of Church History at United Theological Seminary, has commented that if Aldersgate was all that Wesley had, he would have probably retired as an Anglican priest at Epworth with his heart strangely warmed and we would never have heard of him or Methodism.

The fact of the matter is, Charles Wesley had his heart warming experience two days before John’s. And George Whitefield had one even before that. And there were others at the time, Anglicans and non-Anglicans, who were having heart-warming experiences.

The Rev. Doug Fox, senior pastor of First United Methodist Church of Irving, Texas, and a DMin student in Supernatural Ministry at United Theological Seminary, read through Wesley’s Journal from May 24, 1738 through the end of that year, a seven-month period. He was especially looking for changes in Wesley’s life and ministry as a result of his Aldersgate experience. Fox found that there was little positive change. Wesley’s Journal entries in those seven months were filled with doubt and questions. He wrote of periods of spiritual exaltation and acute spiritual depression equal in severity to anything preceding the Aldersgate experience. There are at least eleven depression entries, starting the day after the Aldersgate experience. And there are only two clear supernatural occurrences that he records during that time.

Wesley was still restricting his preaching to inside church buildings and there were no huge crowds. He made a pilgrimage to Hernhutt for an extended visit at the Moravian headquarters, but nothing spiritually earth shattering happened in Wesley’s life or ministry during those seven months after Aldersgate.

So, what date did the General Conference of 1837 come up with as the date for the start of Methodism? In his Journal, John Wesley writes on Monday, January 1, 1739, the New Year’s Day after his Aldersgate Street experience with the Moravians, John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield and about 60 others gathered at a Watchnight meeting at Fetter Lane. Wesley wrote, “about three in the morning, as we were continuing instant in prayer, the power of God came mightily upon us insomuch that many cried out for exceeding joy, and many fell to the ground.”

Twenty-four year old George Whitefield, who was present at this meeting wrote, “It was a Pentecostal season indeed … we were filled as with new wine … overwhelmed with the Divine Presence….” Writing in 1861, Methodist historian Abel Stevens referred to this incident as their baptism in the Holy Spirit. It is clear that this was an infusion of spiriutal power within Methodism and this was the date that General Conference of 1837 used to date the beginning of Methodism.

Four days later George Whitefield met with seven other despised Methodists who left the meeting with a full conviction that God was about to do great things among them. It was in that year that Whitefield “broke the ice,” as he says, by beginning outdoor preaching in England. He then led Wesley to do the same thing.

In his research, Fox also read through Wesley’s Journal for the seven months after Fetter Lane. He found one entry about spiritual depression on January 4, 1739 and then no others. Furthermore, in the seven months following Fetter Lane, Wesley records in his Journal no less than 31 supernatural occurrences involving whole crowds of people.

It is “safer” for us to look back at Wesley’s Aldersgate experience as the beginning of Methodism. It was a private experience. It was a salvation experience or at least an assurance of salvation experience. Even non-Methodists have no problem with someone having a “heart-warming experience.” But the Methodists at the one hundred year mark were still greatly in touch with the fact that Methodism began with a “messy” outpouring of the Holy Spirit where over sixty Anglicans were all over the floor crying out due to the tangible presence of God in the room with them.

Methodism began with what Abel Stevens referred to as a baptism of the Holy Spirit experience that a group of people shared together like on the day of Pentecost. After this powerful experience at Fetter Lane, the lives and ministries of those people changed dramatically.

Perhaps we should ask God for a fresh infilling of the Holy Spirit like the Wesleys and their friends experienced that New Year’s Day in 1739.

Frank Billman is a United Methodist clergyperson, the DMin Mentor in Supernatural Ministry at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio, and an adjunct Faculty Member at the Bishop John G. Innis Graduate School of Theology at the United Methodist University in Monrovia, Liberia.

![The Cross]()

by Steve | Mar 17, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March/April 2020

By Steve Beard –

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.

“On a hill far away, stood an old rugged cross,” we sang. “The emblem of suffering and shame / And I love that old cross where the Dearest and Best / For a world of lost sinners was slain.”

Modern day hipsters may roll their eyes at the sentimental lyrics, but they stuck with me. It was a sing-a-long song about the most brutal injustice in human history and it became a well-known gospel chorus for an entire generation. Johnny Cash recorded four different versions. It was also recorded by Al Green, Ella Fitzgerald, Merle Haggard, Mahalia Jackson, Patsy Cline, Willie Nelson, and Loretta Lynn.

“The Old Rugged Cross” was written in 1913 by a Methodist preacher named George Bennard (1873-1958) who was converted to faith as a young man after walking five miles to a Salvation Army meeting. At age 15, he had lost his father in a mining accident. Bennard found new life and inspiration in giving his heart to a Savior riddled with nail scars who had conquered death.

“The crucifixion is the touchstone of Christian authenticity, the unique feature by which everything else, including the resurrection, is given its true significance,” writes the Rev. Fleming Rutledge in her magisterial book, The Crucifixion. “Without the cross at the center of the Christian proclamation, the Jesus story can be treated as just another story about a charismatic spiritual figure. It is the crucifixion that marks out Christianity as something definitively different in the history of religion. It is in the crucifixion that the nature of God is truly revealed. Since the resurrection is God’s mighty transhistorical Yes to the historically crucified Son, we can assert that the crucifixion is the most important historical event that has ever happened.”

When my father would serve communion at our United Methodist church, he said: “The body of Christ, broken for you. Feed on him in your heart by faith with thanksgiving.” Those words can still bring tears to my eyes. Sundays come and Sundays go, but those words stick in my soul. The Lamb of God was betrayed by a sleazy friend, ambushed by a well-armed battalion, falsely accused by conniving religious leaders, condemned by a spineless politician, and publicly executed before his weeping mother as cries of ridicule filled the air and birds of prey circled overhead.

To the abused who feels shame, this Crucified Christ stands with empathy. To the wrongly accused, this Crucified Christ stands with the truth. To all those victimized by injustice, this Crucified Christ stands with the innocent. “Come to me, all you who are weary … and I will give you rest,” Jesus said.

There are countless examples of contemporary Christian leaders who fail to live up to the Jesus ideal. Unfortunately, that has been the failed track record of Church history. But the Christ who was humiliated and shivved in the side on Golgatha is the genuine article. I try to keep my eyes on him. In every conceivable way, Jesus is counterintuitive. Who would have ever come up with a game plan of forgiving your enemies, turning the other cheek, and loving those who plot your demise?

“Even the excruciating pain could not silence his repeated entreaties: ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’ The soldiers gambled for his clothes,” wrote the late Anglican scholar, the Rev. Dr. John R.W. Stott. “Meanwhile, the rulers sneered at him, shouting: ‘He saved others, but he can’t save himself!’ Their words, spoken as an insult, were the literal truth. He could not save himself and others simultaneously. He chose to sacrifice himself in order to save the world.”

I understand the reluctance to spend inordinate time dwelling on the sufferings of Christ. It’s macabre and grotesque. It is the stigma of the story, the stain, the moment you turn your head away. But it is an inescapable part of redemption’s drama.

For those in the modern era, it is hard to imagine a time when crosses weren’t sold as bedazzled necklaces, home décor accessories, or garish t-shirt designs (“Body Piercing Saved My Life”). The cross was not always viewed as an icon for a faith dedicated to a kingdom that was not of this world. “To the early Christians it was a symbol of disgrace. They could not look upon it as an object of reverence,” wrote historian George Willard Benson. “Death by crucifixion was the most shameful and ignominious that could be devised. That Christ should have been put to death, as were debased and despised criminals, was bitterly humiliating to his followers.”

Over the centuries since Christ’s blood-soaked public execution, the cross was slowly transformed from a symbol of shame and humiliation to one of victory and triumph for all of us who have been shamed and humiliated.

In his critically acclaimed book, Dominion: How The Christian Revolution Remade the World, British scholar Tom Holland points out that the tales of a human-divine hybrid were not unfamiliar in ancient history. Mythology from Egypt and Greece and Rome featured heroic monster-slayers and a pantheon of warlords that claimed to be empowered from the heavens.

“Divinity, then, was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings,” writes Holland. “Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself: to nail them to the rocks of a mountain, or to turn them into spiders, or to blind and crucify them after conquering the world. That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque.”

The gospel is upside-down storytelling. Perhaps it helps explain the inexplicable allure of Jesus. The story does not end on a towering cross on the edge of town where the dying moan and mothers weep. More was to unfold.

Osiris, Zeus, and Odin are worshipped no longer. The Savior of the widow and orphan and tax collector is still worshipped around the globe. That is not chest-puffing triumphalism; it is simple reality. “The crucifixion of Jesus, to all those many millions who worship him as the Son of the Lord God, the Creator of heaven and earth, was not merely an event in history, but the very pivot around which the cosmos turns,” writes Holland.

Holland only returned to the church of his childhood while writing his book. His thinking was dramatically affected while filming near a battlefront in an Iraqi town where Islamic State fighters had previously used crucifixion as a means of terror. “For the first time, I was facing the reality of crucifixion as it had been practiced by the Romans, face to face,” he told the Church Times. “It was physical in the air … people had been crucified by people who wanted the effect of crucifixions to be that which the Romans had wanted. They wanted to generate the sense of dread and terror and intimidation deep in the gut, and I felt that….

“I realized how important it was to me to believe that, in some way, someone being tortured on the cross illustrated the truth of the possibility that power might be vanquished by powerlessness, and that the weak might vanquish the strong, and that … hope might be found in the teeth of life in despair.”

Perhaps the hope found in the horror of the cross of Christ is the “assertion that the same God who made the world lived in the world and passed through the grave and gate of death,” wrote novelist Dorothy Sayers. Explain that to an unbeliever, and “they may not believe it; but at least they may realize that here is something that a man might be glad to believe.”

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Opposite page art work is a section of the stained glass work in the chapel of the Orange County Rescue Mission designed by Peter Brandes.

by Steve | Mar 17, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March/April 2020

By Thomas Lambrecht –

The recently announced separation plan called the “Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace Through Separation” has aroused many reactions in and beyond the church. Some are satisfied and even hopeful that the long-running conflict in our church can finally be over and traditional and evangelical United Methodists will be free to pursue ministry without being hampered by discord or a dysfunctional denominational structure. Local churches will get to keep their buildings, property, and assets and will need to make no extra payments to move into the new traditionalist Methodist denomination.

Others are upset and angry over provisions of the agreement they believe are unfair. We have heard the criticisms of the plan. We understand them. Many of them are legitimate. Clearly, there are several unfair provisions.

The most common criticism I have heard of the agreement is that traditionalists are leaving The United Methodist Church, rather than it being an equal separation. The follow-up comment is that since traditionalists “won” the vote in the St. Louis special General Conference in 2019, it should be those who want to change the church who have to leave and start a new denomination, not those who want to maintain the current doctrine and discipline of the church.

This is a perfectly valid point. In an ideal and just world, those who want to change the church’s understanding of marriage and ordination would leave and those who want to keep the church’s long-standing teachings could remain. Unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect or just world.

This agreement did not come down from God on Mt. Sinai like the Ten Commandments. It is a negotiated agreement worked out between factions in the church that deeply disagree with one another and do not trust one another. Separation within The United Methodist Church has taken place over the last several decades; it has been brewing under the surface. The fact that there is an agreement at all is astounding and a testament to the dedication of the participants and the perseverance of the mediator.

In negotiated settlements, it is not what is right or fair that determines the outcome, but what is possible. This agreement is the best possible agreement that could be reached and is preferable to all other likely alternatives.

What happened in 2019? At the 2019 General Conference, traditionalists made a good-faith effort to bring about unity in the church through compliance with the Book of Discipline, the governing document of the church. It maintained the current teaching and standards of the church, while attempting to increase accountability of bishops and clergy to live by those standards.

Since February 2019, it has become readily apparent that this attempt at unity through compliance did not work. More than half the annual conferences in the U.S. declared their opposition to the provisions enacted in the Traditional Plan. A number of annual conferences and bishops have declared that they will not abide by the provisions of the Discipline. The Greater New Jersey Annual Conference is even trying to write its own Book of Discipline!

This widespread disarray indicates that the church cannot achieve unity through compliance. The gate-keepers on enforcing the Discipline are the bishops. If some bishops are unwilling to enforce the Discipline and plan to simply ignore its requirements, there is nothing the larger church can do about it. The accountability process for bishops envisioned in the Traditional Plan was ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Council. The accountability process proposed by Bishop Scott Jones and others that relies upon the Council of Bishops to hold other bishops accountable depends upon having a majority of the Council willing to exercise that accountability. At this point, and into the foreseeable future, the majority of the Council favors changing the church’s requirements and will decline to hold colleague bishops accountable.

Since unity through compliance is not possible, and unity through allowing for “local option” (each annual conference and local church making its own rules about marriage and ordination) does not have the votes to pass General Conference, the only apparent way to resolve the conflict is some form of separation. The recent agreement recognizes this fact and provides a way for the church to go in two different directions. We should not discount the fact that, for the first time, some of our leading bishops and other church leaders have finally acknowledged that separation is the only viable way forward for the church.

How to Separate. The fairest way to separate would be to dissolve The United Methodist Church and create two or more new denominations with new names. Such an approach is unworkable because it requires changes to the constitution, which needs a two-thirds vote at General Conference and a two-thirds vote of all the annual conference members (which could take up to two years). Most self-described centrists and progressives are against dissolving the church, as are many Africans and Europeans. Dissolving the church and starting over would most likely not reach even a majority vote, let alone the two-thirds vote required.

So any form of separation that General Conference adopts will have to have a continuing United Methodist Church and a group or groups that form something new. The closest to an equal plan of separation under this precondition is the Indianapolis Plan. However, that plan did not resolve the contentious issue of a division of assets. Furthermore, it encountered fierce opposition from key leaders in the centrist camp, who believe it comes too close to dissolving the denomination. To pass the Indianapolis Plan would require a major fight at General Conference, which could degenerate into a repeat of the vitriol of St. Louis. And its passage is by no means certain, as the margin for traditionalists is projected to be very slim.

The leaders of the Renewal and Reform Coalition decided that it would be better to support a plan that is less fair, but promised a definitive end to the conflict, was much more certain to pass, and would give traditionalists a way to separate while keeping their buildings and property.

Throughout the last year, many progressives and centrists have vowed not to leave the church, but to stay and continue to fight to change the church’s teachings and standards. It is true that a few very progressive annual conferences and a few high-profile progressive leaders have announced plans to prepare to possibly leave the denomination. But the vast majority would stay, and the fight would continue. It is therefore unrealistic to hope that most centrists and progressives would voluntarily leave the church. No matter what good legislation General Conference adopts, if there is no way to obtain compliance, the Discipline is not worth the paper it is written on. Any attempt on traditionalists’ part to keep on fighting for the current teachings of the church would entail another 20 years of conflict, rebellion, disobedience, and vitriol that would destroy the church.

If we were to fight to hang on to The United Methodist Church, traditionalists would also be saddled with trying to either maintain or reform an intractable bureaucracy that is often counterproductive to local church ministry. Every single general board or agency except United Methodist Communications endorsed the One Church Plan. Most of those boards and agencies are staffed by people who want to change the church’s teachings and do not share our traditional theological perspective. To reform and reclaim these agencies would be a monumental task that would again drain valuable resources from actual ministry. If we can drastically lower overhead in a new denomination, we can pour more resources into supporting our central conferences outside the U.S. and engaging in innovative, effective ministry to the unchurched and marginalized people in our world.

What about the money? Faced with the possibility of an impending split in the denomination, United Methodists are rightly worried about the financial impact of the separation plan. Giving to the denomination’s general apportionments fell immediately after the special St. Louis General Conference last February. A number of annual conferences are struggling to meet their budgets. The General Council on Finance and Administration has proposed an 18 percent cut to the quadrennial budget for 2021-24.

Many clergy, particularly retired clergy, are worried about their pension. The good news is that all the proposed plans of separation have made provision for continuing clergy pensions at the current level. Wespath has developed plans and legislative language that would allow clergy in any new Methodist denomination to continue participating in the clergy pension program. Earned benefits would continue at the same level as previously expected. Unfunded pension liabilities would be allocated between the post-separation United Methodist Church and the new Methodist denomination(s), with no payments for these liabilities required. The only exception to the continuation of pensions at the current level would be for congregations and clergy who go independent and do not align with a new Methodist denomination.

Financial Support for New Methodist Denominations

One of the aspects of the newly proposed Protocol agreement for separation that appears unfair is the allocation of $25 million to a new traditionalist Methodist denomination that forms and $2 million to any other new Methodist denominations that might form. Progressives complain that a denomination they believe unjustly discriminates against LGBTQ people should not receive any money upon separation. Traditionalists believe that the amount of money is just a drop in the bucket compared to the total assets of the general church.

It is important to note that the Protocol agreement is the only proposal that came to any agreement about the amount of funding for the new Methodist denomination(s). Where did the $25 million come from? Here is how that calculation was arrived at. According to the General Council on Finance and Administration, total assets held by the general church and its agencies amounts to over $1.536 billion dollars. But about half of that amount, over $753 million, is owed to others as liabilities. That leaves net assets of about $783 million. Of that amount, about $204 million is in buildings, property, and other fixed assets. Donor restricted assets total about $460 million. That leaves about $120 million in unrestricted assets that would be available for any kind of division of assets. (It proved unrealistic to expect to share in the proceeds of any buildings or property that might never be sold, and the mediation group did not want to cause the sale of buildings or properties. The legal complications that would be involved in trying to divide restricted assets proved to be too much to overcome, taking those assets off the table.)

The negotiation resulted in one-third of the $120 million being allocated for the new Methodist denomination(s), about $40 million. $2 million was set aside for potential other denominations that might form, while $38 million was set aside for a traditionalist denomination. Traditionalists agreed to forego one-third of their share ($13 million) to give it to fund ethnic ministry plans and Africa University. (The post-separation United Methodist Church agreed to set aside double that amount for the same purpose, $26 million, leading to a total of $39 million for ethnic ministry and Africa University. This represents continuing the current level of funding over the next eight years.) The goal with the ethnic minority funding is to ensure that some of the most vulnerable populations in our church are not harmed by the separation.

The $25 million that is left will be paid to the new traditionalist Methodist denomination over the four years 2021-24 in equal installments.

Apportionments. The General Council on Finance and Administration is looking at the possible impact on apportionments of a separation. It is undeniable that a significant loss of members and churches from the post-separation United Methodist Church would cause a decline in funding available to the general church agencies and programs. Since it is hard to forecast how many churches might separate, it is difficult for GCFA to budget for apportionments for the next quadrennium. The post-separation United Methodist Church will need to make adjustments to programs and denominational structure in order to account for reduced financial resources available.

By contrast, the new Methodist denomination(s) forming from this separation will be able to start with low overhead. For example, in its draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline, The Wesleyan Covenant Association envisions fewer and smaller agencies, capitalizing on partnerships with existing ministries. This would allow the denomination to care for essential functions, while preserving the ability to respond nimbly to changing needs of congregations and cultural circumstances.

A new future. Talking about money is difficult. Money is often a symbol of our values, hopes, dreams, beliefs, and power. Many traditionalist observers have voiced concerns that the amount of funding given to the new denomination upon separation is not commensurate with the resources that contemporary traditionalists and prior generations have contributed to the church over the decades. As legitimate as these concerns may be, the negotiated settlement was conceived in good faith based on the calculations and limitations shared above.

It is understandable for some to see it as though traditionalists will be “leaving” The United Methodist Church. A better way of describing it is that traditionalists will be separating from a denomination that has left them theologically and seizing this opportunity to create a new traditionalist Methodist movement. No, this agreement is not as fair to traditionalists as we hoped it would be. But it promises a definitive end to the conflict in our denomination and provides an unparalleled opportunity for a fresh start that can create a new denomination that can go forward in unity of belief, vision, and mission.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Mar 17, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March/April 2020

By Chris Ritter –

The opening of the 2019 United Methodist General Conference in St. Louis. Photo by Kathleen Barry, UM News.

There is good reason to believe that the United Methodist Separation Protocol will be approved early at the 2020 General Conference and today’s United Methodist denomination will give way to two separate churches, each different from anything we have previously known. While it is possible additional options may surface, I believe most congregations and conferences will choose between one of two oxymorons: A New Traditional Methodist Church and a Post-Separation United Methodist Church. We will all take part in fleshing out what these curious descriptions will ultimately mean.

There is ample evidence accumulated over the years about the shape of a United Methodist Church no longer frustrated with organized Traditionalist interference. The Post-Separation UM Church in America aspires to be connected globally but governed separately as a U.S. mainline denomination. It will be open, permissive, and institutional. It will embrace theological pluralism on a scale the UM Church never could and will take the quest for social justice and diversity as its unifying paradigm.

There are things that I would love about continuing to serve in the institutional UM Church. But my First Love calls me alongside those who will begin figuring out what “new traditional” means. Glimpses of the future have surfaced here and there, including the draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline offered by the Wesleyan Covenant Association. But more voices must come to the table to give this task the justice it deserves. What we shall be has not yet been revealed. For now I can only share my hopes.

I hope the new church is all about Jesus: His lordship, his gospel, his message, his cross, his resurrection, his transforming power, and his coming kingdom. I hope it is never about anything else. I hope we proclaim the Jesus prophesied in the Old Testament, revealed in the New Testament, and proclaimed in the classic creeds.

I hope we are charismatic in the highest and best definition of that word. I hope the Holy Spirit fills us with a fresh Pentecost so that our gospel consists not only in words but in power. I hope our sons and daughters prophesy and our seasoned saints continue to dream dreams.

I hope we are a praying church, not just a church that prays. I hope we are a worthy of the great heritage of prayer left to us by folks like Susannah Wesley, E. Stanley Jones, and E.M. Bounds.

I hope we always find ourselves in humble awe as we gather at the table of the Lord. I hope we never lose the joy and calling of our baptism. I hope we worship deeply, richly, joyfully, and sacrificially.

I hope we are a singing and song-writing church. I hope Charles Wesley and Fanny Crosby smile down from Heaven on a whole generation of artists inspired by and inspiring the work of God happening around them.

I hope we confess our sins to one another and hold one another accountable in love. I hope we recover small groups such as bands, class meetings, and other forms of intentional discipleship. I hope we break free of the gravity of shallow consumer Christianity.

I hope we are global. I hope we are African, European, Asian, and North American. I hope autonomous churches in Puerto Rico, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Pacific Islands, and South America help us comprise something completely new. I hope elements of Evangelical British Methodism will find their way to a place of close fellowship.

I hope we are conspicuously multi-ethnic here in the U.S. I hope it happens inevitably as we lift up Jesus together. I hope the new traditional church is a home for African Americans, Koreans, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders, and newer immigrants communities coming to the U.S. I hope we creatively conference together so as to maximize our impact in diverse communities and prosper our collective witness.

I hope there is no Board of Missions because the whole church is mission. I hope there is no Board of Evangelism because the whole church is evangelism. I hope there is no Social Witness Board because the church itself is the living embodiment of social holiness.

I hope the church embraces education and life-long learning. I hope we have the best minds in Wesleyan theological scholarship and do not make a golden calf of institutional education as the sum of the preparation needed by our clergy.

I hope we have a strong “culture of call” and that the clergy union gives way to pure servant leadership. I hope the best and the brightest of our young people answer Jesus by giving themselves away in ministry. I hope our current gifted young evangelical clergy are filled with holy boldness to lead.

I hope we produce pastors from shift workers, Ivy League faculties, the recovery community, second career people, and former prostitutes.

I hope we are the church of bishops who are apostolic shepherds, prophetic and scholarly with missionary hearts. We need bishops who are truth-tellers and ministry strategists. I hope all our bishops maintain laser-like focus on equipping healthy local churches to aim them outward toward their communities.

I hope local pastors and bi-vocational pastors are fully recognized and empowered for ministry. I hope the hard categories of laity and clergy become more and more blurred as we are all in ministry together.

I hope we plant three new churches a day to make up for the losses we have experienced since we planted two a day in a different era. I hope we are worthy heirs in evangelism to Phoebe Palmer, Harry Denman, Francis Asbury, Martin Boehm, and Peter Cartwright.

I hope our conference meetings are like revivals. I hope our iron sharpens iron. I hope we quickly abandon habits that do not produce fruit. I hope we fast and lay prostrate before the Lord when we don’t know what to do. I hope matters of structure and strategy are always kept as secondary concerns.

I hope the Methodist social witness will find a fresh flowering as we give voice and flesh to Wesleyan faith and practice in the larger marketplace of ideas and values.

I hope we repent when we mess things up. I hope we never hit the snooze button when the Holy Spirit tries to awaken us to new opportunities. I hope we resist the trappings and comfort of nationalism. I hope prophetic voices are not kept out in the wilderness.

I hope our large church pastors are honored as ministry pioneers and not looked upon with suspicion. I hope micro and mega churches alike successfully reproduce healthy DNA in new locations.

I hope we sell what we have and give to the poor. I hope we adopt and foster kids who need a home. I hope warm-hearted pro-life beliefs are matched with practical assistance to those who are struggling. I hope we welcome the sojourner and stranger. I hope we are a place of welcome and healing for the broken, the outcast, and the afflicted.

And I hope we engage more deeply with the LGBTQ community. I hope we stop arguing over what we believe and begin serious missiological reflection and action based on those beliefs. I hope the battered and broken refugees of the sexual revolution find a home with us.

I hope we don’t react so strongly against what was wrong with the UM Church that we lose what was right. I hope we don’t try so hard to prove what we are not that we miss claiming who God is calling us now to be. I hope we don’t succumb to the temptation of replacing all the comfortable structures we are leaving behind.

I hope we can forgive and bless our brothers and sisters in the post-separation UM Church so they, too, can move forward with their own hopes and dreams. To borrow from President Abraham Lincoln, who said in a different historical context, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right…”

As we are the ones that will be separating, I hope we leave well – and not look back. And I hope we begin well, too. It is time to build and that’s kind of exciting.

Chris Ritter is the directing Pastor of Geneseo First United Methodist Church in Illinois and the author of Seven Things John Wesley Expected Us to do for Kids (Abingdon 2016). This article first appeared on Dr. Ritter’s blog peopleneedjesus.net.

![The Cross]()

by Steve | Mar 17, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March/April 2020

By David F. Watson –

“Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by a Heap of Gold,” Tempera on panel painting by the Master of the Osservanza Triptych, ca. 1435, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikipedia Commons.

Several years ago a student stopped me in the seminary hallway. “Brother, will you pray for me?” he asked. “I’m under spiritual attack.”

I now look back on that day with regret. I didn’t take him seriously. I said something to appease him and went on my way. Spiritual attack? Well… okay… sure. I’ll pray for you. I wish I had laid hands on him, prayed in that moment, and continued in prayer for him thereafter. Indeed, this student was under spiritual attack. At the time, however, I didn’t have the theological framework to take seriously what he was asking.

In short, I blew it, and I should have known better. After all, I’d spent the previous ten years working on the Gospel of Mark.

Plundering Satan’s house. Mark is very clear about the purpose of Jesus’ ministry: he has come to defeat Satan. In chapter 3, the scribes accuse Jesus of performing his great deeds by the power of Satan. “He has Beelzebul,” they say, “and by the ruler of the demons he casts out demons” (3:22). “Beelzebul” was originally a Philistine deity (derived from Baal), which Jews associated with Satan. Jesus points out the obvious flaw in their argument: “How can Satan cast out Satan? If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand. And if a house is divided against itself, that house will not be able to stand. And if Satan has risen up against himself and is divided, he cannot stand, but his end has come (3:23-26).” In other words, he asks, why would someone empowered by Satan cast out Satan’s minions? To use a modern idiom, why would Satan shoot himself in the foot?

Jesus then describes his own work as follows: “No one can enter a strong man’s house and plunder his property without first tying up the strong man; then indeed the house can be plundered” (3:27). Jesus has come to plunder what Satan – the “strong man” – has taken. The work of Jesus’ ministry is effectively to bind up Satan and his demons, and then to recover the lives that Satan has claimed. This will happen first by exorcism, healing, teaching, and the gathering of a movement around him. The ultimate victory, however, will come through the cross and resurrection. From start to finish, Jesus’ ministry involves tying up the strong man and plundering his house.

Cosmic powers of this present darkness. Scripture teaches us that Jesus has dealt Satan a death blow, but Satan continues to fight in the lead up to his inevitable demise. Our reality, then, is one of spiritual warfare. Mainline Protestants don’t talk very much about spiritual warfare. It has to it the ring of words that belong to a Christian dialect not quite our own. Yet if the mission of the church is a continuation of the mission of Jesus, then spiritual warfare should be a part of our life. Like Jesus, we are engaged in a battle with the spiritual forces of wickedness. The Letter to the Ephesians is quite clear about this: “Our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (6:12). There are spiritual realities, says Paul, that lie behind the evil that we encounter in this world.

This is the reality disclosed to us in the Revelation to John. Yes, John inists, there are forces in this world that oppose the kingdom of God, but behind their worldly power lies another power. The two beasts in Revelation 13 allude to the Roman Empire and the imperial cult. They seem overwhelmingly powerful. “Who is like the beast, and who can fight against it?” (13:4). Yet the power they exert against the church is not their own. It comes from the dragon, whom John identifies as Satan (12:9; 13:2,4). They draw upon a transcendent reality, the “cosmic powers of this present darkness,” “spiritual forces of evil in heavenly places.”

Those same powers are at work today, only in different guises. There are Romes beyond Rome. There are idols beyond the emperor and his cult. We cannot defeat these in our own strength. To win a spiritual battle, we must use spiritual weapons. The people of God have always faced enticements to idolatry. We will do so until Christ returns. The names and faces of our idols may change, but the power behind them does not.

The “immanent frame.” Over time, we in the West have largely lost sight of the fact that there is a transcendent world that comes to bear on our lives. Philosopher Charles Taylor describes the modern Western perspective as the “immanent frame.” This is a very complex idea, but, to summarize briefly, Taylor argues that our primary means of engaging the world today is one of “immanence,” rather than “transcendence.” Put more simply, we function on the basis of what we can see and touch. We understand ourselves and the world around us as something we make. We don’t really see ourselves as being under the influence of spiritual beings. Instead, we emphasize our own skill and understanding.

Moreover, Taylor argues, we might actually be quite religious and still function according to the immanent frame. In other words, we might profess belief in supernatural powers, and we might even believe we believe these things. Yet our basic decisions are not affected by them. We go about our days with expectations and decisions that take no account of what might be happening in a spiritual realm. The beliefs we profess have not sunk deeply enough into our thinking to have any real power in our lives. If we really want to move beyond the immanent frame, we have to retrain our minds.

Biblical scholar Michael S. Heiser talks in his book The Unseen Realm (Lexham Press, 2015) about the importance of reading biblical texts as if the transcendent realities they disclose are actually true. Speaking personally, he writes, “The realization that I needed to read the Bible like a premodern person who embraced the supernatural, unseen world has illumined its content more than anything else in my academic life.” One of the key principles for biblical interpretation that Heiser suggests is, “Let the Bible be what it is, and be open to the notion that what is says about the unseen realm might just be real.”

I would take things a step further. We should not only be open to the notion that what the Bible says about the unseen realm is real, but actively imagine our own lives in light of the supernatural reality the Bible portrays. For a good part of my life, I read the biblical texts not with an attitude of overt rejection of its supernatural worldview, but simply with a kind of unconscious detachment from the cosmos it envisions. Angels? Demons? Satan? Sure… I supposed they were real, but my world was really within an immanent frame. These concepts did no heavy lifting for me. My expectations were almost entirely this-worldly. As I began to imagine an unseen realm coming to bear on my life, however, my expectations began to change. I began to see the goings-on in my life from a different perspective.

Discernment matters. Of course it is possible to take the idea of spiritual warfare too far. We need not abandon our critical faculties as we begin to take seriously the spiritual realities of the unseen realm. Our problem may not be unbelief or a lack of expectation, but an unreasoned fanaticism. Have you ever known someone for whom it seemed like everything happened because of the devil? Sometimes the reasons for things are quite mundane. If I forget to set my alarm and miss a meeting, it’s probably because I was careless, distracted, or tired, rather than because of some spiritual attack. To be wise in spiritual matters is to exercise discernment, a trait that comes from spiritual maturity. Spiritual maturity, in turn, comes from a life of prayer, accountability to other believers, receiving the sacrament, and engagement with other means of grace. As we grow up in our faith we become more discerning with regard to the spiritual goings-on around us.

The weapons of our warfare. In Ephesians 6:10-17, Paul describes what we must do in order to “stand firm” on behalf of Christ. In speaking of the “whole armor of God,” he draws upon military imagery to speak of spiritual realities. “Stand therefore, and fasten the belt of truth around your waist, and put on the breastplate of righteousness. As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace. With all of these, take the shield of faith, with which you will be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.” Truth, righteousness, the gospel of peace, faith, salvation, and the word of God empower the Christian to do battle against the spiritual forces of evil. To the extent that we neglect these, we become ever more vulnerable. To the extent that we nurture them, we grow in the power of God.

Learning from an ancient master. Athanasius’s Life of St. Antony is a classic Christian text on spiritual warfare. Antony was a monk of the third and fourth centuries who is sometimes credited as the first of the desert fathers and mothers. If he was not actually the first, he was at least quite early. A key theme of the Life is that Antony has withdrawn, but he has not retreated. He is no longer subject to the temptations of life in society, such as sensual pleasures. These simply aren’t available in the desert. Yet he is nonetheless tempted because the desert is the haunt of Satan and his demons, and thus his engagement with the demonic is much more direct than it would have been had he remained in town.

On the reality of the demonic, Antony reiterates the teaching of Ephesians 6:12: “[W]e have terrible and villainous enemies – the evil demons, and our contending is against these, as the Apostle said – not against flesh and blood, but against the principalities, against the powers, against the world rulers of this present darkness, against the spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places. So the mob of them is great in the air around us, and they are not far from us.” Antony’s life of extreme asceticism and total devotion to God allows him to perceive spiritual realities that others cannot.

Antony teaches us that the primary weapons of demons are deception and evil thoughts. “But we need not fear their suggestions,” he says, “for by prayers and fasting and by faith in the Lord they are brought down immediately.” Christian piety is a strong defense against the wiles of the devil. Demons, he says, are nevertheless persistent in their attempts to mislead the faithful. In the face of their ongoing attacks we must remember that Christ has taken from them any true power. “And, like scorpions and snakes, he and his fellow demons have been put in a position to be trampled underfoot by us Christians. The evidence of this is that we now conduct our lives in opposition to him.”

We are able to stand against the demonic because Christ has empowered us to do so. The authority of the Christian is derivative of the authority of Christ. If we stay close to Christ, we continue to walk in his authority. As we drift away, we are ever more susceptible to schemes of our enemy.

In the last several years I have prayed many times that God would strengthen those who are under spiritual attack. Years ago I dropped the ball. I don’t plan to make the same mistake again. The unseen world is real. Angels are real. Demons are real. The power of Christ to stand against the wiles of the devil is real, and it is ours if we but ask.

David F. Watson is Academic Dean and Professor of New Testament at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. His most recent book is Scripture and the Life of God: Why the Bible Matters Today More than Ever. He blogs at www.davidfwatson.me and is one of the hosts of “Plan Truth: A Holy Spirited Podcast.”

by Steve | Mar 17, 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Articles, March/April 2020

By Beth Felker Jones –

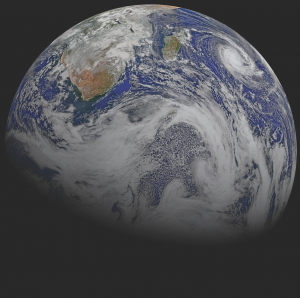

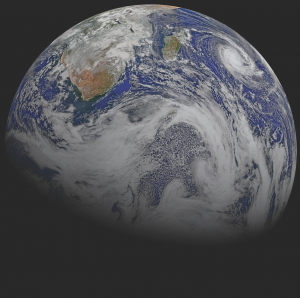

Composite image of southern Africa and the surrounding oceans captured by six orbits of the NASA/NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership spacecraft.

“And he showed me more, a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, on the palm of my hand, round like a ball. I looked at it thoughtfully and wondered, ‘What is this?’ And the answer came, ‘It is all that is made.’ I marveled that it continued to exist and did not suddenly disintegrate; it was so small. And again my mind supplied the answer, ‘It exists, both now and forever, because God loves it.’ In short, everything owes its existence to the love of God.”

These words are from Julian of Norwich, a medieval Christian who recorded a number of revelations of God’s love. The vision above, in which God shows “all that is made” to Julian in the form of “a little thing, the size of a hazelnut,” is one of the most well-known of Julian’s revelations. In light of this vision of creation’s fragility, of its utter dependence on God, Julian marvels that it exists at all, and she draws three truths from it.

The first is that God made it; the second is that God loves it; and the third is that God sustains it.

In these elegant points, Julian sums up the Christian doctrine of creation, and she does so in a way that gets at both head and heart. The doctrine of creation is not first about the obvious trigger points in the contemporary North American conversation, and this means that we may require some retraining in order to practice the doctrine well. When we hear the word creation, we have been primed to expect either a tribute to nature or a scientific account of the origins of the universe.

We think of majestic wilderness and towering pines, or we think of evolution or dinosaurs or carbon dating. Christians may well have something to say about those things, but if we get hung up there, we miss the sweetness at the heart of the doctrine. Philosopher Janet Martin Soskice notes that “the biblical discussions of creation” are “concerned not so much with where the world came from as with who it came from, not so much with what kind of creation it was in the first place as with what kind of creation it was and is now.” The doctrine of creation is about the dependence of all things on God the Creator and, as Julian saw, the love the Creator bears for all that he has made.

This means that the doctrine of creation cannot begin with appreciation for natural beauty. Nor can it begin as a conversation with science. It must begin with the character of the God who is Creator, who made and loves and sustains all that is.

In relationship to creation, Christians tend to notice two things about the Triune God. First, God is not one of the things in this world, and so our doctrine about this world will have to take account of the unfathomable difference between it and God. God is utterly distinct from creation; that distinctiveness is behind the psalmist’s cry, “Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever you had formed the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God” (Ps. 90:2).

Second, the same God who is not of this world is nonetheless intimately involved in it. Indeed, creation depends on God for its ongoing existence at every moment. The doctrine of creation is about God, and so our education about it should begin not with creation itself but with God’s revealing Word. It is not by studying butterflies or stars but “by faith [that] we understand that the worlds were prepared by the word of God” (Heb. 11:3). The Triune God is not some generic god, and our doctrine of creation will have to be about the relationship between creation and this Creator, the Creator who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. “All things came into being through” the Word made flesh, Jesus Christ, “and without him not one thing came into being” (John 1:3).

This is the personal God who lives in personal relationship with creation. The doctrine of creation points us to faithful practice as creatures of a creator God, creatures who live in a world that exists for God’s loving purposes: “For we are what he has made us, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life” (Eph. 2:10). We are created in Christ Jesus, and we are created for Christ Jesus: “For in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers – all things have been created through him and for him” (Col. 1:16). Jesus is both the source and the purpose of creation. We live in a world that has a point, a world that matters. The good news that “all things” are “for him” has enormous implications for the Christian life.

God Made It: Creatio ex nihilo and the Power of God

Julian’s categories show that talk about the doctrine of creation is not limited to the beginning of all things – God’s original creative action in bringing all things into being – but Christian conversation certainly tends to start there. Scripture starts there too, as the familiar first line of Genesis invokes “the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1). The first chapters of Genesis show us a world in which God has made all things. Those first chapters set up a way of thinking about the God who created all that is and about God’s relationship with creation. Old Testament scholar Sandra Richter sums up the theological vision of the creation story, highlighting its distinction from ancient Israel’s neighbors.

“Yahweh was a god unlike the others of the ancient Near East, one who stood outside and above his creation, a god for whom there were no rivals and who had created humanity as his children as opposed to his slaves,” she writes. “Thus I think Genesis 1 was intended as a rehearsal of the creation event (where else would you start the story?) with the all-controlling theological agenda of explaining who God is and what his relationship to creation (and specifically humanity) looked like.”

Not just the first chapter of Genesis but also the whole of Scripture points to this creator God. The testimony of Genesis is that of the end of the Bible as well, of the book of Revelation, which praises God with the words, “You are worthy, our Lord and God, to receive glory and honor and power, for you created all things, and by your will they existed and were created” (Rev. 4:11). God the Creator has no rivals, yet all that is was made to be in loving relationship with the same sovereign God.

In the Christian tradition, the phrase “creation out of nothing” (in Latin, creatio ex nihilo) synthesizes and affirms the biblical testimony pointing to the kind of act with which God first created everything. God created all that is, the summary phrase announces, out of nothing. The phrase invokes the unchallenged majesty of the creator God, without whom nothing exists or ever has existed. The phrase also points, then, to the truth that all that exists, the totality of creation, is God’s work and belongs to God. There are no exceptions. In the words of the Nicene Creed, “all that is, seen and unseen,” is God’s. The implications of the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo can be better understood when we compare the doctrine to the false options that it excludes. If God created out of nothing, then God did not create out of something. Nor, if God created out of nothing, did God create out of his own divine being.

It is easy enough for us to think about acts of creation out of something. The sculptor creates from stone or clay, and the gods of Israel’s ancient Near Eastern neighbors were understood to create out of preexisting chaos or even out of the bodies of their slain enemies. Or, on certain understandings, a god might be understood to create from preexisting matter, from stuff that was already there alongside the god, primordial ooze or a hot, dense core of material that would later explode with a bang. The claim that God created, not out of something, but ex nihilo is a claim that nothing has status alongside God. The repeated testimony of Scripture is that only God is eternal; only God has no beginning; there is none like God.

To deny that God created out of preexisting stuff is to deny that anything, in all creation, has godlike status. In some ways, the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo is simply an implication of monotheism; it is one more way of affirming that “the LORD is our God, the LORD alone” (Deut. 6:4).

And because the doctrine of the Trinity is a deeper understanding of this core Old Testament reality, creatio ex nihilo is an implication of trinitarian theology as well. There is none like the Lord, none alongside him. The doctrine of creation denies that God created out of something – be it chaos or a sea dragon, primordial ooze or a hot, dense core – but it does not deny that God, having already created, then works in and with all sorts of created things. God’s initial act of creation is ex nihilo, but this does not preclude God’s working with and through that which he has created already. Christian thought has no problem with scientific theories about how creation works, but it cannot bear the idolatry of scientism, which would reduce creation to what can be seen and measured. A world that God created from nothing cannot be a world of bare materialism, bereft of divine reality. A world that God created from nothing cannot be the world of deism, in which God holds back, distant and standoffish, from what he has made. A world ex nihilo is, instead, a world full of God’s presence and power.

To deny that God creates out of his own divine being is to recognize the difference between God and creation. This difference is fundamental to Christian thought, and being reminded of it is the ongoing stuff of Christian life. We can imagine acts of creation out of one’s own being. Reproduction works as an analogy. An infant is formed from the stuff of her parents, hydras reproduce new hydras by budding, and both human babies and newly budded hydras are of the same species as their “creators.”

We could envision a god who fashioned creation out of his own being, making a creation that would itself be divine. The whole world as we see it in Scripture, though, which shows us the God who is more than we can conceive and beyond the things of this world, teaches us something else. So, Christian thought consistently rejects all forms of pantheism, the belief that the world is itself divine, and panentheism, the belief that God and the world are so bound together that God could not exist without the world. Christians see, instead, a measureless and qualitative distinction between Creator and creature, between God and all that has been created.

God is God, and we are not. This is another way in which affirmation of God as Creator ex nihilo is a reaffirmation of the biblical proscription against idolatry. Sinful human beings repeatedly confuse creature and Creator, treating the world as divine, exchanging “the truth about God for a lie” and worshiping and serving “the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom. 1:25), but the doctrine of creation trains us in another direction, reminding us that there is no god but God. The doctrine of creation affirms the goodness of what God has made, but it makes no allowance for nature cults and zero room for worshiping human beings and pursuing selfish human ends. The doctrine of creation puts Creator and created in their proper places, insisting that created good things are always dependent, always finite, and always subordinate to the Creator.

God does not need creation in order to be who God is; God is not lacking in love or goodness or relationship in any way that makes creation necessary. Theologian Stephen Long explicates, “God does not create because God is lonely. God does not create because God needs friends. God is not the lone patriarch, the strong silent type who secretly desires to ‘open up’ to us but cannot do so without our help. God does not create because God has to.” In this, we can appreciate a great gift. God creates, not because God needs us, but because God wants us. So, Rowan Williams asks us “to bend our minds around the admittedly tough notion that we exist because of an utterly unconditional generosity: The love that God shows in making the world, like the love he shows towards the world once it is created, has no shadow or shred of self-directed purpose in it; it is entirely and unreservedly given for our sake. It is not a concealed way for God to get something out of it for himself, because that would make nonsense of what we believe is God’s eternal nature.”

Creation is the overflowing of God’s goodness and love outside of God’s own life. Creation is excessive. Creation has all the characteristics of a good gift: it is freely given, without constraint; it is given in love for the other, without selfishness; it is not a grasping, grudging thing, with so many strings attached. Creation is the free work of an all-sufficient God of abundance, the God whose love and mercy is always more than we can imagine. Athanasius (c. 296-373) rejoices: “For God is good – or rather, of all goodness He is Fountainhead, and it is impossible for one who is good to be mean or grudging about anything. Grudging existence to none therefore, He made all things out of nothing through his own Word, our Lord Jesus Christ.” Creation is made for relationship with this gift-giving God, and “its basis,” says theologian Kathryn Tanner, is “in nothing but God’s free love for us. The proper starting point for considering our created nature is therefore grace.”

The doctrine of creation out of nothing is thus the Christian alternative to other possible ways of understanding the origins of all things. Christian faith is not pantheistic, nor does it subscribe to bare materialism or cold deism. Rather, Christians worship the God who is truly other than the world but, far from disdaining that world, inhabits it powerfully and personally. The God who creates ex nihilo is Lord over and lover of creation. The same God who made the light and the darkness, the waters and the sky, is the one who raised Jesus from the dead, who “gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Rom. 4:17).

Beth Felker Jones is associate professor of theology at Wheaton College. This essay is adapted from her book, Practicing Christian Doctrine: An Introduction to Thinking and Living Theologically (Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2014, www.bakerpublishinggroup.com). Used by permission.

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.

I was in elementary school when I first grasped that the death of Jesus was a big deal. On Good Friday, my mom and dad signed me out of class in time for the noon church service. It was somber and stiff and formal – but I was out of school for the rest of the day. It got my attention.