by Steve | Dec 30, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

It is hard to wrap our minds around how things have changed in The United Methodist Church over the past year.

Last January, we were looking forward to a General Conference meeting in August 2022. The Protocol of Grace and Reconciliation through Separation was on track to be adopted and provide an amicable and uniform way for congregations to separate from the denomination in order to join a new Methodist entity (for traditionalists, the Global Methodist Church – GMC). The value of the Protocol was that it allowed annual conferences to separate, negating the need for hundreds of local church votes that could be divisive in a congregation. It allowed United Methodists outside the U.S. to separate with their property. The Protocol allowed local churches to vote to separate by a majority vote, rather than two-thirds, and without making any payments to the annual conference. It allowed the unfunded pension liabilities to be transferred to the new Methodist denomination, so that churches would not have to pay it up front. It created a uniform pathway and rules for separation that did not allow annual conferences to jack up the price or create onerous discernment processes.

The Protocol was our chance as a denomination to do what other mainline denominations had not done – provide an amicable way to separate while blessing each other through the process. It could have given a witness to the world that it is possible for Christians to resolve their differences in a loving and respectful way. It would have allowed the vast majority of United Methodists to fairly and equitably choose the future that best reflected their beliefs, without pressure or coercion.

Unfortunately, it was not to be, and the opportunity was lost. In February, the Commission on the General Conference made the decision to further postpone the General Conference until 2024. Good News believes that behind-the-scenes pressure led to that decision, as bishops and conference leaders began to realize how many annual conferences and local churches would indeed separate when the trust clause and financial obstacles were removed. In a panic, they determined to fight separation and keep as many conferences and churches in the fold as possible, regardless of the preferences of those church members.

In response to this unjustified delay, many traditionalist Methodists had had enough. Members and financial support for local churches were slipping away. In order to preserve the integrity of their faith commitments, many local churches saw a need to act, rather than wait for two more years under a growing progressive tidal wave carrying the denomination away from those traditional faith commitments.

As a result, the leaders of the Global Methodist Church announced their intention to launch the new denomination on May 1. They invited all local churches that desired to separate and align with the new denomination to take steps immediately to do so under provisions already in the Book of Discipline that allow local church disaffiliation.

The defeat of the Protocol became more certain when all the centrist and progressive leaders and organizations that had negotiated and endorsed the Protocol withdrew their support in the spring. They cited “changed circumstances” as their reason for backing off from the commitment they had made in 2020 to pursue the Protocol as a means toward an amicable resolution of the church’s conflict. Sadly, in failing to promote the Protocol and in withdrawing their support, they sealed the change in approach from negotiation to confrontation. Most of the dire consequences the Protocol was meant to avoid have become a reality.

Again unfortunately, the Council of Bishops and some individual bishops decided to fight against separation and create an adversarial relationship with separating churches. They first argued that, without the Protocol, annual conferences should not be able to vote to separate, and they got the Judicial Council to agree, closing that door. Next, they argued that annual conferences should not be allowed to reduce the terms of separation below what Par. 2553 requires, and they got the Judicial Council to agree, closing the door to the use of Par. 2548.2. (This was after a team of bishops had already spent months negotiating with Wesleyan Covenant Association leaders on possible terms for using Par. 2548.2. The abrupt reversal of course by the Council of Bishops was breathtaking.)

Then, a number of bishops led their annual conferences to impose additional financial costs for disaffiliation, on top of the two years’ apportionments and unfunded pension liability payment required by Par. 2553. Initially, there were about a dozen annual conferences making disaffiliation practically impossible due to heavy financial burdens. A couple conferences have backed off their requirements, leaving currently ten conferences in that next-to-impossible category.

An additional dozen conferences have added financial burdens that increase the cost or lengthen the process, but not so much as to make disaffiliation nearly impossible. These conferences are discouraging disaffiliation, but are not preventing it. At the same time, fortunately, over 30 annual conferences are following a straight 2553 process with no added terms, and a few conferences have taken action to reduce the payments by applying annual conference reserves.

Then many bishops outside the U.S. have not allowed congregations to disaffiliate with property because they say Par. 2553 does not apply outside the U.S. This is happening even though the actual language of 2553 says, “This new paragraph became effective at the close of the 2019 General Conference.” With the lack of accountability for bishops, there is no effective way to force bishops to abide by the Discipline in this matter. And the Council of Bishops appears to support this wrong interpretation.

Some European districts and annual conferences took matters into their own hands, regardless of what the Discipline says. Bulgaria was the first conference to vote to separate from the UM Church and became the first annual conference in the GMC. Other Europeans are in the process of following suit. GMC churches are being planted in the Philippines, and some districts or annual conferences there may still try to separate. The GMC is forming in some parts of Africa, while other parts of Africa are working toward the eventual goal of separating as annual conferences. (U.S. law does not apply in other countries, and the laws in those countries sometimes enable changing the trust clause.)

The Council of Bishops determined that only Par. 2553 should be used for disaffiliating churches. That paragraph expires on December 31, 2023. Comments by episcopal leaders indicate a desire to turn the page and move on from conflicts over separation, so it is unlikely most bishops will support an extension of Par. 2553 or a similar disaffiliation process past the deadline. We know of two conferences that have promised to do so.

The summer and fall saw about 17 U.S. annual conferences hold special sessions to approve the disaffiliation of local churches. At this point, over 2,000 U.S. congregations have been approved to disaffiliate and will be separated by January 1. Hundreds more are in the process to disaffiliate at regular annual conference sessions next spring. By the end of next year, we could see a total of 3,000 to 5,000 U.S. churches having disaffiliated. Congregations continue to work through the particular requirements and processes of their annual conference, as each annual conference is different.

At the same time, in some conferences where the terms of disaffiliation are egregious, churches have resorted to legal strategies, including filing of lawsuits against the annual conference. This is the very litigation that negotiators of the Protocol hoped to avoid. This unfortunate situation was entirely preventable.

This fall brought new clarity about what to expect in the post-separation United Methodist Church. The five jurisdictions in the U.S. met to elect bishops. Not one traditionalist was elected. All five jurisdictions passed overwhelmingly three resolutions affirming LGBTQ+ persons, same-sex marriage, and the ordination of non-celibate gays and lesbians as clergy, as well as urging a moratorium on all complaints and charges related to such. The momentum is toward removing from the Discipline the traditional language regarding the definition of marriage and sexual ethics.

That momentum received a boost in December from the decision by the Judicial Council to disregard the Discipline’s requirement that delegates to General Conference be elected no more than two years prior. The delegates to the 2024 session of General Conference will be (for the most part) those elected in 2019, which saw a marked swing toward a more progressive delegation. The decision also deprives Africa of the estimated additional 44 delegates to which they would otherwise be entitled, reducing the traditionalist vote by over five percentage points.

It seems clear that the 2024 General Conference will have a progressive-centrist majority, in contrast to previous General Conferences that have had a narrow traditionalist majority. The makeup of General Conference encourages one to believe that the language in the Discipline and church policy will take a progressive turn. It also calls into question whether General Conference will pass a new disaffiliation process to replace the expired Par. 2553. Such an effort will require the support of some progressives or centrists, who will have little incentive to do so beyond an inclination to do what is right and loving under the Golden Rule. One hopes that will be enough, but there are no guarantees.

So, a year that started off with great promise for a clear and amicable resolution of the church’s conflict through a plan of separation ends with the parties engaged in conflict and litigation, penalizing churches that want to disaffiliate and creating animosity between the parties that bodes ill for any future cooperation.

Despite the changed situation, individual congregations and clergy are choosing (and in some cases fighting) to disaffiliate from a denomination that is making a swift shift toward a more theologically progressive church. Once the most theologically conservative mainline denomination, the UM Church is fast joining its mainline sisters in pursuing a progressive ideological agenda.

Working through adversity will help solidify congregations’ theological commitments and the decision to align with a new Methodist denomination. It will eventually make the Global Methodist Church stronger. Even as congregations disaffiliate, many are experiencing new growth and vitality, as well as the miraculous provision of God for their leadership and finances. The more difficult the situation, the more clearly we can see the hand of God at work, doing what only he could do when we are beyond our own abilities and resources.

2022 has been a momentous year, filled with bewildering twists and turns in the development of the Methodist story. It has also been a momentous year, filled with evidence of the Lord’s leading and empowerment. As we end this year, we can be encouraged by the last words of our founder, John Wesley, “The best of all, God is with us.” May you experience the presence of Immanuel – God with us – now and in the year ahead.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Dec 9, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

By the end of this year (2022), about 2,000 local churches will have disaffiliated from The United Methodist Church. Hundreds more will do so next year. Where will they end up? A few will remain as independent Methodist churches. The vast majority will align with another Methodist denomination. But which one?

The leading candidate for most congregations is the Global Methodist Church (GMC). As one who helped in a small way to form that denomination, it is my recommended option to local churches. It was founded by United Methodist renewal leaders who have been in the struggle for years and in some cases decades. The GMC was formed in such a way as to address some of the shortcomings we have experienced in the current United Methodist crisis. I believe it is well positioned to give good leadership and resourcing to local congregations for ministry in the 21st century.

There are other options, however. Two prominent churches have aligned with the Free Methodist Church. Within the Wesleyan sphere, other options include the Church of the Nazarene, the Wesleyan Church, and the Congregational Methodist Church.

The purpose of this article is to compare a few important variables in each of the denominations, so that congregations have a realistic idea of what each has to offer. One should explore more deeply those denominations that are of interest, since some positive factors might be offset by other negative factors, and vice versa. But the variables I have chosen to highlight might be non-negotiables, or at least very important, in deciding whether to explore a particular denomination further.

Doctrine

Since the root of the divide in United Methodism is doctrinal, it is important to look at the doctrines of any potential denominational homes. All the denominations mentioned above, including the UM Church and the GMC, espouse Wesleyan doctrine on paper, including a clear traditional definition of marriage and human sexuality. What has caused division in the UM Church is the failure to ensure that clergy and bishops maintain their preaching and teaching within the boundaries of our doctrinal standards.

The GMC promises a more robust doctrinal accountability. In addition, the GMC has added the Apostles and Nicene Creeds to its doctrine, emphasizing the continuity that the GMC has with historic, traditional Christian doctrine.

With a lack of anecdotal evidence at this point, it is difficult to discern how faithful the other Methodist denominations are to their doctrinal statements. My assumption is that they take doctrinal accountability more seriously and their preaching and teaching stays within the boundaries of their doctrines.

Trust Clause

As United Methodists are experiencing, the presence of a trust clause means that the denomination has first claim on the local church’s property and requires denominational approval for disaffiliation, as well as for the sale, purchase, renovation, or mortgage of local church property. The current waves of disaffiliation would not be the wrenching battle that it is without the trust clause and the denomination’s ability to make the process difficult or even impossible in some places.

The GMC has no trust clause. The congregation has complete control of its property in every way. In addition, there is a simple and straightforward process for local churches to disaffiliate from the GMC, should that ever become necessary.

The Free Methodist Church is allowing churches who transfer into the denomination to maintain control of the property they bring with them. Any new property acquired by the congregation while in the Free Methodist Church is subject to a trust clause.

The Wesleyan and Nazarene Churches both have a trust clause giving the denomination control of local property. The Congregational Methodist Church does not have a trust clause.

Bishops

United Methodist bishops are elected for life, except in a few of the central conferences outside the U.S. Retired bishops continue serving on the Council of Bishops, with voice but without vote. As such, retired bishops continue to have a strong impact on the decisions and directions of the Council.

The GMC will have bishops elected for a term to be determined at the convening General Conference. It will probably be a term limit of 12 years served as an active bishop. Retired bishops will not have a continuing official role in guiding the denomination.

Free Methodist bishops are elected to four-year terms and eligible for reelection. Nazarene leaders are called General Superintendents and six are elected to four-year terms and eligible for reelection. The Wesleyan Church has one General Superintendent for the entire denomination, elected to a four-year term and eligible for reelection. The Congregational Methodist Church has one president with minimal authority, since it is a very small denomination and operates with a congregational polity.

Clergy Appointment

In The United Methodist Church, clergy are appointed by the bishop with the involvement of the district superintendent and some level of input from the congregation that can vary from one conference to another. In the GMC, appointment will also be by the bishop with the involvement of the district superintendent, but with a much greater and more consistent level of input from the congregation. It is further proposed to the GMC convening General Conference that churches be allowed to seek out their own pastor if they desire, with the assistance and final approval of the bishop. Whereas United Methodist clergy appointments are usually made on a year-by-year basis, GMC appointments will be made as intentionally longer-term appointments, affording the local church more pastoral consistency.

The Free Methodists Church are appointed by a Ministerial Appointments committee chaired by the bishop. That committee includes both laity and clergy from the annual conference. Pastors serve until a change is requested by the local church or by the pastor, or until a missional need elsewhere calls for a change.

Both the Wesleyan and Nazarene Churches have a congregational call system for clergy. They extend the call for an indefinite term, with review at least every four years. The Congregational Methodist Church also has a call system, with pastors being called to an open-ended term of service.

Denominational Financial Support

United Methodist congregations generally pay between 7-15 percent of their budget to the annual conference, jurisdiction, and general church. While many churches do pay 100 percent of their apportionments, the average collection rate for apportionments runs between 75 and 90 percent for the annual conference as a whole.

The GMC is initially asking churches to give one percent of their operating income to the annual conference and one percent to the general church. There is a cap of no more than five percent to the annual conference and 1.5 percent to the general church. Mission giving will not be through connectional giving, but through direct giving to partner annual conferences, districts, projects, and congregations in other areas.

Apportionments for Free Methodists amount to between 10 and 13 percent of local church income. For the Wesleyan Church, it is 11 percent. The Nazarene Church expects 15 percent, which also includes the pastor’s pension. The Congregational Methodist Church congregations give whatever they decide to give beyond the local church, and there is minimal denominational structure.

Denominational Size

One important factor is the size of the denomination and whether there will be enough churches and clergy to allow for supportive fellowship, cooperative work, and adequate resourcing of the local church. Another consideration is whether an influx of United Methodist members and congregations would overwhelm a denomination’s current culture.

Of course, no Methodist denomination rivals the size of United Methodism, which currently has about 6.2 million members in the U.S., along with approximately 30,000 congregations (2020). There are also over 5 million members outside the U.S. in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

It is estimated that 3,000 to 5,000 congregations will disaffiliate from the UM Church by the end of 2023. We have not yet compiled the membership numbers of disaffiliating churches, but a conservative estimate is that those disaffiliating churches represent 300,000 to 500,000 members. If perhaps 80 percent join the GMC, that would yield a denomination of 240,000 to 400,000 members by the end of 2023.

The largest of the other Wesleyan-oriented denominations is the Nazarene Church, with 637,000 members in 5,280 congregations in the U.S. (2016). Globally, the Nazarenes have 2.67 million members in 30,600 congregations. It is a truly global denomination, with congregations in Central and South America, Africa, Eurasia, and Asia/Pacific. Looking at just the U.S. part of the church, however, if substantial numbers of United Methodists joined the Nazarenes, they could make up a significant percentage of the members.

That situation is even more pronounced for the other Methodist-oriented denominations. The Wesleyans have about 125,000 members and 234,000 total attendees in 1,500 congregations in the U.S. (2019). The Free Methodists have 77,000 members in 1,050 congregations (2015). The Congregational Methodist Church has about 15,000 members in 150 congregations.

Size considerations and unique denominational distinctions were important factors in the need to start the Global Methodist Church. If all the disaffiliating United Methodists decided to join one of the existing Methodist denominations, it would be very difficult. 400,000 United Methodists joining the Nazarenes would create a church of 1.037 million in the U.S., of which 39 percent would be former United Methodists. If they joined the Wesleyan Church, there would be 634,000 members, of which 63 percent would be former United Methodists. We would dwarf the Free Methodists or Congregational Methodists.

It is unlikely any of those denominations would welcome that many new members from another denomination. The impact would be devastating on the culture of the receiving denomination. It would be like having a congregation of 100 members experience 65 or more new members joining it all at once. Those new members would want to have a significant voice in how the church is organized and run, which could cause resentment by the existing members and would unquestionably change the character of the congregation. Avoiding this awkwardness was one of the primary drivers in the need to start the GMC.

History

Another factor in this alignment decision is that each of the existing Methodist denominations has its own history and tradition. Many of us are used to United Methodist history and tradition, dating back to John and Charles Wesley (1740’s) and Francis Asbury, William Otterbein, and Jacob Albright (1790’s). The Wesleyan Church (1843), Congregational Methodist Church (1852), Free Methodist (1860), and Nazarene (1908) all have their own set of “founding fathers and mothers” and their own history and tradition. They do share Methodist history from the Wesleys until the time of their own founding, often as a separation from the Methodist Church. Joining one of these other denominations would be to adopt that history and tradition as one’s own.

When two people get married, they each bring their own family history and tradition with them on a relatively equal basis. Together, they start something new and create some elements of new history and new tradition to build on what they received. They both learn each other’s family history and tradition and respect that history and tradition.

Joining an existing Methodist denomination, however, would be like getting married and leaving one’s own history and tradition behind, while learning and adopting a new history and tradition that is well over a century old. That other Methodist denomination would not feel inclined to “catch up” on our United Methodist history and tradition, so we would not be on an equal basis. We would be adopted into a new family and learn a new way of doing things that has been established through a long evolution.

By contrast, joining the Global Methodist Church offers the opportunity to be in a denomination where we all have the shared history of United Methodism and the shared experience of going through disaffiliation together. Building on that shared history and experience, we would all be on an equal basis in forming new traditions and new ways of doing ministry together, rather than adopting something that is already set up.

There are pros and cons to both approaches. Some people like having all the questions settled and long established, so would be attracted to joining an existing denomination that has a set pattern of life and ministry. Other people want to have a voice in deciding how things will be done going forward, so would be attracted to a new denomination where their voice could make a difference.

All these factors and many more play into the decision of what denomination to align with. As I have written before, it is much healthier to be part of a denomination, rather than being simply an independent congregation. Hopefully, the above (admittedly biased) reflections and information can be helpful in making that decision.

For further information and research, see the following websites:

Global Methodist Church – globalmethodist.org

Free Methodist Church – fmcusa.org

Wesleyan Church – Wesleyan.org

Church of the Nazarene – Nazarene.org

Congregational Methodist Church – cm-church.org

A chart form of the above comparisons is available HERE.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Dec 8, 2022 | In the News

By Charles L. Harrell

The Baltimore-Washington Annual Conference (BWC) is one of those conferences that Good News and the Wesleyan Covenant Association has identified as imposing egregious terms on disaffiliating local churches, particularly the levy of 50 percent of the church’s property value. The Rev. Charles Harrell reports on a conversation held by the BWC Wesleyan Covenant Association board with Bishop Latrelle Easterling and the conference Trustees appealing for a change in that requirement, critiquing the rationales the trustees provided for levying such a financial burden on local churches. His responses will be helpful in advancing the argument in other annual conferences imposing similar requirements.

Brand Value?

The Trustees presented several reasons why they felt their ask of 50 percent of property value to be justified. One reason was that churches seeking to disaffiliate have had the use of the United Methodist name and all that goes with it, such as the cross-and-flame logo. The argument holds that people looking for a church home see the UM name and symbol, and it attracts them.

Sadly, this claim isn’t as true as it used to be. The Methodist name and related symbols might have been a draw in 1950, perhaps even at the time of the merger that formed the current UM Church in 1968. But the reality is much different now, when denominational identification is often more a liability than an asset. If the Trustees wish to appeal to an argument about the power of denominational identification, that’s fair. But to be credible, it would be better to deploy one that’s not a half-century out of date.

Provider of Pastors?

The Trustees also point out that the conference provides pastors to the churches. This is true. But if the trend lines for membership and worship attendance are any indication of the effectiveness of many clergy, one might expect a little more modesty concerning just who it was who credentialed and sent them. It’s also worth noting that the Trustees’ point could be turned around: it is the local churches that provide a place of employment with salary and other support for those pastors that the conference or districts credential and employ. Oddly, that detail does not seem to figure in the conversation.

Historical Example: Wesley’s Methodism?

The Trustees also pointed out to the WCA leadership that when the Methodist movement started in Britain, later separating from the Anglicans, it didn’t look to claim property but went out on its own. Frankly, this is hilarious: people should blush to say things like this. The Wesleyan societies were organized as what today would be called parachurch bodies. They were never congregations of the Church of England. In a country with a state church like Britain, all church property was under the direct control of the diocese or the occasional patron. Methodism in Britain was not an established free (independent) church at the time of its separation from Anglicanism; and the Church of England was not organized, built, funded or maintained by free congregations, as is the case for American Methodism in all its forms. To compare the Anglican situation in the eighteenth century with the American context today goes even beyond comparing of apples to oranges. Think perhaps apples to footballs.

The Trust Clause

Naturally, the Trust Clause came up in the conversation. The bishop observed that the existence of the Trust Clause should be no surprise, especially to clergy, as it has been there since 1968.

Well, then. That’s a slam dunk, right? Hardly.

In one sense, the bishop was more correct than the history she acknowledged: the Trust Clause goes way back before 1968 to the beginning of denominational Methodism in America. All that history is also on the table, and its origin was not in 1968, but in 1784. In fact, the timeline stretches back further still: the roots of our Trust Clause are to be found in the Model Deed from Great Britain.

The Model Deed was John Wesley’s safeguard to protect the movement’s investments in property after the painful experience of the Fetter Lane Society, where asset control (and the related quality control over the preaching and teaching) was lost. Beginning with the Foundry in London, Wesley made sure his previous mistake wasn’t repeated. Still, only the immediate purpose of the Model Deed and Trust Clause was to maintain control of the property. It was actually designed to pursue a much deeper purpose, which was to place boundaries around the integrity of Methodism’s teaching and practice. In other words, it was created to ensure that property would be used for the exclusive, faithful use of congregations loyal to the doctrine and discipline of the church.

Fast-forward to the present. The landscape is blanketed with property that was provided for at great expense and with much trouble and sacrifice by Methodists across the intervening generations who were faithful to that doctrine and discipline. Only now, the Trust Clause is being used to bully into submission those congregations who want to retain the doctrine that it was instituted to protect. These churches resist their annual conference’s pursuit of policies that are the at odds with the Discipline, to say nothing of Scripture, on points of moral teaching. The Trust Clause has been converted from a safeguard into a bludgeon to compel compliance with conference actions that have defied the order and discipline of The United Methodist Church. It is being used to punish them severely if, based on those same doctrines faithfully held, such churches decide to leave what they discern to be a connection whose fidelity to its roots has been seriously compromised.

Who could have anticipated such a situation? Who indeed might have foreseen that the very property clause designed to maintain integrity would be used against the faithful who hold to the church’s order and discipline, and in fact are so loyal to them that they are willing to sever ties with the denomination rather than abandon them? The apple has fallen far from the tree of 1784, that the Trust Clause could be made to work this way.

It’s Only Money and Property

The Trustees have further suggested that, if the traditionalist concern is really a matter of conscience, as opposed to being about property and finances, then people are free to go their own way at any time. At day’s end, no one is locked into a church building or chained to a pulpit.

Aside from being harsh and cynical, this contention of the Trustees is also more than a little superficial. A proper and faithful theology of wealth can never say, with a toss of the head, “Oh, it’s just money. It’s just property,” as though it were really nothing. (Not incidentally, if that were true, could the Trustees not say it themselves just as easily, rather than pressing for every last nickel?)

But let’s set even that aside. The assets in question are, in many cases, the endowment of generations of faithful Christians. These resources were donated, raised, or provided with great effort and with real costs to persons and families. They came into being by the loving sweat of young and old alike across decades, even centuries in some instances. The use to which they would be put if surrendered, and the ideologies behind that use, are frequently at odds with the hearts that gave it. They can reflect purposes and goals that are diametrically opposed to, even contemptuous of, the vision of the givers of those gifts to the glory of God.

Seeking to retain it for faithful use by the continuing body of worshipers in that place, whatever label they bear, is not a function of greed or a matter of convenience for the departing congregation. It is a recognition that just to surrender these resources, or even a substantial portion, would be ethically problematic.

The 50-50 Divorce Analogy

Sometimes, the division of the UMC is compared to a divorce. There are, after all, divisions of property in a divorce. In such a situation, the aim of any court or judge is to be equitable to both parties. So why isn’t 50 percent a fair figure?

Consider a hypothetical scenario. A couple marries. He has a respected name and worthy reputation. She is thrilled to be joined to his future, and they start a life together with high hopes. So in love is she that she doesn’t mind that, while he has the name, she is bringing all the funds – every cent – that will build their home, and manage their household.

But then, by degrees, things begin to go sour in their life together. While she hangs on patiently and hopefully, he begins unilaterally to change the terms of their union, to the point of betraying his promises to her. Of course, he claims that his understanding has evolved and that he should not be held to such outmoded notions of fidelity. He begins to criticize her and her view of their life together: he suggests that she is slow-witted and hopelessly old-fashioned. He intimates that she will never amount to anything; that everything she’s ever done or achieved is either due to her circumstances or because she wears his name.

So, what does she do? She waits; she pleads; she prays. She reminds him of their covenant together. But he has “moved on,” he says; and he does what he wants because he can. And when she objects, when she pleads the nature of the sacred bond between them, he tells her she can leave any time she wishes. Of course, she’ll need to leave everything behind. His name, of course; but more than that, everything she brought to the union over the years. And even though it was her resources that provided the family home, she has to leave that, too – though there is one “generous” provision: if she wants to keep the dwelling she has paid for, and the contents thereof, she must pay him an additional half of the value she has already given and follow the exact process for doing so that he sets out for her. Else, he keeps it all.

This situation is as heartbreaking as it is unjust, a travesty of the bonds of love and faithfulness that are supposed to undergird a marriage. Any reasonable person would howl with outrage over such an abusive situation in marriage.

Yet this is very much the situation in which our traditionalist churches find themselves. After much patience and prayer amid a deteriorating situation over years, they have determined that their best and most faithful course is to leave a relationship with The United Methodist Church that has become toxic and abusive for them.

The congregations built and purchased the houses of worship to begin with and have maintained them across time. Year by year, these congregations financed the continuing ministry and supported, through their apportionments or “mission shares,” the work of the annual conference and the general Church. They also supported the clergy sent to them.

But the terms of that relationship have been unilaterally changed by the conference, which was to have been to them a benevolent partner in their work. A new pattern has emerged. The conference takes actions which are unfaithful to the covenant, doing so knowingly, willingly, and because it can. When the congregants of these churches object, they are given to understand that they just need to grow a bit, to evolve, and not be so backward or slow-witted. They may be told that anything they’ve been able to do is because of the circumstances of their location or because they have carried the name: the UMC label. If they really want to leave, of course, they can do so; but they take nothing with them for their re-establishment or support: not the name, not the goods – unless, of course, they follow a process that has been dictated to them and pony up another 50 percent of the value they have already raised in real property over the church’s lifetime.

Sadly, what would be unjust if it were about an actual married couple becomes perfectly acceptable when those on the receiving end are a congregation of Christians, fellow brothers and sisters in Christ, who take a different view which they want to hold in peace. Their view is actually in keeping with the doctrine of The United Methodist Church, in alignment with its Discipline, and faithfully reflects the evangelistic and social-Christian mission of that denomination stretching back to its beginning. Demanding the church pay half the property value in order to keep it, when they have already contributed the whole amount, is fundamentally unjust.

Breach of Covenant

The Trustees also took issue with a BW-WCA board member’s having raised a question about breach of covenant as shown by the ordination of persons who are not eligible under the Discipline. This aroused some annoyance, it seems, even though the WCA members were clear that the Trustees were not being blamed for that occurrence, which fell under the responsibility of the Board of Ordained Ministry. “We are all one conference,” came the reply. The WCA member was trying to give the Trustees an “out,” but they clearly didn’t want it.

In that case, then, the situation is even clearer, and the remedy suggests itself readily. Since the church’s doctrine is being upheld by the traditionalists, if anyone should pay a usage fee for the display of the name and logo, it should be those who are teaching and acting at variance with the Book of Discipline. Any fees should be covered in full by the conference which is now usurping the use of the name and logo for a different agenda.

A Moral Issue

A WCA member also questioned the morality of the 50 percent charge. The Trustees didn’t like that and indicated that some offense was taken over the question. The bishop also indicated that it was inappropriate to speak of morality and hoped that would not come up again.

It is totally understandable that the conference leadership would desire to avoid speaking of morality because it is on the wrong side of this question. This is seen from its flagrant violations of the Discipline, from the deceptive misappropriation of Methodist history, and from the fleecing of congregations for resources that the conference had little, if any, real role in building and yet has been benefiting from since the day that those local churches were first chartered. It is on the wrong side in the dismissive contempt it has shown to faithful United Methodists who choose to uphold the teaching represented by the Book of Discipline, and in the leadership’s insinuation of sub-Christian motives on the part of those who dare to take the traditionalist view.

The conference’s leadership is on the wrong side in a larger sense, too: not only concerning matters of human sexuality, but also respecting the universal church’s broader and deeper cherishing of the authority of sacred Scripture back to the witness of the apostles, and its rooting in the divinely revealed religion of Israel.

So, yes, it’s completely understandable that the leadership should find discussions of morality embarrassing, troubling, and burdensome, and express a powerful desire to avoid them at all costs – understandable, but unsupportable.

Grace and Peace

The conference can, and should, yet stand to the full height of its capacity for mercy and peace, availing itself of the wisdom that would come with a more gracious strategy for allowing churches to exit. Such a plan would rely less on the politics of power and more on the recognition that there are no real winners along a road that can only lead to deepened divisions and a more profound bitterness, as we have seen in other denominational splits in recent years.

My prayer and plea is that the BWC through its committees and officers will do the right thing and abolish the 50 percent penalty, even refunding it to those separated churches that have already paid such a crippling price.

Perhaps in all the controversy, the ability to love has been lost in the hearts of many, toward those who see the issues before the denomination in ways different from themselves. But we are all supposed to be grounded in that greater Love, a love which, even amid sharp disagreement, can find a way to be generous of heart and bless the other as we go in different directions, each convinced that we are following God’s call. That’s how we can even now prove to be true brothers and sisters to one another across the debates and divides, and bless those who find that their local church’s future draws them in a new direction, toward a new expression of Methodism.

It’s the higher road for all concerned. Let’s take it.

Charles L. Harrell is an ordained elder in the Baltimore-Washington Annual Conference.

by Steve | Nov 22, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht

With the recent election of thirteen new bishops, the active Council of Bishops will be made up of one-third new members on January 1, 2023. As such, they will play a powerful role in setting the direction of The United Methodist Church into the future. What do their election and the other actions of the jurisdictional conferences tell us about what that direction might be? This article is the second of two surveying that question. The first may be read here.

Traditionalists in the Post-Separation UM Church

Some traditionalists will unquestionably remain in the UM Church following the current spate of separations. A 2019 survey found that 44 percent of United Methodist grassroots members identified as theologically conservative or traditional. Twenty-eight percent identified as theologically centrist or moderate. Twenty percent identified as theologically liberal or progressive. Even if half of the traditionalist members leave the UM Church, those remaining would be more than one-fourth of the church’s members. Their share would still be larger than those identifying as progressive.

The question is whether traditionalists will be represented in leadership of the denomination after separation. In 2016, seven of the 15 bishops elected in the U.S. (nearly half) could be considered theologically traditionalist. (Some of those might be classified more as institutionalists than by their theological perspective, but they at least come from a traditionalist viewpoint.) By contrast, none of the 13 bishops elected now in 2022 could be considered theologically traditionalist.

Due to bishops’ retirements, seven of the 39 U.S. bishops going forward could be considered traditionalist, and even some of them would again be more institutional than traditional in their approach to leadership. At best, that means around 18 percent of the active bishops are traditionalists. If current trends continue and no new traditionalist bishops are elected, that percentage will shrink further, and traditionalists will be grossly underrepresented on the Council of Bishops.

Even more stark is the realization that nearly all the general secretaries of the general boards and agencies of the UM Church reflect a centrist or progressive theology. Traditionalists are underrepresented on the agency staffs and among the agency board members and have been for decades. The same is true in many annual conferences when it comes to district superintendents and conference agency heads and staff.

For the foreseeable future, the traditionalist voice in the UM Church will be a minority voice and not well represented among the denominational leadership. Traditionalist members are not likely to hear their perspective communicated from bishops or general church or annual conference leaders.

Voting Strength

When the jurisdictional delegates were elected in the aftermath of the 2019 General Conference, there was a notable swing toward more progressive delegates being elected, particularly among the clergy. Since then, some of the traditionalist delegates have resigned due to their disaffiliation from the UM Church, further reducing traditionalist voting strength.

The projections made in 2019 were born out by the vote counts at the various jurisdictions. The three progressive resolutions (see page 25 of the link) passed by every jurisdiction obtained over 80 percent support in most cases. The most conservative jurisdiction is the Southeastern Jurisdiction. There, centrists and progressives made up two-thirds of the delegates.

Based on these vote counts, it is likely that the U.S. delegates to the 2024 General Conference will be at least 80 percent centrists and progressives. This would give centrists and progressives a solid majority of the conference if this year’s delegates continue to serve during the General Conference.

If new delegates are elected for the 2024 General Conference, there will be a reduction in U.S. delegates and an increase in African delegates due to changing membership numbers. Unless traditionalists are completely shut out in the U.S., this shift will result in a much narrower margin for centrists and progressives. The wild card here is what would happen in annual conferences that experience high rates of disaffiliation. If those conferences, like Texas, South Georgia, and Alabama-West Florida, shift markedly toward centrist and progressive delegates, that would increase the margin and give centrists and progressives a solid majority at General Conference.

Future Directions of the UM Church

It is abundantly clear from the three resolutions passed by the five jurisdictions that the affirmation of LGBTQ+ persons and lifestyles will be a primary agenda item for the denomination. The Queer Delegates’ Resolution (the official title) affirms that each jurisdiction:

Commits to a future of The United Methodist Church where LGBTQIA+ people will be protected, affirmed, and empowered in the life and ministry of the church in our Jurisdiction, including as laity, ordained clergy, in the episcopacy, and on boards and agencies.

One jurisdiction held a two-hour presentation for all delegates on combatting heterosexism, which affirmed all sexual orientations and gender identities and promoted the acceptance of same-gender relationships and transgender reassignment.

Another priority for the UM Church going forward will be to continue addressing the challenge of racism. Two of the jurisdictions encountered difficult circumstances around bishop elections and nomination of candidates that contributed to a perception that racism had entered into the process. One jurisdiction adjourned into executive closed session to address issues of racism connected to the conference.

The United Methodist Church is the second most white mainline Protestant denomination in the U.S. (94 percent white), following the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. Unfortunately, even a decades-long focus on representation and gender and ethnic diversity in the church’s leadership has not translated into a growing diversity at the grass roots of the church. Nevertheless, the emphasis on diversity continues. This strategy deserves rethinking.

A third priority for the UM Church will be instituting a regionalized system of governance. The Christmas Covenant proposal was overwhelmingly endorsed by all five jurisdictions. This proposal would create the U.S. part of the church as its own regional conference, along with three conferences in Africa, three in Europe, and one in the Philippines. Each regional conference would have broad powers to create its own rules and standards and adapt the Book of Discipline to fit the context and opinions of that region. The driving force behind this proposal is to allow the U.S. and Western European parts of the church to affirm LGBTQ+ relationships and lifestyles, while allowing Africa and perhaps the Philippines to maintain their more traditional understandings of marriage and sexuality. (I have written a critique of this proposal.) Although there may be a majority of delegates supporting this proposal, it will not have the two-thirds vote needed to pass General Conference unless the African delegates can be persuaded to support it. African leaders have previously said they could not remain in a church that endorsed same-sex relationships, even if they themselves were not forced to join in that endorsement. African delegates and members have the numbers single-handedly to block regionalization if they do not support it.

A fourth priority for the UM Church going forward will be a realignment of conference boundaries. Due to the disaffiliation of 10-20 percent of United Methodist members and churches, some annual conferences will become too small to be sustainable. There will likely be mergers and consolidation of some annual conferences. The jurisdictions recognized this reality by not filling all the vacant bishop positions. There will be seven episcopal areas with no resident bishop, with those areas being covered by nearby bishops (three in Northeast and two each in Southeast and South Central; additional vacancies will occur in North Central in 2024 due to episcopal retirements). Some annual conferences may remain intact but share a bishop with an adjacent annual conference.

There is also a working group studying the possibility of revising or eliminating the jurisdictional system altogether, which came up during floor debate in some of the jurisdictional conferences. The jurisdictions are a holdover from a racist past, having been formed in the 1939 Methodist Church merger of North and South, which also created a separate jurisdiction for Black Methodist congregations and clergy. That separate jurisdiction was eliminated in the 1968 United Methodist merger, but the regional jurisdictions remain and have fostered regional differences in the church that led to disunity. Changes to the jurisdictional system will require a two-thirds vote to amend the church’s Constitution.

Given these four priorities, two of which would entail major structural changes, it is questionable whether denominational leaders will have the bandwidth or energy to pursue essential components like evangelism, church revitalization, caring for the poor, church planting, and cross-cultural ministry. Local churches will be expected to assume primary responsibility for these areas, and they may or may not be equipped to do so.

The 2022 jurisdictional conferences provided an illuminating look at the current reality of the UM Church in the U.S., as well as some of the potential directions the denomination might take into the future. In the words of Jesus, “Anyone with ears to hear should listen and understand!” (Matthew 11:15).

This article was originally published by Firebrand and is reprinted with permission. The full article may be read at: Firebrandmag.com.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and is the vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Nov 18, 2022 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht —

With the recent election of thirteen new bishops, the active Council of Bishops will be made up of one-third new members on January 1, 2023. As such, they will play a powerful role in setting the direction of The United Methodist Church into the future. What do their election and the other actions of the jurisdictional conferences tell us about what that direction might be? This article is the first of two surveying that question.

More Diversity

According to news reports, this group of elected bishops represents several “firsts,” recognizing the expanding ethnic diversity of the Council of Bishops. David Wilson is the first Native American bishop in the UM Church. Carlo A. Rapanut is the first Filipino American bishop. Hector A. Burgos-Nuñez is the first Hispanic/Latino bishop in the Northeastern Jurisdiction. Delores “Dee” Williamston is the first Black woman bishop in the South Central Jurisdiction. Cedrick D. Bridgeforth is the first openly gay Black male bishop. (Karen Oliveto was the first openly gay female bishop, elected in 2016.)

The diversity, however, did not extend to electing one single theological traditionalist or conservative bishop.

Expanding the “Big Tent” Leftward

The theological diversity of the newly elected bishops seems to run only in a more progressive direction. For example, all 13 bishops favor changing the language of the Book of Discipline’s definition of marriage as the union of one man and one woman. They would endorse the ordination of practicing gay and lesbian pastors and support the ability of pastors to perform same-sex weddings.

In other words, the entire slate of new bishops made it clear that they reject the United Methodist consensus on marriage and sexuality for the past 40 years of Christian “conferencing” at General Conference – including the 2019 gathering in St. Louis that was supposed to resolve our dispute.

However, the most eye-opening theological expansion was the statement by Kennetha Bigham-Tsai, from the North Central Jurisdiction, who was the first of the 13 elected. In a mystifying answer to a question during her candidacy interviews, she stated, “It is not important that we agree on who Christ is. … God became flesh, but not particular flesh. There’s no particularity around that. God became incarnate in a culture, but not one culture. There is mystery and wideness and openness and diversity in who Christ is and who God is, so that every living human being has a way to touch God, to connect with God, to have a relationship with God in Christ.”

This picture brings to mind the parable of the blind men and the elephant, which originated in India centuries before Christ. In the parable, seven blind men who have never seen an elephant touch different parts of the elephant’s body (leg, tail, side, tusk) and come away with very different understandings of what an elephant is like. It seems like Bigham-Tsai is saying that Jesus Christ is different things to different people, so that each person has a way of connecting with Jesus.

It is true that Jesus meets each of us where we are in a way that opens our ability to receive him as our Savior and Lord. That is the essence of prevenient grace. However, the radical pessimism about our ability to have a unified understanding of Jesus’ basic identity is unwarranted and contrary to an orthodox understanding of Christianity.

When Jesus asked his disciples, “Who do you say I am?” Peter responded, “You are the Christ (Messiah), the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:15-16). Jesus blessed Peter for his understanding that had been revealed to him by the Father, thus affirming Peter’s statement. We ought to be able at least to have a common understanding that Jesus is the Messiah, God’s Son.

Our United Methodist doctrinal standards go into much greater detail about who Jesus is.

The Son, who is the Word of the Father, the very and eternal God, of one substance with the Father, took man’s nature in the womb of the blessed Virgin; so that two whole and perfect natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one person, never to be divided; whereof is one Christ, very God and very Man, who truly suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, to reconcile his Father to us, and to be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for actual sins of men (Articles of Religion, Article II).

Is Bigham-Tsai really saying that it is not important for United Methodists to agree with our doctrinal standards’ shared understanding of who Jesus is?

Given Article II’s statements, it is difficult to understand how a United Methodist bishop could state that God was not incarnate in “particular flesh.” How can it be said that “God became incarnate in a culture, but not one culture?” God was born of a virgin Jewish mother in Bethlehem at a known historical time. He lived and died as a practicing, devout Jew. His message and his life were in continuity with the Jewish Old Testament and in fulfillment of it. All of this took place within one person in one particular culture.

Yes, Jesus has relevance to every person and every culture, but God’s presence was made manifest in the particularity of one person and one culture. Without that bedrock understanding, we have no historical basis for interpreting the “Christ event” or its application to our own lives and culture.

Bigham-Tsai’s statements illustrate very well what is meant by the “big tent” approach to United Methodism. It gives the impression that United Methodist leaders do not view the doctrinal standards as actual standards, but suggestions or guidelines, to be disregarded whenever they do not “make sense” or are judged to be not helpful.

The Book of Discipline is very specific about the role of a bishop:

To lead and oversee the spiritual and temporal affairs of The United Methodist Church which confesses Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, and particularly to lead the Church in its mission of witness and service in the world. … To guard, transmit, teach, and proclaim, corporately and individually, the apostolic faith as it is expressed in Scripture and tradition, and, as they are led and endowed by the Spirit, to interpret that faith evangelically and prophetically.

By its very nature, this “big tent” excludes traditionalists who believe there are certain doctrinal propositions that are essential to Christianity. We believe the faith defined in the Articles of Religion and Confession of Faith. Without these doctrinal understandings, we do not have Christianity, but some other religion loosely based on Christianity.

Delegates at the North Central Jurisdictional Conference were aware of these doctrinal questions regarding Bigham-Tsai, yet elected her the first bishop in this year’s class. That can be viewed either as an indifference to doctrine or the adoption of a doctrine-less United Methodism. In any case, it speaks volumes about the theological direction of the future United Methodist Church.

Expanded Disobedience

To great fanfare, the Western Jurisdiction elected a gay man who recently married his male partner. This election carries on the precedent the same jurisdiction set by electing Karen Oliveto as bishop in 2016, who is married to another woman. Cedric Bridgeforth was elected even though the Judicial Council ruled that Oliveto’s consecration was contrary to church law and that her standing as a clergyperson must be brought up for judicial review (it never was).

Additionally, the Northeastern Jurisdiction came close to electing as bishop another gay man married to his male partner, Jay Williams. At one point, Williams was within 20 votes of having enough to be elected.

It appears that, for many delegates, the requirements of the Discipline are to be disregarded when they do not line up with one’s ideological commitments. One episcopal candidate made the comment that change comes from the bottom up, and that rules are often disregarded by the grass roots before they are changed formally by the legislative body.

The expanded disobedience is also seen in the fact that all five jurisdictions passed a resolution that affirms a moratorium on complaints surrounding sexual orientation, discourages pursuing complaints against clergy around their sexual activity or against pastors who officiate LGBTQIA+ weddings, and supports the election of bishops who uphold these aspirations.

Questions of law were asked in at least two of the jurisdictions hoping the Judicial Council will declare the resolution null and void because it encourages disobedience to the Discipline. No matter what the Judicial Council rules, the resolution indicates the overwhelming sentiment of U.S. delegates, as well as their disregard for what the General Conference has enacted in the Discipline. (The text of this resolution and two other important ones may be read at the Northeastern Jurisdiction Conference report, starting on page 25.)

In the next Perspective, we will project the implications the jurisdictional conferences have for the future of United Methodism and the role of traditionalists.

This article was originally published by Firebrand and is reprinted with permission. The full article may be read at: Firebrandmag.com.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president. of Good News.

by Steve | Nov 10, 2022 | In the News

Methodist Heritage: Spirit May Join Many Protestants

By Louis Cassels, United Press International

April 6, 1967

Published in The Ledger & Times (Murray, Kentucky)

The ecumenical spirit has persuaded Protestants and Catholics to accent one another as brothers in Christ.

Perhaps it can now achieve a similar miracle within the Protestant family by overcoming the antagonism and mutual contempt which have so long characterized relations between liberals and fundamentalists.

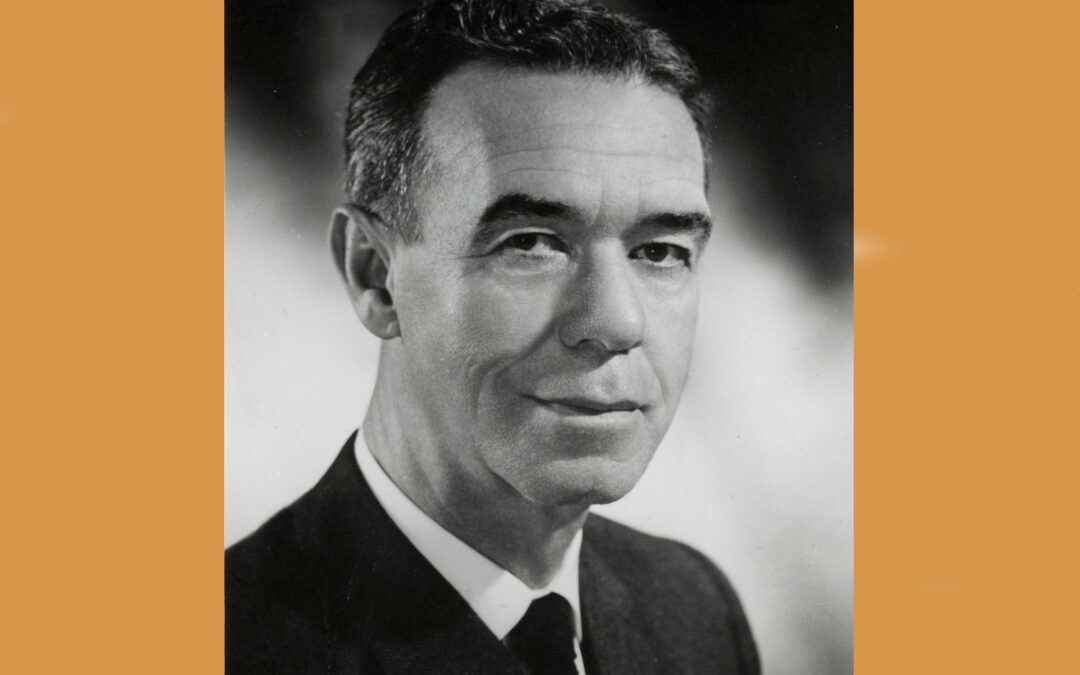

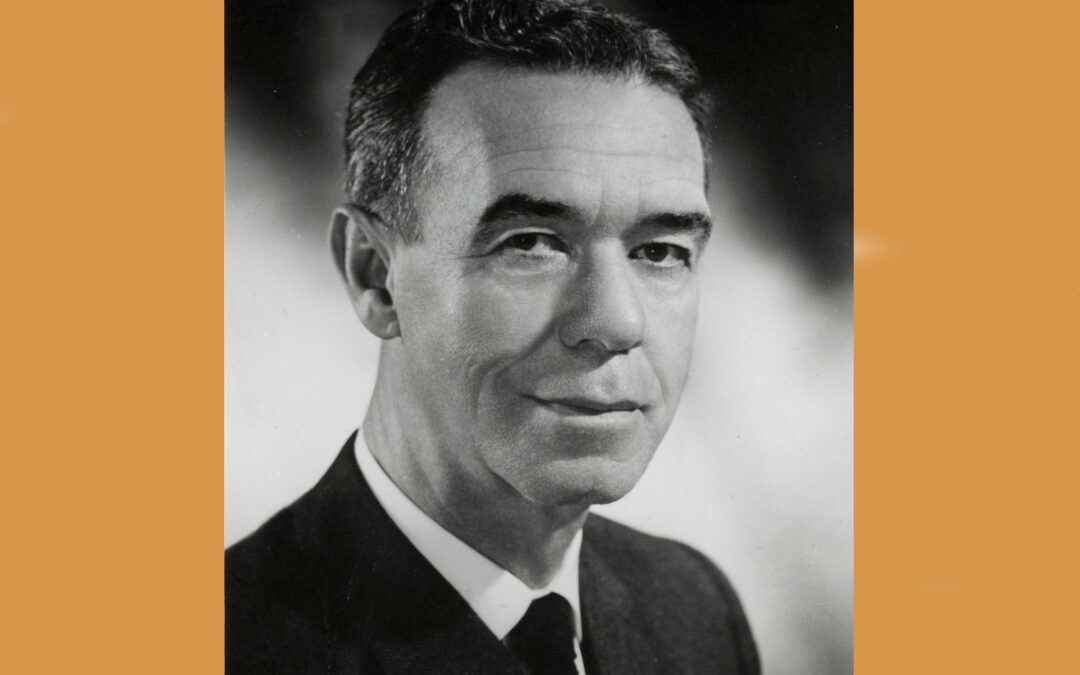

That hope was voiced this week by a prominent Protestant liberal Methodist bishop Gerald Kennedy of Los Angeles.

He contributed the lead article to a new magazine called “Good News” which was launched to provide a forum for evangelical or fundamentalist views in the Methodist Church.

“I am convinced that the main obstacle which faces us is not our differences, but the spirit in which we hold them,” said Bishop Kennedy.

“I have known some fundamentalists so narrow and bitter that it was impossible to talk to them … I have also known liberals who were so dogmatic and unbending that they could put the fundamentalists to shame.”

Bishop Kennedy acknowledged that “it is hard for a man with a great conviction to believe that a man who differs with him is honest.

“But this is one of the miracles which Christ works for us, and we ought to pray that he will touch us with his grace….

“We need each other Instead of merely putting up with somebody who is different than we are, let us thank God that he gives us an authentic witness from the other side of the hill.”

Is Grateful

As a liberal, he said, he is grateful to fundamentalists for their “emphasis is on the unchanging and eternal verities of our faith.”

He asked fundamentalists in turn to respect the Christian motivation of liberals who “feel so strongly about the relevancy of the church that they want to find ways to make it speak to the modern world.”

######