by Steve | Mar 21, 2023 | In the News, March/April 2023

By Ryan Danker —

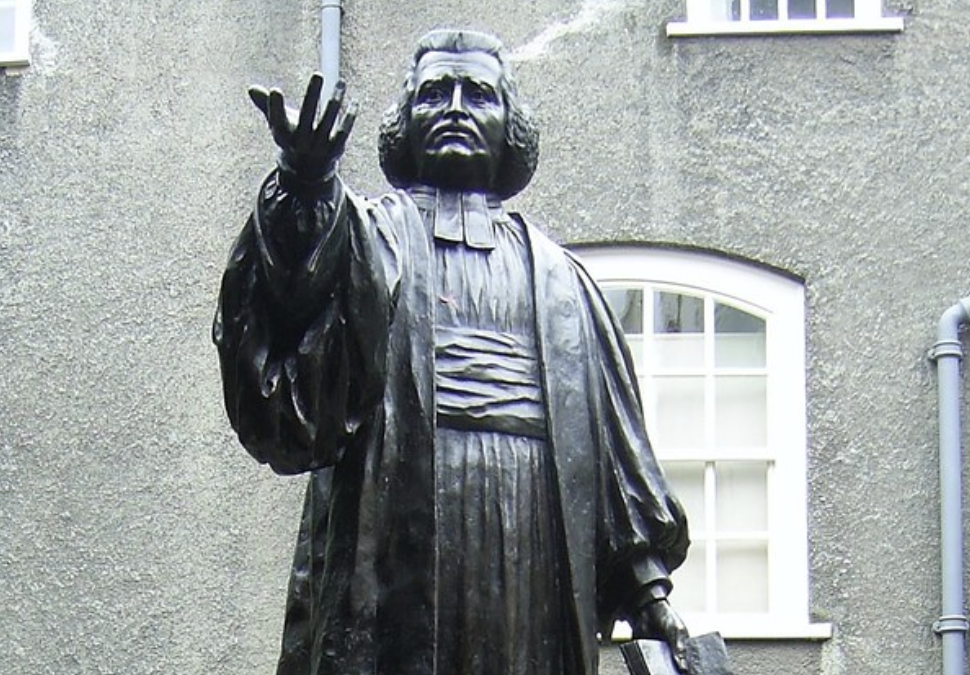

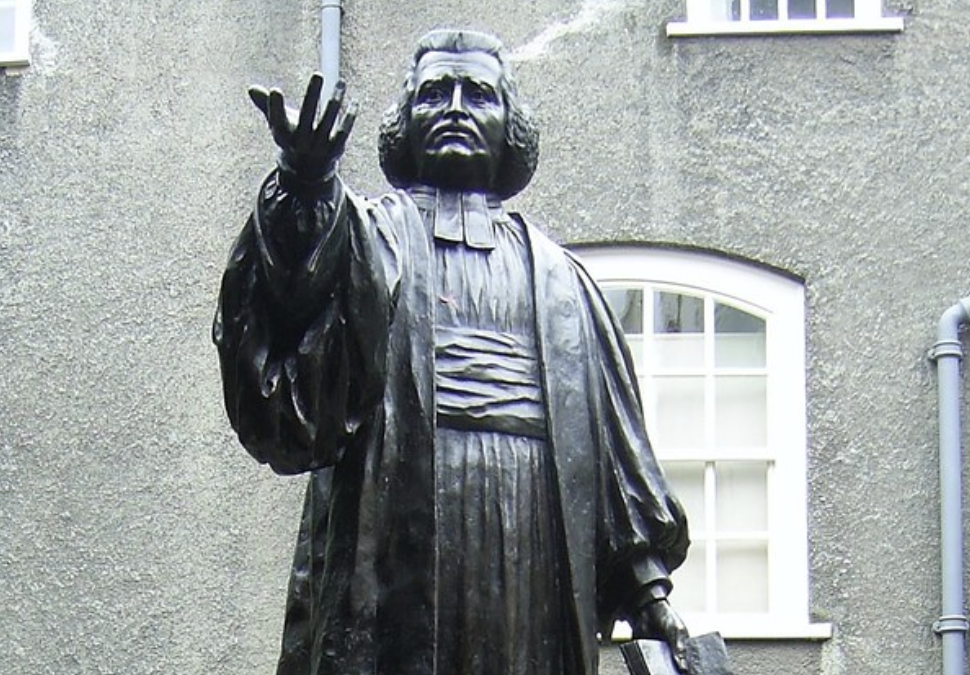

We all know the words of his hymns. For anyone in the Wesleyan movement and many beyond, his words speak to our experience of conversion, assurance, and even sanctification. Of course, I’m not talking about John Wesley. I’m talking about his younger brother, Charles.

Charles Wesley’s words quickly became the poetic vehicle of the Wesleyan revival. They linger in the mind, and even in the heart. They include: “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing,” “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling,” “O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing,” “Jesus, Lover of My Soul,” “Soldiers of Christ Arise,” and so many others. He wrote nearly 9000 poetic works.

As the message of the Wesley brothers and so many other leaders during the Evangelical Revival spread across the Atlantic and even farther, it was the hymns that carried the message with ease. The early Wesleyans carried their experiences, of course. They knew the dramatic experience of the new birth. Their hearts had been warmed by God’s assurance. Many could testify to the cleansing of Christian perfection. But even if they couldn’t quote one word from John, they could sing about their experience and of the love of God by heart using the words of Charles. In many places around the world today, many Christians can do the very same.

Yet apart from being the younger brother and a hymn writer, the average Wesleyan believer today knows very little about Charles Wesley the man. It often comes as a surprise that he wasn’t a good singer. Or that he never wrote a line of music. Even less is known about his family life and his adamant attachment to the Church of England, something his brother also maintained but with less regularity. If John was the cool organizer, Charles was the emotional artist. Apart from God, John’s first love was the Methodist movement. Apart from God, Charles’ first love was his wife and children, followed very closely by the Church. The brothers often bickered even if they often collaborated. Charles was like his father, and John like his mother. It’s a very complex story. And Charles can also be seen without his brother.

Like so many Wesley children, Charles was born in Epworth, the small Lincolnshire town where his father served as the incumbent of the parish church, St. Andrew’s. It’s thought that he was named after King Charles I, the great high church martyr. The execution, or martyrdom, of the King haunted the political and social imagination of the England that Charles Wesley knew throughout his life.

Charles was the third and youngest boy born to Samuel and Susanna Wesley who lived to adulthood. Nine of the children lived. Many died. This was common in the eighteenth century, but its commonality did not lessen the heartbreak felt by parents and families. Charles and his wife, Sarah, would experience the same grief many times in their own life together.

But the story is told that Charles was born sickly, or at least that he needed to be wrapped in blankets and kept by the fire to stay warm. He was born in December, after all. Charles did have some health problems throughout his life, but even these have been overblown simply because he had less energy than his overly-energetic brother. We do know of a toothache that he suffered in Boston in the late 1730s. The prescribed treatment was tobacco, which he tried. It made him sick to his stomach and may have distracted him for a bit, but obviously it didn’t work. He never tried tobacco again.

Charles grew up in a home filled with women. His oldest brother, Samuel, Jr., was out of the house by the time he was born. John went to Charterhouse School in London when Charles was six. So he and his father lived in Epworth with his mother, Susanna, and the six Wesley daughters. When he did go off to school, he went to Westminster. It was there – in the shadow of that great Abbey church, the site of coronations and the graves of the monarchs all around him – that he studied and where he became particularly close to Samuel Wesley, Jr. and his wife Ursula. Samuel worked at the school. Given the age difference between the two brothers, their relationship at this point was more like parent and child. The letters between Charles and his brother and his wife are very sweet. He refers to them as “my best friends.”

Like his father and his older brothers, Charles “went up” to Oxford and studied at Christ Church. It is here that the close association between Charles and John begins to form, although at first it wasn’t mutually desirable. John was a fellow, a tutor, at Lincoln. And at this time, tutors at Oxford were more than simply educators, they often encouraged the spiritual as well as educational development of their students. John tried to play this role with Charles, who did not eagerly welcome it.

All of the Wesley children were raised in the Christian faith. With John and Charles in particular, though, they experience what might be called key spiritual awakenings that continue to shape them throughout their lives. For Charles, the first was a turn toward a more serious Christian commitment in the face of a deist scare in Oxford that flared up in 1729. Two students were eventually expelled from Magdalen the next year, but the university – perhaps over-reacting – went into a full-blown defense of orthodoxy, with statements from deans, sermons, and a commitment to rid the university of the heresy. Charles Wesley was caught up in all of this fervor and dedicated himself to a stricter religious life in its wake. It is out of this that he joins with other students, and eventually his brother, and creates what will become the Holy Club, or the first rise of Methodism.

John had taken a “turn toward seriousness” earlier with his study of the Church Fathers and the Caroline Divines. Now the brothers were equally serious about their faith and it blossoms as they begin their life-long project to restore “primitive Christianity.” This is key to understanding the Wesley brothers and their efforts. Even when they disagreed, they were aiming at this standard and its restoration. Their efforts were not meant to create anything new, but to restore the old. This is what they thought they were doing when they travelled to Georgia to serve as clergy in the new colony.

At the beginning of the Revival, Charles is a different figure than he would be later. There seems to have been something of a tug-of-war between his emotional side with its desire for experiential Christianity and the traditions and ecclesiastical world of Anglicanism in which he was formed. The mature Wesley would come to see that his experiences needed to be grounded in tradition in order to avoid self-centeredness and being blown around by every wind of doctrine. But in the late 1730s – and not because of that tobacco in Boston – he was caught up in the emotive experience of the trans-Atlantic revival. This was yet another spiritual turning point for Charles.

Being caught up in the great sweep of the Spirit happened to many of the key figures that we know in Evangelicalism today. First, it struck George Whitefield in 1735. Later, it would catch up the Wesley brothers, Selina Huntingdon, John Newton, William Romaine, Francis Asbury, Charles Simeon, and so many others.

I think it’s a misinterpretation to say that Charles Wesley became a Christian when he had what he called his “Pentecost” experience in May of 1738. The journal account of his evangelical experience reads much more like an experience of assurance. He knew in his bones that he was a child of God. Strangely enough it came by way of Charles’ confusion when he was sick. He heard the voice of God when in fact it was the maid. Regardless, it changed him. It didn’t make him a hymn writer or poet, but after this experience his poetry carries both his experience and his theology to the masses. And the hymns pour out of him. Marking the year’s anniversary of his Pentecost experience, Wesley wrote “O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing” including the words:

On this glad day the glorious Sun

Of Righteousness arose;

On my benighted soul He shone,

And fill’d it with repose.

Following his experience he also began to follow his brother in the creation of the Methodist system of societies, classes, and bands, all with the intention of reviving the Church and spreading scriptural holiness. He even itinerated during this period, traveling and preaching. And writing hymns.

During the middle part of the century, Charles produced a number of hymn collections. In 1739, he published the

first edition of Hymns and Sacred Poems, a collection that he would revise and expand many times over. In 1745, he published Hymns on the Lord’s Supper, which is perhaps the greatest Wesleyan contribution to Eucharistic theology. The collection strongly points to the reality of Christ’s presence in the bread and the wine. At times, Charles is quite blunt about it while maintaining the mystery of it, a mystery he wrote that not even the angels could comprehend.

O the depth of love Divine,

Th’ unfathomable grace!

Who shall say how bread and wine

God into man conveys!

How the bread His flesh impart,

How the wine transmits His blood,

Fills His faithful people’s hearts

With all the life of God!

Additional collections would continue to be published including among others: Nativity Hymns (1745), Resurrection Hymns (1746), Ascension Hymns (1746), Hymns for Children (1763) and his ultimate collection, A Collection of Hymns for the People Called Methodist (1780). However, not all of his poetic output was intended for singing. When he and Sarah lost a child, Charles communicated his grief through poetry in his Funeral Hymns (1759). One stanza will provide a glimpse of his emotion, that of a father in grief at the loss of his son:

Mine earthly happiness is fled,

His mother’s joy, his father’s hope:

O had I died in Isaac’s stead!

He should have lived, my age’s prop,

He should have closed his father’s eyes,

And follow’d me to paradise.

The poetry that he wrote as a father is heart wrenching at times. At others, it’s quite practical and quotidian, such as his hymn “For a Child Cutting His Teeth” in Hymns for a Family (1767), which although about teething is also highly theological.

Love for the poor, especially those who are in prison, comes out in his hymns. Charles believed very firmly in prison reform. And so in many respects, we can read the line from “And Can It Be” as referring to both a spiritual freedom, but also a tangible one when we sing “my chains fell off, my heart was free, I rose went forth and followed Thee.” This love for the least was also seen in his work with those who were condemned to the death penalty. Like other Methodist leaders at the time, he often preached to them even as they rode to their execution. Given his love for the poor, later critiques of Charles claiming that he lived too well seem odd. He did, however, have a comfortable income from the sale of hymn collections – something necessary to gain permission to marry his beloved Sarah – and he was comfortable amongst the wealthy, particularly Lady Huntingdon.

He wrote polemical poetry against Calvinists, the second Jacobite rebellion, and even against his brother, John, when he thought that he was leaning toward separation from the Church in 1755 with his widely published Epistle to Mr. John Wesley including a reminder to his brother that the Methodists are just a part of the Church, not the whole: “The Church of Christ and England – is But One!”

So why did he stop itinerating? Many modern evangelical thinkers have said that he did this because he got married and settled down. Literally. But this, too, is a misinterpretation of the story. It played a part, but imposing contemporary evangelical concepts of family life on the eighteenth century isn’t a good idea. Instead, Charles probably stopped itinerating a few years after his marriage because he saw the separatist trajectory of Methodism and that much of it would eventually depart from the Church of England. He couldn’t participate in that separation with integrity. Methodist interpreters often struggle to understand this aspect of Wesley’s thought, both then and now. Charles was the conservative at the center of the Wesleyan wing of the Evangelical Revival.

His marriage to his wife Sarah and the birth of their children was the greatest joy of his life. The letters between he and Sarah are warm and loving. They read like the letters between John and Abigail Adams, also of the same period. Much of their married life was spent in Bristol in a four-story townhome near the center of town. In a letter from 1760, Charles wrote to his wife recalling both his Pentecost experience and his marriage. Writing of their life together he states, “Eleven years ago He gave me another token of His love, in my beloved friend.”

This was in stark contrast to John’s romantic life. But Charles didn’t always help his brother in this regard. He married off John’s likely fiancé when John was off on a preaching tour of Ireland because he didn’t think they were of similar social standing. The letters between the brothers in the aftermath of this episode are some of the most emotional we have between them. John would enter an unfortunate marriage in 1751.

Differences over the trajectory of Methodism would strain the brothers’ relationship. And in the autumn of 1784 it was challenged more than anything up to that point when John declared himself “a New Testament bishop” and ordained Thomas Coke as superintendent and Thomas Vasey and Richard Whatcoat as presbyters for the Methodists in America. Charles was in Bristol when the ordinations took place. John knew better than to even tell him about them. Some of the poetic lines that Charles wrote in the aftermath are a combination of wit, frustration, and anger:

So easily are Bishops made

By man’s, or woman’s whim?

W[esley] his hands on C[oke] hath laid,

But who laid hands on Him?

Charles had particular venom for Coke, whom he was convinced had duped his brother into this action. Amazingly, John’s ordinations did not sever him from the Church. He died in good standing as a presbyter within it. However, the relationship with his brother was never the same.

For many decades, Charles had a difficult relationship with many of the lay preachers of Methodism as they clamored for ordination outside of the Church. Some he was able to recommend for holy orders. Many bishops were hesitant to ordain Methodists. In Samuel Seabury, however, the first bishop of the Episcopal Church, Charles found a true colleague.

Toward the end of his life, Charles committed himself to seeing Methodist preachers in the newly independent United States ordained in the emerging Episcopal Church. In fact, he wrote the required recommendation letters for ordination on behalf of Joseph Pilmore in 1785, one of the earliest leaders of American Methodism. Pilmore was ordained by Seabury and planted evangelical Episcopal parishes in and around Philadelphia.

Charles and Sarah moved to London later in life. And it was there that he died in 1788 at the age of 8o. As he and Sarah lived in the London parish of Marylebone, he insisted that he be buried in the consecrated cemetery of his local parish. His body was to be carried to its final resting place by six priests of the Church of England. To his dying breath, he believed in the historic witness and structures of the Church and that they give space to experience, ensuring that it is guided by the Christ who is found in Scripture and the bishops and priests appointed to his church.

Looking at Charles Wesley’s long and productive life, three things are noteworthy within the space we have here. First, he was a man who loved many, particularly his wife and children, particularly his family, and even his brother with whom he had the greatest impact and the most passionate disagreement. The story is told of John after Charles’ death falling into tears at a Methodist meeting at the words of the hymn: “My company before is gone, and I am left alone with Thee.” The affection between the brothers was real. Secondly, and related to it, is Charles’ gift for friendship. This was what his wife Sarah said was his greatest gift. Charles was a friend to many, even across differences. Finally, but definitely not the least, is the passion that Charles had for God, for the message of salvation, and for his Savior. We see this so clearly and so beautifully in his hymns. This love drove his poetic work. And we are the benefactors of that gift. With saints below and saints above, because of Charles Wesley we can sing the praises of God in words both profound and sublime. We can sing of that transforming love that makes us whole, even in the words of one of his greatest offerings:

Finish then Thy new creation,

Pure, and spotless, let us be,

Let us see Thy great salvation,

Perfectly restored in Thee:

Changed from glory into glory,

Till in heaven we take our place,

Till we cast our crowns before Thee,

Lost in wonder, love, and praise!

Ryan Nicholas Danker is the Director of the John Wesley Institute in Washington, DC, as well as the president of the Charles Wesley Society. Dr. Danker is the author of Wesley and the Anglicans: Political Division in Early Evangelicalism and co-editor of The Next Methodism and Assistant Lead Editor of Firebrand Magazine.

by Steve | Mar 21, 2023 | In the News, March/April 2023

By Jason Vickers —

For God so loved the world. So begins the Gospel of Jesus Christ. God does not need the world. God in no way depends upon the world. The world’s existence is sheer grace. It is a fitting expression of God’s loving nature. God loves the world – so much so that the Word became flesh and dwelled among us, shining light in the enveloping darkness (John 1:1-5).

But the Gospel is not finished. It also declares that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us (Romans 5:8). God does not love the world because we are righteous. God loves the world despite our sin and unrighteousness – so much so that Christ suffered and died in order to reconcile us to God and make us ministers of reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5:18).

Central as it is in the drama of redemption, the cross is not the final word of the Gospel. God’s love for the world is further displayed in Christ’s resurrection, signaling as it does God’s power over death and God’s resolve to renew God’s good creation. But God does not raise Jesus in order to take him away, leaving us powerless in the face of sin and death. Even now, the risen Lord is present in the sacramental life of the church, forgiving, comforting, and sanctifying us. God loves us and has mercy upon us – so much so that God provides us with means of grace by which the Holy Spirit joins us to the crucified and risen Lord. Incorporated into Christ’s body, the power and promise of the resurrection enable us to weather the storms of life and to live together as a sign of God’s love for the world (1 Corinthians 12:27).

Gloriously good news that it is, even Christ’s resurrection does not exhaust the Gospel. Tragically, sin and death continue to have their way in the world. Brokenness and hostility are everywhere. The righteous suffer, and the wicked prosper (Psalm 73:12-14). Warring and violence persist. Amid the flickering light, a deep and encircling darkness remains, just as the Lord promised (Matthew 24:6). Fortunately, the Gospel declares that Christ will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead (2 Timothy 4:1). God’s love for the world will have the last word – a word of welcome for those who persevere, and a word of condemnation for those who oppose the cause of Christ. And his kingdom will have no end (Luke 1:33).

All of this is the Gospel; it is the faith once delivered to the saints (Jude 1:3). With the help of the Holy Spirit, we cling to this good news in faith, hope, and love. But we are also called to proclaim it throughout the world. We are called to proclaim that God is love (1 John 4:8b); that God is rich in mercy (Ephesians 2:4); and that God will sanctify us and preserve us blameless at the coming of our Lord (1 Thessalonians 5:23-24). We are called to proclaim that, with God, all things are possible (Matthew 19:26). We are called to proclaim that Christ has disarmed the authorities and powers, including death itself, and that we therefore have nothing to fear (Colossians 2:15).

The world desperately needs to hear the Gospel. The world needs to hear that God is love and that God has not abandoned God’s good creation. The world needs to hear that, because of Jesus Christ, we do not have to be slaves to sin (Romans 6:20-22). We do not have to despise our neighbors or horde our resources. We do not have to be captive to anger and bitterness and shame. Nor are we doomed to cynicism and despair. But for the world to hear the Gospel, someone must proclaim it.

As the Apostle Paul wrote, “How are they to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him? And how are they to proclaim him unless they are sent?” (Romans 10:14-15).

The proclamation of the Gospel is central to the church’s mission. It is what we are called to do. We come together for worship and fellowship, but we are ultimately sent out to bear witness to the Gospel in our neighborhoods and workplaces and to the imprisoned and the infirmed. We receive the body and blood of Christ so that we might be Christ’s body and blood for the sake of the world. And this is why disagreement and disunity among Christians is so deadly. In our disunity, we risk losing sight of the high calling to which we have been called (Ephesians 4:1). Caught up in our disputes with one another, we lose sight of the very world that God so loves. In turn, the world sees our disunity, shakes its head in disbelief, and sinks ever deeper into the darkness.

Disagreement and disunity are realities of church life. Across the centuries, the church has endured many seasons of separation and schism, most notably, the Great Schism of 1054 and the Protestant Reformation. Methodism itself is the result of a separation from the Church of England. Wesleyan-holiness churches separated from Methodism. And so on. Of course, the fact that there have been many divisions and schisms across the centuries does not justify disunity. Unity in the body of Christ is something we should all earnestly seek for the sake of the Gospel. Jesus himself prayed that we would all be one, even as he and the Father are one (John 17:21). In the meantime, which is to say in the midst of the painful reality of disunity, we must do all that we can not to lose sight of the world that God loves – a world inhabited by drug dealers and sex traffickers and by people whose lives have been broken by addiction and abuse.

In the months and years ahead, Methodist clergy and laity will continue to make decisions about their futures. Many will remain in The United Methodist Church. Many will join the newly founded Global Methodist Church. Some will join other existing denominations. Others will choose to become independent. Once decisions are made, the only question that will remain is whether we will allow ourselves forever to be defined by our disagreements with one another. To the extent that we do, the cause of the Gospel will suffer, and with it the world that God so loves.

If we are to be salt and light in the world, then we must both understand the Gospel and be able to communicate it effectively to a world that views the Gospel as so much folly. These are monumental tasks – understanding the Gospel and communicating it effectively. Each requires the illuminating power of the Holy Spirit. We all need the Spirit’s help more fully to understand the mysteries into which we have been baptized. And we all need the Spirit’s help to communicate the Gospel in such a way that the world can hear it as good news and respond to it in faith.

Fortunately, the Holy Spirit has not left us bereft of resources to help with these tasks. On the contrary, the Spirit is a generous giver of gifts to aid the church in both understanding and communicating the Gospel for the sake of the world. For starters, there is the gift of Holy Scripture, the foundation of all true teaching concerning God and all things in relation to God. But that is not all. The Spirit also gives the gift of worship and sacraments, by which we glorify God, die and rise with Christ, and experience sanctifying communion with our Lord. Beyond all of this, the Spirit gives us the gift of doctrine and theology, as well as the gift of great teachers who can help us to contemplate the mysteries contained therein. There are also the gifts of leadership and the offices of ministry, including bishops, elders, and deacons – offices essential for the maintenance of the sacramental life of the church, for ordination, and for discipline. The Spirit also gives innumerable gifts to the laity, such as hospitality, prayer, care-giving, and service. There are also gifts of language and music, poetry and art.

In the Christian East, icons and iconography are received as gifts of the Spirit – the Gospel written in gold. All these things, and more besides, are best understood as means of grace by which we come to know and love God and communicate God’s love for the world.

Understanding the Gospel and being transformed by it, let alone communicating it effectively to the world, requires a deep immersion in all the means of grace. We need to know the Scriptures inside and out. We need to internalize the Creed, and we need a deep knowledge of our essential doctrines. We must also be able to convey the vision of God and salvation embedded in Scripture, Creed, and doctrine in a wise and winsome way. We must know when to reach for the Gospel of John and when to deploy the book of Job. We must preach with prophetic passion, calling both the church and the world to repentance, and we must help people experience the healing power of Holy Communion.

Tragically, disunity and schism threaten to rob us of the very means of grace on which our life with God depends. They do so in two ways. First, in the midst of division and disunity, we can turn gifts of the Holy Spirit meant for our sanctification and to aid in the proclamation of the Gospel into weapons with which we pummel our enemies’ positions. This is a danger that people on all sides of the current disagreements in Methodism must be on guard against. When we turn to Scripture and doctrine primarily to fund our arguments with one another – whatever those arguments might be about – we risk losing sight of the world that God so loves. The primary purpose of the means of grace that the Spirit gives to the church is to rouse the world to faith and to enable all to live in hope and love rather than vengeance and fear.

The second way that division and schism can rob us of the means of grace so crucial for our sanctification and for the effective proclamation of the Gospel may be even more dangerous than the first. In any schism, those who disaffiliate from an established church will be tempted to set aside gifts of the Spirit that, in the midst of division, they have come to see as problematic or harmful. For example, in the Protestant Reformation, many were quick to discard gifts of the Spirit that their ancestors in the faith had experienced as means of grace for sanctification and proclaiming the Gospel. The list of sacraments was reduced to two, often with little thought as to what the long-haul consequences of such a reduction might be. In addition, visual representation of the Gospel in sacred art and images was rejected, leading to a devastating wave of iconoclasm across Protestant Europe, and an utter disregard for the ways in which visual images can aid people in coming to faith, in the journey of sanctification, and in the communication of the Gospel to the world.

In any division that ends in separation, those who disaffiliate from an established church will have to make crucial decisions about what resources are essential for helping people come to faith, for sanctification, and for the effective proclamation of the Gospel. In the current division within Methodism, both those who affiliate with the Global Methodist Church and those who become independent will have to make such decisions. As they do, it would be wise to remember that all the gifts of the Spirit to the church have at one time or another been subject to misuse and abuse. However, the fact that something has been misappropriated does not mean it is not a gift of the Holy Spirit to the church. For instance, many Methodists believe that the episcopacy and theological education have been subject to corruption and abuse in recent years. This does not mean that episcopacy and theology are not gifts of the Holy Spirit that, when rightly received and deployed, are crucial for understanding, receiving, and proclaiming the Gospel. On the contrary, what is now needed is a deliberate re-connecting of all the means of grace, including episcopacy and theology, to these ends.

In the meantime, the world is waiting.

Jason Vickers is Professor of Theology at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, and the incoming William J. Abraham Chair in Wesleyan Studies at Baylor University, Waco, Texas. Dr. Vickers is the editor of the Wesleyan Theological Journal and the author or editor of ten books, including A Wesleyan Theology of the Eucharist and the Cambridge Companion to American Methodism.

by Steve | Mar 21, 2023 | In the News, March/April 2023

By Steve Beard —

Over the last 40 years, one of the most popular and memorable modern day hymns is “Majesty, Worship His Majesty” written by Jack Hayford. Congregations from all denominations around the globe have sung it with reverence and gusto. It is included in The United Methodist Hymnal, as well as the new collection titled Our Great Redeemer’s Praise.

On Sunday, January 8, 2023, Hayford died at the age of 88. He was a beloved clergyman, prolific songwriter, and sought-after mentor. “Today, we mourn his loss but celebrate the homecoming of a great leader in God’s kingdom,” announced Hayford’s ministry. “We know that this great servant and worshipper is now experiencing the greatest worship service of all.”

For thirty years, Hayford was the pastor of The Church on the Way in Southern California. To an entire generation of church leaders, he was an irreplaceable bridge-builder between Pentecostal/charismatic believers and the wider ecumenical Church.

Fittingly, Hayford’s international notoriety sprung from his memorable worship song. “Majesty” was written in 1977 while he and his family were vacationing through England during the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth. As they roamed through historic Blenheim Palace, the birthplace and ancestral home of Winston Churchill, Hayford was inspired by the regal surroundings.

Thinking from the heart, he became mindful “that the provisions of Christ for the believer not only included the forgiveness for sin, but provided a restoration to a royal relationship with God as sons and daughters born into the family through His Majesty, Our Savior Jesus Christ.”

As he was driving around England, Jack asked his beloved wife Anna to write down the words and melody. “So exalt, lift up on high, the name of Jesus/ Magnify, come glorify Christ Jesus, the King.”

Hayford reports that he was filled with a powerful “sense of Christ Jesus’ royalty, dignity, and majesty …. I seemed to feel something new of what it meant to be his! The accomplished triumph of his Cross has not only unlocked us from the chains of our own bondage and restored us to fellowship with the Father, but he has also unfolded to us a life of authority over sin and hell and raised us to partnership with him in his Throne – Now!”

In addition to his role as a pastor, Hayford was a Bible teacher, author of 50 books, writer of more than 500 worship songs, editor of the Spirit-Filled Life Bible, denominational leader of The Foursquare Church, and founder and chancellor emeritus of The King’s University (now located in the Dallas area).

“Jack lived in a God-charged, open universe that challenged the reductionism of the modern world,” observes Dr. S. David Moore in Pastor Jack, a 2020 biography of Hayford. “At a time in which reality came to be defined in purely naturalistic terms, dismissing the supernatural as antiquated folklore, Jack Hayford’s life and ministry offered a recovery of the biblical world, a world in which God is active and present in his creation.” His teaching and leadership often made memorable impressions on non-Pentecostal believers.

“I’ll never forget the wonderful way Jack Hayford led us in a concert of prayer at the Promise Keeper’s Million Man March in Washington, D.C., in 1997,” recalled Dr. Stephen Seamands, professor emeritus of Christian Doctrine at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. “He was such a Christian statesman and role model for me. In his book, A Passion for Fullness, he writes, ‘Let us commit ourselves wholeheartedly to a supernatural ministry disciplined by a crucified life.’ That summed up what I was striving for so well for me.”

In addition to his teaching on the work of the Holy Spirit, Hayford’s thoughts on worship are an essential factor in comprehending his ministry. “In both the Old and New Testaments,” he taught, “God’s revealed will in calling his people together was that they might experience his presence and power – not a spectacle or sensation, but in a discovery of his will through encounter and impact.”

Hayford taught extensively about heartfelt worship being far more dynamic than what is sometimes mistaken as merely the order of a service in a church bulletin. “In my experience, theological discussions about worship tend to focus on the cerebral, not the visceral – on the mind, not the heart. ‘True’ worship,” he wrote, “we are often taught, is more about the mind thinking right about God (using theologically correct language and liturgy), rather than the heart’s hunger for him.

“But the words of our Savior resound the undeniable call to worship that transcends the intellect: ‘God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth’ (John 4:24). We’ve been inclined to conclude that mind is the proper synonym for spirit here, but the Bible shows that heart is a better candidate. ‘In truth’ certainly suggests participation of the intellect in worship, but it is inescapably second – and dependent upon the heart’s fullest release first.”

Hayford concluded, “The exercises of our enlightened minds may deduce God, but only our ignited hearts can delight him – and in turn experience his desire to delight us.”

As a church leader, Hayford was faithfully committed to biblical exposition, racial reconciliation, teaching on the Kingdom of God, praying for churches and leaders outside his own Pentecostal tradition, discerning the difference between “holy humanness and human holiness,” explaining the “beauty of spiritual language” (speaking in tongues), and maintaining irrevocable honesty in his heart.

“My commitment to walk with integrity of heart calls me to refuse to allow the most minor deviations from honesty with myself, with the facts, and most of all, with the Holy Spirit’s corrections,” Hayford believed.

Hayford saw “his private prayer life as the essential foundation of his ministry, and he deeply yearns to know and please God and live in radical dependence,” wrote Moore in Pastor Jack. “His journals are filled with prayers of confession, praise, and especially lament for his weaknesses and shortcomings. And yet almost always his journal entries end with grateful affirmation of God’s faithfulness to his promises.”

The Church on the Way was located only a few miles from the glamour of Hollywood and it attracted a handful of high-profile members of the entertainment industry. However, the congregation grew steadily without glitz or publicity stunts. Hayford’s appeal was built on his personal humility, integrity, and honesty.

“There is, in whatever one studies of Jesus, everything of humanity and nothing of superficiality; everything of godliness and nothing of religiosity,” wrote Hayford. “Jesus ministered the joy, life, health and glory of his Kingdom in the most practical, tasteful ways. There is nothing of the flawed habit of hollow holiness or pasted-on piety that characterizes much of the Christianity the world encounters.”

Authentic discipleship – to be “Spirit-formed” as Hayford called it – involves nurturing intimacy with God. In his relationship with Jesus, Hayford was committed “to seek him daily (1) to lead and direct my path, (2) to teach and correct my thoughts and words, (3) to keep and protect my soul, and (4) to shape and perfect my life.”

Hayford’s love and concern for clergy of all traditions earned him the title of “pastor to pastors.” Despite coming from a relatively small, classical Pentecostal denomination, his generous spirit had wide appeal.

“I have a shepherd’s heart,” Hayford said prior to his death. Whether he was teaching before 39,000 clergy in a football stadium or hosting a dozen pastors in his living room, Hayford etched a lasting impression on those whom he treasured so much. In a previous era of polarization and mistrust, Hayford stood out as a passionate worshipper and peacemaker. He left a robust legacy of vulnerability and devotion through living a life that was animated by the presence and love of God.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Steve | Mar 21, 2023 | In the News, March/April 2023

By Danielle Strickland —

I stole my first car when I was twelve years old. In family court, when my fate seemed to be incarceration, a leader from my church insisted I was going through a hard patch, but I could be sentenced to community service at a camp. The judge jumped at the opportunity.

But not even the intervention of kindness, the crisp, clean air of the woods, or the majesty of the natural world could snap me out of my downward trajectory. I’m bewildered and amazed that I lived through it. I can only surmise that the power of prayer and the grace of God, both undeserved but freely given, kept me alive.

I don’t remember a whole lot, but there are a few moments I can’t forget.

I remember the drive-thru where my uncle took out a bottle of vodka and topped off my Sprite, assuring me this would make a Happy Meal even better. I was eleven. He was bad. And I loved it. He fed me more than alcohol that day – he fed me the recipe of escape. Of addiction. A steady diet of lies is what I drank from that man. Those lies kept on feeding me.

I wanted to be bad. I didn’t want the consequences of my actions, but I also didn’t really mind them that much. I became drug-addicted, cold-hearted, and completely out of control.

That brought me to a day in court for over twelve charges. I had stolen another car. I had led the police in a high-speed chase around the city. I was with my partner who I had been forbidden to see by court order. I had robbed a store and injured the owner in an escape. I had damaged property. I had drugs on me and was high as a kite. The court wanted to try me as an adult or sentence me to the maximum for a young person – three years in a maximum-security prison.

On the inside, it did not matter to me if I lived or died. I was not at all remorseful. As the court was deciding if we would be released or held, the plaintiff called forward the man whose car we had stolen. His name happened to be Mr. Rogers. And even though my friend and I were handcuffed and facing jail time, we could not stop laughing. I mean seriously – Mr. Rogers!

My friend started singing “It’s a terrible day in the neighborhood.”

And even though the judge was ticked off, I said, “Boys and girls, can you say criminal?” And we both laughed.

They remanded me to prison because they believed I was a threat to society. They were right. Soon, I was in a holding cell in the basement of City Hall in downtown Toronto.

But then the guard let in a woman named Joyce Ellery, a member of my parent’s church. I rolled my eyes and cursed under my breath. I was not interested in the lecture or the invitation to change my ways. I couldn’t take the perpetual disappointment of my religious upbringing.

Joyce entered my cell and handed me a lawyer’s card – which is the kind of practical Christianity that brings tears to my eyes. And then she did something I did not expect. She hugged me. She wrapped her warm arms around my cold-hearted, drug-infused, bristling body. And what she didn’t do spoke volumes.

She didn’t lecture me. She didn’t scold me. She didn’t even advise me. She whispered in my ear while hugging my resistant teenage frame: “I love you.” That’s it. That’s all. That’s the whole thing. Then she nodded at the guard, who promptly opened the door for her to leave.

I was dumbfounded. But when that cell door closed, I heard the bang of finality. I was alone. I was stuck. I was lost. And then the most wonderful thing happened. Jesus showed up.

Was it a vision? A feeling? A trance? A tangible encounter with the divine? A metaphysical neurological brain experience? A drug trip? I have no idea. Here is all I know: Jesus showed up. I felt him. I sensed him. I heard him. I experienced him.

Jesus came with his arms open and wrapped me in his love. He whispered in my ear, “I love you.” And all the fear and pain, and shame and guilt, and hardness and badness started to loosen and leave, and I felt loved. Unconditionally loved.

It was like someone turned on a light inside of me and I could finally see that the place I was in was not good. That I didn’t belong there.

That encounter with Jesus did something that can never be undone. However, it did not make me magically better. Love made me alive, but it still left me human.

I was still addicted to drugs. I was still in prison. I was still stuck in cycles of thinking and living that would be very difficult to break. I was still captive to a lot of pain buried deep inside that would take decades to uncover and bury. But I was alive, I could feel, I could see, and I had hope.

I’m so thankful for Joyce. And Jesus. And even Mr. Rogers.

For that day truly was the most terrible, wonderful, beautiful day in the neighborhood.

Hope.

Danielle Strickland is pastor, author, and justice advocate based in Toronto, Canada. She is the author of several books and host of DJStrickland Podcast, ambassador for Stop the Traffik, as well as the co-founder of Infinitum, Amplify Peace, The Brave Campaign and the Women Speakers Collective. This article was excerpted from The Other Side of Hope by Danielle Strickland. Copyright © 2022 by Danielle Strickland. Used by permission of Thomas Nelson Publishing (www.harpercollinschristian.com).

She will be one of the plenary speakers at the Beyond These Walls conference April 27-29 at The Woodlands Methodist Church in The Woodlands, Texas.

by Steve | Mar 21, 2023 | In the News, March/April 2023

By Scott Sauls —

The book of Ecclesiastes is a confounding, long-hand essay written by a man who on the one hand has immeasurable power, wealth, possessions, feasting, and pleasure, and on the other hand cannot find happiness.

As I think about Ecclesiastes and all the other stories of prosperous women and men for whom life’s “rich blessings” have not delivered on their promises, I am also struck by Jesus’ admonishment to his disciples as they began experiencing “success” as the world defines it:

“The seventy-two returned with joy, saying, ‘Lord, even the demons are subject to us in your name!’ And he said to them…Behold, I have given you authority to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy, and nothing shall hurt you. Nevertheless, do not rejoice in this, that the spirits are subject to you, but rejoice that your names are written in heaven’” (Luke 10:17-20).

Did you catch that? When Jesus’ disciples came to him with news of their extraordinary strength and influence and success, his response was to say, “Do not rejoice…”

When God gives us success and loved ones and happy circumstances for a time, when he chooses to put the wind at our backs – by all means, we should enjoy the experience. But we mustn’t hang our hats on it … because earthly success, in all its forms, comes to us as a gift from God and is also fleeting. Our Lord is telling us not to allow appetizers to replace the feast, or a single apple to replace the orchard, or a road sign to replace the destination to which it points.

On this, C.S. Lewis provides essential wisdom in The Weight of Glory: “It would seem that Our Lord finds our desires (that is, our ambitions) not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased.”

No self-serving ambition has the ability to satisfy the vastness of the human soul made in the image of God. As Augustine aptly said, the Lord has made us for himself. Our hearts will be restless until they find their rest in him.

Lewis’ perspective, when we share it, can also safeguard us from what the famous playwright, Tennessee Williams, called “The Catastrophe of Success.” Williams understood that while things like momentum, influence, position, being known, and being celebrated are fine in themselves, none of these things can sustain us in the long run.

Reflecting on his instant success after the release of his blockbuster Broadway play, The Glass Menagerie, he wrote: “I was snatched out of virtual oblivion and thrust into sudden prominence… I sat down and looked about me and was suddenly very depressed… I lived on room service. But in this, too, there was a disenchantment… I soon found myself becoming indifferent to people. A well of cynicism rose in me… I got so sick of hearing people say, “I loved your play!” that I could not say thank you any more… I no longer felt any pride in the play itself but began to dislike it, probably because I felt too lifeless inside ever to create another. I was walking around dead in my shoes… You know, then, that the public Somebody you are when you ‘have a name’ is a fiction created with mirrors.”

Tennessee Williams’ story, as well as the story of every person who has experienced the anticlimax of getting to the end of the rainbow and finding that there is not a pot of gold there after all, confirms a universal truth for every human heart:

Only Jesus, whose rule and peace shall never stop increasing (Isaiah 9:7), can sustain us. Only Jesus, whose resurrection assures us that he is, and forever will be, making all things new, can fulfill our deepest desires and give us a happily ever after. Only Jesus can make everything sad come untrue (got that one from J.R.R. Tolkien). Only Jesus can ensure a future in which every chapter will be better than the one before (from C.S. Lewis). Only Jesus can give to us the glory and the soaring strength of an eagle (Isaiah 40:31). Only Jesus, whose name is above every name, and at whose name every knee will bow, can give us a name that will endure forever (Philippians 2:9-10; Isaiah 56:5).

Making much of his name is, then, a far superior ambition than making a name for ourselves. For apart from Jesus, all men and women, even the most ambitious and successful and strong, will wither away like a vapor. “People are like grass. The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of our God will stand forever” (Psalm 40:7-8).

Is the wind at your back? Don’t hang your hat there. Is the wind in your face? You can still rejoice, because in Jesus, your name is written in God’s book. And what could be better than that?

Scott Sauls is the pastor of Christ Presbyterian Church in Nashville and the author of numerous books. He has authored six books: Jesus Outside the Lines, Befriend, From Weakness to Strength, Irresistible Faith, and a Gentle Answer. His most recent book is called Beautiful People Don’t Just Happen. This article originally appeared on his website (scottsauls.com) and is reprinted here by permission.

by Steve | Mar 20, 2023 | In the News, March/April 2023

By Jenifer Jones —

Sharon Hill* is a storyteller. She recites passages of Scripture in an interactive way, inviting listeners to see themselves in the story and to experience the Jesus they are hearing about. She does this primarily among Muslims and among people who used to be Muslims and who are now believers in Christ. All of the stories are told orally, making it an ideal method for reaching out to those in locations where it might be dangerous to have a Bible. She also trains people to share the gospel through storying. In Central Asia, she taught a team that visits women who are trafficked and prostituted. The group members invited Hill to go with them into a brothel so that they could watch Hill’s example of storying in such a setting. What follows is Sharon’s retelling of the encounter.

•••

I’m in Central Asia in the middle of the night in a brothel. The team I was with had been there before. We walked in and my host said, “This is my friend. Her name is Sharon, and she’s a storyteller.”

We sat down at a little table with a few of the women. There were some men buying women behind me at the desk, passing money along, disappearing into the corridor.

In this culture, older people have nothing to do with the women in the brothel. The women wanted to know how old I was, and then they started to give me beauty advice. We were having the best time laughing and talking. God was building a rapport.

Finally, my friend said, “Well, would you like to hear one of her stories?” The women said, “Yes, yes, yes.”

One of the ladies at our table yelled at the madam who runs the brothel and said, “Turn off the television. We want to hear her story.”

I never know what story to tell until the moment arrives. I felt God saying that I should tell the Bartimaeus story. And I thought, Lord, these are all women. This is about a male beggar. Are You sure?

I said to the women, “Now put yourself into this story, as if you were there.”

“And so as Jesus and his disciples, together with a large crowd, were leaving Jericho, there was a blind man named Bartimaeus sitting by the roadside begging.”

I said, “So tell me what you think it’s like for him. Blind, begging, sitting by the roadside.” One lady started to tear up and wouldn’t make eye contact. She said, “Oh, I know how he felt. I was pushed down the stairs by a boy when I was younger, and I lost my sight. I was blind and went through many surgeries before I regained my sight. I know what it’s like to feel blind and not be able to see.”

I went on with the story. “When Bartimaeus heard it was Jesus of Nazareth, he cried out, ‘Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me.’ And the crowd rebuked him, and said, ‘Be quiet.’”

I asked the ladies, “So what does that tell you about the crowd? They’re telling him to be quiet. How did that make Bartimaeus feel?” And the same woman said, “Don’t ask me that question because you will make me cry. And I don’t want to ruin my makeup. Because I know.”

Because these are all prostitutes. They know what it’s like to be rejected. I continued the story: “Jesus says bring him and the crowd brings him. And when he comes to Jesus, Jesus says to him, what is it that you want me to do for you?”

And I thought, Oh, dear God. I’m going to have to ask that question. I said, “You know that Jesus is here right now with us, and he knows you. He is asking you this question. What is it that you want him to do for you?”

And this same woman said, “Can we ask anything?” I thought she’d say, new house, a car, $1,000,000. I said, “Yes.”

She said, “I want a child.”

My heart just sank. In a brothel, this woman is sleeping with who knows how many men. And she was not well preserved. The woman had seen some life. I just thought, Lord, You hear this. I said, “We will pray.” And in my doubt, in the wee hours of the morning, we left.

The team and I went to an all-night coffee shop. I asked my friend, “How in the world can we pray for a child to be born to this prostitute?”

She said, “Sharon, this could be her escape. Having a baby could be her only way out.”

All right, Lord, I thought. Then we leave this in your hands. I’m scared to ask. You said anything.

A few months later I asked the team if anyone had heard from the woman. They replied, “Oh, yes. She’s pregnant. And she has left the business, and we don’t know where she went. But she’s left.” We began to pray that wherever she was, that she would know that it was Jesus who had given her this child, and that God would give her a safe place.

By faith, we believe that God has birthed life in this woman – not just with the baby, but in Him. God’s grace rescued this woman through a physical child. And we believe that God either has, or is, bringing her to himself.

•••

Hill says she usually doesn’t get to know how people’s stories end. But that night in the brothel, a woman heard the end of the Bartimaeus story: “And Jesus said, your faith has healed you. Receive your sight. And immediately he received his sight. And He followed Jesus along the way”

“Jesus gave Bartimaeus freedom to go his own way,” Hill says. “But he chose to follow Jesus. We believe that the woman is also doing the same thing.”

Jenifer Jones is a communicator for TMS Global (tms-global.org). TMS Global is a sponsor of the Beyond the Walls mission conference to be held April 27-29 at The Woodlands Methodist Church in The Woodlands, Texas.

*Pseudonym is used for security reasons.