by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

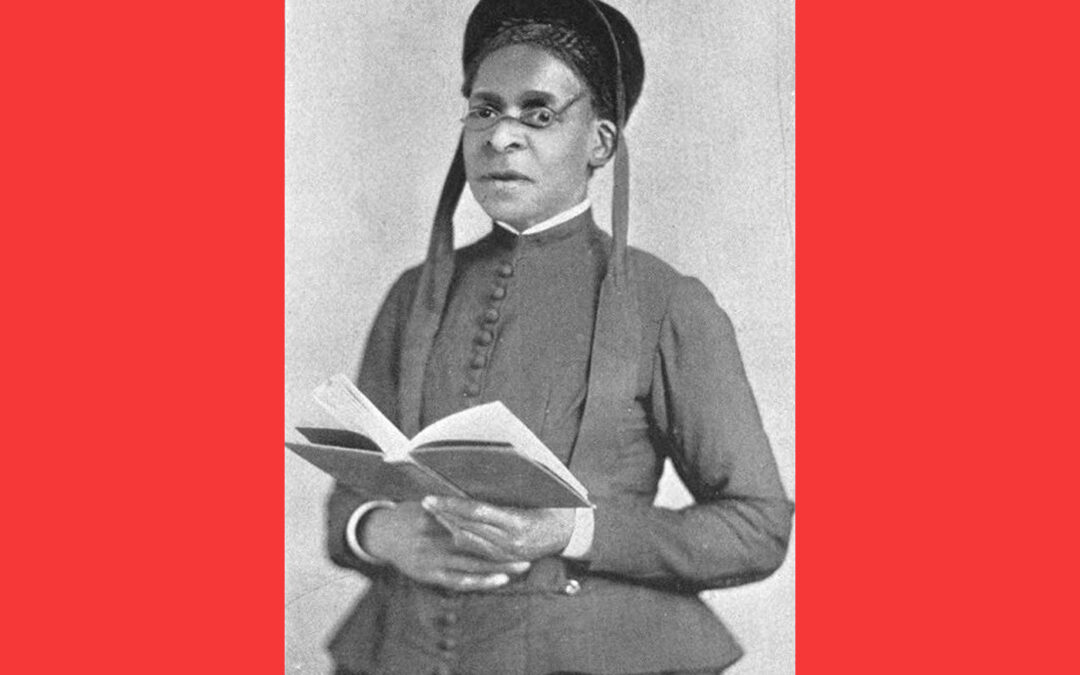

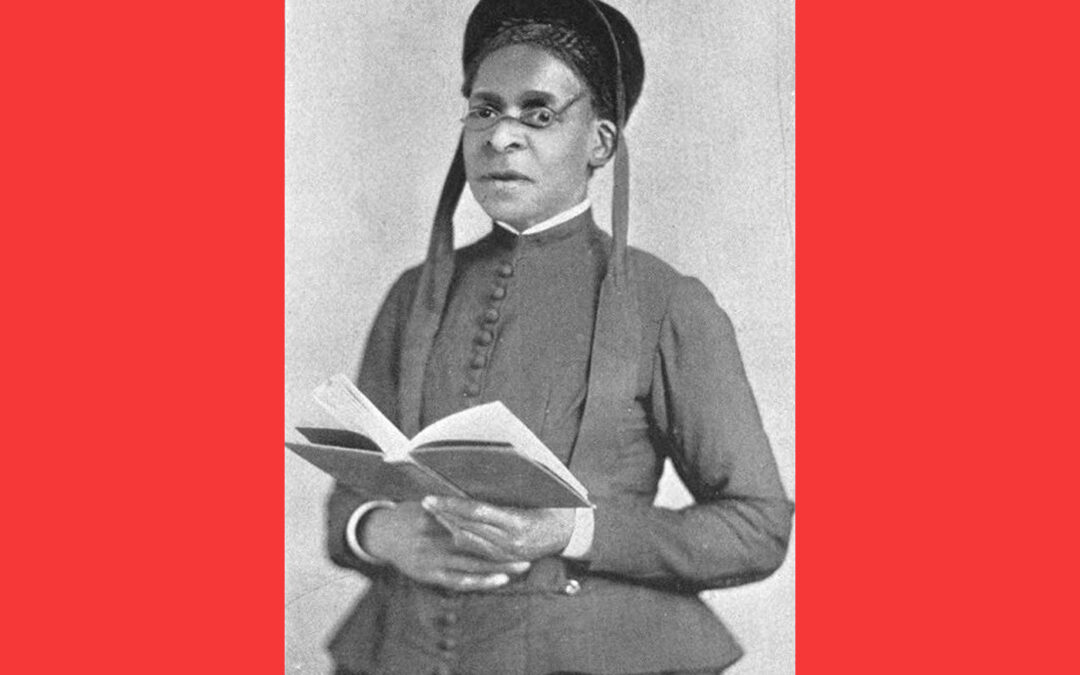

Julia Foote and the Geography of Witness

By Elizabeth Glass Turner – 2021 –

What do you know of Zanesville, Ohio? History buffs might enjoy its distinct Y-shaped bridge or explore its history as part of the Underground Railroad or recall it for its well-known river and locks. If a spiritual pilgrimage were traced across the tilts and rolls of Ohio’s farms, rivers, and valleys, Methodists might mark a gentle circle around Zanesville. It’s not unique for towns that sprang up across the Midwest to have Methodist fellowships woven through their roots; but those Methodist fellowships in the mid-1800s were not without profound flaws.

In the autobiography of Julia Foote – happily available for download through Asbury Theological Seminary’s First Fruits Press – readers are confronted with this reality. On joining the local Methodist Episcopal church (in the state of New York), her parents, both former slaves, were relegated to seating in one part of the balcony of the local church and could not partake of Holy Communion until the white church members, including the lower class ones, had gone first.

Eventually, Julia Foote would become the first woman ordained a deacon in the AME Zion church, the second woman ordained an elder. Before that, she was an evangelist, traveling and preaching in a number of places, starting before the Civil War. At times, congregational conflict emerged when she visited a town, sometimes because Foote was Black, sometimes because she was a woman. But the testimony of her visit to Zanesville is different.

Before arriving in Zanesville in the early 1850’s, Foote had been in Cincinnati and Columbus, then visited a town called Chillicothe. Her time in Chillicothe was fruitful but not without controversy.

The following excerpts retain Foote’s own original language, a reflection of the time in which she lived:

“In April, 1851, we visited Chillicothe, and had some glorious meetings there. Great crowds attended every night, and the altar was crowded with anxious inquirers. Some of the deacons of the white people’s Baptist church invited me to preach in their church, but I declined to do so, on account of the opposition of the pastor, who was very much set against women’s preaching,” she wrote. “He said so much against it, and against the members who wished me to preach, that they called a church meeting, and I heard that they finally dismissed him. The white Methodists invited me to speak for them, but did not want the colored people to attend the meeting. I would not agree to any such arrangement, and, therefore, I did not speak for them. Prejudice had closed the door of their sanctuary against the colored people of the place, virtually saying: ‘The Gospel shall not be free to all.’ Our benign Master and Saviour said: ‘Go, preach my Gospel to all’” (Julia A. J. Foote, A Brand Plucked from the Fire: An Autobiographical Sketch, First Fruits Press).

Whether or not the good Baptists of Chillicothe today know that their forebears ousted a pastor who objected to a woman evangelist, the Methodists may be unaware that their forebears invited a Black woman to preach – but only if people of color were excluded from the meeting. And yet, in spite of these local controversies, Julia Foote wrote that in that town, “we had some glorious meetings,” and “the altar was crowded.” Like John Wesley, Foote sowed grace outside church buildings, even if she could not sow grace inside church buildings. Like the Apostle Paul, she proclaimed the Gospel to those who would welcome her.

But then, she went to Zanesville. And here, readers see a different move of the Holy Spirit. What was the difference?

“We visited Zanesville, Ohio, laboring for white and colored people. The white Methodists opened their house for the admission of colored people for the first time. Hundreds were turned away at each meeting, unable to get in; and, although the house was so crowded, perfect order prevailed,” Foote wrote in A Brand Plucked. “We also held meetings on the other side of the river. God the Holy Ghost was powerfully manifest in all these meetings. I was the recipient of many mercies, and passed through various exercises. In all of them I could trace the hand of God and claim divine assistance whenever I most needed it. Whatever I needed, by faith I had. Glory! glory!! While God lives, and Jesus sits on his right hand, nothing shall be impossible unto me, if I hold fast faith with a pure conscience.”

Foote labored for any and all for the sake of the Kingdom when she arrived in Zanesville. While there, for the first time, Methodist worship was integrated. So many people came, hundreds had to be turned away. Despite the crowds, there was no controversy or dispute. And – “God the Holy Ghost was powerfully manifest in all these meetings.” There was no segregated worship; the Holy Ghost was powerfully manifest.

This is powerful testimony reverberating down through the soil, through the generations, through the Kingdom. Sitting today in a different part of the state over 150 years later, I read the words of Julia Foote and see the rolling hills of Ohio differently. I’ve been in Cincinnati, and Columbus, and Chillicothe. I’ve read those names on road signs. I’ve seen church buildings in those places. Through her words, I hear the voice of a mother of American Methodism, particularly the holiness movement, calling across the rivers, the years. She was pressed, but not crushed; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. Her eyes too saw this rural landscape in the springtime; heading from Zanesville on to Detroit, she also likely saw Mennonite and Amish farmers along the road. She sowed grace into this landscape before my great-grandmother was born. Before the Wright brothers followed the birds skimming along air currents, Julia Foote learned how to glide on the wind of the Spirit: “whatever I needed, by faith I had.”

Today, in the yard outside my window, irises are blooming that I did not plant; someone else planted, another watered, and I enjoy the deep purple unfurling from the bud. Reading of Foote’s ministry, I am given a window onto the grace planted by faith, the results of which would have shaped the spiritual life of a community for decades. But it does not let me rest on what came before; her labor calls out across the rivers, the years, questioning: how are you tending to what others planted through the Spirit? She endured great hardship to proclaim the Word of God in this landscape. I would not rip out or mow over the irises carefully planted by another; how might I help to care for what she was bold enough to sow? Decades later – and yet not so very long at all – where is the Spirit brooding, full, like a thundercloud full with rain, ready to burst?

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

The gifts you have, for the good of others.

It is the Holy Spirit who transforms history into testimony, the same Spirit who was “powerfully manifest” now bearing down, laboring again. In the original introduction to A Brand Plucked, Thomas K. Doty wrote, “Those of us who heard her preach, last year, at Lodi, where she held the almost breathless attention of five thousand people, by the eloquence of the Holy Ghost, know well where is the hiding of her power.”

What do you know of Zanesville, Ohio? That Julia Foote preached there in the 1850s, sowing grace? That Methodists there rejected segregated worship, joining together, and the Holy Spirit was “powerfully manifest”?

What do you know of the Holy Spirit, today? What do you know of those who planted and watered while God gave the increase, long before you saw the buds?

Sisters and brothers, we do not walk into ministry alone today. Wherever you are, someone has gone ahead, sowing grace ahead of you. If the rivers could speak, they might gossip to you about the ones who went before; who crossed rivers when no plane had yet crossed the sky.

What do you know of Zanesville, Holy Spirit? Hearts there once were soft.

What do you know of the Holy Spirit, Zanesville? Once, the Spirit was powerfully manifest in your midst.

Holy Spirit, where are you brooding now? Give us the grace of readiness..

Elizabeth Glass Turner, a frequent contributor to Good News, is the editor of Wesleyan Accent (www.WesleyanAccent.com). This article is reprinted by permission of Wesleyan Accent.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“The Sabbath is different from the other six days, because it is the day we stop using our time to gain something for ourselves and return to the fact that our time belongs to God,” writes the Rev. Nako Kellum. Photo by Tyler Lastovich (Pexels).

By Nako Kellum –

Shortly after I bought my first smart phone, I was at Disney World with my family for vacation. When I was standing in line for “It’s a Small World,” I received a text from work, and without thinking, I answered it immediately. Then, a thought came to me, “If I did not have this phone, I could not have been reached, and I would not have responded during my vacation!” That day, I felt like I lost something significant.

With the advance of technology, it is difficult to keep the Sabbath. Instead of going to work and sitting in front of computer, we carry “work” with us, 24/7.

I have to confess that for a long time, I have had “days off,” but I have not practiced Sabbath keeping. According to Eugene Peterson, these two are different things. He calls a day off “a bastard sabbath.” Usually, my days off are filled with different “have-to” errands – grocery shopping, cooking, doing laundry, cleaning, the children’s extra-curricular activities, etc. It was not until recently that I learned about what observing the biblical Sabbath truly means, and how much I need it.

Of course, I knew Sabbath-keeping is one of the Ten Commandments, but I do not think I took it as seriously as the other Commandments. I was careful about not having any other gods or making an idol and even preached about it. I was careful to not use the name of the LORD in vain. I honored my parents, and I took the commandments against murder, adultery, stealing, and coveting seriously. But Sabbath keeping? Not so much. Yet, in the Ten Commandments, it is the only commandment that comes with the reason as to why we have to keep it. “Remember to observe the Sabbath day by keeping it holy … For in six days, the LORD made the heavens, the earth, the sea, and everything in them; but on the seventh day he rested. That is why the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and set it apart as holy” (Exodus 20:8,11, emphasis added).

God established the rhythm of our lives in creation – work for six days and stop on the seventh day. It is based on God’s action in creation, and as his image-bearers, we are to follow him. If we play by our own rhythm instead of God’s, we disrupt the harmony God built into his creation. Maybe that is why we have problems such as stress or burn-out; we are out of sync with his rhythm.

The Sabbath is not just a simple day that we quit working; it is a day of “rest dedicated to the LORD your God” (Exodus 20:10). It is a day we reorient our perspectives on our lives. Sabbath in Hebrew means to “cease” or to “stop.” The Sabbath is different from the other six days, because it is the day we stop using our time to gain something for ourselves and return to the fact that our time belongs to God. It is the day we remind ourselves that we are not God; it is God who runs this universe. It is interesting that in Jewish culture, the Sabbath begins at sundown on Friday and ends at sundown on Saturday. All we must do at sundown is eat and go to bed; the only one who is awake is God. When we wake up, God is already at work. It reminds me that God is the one who takes the initiative, and he is the one who is sustaining the world. My part is to see what he is already doing and participate in his work. It is a day to pay close attention to God, and what he does in this world.

Another aspect of the Sabbath is that it is a day to remind us of who we are – human “beings,” not human “doings.” In Deuteronomy 5:15, after giving the commandment on the Sabbath, Moses says, “Remember that you were once slaves in Egypt, but the LORD your God brought you out with his strong hand and powerful arm. That is why the LORD your God has commanded you to rest on the Sabbath day.” The Israelites came out of slavery, during which time they were treated harshly and had to work seven days a week. They probably felt relief that they had a day that they did not have to work. When we value human beings, including ourselves, in terms of productivity, we lose a bit of our humanity, as God created us to be. He did not create us to be machines, but he created us as “beings” who enjoy being with him and with people. The Sabbath lets us just “be” in his presence and with each other, without worrying about being productive or accomplishing something. This may be one of the most counter-cultural things we can do as Christians now, in a culture where people are valued in terms of how much money they make, or their status, or which school they attended.

God blessed the seventh day of Creation, and he blesses the Sabbath day. Psalm 92 is a song of the Sabbath Day, which starts with giving thanks and praise to God. The Sabbath is a day of celebration and worship, as we give thanks and praise to God for who he is and his work. It is a day to enjoy God’s creation, delighting in the good gifts he has given us, and simply having fun.

To be honest, observing the Sabbath has not been easy. It is difficult for me to keep a full day of Sabbath (which I try to do on Saturday), but let me share a few things I have learned so far:

• Observing the Sabbath is a spiritual discipline. It does not just happen automatically. It takes intentionality just like any other spiritual discipline.

• It takes preparation. If I want to take a break from doing chores, I need to finish them by my Sabbath. It means no more procrastination regarding my work, which means I have to prioritize what I do during the six days.

• I must be careful not to be legalistic about it either. Jesus said, “The Sabbath was made to meet the needs of people, and not people to meet the requirements of the Sabbath.” I have to keep in mind the heart of God behind the Sabbath and see it as a gift and grace from God. There are days I cannot keep 24 hours of Sabbath, and that is okay for now.

• The church runs fine without me, and our family is fine even if the house is not tidy and we eat frozen pizza on paper plates. In other words, I have learned the world runs just fine without me running around, trying to do all my “have-to” errands. It takes away a sense of self-importance and control and it reminds me that God is the one who initiates the work and He’s always at work.

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

If you do not keep the Sabbath, I invite you to join me in this journey of Sabbath-keeping. Let us not check texts or emails for a day. Let us just “be” with God and with each other. Let us go outside and put ourselves in his creation that he has called “good.” Let us rest, have fun, and enjoy the good and beautiful gifts God gives us and be thankful.

Nako Kellum is co-pastor in charge at Tarpon Springs First United Methodist Church in Tarpon Springs, Florida. The Rev. Kellum is also a member of the Wesleyan Covenant Association Global Council. This article originally appeared on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website and is reprinted here by permission.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

On September 4, 1771, Francis Asbury left England in order to preach the gospel in America. During his lengthy journey, Asbury asked himself, “Whither am I going? To the New World. What to do? … I am going to live to God, and to bring others so to do.” We celebrate this 250th anniversary of his crossing the Atlantic to share the gospel of Christ. Francis Asbury statue at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. Good News file photo.

By John Wigger –

Francis Asbury lived one of the most remarkable lives in American history, a life that many have admired but few have envied. The son of an English gardener, he became one of America’s leading religious voices and the person most responsible for shaping American Methodism.

During his 45-year career in America (he died in 1816), he never married or owned much more than he could carry on horseback. He led a wanderer’s life of voluntary poverty and intense introspection.

The church and the nation ultimately disappointed him, but his faith never did. Asbury embodies Methodism’s greatest successes and its most wrenching failures.

Asbury traveled at least 130,000 miles by horse and crossed the Allegheny Mountains some sixty times. For many years he visited nearly every state once a year, and traveled more extensively across the American landscape than probably any other American of his day. He preached more than ten thousand sermons and probably ordained from two thousand to three thousand preachers. He was more widely recognized face to face than any person of his generation, including such national figures as Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Landlords and tavern keepers knew him on sight in every region, and parents named more than a thousand children after him. People called out his name as he passed by on the road.

Like any good eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century evangelical, Asbury was never satisfied with his own piety or labors. Yet people saw in him an example of single-minded dedication to the gospel that they themselves had never managed to attain, but to which, on their better days, they aspired. In their eyes he was indeed a saint. Though he spent his life traveling, he insisted on riding inexpensive horses and using cheap saddles and riding gear. He ate sparingly and usually got up at 4 or 5 a.m. to pray for an hour in the stillness before dawn. No one believed that Asbury was perfect, and even his most ardent supporters admitted that he made mistakes in running the church. Yet his piety and underlying motivations seemed genuine to almost everyone.

His legacy is not in books and sermons, but in the thousands of preachers whose careers he shaped one conversation at a time, and in the tens of thousands of ordinary believers who saw him up close and took him (in however limited a way) as their guide. Asbury communicated his vision for Methodism in four enduring ways.

1. Asbury had legendary piety and perseverance, rooted in a classically evangelical conversion experience. Piety isn’t a word we use much anymore. It simply refers to devotion to God and serving others, to a desire to “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind,” and “thy neighbour as thyself.”

Where most Methodists, even most preachers, settled for a serviceable faith, Asbury strove for a life of extraordinary devotion. During his forty-five years in America he essentially lived as a houseguest in thousands of other people’s homes across the land. He lived one of the most transparent lives imaginable, with no private life beyond the confines of his mind. Asbury’s piety brought him respect, even renown, based on sacrifice rather than accumulation of buildings, money, or other trappings of power.

2. Asbury communicated his vision through his ability to connect with ordinary people. As he crisscrossed the nation from year to year, he conversed with countless thousands, demonstrating a gift for building relationships face to face or in small groups. It is remarkable how many of those he met became permanent friends, even after a single conversation. They loved to have him in their homes. Asbury often chided himself for talking too much and too freely, especially late at night. He considered this love of close, often lighthearted, conversation a drain on his piety. In reality it was one of his greatest strengths, allowing him to build deep and lasting relationships and to feel closely the pulse of the church and the nation.

Henry Boehm, who traveled some 25,000 miles with Asbury from 1808 to 1813, recalled that “in private circles he would unbend, and relate amusing incidents and laugh most heartily.” He could also be funny, which enhanced his appeal.

3. Asbury understood and used popular culture. Asbury was remarkably well-informed (the product of his travels and love of conversation) and flexible in keeping up with these changes, but everyone has their limits. Though the American Revolution led to a good deal of persecution of American Methodists, Asbury fretted that its end would produce too much prosperity and thereby dampen Methodist zeal. As long as they were poor, most Methodists agreed with Asbury that wealth was a snare. But as Methodists became generally more prosperous, they became less concerned about the dangers of wealth, much to Asbury’s dismay.

4. Asbury communicated his message through his organization of the Methodist church. He was a brilliant administrator and a keen judge of human motivations. As Asbury crisscrossed the nation year in and year out, he attended to countless administrative details. Yet he never lost sight of the people involved. “I have always taken a pleasure as far as it was in my power, to bring men of merit & standing forward,” he wrote to the preacher Daniel Hitt in 1801.

The system Asbury crafted made it possible to keep tabs on thousands of preachers and lay workers. No merchant of the early nineteenth century could match Asbury’s nationwide network of class leaders, circuit stewards, book stewards, exhorters, local preachers, circuit riders, and presiding elders, or the movement’s system of class meetings, circuit preaching, quarterly meetings, annual conferences, and quadrennial general conferences, all churning out detailed statistical reports to be consolidated and published on a regular basis.

Under Asbury, the typical American itinerant rode a predominantly rural circuit 200 to 500 miles in circumference, typically with twenty-five to thirty preaching appointments per round. He completed the circuit every two to six weeks, with the standard being a four weeks’ circuit of 400 miles. This meant that circuit riders had to travel and preach nearly every day, with only a few days for rest each month.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

The Methodist church grew at an unprecedented rate, rising from a few hundred members in 1771, the year he came to America, to more than two hundred thousand in 1816, the year of his death. Methodism was the largest and most dynamic popular religious movement in America between the Revolution and the Civil War. In 1775, fewer than one out of every eight hundred Americans was a Methodist; by 1812, Methodists numbered one out of every thirty-six Americans.

He believed that true religion embraced the suffering of the poor and did all that was possible to alleviate it. This is why he allowed himself few comforts. He once told Boehm “that the equipment of a Methodist minister consisted of a horse, saddle and bridle, one suit of clothes, a watch, a pocket Bible, and a hymn book. Anything else would be an encumbrance.” Indeed, Asbury rarely owned much more than this. At the same time, he gave away nearly all the money that came his way.

“His charity knew no bounds but the limits of its resources; nor did I ever know him let an object of charity pass without contributing something for their relief,” John Wesley Bond wrote. He recalled that Asbury often gave money to strangers he met on the road whose circumstances seemed dire, especially widows. He had his share of failings, but the love of money wasn’t one of them.

Much of what makes human life so interesting – family, romance, creating an intellectual legacy – were largely absent from Asbury’s life after his arrival in America as a missionary. But Asbury’s life wasn’t flat, revolving as it did around the relationships he formed with other Methodists. Asbury lived his life in public, and the community of Methodist believers spread across the country became his vast extended family. He must be understood in this context or not at all. Like a rock thrown into a pond, his life sent ripples through the Methodist movement to its most distant reaches.

Asbury wasn’t an intellectual, charismatic performer, or autocrat, but his understanding of what it meant to be pious, connected, culturally aware, and effectively organized redefined religious leadership in America.

John Wigger is Professor of History at the University of Missouri. He is the author of PTL: The Rise and Fall of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Evangelical Empire, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America and co-editor, with Nathan Hatch, of Methodism and the Shaping of American Culture. Reprinted with permission from American Saint: Francis Asbury & The Methodists by John Wigger, published by Oxford University Press, Inc. © 2009 Oxford University Press.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

“I am convinced that tithing to a missional organization and then serving that organization is the most strategic thing you can do to change the world,” writes Dr. Carolyn Moore. Photo: Shutterstock.

By Carolyn Moore –

Jesus understood the deep and rich connection between our stuff and our souls. He knew that giving is not a financial issue, but a spiritual issue. We know this, because the Bible is full of this kind of talk. It contains more than 700 references to our use of money. Two-thirds of Jesus’ parables talk about materialism and money. Jesus talked more about money than he did heaven and hell and prayer combined. I’d say that Jesus thinks how you use your money matters.

That’s why I love talking about money in church. I get the connection between our faith and our stuff, and I know it can be a real barrier for some of us in growing toward Jesus. So I love talking about it as a discipleship issue and as a spiritual discipline; and I have a genuine desire to see Jesus holy-fy every nook and cranny of our life.

I am convinced that tithing to a missional organization and then serving that organization is the most strategic thing you can do to change the world, and this pandemic has only strengthened that conviction. I believe this with my whole being: As a faithful giver and also as a concerned voter, I believe my vote is not the most powerful tool at my disposal. My active connection to my local missional community is my most powerful tool against the darkness in this world. Because remember: the mission of Jesus begins in relationship. Giving is not first of all about mission or efficiency or even evangelism. Giving is rooted in relationship – being with, not doing for. This is the gist of Acts 4:32, which I believe best sums up how a life steeped in grace is lived out: “All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had” (Acts 4:32).

This is the attitude of people who have been transformed through the power of the Holy Spirit. We become the New Covenant temple (or as Tim Mackie puts it, “The temple becomes us.”). We see ourselves and our stuff not as ours at all but as part of a whole. Our character becomes that of a confident giver, because we have received the spirit of God who is at his core a Giver. God is a giver who gives to us, and when his Spirit fills us his character becomes our character. And that self-giving connects us back to God.

This Acts 4:32 life is so in rhythm with God’s ways, so in sync with his purposes, that the journey is no longer a fight against a self-protective spirit but a knee-bowing, Spirit-bearing, hungry cry for boldness to speak the Word and become an extension of God’s healing, sign-producing, and wonder-inspiring hand.

N.T. Wright puts it this way: “What you do with your money and possessions declares loudly what sort of a community you are, and the early church’s practice was clear and definite.” Their practice was Acts 4:32.

And it really does work! Ron Sider has done the math and he says, “If American Christians simply gave a tithe rather than the current one-quarter of a tithe (which is our average), there would be enough private Christian dollars to provide basic health care and education to all the poor of the earth. And we would still have an extra $60-70 billion left over for evangelism around the world.”

In the words of Acts 4:32, we discover the audacious claim of generosity: Out of giving comes great power.

Friends, grace is power. When it comes to giving, more information won’t give you more power. More time, more resources, more control, more … you name it … none of it will give you more power. When it comes to giving, grace is power.

This is exactly how it worked with the apostles.

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

Out of giving comes great power.

There is such a deep and rich connection between our stuff and our souls. That’s why money really is a significant discipleship issue. It is because Jesus has a deep desire to holy-fy every nook and cranny of your life, especially the parts you’d rather protect. And that is because Jesus wants your heart … all of it.

Carolyn Moore is the founding and lead pastor of Mosaic Church in Evans, Georgia. She is the chair of the Wesleyan Covenant Association Council. Dr. Moore is the author of many books including Supernatural: Experiencing the Power of God’s Kingdom. Dr. Moore blogs at artofholiness.com. Reprinted from her blog by permission.

by Steve | Dec 28, 2021 | Magazine Articles, November/December 2021

Delegates to the 2019 Legislative Assembly of the Wesleyan Covenant Association deliberate on proposals presented to the body. Photo courtesy of the Wesleyan Covenant Association.

By Thomas Lambrecht –

What will the proposed new Global Methodist Church look like? How will it operate? In what ways will it be different from what we have been accustomed to in The United Methodist Church?

These questions weigh on the minds of people who are thinking about the option of aligning with the GM Church after the UM Church’s 2022 General Conference adopts the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation.

Change is difficult. We tend to prefer sticking with what we are used to. Of course, the whole reason for forming the GM Church is because we believe there are some crucial changes needed in how the UM Church currently operates.

Forming a new denomination essentially from scratch is a difficult and complex undertaking. Most United Methodists have never read the Book of Discipline, and they trust their pastor, district superintendent, and bishop to know how the church is supposed to run. Therefore, comparing provisions in the UM Church’s 800-page Book of Discipline with the GM Church’s much shorter Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline would be a tedious task for most United Methodists.

That is why we have undertaken to produce a comprehensive comparison chart (it has been posted on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website as a pdf – wesleyancovenant.org). It summarizes the main provisions of the UM Book of Discipline, the Global Methodist Church’s Transitional Doctrines and Discipline, and the proposals from the Wesleyan Covenant Association’s draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline. The chart shows how most of the important provisions of church governance are handled in the UM Church compared with how they would be handled in the GM Church.

It is important to keep the three documents clear in our understanding. The Book of Discipline governs how United Methodist conferences and congregations function today. It was adopted by the 2016 General Conference (with a few revisions in 2019) and is the result of an evolutionary process extending back to the very first Discipline in 1808. We do not know what the UM Church’s Book of Discipline will look like after the realignment contemplated by the Protocol is accomplished, but we know that significant changes to the church’s moral teachings have been proposed.

The Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline will govern how the GM Church functions from its inception until its convening General Conference meets (an approximately one- to two-year period). It borrows some features from the UM Discipline and some ideas from the WCA’s draft Book of Doctrines and Discipline. It was drafted by a three-person writing team and then amended and approved by the Transitional Leadership Council, which is the governing body for the GM Church from now through the transition until the convening General Conference.

The Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline fleshes out in greater detail than the WCA draft book some of the critical elements necessary to have the denomination running. It elaborates transitional provisions that would help individuals, clergy, congregations, and conferences move into the GM Church. However, anything that was not necessary for the transitional period – such as the manner of selecting and appointing bishops – has been left for the convening General Conference to decide.

In order to minimize the amount of change that congregations would experience during the transitional period, the Transitional Leadership Council sought to maintain continuity with the current UM Discipline where it made sense – such as in the appointment process for clergy to churches (although enhanced consultation with congregations will be required). At the same time, some critically important reforms – such as shortening the timeline for candidacy to ordained ministry – were incorporated in the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline as essential elements of the new church and features that would set the direction of the denomination.

Four of the issues on the Comparison Chart regarding Methodism’s future found on the Wesleyan Covenant Association website.

Ultimately, the GM Church’s convening General Conference, composed of delegates elected globally from among those who align with the new church, will have the authority to formally adopt a new, more permanent Book of Doctrines and Discipline. It will undoubtedly build as a starting point upon the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline. The WCA’s recommendations and other ideas laity and clergy wish to propose will be considered and potentially adopted by the General Conference. Notably, WCA recommendations not in the transitional book would not take effect unless adopted by the convening General Conference. However, they are an important indicator of the current thinking of denominational leaders.

The comparison chart is meant to be an easy way to compare how the GM Church will function during the transition and give an indication of some of the directions envisioned for its future. The chart may be reproduced and shared freely. Questions and feedback are welcome and can be sent to info @ globalmethodist.org.

Some highlights from the chart, specifically referring to the GM Church’s transitional period:

• Doctrine – The doctrinal standards will stay the same, with the addition of the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds, and bishops and clergy will be expected to promote and defend the doctrines of the church.

• Social Issues – The Transitional church will be governed by a two-page statement of basic social witness in the Transitional Book of Doctrines and Discipline, compared with over 930 pages in the UM Discipline and Book of Resolutions. That statement would be binding on clergy and congregations. No changes or additions to this statement will take place before the inaugural General Conference of the new denomination. That General Conference will determine whether and how to write an expanded statement of social principles.

• Local Church Membership Categories – Similar to the UM Church.

• Local Church Organizational Structure – Flexible structures allowed to accomplish the necessary administrative tasks.

• Connectional Funding (Apportionments) – 1.5 percent of local church income for general church work, 5-10 percent for annual conference, including the bishop’s salary and expenses.

• Trust Clause – Local church owns its property (no trust clause). Local churches with pension liability would remain liable if the church disaffiliates.

• Local Church Disaffiliation – Would allow for involuntary disaffiliation if necessary for churches teaching doctrines or engaging in practices contrary to the GM Book of Doctrines and Discipline. Voluntary disaffiliation possible by majority vote of the congregation. No payments required, except pension liabilities where applicable, secured by a lien on the property.

• Certified Laity in Ministry – Combines all types into one category called certified lay ministers, who can specialize to serve in any of the previous areas (e.g., lay speakers, lay servants, deaconesses, etc.).

• Orders of Ministry – Order of deacon contains both permanent deacons and those going on to elder’s orders.

• Length of Candidacy for Ordained Ministry – Six months to three years.

• Educational Requirements for Deacons – Five or six prescribed courses before ordination and four or five courses thereafter.

• Educational Requirements for Elders – Six prescribed courses before ordination and four courses thereafter.

• Licensed Local Pastors (non-ordained) – Grandfathered in, but transitioned to ordained Deacon or Elder.

• Funding for Theological Education – Theological Education Fund to make loans to students that are forgivable (20 percent for each year of service to the church).

• Retirement for Bishops and Clergy – No mandatory retirement, clergy may choose senior status. Senior clergy not under appointment are annual conference members with voice and vote for seven years. Thereafter, members with voice only.

• Election and Assignment of Bishops – Election process to be determined. Term limits envisioned, perhaps twelve years. Current UM bishops who join the GM Church will continue to serve. Annual conferences without a bishop would have a president pro tempore assigned for the transitional period.

• Appointment Process – Same as UM Church, with enhanced consultation with clergy and local church. Bishops must give a written rationale for appointing a pastor against the wishes of the congregation. Current appointments maintained where possible during transition.

• Guaranteed Appointment – No guaranteed appointment. Bishop must give written rationale for not appointing a clergyperson.

• General Church Governance – Transitional Leadership Council serves as the governing body until the convening General Conference with globally elected delegates.

• General Church Agencies – None mandated. Five transitional commissions suggested (compared with 15 UM agencies).

• Jurisdictions or Central Conferences – Optional, may or may not be formed in a particular area.

• Adaptability of the Discipline – Provisions of the Book of Doctrines and Discipline would apply equally to all geographic areas of the church unless specified. This implies provisions will be more general and consider the global context before being adopted.

• Annual Conference Agencies – Six agencies required, with additional ones at the discretion of the annual conference (compared with 25+ in the UM Church).

• Clergy Accountability – Similar to the UM Church complaint process, with stricter timelines and less discretion in dismissing complaints. Laity would be voting members of committee on investigation.

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

Many more details, as well as the WCA’s proposals following the transitional period, can be found in the chart found at wesleyancovenant.org.

My wife is a marriage and family therapist. One of her favorite questions to provoke dialog is, “How are things changing and how are they remaining the same?” That question is a fitting one to ask, as we head into a key few years of decision-making ahead. Hopefully, this chart can help provide some of the answers.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News.

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

Sister Julia issued this challenge: “Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifts you have for the good of others,” she wrote in A Brand Plucked. “How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, ‘We suffer not a woman to teach,’ thus quoting Paul’s words, but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast?”

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

• God accepts me for who I am, not for what I do. He enjoys being with me and invites me to enjoy just being with Him. He is slowly teaching me not to put my self-worth on how much I have accomplished or how many boxes I checked on my check list.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

There was another component of Asbury’s system that went to the heart of what it meant to be a Methodist, to practice a method: the necessity of a culture of discipline. As individuals and communities, believers had to take it upon themselves to regulate their spiritual lives, to maintain their own spiritual focus. He insisted on upholding the requirement that all members attend class meetings and that love feasts be limited to active members, creating an atmosphere of mutual trust and support. Though there were plenty of disagreements along the way, Methodists succeeded where other religious groups failed largely because they were more disciplined.

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

“With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need” (Acts 4:33-35).

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.

• Bishops’ Accountability – Accountable to Transitional Leadership Committee, global committee on investigation, and global trial court if needed. Laity would be voting members of the committee on investigation.