by Steve | Jan 7, 2022 | January/February 2022, Magazine Articles

Just a glimpse of the beauty found at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina. Photo by Steve Beard.

By Tara Beth Leach –

Somewhere in the mid-1990s, when I was a new Christian, I came across a popular bronze statue by Dean Kermit Allison. The sculpture was called “Born Again,” and it depicted a man shedding his old self with a bronze layer of skin, and his new self was being born anew as a radiant, glassy, crystal version. I remember staring at that statue mesmerized and in tears. I was the statue, I thought. Newly in love with Jesus and recently beginning my life in Christ, God was doing a radiant new thing in my life. But today, that statue seems more prophetic, and it tugs at my heartstrings as I long for the church of the future.

I pray that the church would begin to see, acknowledge, and name the bronze layers that are saturated with worldly beliefs and behaviors and flee from them. I pray that the church would know that we have not been destroyed – it’s not too late. I pray that we would reclaim, be renewed and revived, and allow the work of the Spirit to birth something new and radiant. Like the bronze statue, may the layers of our own systems that have hurt and harmed others begin to peel away, and may the lamp of truth, love, and righteousness be placed firmly on its pedestal and shine in all of its illuminating beauty. Not beauty for the glory of ourselves but for the glory and majesty of our King and Creator. May we shine in such a way that instead of hard lines in the sand being drawn, those who once felt excluded are now drawn to the radiant light of the church.

But birthing isn’t easy work. It’s painful, it’s laborious, it’s long, and it literally brings blood, sweat, and tears. On the early morning of April 17, 2010, I woke up at 6 a.m. to discover that my water had broken. Fortunately, I wasn’t feeling any pain yet, so I decided I could take a shower, put on makeup, and grab breakfast on the way to the hospital. By the time my husband and I arrived at Panera to pick up some breakfast on the way, the labor pains began to kick in. I’ll also confess that I had no idea that when the water breaks, it isn’t just a one-time occurrence; rather, it keeps on coming. This was rather problematic standing in line for my bagel. After a minute or two of waiting in line, I turned to Jeff with my lips curled and my teeth together and said, “We have to go now!”

By the time we got to the hospital, I was in full-blown labor. Before having Caleb, I thought of myself as a tough woman with high pain tolerance. Turns out, labor was much more painful and difficult than any friend or textbook or Lamaze class could have prepared me for.

At one point during labor, my husband and parents were in the hospital room having a good old time, sharing, eating, laughing, and watching Ghostbusters on TV. I was angry that I was suffering and they were enjoying the moment. My husband came over to me with an angelic and peaceful look on his face, gently put his hand on my shoulder, and said, “Hey, babe, I was thinking that the next baby …” Before he could even finish his sentence, I angrily interrupted him with what probably seemed like demon eyes and the voice of his worst nightmares, “Next baby? Next baby? You think I’m going to go through this again? There will be no next baby!”

Perhaps the scariest and most challenging moment came during what many call transitional labor, which is the stage between active labor – labor pains that are a few minutes apart – and actually having to push for delivery. It’s intense, and the only way for any sort of relief is to push and potentially scream. I did both. The nurses and my family surrounded me saying things like, “Breathe. Keep your eye on the prize! Caleb is coming! Breathe. Keep your eye on the prize! Focus! Caleb is coming!”

Breathe. Keep your eye on the prize. Breathe. Breathe. Breathe. Dear church, creation is groaning. The labor pains can no longer be ignored. It’s time to push and birth something new, something radiant, something wrapped in love, truth, and grace.

There is nothing glorious about labor; there is nothing easy about pushing. It hurts. It’s hard. But push we must. That is, we must repent, we must name, we must rid ourselves of toxic systems, and we must abandon the imagination of the principalities and powers of this world. Let us push, breathe, keep our eyes on Jesus, press in, lean in, and reclaim the radiant vision that comes alive in Scripture.

A Call to Radiance. In Matthew 5, Jesus steps on a mount and begins to teach. His prophetic words are drenched in love and wrapped in vision. It was a sermon unlike any other that has now found its home in what we call the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7). In it, Jesus shares his dreams for the already-but-not-yet people of God in Christ. He paints a vivid vision of how the people of God are to live, love, act, and care for one another. His words are no doubt piercing, and they likely make us squirm at times, but what Jesus proclaims is an illuminating and radiant vision for the bride of Christ.

Jesus’ words are no mere suggestion; rather, they are passionate and piercing commands for the people of God to live into no matter where they live. That is, those who are citizens of the kingdom of God.

Following Jesus’ declaration of those who make the list of the blessed life, Jesus calls the church to lean into the radiant vision of the church. He calls us salt and light.

“You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot. You are the light of the world. A town built on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead, they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:13-16).

Like other popular passages of Scripture, we sometimes miss out on the fullness of what Jesus is calling us to. Often we read this passage through the lens of I instead of we and then interpret it as, “I should do more good deeds.” However, this prophetic declaration of Jesus should push and pull the church into the radiant church it was meant to be. While one star is certainly something to behold, a sky full of sparkling stars is stunning. Our witness is corporate, found within congregations and communities. Our witness is a collective presence and voice and light rather than individuals.

This passage isn’t a random call to do good things; rather, we are called to lean into the missional imagination of the triune God – that is, the imagination that unfolds beginning in the book of Genesis.

In the first eleven chapters of Genesis, the problem of sin, brokenness, darkness, and evil is rather glaring. Murder, betrayal, division, pride, and havoc, even from Mother Nature, are just a few examples. However, we don’t observe a planless God scrambling to heal God’s broken creation, and neither do we observe God lashing out in anger. Instead, we discover a redemptive God who moves in with acts of love and grace.

Jesus is the Brightest Star. Somewhere on the margins of Bethlehem, a child is born. A bright star attracted magi from the East who wanted to see the astonishing light for themselves. Right in the middle of chaos, decay, darkness, and oppression, this child moves into the neighborhood filled with chaos and he shines. The new Israel, the second Adam, fully divine and fully human, prophet and priest, and the fulfillment of all of Israel’s history, reveals the very heartbeat and character of God. And we discover just how serious God is about keeping this covenant.

This King, after living a perfect life of love, healing, revelation, and wonders, meets his death on a cross. And there on the cross, the end of an evil era collides with the nails, the crown of thorns, and the body broken. And every spring the church gathers together to proclaim the good news, “He’s not dead! He’s alive!” We join the chorus of angels and the sermon of Mary at the tomb, “He’s alive!” The King is raised to new life, and the floodgates burst forth. We discover the promises to Abram are now fulfilled, and we are the stars in the sky. No longer is ethnic Israel the only recipient of God’s blessing; the dividing wall has been destroyed, and Jews and Gentiles, men and women, and slaves and free persons are all one in Christ. The re-creation of a people of God is expanded to all who are in Christ. The apostle Paul says, “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come: The old has gone, the new is here!” (2 Corinthians 5:17). And the apostle Peter says, “You are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s special possession, that you may declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his wonderful light. Once you were not a people, but now you are the people of God; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy” (1 Peter 2:9-10).

We are Called to Shine. Paul says to the Philippians, “Do everything without grumbling or arguing, so that you may become blameless and pure, ‘children of God without fault in a warped and crooked generation.’ Then you will shine among them like stars in the sky” (Philippians 2:14-15). We are the stars in the sky – shining in all of our radiant glory as the love of God bursts forth. We – all who are in Christ – are the royal priesthood and God’s special possession. And the news only gets better! In Christ, we begin to reflect God’s glorious image as Paul says, “And we all, who with unveiled faces contemplate the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his image with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit”(2 Corinthians 3:18).

We are heirs of God’s promises to Abraham, and we are included in God’s blessed people. And just as God called Abraham to faithfulness and obedience, God also called the church. As children of Abraham and sons and daughters of the King, we’ve distorted the story of the perfect gospel to be a ticket to heaven – or else.

We are heirs of God’s promises to Abraham, and we are included in God’s blessed people. And just as God called Abraham to faithfulness and obedience, God also called the church. As children of Abraham and sons and daughters of the King, we’ve distorted the story of the perfect gospel to be a ticket to heaven – or else.

But the radiant gospel is about a people leaning into and reflecting the goodness of God to an embattled world. The radiant gospel is about the people of God in Christ extending the table and gathering as an alternative community in a world gone awry. We are to embody the power of blessing – that in the middle of a chaotic, prideful, sinful, decaying, embattled, broken world, we would embody the promises of Abraham and live the vision of Jesus as salt and light. As a covenant community in Christ, we don’t just randomly do salt-and-light kind of things; rather, we are salt and light. As salt and light, we are called to mediate the goodness, light, love, and holiness of God. What a radiant call God has entrusted to God’s people.

Tara Beth Leach is a pastor at Christ Church of Oak Brook in the western suburbs of Chicago. She previously served as senior pastor of First Church of the Nazarene of Pasadena (“PazNaz”) in Southern California. Adapted from Radiant Church by Tara Beth Leach. Copyright (c) 2021 by Tara Beth Leach. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, PO Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60559. www.ivpress.

by Steve | Jan 7, 2022 | January/February 2022, Magazine Articles

By Steve Beard

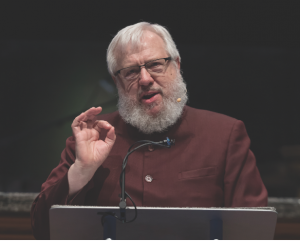

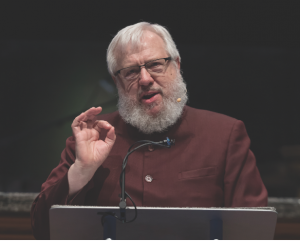

On Thursday, October 7, 2021, United Methodism lost a remarkable scholar who exercised his theological and spiritual gifts with wit and precision. Dr. William J. Abraham was one of the theologian pillars of the church – not just in Methodism, but in broader ecumenical circles, as well. He was a herculean force for traditional Wesleyan theology from his outpost at Perkins School of Theology in Dallas. Abraham’s death was unexpected. He was 73.

Like so many others within United Methodism, we were stunned and saddened by the news of the passing of the man we simply called Billy. Those of us at Good News have considered him a friend and co-laborer in the work of renewal within our denomination – even during those times when we had a hard time fully interpreting his distinct and endearing Irish accent.

Twenty-five years ago, Billy’s address at the Confessing Movement gathering in Atlanta was the featured cover story for Good News. He had just published a book entitled Waking from Doctrinal Amnesia: The Healing of Doctrine in The United Methodist Church. “We have simply forgotten our doctrinal heritage and hence have ignored its rich treasures and reserves,” he told the assembly in Atlanta.

For the magazine, we picked up on the other image he discussed. Our cover title was “Healing our Doctrinal Dyslexia.” Abraham believed United Methodism’s theological crisis was that the children of Wesley – decades later – were looking at the same material (our theological heritage) and seeing and proclaiming divergent messages. (In his honor, we have republished the essay on the pages that follow.)

“As anyone suffering from dyslexia knows, the crucial problem is that one sees the relevant marks on the page but the marks are ingested in a distorted fashion,” he said. “In the case of doctrinal dyslexia, what happens is analogous to this condition. In our case what has happened is that we have turned inside out and upside down the crucial material on doctrine in the Book of Discipline. We have displaced the actual standards of doctrine laid out in the Constitution by concentrating on the highly speculative material laid out in the section on our theological task.”

After his conversion in his teen years through the ministry of the Methodist Church in Ireland, Billy began his theological training. “In the early stages of my own intellectual and spiritual journey, Wesley was pivotal for me,” he writes in his fascinating book, Wesley for Armchair Theologians. Mysteriously, once he began his theological training, “Wesley suddenly went dead on me. I found him not so much archaic as surreal.”

Ironically, Billy’s interest in Wesleyan theology pivoted while he was on a sickbed: “Happily, listening to some purloined audiotapes on Wesley by Albert Outler during a bad dose of the flu arrested this journey away from Wesley.” He found himself a great proponent of the core message. “Wesley’s theology is an intellectual oasis lodged within the traditional faith of the church enshrined in the creeds,” he wrote.

Abraham would go on to become the Albert C. Outler Professor of Wesley Studies at Perkins School of Theology. He would often speak warmly about his appreciation for Dr. Outler, his scholarship, and his love for both Christ and the Church. Nevertheless, Abraham unflinchingly critiqued Outler’s proposed “quadrilateral.” It gives too much leeway to mistakenly believe that Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience are of equal value in interpreting divine revelation.

“The consequence is that our identity is now shaped by an interesting but dubious exercise in religious theory of knowledge. On pain of denying our tradition, we are forced to confess adherence to a piece of clever epistemology [how do we know] which was worked out in the 1960s and which is at odds both with Wesley and with the clear content of the constitutional standards of doctrine,” he believed. “In these circumstances the great classical doctrines of the faith, to which Wesley wholeheartedly adhered, are treated as optional alternatives to be received, rejected, remade, or reimagined at will. We have idolized a piece of philosophical speculation and are now reaping the consequences. Not surprisingly, we find ourselves torn asunder by conflicting doctrinal proposals.”

Professor Abraham continued: “As a pedagogical device, the quadrilateral indeed has merit. Anyone who is a teacher can testify to this. However, as a formal proposal in the field of religious knowledge, the quadrilateral is an absurd undertaking, for only an omniscient agent could seriously undertake to run our proposals through the gamut of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. Only God could use the quadrilateral and, thankfully, God does not need it.” Vintage Billy.

His message twenty-five years ago still resonates. “The quadrilateral is much like a kaleidoscope. Each time you shake Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience, a different configuration emerges,” he said back then. “The result is doctrinal chaos and incoherence. Even Albert Outler, the great architect of the Methodist quadrilateral, was disturbed by its misuse, and late in life expressed reservations about its logic.”

In the forward to The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism by Dr. James V. Heidinger II, Billy voices his curiosity about Outler’s perspective from the vantage point of eternity. “It would be great to sit in on a seminar with Outler and Wesley and other great heroes and heroines of our tradition,” he wrote. “The workers die but the work goes on, as Wesley once noted. There are eighty-two million descendants of John Wesley across the globe so Methodism is not going to disappear any day soon. The big question is what place United Methodism will have in that future.”

Looking forward. Billy Abraham was not an early proponent of dividing United Methodism. His mind, however, did change. He would come to believe that it was the most logical and peaceful option available. Speaking in front of renewal leaders back in 2014, his message is worth recalling today.

“If we are driven to separation then we should lift our heads high and not be drawn into a parochial reaction against the current networks who would take us into moral and theological heresy if not apostasy. We should be as wise as serpents and innocent as doves,” he told the Methodist Crossroads gathering. “Beyond the current crisis, we should imagine a whole new reiteration of our Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren identity and heritage. I envisage the creation of a new form of global Methodism. Let’s call it the Global Methodist Church. This would gather up the majority who have stood firm across the years and across the world and then reach out to other Methodist and Wesleyan bodies as time and energy permit.”

Abraham continued: “We need be in no hurry but we should be urgent in seeking the guidance of the Spirit to become over the next several generations an industrial-strength version of Methodism that would stretch across the world. We would also look to a whole new ecumenical future with former and newer partners willing to reach out afresh in mission and witness.”

In conclusion, Billy said, “To achieve this we will need great patience with one another. Even where we stand totally together the chemistry can be difficult to endure. This task is much too big for any one person or any one group. We must resolutely stand together and work to continue the life of United Methodism beyond its current incarnation. We can and should have a vision of a global Methodism that is substantial, bold, generous, and irrepressible.”

Writing in A Firm Foundation in 2017, Billy issued a rousing challenge for those looking to experience a fresh chapter of Wesleyanism. “We know that we have come to a crossroads in United Methodism, and we have rightly taken our stand on the moral faith of the Scriptures and of the Church through the ages,” he wrote. “It is time to move on and work for a fully faithful commitment to Christ and to find fresh expressions for the tradition we inhabit. We leave to Providence those who disagree with us.”

As a churchman, he knew the path ahead was going to be filled with challenges. “We need a combination of firmness and flexibility; of impatience and patience; of fear and confidence; and of divine wisdom and human ingenuity. Above all we need to get our act together in mission and evangelism. … The road ahead will at times be extremely difficult and even treacherous; the destination, however, will open up a new day for a fresh expression of classical Methodism and of the Evangelical United Brethren tradition.”

Within the legacy of his ministry is his wholehearted devotion to sharing his work with believers outside the United States. He knew that the historical Wesleyan message travels well beyond North American borders. “What we need is a whole new configuration of United Methodism that will be missionary-oriented, open to the full working of the Holy Spirit, unapologetically orthodox, sacramentally robust, and committed to justice and the care of the needy,” he wrote in A Firm Foundation. “In the short term, we may be a minority in the United States; worldwide, we are likely to be a global majority.”

There have been many kind remembrances of Billy since his passing. They are all touching and well deserved. To his family we pass along our heartfelt condolences. We are grateful for his intellectual and spiritual witness. His passing has left us in mourning, but his life was lived with a vigor that his legacy will be remembered with great celebration. We honor Billy’s memory by serving the Christ he proclaimed and living out the Gospel revealed in the Scriptures Billy loved.

Upon his announced retirement from Perkins School of Theology, he also announced that he would be launching the Wesley House at Truett Seminary at Baylor University in Waco, Texas (see page 22). We asked his long-time friend and colleague Dr. David Watson of United Theological Seminary to interview Billy for Good News readers in 2020. We leave you with Billy’s response to a question about parting advice.

“Be anchored in a discipline that requires rigorous standards of excellence; for me that has been analytic philosophy. Stand by the truth and work on it until it becomes essential to your identity,” Billy responded. “Never, ever be up for sale, as far as the revelation of God mediated in Scripture is concerned. Stay grounded in regular ministry in the church. Take the politics of institutions seriously; be street-smart. Know your critics better than they know themselves. Fast and pray as best you can!”

We will miss him. In his memory, we recall the passage from the Book of Revelation: “Then I heard a voice from heaven say, ‘Write this: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.’ ‘Yes,’ says the Spirit, ‘they will rest from their labor, for their deeds will follow them’” (14:30).

–Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. Photo courtesy of Southern Methodist University/H. Jackson.

by Steve | Jan 7, 2022 | January/February 2022, Magazine Articles

Photo: Shutterstock

By Joe Henderson –

Melissa Stevens, inmate number G30701 to the Florida Department of Corrections, didn’t know anything about the Rev. Kris Schonewolf the first time they met. Until that point, it had been just another day at Lowell Correctional Institution in Ocala, Florida. Stevens was nearing the end of her sentence for grand theft auto by then. She was also turning to God to deal with the inner demons that had spent a lifetime trying to ruin her.

“In prison is where I really found God,” she said. “That’s when I began praying to him.”

She grew up Catholic on the south side of Chicago but admitted, “It was more for show. There was no substance to it all, and it was just something we did every Sunday. I had no concept who Jesus is.”

But when you ask Jesus into your life, as Stevens said she did in 1999, he takes you seriously. You can run from him, but as the line in the contemporary worship song “Reckless Love” by Cory Asbury proclaims, “He chases me down, fights ‘til I’m found …”

Jesus found her in Lowell, and Stevens prayed for someone who could nurture her new-found faith through prayer, the Bible, groups discussions, and so on. That’s when Schonewolf walked by, and Stevens recalled distinctly what happened next.

“A voice inside me said, literally, ‘That’s her,’” Stevens said. “Kris had a light in her; I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Schonewolf was at Lowell to run the Oasis, a prison outreach ministry of the Florida Conference of the United Methodist Church. The program began in 2019 with the support of North Central District Superintendent Rev. June P. Edwards and Bishop Ken Carter. It is designed to shine the light of God into the darkness of incarceration.

“There were some unexpected roadblocks in the beginning — both with the Department of Corrections and then COVID-19. Yet, again, Kris never gave up,” the Rev. Edwards said.

“Now, she has the confidence of the staff and has developed both name recognition and acceptance among the women. Even though there are difficulties faced every day and unexpected changes in schedule, the women come for all of the offerings provided — worship, Bible studies, guitar lessons, crochet lessons, and the mentoring through the volunteers that write letters. Their lives are impacted in so many ways.”

Schonewolf said her approach is simple. “I just love them with the love of God,” she said. “They’re wounded, hurt, abandoned, and abused. But they are God’s daughters and deserve to be treated with respect.”

An abusive upbringing. Melissa Stevens’ life had been a nightmare until that point. Growing up, she had family members connected with the Chicago Mafia.

“It was nothing for me to walk outside with my mother and see feds taking pictures of us,” she said. She was molested and assaulted starting at age 6. By 14, she joined the Latin Kings gang and a year later had her first child.

“I had one failed marriage, and then another failed marriage. There were a lot of issues, adultery, assaults,” she said.

She went to jail in Illinois for selling drugs, and then it got worse. “I had nothing,” she said.

Not true. She had Jesus, even if she didn’t understand it at the time.

Jesus kept chasing her down.

She was in jail in Florida’s Bay County on another charge when Category 5 Hurricane Michael struck in 2018. The damage was incredible. Her prison had no running water for about a week, and inmates walked through raw sewage inside the building.

Melissa Stevens

Stevens developed an infection in atrocious conditions and wound up in a coma. Doctors didn’t believe she would survive. But while in the coma, Stevens said Jesus gave her a vision.

“He took me to the middle of the earth to show me the abyss. Walked through a giant corridor, too high to see,” she said. “There was water on both sides. Shapes on both sides, but he protected me.

“Suddenly, I snapped back into my body. Doctors said there was no sign that I was going to come back.” But she did, and her life was about to take a turn from which there is no turning back.

God has huge plans for this girl. The Oasis is literally that, a place of refuge in despair of prison life. It’s a place where the inmates find worth in lives that once might have seemed worthless.

There are seven activities a week, each one about two hours long. They have movie nights three times a month, always with an upbeat theme.

There are seven activities a week, each one about two hours long. They have movie nights three times a month, always with an upbeat theme.

“The women know I’m there for good,” the Rev. Schonewolf said. About 120 women weekly take advantage of the offerings.

“Kris would come in, and those girls would just light up. She had music and spiritual counseling,” Stevens said. “The way she talked about God, you had to listen.”

Stevens was already saved when Rev. Schonewolf met her, but that was just the start of the journey. Kris showed her what it means to be the hands and feet of Jesus. “I was able to work with her, mentor her, go one-on-one with her,” Schonewolf said.

The Rev. Edwards noticed that drive to take Christ’s love to those darkened places filled with damaged people. It’s what made Kris perfect for this task. “From the moment the possibility of this ministry was shared, Kris felt a strong sense that God was calling her to this work,” she said.

“Her spiritual gifts of prayer and healing and outreach, as well as her skills of administration and organization, lend themselves to this unique work. Early on, Kris shared this sense of call with me and never gave up.”

A lot of people gave up on Melissa Stevens. For years, maybe she even gave up on herself, but Jesus never did, and so he sent his servant, the Rev. Kris Schonewolf, to show her just that.

“I’ve prayed her through so much deliverance, spent dozens of hours with her, talked to and prayed with some of her children, watched God completely transform her, watched her struggle, prayed some more, wiped her tears, watched her lay hands on people for healing and deliverance,” she said.

“I watched her being delivered of demonic forces, been there when she had powerful visions from God, seen her preach powerfully. I’ve never believed in anyone’s story more. Yes, God has huge plans for this girl. I can see us doing ministry together when God arranges it.”

Now, look at the change in someone society might have cast away.

“Oasis did so much for me on so many levels. If it hadn’t been for that ministry, I couldn’t honestly tell you where I would be right now,” Stevens said.

“People ask me what my purpose is, and I have no idea at this point. It’s like when you’re packing your bags, and someone says, ‘Where are you going?’ When will you be back? I don’t know.”

The Rev. Kris Schonewolf

She is out of prison now, working full-time, trying to reunite with her nine children, and living a life of dedication to Jesus.

“I do communion every day. I get to witness to people on my job. I was praying for God to send people to me so I could talk about him. A guy came up and started talking to me about God, and it was like, all right,” she said.

“Whatever God’s purpose is for me, what his assignment is for me, he is revealing one little bit at a time. One thing I do know is that I will never stop talking about him until I draw my last breath. At the end of all of this, it’s all about God.”

Joe Henderson is News Content Editor for the Florida Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church (flumc.org). Reprinted by permission. Find out more about this ministry at www.TheOasisLCI.org. You can also contact Rev. Schonewolf at PastorKrisLCI@comcast.net.

by Steve | Jan 7, 2022 | January/February 2022, Magazine Articles

Life Vests and Torpedoes

By Steve Beard –

Some of the most emotional moments broadcast on television are when deployed military parents return unexpectedly to surprise their kids coming home from school, during a musical recital, or at a graduation. Sheer joy boils over and you can almost feel the tight squeeze of the bear hugs. Tears of happiness cascade down the faces of the unexpected with unreserved elation. In a perfect world, those moments would last forever.

A few years ago, I joined my family at the Mt. Soledad Veterans Memorial in San Diego to honor my grandfather, Harold L. DuVal, a veteran of World War II. For the families gathered at the site near the Pacific Ocean, it is a breathtaking experience. Those leaving flowers or touching plaques want to make sure that their loved ones are not forgotten. Walking the grounds gives a good opportunity to reflect on the service and sacrifice of men and women in uniform.

While Memorial Day in May is specially designated to remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice during military service, Veterans Day in November is an opportunity to show gratitude for all current and former members of the Armed Forces.

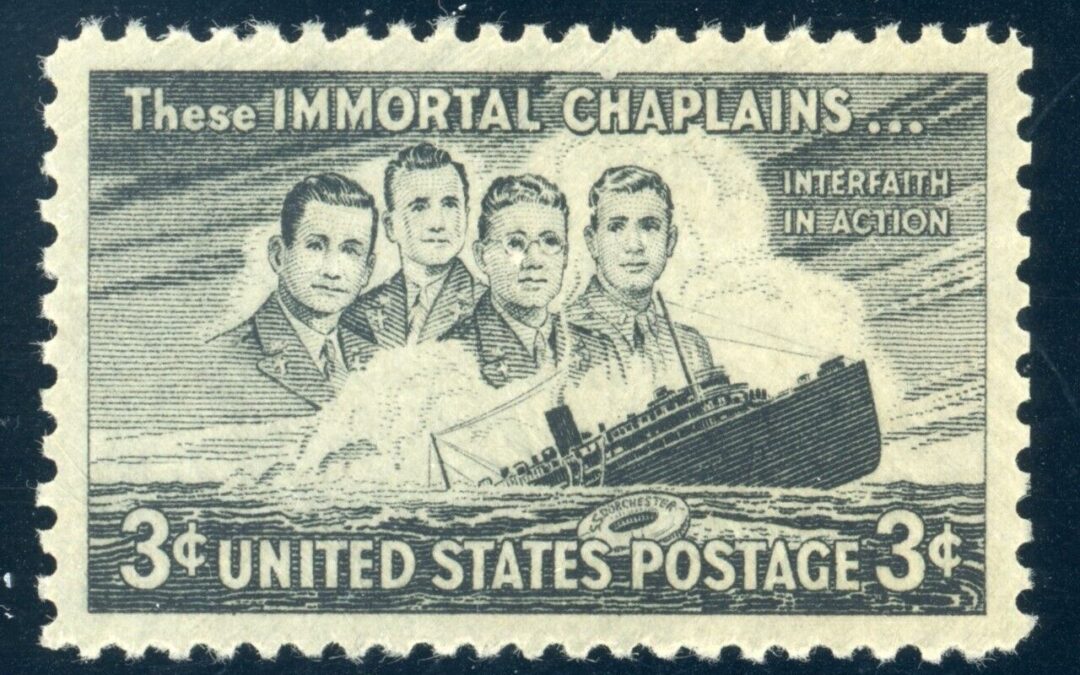

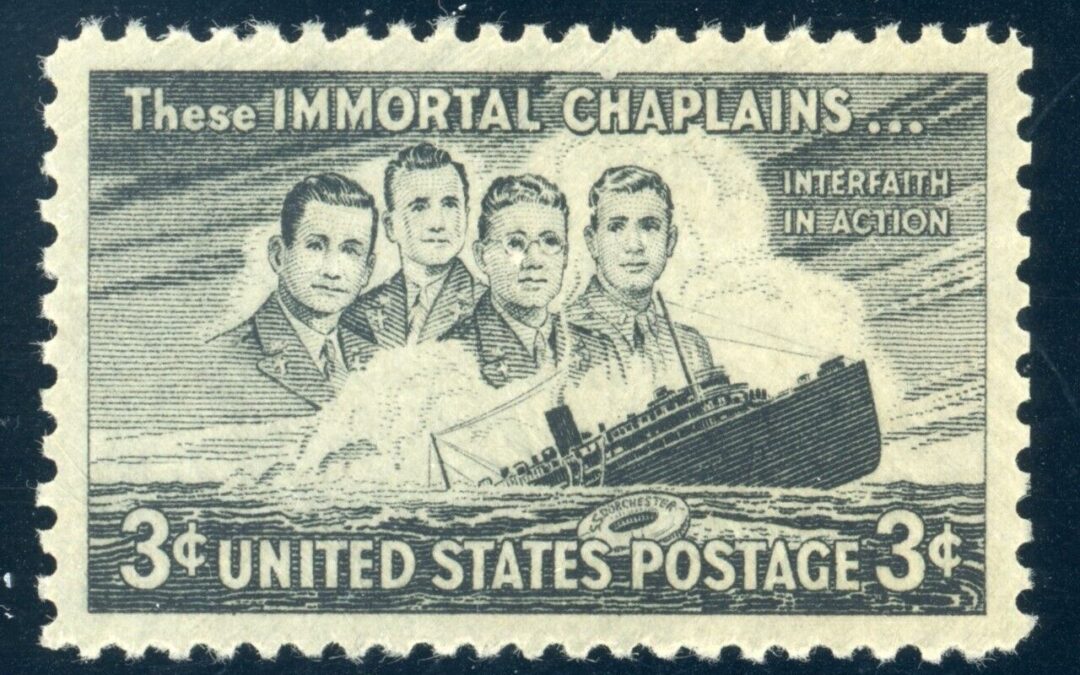

February 3 is designated as a special day to honor four specific heroes from World War II (1939-1945) and recognize their acts of self-sacrifice during a fateful night off the coast of Greenland in an area the Navy dubbed as Torpedo Alley – a treacherous stretch of the North Atlantic filled with Nazi submarines. The U.S. Army transport ship U.S.A.T. Dorchester was a cruise ship that had been repurposed to serve during wartime. It carried more than 900 military personnel, merchant marines, and civilians.

At one o’clock in the morning on February 3, 1943, a German torpedo tore a massive hole in the ship. The ship went completely dark. Sleeping soldiers woke up in a whirl of disorientation. Survivor Michael Warish described the scene in No Greater Glory: “The lights went out, and steam pipes broke, and there was screaming. Then the bunks, three to five decks high, went down like a deck of cards. Shortly after, there was a very strong odor of gunpowder and of ammonia from the refrigeration system.”

Those who were awake scrambled to upper levels to reach a lifeboat. In Bloodstained Sea, survivor Walter A. Boeckholt remembered, “I was thrown against the ceiling and then landed on the floor. By the time I was recovering my senses, the ship was already tilting. I grabbed for the door, which hadn’t jammed as of yet, and walked out on deck, realizing I didn’t have my life preserver, I went back into the room to get it. As I returned to the deck, they all seemed to be yelling, crying, and trying to get to their lifeboats. Most of the lifeboats were frozen solid or broken in the process of trying to get them loose.”

On board were four chaplains, all lieutenants. Only a few months previous, the Rev. George L. Fox (Methodist), Rabbi Alexander D. Goode (Jewish), Father John P. Washington (Roman Catholic), and the Rev. Clark V. Poling (Reformed Church in America) had become friends and ministerial colleagues during military chaplaincy training.

In the whirlwind of panic on the ship, the four chaplains from divergent faith traditions handed out life vests to the terrified young men. Refusing to take places on the lifeboats, they helped as many soldiers as they could to escape the sinking ship. As the supply of life vests ran out, each of the chaplains gave their own to four soldiers who were without.

Tragically, only two of the fourteen lifeboats were successfully deployed. The Dorchester sank in less than 20 minutes.

Witnesses report that the chaplains said prayers and sang hymns as they linked arms as the ship was sinking. “When she rolled, all I could see was the keel up there,” recalled Dorchester survivor James Eardley. “We saw the four chaplains standing arm-in-arm … like they were looking up to heaven, you might say. Then the boat took a nosedive. It went right down, and they went with it.”

Another survivor had a similar recollection. “As I swam away from the ship, I looked back. The flares had lighted everything,” engineer Grady Clark testified. “The bow came up high and she slid under. The last thing I saw, the four chaplains were up there praying for the safety of the men. They had done everything they could. I did not see them again. They themselves did not have a chance without their life jackets.”

Of the 902 passengers, only 230 survived.

There is no way to adequately measure what the efforts and sacrifices of the four chaplains meant on that night. Pfc John Ladd, a survivor, said that seeing their selfless actions was “the finest thing I have seen or hope to see this side of heaven.” For nearly eight decades, the story has been a symbol of counterintuitive sacrifice, faith-based cooperation, and remarkable love.

Dating back to 1946, the comic book, Chaplains at War, tells the story of the four chaplains who sacrificed their lives for their fellow soldiers during the 1943 sinking of the Army transport ship Dorchester. It was on display at the Chapel of the Four Chaplains located at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Philadelphia, 2018. (U.S. Air National Guard photo by Master Sgt. Christopher Botzum.)

In 1944, the U.S. government posthumously awarded each chaplain the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart. In 1948, a postage stamp was released in their honor. In 1960, the U.S. Congress authorized the unique creation of the Four Chaplains’ Medal and awarded those four men posthumously with the recognition.

In 1988, a unanimous Act of Congress established February 3 as an annual “Four Chaplains Day.” There are numerous stained glass memorials, plaques, paintings, and sculptures to their courageous act found at places such as the Pentagon and West Point.

One of the deceased clergymen was the Rev. George L. Fox – the Methodist chaplain. Prior to the fateful night, he had valiantly served in World War I. As an Army ambulance driver, he gave his gas mask to a wounded French soldier. In addition to other commendations, Fox was honored with the French Croix de Guerre, or Cross of War. After the war, Fox became a Methodist minister. Despite having lung damage from World War I, Fox volunteered for service again after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. “I have to go,” he told his wife. “I know what those boys are up against.”

For Fox and his fellow chaplains, devotion to God manifested itself as selfless service to those in need.

Floating in the freezing Arctic water after the explosion on the Dorchester, Private William B. Bednar heard “men crying, pleading, praying. I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going.”

“To take off your life preserver, it meant you gave up your life,” said survivor Benjamin Epstein in the Pioneer Press. “You would have no chance of surviving. They knew they were finished. But they gave it away. Consider that. Over the years I’ve asked myself this question a thousand times. Could I do it? No, I don’t think I could do it. Just consider what an act of heroism they performed.”

Amazing grace for survivors. Through the efforts of David Fox, the nephew of the Methodist chaplain on the Dorchester, the memory of the story of the Four Chaplains has been preserved. In 1996, Fox rented a video camera and attempted to interview as many Dorchester survivors as possible. He ended up meeting 20 of the 28 known survivors. According to Fox, the first sergeant of the ship, Michael Warish, reported that the four chaplains had a remarkable camaraderie: “These men were always together.”

“Remember, this was 1943. Protestants didn’t talk to Catholics back then, let alone either of them talk to a Jew,” Fox told America in WWII. “And yet here they were, always together, and they loved each other. The men said it didn’t matter which service they went to, that the chaplains always made them feel welcome and cared for. They were remarkable for 1943, way ahead of their time.”

Kurt Röser, Ben Epstein, David Labadie, Senator Bob Dole, Dick Swanson, Walter Miller, and Gerhard Buske at the Reconciliation Ceremony with the Immortal Chaplains Foundation on February 14, 2000. Röser and Buske were aboard the U-boat; Epstein, Miller and Labadie are survivors of the Dorchester; and Dick Swanson was aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Comanche, which hunted the U-boat. Photo: Immortal Chaplains Foundation web archive.

Through contacts in Germany, Fox also reached out to the three remaining survivors of the German submarine U-223 that had fired the torpedo. “When I was interviewing the U-boat crew, they just would cry,” Fox recalled. “The men had never told their families this story. They realized that when they hit that ship, there were men dying. They cheered the first moment, and then it just got very silent, and they felt terrible after that. These were Germans – they were not Nazis – young boys, 17, 18, 19 years old, forced to do it or they would have been shot, pretty much like in the movie Das Boot. The U-boat crews did what they had to do, but they didn’t like it very much.”

Through a notable reconciliation effort by Fox and the Immortal Chaplains Foundation in 2000, survivors of the Dorchester met with the surviving crew of the German submarine. The men from U-223 had also known loss. The German submarine was sunk a year after the Dorchester attack.

Remarkably, two surviving German veterans arrived in Washington D.C. for a 2000 memorial ceremony and they wept openly after visiting the Holocaust Memorial Museum. The small group of both the American and German survivors were invited to the nearby home of Theresa Goode Kaplan, the then 88-year-old widow of Rabbi Alexander D. Goode who had died on the Dorchester.

“She shook the Germans’ hands, and accepted their expressions of regret for her husband and for her suffering,” reported The New Yorker. “When the room was silent, Gerhard Buske (U-223’s executive officer), produced a harmonica, raised his hands to his mouth, and blew out a slow, warbling rendition of ‘Amazing Grace.’ Everyone clapped. Then the room lapsed back into silence.”

Buske returned to the United States in 2003 to speak at a ceremony on the sixtieth anniversary of the Dorchester’s sinking. “We the sailors of U-223 regret the deep sorrows and pains caused by the torpedo,” he said. “Wives lost their husbands, parents their sons, and children waited for their fathers in vain. I once more ask forgiveness, as we had to fight for our country, as your soldiers had to do for theirs.”

Buske concluded by imploring the gathering to follow the example of the four valiant chaplains. “We ought to love when others hate; we ought to forgive when others are violent,” he said. “I wish that we can say the truth to correct errors; we can bring faith where doubt threatens; we can awaken hope where despair exists; we can light up a light where darkness reigns; that we can bring joy where sorrows dominate.”

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News. This article originally appeared in the January/February 2022 issue of Good News. Readers can learn more about this story from the Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation at www.fourchaplains.org.

by Steve | Jan 7, 2022 | January/February 2022, Magazine Articles

Stained glass of John Wesley at the World Methodist Council Museum, formerly at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina. Photo by Steve Beard.

In honor of the passing of our friend Dr. William J. Abraham, we are republishing an address he presented at the 1995 national gathering of the Confessing Movement Within the United Methodist Church in Atlanta.

By William J. Abraham –

One of the most heartening features of life in the United Methodist Church is the deep yearning for renewal that can be detected at almost all levels of the church. In the patchwork of renewal movements within the United Methodist Church, the Confessing Movement focuses quite deliberately on the need for our denomination as a whole to be faithful to the deep doctrinal treasures of the church across the ages which are spelled out so clearly in the Articles of Religion, The Confession of Faith, and in Wesley’s Sermons and Explanatory Notes on the New Testament. Equally, it calls the church to lift high these doctrinal treasures for the whole life of the church in evangelism, liturgy, mission, pastoral care, social action, and every aspect of the work of the church. Implicit in this call to fidelity, reform, and renewal is the judgment that we have neglected these doctrinal treasures or, more seriously, that we have replaced these treasures with alien doctrinal material, which distorts our tradition, which separates us from each other and from the classical faith of the church, and which undermines crucial aspects of our life and mission together.

Why do we need a confessing movement? There are at least four very substantial reasons.

1. The substance and content of the faith have been called into question in our culture and more conspicuously within the church at large.

We are aware that our culture has become radically more and more pluralistic during the last generation. This is something we neither condemn nor applaud. In the providence of God we are called to serve the gospel at a time of momentous changes. God has sent us forth into a free marketplace of religions, ideas, fads, philosophies, and ideologies. In these circumstances, it is patently clear that we can no longer depend on the culture to transmit Christian faith in the public institutions of the land, such as the law, the news media, the academy, and the public education system. On the contrary, we can expect vigorous engagement in the public arena, if not downright hostile attack. We are not surprised, then, when we find the essentials of the faith called into question by intellectual leaders and scholars.

It is another matter entirely, however, when the faith of the church expressed in our doctrinal standards is called into question by those who want to remake or reimagine the faith in ways which repudiate the great classical doctrines of the church universal. There are those who want to displace the revelation enshrined in the Scriptures by attempting to replace it with an appeal to various forms of reason and experience. There are those who want to reject or set aside the Scriptures because they have invented their own canon. There are those who openly repudiate the Trinity because it is believed to be linguistically oppressive. There are those who reject the full divinity and humanity of Jesus Christ because they think it is supernaturalistic or incoherent. There are those who repudiate the atonement wrought by Christ because they think it is a case of divine child abuse. There are those who reject the universal saving work of Jesus Christ because they think they can save themselves with their own religion. There are those who repudiate the evangelistic and missionary activity of the church because they find it too offensive and intolerant in a pluralistic world. There are those who want to set aside the quest for righteousness and holiness because it does not fit with the mores of a new generation.

In these circumstances it is imperative that the church be clear about its core doctrines concerning the Trinity, the full divinity and humanity of Jesus Christ, and the complete sufficiency of God’s saving action in Christ. In these circumstances silence is a form of collusion. There is at this moment in history a clear need for the church to confess boldly and clearly the faith by which it lives and dies.

2. As a church we have in reality been committed to a form of practical, doctrinal incoherence for a generation or more.

Throughout the last generation the UM Church has been suffering from an acute case of doctrinal amnesia and of doctrinal dyslexia. I have chosen these images very carefully. In the case of amnesia the analogy is self-explanatory. We have simply forgotten our doctrinal heritage and hence have ignored its rich treasures and reserves. In some respects, however, the analogy with dyslexia is more compelling. As anyone suffering from dyslexia knows, the crucial problem is that one sees the relevant marks on the page but the marks are ingested in a distorted fashion. In the case of doctrinal dyslexia, what happens is analogous to this condition. In our case what has happened is that we have turned inside out and upside down the crucial material on doctrine in the Book of Discipline. We have displaced the actual standards of doctrine laid out in the Constitution by concentrating on the highly speculative material laid out in the section on our theological task.

At a crude and popular level we have replaced the great doctrinal verities of the faith, which are laid out so carefully in the Articles of Religion, The Confession of Faith, and in Wesley’s Sermons and Explanatory Notes on the New Testament, with the famous Methodist “quadrilateral.” We have replaced commitment to the great doctrines of the church with a commitment to a speculative theory of religious knowledge. We have replaced content with process, sacrificing the possibility of a publicly agreed common mind to the actuality of a partisan, conjectural theological method.

The Rev. Dr. William J. Abraham speaks at the Fourth Global Gathering of the Wesleyan Covenant Association in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in November 2019. Photo: Mark Moore

The consequence is that our identity is now shaped by an interesting but dubious exercise in religious theory of knowledge. On pain of denying our tradition, we are forced to confess adherence to a piece of clever epistemology which was worked out in the 1960s and which is at odds both with Wesley and with the clear content of the constitutional standards of doctrine. In these circumstances the great classical doctrines of the faith, to which Wesley wholeheartedly adhered, are treated as optional alternatives to be received, rejected, remade, or reimagined at will. We have idolized a piece of philosophical speculation and are now reaping the consequences. Not surprisingly, we find ourselves torn asunder by conflicting doctrinal proposals. The quadrilateral effectively fosters this situation. It invites us to evaluate our beliefs and doctrinal suggestions by running them through Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. As a pedagogical device, the quadrilateral indeed has merit. Anyone who is a teacher can testify to this. However, as a formal proposal in the field of religious knowledge, the quadrilateral is an absurd undertaking, for only an omniscient agent could seriously undertake to run our proposals through the gamut of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. Only God could use the quadrilateral and, thankfully, God does not need it. What actually happens, of course, is that folk make a good faith effort to meet this grandiose standard, but the considerations are so diverse and complicated that the result is a wild array of alternatives. The quadrilateral is much like a kaleidoscope. Each time you shake Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience, a different configuration emerges. The result is doctrinal chaos and incoherence. Even Albert Outler, the great architect of the Methodist quadrilateral, was disturbed by its misuse, and late in life expressed reservations about its logic.

This, of course, is what we get when we use the quadrilateral at its best. At its worst, our use of the quadrilateral is like a lateral in football; if you cannot support your position by one element in the quadrilateral then use a lateral pass to tradition, reason, or experience until you get the support you need. In this instance the quadrilateral is simply a camouflage for any and every doctrinal proposal. It is clearly at odds with the much more modest and nuanced appeal to Scripture carefully stated in the Articles of Religion and The Confession of Faith.

It is in this whole arena that we need very significant reform. Currently, the self-image of United Methodists reflects non-commitment to any specific doctrines. At best it adheres to a version of the Methodist quadrilateral. Against this I want to suggest that the UM Church is a confessional church. We have a clear body of Christian doctrine spelled out in our doctrinal standards. Broadly speaking, these standards commit us to the classical faith of the church developed during the patristic period and the Reformation and laid out in the Articles of Religion and The Confession of Faith. Equally, they commit us to the Wesleyan distinctives laid out in Wesley’s Sermons and Explanatory Notes on the New Testament. Where we are currently required in practice to accept a speculative theory of religious knowledge, the UM Church in its Constitution invites us to accept and explore the rich treasures embodied in the classical and Wesleyan traditions. It is high time that we enter into a new doctrinal reformation which comes to terms with this historical reality.

3. Doctrinal considerations are foundational to virtually every aspect of our life and faith, and nothing short of this will challenge the internal secularization of the church as a whole.

The Methodist movement, which sprang up in the eighteenth century, was part of a profound spiritual awakening which cannot be understood apart from the deep gospel truths which animated its leaders and workers. Methodists laid hold of the faith of the church, opened themselves to the active presence of the Holy Spirit, found themselves gloriously converted, and were then propelled into a spiraling movement of evangelism and social action. This was clearly a mighty work of providence which depended on very specific doctrinal commitments such as we find in the doctrines of creation, redemption, grace, justification, and sanctification. Take away these doctrines and Methodism is unintelligible and unworkable. Doctrinal commitments inform and enter into our work in evangelism, worship, social action, pastoral care, ecumenism, and administration.

Increasingly, with the rise of various secular disciplines that reject or ignore theological considerations, there has been a marked tendency to envisage our work in entirely naturalistic, secular, or procedural categories. Worship is reduced to entertainment or to purely aesthetic dimensions; administration is reduced to the logic of management; social action is cast entirely in humanitarian categories; evangelism is interpreted primarily in terms of nominal church membership; pastoral care is cast in terms of therapy; the election of bishops is turned into political campaigning; preaching is reduced to moralism; prayer becomes a form of comfort and auto-suggestion; the Scriptures are reduced to a set of sacred texts; Christian theology becomes an exercise in philosophical or ideological speculation.

The issue of course is a delicate one, for all truth is God’s truth, and we are free, therefore, to baptize all sorts of material for use in the church. Only a fool would refuse to plunder the secular “Egyptians” of our day and generation. However, our first and primary identity in the church is that we are the Body of Jesus Christ, equipped with a whole tapestry of insight expressed in the great doctrines of the faith and overshadowed by the mystery of the living God. Hence, as United Methodists, we live in and for the kingdom of God, not some secular substitute. In our worship we are committed to the great sacraments of baptism and eucharist, where we look to the Holy Spirit to wash us from our sins and feed us with the bread of heaven. We read the Scriptures not as an exercise in sacred archaeology but as the living Word of God. In evangelism, rather than simply adding members to the church, we seek to let the Holy Spirit deliver us from the bondage of original sin. In social action, rather than pursue the ideals of this or that political party, we seek to let God’s rule enter every nook and cranny of our social existence. In pastoral care, we are committed to the cure of souls; in administration we are looking to the Holy Spirit to give the whole church all the gifts that are needed to be agents of the kingdom; in the election of bishops we are seeking to find the charismatic gift of oversight in the church as a whole; in prayer we are entering the very courts of heaven itself; in preaching we are proclaiming and expounding the Word of God; in Christian theology we are in faith seeking understanding.

Conceived in this fashion, our work in the church is encoded by doctrinal themes and convictions. It is not that we somehow conjure up a set of doctrines and then apply them to this or that element in the life of the church. Doctrine is built into the very conception and execution of our work together. In the face of the widespread secularization of our culture and the strong temptation to mimic the ways of the world, it is vital that we remain steeped in the doctrinal riches of the faith. In this way our life and work together can truly represent the action of the Body of Christ and be filled with the direction of the Holy Spirit. Hence we can by grace be a city set on a hill, an outpost of the kingdom of God, and a vineyard truly built of the Lord, rather than one more social club, or our favored political party at prayer, or an insipid nursemaid to the secular state.

4. There is a need to heal the deep alienation and the sense of intellectual exclusion which exists in significant segments of the church at large.

What is at stake here is far from easy to describe. Let me try as best I can. I will do so by providing a tendentious narrative which will deliberately exaggerate in order to make the crucial point at issue. Ostensibly, United Methodism is an open, inclusivist denomination. We have prided ourselves on welcoming the stranger, on providing a spiritual home for those who have felt they were oppressed in other traditions, and on being a community where people are free to think for themselves. Moreover, we have worked exceedingly hard to empower women and ethnic minorities. These are virtues which very few, if any, in United Methodism would want to forfeit.

Yet this is not the whole story. At the end of the last century, the leadership of the forbearers of modern United Methodism made a strategic decision that has never been adequately faced and worked through. At a time of enormous intellectual and social crisis, we opted to become the leaders of the liberal Protestant movement in North America. Believing that the classical Methodist tradition could not really be defended in the modern world, we adopted a revisionist pose which dismantled the classical faith of Methodism. Like the leaders in most mainline churches we lost our intellectual nerve and elected for massive accommodation to the intellectual elites of the culture.

This was an understandable decision, for liberal Protestants insisted that there was no other way to face the intellectual and social challenges of the day. Hence they felt that they could quietly ignore or dismantle vast tracks of the Christian heritage without shedding any theological tear. This shift – developed quite brilliantly, for example, at Boston School of Theology (which became a kind of Vatican of the tradition as a whole) – was taken as a given by much of the intellectual leadership of our tradition in the twentieth century. Any alternative seemed a perpetuation of a doctrinal dark ages which needed to be enlightened by all that was best in the modern world.

As a consequence, Methodism became theologically schizophrenic. Our roots, our hymnody, our founding documents were wholehearted steeped in the classical Christian tradition, but many of our leaders have been deeply alienated from this whole heritage, even though they had to work overtime to provide a semblance of intellectual coherence for themselves. Over time the fortunes of liberal Protestantism have waxed and waned. Liberal Protestantism was deeply challenged by the rise of Neoorthodoxy before and after the Second World War, but this was relatively easily contained by arguing that the work of Barth and the Niebuhrs was really a moment of self-correction in the development of liberal Protestantism. It was, for a time, given bad press with the arrival of the “God is dead” movement of the 1960s, but this was more of a media event than it was a serious threat to the standing orders of the great liberal Protestant experiment. Overall, during this period the intellectual institutions of United Methodism were a closed shop. It was the exception rather than the rule when someone who was committed to the classical faith of the church was permitted entrance. Too often they were dismissed doctrinally as intellectual illiterates.

As a consequence, many faithful United Methodists were shut out of crucial centers of the church’s life. They did what any group will do under such circumstances: they became frustrated, angry, fidgety, and alienated. Being what all United Methodists are, namely, inveterate, pragmatic activists, they also went to work. Over time they funded and built their own institutions, set up their own parachurch organizations and caucuses, got themselves educated, printed their own literature, held their revival meetings at the grass roots, set up an alternative mission society, and above all, poured themselves into evangelism and church growth. At the same time they worked as best they could within the system, being as loyal as they knew how to the church whose faith they treasured.

Liberal Protestantism is again in serious trouble within the academy. It is challenged on one side by the development of various forms of radical Protestantism and on the other side by a resurgent recovery of evangelical and patristic sensibilities in theology. Some academic institutions have even opened their doors, albeit in fear and trembling, to those who do not share the revisionist agenda. The ethos of liberal Protestantism, however lingers on in the tradition as a whole. Almost all have been preoccupied by a multicultural agenda that focuses on a form of diversity which masks deep opposition to the classical faith of the church on the grounds that it is incredible and oppressive. The inevitable consequence has been that many conservative and traditional United Methodists remain deeply alienated within the tradition as a whole.

We need a vigorous confessing movement at this moment in our history in order to give voice to those who have been systematically excluded from the central life of the church. Members who are committed to the classical doctrines of the faith need to know that they are not alone, that there are others who share their exclusion, that they can be fully Christian within the United Methodist tradition, and that they can learn and relearn the classical faith of the church. In short, there are many within United Methodism who need a space where they can be healed and intellectually renewed to serve the present age. They need a movement in which they can own their own tradition with integrity and deepen their hold on the doctrinal treasures of the church.

Our concern is with doctrine. Without adequate attention to this crucial dimension of our life together we will become antinomians, pharisees, and intellectual anarchists. Worse still, we will become emotionalists, frenetic activists, and even apostates from the faith once delivered to the saints. With proper attention to doctrine we will continue to be part of that great succession of evangelists, saints, and martyrs who, in the church catholic across the ages, have borne a faithful testimony to our great God and Savior Jesus Christ.

This essay was published in the January/February 1996 issue of Good News.

We are heirs of God’s promises to Abraham, and we are included in God’s blessed people. And just as God called Abraham to faithfulness and obedience, God also called the church. As children of Abraham and sons and daughters of the King, we’ve distorted the story of the perfect gospel to be a ticket to heaven – or else.

We are heirs of God’s promises to Abraham, and we are included in God’s blessed people. And just as God called Abraham to faithfulness and obedience, God also called the church. As children of Abraham and sons and daughters of the King, we’ve distorted the story of the perfect gospel to be a ticket to heaven – or else.

There are seven activities a week, each one about two hours long. They have movie nights three times a month, always with an upbeat theme.

There are seven activities a week, each one about two hours long. They have movie nights three times a month, always with an upbeat theme.