by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Front Page News, Sept-Oct 2022

By Kevin M. Watson

Almost all of my writing for the church and the academy has focused in one way or another on the Wesleyan theological tradition. From time to time I am asked: Why are you Wesleyan?

When I was in seminary, I remember experiencing some shock at the wide array of opinions and denominations represented by faculty, students, and the assigned readings. I wrestled with what I was going to do when I graduated and began serving in full-time local church ministry. The models I saw seemed to focus on endlessly exploring ideas across a very broad swath of Christianity. The questions were often good and interesting, but they seemed to always lead to more questions. As someone preparing to pastor a local church, I was pretty sure God was calling me to offer the truth about Jesus Christ and his gospel. I needed to work through the questions to return to truth I could proclaim with confidence to the people God sent me to serve.

I eventually came to a place where I realized the best way I could proclaim the truth was by being deeply anchored in the theological heritage of my particular part of the Body of Christ.

This conviction came as I was taking United Methodist History and Doctrine with Dr. Doug Strong, who would become one of my most important mentors (and my first boss in the academy when he hired me for my first faculty position at Seattle Pacific University).

Doug’s passion for the Wesleyan theological tradition became my passion. He taught Methodist History and Doctrine by anchoring us in the writings of John Wesley. We read Wesley’s sermons and several other occasional pieces he wrote. We studied the basic practices of Methodism. I learned, among other things, that Wesley’s followers were called Methodists because of the methodical pursuit of a particular way of life.

Two things that happened in that class that are crucial for why I am Wesleyan today.

First, I read John Wesley’s teaching on entire sanctification and Christian perfection. I was captivated by Wesley’s optimism of what God can do in our lives through the power of the resurrection of Jesus. I was excited and energized by Wesley’s focus on the importance of salvation and his emphasis on the way of salvation, a journey with God that one grows in with expectation of seeing God deliver from bondage to sin and bring victory in Jesus’s name.

In short, entire sanctification is the Christian belief that the grace of God saves us to the uttermost, freeing us not only from external sins but bringing holy affections, holy tempers. Entire sanctification is loving God and neighbor to the exclusion of sin.

As I’ve spent time with this teaching, I’ve become more convinced that entire sanctification is true. It is powerful! When I speak to leaders in Wesleyan communities, I often say something like this: “There should not be a church in any of your communities that has a more bold and audacious optimism of what the grace of God can do in the lives of every single person in your communities than your church.” My intention in saying this is not to stir up unhealthy and unhelpful competition or strife between denominations. Rather, it is to call the followers of John Wesley back to the riches of their own heritage.

There are two key passages that capture this Wesleyan essential for me. The first is from John Wesley’s sermon, “The Scripture Way of Salvation”:

“But what is that faith whereby we are sanctified, saved from sin and perfected in love? It is a divine evidence and conviction, first, that God hath promised it in the Holy Scripture…. It is a divine evidence and conviction, secondly, that what God hath promised he is able to perform…. It is, thirdly, a divine evidence and conviction that he is able and willing to do it now…. To this confidence, that God is both able and willing to sanctify us now, there needs to be added one thing more, a divine evidence and conviction that he doth it.”

After defining the faith by which we are entirely sanctified, Wesley then asks, Should we expect to receive entire sanctification gradually or instantaneously? This passage gets me every time!

“Perhaps it may be gradually wrought in some … But it is infinitely desirable … that it should be done instantaneously; that the Lord should destroy sin ‘by the breath of his mouth’ in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye. And so he generally does, a plain fact of which there is evidence enough to satisfy any unprejudiced person. Thou therefore look for it every moment…. And by this token may you surely know whether you seek it by faith or by works. If by works, you want something to be done first, before you are sanctified. You think, ‘I must first be or do thus or thus.’ Then you are seeking it by works unto this day. If you seek it by faith, you may expect it as you are: and if as you are, then expect it now. It is of importance to observe that there is an inseparable connection between these three points – expect it by faith, expect it as you are, and expect it now!… Christ is ready. And he is all you want. He is waiting for you. He is at the door!” (John Wesley, “Scripture Way of Salvation”).

The second passage is from Scripture itself, and is one of the crucial passages in Scripture regarding entire sanctification:

“This is the will of God, your sanctification… May the God of peace himself sanctify you entirely; and may your spirit and soul and body be kept sound and blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. The one who calls you is faithful, and he will do this” (1 Thessalonians 4:1-3; 5:23-24).

I am a Wesleyan because I believe that God wants to sanctify everyone who has faith in Jesus Christ and not just a little bit, but entirely! This is God’s will. And God, who calls us, is faithful and will do this!

The second thing that happened to me when I was in seminary that is a major reason I am not only Wesleyan, but got a PhD and became passionate about preparing people for leadership in the church, was that I was invited to join a Wesleyan band meeting. When I was invited, I did not know what it was. But I knew I was in seminary because the Lord had called me to give my life to Jesus and his church and I knew I was moving away from that calling and I didn’t know where to turn.

A band meeting is a small group of usually three to five people focused on confession of sin in order to grow in holiness. It is grounded on James 5:16, “Therefore confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another, so that you may be healed. The prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective.”

Joining a band meeting was one of the hardest things I have ever done. It was also one of the most important things I have ever done. We confessed our sins to one another, not in order to brow beat each other, or to shame one another, but in order to receive forgiveness through the grace of Jesus and in hope and expectation of experiencing healing and transformation.

The highlight of the group was when someone finished their confession and someone else shared words of forgiveness and pardon over them. We often used the words from 1 John 1:9, “If we confess our sins, he who is faithful and just will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.”

My life was changed because of my participation in a band meeting. This led me to study the history of the band meeting in early Methodism. It motivated me to write to help contemporary Wesleyans reclaim this practice, as well as the class meeting. The class meeting was a small group of about twelve people that was required of all Methodists throughout John Wesley’s lifetime and for the first several decades Methodism was a formal denomination in the United States (the Methodist Episcopal Church). The class meeting was less intense than the band meeting, focusing on a question like, “How is it with your soul?”

I am a Wesleyan because I have experienced the fruit of the method of Methodism. I am Wesleyan because I am captivated by the hopeful and optimistic theology which believes that the power of the resurrection of Jesus Christ is greater than sin and even death itself. Even in the times when I have been most discouraged by the state of the contemporary church, I still believe God wants his people to unplug the old wells that were dug by the first Methodists. I am convinced there is still living water there.

One last thing: I am a Wesleyan not because I want to be known as a follower of John Wesley. I do increasingly see John Wesley as the spiritual father of the Wesleyan/Methodist family. But Wesley was not interested in making little John Wesleys. He wanted to help people follow Jesus Christ. I am Wesleyan because it is the best way I know to follow Jesus Christ, to grow in holiness of heart and life.

More than being Wesleyan, I want to be a real Christian. The more I preach the gospel with a recognizable Wesleyan accent, the more effective I believe I will be in following Jesus Christ, my Lord and Savior.

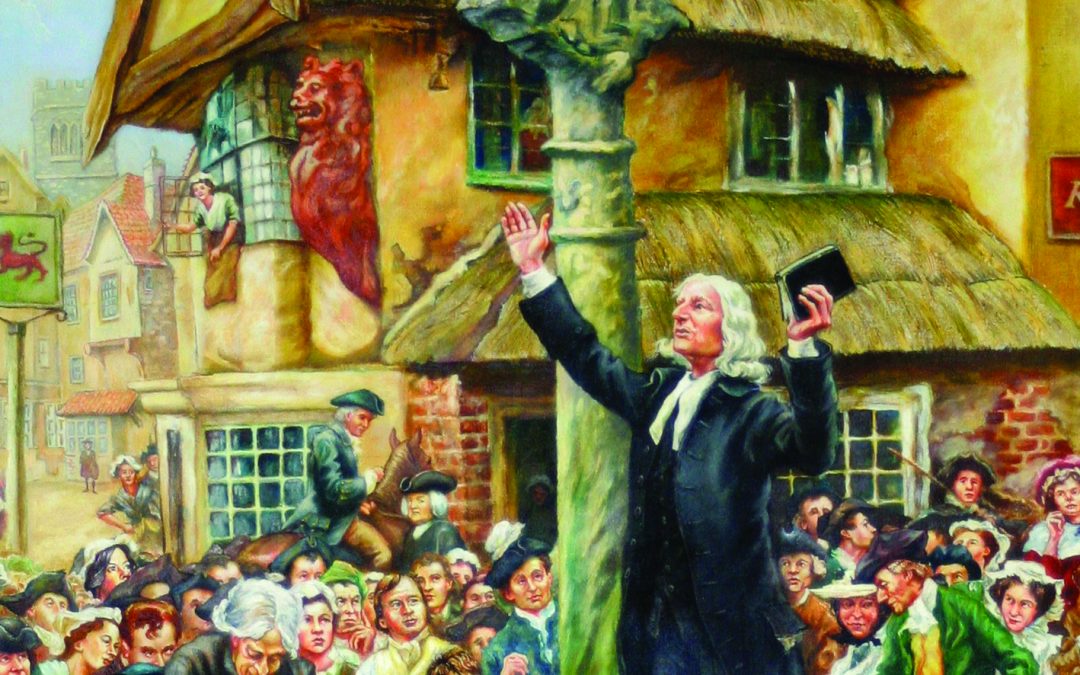

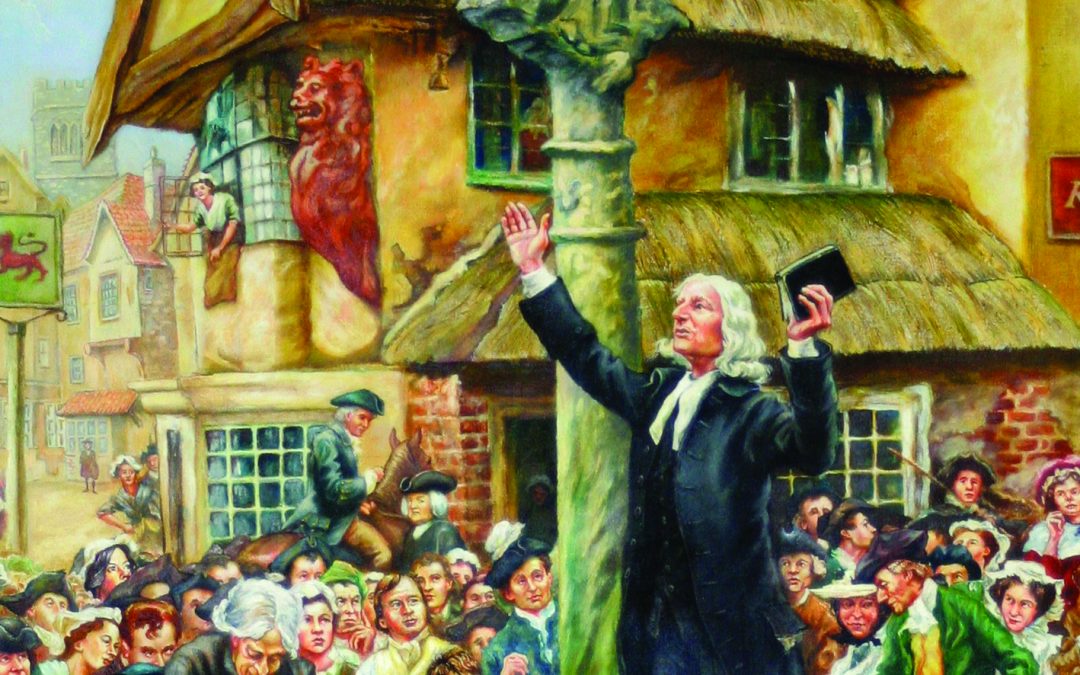

Kevin M. Watson is Acting Director of the Wesley House at Baylor University’s George W. Truett Theological Seminary in Waco, Texas. He is also Associate Pastor of Discipleship at First Methodist Church Waco. Dr. Watson is author of numerous books including The Class Meeting, Pursuing Social Holiness, Old or New School Methodism?, and Perfect Love. Prior to his position at Truett, he served as Associate Professor of Wesley and Methodist Studies at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. Image:

“John Wesley Preaching at the Market Cross” by Richard Douglas. This is a color version of an earlier illustration by William Hatherell (1855-1928). It is part of the Richard Douglas collection of paintings at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Sept-Oct 2022

By Kimberly Constant

The book of Psalms stands at the heart of Scripture as a unique offering in the biblical canon. Whereas the other books of the Bible contain the divinely inspired words of human beings written for the benefit of other human beings, Israel’s ancient book of worship holds the words of human beings written for the benefit of God – words that continue to offer profound insight to modern day believers. The psalms serve as a key to tapping into the deep intimacy inherent in an authentic relationship with God.

When I think of the psalms, immediately Psalm 139 springs to mind. It begins with a beautifully phrased exploration of God’s intimate knowledge and love of the psalmist. Anywhere he goes, there the psalmist finds God. But the psalmist’s words quickly take a dark turn in verse 19 with a call for vengeance against the enemies of the Lord. So stark is the contrast in content and tone that we rightly wonder about its origins. How can such a violent expression of hatred have a place in the Bible? How can these words constitute worship? What do they mean for Christians? Aren’t we called to love? Aren’t we called to make peace? Do such expressions of anger really have a place in our relationship with God?

Surprisingly, the candor of Psalm 139 is not an anomaly. Within the psalter we discover similar calls for vengeance, as well as cries of deepest distress and expressions of anger so vivid that we recoil in shock. These are interposed with more palatable words which speak of green pastures and wings of refuge, or shouts of praise springing forth from all creation, imagery that appears more aligned with Jesus’ call to love God and others. Yet the book of Psalms tells us a story that challenges us to let go of any illusions that such love must only be bright and sunny or that our worship must be sanitized. Instead, the book of Psalms offers us an unflinching representation of the full range of human emotions extended to God as authentic worship.

Truthfully, this is the kind of worship we need at this moment in history in which our collective anger and pain threatens to rip society apart. The book of Psalms offers believers a way through this quagmire, a way to give voice to our deepest feelings as an act of release to God.

The words of the psalms encourage us to rightly rail against the injustices of a fallen and broken world, to genuinely grieve amidst the deep sorrows of life, and to joyously celebrate the victories of faith when they come, but to do so with humility, recognizing our limitations and putting our trust not in ourselves to right these wrongs, but in God. We make room in our hearts so that God can fill us with his divine strength. The very act of reading the Psalms, as words directed to God, allows us to become participants in this kind of genuine worship and relationship.

As we read these ancient prayers and praises, we join with them our own and a holy conversation ensues. So perhaps now is the time to heed the invitation offered by the psalmists – as individuals, but also as a larger community of believers, to commit to incorporating reading the psalms into the daily rhythm of our spiritual practices.

But where to begin? How to make sense of these ancient words? First, with a pledge to engage in a diligent and respectful reading of each psalm on its own terms. To do so we need a general understanding of some features of the psalter. The book contains 150 psalms, which are poems or hymns of worship, divided into five smaller books.

• Book 1 (Psalms 1–41)

• Book 2 (Psalms 42–72)

• Book 3 (Psalms 73–89)

• Book 4 (Psalms 90–106)

• Book 5 (Psalms 107–150)

Although each psalm is unique, we can trace a subtle overarching message in the book of Psalms – a trajectory representative of the evolution of the faith of the Israelites, and hopefully we readers as well.

The psalter begins with two psalms which serve as an introduction for its entirety. They are bookended with the Hebrew word we translate as happy or blessed. Psalm 1:1 attests that the person who delights in God’s ways and is obedient to them will be happy, and Psalm 2:12 closes with the statement that happiness comes when we take refuge in God. These two concepts of obedience and refuge become the means by which the Israelites ultimately will navigate the difficulties that lie ahead. Books One through Three of the psalms thus generally trace the erosion of faith that occurred in Israel during the time of the monarchy, culminating in the somber final verses of Psalm 89, which reflect on the devastation of Israel’s exile and the seeming withdrawal of God’s presence. The response to this national sorrow occurs in books Four and Five, which turn the focus to God as the true king.

Book Four opens with a psalm that is attributed to Moses. The mention of his name mirrors the words of the psalmist in recalling a time in which Israel did not have a human king but instead relied on God alone. Hence the final two books of psalms encourage the people to trust and take refuge in God, rather than any human king or leader, through obedience to God’s law.

Finally, the psalter concludes with five psalms of praise pointing to an ultimate victory for those who remain faithful. Although not every psalm will fit this overarching pattern, determining a psalm’s location within this grand narrative provides a helpful starting point.

Next, the reader might consider the genre of each psalm. Most frequently we encounter laments, often thought of as the backbone of the psalter. Typically, a lament begins with an address, followed by a complaint, a plea for God’s help, an assertion of the psalmist’s trust in God, and a concluding vow of praise. We also find psalms of praise, thanksgiving, psalms which focus on the human king of Israel, psalms which focus on God as king, and wisdom psalms. Some appear to fit into more than one of these categories. Further, some of the identifying features of these psalms are missing or truncated, making categorization difficult at times. Nonetheless, an attempt to identify the genre of an individual psalm helps us understand potentially challenging aspects. For instance, the deep anger in Psalm 139 represents the complaint aspect of a psalm of lament. It is followed by a plea and implied assertion of trust in God in verses 23-24. Having rightly expressed anger at the deep injustice of his world, the psalmist ultimately puts his trust in God and focuses not on his pain, but on his relationship with the Lord.

Finally, as with all poetry, modern or ancient, the form and the function of the psalms also contribute to their meaning. Difficulties abound in this type of analysis due to the elements lost in translation from the original biblical Hebrew. But there are a few features worth noting. One of the more common elements in the psalter is the use of parallelism in which one line of the psalm corresponds in some way with the line that follows. Repeated words or phrases often accompany this device. In addition, the psalms make use of metaphor and simile, hyperbole, and personification. These mechanisms can be a means to capture the reader’s attention, while also allowing the writer a measure of artistry. Often, they highlight the mood and the emotions of the psalmist.

Thus, a conscientious reader can begin a study of a psalm by asking a few basic questions:

1. Where is this psalm located within the overarching narrative of the psalter?

2. What type of psalm am I reading?

3. What stands out in terms of the form, function, or language of this psalm?

4. What mood and emotions does the author invoke in this psalm? Does the psalmist experience a shift in these or does the tone remain the same?

5. Finally, how do all of these illumine the meaning of the psalm?

Lastly, we engage with the psalms through the process of applying our interpretation. Asking ourselves questions such as, “What do I learn about God and God’s work in the world from this psalm?” Or, “How does this psalm lend insight to my role in serving God?” Since the psalms are words directed to God, we might engage in the practice of praying the psalms also, substituting our own prayers and praises when appropriate. Or replacing the psalmist’s “I” or “we” with our own names or the names of those on our prayer lists as we read.

Finally, we would do well to recognize that reading the psalms as a spiritual discipline involves taking the time to savor each psalm. Perhaps reading one psalm in the morning, and one in the evening – as a prayer or devotional exercise, or even listening to it via a Bible app and allowing the words to wash over us. If all of us readers of Good News magazine were to commit to such an exercise, we would read the entire book of Psalms in 75 days. That would be two-and-a-half months of committed reflection, prayer, and worship done in concert with one another and with all the voices of those who have walked the path of faith before us. One can only imagine what God might do, the transformations that might occur, with such an offering of time and commitment.

Ultimately, the psalms encourage us to cultivate a genuine relationship with God, reassuring us that our deepest cries will be met by a God who loves us unconditionally. The God who, according to the psalmist, formed us together in the secret place. The God who spoke the universe into existence. The God who rescued the enslaved Israelites from Egypt and against all odds formed them into a priesthood of believers. The God who continued to extend grace and mercy even when those same people turned from him to pursue their own desires. And as we who live on this side of the cross know, the God who sent us Jesus Christ that we might be free from the chains of sin and death forever.

The world seems on the verge of exploding with anger, confusion, and despair. But we as believers need not meet that fate. Our God beckons us to bring all our feelings to the foot of God’s throne. To offer them up as an act of worship so raw and authentic that all pretense falls away. That in the place of such vulnerability, God might meet us and strengthen us, cultivating within us the deep trust and obedience necessary to genuinely love God and others.

Kimberly Constant is a Bible teacher, author, and ordained elder in the United Methodist Church. You can find out more about Rev. Constant at kimberlyconstantministries. Image: Shutterstock.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Sept-Oct 2022

By Shannon Vowell

Many of us picture God the Father based on artistic representation or a beloved earthly father. Our ideas about Jesus can take their cues from Scripture’s description of him. But how do we understand/visualize God the Holy Spirit? Since Pentecost, God has been present to believers – abiding in us, encouraging us, empowering us, directing us. We are temples of the Holy Spirit. Astonishing.

As a new believer, getting to know the basics of the Father and Jesus was mostly a matter of time in Scripture. Learning the truth of the character of the One God as expressed in those two Persons – that was a joyful adventure of discovery for this book-nerd.

But the Holy Spirit? It seemed to me there was no coming to grips with a Person of the Godhead who wasn’t, well, a person.

It didn’t help that my first Bible was an older translation, in which “Holy Spirit” appeared as “Holy Ghost.” A bad habit of horror-movie-watching when I was a teenager predisposed me to cover my eyes at the mention of anything “ghostly.” Honestly, I wasn’t sure I wanted to get better acquainted with this aspect of God.

Beyond my ghoulish, “things that go bump in the night” phobia about ghosts, I struggled with the concept of “spirit.” I discovered that the Greek word for “spirit” was the same as the word for “breath” – pneuma, from which we get our English “pneumonia.” My sister had almost died of pneumonia when we were young. Why would I want to get to know God in the guise of collapsed lungs?

Bottom line, the Holy Spirit seemed to me both nebulously scary and completely confusing.

At such places of fear and confusion, I find that gravity helps me a lot. How so? Because I don’t “get” gravity, either. I don’t understand the principles by which I stay fixed to the surface of a planet that is whirling through space. I don’t understand why rockets have to “break free” from the atmosphere, nor why astronauts weigh less on the moon. The whole thing mystifies me – and totally freaks me out if I think about it too much.

Gravity goes on holding me to earth, though. My comprehension has no bearing whatsoever on its efficacy; me freaking out matters not a whit. Like gravity, God keeps working perfectly without my comprehension (or my permission).

Even better, neither God nor gravity relies on me. For anything. But both God and gravity can be relied on, by me, even in the absence of my “getting” them. What a relief!

In fact, in the un-gettable-ness of God, I have an ongoing reminder of my true identity: God’s child, not “god” myself. I am not responsible for the Universe. I cannot “save” anyone – not even myself – but that’s not my job. When I put my trust in the goodness of the God I cannot comprehend, that place of surrender becomes my custom-fit haven. Rather like this planet, onto which gravity holds me so faithfully, is my custom-fit home.

The liberating truth is that I am not going to fly off into outer space, because I am held safely by the One who made me, and gravity, and outer space, and everything! “For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him” (Colossians 1:16).

If gravity has the power to hold us secure on terra firma, the Holy Spirit has the power to lift us to heavenly heights at the same time. Gravity exerts “natural” power; the Holy Spirit is supernatural power. Gravity keeps us physically anchored in the present moment; the Holy Spirit gives us glimpses of eternity and empowers us to live “now” with the “not yet” resident in our very beings.

We see this power especially clearly when the Holy Spirit catalyzes transformation in disciples of Jesus at Pentecost. The second chapter of Acts contains so much that is startling that it’s easy to miss the central miracle: Peter, the cowardly Christ-denier, preaching the gospel to a crowd of thousands in the very city where his Lord had been condemned! The Holy Spirit falling on him had not just loosened his tongue to miraculously speak in other languages – the Holy Spirit had redefined his identity: terrified fisherman to fearless apologist.

The apostle Paul’s transformation – from malevolent persecutor of Christians to church-planting / New Testament martyr for the faith – follows soon thereafter (in Acts 9).

These two men’s experiences exemplify the action of the Holy Spirit in the lives of believers: unmistakable change, undeniable urgency, inexplicable effectiveness – supernaturally.

Those who claim that such miracles of transformation are no longer part of Christian experience are missing out on God’s gifts. Lives are still changed, in ways just as radical as Peter’s and Paul’s! Here are a few examples from my own acquaintanceship: my friend Bob, who went from sleeping off Saturday nights every Sunday morning to leading ministries at his church; my friend Lisa, whose legendary sharp tongue and bitter mindset were replaced by sparkle-eyed kindness and evangelical energy; my friend Don, whose decades of alcoholism almost killed him but who walks now in a sobriety so joyful and Jesus-focused that he inspires other long-time drunks to give God a try. These are real people, living in real freedom, thanks to the reality of the Holy Spirit!

Paul encourages disciples not to be “conformed” to the pattern of the world, but rather to be “transformed” by the renewing of our minds (Romans 12:2). Only the Holy Spirit can enable us (as Paul was enabled) to believe that such transformation is possible. And only the Holy Spirit can enable us (as Peter, Paul, and countless others have been enabled) to live into that amazing paradigm of supernatural change.

Sharon Vowell, a frequent contributor to Good News, blogs at shannonvowell.com. This is the third of three installments on the Trinity from her new workbook entitled Beginning … Again: Discovering and Delighting in God’s Plan for Your Future, available on Amazon. Image: Mosaic of Pentecost. Photo taken by Holger Schué, Pixabay.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Sept-Oct 2022

By Terry Teykl

“Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them” (John 7:37).

For many years, I have taught about the parallels between rivers and aspects of prayer. For example, rivers bond us geographically and historically to other people, giving us a place in the bigger picture of life. Year after year they pour out of the headwaters and flow across vast regions of land eventually pouring into the vastness of the ocean. Rivers are rich in history and are speckled with events that have shaped nations. Likewise, the river of prayer is connected. The life of God has flowed from its headwaters through time and history. All prayer empties into the vastness of God. He is like an ocean compared to the volume of rivers in the world.

Rivers are in many ways exciting and playful, meant to be enjoyed minute by minute. Their past and future are important, but what really matters now is the pleasure they provide us. They offer us an unlimited supply of recreation and refreshment up and down their banks. Similarly, the river of prayer is now. God is able and willing to help us if only we ask. Prayer is effective when “on sight with insight,” reaching out to immediate and felt needs of the moment. We must be ready to pray at any time and place so that God can pour out his love and meet needs on a day-to-day basis.

Rivers are life giving. They infuse everything they touch with energy and vitality. They provide essential nutrients and water for plants and animals in and along their banks. There are over 3,000 species of fish in the Amazon River. Civilization seems to prosper in relation to rivers, which provide many things like transportation for people and their products. Likewise, the river of prayer is life giving. It is the source through which the love and mercy of God has flowed. Deeply relational, prayer touches the hearts of those who are hurting with the salve of God’s grace and unconditional acceptance. Centuries bear witness to this through the acts of intercession when people pray and stand in the gap for those who are lost and plead their cases before the Father until his purposes are fulfilled in their lives. The sheer volume of this river is the rich and never-ending love of God.

Rivers are mysterious – sometimes hidden beneath the earth’s surface, and sometimes flowing on top – they are incomprehensible and esoteric. What lies beneath them is unknown. We never completely understand what makes a river flow fast and slow, wide and then narrow. We can never grasp how a river can cut and form the Grand Canyon with immense size and beauty. As you look at the history of prayer, we realize how mysterious it is. During the monastic years prayer seemed to flow less visible as in the practice of solitude. Yet, it flowed all the same to merge in public expressions of prayer. Prayer is so simple yet opens us to the experience of his presence and exalts him in his majesty.

Rivers are cleansing. Always flowing downstream, rivers are nature’s own waste removal system. They eliminate contaminants from the earth and carry them to the ocean. The rushing waters of a mountain stream can be abrasive, smoothing and refining stones as it continually rubs against their jagged surfaces. Rivers have no discretion; they confront everything in their path, carrying away anything which is not secured. Prayer is also cleansing. The river of prayer is vital in spiritual warfare. Satan is a dangerous foe and prayer in the name of Jesus is our main weapon. Through prayer we have the power and authority to enforce the rule and reign of Jesus on the earth, setting captives free and establishing holiness. It is our mighty weapon of war against the principalities of darkness.

Rivers are unpredictable. Twisting and turning at will, they cut a path across land that is distinct at every point. Rivers are dynamic, never static, changing constantly as the water flows. Even the same spot along a river’s edge is made new moment by moment as the water continually runs through it. Rivers have the potential to be destructive without warning when they spill over their banks and run wild. In the same way, the life and deeds of God are new every morning, and in prayer we must seek God for his direction to stay on course. Prayer has proven time and time again to be a holy rebellion to the status quo. Bold new ideas come into play when we pray.

Rivers are manageable. They have great power that can be harnessed to create energy as in the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River in China. The dam is the largest hydroelectric producer in the world. It produces 22,000 megawatts of electricity, enough to run over 4 million homes. Rivers can be very productive if the right strategy is applied and implemented. They are one of nature’s finest resources. The river of prayer has been manageable over the centuries. Implementing proven methods and organizing resources yields maximum fruitfulness because it promotes longevity in personal and corporate prayer.

Learning from Jesus. The headwaters of Christian prayer begin with Jesus. He set the example and practice for us by the prayer in his own life. He would go off to lonely places and pray. Sometimes he would draw apart to a mountain and spend the night praying alone. He prayed in public and he prayed with his disciples in John 17. He taught the importance of praying, “Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; the one who seeks finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened. Which of you, if your son asks for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a snake? If you, then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good gifts to those who ask him!” (Matthew 7:7-11).

Tommy Tyson, a famous Methodist evangelist (1922-2002), summed up the Master’s prayer life by observing: (1) Jesus prayed to know God, (2) he prayed to know God’s will, (3) he prayed to receive power to do the will of God, and (4) he prayed to persevere in doing God’s will.

“Very early in the morning, while it was still dark, Jesus got up, left the house and went off to a solitary place, where he prayed” (Mark 1:35). I call this form of prayer seeking God’s face, not just his hand. Scripture admonishes us to do this, “My heart says of you, ‘Seek his face!’ Your face, Lord, I will seek” (Psalm 27:8).

Most praying is asking God for something. In seeking his face, we pray with an open heart to know him more intimately. We want to know his ways and not just his acts (Psalm 103:7). We seek his face to know his identity, his beauty, his holiness, his good pleasure, his perspective, and his voice in all matters. We want his favor on our children, home, church, and nation. Plus, the essence of this kind of praying is a process whereby we are being conformed into the image of God. The ultimate purpose of prayer is to become like Jesus (Romans 8:29).

Jesus prayed to receive the power of the Holy Spirit to accomplish the will of God. We read in Luke 3:21-22, “When all the people were being baptized, Jesus was baptized too. And as he was praying, heaven was opened, and the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: ‘You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.’” Note the phrase, as he was praying the Spirit descended on him. Again, on the Mount of Transfiguration it says that “as he was praying, the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning” (Luke 9:29). In Luke 5:16, “But Jesus often withdrew to lonely places and prayed … and the power of the Lord was present for him to heal the sick.” Prayer is a welcome mat to the Holy Spirit. Often, we can know the will of God but without power to accomplish it we come up short.

Sometimes rivers – like the Niagara, which is only 36 miles long – have a great waterfall. So as with this river called prayer, we pray, and the Spirit brings a waterfall of grace over a city or an area. History bears witness to this in Acts 2, and the outpouring of the Spirit on the Day of Pentecost. Other revivals in history bear witness to this spiritual phenomenon because they happened after prolonged periods of prayer.

We pray to persevere. In this world there is resistance to the kingdom of light. Prayer is our weapon in spiritual conflict. Jesus modeled this for us and taught us to pray and prevail. In the Garden of Gethsemane he travailed in prayer facing the cross. As he prayed angels came and strengthened him (Luke 22:43). Then he told us, “Be always on the watch, and pray that you may be able to escape all that is about to happen, and that you may be able to stand before the Son of Man” (Luke 21:36).

In John 17, Jesus prayed for a number of important things: that the Son would glorify the Father, that his disciples would be protected by his Name, that we might have the full measure of joy, that we be protected from the evil one, that we would be sanctified in truth. He prayed for them and those who were to believe in him, that we would be brought to complete unity in order that we may be one, that we would be like him now and forever, that the Father’s love for Jesus might be in us.

The Amazon River is the largest river in the world. It stretches 4,200 miles across a basin the size of five states of Texas. On any given day it has a volume of 20 percent of the world’s fresh water supply. And when it empties into the ocean it dilutes the salt water for 100 miles. The sustenance and volume of the river of prayer over the past 21 centuries has been in the name of Jesus. This is the unique and distinctive factor of the Christian tradition. It is the one common utterance that we have that other religions do not have. It sets our praying apart in so many ways. From St. Augustine to Martin Luther to John Wesley and Bill Bright this has been the common thread their praying.

Jesus said, “And I will do whatever you ask in my name, so that the Father may be glorified in the Son. You may ask me for anything in my name, and I will do it” (John 14:13-14) Praying in Jesus’ name is based on his righteousness. We pray according to his track record and not our own.

God’s reputation is at stake by the way his followers pray and live. We are his hands and feet in the world. We are his ambassadors. We represent God to a watching world.

Terry Teykl is a United Methodist clergyperson who has devoted his life and ministry to prayer. He is also the author of numerous books, including Pray the Price, Blueprint for the House of Prayer, and Making Room to Pray. This essay is adapted from his new book Chronicles of Prayer: Praying in Jesus Name for 21 Centuries. Photo: Shutterstock.

by Steve | Sep 7, 2022 | Sept-Oct 2022

By Jenifer Jones

The northern European country of Estonia is bordered to the west by the Baltic Sea, and to the east by Russia. In the last several months, thousands of Ukrainians have either passed through on their way to other places in Europe, or temporarily settled there as they wait for the war to end.

TMS Global international partner Hindrek Taavet Taimla (pictured here) lives in Estonia, where he pastors a church and teaches at Baltic Methodist Theological Seminary and a basic school. Both the membership and normal attendance at the church are around 20 people. But on recent Sundays there have also been 8-12 Ukrainian refugees in the pews.

“The little sanctuary is packed,” Taimla notes. “Like the Bible says, the nations have come to us, to our light, and now even that little tiny countryside congregation has the chance to do missions. And everybody senses that this is what really counts, this is what’s really important: to clothe the naked and to feed the hungry and to preach the gospel to the poor.”

The seminary and school where Taimla teach are doing their best to take in and support Ukrainian students as well. About 25 percent of people living in Estonia are ethnic Russians. Taimla notes that his seminary has always been home to both Ukrainian and Russian students. “So we have a great opportunity there to unite them,” Taimla says.

There is some friction now between Ukrainians and Russians in Estonia, Taimla notes, as more Ukrainians enter the country. He says the Church in Estonia has an important role to play in building peace. “The Church, I think, really has to take on the ministry of reconciliation, like Paul said in 2 Corinthians 5,” Taimla says.

There’s also an opportunity for the Church in Estonia to put aside personal dramas, conflicts, and politics for the sake of the gospel and help people in need. “Now that lives are on the line, it’s a matter of life and death for many people,” Taimla says. “Now it’s time to get serious. I think that has hit the church as well. Until now, we had our own opinions and differences. But for now, for this reason, we can come together. And now we do come together to seek God and pray and fast and do everything we can to host the Ukrainians.”

But Taimla wishes the Church would unite before times get hard. “People just become very devout during their hard circumstances,” Taimla says. “But I would like to see Christians become desperate for God even when circumstances aren’t bad. How do you experience revival and growth and really healthy church life in fairly good circumstances? I think that has to come from some kind of inner desperation. If the situation is not desperate, then you have to become desperate.”

While Estonian Christians host refugees, the Estonian Church is encouraged by stories of how God is caring for people in Ukraine. Taimla shares a story from Mariupol, a city that’s been devastated by weeks of shelling from Russia. A group of family and friends in Mariupol took shelter together underground. For one week, the 10 people had one package of cookies, and one 17-ounce bottle of water to share between them. “Everybody would have a little bit every day,” Taimla says. “And every day there would be new water and new cookies in the package. There was supernatural multiplication of food and they survived and then they were able to evacuate.”

The arrival of more Ukrainians is spurring the body of Christ in Estonia to lay aside division and focus on what’s truly important. Taimla says the war between Russia and Ukraine is causing Estonian Christians to pray more, seek God, and come together as they work to become ministers of reconciliation.

This story was originally written in the spring of 2022. Today, most Ukrainians have moved on because there are no jobs in the area. But a few have stayed and now run a local pub with a special Ukrainian menu. This is the sixith article in a series by TMS Global introducing voices and stories in global Methodism. Jenifer Jones is a writer who serves on staff of TMS Global; Taimla is a TMS Global international partner.