by Steve | Feb 3, 2023 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht —

In Part 1 of this series, the roots of our United Methodist conflict were examined, including what led up to the 2019 special General Conference. Part 2 covers the response to the 2019 General Conference and the events leading up to the present situation in January 2023.

Following the special General Conference, some bishops and as many as 28 out of 54 annual conferences in the U.S. declared that they would not abide by the Book of Discipline on these matters. They declared that they would operate as if the One Church Plan had passed. This has thrown the UM Church into a constitutional crisis. When a sizable portion of the church rejects the outcome of “Christian conferencing” and is unwilling to live by our duly adopted policies, there is a stalemate.

It is this constitutional crisis that has led most leaders in the church to come to believe that some form of separation is necessary (or is inevitable) to resolve the conflict. Various proposals for separation were developed and submitted to the 2020 General Conference. The election of delegates to that conference resulted in fewer traditionalist delegates being elected in the U.S., particularly among the clergy.

In an attempt to put forward an amicable separation plan, Bishop John Yambasu of Sierra Leone convened a negotiating group of prominent progressive, centrist, and traditionalist leaders, along with representatives from the Council of Bishops. Aided by the efforts of renowned mediator Kenneth Feinberg, Esq., the group came to an agreement to propose the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation. The Protocol had unanimous agreement from all the leaders in the group and was supported by nearly all the traditionalist, centrist, and progressive caucus groups in the church.

The Protocol, announced in January 2020, provided for the formation of new expressions of Methodism – new denominations that could be traditionalist or progressive in theology. Central Conferences (regions outside the U.S.) could separate from the UM Church by a two-thirds vote to join a new denomination. All its annual conferences and local churches would go with the central conference unless they chose otherwise. Annual Conferences could separate from the UM Church by a 57 percent vote to join a new denomination. All its local churches would go with the annual conference unless they chose otherwise. Local churches could separate from the UM Church by either a simple majority or two-thirds vote (as chosen by their church council). This process provided a uniform way for separation to occur, with the hope of minimizing conflict at the local church level. Only those local churches that disagreed with their annual conference’s decision would have to vote.

Financially, no annual conference or local church would have had to make payments to depart from the UM Church, other than the request to be current on apportionments at the time of departure. Pension liabilities would be transferred to the new denomination for those who separated. New traditionalist denomination(s) would receive $25 million from the UM Church over four years and new progressive denomination(s) would receive $2 million. (It was anticipated that any progressive denomination forming would be much smaller.)

This proposed amicable separation plan was broadly supported in the church and looked ready to pass at the 2020 General Conference, which would have created a uniform, orderly process for separation to occur. Then Covid hit. The 2020 General Conference was postponed until 2021, and then again until 2022. Finally, General Conference was postponed to 2024. Traditionalists staunchly opposed this final postponement. They believed it was unnecessary in the face of rapidly easing Covid restrictions. They saw it as an effort to delay separation and perhaps kill the Protocol. By this time, many centrist and progressive leaders had become disillusioned with the Protocol, believing it gave too much ground and would facilitate too much of the church separating into a new denomination(s).

Faced with this further delay and the prospect of many traditionalists beginning to vote with their feet by exiting their local UM congregations, leaders of the Global Methodist Church announced the launch of their new traditionalist denomination as of May 1, 2022. On the heels of that announcement, all the remaining centrist and progressive signatories to the Protocol withdrew their support, meaning that the Protocol would be unlikely to pass the 2024 General Conference. Separation would occur, not through an orderly and uniform amicable process, but through a chaotic, expensive provision called Paragraph 2553.

Par. 2553 was adopted by the 2019 General Conference to provide a way for the anticipated small number of churches that could not accept the decision of that Conference to adopt the Traditional Plan. However, many more churches than anticipated refused to accept the Traditional Plan, and they also refused to leave the denomination, determined to stay and resist the church’s decision.

Three years later in 2022, Par. 2553 became the only exit route available for traditionalist churches that had had enough of the denominational chaos and disobedience and wanted to join a new traditionalist denomination that aligned with their historic theological perspective. Attempts were made by annual conferences to vote to withdraw from the UM Church, based on an earlier Judicial Council ruling that such withdrawals were constitutional. The Bulgaria-Romania Conference withdrew successfully under these provisions. However, the Judicial Council then clarified (at the bishops’ request) that, while annual conference withdrawal was constitutional, the General Conference must adopt a process for that to happen, which now could not be adopted until at least 2024. The door for annual conferences to depart under the Discipline was closed.

There were discussions between traditionalist leaders and a team from the Council of Bishops about creating a separation pathway for local churches using a different paragraph of the Discipline. The goal was to keep as much of the Protocol process as possible but use a different provision already in the Discipline to do so. In the end, not enough bishops wanted to develop a Protocol-like process and the discussions collapsed. The Judicial Council then ruled (at the bishops’ request) that this different paragraph (2548.2) could not be used for separation.

The church was left with only Par. 2553 as an avenue for separation to take place, and that avenue would expire on December 31, 2023. Unfortunately, the cost of pension liabilities was much higher in 2021 than was anticipated in 2019. (Those costs have since come down substantially, which is helpful.) In addition, Par. 2553 allows annual conferences to impose added costs and requirements for local churches to separate. About one-third of U.S. annual conferences have imposed costs that made separation difficult or even impossible. Some conferences require up to 50 percent of the property value be paid to the conference. Other conferences added substantial insurance or personnel costs. Two U.S. annual conferences prohibited any local churches from departing because they said their conferences were following the Discipline and churches had no grounds for separation. (One of those conferences has since provided an alternative method of separation that may work but has not yet been tested.)

A few conservative annual conferences created a gracious exit pathway for congregations by using annual conference reserve funds designated for pensions to offset the required pension liabilities. This allowed local churches to avoid burdensome financial payments and recognized that all the conference’s churches had contributed to those reserve funds and should benefit equally from them.

Unfortunately, some annual conferences took a more adversarial stance and did everything they could to prevent local churches from disaffiliating. Some imposed rigid deadlines and detailed procedures. Some forbade the sharing of information with churches by persons interested in disaffiliating. Complaints have been filed against some traditionalist clergy for sharing information. Accusations of misinformation and deception have flown back and forth between both sides of the debate. One annual conference initially agreed to offset pension liabilities with reserve funds, but later rescinded the offer, tripling a local church’s cost of disaffiliation. The North Georgia Conference at the end of 2022 prohibited all disaffiliations because of allegations of “misinformation,” disrespecting the ability of lay members to sort through the information presented by both sides and make their own choices.

None of this adversarial behavior needed to happen. It could have been avoided with the adoption of the Protocol or something like it. Some bishops and other denominational leaders chose to maximize “command and control” in an effort to coerce as many churches into remaining United Methodist as possible. While they may succeed in retaining more churches in the short term, they have created an even more unhealthy denominational environment in the long run. This unhealthy environment will undoubtedly impact the ability of the UM Church to thrive and grow in the future (which it has not since its formation in 1968).

Despite the challenges, at the end of 2022 more than 2,000 congregations had officially disaffiliated from the UM Church and 1,100 of them had officially joined the Global Methodist Church. More churches are still in the pipeline to join the GM Church. It is estimated that an additional 1,000 to 3,000 churches may disaffiliate from the UM Church in 2023 before Par. 2553 expires. A few annual conferences are having special meetings toward the end of the year to approve last-minute disaffiliations.

As this account is written in early 2023, changes and developments are happening at a rapid pace. Further Judicial Council decisions are anticipated that may strengthen the denominational hierarchy’s hand. A new exit path is needed to replace the expiring Par. 2553 for local churches that chose to wait for General Conference 2024 or who were locked out of the disaffiliation process for one reason or another. The Council of Bishops now claims that Par. 2553 does not apply outside the U.S. A clearer exit path for annual conferences and local churches outside the U.S. is needed. The need to stay engaged in the conflict through General Conference 2024 and its aftermath ensures that high-stakes confrontations will continue. We continue to pray that God opens a window where every door has been shut.

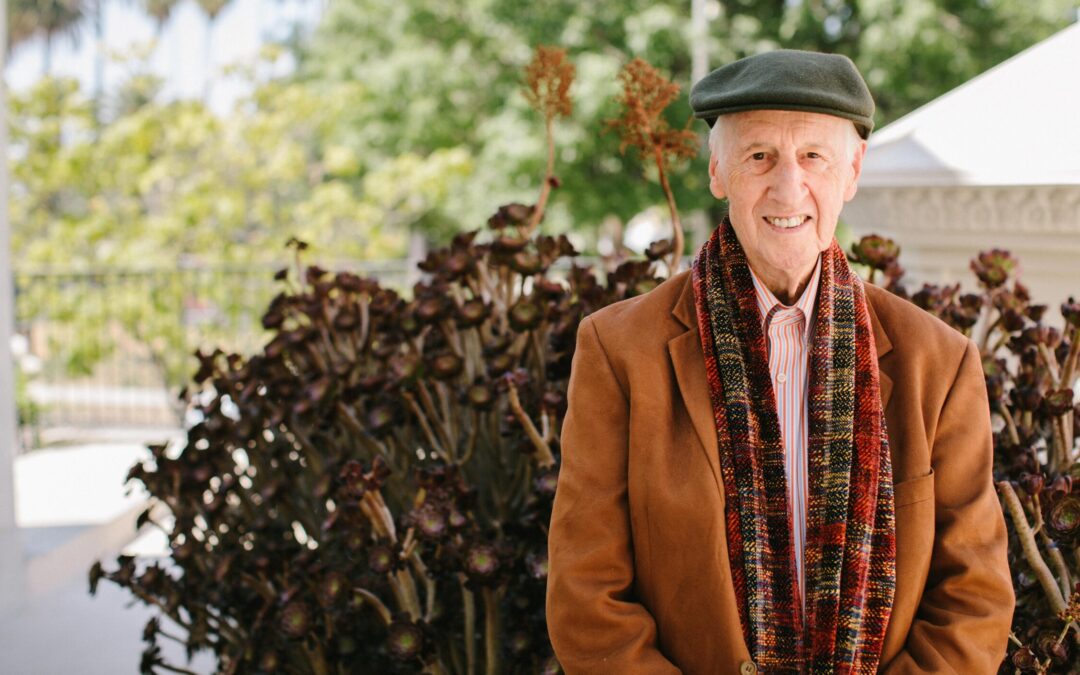

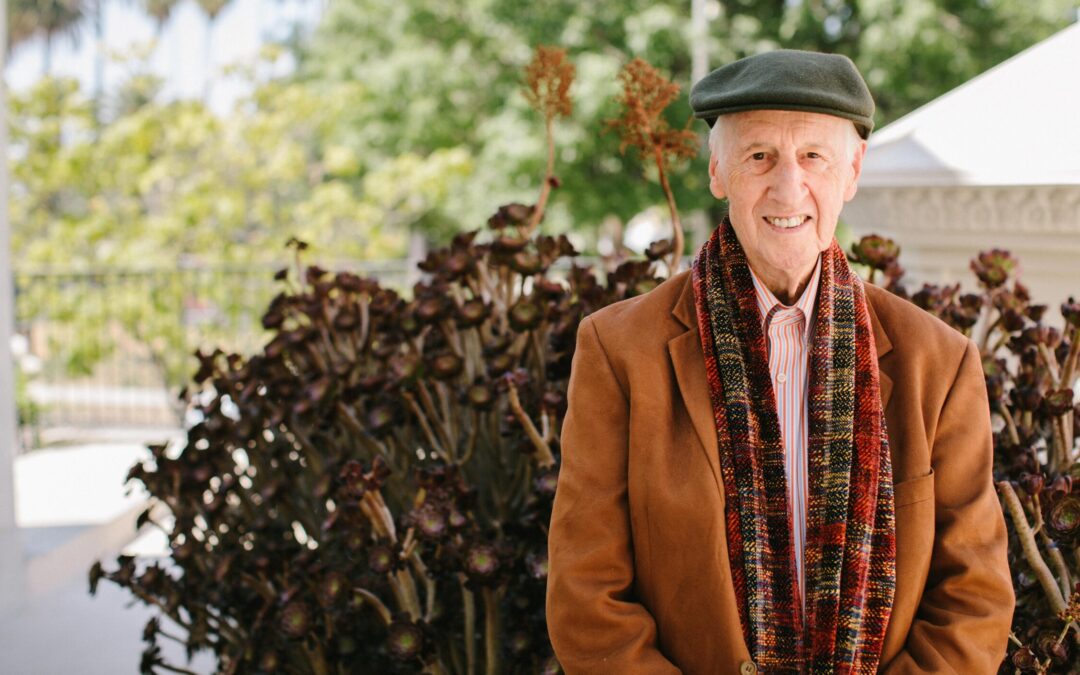

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and vice president of Good News.

by Steve | Jan 27, 2023 | In the News

By Thomas Lambrecht —

The current state of separation and disaffiliation in The United Methodist Church has roots stretching far back into Methodism’s history. Profound disagreements about theology, spirituality, and hot-button social issues have been brewing within Methodism for decades.

“Creeds have had their day. They are no longer effective,” said one liberal writer in Methodist Review clear back in 1910. “Without doubt, they were well intended. Possibly they have done some good – they certainly have done much harm…. The revolt against creeds began in the lifetime of many now active in the work. The creeds are retired to the museums and labeled ‘Obsolete.’”

In his book The Rise of Theological Liberalism and the Decline of American Methodism (Seedbed), the Rev. Dr. James V. Heidinger II writes that “the seeds for Methodism’s decline were sown more than a hundred years ago – in the period of the early 1900s. This was an era in which theological liberalism brought sweeping change to the substance of Methodist thought and teaching. While not embraced widely by local church pastors and most laity, it was affirmed by much of Methodism’s leadership during that period – including many bishops, theologians, editors of publications, board and agency staff, and pastors of large urban churches” (page 190).

Heidinger – our president emeritus at Good News – notes this was an era “in which Methodism and the other mainline denominations experienced major doctrinal transition and revision. For a number of Methodist pastors and leaders (and most all of the mainline Protestant churches in America, for that matter), there was a move away from the supernatural elements of the faith. Doctrines such as the virgin birth, the resurrection of Christ, the miracles, the ascension, and the promised return of Christ were difficult to affirm amid the exhilarating and supposedly liberating views of the new science and emerging rationalism” (Ibid, p. 190).

Sadly, similar to today’s situation, “Methodist bishops were concerned that renewed doctrinal controversy might lead to further division across Methodism,” notes Heidinger. “They were determined to avoid controversy at all costs and thus chose to emphasize unity and collegiality rather than engage the serious doctrinal questions that were challenging and changing the historic doctrines of their church” (Ibid, p. 191-192).

1972 General Conference

Out of the soil of this unresolved doctrinal confusion, one of the manifestations or “presenting issues” of our fractured church emerged in 1972, when the General Conference endorsed “theological pluralism” and the Board of Church and Society proposed the very first Social Principles for the new United Methodist Church (founded in 1968). One of the provisions in the proposal indicated a sympathetic acceptance of homosexuality. Traditionalist delegates at General Conference were concerned that the biblical position regarding same-sex behavior was disregarded, and the conference voted to add words clarifying that “the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.” Those words have remained in our Social Principles ever since.

Almost immediately, those who disagreed with a traditionalist position began lobbying to remove those words and change the church’s position to one of tolerance and even affirmation of same-sex practices. The church was not able to deal effectively with instances of high-profile disobedience through the normal accountability channels. This led to the addition of language in subsequent General Conferences mandating “fidelity in marriage and celibacy in singleness” for clergy, prohibiting the candidacy, ordination, or appointment of “self-avowed practicing homosexuals” as pastors, or performing of same-sex weddings. Each time language was added, it was to close a loophole in the accountability process to reflect the church’s historic teaching.

Over the past 50 years, there have been several church-wide studies, many annual conference task forces, and numerous dialogs between persons with opposing perspectives, seeking to come to some common ground. Often, these experiences were heavily weighted toward a liberal understanding of affirmation and were seen by traditionalists as a way to try to manipulate the church into changing its position. Regardless, the outcome at every General Conference has been to affirm the historic and biblical teaching of the church.

No Theological Accountability

The theological conflict broadened in scope when Bishop Joseph Sprague, serving Northern Illinois at the time, published a book entitled Affirmations of a Dissenter in 2002. As my colleague, the Rev. Scott Field, describes Sprague’s views, he “denied Christ’s virgin birth, bodily resurrection, and atoning death, asserting that Jesus was not born divine but became divine through the faithfulness of his earthly walk, with the implication that others could follow suit.” Sprague suggested an alternative Trinity of Jesus, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Field asked Sprague subsequently about the role of orthodox affirmations of faith such as the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed. According to Field, “He told me that the historic Christian creeds were simply a matter of who showed up with the most votes when the church councils got together. We are free, he said, to change ‘orthodoxy’ whenever we have majority votes to do so.”

I was part of a group of 28 clergy and laity who filed a complaint against Bishop Sprague for the chargeable offense of “dissemination of doctrines contrary to the established standards of doctrine of The United Methodist Church.” While those of us who filed the complaint were criticized for doing so, there was no rebuke of Sprague’s doctrinal deviation, and the complaint was dismissed. This episode demonstrated that even blatant departure from the church’s teachings would be tolerated and even affirmed by the church’s hierarchy. (One active bishop wrote a glowing endorsement of Sprague’s book.) There was an unbridgeable divide between those holding to traditional Methodist doctrine and those open to varieties of belief and even changes in doctrine.

2012 General Conference

The closest the church came to changing its position regarding marriage and sexuality was in 2012, when a motion to say that the church is “not of one mind” on these concerns failed 54 to 46 percent. In the run-up to that General Conference, over 1,100 clergy signed up on a website their willingness to perform same-sex weddings in defiance of the Book of Discipline. In 2013, retired Bishop Melvin Talbert performed a same-sex wedding in Alabama despite the request of Northern Alabama Bishop Debra Wallace Padgett that he not do so. A complaint was filed against Talbert. It was eventually dismissed.

Talbert’s action was joined by a number of other situations around the U.S. when ordained clergy performed same-sex weddings. In each instance, when complaints were filed against such clergy, the “penalty” was a 24-hour suspension or some other nominal consequence. In some cases, clergy were required to explain in writing to their colleagues why they violated the Discipline, giving those clergy an official platform to promote their views contrary to church teaching. The clergy accountability system was failing to require clergy to conform their actions to what the General Conference had decided on behalf of the whole church.

On the Verge of Schism

Just before the 2016 General Conference, Bishop Talbert performed another same-sex wedding in North Carolina. Again, there were no consequences or accountability. At the 2016 General Conference, efforts to reinforce the long-standing position of the church were being passed in committee by a greater margin than before, and there was talk that the church might split over this conflict.

I was present in private conversations where a group of prominent traditionalist, centrist, and progressive leaders agreed that a separation of the church was inevitable. The group saw the best way forward to be providing as amicable and mutually respectful a process of separation as possible, as a witness to a watching world. The group sent a request to the Council of Bishops meeting during General Conference to form a commission to develop an amicable process of separation.

The Council declined to accept the possibility of separation. Instead, they proposed forming a Commission on a Way Forward (COWF) to find a way to resolve the conflict, while preserving as much unity in the denomination as possible. The 2016 General Conference agreed, and all proposals regarding sexuality were put on hold until a special 2019 General Conference that would deal only with this issue. The Commission (of which I was a member) came up with three proposals: a Traditional Plan to strengthen accountability to the church’s current position, a One Church Plan to allow annual conferences and local churches to determine their own stance on same-sex marriage and ordination, and a Connectional Conference Plan to create three new “jurisdictions” within the UM Church, based on viewpoint on ministry with LGBTQ persons.

The Traditional Plan was an 11th hour proposal developed by only a few members of the Commission, as the Council of Bishops had previously prevented consideration of either separation or maintaining the status quo by the Commission. We understand that some African bishops objected that there had to be a Traditional Plan on the table for the General Conference to consider, which prompted the Council to reverse course and permit such a plan. The Traditional Plan did not have the benefit of a thorough refinement by the full Commission and was proposed at the Commission’s last meeting only a few months before the deadline for submitting legislation to General Conference. (Indeed, some Commission members said they could not in good conscience work on a Traditional Plan, even though traditionalists had been willing to work on other plans we disagreed with.)

A special General Conference was held in St. Louis in February 2019 to address the COWF proposals. The Traditional Plan passed by 53 to 47 percent. However, about half the provisions of the Traditional Plan were declared unconstitutional by the Judicial Council, due to the lack of adequate refinement of the plan by the Commission. More problematic than the actual voting were the vitriolic rhetoric and personal attacks in speeches from the floor, particularly by some centrist and progressive delegates.

Part 2 of this series will deal with the aftermath of the special General Conference and the developments that lead to our current impasse.

Thomas Lambrecht is a United Methodist clergyperson and the vice president of Good News. Photo: A delegate speaks during a plenary session of the historic 1968 Uniting Conference of The United Methodist Church. A UMNS photo courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History.

by Steve | Jan 20, 2023 | In the News

By Keith Boyette —

The process of church disaffiliation has completed its second wave, with churches disaffiliating through special sessions of their annual conferences in the fall. This piecemeal process of disaffiliation is not what we had hoped for when I joined other traditionalist, centrist, and progressive leaders to announce the Protocol for Reconciliation and Grace through Separation agreement three years ago. If General Conference had met in 2020 or even in 2022, there would have been a uniform process for disaffiliation that would have allowed annual conferences and local churches to make an informed, prayerful, conscience-driven decision on where their congregation could best serve the Kingdom of God.

Unfortunately, we have a dysfunctional situation that is causing increased conflict and power plays to block disaffiliation in some places. Despite the challenges, over 2,000 churches have already disaffiliated from The United Methodist Church (UM Church) and many more are in the process to do so during this year.

Now that two waves of disaffiliation have been completed, people wonder what progress the Global Methodist Church is making in its formation.

The GM Church began operations on May 1, 2022. In its brief life, it has welcomed more than 1,200 persons as clergy members and officially welcomed 1,100 local churches that applied to align with it. The GM Church is already larger than the Congregational Methodist and Free Methodist Churches and should soon pass the Wesleyan Church in size. These clergy and churches are from Angola, Bulgaria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, England, Panama, the Philippines, Slovakia, and the United States.

And hundreds of additional clergy and local churches are on the cusp of completing the process of disaffiliation from The United Methodist Church in order to align with the GM Church. Also, more than 50 new GM congregations have been launched globally with more being added each month. And the truth is, many more would have already joined the GM Church, or be well on the way to doing so, were it not for the obstacles UM Church bishops and conferences have placed in their way.

The GM Church’s primary focus is on its mission – to make disciples of Jesus Christ who worship passionately, love extravagantly, and witness boldly. It is a Church that intentionally empowers local congregations to have maximum discretion in the way they organize and deploy resources for ministry. The denomination maintains a small institutional footprint to ensure local churches have the resources to support the ministry to which they are called. The GM Church exists to empower local churches; to serve, not to be served.

Considerable time has been devoted to organizing for ministry in the various regions of the world. The GM Church currently has nine provisional annual conferences and districts around the world. These conferences and districts have presidents pro tempore and presiding elders appointed to serve. Some have already held convening conferences. Others are holding such conferences soon. It also has ten transitional conference advisory teams preparing for the launch of additional provisional conferences and districts in the coming months with more being organized monthly.

The process of organizing the church internationally involves registering the GM Church with the government of each country. It has completed this process in Bulgaria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Philippines, and Slovakia. Registration is underway in a number of other countries around the world. Ultimately, the GM Church will be registered in nearly all of the countries of Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. The denomination is also in discussions with non-UM clergy and churches around the world, many of whom are steeped in Methodist heritage and traditions. For them, the GM Church offers an opportunity to join a new, vibrant movement grounded in the warm hearted Wesleyan expression of the Christian faith.

Navigating such a dynamic environment requires exceptional sensitivity to, and dependence on, the work of the Holy Spirit. The GM Church’s Transitional Leadership Council (TLC) is diverse, globally representative, and composed of exceptional leaders. Recently, Bishops Mark Webb and Scott Jones have joined the TLC, along with new members Rev. Arturo Cadar (Eastern Texas, Deacon), Rev. Dr. David Watson (Allegheny West, Elder), and Rev. Bazel Yoila Yayuba (Nigeria, Elder). The TLC will continue to guide the GM Church through its critical transitional period, even as it joyfully looks forward to the new denomination’s convening General Conference.

Of course, starting a new denomination requires significant financial resources. Thanks to hundreds of gifts from faithful Methodists from all around the world, at its inception, the GM Church received over $1 million as a substantial seed money grant from the Wesleyan Covenant Association’s Next Methodism Fund, which had been specifically raised for that purpose. In addition to this gift, individuals, local churches, and other entities have continued to generously support the Church in its transitional season. Through December 31, 2022, it has received $210,000 in direct contributions, enabling it to fulfill its calling in its early days.

And as local churches join the denomination, they are now

supporting the ministries of their provisional annual conferences and the general church through connectional funding. The TLC, when requested, has granted relief from connectional funding for congregations that have incurred substantial financial burdens as part of withdrawing from the UM Church.

The GM Church is also equipping and encouraging congregations to fulfill its calling to be a global missional partner with Christian movements around the world. It is a platinum sponsor of the Beyond These Walls conference that will be held at The Woodlands (TX) Methodist Church from April 27-29, 2023. It will gather Christian leaders from around the world, many of whom will be GMC clergy and laity, and will challenge us to share the good news of Jesus Christ with all people.

In this space, I can only focus on a few highlights, but all the people of the GM Church celebrate the way in which God is at work in our midst. We have much for which we give thanks. We have only just begun. We will keep our focus primarily upon our mission – to make disciples of Jesus Christ who worship passionately, love extravagantly, and witness boldly. God expects great things from us. By God’s Spirit, we strive to accomplish great things for God, all so that Jesus will be glorified.

The Rev. Keith Boyette is the Transitional Connectional Officer of the Global Methodist Church, its chief executive and administrative officer. A version of this article appeared earlier this week in the GM Church Outlook.

The GM Church has a website with a wealth of information. The Church encourages you to visit it to learn about its mission, purpose, core confessions, organization, and find answers to a variety of questions.

by Steve | Jan 17, 2023 | In the News

By Steve Beard —

Over the last 40 years, one of the most popular and memorable modern day hymns is “Majesty, Worship His Majesty” written by Jack Hayford. Congregations from all denominations around the globe have sung it with reverence and gusto. It is included in The United Methodist Hymnal, as well as the new collection titled Our Great Redeemer’s Praise.

On Sunday, January 8, 2023, Hayford died at the age of 88 years old. He was a beloved clergyman, prolific songwriter, and sought-after mentor. “Today, we mourn his loss but celebrate the homecoming of a great leader in God’s kingdom,” announced Hayford’s ministry. “We know that this great servant and worshipper is now experiencing the greatest worship service of all.”

For thirty years, Hayford was the pastor of The Church on the Way in Southern California. To an entire generation of church leaders, he was an irreplaceable bridge-builder between Pentecostal/charismatic believers and the wider ecumenical Church.

Fittingly, Hayford’s international notoriety sprung from his memorable worship song. “Majesty” was written in 1977 while he and his family were vacationing through England during the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth. As they roamed through historic Blenheim Palace, the birthplace and ancestral home of Winston Churchill, Hayford was inspired by the regal surroundings.

Thinking from the heart, he became mindful “that the provisions of Christ for the believer not only included the forgiveness for sin, but provided a restoration to a royal relationship with God as sons and daughters born into the family through His Majesty, Our Savior Jesus Christ.”

As he was driving around England, Jack asked his beloved wife Anna to write down the words and melody. “So exalt, lift up on high, the name of Jesus/ Magnify, come glorify Christ Jesus, the King.”

Hayford reports that he was filled with a powerful “sense of Christ Jesus’ royalty, dignity, and majesty …. I seemed to feel something new of what it meant to be his! The accomplished triumph of his Cross has not only unlocked us from the chains of our own bondage and restored us to fellowship with the Father, but he has also unfolded to us a life of authority over sin and hell and raised us to partnership with him in his Throne – Now!”

This is one of the many glimpses into the man found in Pastor Jack, the 2020 biography written by Dr. S. David Moore about Hayford’s noteworthy ministry as pastor, Bible teacher, author of 50 books, writer of more than 500 worship songs, editor of the Spirit-Filled Life Bible, denominational leader of The Foursquare Church, and founder and chancellor emeritus of The King’s University (now located in the Dallas area).

“Jack lived in a God-charged, open universe that challenged the reductionism of the modern world,” observed Moore. “At a time in which reality came to be defined in purely naturalistic terms, dismissing the supernatural as antiquated folklore, Jack Hayford’s life and ministry offered a recovery of the biblical world, a world in which God is active and present in his creation.” His teaching and leadership often made memorable impressions on non-Pentecostal believers.

“I’ll never forget the wonderful way Jack Hayford led us in a concert of prayer at the Promise Keeper’s Million Man March in Washington, D.C., in 1997,” recalled Dr. Stephen Seamands, professor emeritus of Christian Doctrine at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. “He was such a Christian statesman and role model for me. In his book, A Passion for Fullness, he writes, ‘Let us commit ourselves wholeheartedly to a supernatural ministry disciplined by a crucified life.’ That summed up what I was striving for so well for me.”

In addition to his teaching on the work of the Holy Spirit, Hayford’s thoughts on worship are an essential factor in comprehending his ministry. “In both the Old and New Testaments,” he taught, “God’s revealed will in calling his people together was that they might experience his presence and power – not a spectacle or sensation, but in a discovery of his will through encounter and impact.”

Hayford taught extensively about heartfelt worship being far more dynamic than what is sometimes mistaken as merely the order of a service in a church bulletin. “In my experience, theological discussions about worship tend to focus on the cerebral, not the visceral – on the mind, not the heart. ‘True’ worship,” he wrote, “we are often taught, is more about the mind thinking right about God (using theologically correct language and liturgy), rather than the heart’s hunger for him.

“But the words of our Savior resound the undeniable call to worship that transcends the intellect: ‘God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth’ (John 4:24). We’ve been inclined to conclude that mind is the proper synonym for spirit here, but the Bible shows that heart is a better candidate. ‘In truth’ certainly suggests participation of the intellect in worship, but it is inescapably second – and dependent upon the heart’s fullest release first.”

Hayford concluded, “The exercises of our enlightened minds may deduce God, but only our ignited hearts can delight him – and in turn experience his desire to delight us.”

As a church leader, Hayford was faithfully committed to biblical exposition, racial reconciliation, teaching on the Kingdom of God, praying for churches and leaders outside his own Pentecostal tradition, discerning the difference between “holy humanness and human holiness,” explaining the “beauty of spiritual language” (speaking in tongues), and maintaining irrevocable honesty in his heart.

“My commitment to walk with integrity of heart calls me to refuse to allow the most minor deviations from honesty with myself, with the facts, and most of all, with the Holy Spirit’s corrections,” Hayford believed.

Hayford saw “his private prayer life as the essential foundation of his ministry, and he deeply yearns to know and please God and live in radical dependence,” wrote Moore in Pastor Jack. “His journals are filled with prayers of confession, praise, and especially lament for his weaknesses and shortcomings. And yet almost always his journal entries end with grateful affirmation of God’s faithfulness to his promises.”

The Church on the Way was located only a few miles from the glamour of Hollywood and it attracted a handful of high-profile members of the entertainment industry. However, the congregation grew steadily without glitz or publicity stunts. Hayford’s appeal was built on his personal humility, integrity, and honesty.

“There is, in whatever one studies of Jesus, everything of humanity and nothing of superficiality; everything of godliness and nothing of religiosity,” wrote Hayford. “Jesus ministered the joy, life, health and glory of his Kingdom in the most practical, tasteful ways. There is nothing of the flawed habit of hollow holiness or pasted-on piety that characterizes much of the Christianity the world encounters.”

Authentic discipleship – to be “Spirit-formed” as Hayford called it – involves nurturing intimacy with God. In his relationship with Jesus, Hayford was committed “to seek him daily (1) to lead and direct my path, (2) to teach and correct my thoughts and words, (3) to keep and protect my soul, and (4) to shape and perfect my life.”

Hayford’s love and concern for clergy of all traditions earned him the title of “pastor to pastors.” Despite coming from a relatively small classical Pentecostal denomination, his generous spirit had wide appeal.

“I have a shepherd’s heart,” Hayford said prior to his death. Whether he was teaching before 39,000 clergy in a football stadium or hosting a dozen pastors in his living room, Hayford etched a lasting impression on those that he treasured so much. In a previous era of polarization and mistrust, Hayford stood out as a passionate worshipper and peacemaker. He left a robust legacy of vulnerability and devotion through living a life that was animated by the presence and love of God.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.

by Steve | Jan 14, 2023 | In the News

The prolific Methodist evangelist E. Stanley Jones (1884-1973) was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1963. As a missionary in India, he became a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi. Jones even wrote a biography of Gandhi – one that inspired Martin Luther King, Jr. and his message of “non-violence” during the Civil Rights Movement. Time Magazine called Jones “the world’s greatest Christian missionary.”

Before graduating in 1906 from Asbury College in Wilmore, Kentucky, Jones experienced a remarkable event.

“Four or five of us students were in the room of another student, Jim Ballinger, having a prayer meeting about ten o’clock at night,” recalled Jones in his autobiography A Song of Ascents. “I remember I was almost asleep with my head against the bedclothes where I was kneeling, when we were all swept off our feet by a visitation of the Holy Spirit. We were all filled, flooded by the Spirit. Everything that happened to the disciples on the original Pentecost happened to us.”

Jones admits that he was “tempted to tone down what really happened, or to dress it up in garments of respectability by using noncommittal descriptive terms. In either case it would be dishonest and perhaps worse – a betrayal of one of the most sacred and formative gifts of my life, a gift of God. To some who have looked upon me as an ‘intellectual’ it will come as a shock. But shock or no shock, here goes.”

Being willing to be misunderstood, Jones wrote, “For three or four days it could be said of us as was said of those at the original Pentecost. ‘They are drunk.’ I was drunk with God. I say ‘for three or four days,’ for time seemed to have lost its significance” (page 68).

[“The first night I could only walk the floor and praise him. About two o’clock L. L. Pickett, the father of Bishop J. Waskom Pickett, came upstairs and said: ‘Stanley, he giveth his beloved sleep.’ But sleep was out of the question. By morning the effects of this sudden and unexpected ‘outpouring’ had begun to go through the college and town. That morning there was no chapel service, in the ordinary sense; people were in prayer, some prostrate in prayer. No one led it, and yet it was led – led by the Spirit. For three days there were no college classes. Every class room was a prayer meeting where students and faculty were seeking and finding and witnessing. It spread to the countryside. People flocked in, and, before they could even get into the assembly hall, would be stricken with conviction and would fall on their knees on the campus crying for God – and pardon and release. I was praying with seekers on the inside of the hall when some- one came to me and said: ‘Come outside. There are people kneeling on the campus who need your help.’

[“And then a strange thing happened: I was taken possession of by an infinite quiet. I found myself tiptoeing as I walked through that auditorium of seeking and rejoicing people. I found myself talking in whispers, the outer expression of this holy calm within. And yet it was a dynamic calm, something akin to the calm at the center of a cyclone – the calm where the dynamic forces of the cyclone reside. It was easy to help people through to victory and release. From then on till this movement of the Spirit subsided there was nothing but a holy calm within me.”] …

What was the fruit of the experience? “I was released from the fear of emotion. I had tasted three days of ecstasy – drunk with God,” testified Jones. “And yet they were the clearest-headed, soberest moments I have ever known. I saw into the heart of reality, and the heart of reality was joy, joy, joy. And the heart of reality was love, love, love.” (page 69).

(Adapted from “The Unpredictability of Encountering a Holy God” by Steve Beard in Power, Holiness, and Evangelism, [1999 Destiny Image Publishers] compiled by Randy Clark.)